9Orality and Literacy of Online Communication

Abstract: The ongoing advancement of the technical possibilities makes electronic media increasingly multifunctional. Online communication is therefore no longer a simple transmission of a message from the sender to the receiver, but a new form of interaction with many participants who create and discuss meaning. This leads to new perspectives in different fields of scientific research and requires an interdisciplinary access. Also the distinction and functionalization of orality and literacy has to be revisited, because a major part of online communication is written, although the features of orality cannot be ignored. What is more, the advancing appearance of hybrid communication forms integrating sound and pictures in traditionally written contexts complicates clear allocations. Research will have to rethink the existing models and create a new access that overcomes the old dichotomious structures. The article analytically reviews the leading theories and models on this subject and reflects the current debate, taking into consideration as well terminological as methodological questions.

Keywords: immediacy-distance continuum, linguistic change, media convergence, online communication, orality and literacy, variation in online communication

1Linguistic research framework

1.1Important questions

In times of ongoing technical evolution, the distinction and functionalization of orality and literacy in human communication becomes increasingly complicated. What seemed to be quite clear following the Koch/Oesterreicher model in differentiating oral and literal utterances and texts of non-digital communication (cf. Koch/Oesterreicher 1985; 2001; 2007a; 2007b; 2008; 22011; 2012), is getting ever more complex and blurred in online communication. Although the medial dichotomy between written (graphic) and spoken (phonic) code still exists in the “New” Media, there is a growing awareness of the difficulty to separate the two levels. Graphically represented messages in online communication often show features characteristic for speech and interactive discourse, but at the same time they differ a lot, stylistically from face-to-face conversation. What is more, the advancing appearance of hybrid communication forms integrating sound and pictures in traditionally written contexts complicates clear allocations. As online communication is furthermore difficult to locate on the immediacy-distance continuum, the analysis of the numerous language varieties in online communication has become an important task in current linguistics.

However diverse the various forms of online communication, they are similar in several points: They are

–primarily graphically realized (even if this is currently changing)

–mediated by networked computers, tablets, cell or smartphones

–based on technical devices on both sides of the communicative act (“Tertiärmedien”)

–mainly independent of time and place

–suitable for subsequent modifications and replies

–technically documentable.

The first research results in the linguistic analysis of online communication were mainly based on communication forms like e-mail, chat and text messaging and therefore optimistic about the possibility of new, clear and simple models (more on this below in chapter 2.1). For instance, an e-mail is a relatively clearly-defined communication form which has a specific, technically-dictated appearance. It can contain different content and text forms (e. g., an appointment for lunch as well as a letter of application or a report on research results) and so its linguistic conception can differ a lot, but formally and medially it underlies restricted criteria. The same applies to chat and text messaging. The literature about these three forms is therefore abundant (more on this below in chapter 1.3; as a general overview cf. Thurlow/Poff 2013).

But in the last decade other communication channels have moved into the focus, namely the Social Networks which are harder to define from a linguistic perspective. They do not represent communication forms, nor do they consist of clearly delimitable text forms. Jucker/Dürscheid (2012, 47s.) call them “multiple-tool platforms” (e. g., Facebook, Twitter, Google+, but also Skype and online newspapers) that bundle several communication practices, in contrast to “single-tool platforms” (chat, e-mail, blog, SMS) that can be classified as being either public or non-public (e. g., blogging vs. text messaging; more on this below in chapter 2.2). These new forms – and that is not the final word – demonstrate that the continuous technical evolution implies important changes in the distinction and evaluation of orality and literacy.

The present article will analytically review the leading theories and models on this subject and reflect the ongoing discussion beyond individual media. Chapter 1 will provide information about existing definitions and research fields, while chapter 2 will focus on Romance perspectives on online communication. Chapter 3 will give a short resume and future prospects for research on this multifaceted subject.

1.2Key concepts and definitions

As communication has always been a central and well discussed phenomenon in both the popular and public discourse, the emergence of new language styles and forms that have arisen under the influence of the New Media are not always considered unambiguously positive. The main concerns attend to the perceived communicative paucity particularly of young people. These have been blamed for inventing a new “teen-talk” or “netlingo” negatively impacting standard communication and hollowing out language in the process (cf., e. g., the site <http://www.netlingo.com> or the hashtag #netlingo on Twitter) and thus produce negative impacts on the standard way of communication (cf. Thurlow 2003, or Anis 2006 who qualified the new features as “unconventional spelling” and called them “neographies”, cf. also Kallweit 2015). Most of the features criticized by academics refer to the strong influence of orality in written discourse, as there are

–abbreviations (acronyms, initialisms, phonetizations, shorthands)

–non-verbal codes (emoticons, emojis, uppercase, graphic elongations, echo characters)

–lexical reduction (in order to save time or place)

–syntactical reduction (ellipses, telegram style).

However, the often-heard concern that the loss of grammatical standards and norms in online communication could induce a certain language decay in the long run, could not be confirmed in scientific studies (cf. Brommer/Dürscheid 2009; Plester/Wood/Joshi 2009; Dürscheid/Wagner/Brommer 2010; Storrer 2010; Dürscheid/Stark 2013; Overbeck 2015). On the contrary, these studies emphasized that communication in the New Media can extend the functional area of written speech acts, because the younger generation often takes a playful and ironic approach to language use and consequently develops and improves their communication awareness rather than losing any command of the language. Users of online communication tend to adapt their writing style to addressees and contexts, even if often unconsciously. Thus, language use in online communication is strongly influenced by the medium and the context of communication as well as the situation of the participants, and in analyzing this language one should always take into consideration the users’ activities and expectations.

The question of terminology accompanies this public and scientific discussion. The difficulty of achieving a consensus definition of terms has been discussed since the beginning of scientific analysis of online communication, but not even the differentiation between the academic discipline and the matter of investigation under discussion is clearly defined: Crystal (2011) and Marx/Weidacher (2014) call it Internet linguistics/Internetlinguistik, but the term is still not standardized. Jucker/Dürscheid (2012) argue that Internet linguistics is too narrow a term (because it excludes text messaging via cell phones) while media linguistics seems too wide (because it includes research on TV, radio, newspapers etc.); they suggest the term KSC linguistics (linguistics of keyboard-to-screen communication). The public and the academic world have still not agreed on a common term.

Also, the designation of communication in the New Media varies from language to language. The most frequently used term so far is Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC), first mentioned in the 1980s (cf. Baron 1984), and still used in recent publications (cf., e. g., Herring/Stein/Virtanen 2013), but criticized meanwhile since cell phones are usually not considered computers and thus CMC excludes text messaging. To avoid exclusion of the cellular phone, other terms reflecting different concepts have been discussed, such as Electronically Mediated Communication (EMC), Digitally Mediated Communication (DMC), Internet-based Communication (IBC) or Internet-mediated Communication (IMC) (cf. Beißwenger 2007; Crystal 2011; Yus 2010; Jucker/Dürscheid 2012). Nor did the term proposed by Jucker/Dürscheid, keyboard-to-screen communication (KSC), gain wide acceptance. Cougnon/Bouraoui (↗8 Orality and Literacy of Telephony and SMS) propose the term Computer-Mediated Written Communication (CMWC) in order to distinguish the aural use of telephones from text messaging with mobile phones, which seems to be a useful differentiation, but is not suitable for new hybrid forms like mobile and voice-over-IP communication (video blogs, Internet telephony, instant messaging etc.; more on this below).

In the Romance languages we also find different terms orientated toward English expressions, such as the Italian comunicazione mediata dal computer (CMC) that is equal with the Latin-American Spanish comunicación mediada por la computadora (CMC). In Spain, comunicación mediada por ordenador (CMO) is the usual term, but in France, the corresponding communication médiée/médiatisée par ordinateur (CMO) is considered unusual and is frequently replaced by the expressions communication virtuelle or cybercommunication. The German term computervermittelte Kommunikation (CVK) is common, but also digitale Kommunikation or virtuelle Kommunikation are sometimes seen (cf. Overbeck 2014 and 2015). Therefore, all terms listed here seem to include a certain inherent vagueness that reflects the complexity of the matter itself. The present article prefers thus the wider term online communication, because it covers all sorts of electronically transmitted communication, including both mobile and computer telephony, Skype or types of voice-chat, as well as video messages on portals like YouTube. Within this broad definition, the analysis of orality and literacy becomes even more interesting as in keyboard-to-screen approaches. According to this, we follow Herring (2007, 1) in defining online communication as “predominantly text-based human-human interaction mediated by networked computers or mobile telephony”, but we will see below that the aspect “predominantly text-based” is about to change, so that the definition will have to be extended in the next decades.

1.3Research fields yesterday and nowadays

Constant technical advances create a growing multifunctionality of the electronic media and thus require a multidimensional and interdisciplinary access also in the theoretical discourse about communication. Describing how people establish and maintain interaction in online communication, and how this is technically and linguistically managed, has become a central social and scientific task. Thus are involved from the beginning of research on online communication not only the disciplines of Communications Research, Conversation Analysis and Pragmatics, but also fields like Sociolinguistics, Textual Linguistics, Corpus Analysis etc.

In the early linguistic research on online communication (1980s and early 1990s) many attempts have been made to define and to classify the language use in different communication forms (cf. the overview in Herring 2007). The first approaches were mainly sociological, focusing on aspects like social relationships and the construction of different identities (cf., e. g., Rice/Hughes/Love 1989; Rheingold 1993 and 1995; Döring 1997 and 22003 etc.). In Sociolinguistics today, the focus lies mainly on the research of youth language, the young generation being the main user group of online communication (cf. Neuland 2003; 2007; 2008; Boyer 2007; Baron 2008; Auzanneau/Juillard 2012). In Textual Linguistics, meanwhile, researchers have questioned the validity of the traditional models for the distinction of text types (based on Brinker 1993 and Brinker et al. 2000; Linke/Nussbaumer/Portmann 52004). Soon it became obvious that the appearance of New Media did not necessarily imply the requirement of new text models, but that the existing theories had to be reviewed (cf. Adamzik 2000; Eckkrammer 2001; Jakobs 2003; Rehm 2006; Fix 2011; Overbeck 2014; Marx/Weidacher 2014). In the last decade, linguistic studies of online communication have diversified and analyze language contact or code-switching among other issues (cf. Cougnon/Ledegen 2010; Cougnon 2011; Androutsopoulos 2013). Also, aspects of politeness and face work play an important role in the actual debate (based on Brown/Levinson 1987; cf., e. g., Held/Helfrich 2011; Maaß 2012; Bedijs/Held/Maaß 2014). Concepts like “turn-taking”, “face-enhancing behavior” or “flaming” play a central role particularly in analyzing communication in Internet forums and other commenting genres. Crystal (2011) and Marx/Weidacher (2014) try to merge these different fields of research and even make up a new academic discipline they call Internet linguistics/Internetlinguistik, but it remains to be seen what the real impact of this term will be.

Right from the start of scientific research on online communication, the distinction between orality and literacy was at the center of interest (for the cultural dimension of the distinction between “spoken” and “written” cf. the often quoted study by Ong 1982). The really “new” in the so-called New Media was the phenomenon that a major part of online communication is written, although the features of orality like informality, representations of prosody and the rapidity of exchanging messages cannot be ignored. Furthermore, the physical distance of the communication partners does not relate to linguistic distance, because of the high frequency of communicative immediacy features like little planning effort, emotional and spontaneous utterances or the integration of non-linguistic codes. One of the first questions was therefore if language in the New Media was a new type of writing, or sort of “written speech” (e. g., Maynor 1994; cf. Herring 2007). Some researchers even called it an intermediate type between speech and writing (e. g., Murray 1988). Jacques Anis (1998 and 2002), for example, described online communication as a hybrid between orality and literacy and thus blurring the frontiers (cf. also Yates 1996). Naomi Baron (2008, 48) asked, “Is CMC a form of writing or speech?”, and David Crystal (2011, 21) stated that “Internet language is identical to neither speech nor writing”. Characteristics like abbreviations, nonstandard spellings and emoticons were considered global features for this new communication type. These early globalizing efforts culminated in the attempt to construct a homogeneous language or communication genre referred to as Cyberslang or Netspeak (cf. Abel 22000; Crystal 2001). Also in the Romance languages, terms like langage réseau, cyberlangage, ciberlenguaje, linguaggio cyber emerged (cf. Yus 2001; Dejond 2002 and 2006).

In the later 1990s, it became apparent that communicating “in the Internet” was much more complex than using some abbreviations and emoticons, thus a synoptic term like netspeak was no longer supportable (cf., e. g., Herring 1996 and 2007; Dürscheid 2004). Also a “modes approach”, trying to identify technologically-defined subtypes, was destined to fail, because online communication is sensitive to situational factors as well. Other researchers tried to differentiate with regard to aspects of time and space (cf. Herring 2001 who tried to assign asynchronous forms like e-mail, blogs or online newspapers a position closer to writing, and synchronous like chat or instant messaging a position closer to speaking; cf. also Dürscheid 2003; Denouël 2010 and Knopp 2013; more on this below, chapter 2.1). The focus of linguistic research thus shifted to the description of individual genres of online communication, trying to define the features of communication in each single form. Even if this approach was more realistic and generated significant results, the overall perspective has been somewhat obscured. Particularly well researched communication forms are chat (cf., e. g., Beißwenger 2001; Anis 2002; Pierozak 2003a and 2003b; Thaler 2003 and 2012; Pistolesi 42010; Luckhardt 2009; Kailuweit 2009; Spelz 2009), e-mail (cf., e. g., Ziegler/Dürscheid 22007; Pistolesi 2004; Frehner 2008; Schnitzer 2012; Dürscheid/Frehner 2013) and text messaging/SMS (cf., e. g., Almela Pérez 2001; Anis 2001; 2002; 2007; Schlobinski et al. 2001; Schlobinski 2003; Pistolesi 2004; Schnitzer 2012; as general overview cf. Thurlow/Poff 2013). In each of these forms, approaches from different research areas can be observed, as, e. g., sociolinguistics (cf., e. g., Androutsopoulos 2006), especially the research of youth language (cf., e. g., Baron 2008) and pragmatics (cf., e. g., Thurlow 2003; Androutsopoulos 2007; Anis 2007; Cougnon 2011). Also a lot of Variational Linguistics research was done (cf., e. g., Anis 2004; Liénard 2005; Bieswanger 2006; Cougnon 2008; Cougnon/Ledegen 2010). Only in the last few years have Social Networks shifted into the public eye (cf. Millerand/Proulx/Rueff 2010; Storrer 2013; Bedijs/Held/Maaß 2014; Overbeck 2012; 2014; forthcoming). Social Networks, however, have highlighted the problem with “genre” classifications, because they represent rather complex platforms for user-generated content than clearly definable genres or forms. Like recent analyses show, it is furthermore too narrow a perspective to split communication into “oral” and “literal” (cf. Cougnon/Ledegen 2008); instead, online communication has to be considered on a continuum according to the communicative situation. To this end, the linguistic character of online communication has to be seen as depending largely on the communicative situation of transmitter and receiver.

2Romance perspectives on online communication

2.1Established models

In the course of the emerging New Media, the widely spread Koch/Oesterreicher model on communicative distance and immediacy (based on Söll 31985 [1974], cf. Koch/Oesterreicher 1985; 2001; 2007a; 2007b; 2008; 22011; 2012) was reviewed in regard to the new communication forms. The differentiation between the dichotomy of written/graphic and spoken/phonic code and the conceptional scale between the two poles of communicative distance and communicative immediacy worked well with traditional text forms, but was it also suitable for e-mail, chat or blog communication? Early analyses dealt mainly with such forms of online communication which provided many examples showing the opposite of the prototypical allocation communicative immediacy/phonic code and communicative distance/graphic code. The chat, for instance, is an example for realization in the graphic code in spite of its informality (cf. Pierozak 2003a; 2003b; Thaler 2003; Kailuweit 2009). Because of its synchronous character, the chat seems to be very typical for communicative immediacy with its features of a high degree of emotionality, spontaneity and thus informality, little planning effort and the lack of thematic fixation. Also SMS are considered to represent communicative immediacy, mainly because of their often private and informal character and their spatial limitation (cf. Thurlow/Poff 2013). The reproach of strong deviations from linguistic standard, however (cf. Dittmann/Siebert/Staiger 2007; Anis 2007), could be disproved meanwhile by corpus analyses (cf., e. g., Dürscheid/Stark 2013 and their corpus of Swiss text messages; cf. also Dürscheid/Stark 2011, and chapter 2.2 and 2.3 below). Other forms of online communication, e. g., email or posts in an Internet forum, were more difficult to locate on the immediacy-distance continuum, because their linguistic appearance depends to a large extent on factors like content, topic and motive of writing, and they are thus neither typical for communicative immediacy nor for distance.

Thus the Koch/Oesterreicher model works also with online communication forms, but only partially and depending on the character of the respective communication context. Therefore, several studies tried to revise the model. Three of them will be represented in the following paragraphs as examples for Romance and German perspectives on the topic (as an overview cf. also Overbeck 2012 and 2014).

An early attempt was Kattenbusch’s proposition to replace the phonic code through a so-called “lalischer Code” [‘lalic code’], from the greek lalia ‘small talk’, cf. Kattenbusch 2002). For him, the Koch/Oesterreicher model is not able to respond to specific requirements particularly from forms like chat, e-mail and newsgroup communication, because they include non-linguistic elements that are not classifiable on the conceptional scale. Therefore, online communication functions, according to Kattenbusch, mainly in the graphic medium, wherefore he replaces the phonic code through the lalic code, defined as a hybrid between graphic code and iconographic code (cf. Kattenbusch 2002, 192) and containing elements like emoticons, acronyms and other non-linguistic signs. His proposition of a new model has the same hierarchical structure as the Koch/Oesterreicher model, but with the new conception of the lalic code:

This proposition did not gain acceptance, being mainly criticized because of the dichotomy between graphic and lalic code: also the graphic code contains many iconographic elements like arrows, currency symbols etc. (cf., e. g., Kailuweit 2009). What is more, the number of iconographic elements is, seen in the context of all online communication, rather small and not typical only for communication in the New Media. In times of ongoing technical evolution, the phonic code is furthermore increasingly important, e. g., in communication forms like videoblog or Internet telephony.

In the Koch/Oesterreicher model, Dürscheid mainly regretted the absence of consideration of the influence from time and space on the linguistic features of the different types of online communication (Fig. 2, cf. Dürscheid 2003 and 2004). She underlined the importance of the medium chosen to communicate, with regard to the concrete means of communication following Holly (1997). As far as time and space are concerned, she differentiates between asynchronous forms of communication in different communicative spaces like e-mail, fax message or SMS, and synchronous forms performed in a common communicative space like traditional telephony. In between, she places a so-called quasi-synchronous communication in which the communicative space is common and the communication takes place synchronously, but some features of face-to-face communication are not given, like the possibility to interrupt the communication partner directly. This is the case for forms like chat and instant messaging.

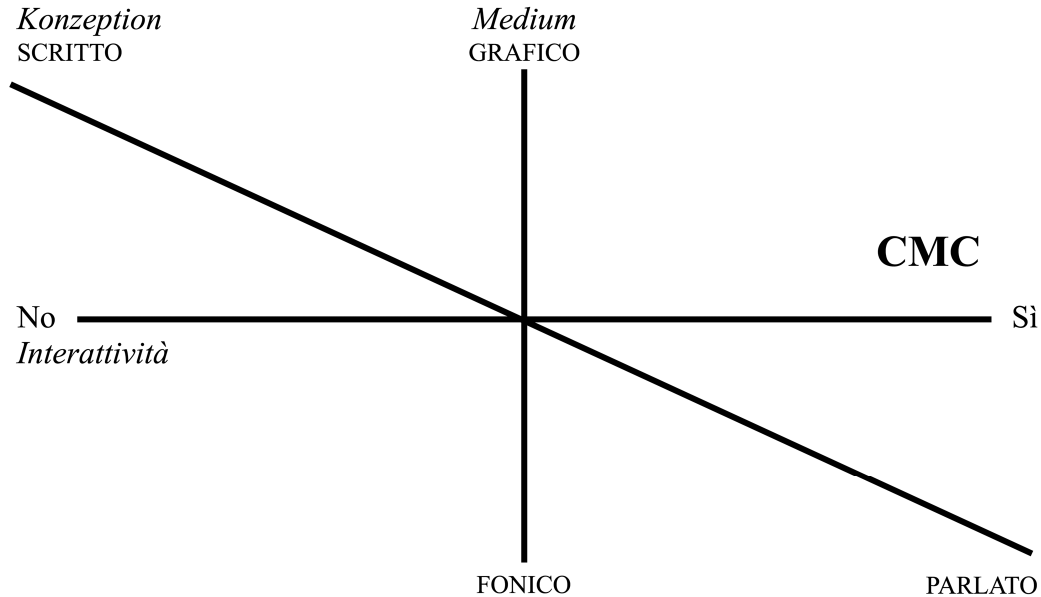

Another element of description was added by Berruto (2005) who proposed to take into consideration the degree of interactivity when describing forms of online communication:

Thus some forms were more interactive than others, above all the chat to which Berruto mainly refers. But he does not consider the growing importance of interaction also in forms characterized so far as less interactive like online newspapers or blogs which offer the opportunity to comment on the content itself, increasingly adopted by users of all types. Meanwhile, there is a lot of interactivity on Social Networks as well, e. g., in Twitter, commenting on a current event like a royal wedding, a thunderstorm or an election. The growing importance of new combined formats like WhatsApp shows the inadequacy of two-dimensional models all failing in the long run due to their dichotomized structure that tries to classify different forms of online communication within one universal scheme and does not leave any place for hybrid types.

Thus, former communication models have to be revised in an era of ongoing media convergence. Of course, one can try to distinguish between “more phonic” forms (Internet telephony like Skype, webradio etc.) and “more graphic” forms (chat, e-mail, text messaging, online journals, e-books), but the increasing number of mixed or hybrid forms (video portals like YouTube, MyVideo; photoblogs like Instagram, Flickr; new forms of instant messaging like WhatsApp, Viber; voice-over-IP communication like Skype, FaceTime etc.) blur the traditional dividing lines. In terms of communicative parameters, we will find also in online communication characteristics of communicative immediacy and distance, but the linguistic approach has to be overarching without any attempt to assign particular communication forms to one of the two poles and to fix them there (cf. Overbeck 2014). New models thus have to overcome the unilateral dichotomized reasoning in order to overcome the frontiers of single communication forms.

2.2New research models and methods

As a reaction to the problems outlined in the previous chapter, Herring (2007, cf. also 2001 and 2002) provided a faceted classification scheme for online communication forms that is based on traditional discourse analysis (cf., e. g., the communication model for spoken discourse classification of Hymes 1974) and extended to what she calls “computer-mediated discourse analysis (CMDA)”, including key features of online communication into the conventional models with the goal to complement existing mode-based communication models. She starts from the generally accepted assumption that the appearance of online communication is subject to two basic types of influence: the medium as technological aspect and the situation as a social one. Their relationship is considered to be non-hierarchical and dependent on different contexts. Herring thus builds up two open-ended sets of categories, the “medium factors” and the “situation factors”:

Table 1: Medium factors (Herring 2007)

| M1 | Synchronicity |

| M2 | Message transmission (1-way vs. 2-way) |

| M3 | Persistence of transcript |

| M4 | Size of message buffer |

| M5 | Channels of communication |

| M6 | Anonymous messaging |

| M7 | Private messaging |

| M8 | Filtering |

| M9 | Quoting |

| M10 | Message format |

All factors are technically independent of one another, but in practice, they tend to combine and correlate. This faceted classification scheme functions well with what Herring calls “familiar CMC modes”, as, e. g., the Internet Relay Chat. She describes this communication form as being typically many-to-many, having a high degree of anonymity, social in function and non-serious in tone, containing a high incidence of phatic exchanges and utilized particularly by young people between 18 and 25 years. Even with more sophisticated forms like the blog, this classification may help to define communication features, as it is shown in the exemplary sample classification Herring represents in her article. But when applying this model to even more complex forms of online communication, it becomes evident that also the definition of medium and situation factors can only be an approximation that obscures many aspects of social, psychological and also technical contexts. Taking into account, for example, the complexity of platforms like Twitter, Facebook or Google+, it becomes obvious that even the different facets can only give an idea of the great versatility of modern online communication. What is more, the scheme is based primarily on research findings for textual online communication and excludes again the hybrid forms like mobile and voice-over-IP communication. With this ongoing advancement, new varieties of discourse are created that call out for analysis and further classification.

Table 2: Situation factors (Herring 2007)

| S1 | Participation structure | – | One-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-many |

| – | Public/private | ||

| – | Degree of anonymity/pseudonymity | ||

| – | Group size; number of active participants | ||

| – | Amount, rate, and balance of participation | ||

| S2 | Participant characteristics | – | Demographics: gender, age, occupation, etc. |

| – | Proficiency: with language/computers/CMC | ||

| – | Experience: with addressee/group/topic | ||

| – | Role/status: in “real life”; of online personae | ||

| – | Pre-existing sociocultural knowledge and interactional norms | ||

| – | Attitudes, beliefs, ideologies, and motivations | ||

| S3 | Purpose | – | Of group, e.g., professional, social, fantasy/role-playing, aesthetic, experimental |

| – | Goal of interaction, e.g., get information, negotiate consensus, develop professional/social relationships, impress/entertain others, have fun | ||

| S4 | Topic or Theme | – | Of group, e.g., politics, linguistics, feminism, soap operas, sex, science fiction, South Asian culture, medieval times, pub |

| – | Of exchanges, e.g., the war in Iraq, pro-drop languages, the project budget, gay sex, vacation plans, personal information about participants, meta-discourse about CMC | ||

| S5 | Tone | – | Serious/playful |

| – | Formal/casual | ||

| – | Contentious/friendly | ||

| – | Cooperative/sarcastic, etc. | ||

| S6 | Activity | – | E.g., debate, job announcement, information exchange, phatic exchange, problem solving, exchange of insults, joking exchange, game, theatrical performance, flirtation, virtual sex |

| S7 | Norms | – | Of organization |

| – | Of social appropriateness | ||

| – | Of language | ||

| S8 | Code | – | Language, language variety |

| – | Font/writing system |

This position is supported by Jucker/Dürscheid (2012) who also underline that the traditional analytical categories distinguishing between different forms of communication are no longer sustainable in their entirety. These categories were (cf. Jucker/Dürscheid 2012, chapter 2):

a)asynchronous vs. synchronous

b)written vs. spoken

c)monologic vs. dialogic

d)text vs. utterance

e)public vs. private

f)mobile vs. stationery

g)monomodal vs. multimodal.

Not all categories are of equal value, some of them being blurred because of the ongoing media convergence. What is more, some categories influence each other, which is particularly important for the degree of orality: The more synchronous a communication takes place, the more “oral” it might be in conception. The same applies to the degree of publicity, thus the distinction is not supportable in all aspects.

With the advent of smartphones, the distinction between mobile vs. stationary has also become outdated. Also the dichotomy between “public” and “private” is no longer sustainable, because there is rather a difference between public and nonpublic that refers to the accessibility of the communication, while private vs. non-private rather refers to the nature of the content of a message. Jucker/Dürscheid (2012, 44s.) distinguish between three dimensions: the communicative situation (the scale of public accessibility), the content (the scale of privacy) and the linguistic realization (the scale of communicative immediacy).

With regard to the dichotomy between asynchronicity and synchronicity, the authors not only add the already-mentioned third possibility of quasi-synchronicity (cf. Dürscheid 2003, as further explained above), but they suggest a new three-level distinction of co-presence, synchronicity and simultaneity (Jucker/Dürscheid 2012, 43). In this sense, co-presence means the engagement of the communication interactants at the same time, but not necessarily in the same location. The level of synchronicity refers to the timing of production and reception of the message, while simultaneity prevails if two or more messages are produced (and even received) at the same time. The latter is of special interest for the very new forms of online communication like WhatsApp or Viber that combine written and oral message production and are sometimes used in a simultaneous communication context. These three factors can influence the linguistic appearance of the messages, because co-presence and simultaneity increase the velocity of the communication and may produce more features of closeness or immediacy: The spontaneity of the interaction is intensified by the recurrent use of emoticons and emojis representing items like plants, buildings, food or people.

Together with “written” vs. “spoken”, the distinction between “texts” and “utterances” is no longer useful, following Jucker/Dürscheid, because in online communication, the boundary blurs between graphically-realized texts, tending to be monologic, planned and rather used in asynchronous communication, and phonically-produced utterances, occurring rather in dialogic contexts and synchronous communication, tending to be short and spontaneous. The authors propose the more general term “communicative act” (CA) referring to the Relevance Theory of Sperber/Wilson (21995). The term CA is defined as

“a more general designation that covers language units irrespective of their monologic or dialogic context, irrespective of their synchronous, quasi-synchronous or asynchronous communication pattern, and ultimately also irrespective of their production in the graphic or phonic code or even in a non-verbal manner” (Jucker/Dürscheid 2012, 46).

The authors replace the dichotomy of monologic vs. dialogic contexts with a scale of uptake expectations, in other words, “communicative acts differ as to the extent to which their producers can expect other communicators to respond”:

In addition, the authors differentiate CAs that occur in relative isolation (e. g., like books, user manuals, church sermons or academic talks) from others that are “generally embedded in a whole string of related units, e. g., chat contributions or tweets” (ibid., 47). The latter are designated as “communicative act sequences” (CAS). With the help of this new term, it is possible not only to cover “traditional” sequences like face-to-face conversations or letters, but also a large part of online communication in context like an e-mail exchange, a text message dialogue, a timeline on Twitter or a thread in an Internet forum. Moreover, Jucker/Dürscheid introduce the useful technical distinction between single-tool platforms such as e-mail, chat, blog or SMS, and multiple-form platforms like most of the Social Networks, but also Skype or online newspapers. In the latter, a range of different types of communication forms is available at the same time (e. g., profile, chat function and “like” button on Facebook, comments or links to weather forecasts in online newspapers etc.), so they provide the basis of the mentioned CAS:

That the given definitions work with most of the new and very new forms of online communication is shown in the case studies given in the cited article (mainly on Facebook and Twitter).

As the propositions of Herring and Jucker/Dürscheid show, future models will have to overcome the traditional dichotomy between “written” and “oral”. Earlier categories used to analyze different forms of communication are no longer valid, because new forms of online communication transverse the frontiers between the once rather clearly separated text and communication forms. We must accept the impossibility to categorize all forms of online discourse in one clear and durable classification scheme (cf. also Overbeck 2014). Thus, the distinct disciplines have to strengthen their effort to work together in an interdisciplinary way. First attempts are already evolving through several research networks collecting data to build large, publicly-accessible corpora, as is shown in the following section.

2.3Sources for research

To improve the knowledge about language in online communication, the construction of theoretical models has to be based on detailed analyses of computer-mediated data samples and collections. At the present time, the range of large accessible corpora for the analysis of online communication is rather unsatisfactory, even though a growing number of researchers and research groups dedicate themselves to different linguistic and social aspects. Among these, we can differentiate two types of scientific approaches:

1)Project-related data, e. g., for corpus-based doctoral theses or other more individual scientific works. For the most part, these are not publicly available, but partly accessible via the (sometimes online) published works (cf., e. g., for French chats Pierozak 2003a and 2003b; for German chats Thaler 2003 and Luckhardt 2009; for German-Swedish chats Pankow 2003; for English SMS Tagg 2009; for Twitter Tagg/Mason 2011 (English) and Overbeck 2012 (Italian, French and German); for English computer conferencing cf. the CoSy:50 Corpus from Yates 1996; for mixed German data analyses cf. Bittner 2003 and the related site <http://www.digitalitaet.net> that offers several little (older) corpora on chat, e-mail and private homepages).

2)“Publicly” collected data for general use from research groups or public institutions that are available online and mostly depend on the cooperation of the general public (e. g., donation of SMS). Some of these corpora are of considerable size and already form the basis of a growing number of analyses. It is surprising that especially the SMS as a rather “private” and difficultly accessible communication form seems to be the best investigated type: At the University of Münster, the Centrum Sprache und Interaktion constructed in 2012 a Datenbank für Alltagskommunikation in SMS85 (database for everyday communication in SMS), but it is dedicated only to the lectures of the German Institute of the university. An early public project was the Belgian initiative Faites don de vos SMS à la science that collected 30,000 SMS, published on CD-ROM in 2006 (cf. Fairon/Klein/Paumier 2006; Cougnon 2008; Cougnon/Bouraoui ↗8 Orality and Literacy of Telephony and SMS). The Belgian-Swiss-German project sms4science86 has collected 25,947 SMS (ca. 500,000 tokens) in German, French, Italian and Romansh (41% of all SMS are in Swiss German dialect, 28% in non-dialectal German, 18% in French, 6% in Italian, and 4% in Romansh) which were sent in by the Swiss public in the years 2009/2010 and are now publicly accessible (cf. Dürscheid/Stark 2011 and 2013; Stähli/Dürscheid/Béguelin 2011). The successor project is named What’s up, Switzerland?,87 founded in 2013 at the universities of Bern, Zurich and Neuchâtel and dedicated to WhatsApp. The aim of the project is to describe the linguistic features of WhatsApp communication and to compare it with the SMS collected in sms4science. The key questions are the following:

–How are different languages and dialects used in WhatsApp messages?

–How do WhatsApp users interact with each other?

–How do WhatsApp chats differ from SMS?

–Do new technologies bring about linguistic changes? And if so, what kind of changes?

Thus, the project combines linguistic aspects with technical and social ones and we can be curious what the results will be in this innovative approach.

Another remarkable corpus being composed in Italy is the TWITA88 corpus comprising at the moment more than 155 million of Italian tweets collected from February 2012 to June 2013 and offering partial geo-location information as well. Regarding (Italian) chat, also the Eulogos Corpus di conversazioni da chat-line in lingua italiana89 is worth mentioning.

It is surprising that for other communication forms like e-mail, blogs, online telephony, online journals, etc. accessible corpora of greater size are rather rare. One can find several little projects offering a selection of data, like, e. g., the Birmingham Blog Corpus,90 the Düsseldorf CMC Corpus (as described in Zitzen 2004), or the Dortmunder Chat-Korpus,91 but within the overall framework, large corpora for general use and interdisciplinary studies are still missing. Also projects and corpora in the Roman context are still quite rare, while the research environment in German and Anglophone contexts seems to be more productive at present, as several academic project networks show, cf., e. g., the interdisciplinary project Analyse von Diskursen in Social Media92 [‘Analysis of Discourse in Social Media’] in which academics from both Communication Sciences and Linguistics are involved. The goal of the project network is to develop and evaluate an automated process in order that different approaches can be applied in answering questions about online communication studies. Michael Beißwenger and Angelika Storrer give a useful overview on available corpora in their article “Corpora of Computer-Mediated Communication” (Beißwenger/Storrer 2008).

3Conclusions, perspectives and desiderata

3.1Short resume

When exploring online communication at present, one has always to keep in mind that communication in the New Media is in most cases no longer a simple transmission of a message from the sender to the receiver, but a new form of interaction with many participants who create, comment and discuss meaning (cf. Jucker/Dürscheid 2012). In this sense, the traditional categories applied in the past to distinguish between different forms of communication cannot be transferred to the entirety of online communication. Even the attempt to think in categories is doomed to fail in times of increasing media convergence. Particularly the very new forms of online communication like WhatsApp or Viber, which combine written messages with photo, video or voice messages, refuse any clear categorization. Also, most of the Social Networks are changing into multiple-tool-platforms that bundle several communication practices like chat, status updates, private messages, buttons for sharing, commenting functions, etc. that are no longer separable from one another. In these cases, we will have to talk about communicative act sequences transcending single communication platforms rather than about communication forms. The increasing number of interdisciplinary corpora will be a first step to get an overview about the work to do in the next decades of research about online communication.

3.2Linguistic change?

As the first analyses have shown, the linguistic change caused by the New Media is nothing to worry about concerning aspects like linguistic paucity or the loss of grammatical standards. The technical evolution, of course, has a considerable influence on social relationships, the construction of different identities and not least on language behavior, but the fears of language decline, mainly concerning the younger generation, seem to be exaggerated. Like several scientific studies confirmed, there is no deterioration of the writing skills of pupils detectable (cf. Brommer/Dürscheid 2009; Plester/Wood/Joshi 2009; Dürscheid/Wagner/Brommer 2010; Storrer 2010; Dürscheid/Stark 2013). Young people normally adapt themselves to communication contexts and control the selection of linguistic registers, also in times of SMS, WhatsApp and Facebook. Thus, the language use also in online communication depends to a large part on the medium chosen to communicate and the context of communication.

What is more, the analyses could not detect any influence of the informal writing patterns in many forms of online communication on text types requiring linguistic complexity and formality (cf. Storrer 2010). On the contrary, in the long run a diversification of text types and a functional extension of writing styles will most likely result from the high degree of varieties in online discourses.

These varieties are, on the other hand, not compressible into one single language like “netspeak”. As the last two decades of the analysis of online communication have clearly demonstrated, the features meant to be typical for online communication, like emoticons, abbreviations, acronyms etc., can be found also in other linguistic fields. What is more, these features are high-frequency only in the communication of the leisure and private sector, being considerably less frequent in more formal contexts of use (e. g., Internet forums in the educational or scientific sector, online counseling chats, political blogs, newsletters etc.). It is thus not possible to designate the diversity of features of online communication with one general term: “online communication” is not a language.

3.3Perspectives

Thus, actual research on online communication will have to rethink the existing models and choose a new access that overcomes the old dichotomous structures. In an era of smartphones with growing displays, even the medium chosen for communication is no longer decisive for the linguistic quality of the conversation: Supported by lots of applications, the mobile phone (or tablet) is by now able to offer all sorts of online communication formerly only possible on the desktop PC. Thus, the constraints of the small display and the restrained keyboard are becoming less and less important. A new linguistic framework will thus have to address technical challenges in future classification models respecting that online communication can use multiple channels of communication at the same time. Multimodal forms are on the rise, and users have become accustomed to operate with two or more modes at the same time. Examples for this are not only the Social Networks with their multiple tools, but also video blogs or instant messaging forms combining language, images, music and sounds. Other hybrid modes where participants can speak, write and use audio channels at the same time are, e. g., the multiplayer online games or Multi User Dungeons (MUDs). To integrate all these forms, future research will have to adopt a transdisciplinary perspective and include several scientific disciplines, not only Linguistics, but also Information Science and other technical fields.

For this purpose, interdisciplinary projects will have to build corpora for analysis and research. The aim of all corpus-based analyses should be the greatest possible accessibility of the collected data and the cross-linkage of as many projects as possible to offer a basis for interdisciplinary work. At the present time, too much useful data gets lost because of the “privacy” of individual research. Very desirable is also the elaboration of consistent methods for data sampling (many suggestions are given in Herring 2004 and Beißwenger/Storrer 2008). Rather than collect and represent raw data, it would be best to find a standardized annotation scheme and to develop appropriate categories for the description of linguistic, namely grammatical features of the language in online communication (e. g., morphosyntactic taggers). Online communication corpora thus need special devices because of the often-noticed deviations from standard language (typing errors, abbreviations, special use of punctuation etc.) and the multiple variations in lexical and morphological elements. Another characteristic is the presence of system-generated content that does not belong to the linguistic register and thus has to be separated (nicknames, labeled quotations, system messages etc.). Also meta-information about the users of different online communication forms should be registered (if available), because it can be of great importance for sociological or psychological studies as well as for sociolinguistic analyses (correlations between age, gender and level of education of the users and their stylistic and linguistic features).

In this sense, data from online communication corpora should also been included into the great national corpora of contemporary language. At present, neither the British National Corpus (BNC), nor the German corpora available through the COSMAS93 search tool or the online corpus of the German language of the 20th century compiled within the framework of the online dictionary project DWDS do so (cf. Beißwenger/Storrer 2008). Also, the important Romance corpora like Frantext, Corpus di Italiano Scritto (CORIS), Corpus e Lessico di Frequenza dell’Italiano Scritto (CoLFIS), Corpus del Español Actual (CEA), Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual (CREA), or Corpus de Referência do Português Contemporâneo (CRPC) should offer, in the long run at least, a certain percentage of online communication data.

The future prospect for research on online communication is thus the widening of the perspective in all senses, always along the ongoing technical evolution.

4References

Abel, Jürgen (22000), Cybersl@ng. Die Sprache des Internet von A–Z, München, Beck.

Adamzik, Kirsten (2000), Textsorten. Reflexionen und Analysen, Tübingen, Stauffenburg.

Almela Pérez, Ramón (2001), Los sms: Mensajes cortos en la telefonía móvil, Español Actual – Revista de Español vivo 75, 91–99.

Androutsopoulos, Jannis (2006), Introduction. Sociolinguistics and computer-mediated communication, Journal of Sociolinguistics 10:4, 419–438.

Androutsopoulos, Jannis (2007), Neue Medien. Neue Schriftlichkeit?, Mitteilungen des Germanistenverbandes 54:1, 72–97.

Androutsopoulos, Jannis (2013), Code-switching in computer-mediated communication, in: Susan C. Herring/Dieter Stein/Tuija Virtanen (edd.), Handbook of the Pragmatics of Computer-Mediated Communication, Berlin/Boston, de Gruyter, 667–694.

Anis, Jacques (1998), Texte et ordinateur: l’écriture réinventée?, Paris, De Boeck.

Anis, Jacques (2001), Parlez-vous texto?, Paris, Le Cherche Midi.

Anis, Jacques (2002), Communication électronique scripturale et formes langagières. Chats et sms, in: Actes des Quatrièmes Rencontres Réseaux Humains/Réseaux technologiques, Poitiers, Université de Poitiers, <http://rhrt.edel.univ-poitiers.fr/document.php?id=547> (16.12.2016).

Anis, Jacques (2004), Les abréviations dans la communication électronique (en français et en anglais), in: Nelly Andrieux-Reix et al. (edd.), Écritures abrégées (notes, notules, messages, codes...), Paris, Ophrys, 97–112.

Anis, Jacques (2006), Communication électronique scripturale et formes langagières, RHRT 4, <http://rhrt.edel.univ-poitiers.fr/document.php?id=547> (19.03.2017).

Anis, Jacques (2007), Neography. Unconventional Spelling in French SMS Text Messages, in: Brenda Danet/Susan C. Herring (edd.), The Multilingual Internet. Language, Culture and Communication Online, New York, Oxford University Press, 87–115.

Auzanneau, Michelle/Juillard, Caroline (2012), Jeunes et parlers jeunes: catégories et catégorisations, Langage et société 141:3, 5–20.

Baron, Naomi (1984), Computer-mediated communication as a force in language change, Visible Language 18, 118–141.

Baron, Naomi (2008), Always on: Language in an Online and Mobile World, Oxford, University Press.

Bedijs, Kristina/Held, Gudrun/Maaß, Christiane (edd.) (2014), Face Work and Social Media, Münster et al., LIT.

Beißwenger, Michael (ed.) (2001), Chat-Kommunikation. Sprache, Interaktion, Sozialität & Identität in synchroner computervermittelter Kommunikation, 2 vol., Stuttgart, Ibidem.

Beißwenger, Michael (2007), Corpora zur computervermittelten (internetbasierten) Kommunikation, Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik 35:3, 496–503.

Beißwenger, Michael/Storrer, Angelika (2008), Corpora of Computer-Mediated Communication, in: Anke Lüdeling/Merja Kytö (edd.), Corpus Linguistics. An International Handbook, vol. 1, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter, 292–308.

Berruto, Gaetano (2005), Italiano parlato e comunicazione mediata dal computer, in: Klaus Hölker/Christiane Maaß (edd.), Aspetti dellʼitaliano parlato, Münster/Zürich, LIT, 137–156.

Bieswanger, Markus (2006), 2 abbrevi8 or not 2 abbrevi8. A contrastive analysis of different space and time-saving strategies in English and German text messages, Texas Linguistic Forum 50, 1–12.

Bittner, Johannes (2003), Digitalität, Sprache, Kommunikation. Eine Untersuchung zur Medialität von digitalen Kommunikationsformen und deren varietätenlinguistischer Modellierung, Berlin, Schmidt (cf. also the related site <http://www.digitalitaet.net>, 16.12.2016).

Boyer, Henri (2007), Les médias et le “français des jeunes”: intégrer la dissidence?, in: Eva Neuland (ed.), Jugendsprachen: mehrsprachig – kontrastiv – interkulturell, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang, 153–163.

Brinker, Klaus (1993), Textlinguistik, Heidelberg, Groos.

Brinker, Klaus, et al. (ed.) (2000), Text- und Gesprächslinguistik, vol. 1, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter.

Brommer, Sarah/Dürscheid, Christa (2009), Getippte Dialoge in neuen Medien. Sprachkritische Aspekte und linguistische Analysen, Linguistik Online 37:1, <http://www.linguistik-online.de/37_09/duerscheidBrommer.pdf> (16.12.2016).

Brown, Penelope/Levinson, Stephen C. (1987), Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Centrum Sprache und Kommunikation der Universität Münster (2012), SMS-Datenbank zur Alltagskommunikation mit SMS, <http://cesi.uni-muenster.de/~SMSDB> (16.12.2016).

Cougnon, Louise-Amélie (2008), Le français de Belgique dans l’écrit spontané. Approche syntaxique et phonétique d’un corpus de SMS, Travaux du Cercle Belge de Linguistique 3, <http://sites.uclouvain.be/bkl-cbl/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/cou2008.pdf> (16.12.2016).

Cougnon, Louise-Amélie (2011), “Tu te prends pour the king of the world?”. Language contact in text messaging context, in: Cornelius Hasselblatt/Peter Houtzagers/Remco van Pareren (edd.), Language contact in times of globalisation, Amsterdam/New York, Rodopi, 45–59.

Cougnon, Louise-Amélie/Ledegen, Gudrun (2010), “C’est écrire comme je parle”. Une étude comparatiste de variétés de français dans l’“écrit sms”, in: Michaël Abecassis/Gudrun Ledegen (edd.), Les Voix des Français. En parlant, en écrivant, vol. 2, Oxford et al., Lang, 39–58.

Crystal, David (2001), Language and the Internet, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Crystal, David (2011), Internet Linguistics: A Student Guide, London/New York, Routledge.

Dejond, Aurélia (2002), La cyberl@ngue française, Tournai, Renaissance du Livre.

Dejond, Aurélia (2006), Cyberlangage, Bruxelles, Racine.

Denouël, Julie (2010), Communication électronique et coprésence à distance, Saarbrücken, Éditions universitaires européennes.

Dittmann, Jürgen/Siebert, Hedy/Staiger, Yvonne (2007), Medium und Kommunikationsform – am Beispiel der SMS, Networx 50, <http://www.mediensprache.net/networx/networx-50.pdf> (16.12.2016).

Döring, Nicola (1997), Kommunikation im Internet. Neun theoretische Ansätze, in: Bernad Batinic (ed.), Internet für Psychologen, Göttingen et al., Hogrefe, 267–298.

Döring, Nicola (22003 [1999]), Sozialpsychologie des Internet. Die Bedeutung des Internet für Kommunikationsprozesse, Identitäten, soziale Beziehungen und Gruppen, Göttingen, Hogrefe.

Dürscheid, Christa (2003), Medienkommunikation im Kontinuum von Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit. Theoretische und empirische Probleme, Zeitschrift für Angewandte Linguistik 38, 37–56.

Dürscheid, Christa (2004), Netzsprache – ein neuer Mythos, in: Michael Beißwenger/Ludger Hoffmann/Angelika Storrer (edd.), Internetbasierte Kommunikation, special issue of OBST 68, 141–157.

Dürscheid, Christa/Frehner, Carmen (2013), Email communication, in: Susan C. Herring/Dieter Stein/Tuija Virtanen (edd.), Handbook of the Pragmatics of Computer-Mediated Communication, Berlin/Boston, de Gruyter , 35–54.

Dürscheid, Christa/Stark, Elisabeth (2011), SMS4science: An international corpus-based texting project and the specific challenges for multilingual Switzerland, in: Crispin Thurlow/Kristine Mroczek (edd.), Digital Discourse. Language in the New Media, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 299–320.

Dürscheid, Christa/Stark, Elisabeth (2013), Anything goes? SMS, phonographisches Schreiben und Morphemkonstanz, in: Martin Neef/Carmen Scherer (edd.), Die Schnittstelle von Morphologie und geschriebener Sprache, Berlin/Boston, de Gruyter, 189–209.

Dürscheid, Christa/Wagner, Franc/Brommer, Sarah (2010), Wie Jugendliche schreiben. Schreibkompetenz und neue Medien, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter.

Eckkrammer, Eva Martha (2001), Textsortenkonventionen im Medienwechsel, in: Peter Handler (ed.), E-Text. Strategien und Kompetenzen. Elektronische Kommunikation in Wissenschaft, Bildung und Beruf, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang, 45–66.

Ehlich, Konrad (1981), Text, Mündlichkeit, Schriftlichkeit, in: Hartmut Günther (ed.), Geschriebene Sprache – Funktion und Gebrauch, Struktur und Geschichte, München, Institut für Phonetik und sprachliche Kommunikation, 23–51.

Fairon, Cédrick/Klein, Jean/Paumier, Sébastien (2006), Le Corpus SMS pour la science. Base de données de 30.000 SMS et logiciels de consultation, CD-Rom, Louvain-la-Neuve, Presses universitaires de Louvain.

Fix, Ulla (2011), Aktuelle Tendenzen des Textsortenwandels. Thesenpapier der Sektionentagung der GAL in Bayreuth, <http://www.uni-leipzig.de/~fix/Textsortenwandel.pdf> (16.12.2016).

Frehner, Carmen (2008), Email – SMS – MMS. The Linguistic Creativity of Asynchronous Discourse in the New Media Age, Bern et al., Lang.

Held, Gudrun/Helfrich, Uta (edd.), (2011), Cortesia – politesse – cortesía, La cortesia verbale nella prospettiva romanistica / La politesse verbale dans une perspective romaniste / La cortesía verbal desde la perspectiva romanística. Aspetti teorici e applicazioni / Aspects théoriques et applications / Aspectos teóricos y aplicaciones, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang.

Herring, Susan C. (ed.) (1996), Computer Mediated Communication, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, Benjamins.

Herring, Susan C. (2001), Computer-Mediated Discourse, in: Deborah Schiffrin/Deborah Tannen/Heidi E. Hamilton (edd.), The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, Oxford, Blackwell, 612–634.

Herring, Susan C. (2002), Computer-mediated communication on the Internet, Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 36, 109–168.

Herring, Susan C. (2004), Computer-mediated discourse analysis: An approach to researching online behavior, in: Sasha Barab/Rob Kling/James H. Gray (edd.), Designing for Virtual Communities in the Service of Learning, New York, Cambridge University Press, 338–376.

Herring, Susan C. (2007), A Faceted Classification Scheme for Computer-Mediated Discourse, Language@Internet 4, article 1, <http://www.languageatinternet.org/articles/2007/761> (16.12.2016).

Herring, Susan C./Stein, Dieter/Virtanen, Tuija (edd.) (2013), Handbook of the Pragmatics of Computer-Mediated Communication, Berlin/Boston, de Gruyter.

Holly, Werner (1997), Zur Rolle von Sprache in Medien. Semiotische und kommunikationsstrukturelle Grundlagen, Muttersprache 1, 64–75.

Hymes, Dell (1974), Foundations in sociolinguistics: An ethnographic approach, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Jakobs, Eva-Maria (2003), Hypertextsorten, Zeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik 31, 232–273.

Jucker, Andreas H./Dürscheid, Christa (2012), The Linguistics of Keyboard-to-Screen Communication. A New Terminological Framework, Linguistik Online 6:2, 39–64, <http://www.linguistik-online.com/56_12/juckerDuerscheid.pdf> (16.12.2016).

Kailuweit, Rolf (2009), Konzeptionelle Mündlichkeit? Überlegungen zur Chat-Kommunikation anhand französischer, italienischer und spanischer Materialien, Philologie im Netz 48, <http://web.fu-berlin.de/phin/phin48/p48t1.htm> (16.12.2016).

Kallweit, Daniel (2015), Neografie in der computervermittelten Kommunikation des Spanischen. Zu alternativen Schreibweisen im Chatnetzwerk www.irc-hispano.es, Tübingen, Narr.

Kattenbusch, Dieter (2002), Computervermittelte Kommunikation in der Romania im Spannungsfeld zwischen Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit, in: Sabine Heinemann/Gerald Bernhard/Dieter Kattenbusch (edd.), Roma et Romania: Festschrift für Gerhard Ernst zum 65. Geburtstag, Tübingen, Niemeyer, 183–199.

Knopp, Matthias (2013), Mediale Räume zwischen Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit. Zur Theorie und Empirie sprachlicher Handlungsformen, PhD thesis, Universität zu Köln, <http://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/5150> (16.12.2016).

Koch, Peter/Oesterreicher, Wulf (1985), Sprache der Nähe – Sprache der Distanz. Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im Spannungsfeld von Sprachtheorie und Sprachgeschichte, Romanistisches Jahrbuch 36, 15–43.

Koch, Peter/Oesterreicher, Wulf (2001), Langage parlé et langage écrit, in: Günter Holtus/Michael Metzeltin/Christian Schmitt (edd.), Lexikon der Romanistischen Linguistik, vol. I,2: Methodologie, Tübingen, Niemeyer, 584–627.

Koch, Peter/Oesterreicher, Wulf (2007a), Lengua hablada en la Romania: Español, francés, italiano, Madrid, Gredos.

Koch, Peter/Oesterreicher, Wulf (2007b), Schriftlichkeit und kommunikative Distanz, Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik 35, 346–375.

Koch, Peter/Oesterreicher, Wulf (2008), Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit von Texten, in: Nina Janich, Textlinguistik. 15 Einführungen, Tübingen, Narr, 199–215.

Koch, Peter/Oesterreicher, Wulf (22011 [1990]), Gesprochene Sprache in der Romania: Französisch, Italienisch, Spanisch, Tübingen, Niemeyer.

Koch, Peter/Oesterreicher, Wulf (2012), Language of Immediacy – Language of Distance: Orality and Literacy from the Perspective of Language Theory and Linguistic History, in: Claudia Lange/Beatrix Weber/Göran Wolf (edd.), Communicative Spaces. Variation, Contact, and Change – Papers in Honour of Ursula Schaefer, Frankfurt a. M. et al., Lang, 441–473 (= English version of Koch/Oesterreicher 1985).

Liénard, Fabien (2005), Langage texto et langage contrôlé. Description et problèmes, Linguisticae Investigationes 28:1, 49–60.

Linke, Angelika/Nussbaumer, Markus/Portmann, Paul R. (52004 [1994]), Studienbuch Linguistik, Tübingen, Niemeyer.

Luckhardt, Kristin (2009), Stilanalysen zur Chat-Kommunikation: eine korpusgestützte Untersuchung am Beispiel eines medialen Chats, PhD thesis, TU Dortmund, <http://eldorado.tu-dortmund.de:8080/bitstream/2003/26055/2/Schlussfassung.pdf> (16.12.2016).

Maaß, Christiane (2012), Der anwesende Dritte im Internetforum zwischen potentieller Sprecherrolle und “non-personne”, in: Kristina Bedijs/Karoline Henriette Heyder (edd.), Sprache und Personen im Web 2.0, Münster, LIT, 65–85.

Marx, Konstanze/Weidacher, Georg (2014), Internetlinguistik. Ein Lehr- und Arbeitsbuch, Tübingen, Narr.

Maynor, Natalie (1994), The Language of Electronic Mail: Written Speech, in: Greta D. Little/Michael Montgomery (edd.), Centennial Usage Studies, Tuscaloosa (AL), University of Alabama Press, 48–54.

Millerand, Florence/Proulx, Serge/Rueff, Julien (edd.) (2010), Web social. Mutation de la communication, Québec, Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Murray, Denise E. (1988), The context of oral and written language: A framework for mode and medium switching, Language in Society 17, 351–373.

Neuland, Eva (ed.) (2003), Jugendsprachen – Spiegel der Zeit, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang.

Neuland, Eva (ed.) (2007), Jugendsprachen: mehrsprachig – kontrastiv – interkulturell, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang.

Neuland, Eva (2008), Jugendsprache. Eine Einführung, Tübingen, Francke.

Ong, Walter J. (1982), Orality and Literacy. The Technologizing of the Word, London/New York, Methuen.

Overbeck, Anja (2012), “Parlez-vous texto?” Soziale Netzwerke an der Schnittstelle zwischen realem und virtuellem Raum, in: Annette Gerstenberg/Claudia Polzin-Haumann/Dietmar Osthus, Sprache und Öffentlichkeit in realen und virtuellen Räumen, Bonn, Romanistischer Verlag, 217–247.

Overbeck, Anja (2014), “Twitterdämmerung”. Versuch eines Klassifikationsschemas polyfunktionaler Kommunikationsformen, in: Nadine Rentel/Ursula Reutner/Ramona Schröpf (edd.), Von der Zeitung zur Twitterdämmerung. Medientextsorten und neue Kommunikationsformen im deutschfranzösischen Vergleich, Münster, LIT, 207–228.

Overbeck, Anja (2015), La communication dans les médias électroniques, in: Claudia Polzin-Haumann/Wolfgang Schweickard (edd.), Manuel de linguistique française, Berlin/Boston, de Gruyter, 275–292.

Overbeck, Anja (forthcoming), “Dann geh doch zu Twitter und such dir nen Ritter”. Grenzüberschreitungen in den Sozialen Medien, in: Nadine Rentel/Tilman Schröder (edd.), Akten der Sektion “Sprache und digitale Medien: Grenzbeziehungen und Brückenschläge von Sprache zwischen digitalem und analogem Raum” (Frankoromanistentag Saarbrücken 28.09.–01.10.2016).

Pankow, Christiane (2003), Zur Darstellung nonverbalen Verhaltens in deutschen und schwedischen IRC-Chats. Eine Korpusuntersuchung, Linguistik Online 15:3, <http://www.linguistik-online.de/15_03/pankow.pdf> (16.12.2016).

Pierozak, Isabelle (2003a), Le “français tchaté”: un objet à géométrie variable?, Langage & société 104, 123–144.

Pierozak, Isabelle (2003b), Le français tchaté. Une étude en trois dimensions – sociolinguistique, syntaxique et graphique – dʼusages IRC, Thèse d’état, Université dʼAix-Marseille.

Pistolesi, Elena (42010 [2004]), Il parlar spedito. Lʼitaliano di chat, e-mail e SMS, Padova, Esedra.

Plester, Beverly/Wood, Clare/Joshi, Puja (2009), Exploring the relationship between children’s knowledge of text message abbreviations and school literacy outcomes, British Journal of Developmental Psychology 27, 145–161.

Rehm, Georg (2006), Hypertextsorten. Definition – Struktur – Klassifikation, PhD thesis, Universität Gießen, <http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2006/2688/pdf/RehmGeorg-2006-01-23.pdf> (16.12.2016).

Rheingold, Howard (1993), The virtual community: homesteading on the electronic frontier, Reading (MA), Addison Wesley.

Rheingold, Howard (1995), The virtual community: finding connection in a computerized world, London, Minerva.

Rice, Ronald E./Hughes, Douglas/Love, Gail (1989), Usage and outcomes of electronic messaging at an R&D organization: Situational constraints, job level, and media awareness, Office: Technology and People 5:2, 141–161.

Schlobinski, Peter (2003), SMS-Texte – Alarmsignale für die Standardsprache?, <http://www.mediensprache.net/de/essays/2/#fn1> (16.12.2016).

Schlobinski, Peter, et al. (2001), Simsen. Eine Pilotstudie zu sprachlichen und kommunikativen Aspekten in der SMS-Kommunikation, Networx 22, <http://www.mediensprache.net/de/networx/docs/networx-22.aspx> (16.12.2016).

Schnitzer, Caroline-Victoria (2012), Linguistische Aspekte der Kommunikation in den neueren elektronischen Medien: SMS – E-Mail – Facebook, PhD thesis, LMU München, <http://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/14779> (16.12.2016).

Söll, Ludwig (31985 [1974]), Gesprochenes und geschriebenes Französisch, Berlin, Schmidt.

Spelz, Tobias (2009), Kommunikation in den neuen Medien – Französische und brasilianische Webchats, Berlin, Frank & Timme.

Sperber, Dan/Wilson, Deirdre (21995), Relevance. Communication and Cognition, Oxford, Blackwell.

Stähli, Adrian/Dürscheid, Christa/Béguelin, Marie-José (edd.) (2011), SMS-Kommunikation in der Schweiz: Sprach- und Varietätengebrauch, Linguistik Online 48:4, <http://www.linguistik-online.de/48_11> (16.12.2016).

Stark, Elisabeth/Ueberwasser, Simone/Ruef, Beni (2009–2014), Swiss SMS Corpus sms4science, University of Zurich, <https://sms.linguistik.uzh.ch> (16.12.2016).

Storrer, Angelika (2010), Über die Auswirkungen des Internets auf unsere Sprache, in: Hubert Burda et al. (edd.), 2020 – Gedanken zur Zukunft des Internets, Essen, Klartext, 219–224.

Storrer, Angelika (2013), Sprachstil und Sprachvariation in sozialen Netzwerken, in: Barbara Frank-Job/Alexander Mehler/Tilmann Sutter (edd.), Die Dynamik sozialer und sprachlicher Netzwerke. Konzepte, Methoden und empirische Untersuchungen an Beispielen des WWW, Wiesbaden, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 331–366.

Storrer, Angelika/Beißwenger, Michael (2002–2008), Dortmunder Chat-Korpus, <http://www.chatkorpus.tu-dortmund.de> (16.12.2016).

Tagg, Caroline (2009), A corpus linguistics study of SMS text messaging, PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, <http://etheses.bham.ac.uk/253/1/Tagg09PhD.pdf> (16.12.2016).

Tagg, Caroline/Mason, Oliver (2011), Orthographic creativity in Twitter: tweeting about the World Cup 2010, Abstract for the Corpus Linguistics Conference 2011, <http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/college-artslaw/corpus/conference-archives/2011/abs-218.pdf> (16.12.2016).

Thaler, Verena (2003), Chat-Kommunikation im Spannungsfeld zwischen Oralität und Literalität, Berlin, VWF.

Thaler, Verena (2012), Sprachliche Höflichkeit in computervermittelter Kommunikation, Tübingen, Stauffenburg.

Thurlow, Crispin (2003), Generation txt? The sociolinguistics of young people’s text-messaging, Discourse analysis online 1, <http://extra.shu.ac.uk/daol/articles/v1/n1/a3/thurlow2002003-01.html> (16.12.2016).

Thurlow, Crispin/Poff, Michele (2013), Text messaging, in: Susan C. Herring/Dieter Stein/Tuija Virtanen (edd.), Handbook of the Pragmatics of Computer-Mediated Communication, Berlin/Boston, de Gruyter, 163–190.

Yates, Simeon (1996), Oral and written linguistic aspects of computer conferencing: A corpus-based study, in: Susan C. Herring (ed.), Computer-mediated communication: Linguistic, social and cross-cultural perspectives, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, Benjamins, 29–46.

Yus, Francisco (2001), Ciberpragmática. El uso del lenguaje en Internet, Barcelona, Ariel.

Yus, Francisco (2010), Ciberpragmática 2.0: nuevos usos del lenguaje en Internet, Barcelona, Ariel.

Ziegler, Arne/Dürscheid, Christa (edd.) (22007 [2002]), Kommunikationsform E-Mail, Tübingen, Stauffenburg.

Zitzen, Michaela (2004), Topic Shift Markers in asynchronous and synchronous Computer-mediated Communication (CMC), PhD thesis, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, <http://docserv.uni-duesseldorf.de/servlets/DocumentServlet?id=2771> (16.12.2016).