![]()

CHAPTER 14

![]()

Toolkit for Emerging Managers and Difficult Fundraises

Some fundraises are inherently more difficult than others. Despite your best efforts in planning, execution, and resource allocation, sometimes fundraises require more work than expected or are beleaguered by headwinds that make success difficult. Others become difficult due to missteps in fundraising. Difficult fundraises may include those from emerging managers, first-time funds, country-specific funds from developing nations, a niche strategy with limited investor appeal, and a strategy that does not neatly fit into the asset class buckets as defined by institutional investors, among other issues. In this chapter, we present solutions that would raise the likelihood of success while reducing the fundraising burden.

EMERGING MANAGERS

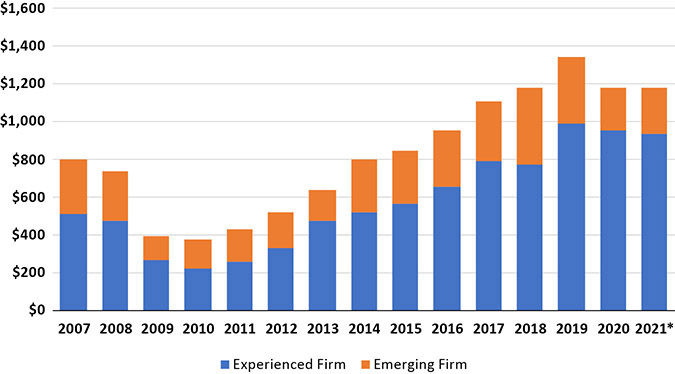

Fundraising for emerging managers has always been more difficult than for established managers (see Figure 14.1). In 2020,1 emerging managers received only 21 percent of total capital commitments to private equity managers, even if they made up 52 percent of funds. Moreover, 42 percent of the funds raised less than $100 million but the slice for emerging managers was only 2.4 percent of the total capital raised.

FIGURE 14.1 Private capital raised ($B) by manager experience

Source: PitchBook Data, Inc.

Emerging managers find it difficult to raise funds for several reasons. It takes time for an investor to get comfortable with a manager—to understand the strategy, get familiar with the investment philosophy, conduct due diligence—and align on such mundane issues as finding time to meet. This should be no different than what an investor is expected to do for established managers but who come with some credibility and brand recognition, which a new manager lacks.

Emerging managers also do not have the track record, established team, or processes that investors can rely on to more quickly earn their confidence. There is investor reluctance, due to possible continuity issues of first-time funds—an inability to maintain a team or raise enough capital to fund operations—even when performance is not an issue. Reliable data on the percent of first-time funds that never come back to market with a successor fund has been elusive, but anecdotally there are sufficient numbers to warrant attention. An investor who has invested the time to conduct research, do due diligence, and build a relationship with a manager will be averse to reinvesting the same amount of effort with a new manager. Emerging managers also can be naïve about high investor expectations when it comes to operations and investor relations. This could be another source of friction for investors that managers should take steps to avoid.

Investor apprehension with emerging managers reflects doubts about their ability to attract enough capital to make the fund viable. No early investor wants to jump into a fund only for the manager to decide to close shop due to capital-raising issues.

So why should investors bother with emerging managers? Empirical evidence shows that first-time funds outperform established funds by a margin of plus 6 percent annually.2 This is due to multiple beneficial characteristics of emerging or first-time managers—including better investment choices given limited capital to deploy, concentration in less-efficient market segments or securities, not having to manage underperforming assets from previous investments, a management team heavily reliant on superior performance for their compensation, and rationing risk allocation appropriately. Emerging managers and smaller funds tend to outperform larger funds, and that makes them attractive to investors, despite having other challenges. Those very issues do impose a higher fundraising toll on smaller, emerging funds.

In some cases, there are mitigating factors that make the fundraise easier, relatively speaking. This includes a well-established track record, such as in the case of spin-offs from established funds, first-time managers who had been managing portfolios (HFs), or senior investment professionals who can find reasonable attribution of their involvement and value addition to a portfolio. In any case, it is dependent on the previous employer or firm to allow a first-time manager to use track record to attract capital. Should such an arrangement exist, it would also imply explicit or tacit support of the manager by the larger established fund manager, which provides shadow branding and credibility to an emerging manager. While it is impractical to expect such arrangements to be common—after all, the new manager might emerge as a challenger to the established manager—it is possible to construct a track record that finds acceptability among prospective investors.

To do so, collate information from public sources to avoid confidentiality and proprietary information issues. Another option is to get corroboration from “those in the know,” including company management, service providers, and others involved in the deal. A third possibility, more acceptable to investors, is to have a dispassionate third party, such as an accounting firm, confirm the claims made in the track record. The industry relies on the norm, “Trust, but verify.” Such verification requires considerable investment of time, resources, and goodwill; third-party verification eases the effort and shares the information to all interested parties, moving the ball closer to the goal post.

Last, there is the question of whether the track record is replicable. Success achieved under vastly different conditions at an established firm may not necessarily be possible with a different team. In addition, a lack of supervision, absence of prior relationships, new back-office support, fundraising demands, the need to manage cash flow and other entrepreneurial demands can now crop up as an independent firm. Some solutions include outsourcing infrastructure, partnering with a fund platform that takes care of operations and creates a link to established relationships with providers, finding a seed investor who invests capital to fund the operations for a period of time in return for a stake in the fund or firm, and providing referrals from credible sources regarding the ability of the first-time or emerging manager to deliver results.

Recommended Solutions

Emerging managers should start with the right expectations for a fundraise. It will take longer and be more resource-intensive than you expected. Without properly planning for these two factors, you will be tempted to fight, micromanage, and be disappointed—all of which lead to bad outcomes. No matter how stellar you think a manager’s past experience is, it is up to the investor to buy into that claim. Going into a battle without the necessary tools (your track record and evidence of your investment acumen) will lead to undesirable outcomes. While investors understand that track records will be difficult to obtain for first-time managers, you must still find a solution. Do not hide behind the excuse, “My track record is the proprietary information of my previous employer” and expect investors to accept it. Provide as much concrete evidence as possible, even if that means triangulating and recreating the track record from public information and verifiable sources. The exactness matters less than directional—but believable—evidence.

Build strong relationships with the people you work with, so they will champion your efforts even after they leave the firm. At the least, ensure you have not burned bridges with any of them. You can be sure that prospective investors will call them to confirm your claims and track record. Their endorsement can be potentially valuable.

Do not overhype a short track record. This causes potential investors to view everything you present with skepticism and discount your genuine claims. Instead, emphasize processes, consistency of results and repeatability, or reasons for sustainable advantages.

Build your brand. There are many ways to do so—write articles for reputable publications, get speaking engagements, cultivate a social media presence, and develop whitepapers that show thought leadership. Carefully recruit a board of advisors and directors who can help not only open some doors for you but also give your image more credibility from the brands they have already built.

You should invest in a world-class team and a robust infrastructure for operations. If necessary, raise capital to fund the operations of the fund management company before raising capital for your fund. The goal is to remove the points of concern for potential investors. Some can be easily addressed—such as the need to build necessary infrastructure to fully execute and deliver the intended strategy. Investor relations experience—before, during, and after the fundraise—will create a brand for you as much as your performance does. Good investor relations will let your investors give you a chance to prove yourself in tough times.

One common mistake emerging managers make is looking at required documentation as a burden, rather than an opportunity to provide a compelling reason for the investor to invest. Private placement memorandums (PPMs) handled in a perfunctory, “let’s get this over with” attitude are less impactful than ones that tell the complete story and does justice to the main characters and plotline—the manager, investment philosophy, strategy, operations, governance, and risk management. PPMs should not just be a list of what needs to be disclosed, but also answer the who, why, how, and what-ifs. It should make a compelling case as to why the investor should consider you for an allocation.

Invest the time and resources to find an anchor investor or seed investor. First-time managers are understandably reluctant to part with a share of the economics, and they are hesitant to invest time, scarce resources, and efforts into a difficult task. However, the ability to secure the backing of a large investor with the necessary economic muscle to back you for the long term, assuming performance meets expectations, will alleviate concerns of other managers about fund viability and reinvestment risk. They can provide you the brand behind the brand.

You can seek emerging manager programs at institutions. Investors tend to follow a leader, such as a respected institutional investor, when the risk is significant. Capital commitment from a recognizable name is a catalyst that can change the direction of the fundraise, but the probability of landing an institution is fairly small for most first-time and emerging managers. That probability increases by targeting programs geared toward accepting emerging managers. Capital from such institutions as well as the learnings from the ensuing due diligence process will be valuable for courting other institutions.

Last, do not forget to focus on the deal pipeline. Investors are going to question you on upcoming deals and your ability to source value-added opportunities for the fund. On the other hand, closing on deals during the fundraise will create strong momentum for the fund. Some LPs have pools of capital dedicated just for the “pregnant primary”, i.e., GPs who are typically over 25% invested during the fundraise.

FUND SIZE ISSUES

Emerging managers need patience and good judgment when deciding on the size of successor funds (for private-equity-structured vehicles) or when seeking additional capital for existing funds (for hedge fund vehicles). This is true for all fund managers, but especially so for managers from emerging markets who have multiple thresholds to cross to secure an allocation. Most managers are eager to grow fast and want to rapidly increase the size of their AUM without adequate consideration of market demands and expectations. They may not be able to increase the fund’s return if the AUM gets too big, too fast.

This could go against expectations from investors that private equity managers can handle larger investment checks required for bigger funds and have capability to add value to larger portfolio companies at different stages of maturity. Similarly, hedge fund managers also worry about the market impact of large investments and increased illiquidity of a security as their holding size increases in relation to the float available. Investors are, for well-established reasons, reluctant to support larger funds that on average generate a lower investment return compared to smaller funds, ceteris paribus.

Humans are prone to a higher self-assessment of their own performance. Managers are no different when assessing the performance of their funds versus similar funds and other fund managers. In addition, they have an inflated estimate of the need for their strategy in an investor’s portfolio allocation. All these can lead to emerging managers being aggressive in shooting for a larger fund or a larger successor fund than what the market would reasonably support. Further, they err by being in the market too early—before there is enough evidence to convince prospective and current investors that the manager is ready to jump to the next level. Of course, there is the lure of larger management fees the manager can collect with a bigger fund.

In some cases, the focus on larger funds does stem from a personal goal of, say, wanting to manage more than $1 billion AUM, having a competitive streak, or searching for validation of their achievement (“my fund is in the same league as the globally recognized funds”). However, these managers must be measured and purposeful in deciding fund size and capacity for long-term success.

There are legitimate reasons for pursuing a larger fund size. In public markets, if there is higher liquidity due to a systemic change (such as regulatory changes in emerging markets that increases the free float), raising individual check sizes can be justified. Another reason could be to avoid co-investments or syndication that sustained previous funds and increased stakes in portfolio companies. There could be a case where larger investments of the manager substantially outperformed smaller investments, and there are identifiable reasons why the larger investment worked relative to the smaller ones. One cannot presume to know all the reasons why a fund size or strategy capacity could be markedly larger; it is important to ensure that reasons presented would be convincing to prospective and current investors. It is not uncommon for some investors to start paring down allocation as the strategy AUM increases, while others wait for the fund to grow larger before they make an allocation.

In addition, as the size increases, the resources available need to be in line with investor expectations. As an example, a larger fund that is allocating to more companies or taking larger stakes that entail more board positions than previously should have the necessary resources to fulfil those obligations faithfully. A hedge fund investing larger checks would have to ensure there are adequate trading resources to ensure minimal market impact.

Investors will invariably ask a first-time GP about future growth expectations and the size of future funds. The GP must be prepared with a thoughtful response. Some managers answer this question by focusing on mapping fund size to check size and the size of teams that can support a deal. For example, on a $1 billion fund, you could have $100 million checks and 10 deals per fund, plus four investment team professionals per deal (a partner, two vice presidents, and another executive).

Should the fundraise fall short of expectations or take too long to complete, one risk is investor skepticism as to why others were not committing to the fund. Managers who have been thoughtful about rightsizing their fund, where there is capital large enough to faithfully execute the strategy, but small enough to maintain a supply gap creates a fear of missing out (FOMO) effect for future funds. It is a great strategy. So it is with hedge funds that have been closed to new capital for a long time only to see the flood gates open when market conditions prompt an increase in capital that can be put to work effectively. Such was the case with some of the largest hedge funds during 2008, which had previously been closed to new capital and encountered overwhelming demand when they reopened during the 2008 financial crisis, as the market fell precipitously.

Unfortunately, this is not the case for many emerging market PE funds, which typically take a longer time to gain traction and fall short of fundraising goals due to their aggressive and unrealistic AUM target. This in turn results in difficulty raising future funds.

One reason for failing to meet fundraising targets is that a strategy or region is too narrowly defined, so investment opportunities are very limited. A manager may be tempted to look for opportunities elsewhere, but there will be consequences for such strategy or geographical drift. If there is a strategy drift, managers should be prepared to explain to and convince investors that the shift was warranted. For example, a regulatory change that restricted the ownership stake in a company could justify the strategy change, because it pushed the fund to increase the number of investments.

Some Recommended Solutions

Rightsizing the fund is a matter of skill, market awareness, judgment, and discipline. Eagerness to grow rapidly might prove detrimental to the manager if not handled well. For hedge funds, there is not a set limit and timeline to meet fundraising goals, unlike private equity. Such private equity time constraints may force the manager to make suboptimal decisions if the pace of the fundraise is in danger of missing the AUM target.

Survey the market. Ask advisors, consultants, LPACs, and potential investors for input about the intended size of the fund. Be willing to push for a higher AUM, but only after understanding the costs and impact on this and future fundraises.

Hedge funds are not immune to size issues. If they become too large for their strategy, investors would see it as an asset grab and redeem at the earliest viable opportunity. The manager may be able to stave that off through superior performance, but it is not uncommon for sophisticated investors to pare down exposure to the manager as AUM increases, even if performance aligns with expectations.

Go to market with a new fund only after the previous fund is nearly fully invested—and the manager has bandwidth to handle it and there is an investor need to diversify across vintages. However, if there is a perceived rush to invest in anticipation of a successor fund, current investors will be disaffected, and prospects will need reassurance. Managers should be transparent about the pace of investing and earn the confidence of current investors, which can be demonstrated by returning capital. The fundraise for a future fund will get off to a flying start only when current investors support it and the re-up rate is strong. Otherwise, it becomes a needless exercise that hampers future fundraises.

It is unwise for emerging managers to rush the launch of another fund without adequate exits, unless there is overwhelming evidence that the portfolio is bound to deliver blockbuster results at the exit, or there is tremendous investor support to launch a new fund for a multitude of other reasons. These include market conditions opening up an opportunity that might disappear if the fund launch is delayed.

INHERENT CONFLICTS: MULTIPRODUCT MANAGERS OR SPONSORED FUNDS

Multiproduct managers are those that handle competing or complementary funds with the same investment ideas, internal and external resources, and oversight. (Successor funds and private equity funds at different stages of their life cycle are excluded in this discussion.) Prospective investors are suspicious of managers that invest simultaneously through multiple funds, believing they are more interested in asset gathering than generating the best performance.

There are also questions about inherent conflicts of interest in allocation of time and investment opportunities among the multiple funds they manage. One concern is that when a fund is falling behind, the manager would focus on the better-performing funds instead of fixing the laggard. Some institutions have unwritten policies against using multifund managers or insist on applying additional scrutiny.

Sponsored funds are those backed by a broader organization such as a bank, asset manager, government, corporation, or other entity that join the investment management process as an investor, service provider, regulator, or market participant. These funds can be perceived as self-dealing, with issues of governance and loyalty that can deter investors. In some cases, the perceived conflict is real, as in the case of bank-sponsored funds that may be obligated to use their backers’ advisory, brokerage, corporate banking, and investment banking services. These funds might have gotten a better deal, with a higher level of service, elsewhere.

The fund might also be barred from investing in opportunities involving the sponsor’s competitors. With such hurdles, why would the sponsor and investment team even start the fund? The fund team wants to benefit from the broader resources of the sponsor. In turn, the sponsor wants to buy the skills and expertise of the fund team, or they want to partner with the fund team to take advantage of market opportunities that they otherwise could not, due to regulatory or operational constraints. Sponsors also see the value of cross-selling the fund to existing clients, which diversifies revenues and risks while growing the overall size of the business.

ADDRESSING THE CONCERN OF INVESTORS

Multiproduct Managers

Multiproduct managers need to convince investors that each product is adequately staffed and has sufficient resources to succeed with the necessary operational and supervisory oversight. In addition, they should also delineate the guardrails under which they will operate and ensure investor interests are protected. Multiproduct firms are more stable, as they can rely on the diversification of revenues and risk to tide over challenging times, have deeper pockets to attract and retain talent, promote cross-product learnings, benefit from scale economics, strengthen relationships with outside service providers and counterparties, and leverage a common operating platform that reduces costs.

This needs to be demonstrated and substantiated. Yet, there is a corner of the market that simply does not play in this sandbox. It is for the manager to figure out who does not want to participate and to fish in a different part of the ocean to remain efficient and productive during fundraising. It is not in the best interest of the manager to try to change minds; it is more productive to find investors who share your thinking, see value in what you offer, and are willing to back your strategy.

For those who are interested but have concerns about product focus, one course of action is to lead investors through periods of difficulty in one or more funds when others were performing well and show how there was corrective action taken and additional resources allocated to the fund to ensure performance improvement. Show evidence of your actions, not just your intentions.

When dealing with multiple products, some funds will be significantly larger than others; they could even be orders of magnitude bigger. Managers need to enforce mechanisms to ensure each product gets equal priority. This could come through incentive structures for the team, priority terms, or other structural constructs. Consciously avoid structuring funds and fund terms in a manner that pits one strategy against others. Ultimately, it comes to trade-offs for both the manager and the investor. Investors need to ensure their investment is handled and executed according to their expectations. It is the manager’s job to convince them of such an outcome.

Sponsored Funds

Sponsors need to use necessary controls to ensure internal dealings are compliant with not only the governing regulations but also with a fiduciary standard. The easiest and most acceptable solution is not to engage in internal dealings at all, such as transactions with the sponsoring parent and its affiliates. However, there could be occasions when these transactions are necessary. If so, these activities should be completely disclosed, and the sponsor should provide a written policy that not only talks about the process to be followed, but also the reasons for such decisions and the assurance that no transaction will be made that would be detrimental to investors.

The sponsoring entity can add value to the fund by mere association. For example, an Asian fund sponsored by a large private equity fund in the United States will benefit from the processes, IP, network, relationships, investor base, and experience of the sponsoring entity. This would help the fund and its portfolio companies to do better than if they were to go on their own. However, if the only contribution of the sponsoring entity is marketing acumen, it leads to questions of whether the relationship will last long term once the local team has built its own brand and can raise its own capital. The investing team would not want to unnecessarily give up economics to sponsors—something most investors also support to ensure a stable and sustainable team with very little disenchantment with the sponsor.

Over time, the sponsor and the local team may split up. There are many reasons why, and much of it is centered around control, value addition, and share of economics. A good example is the relationship between Westbridge Capital and Sequoia, the global venture capital firm.3 Westbridge merged with Sequoia in 2006 after it had already raised and invested two funds. The merged entity, Sequoia India, raised five funds and rapidly scaled up both AUM and the team. However, six years after the merger, the original Westbridge team left Sequoia India to restart Westbridge Capital, this time to focus primarily on public market investing. Sequoia India continues to operate without the partners who left.

Governance of the fund could also become an issue. Does the sponsoring entity exert undue control over the fund that in turn relegates the interests of other investors? Managers need to ensure policies and procedures are not only fair but also provide for other investors to have reasonable oversight as they steward their allocation with the manager.

FUNDRAISING AMID MANAGEMENT CHANGE, SUCCESSION, OR OTHER TRANSITIONS

Fundraising during a transition, planned or unplanned among senior members of the team, can be a real challenge for most marketers, for good reason. That is why cordial and mutually acceptable transitions at most funds happen after the fundraise, with succession discussions occurring beforehand. Investors are not just underwriting the strategy, but also expect the team to faithfully execute the strategy and sustain the firm’s accomplishments. When there is a change in the team, especially at the senior levels, questions about stability, continuity, and ability will arise—all of which can be serious obstacles for a fundraise. These hurdles decelerate momentum, invite skepticism and scrutiny, lengthen the process, and raise costs.

As the alternatives industry continues to mature, succession plans are becoming increasingly important especially as leadership at asset management firms enter their twilight years. Firms must communicate their succession plans with clarity and confidence prior to and during the fundraise, and they must do so as early as possible.

Focus on Development

Succession is not just about transitions occurring over a year or two; it is about strong development of the next generation of leaders throughout a firm, development of a strong culture based upon ownership, and equitable sharing of economics broadly across market cycles. This is a long-term game with effective transitions taking place over the life of multiple funds, and these plans are an important aspect of the success of any firm.

Start Early

In the years leading up to a fundraise where planned succession might take place, the partnership must map out the terms of succession over multiple funds with respective legal counsel in a formal memorandum of understanding (MOU) or legal document. You cannot go into a fundraise with any ambiguity. LPs will speak directly with you about it during their onsite due diligence sessions and will ask for clarity on the topic in RFPs and DDQs. Fund managers push CEOs of their respective portfolio companies to have clear succession plans in place, but many times do not focus on their own firm’s succession plans.

Communicate Clarity of Terms

With the support of trained legal counsel, succession management must be clearly mapped out around the terms of ownership, management, and governance and communicated to the broad LP community and internally within the firm. At one private equity firm where the cofounders were well beyond retirement age, the succession terms around economics and governance among the executive team and cofounders for the next two funds were succinctly mapped out in one simple slide in the investor presentation for surprised LPs to see. This refreshingly transparent slide resonated well with LPs who were initially concerned about succession, but now could clearly see metrics around ownership, carry, and governance (number of seats on board, IC, and compensation committees) for the upcoming and then subsequent fund. They could see key decisions were to be made by the majority of votes, with appropriate minority protections, and how the CEO was responsible for day-to-day operational activities and when governance rights would cease for the founders.

Manage the Future and Control the Unexpected

Change and transition can be difficult. Retiring leaders often have their identity centered around their firms. Many have their names on the door and have built up their businesses over many decades. For them it can be hard to let go, even for these illustrious and dynamic leaders fast approaching retirement. Egos, personalities, and economics have strong influences on seamless succession and the unexpected can happen. In one case, despite mapping out succession, the founders nevertheless could not let go, exercised a loophole in the MOU, and the partnership fell apart a few weeks before the first close on a major fundraise—with the new executive leadership departing the firm.

CONCLUSION

Every fundraise is challenging in its own way. However, when some situations make it particularly difficult to fundraise, trying to figure out solutions in the middle of a frantic period is not practical. In most cases, lack of self-assessment to prepare for potential investor questions and concerns leads to unfavorable outcomes. Most marketers and fund managers who have successfully traversed difficult fundraising terrain often prepare themselves for the challenge much like a marathoner conditions themselves for a long race. Elements of the toolkit in this chapter can be an ideal starting point for managers and marketers to structure their response to their own situation to improve their chances for success. However, the implementation of any plan is dependent on organizational and investor buy-in. Fund managers would see positive outcomes when the communication effort is in line with the situation being addressed.