16

FOUR TESTS TO RUN BEFORE FUNDING

Many non-marketing executives’ first glimpse of marketing plans, particularly promotional plans, is when the budget is being prepared for approval. CFOs and financial managers, in particular, often have limited involvement in the planning process. Yet, they are asked to evaluate whether the marketing department or executive team’s proposal is a good financial investment for the company. At the same time, when marketing efforts fail, the CFO and the financial management team is most likely to see and feel the fallout as the company scrambles to address missed revenue targets and unanticipated expenses.

Regardless of your level of involvement in developing plans for the marketing function, there are four tests you can run to help you determine whether the proposed marketing investments are solid investments for your company: the Alignment Test, the Assignment Test, the Risk Assessment Test and the Anticipated Returns Test.

This chapter reviews each of these tests and illustrates their use with very simplified case studies.

THE ALIGNMENT TEST

The Alignment Test provides a means of evaluating how well the plan is aligned with business and financial objectives. Plans that satisfactorily pass this test are more likely to succeed for two reasons. First, if the executive and marketing teams can both walk through the plan and explain the connection between the marketing tactics they have selected, the marketing strategies they are pursuing, the impact these investments are likely to have on the influencing factors and how these activities will ultimately affect business and financial outcomes, the plan is more likely to be consistent with, and supportive of, the company’s overall strategy. If the plan fails this test, it can be an indicator that the plan was developed without sufficient executive input or support or that the team identifying tactics did not clearly understand the objectives.

Second, when executives clearly understand how and why investments are being made and how they work together to achieve business objectives, they are less likely to second guess the planning process or discontinue funding before the objectives are achieved. This test helps ensure that the marketing and executive teams are in agreement on the plan before the plan is executed, improving the odds that it will be completed successfully.

How the Test Works

This test follows the flow of the Marketing Alignment Map introduced in chapter 4, ‘Evaluating Marketing Plan Alignment.’ However, it approaches it in a different order. The objective is to ensure each key member of the marketing and executive team can explain why the company is engaging in specific marketing activities, like a coupon campaign or a new distribution channel, and what the outcome will be on the market and the business as a result. This test can be performed at the company level, division level or an individual investment level. At each step, all parties should understand and be in agreement with the actions.

To facilitate this exercise, I recommend using a chart similar to box 16-1 that follows:

Step 1. Participants should be able to specifically describe the marketing tactics or activities in which the organisation will be investing and the way in which the company will know that it has been satisfactorily completed. This helps prevent vague tactical objectives and improves accountability.

For examples of these, return to chapters 7-10, which cover the most common categories of marketing tactics (products/services, pricing approaches, distribution approaches and promotions) and common tactical measurements.

Step 2. Participants should then be able to link each marketing tactic to the marketing strategy or strategies to which it is connected and describe how the tactics will help the organisation fulfil the strategy’s objective. The tactics should make sense given what the executive or manager knows about the target market’s purchasing decision process and demographics. Like the marketing tactics, the strategies should have clearly articulated metrics associated with them. This ensures that the tactics are based on broader marketing strategies and weren’t created as ‘one off’ activities.

Additional guidance on confirming a fit between the marketing tactics, marketing strategies and market demographics are included in chapter 6, ‘Aligning Marketing Tactics With Influencing Factors.’

Step 3. Each strategy should, in turn, be clearly tied to one or more influencing factors, the purchasing decision criteria that the marketing initiatives are designed to address. This helps ensure that the marketing strategies have been developed and the tactics selected with the company’s own market in mind, rather than as mirrors of other players in the market or in an unfocused effort to increase brand awareness. The management team should be confident that if the company pursues the marketing strategies identified, they will have the desired impact on the influencing factor.

Additional information about this step is the subject of chapter 5, ‘Understanding What Influences Market Behaviour.’

Step 4. Next, participants should also be able to describe the combined impact the tactics supporting a marketing strategy will have on the influencing factor(s), described in terms of expected marketing outcomes. Expected marketing outcomes should be stated in the same terms as both the organisational objectives and the expected financial returns. This provides an opportunity for questions regarding expected financial outcomes, timing of results and related expenses.

This is part of the return on investment (ROI) estimation process outlined in chapter 11, ‘Evaluating Returns on Marketing Investments.’

Step 5. Finally, participants should be able to describe how the business and financial outcomes of the plan dovetail with the company’s business and financial goals. This confirms that the company is prioritising correctly based on the factors most likely to affect its success. If the sum of the impact of all marketing strategies is insufficient to meet the organisational and financial objectives of the organisation, either the business and financial objectives or the marketing plan must be adjusted.

Box 16-1: Sample Alignment Test Chart

|

DO THESE … |

TIE TO THESE …? |

Step 1: |

Marketing Tactics: Specific activities the company will take |

Expected Tactical Outcomes: metrics and related outcomes used to evaluate success |

Identify the primary marketing tactics the company will pursue … |

… and the metrics that will be used to determine whether they were successfully completed, along with the measurement processes and systems required to track success. |

|

Step 2: |

Marketing Tactics and Expected Tactical Outcomes |

Marketing Strategies and Objectives: The approaches the company will take to favourably affect the factors that influence the customer’s purchasing decision criteria, stated with measurable objectives. |

Verify that the marketing tactics and expected outcomes … |

… support the marketing strategies, are appropriate choices for the targeted markets and together will deliver the impact expected of the marketing strategy. |

|

Step 3: |

Marketing Strategies and Objectives |

Influencing Factor: Aspects of the customer’s purchasing decision process that support or impede the company’s ability to sell to the market. |

Assess whether the marketing strategies and objectives related to a given influencing factor … |

… will have the expected impact on the influencing factor. |

|

Step 4: |

Influencing Factor and Marketing Strategies |

Anticipated Business Outcomes and Financial Returns: The measurable outcomes relative to business goals and the financial returns the company expects from its marketing efforts. |

Review the impact a change in the influencing factors … |

… will have on business and financial results of the company. |

|

Step 5: |

Anticipated Business Outcomes and Financial Returns |

Performance Expectations: The company’s targeted performance levels |

Verify that the anticipated impact the marketing programme will have on the company’s business and financial performance … |

… meets company expectations and merits the investment. |

Case Study: The Alignment Test in Action

The subject of this case study is a proposed marketing investment within a mid-sized services company that provides health management services to large companies as a way to lower their client’s overall health insurance costs. They are under the leadership of a new CEO, who has commissioned market research to get a better understanding of the factors impeding corporate growth. The research suggests that the market is interested in improving employees’ health through proactive management because it will lower health care costs, but there are a number of barriers.

First, the link between the company’s services and health outcomes is not clear to prospective customers. Second, many companies use alternative approaches, such as funding gym memberships. Finally, the company’s name and the services it offers are not well known beyond its own clients. The research also identified the likely decision-makers for services and other influencers within the organisations whose opinions could sway the decision. Further, the research suggests that if the health management services company can increase awareness of their organisation and the benefits of their services by 40%, they are likely to increase their gross margins by 120% over three years.

The new CEO, with the enthusiastic support of the marketing team, proposed that the organisation invest in its first advertising campaign in order to increase awareness. The associated budget line item was significant to the company, and the CFO was concerned. Most of the company’s previous sales had been made by a sales team that had relationships with the decision-makers within their client organisation. To help allay his concerns—or identify issues he can bring to the leadership team—the CFO decided to walk through the Alignment Test, as depicted in the boxes that follow.

The proposed marketing tactic is a significant advertising campaign, using broadcast and print media. The tactical objectives the marketing team has outlined in the proposed plan are fairly clear. They identified the specific media they want to use and the number of impressions they want to have. They have a timeline for execution and know how many commercials and advertisements they want to run before the end of the fiscal year.

|

DO THESE … |

TIE TO THESE …? |

CONCLUSION |

Step 1: |

Marketing Tactics |

Expected Tactical Outcomes |

The tactic is very specific and has clear and measurable completion and intermediate metrics. |

Advertising campaign, print and broadcast, positioning the company as a leading provider of business-to-business employee health management solutions. |

Completion Metrics: Three flights of six ads in business journals within the geographic service area over 18 months; one ad running on local broadcast television over two, three-month periods. Intermediate Marketing Metrics: X impressions within decisionmaker populations. |

The tactics also seem to align with the marketing strategies the marketing team had identified, based on the market research. Increasing visibility among decision-makers is a key strategy, and the advertising campaign’s objective is to increase awareness. The local business journals and the broadcast stations were selected based on the media identified in the market research.

|

DO THESE … |

TIE TO THESE …? |

CONCLUSION |

Step 2: |

Marketing Tactics and Expected Tactical Outcomes |

Marketing Strategies and Objectives |

The broadcast media is too broad and would waste funds. The business journals are probably more appropriate. This tactic alone will not make the desired impact. |

Advertising campaign on local broadcast television and business journals. Media sources were selected based on research. |

40% increase in recognition of company name and services among decision-makers. |

The research indicated that the target market uses both of these media for information. However, the market is relatively small, with a target client population of 450 companies and less than 2,000 relevant decision-makers. After further discussion about the feasibility of this audience, the management team decides that the broadcast advertising is too broad an approach to make sense. Although it might reach the decision-makers, it would also ‘waste’ messaging on thousands of individuals outside their target market. They conclude that the business journal advertising alone would be insufficient to meet their strategic objective.

As a result, they ask the marketing team to revisit the research and the plan. A more careful evaluation of the client’s decision-making criteria, mapped out through the research, suggests that a referral from a peer would be more influential than simply increasing name recognition. This leads the team to add a referral programme to the marketing mix, shaped by data from the survey. When the management team reviewed the revised plan, the results looked more favourable.

|

|

TIE TO THESE …? |

CONCLUSION |

Step 1: |

Marketing Tactics |

Expected Tactical Outcomes |

The tactics are very specific and have clear and measurable completion and intermediate metrics. |

Print advertising campaign and intermediate metrics. positioning the company as a leading provider of business-to-business employee health management solutions. Referral campaign run among existing customer. |

Completion Metrics: Three flights of six ads in business journals within the geographic service area over 18 months. Intermediate Marketing Metrics: X impressions within decisionmaker populations. Y referrals within the first six months. |

|

|

Step 2: |

Marketing Tactics and Expected Tactical Outcomes |

Marketing Strategies and Objectives |

The revised tactics match market demographics and customer decisionmaking processes, and the management is confident they will have the desired impact. |

Advertising campaign in business journals. Referral campaign. |

40% increase in recognition of company name and services among decision-makers. |

Upon reviewing the revisedplan, the management team was confident that the combination of tactics would increase name recognition by 40%. The company moved to the next step in the Alignment Test. When the management team considers the alignment of the strategies with the purchasing decision process, they seem to be a strong fit.

|

DO THESE … |

TIE TO THESE …? |

CONCLUSION |

Step 3: |

Marketing Strategies and Objectives |

Influencing Factors |

Yes. Based on what the company knows about how the market makes decisions, the strategies make sense and will have an impact. |

40% increase in recognition of company name and services among decision-makers. |

Awareness that services are an option. Receiving a referral from a peer. |

Although the company has limited baseline information, the marketing team has made an informed assumption using the research about the impact that a change in the influencing factor could have on revenues. After much discussion, the CFO concurs. A 40% increase in the recognition of the company’s name and services could allow the company to increase revenues by 22% over the next two years. The company’s CEO was targeting a 20% increase in revenues.

|

DO THESE … |

TIE TO THESE …? |

CONCLUSION |

Step 4: |

Influencing Factor and Marketing Strategies |

Anticipated Business Outcomes & Financial Returns |

The risk-adjusted ROI seems solid, and the management team is confident that the anticipated change in customer perception will deliver the growth as indicated. |

40% increase in recognition of company name and services among decision-makers and increased referrals from peers. |

Expand existing services by 22%. 462% return on investment (ROI). |

||

Step 5: |

Anticipated Business Outcomes and Financial Returns |

Performance Expectations: The company’s targeted performance levels |

The anticipated business and financial returns meet the company’s performance expectations. |

Expand existing services by 22%. 462% ROI. |

Revenue growth of 20%. No investment with an anticipated ROI of less than 100%. |

Based on the Alignment Test, the CFO recommends that the management team approve the plan as revised.

THE ASSIGNMENT TEST

Even when a company’s marketing plan satisfies the Alignment Test, it can fail for other reasons. One of the most common is that the budgeting process took into consideration materials costs, including advertising buys and other promotions costs, research and development, hard costs associated with channel expansions and the impact of pricing approaches, but failed to consider the incremental time required to execute the plan. In some cases, aggressive new marketing plans pile additional work onto existing employees’ plates, increasing the chances of burnout or making it difficult to meet deadlines. In other cases, the budgeted costs do not accurately reflect the actual cost because the company must add additional staff, either internal or external, to support execution. These are the issues outlined in chapter 13, ‘Staffing the Marketing Department,’ regarding staffing the marketing function.

The Assignment Test helps avert failure in execution by ensuring that every activity has been allocated to a specific resource who has, in turn, accepted that responsibility.

When I am facilitating marketing plan development with middle-market companies, I generally complete the Assignment Test with them before presenting the results to the executive team. With small companies, the non-marketing executives with budget responsibility, including the CEO, chief operating officer (COO), CFO and others are often involved in the process itself. Although many executives suggest they simply skip this section, I recommend that they remain involved to ensure the assignment of responsibilities is realistic. In larger companies, this test can be delegated to the marketing team. The non-marketing executive should simply confirm that all additional workload, including oversight and coordination, have been assigned, and the assignments accepted prior to funding.

How the Test Works

Whether conducted by the executive team or delegated to the marketing team for completion, the nonmarketing executive should ensure that the time required for additional activities is budgeted and accepted by the individuals to whom it is assigned. To do so, use the following steps:

Step 1. First, review each marketing tactic identified within the plan, breaking it into the steps required for completion.

Step 2. Next, estimate the amount of time required to complete the activity. In many cases, we find marketing professionals are optimistic about the amount of hours that will be required. As a result, the budgeted time figures are quite low. If possible, time requirements should be estimated based on prior experience or the investment of time in similar projects.

Step 3. Once all the activities are outlined and the time required for each step has been estimated, make sure each activity has been assigned to an employee or group of employees for execution. During this step, look at any existing activities that have been removed from an employee’s workload. For example, if the marketing planning process identified existing activities that are not a fit to updated strategic objectives, and those programmes are eliminated, the employee should have available time.

The net number of hours assigned to the employee must be realistic, or the plan is unlikely to receive the attention required to make it a success. Also, the employee to which the tasks are assigned should have the requisite skill sets to complete the job effectively.

Step 4. Finally, confirm that every employee to whom a task has been assigned has accepted the additional workload and believes he or she can complete the task without negatively affecting other areas of his or her workload.

When I am facilitating marketing planning retreats, particularly with small and mid-sized companies, I use box 16-2 to facilitate the conversation.

Box 16-2: Sample Assignment Test Chart

STEP 1 |

STEP 2 |

STEP 3 |

STEP 4 |

|

Marketing Tactic This is the specific tactic, whether it is a new product introduction, a temporary pricing approach or a new promotional initiative. |

Specific Activities The activities that will be required to execute on the tactic. |

Hours and Skills Required The number of hours required by skill-set. |

Assignment The employee, or team of employees, to whom the task of completing the activity is assigned. |

Confirmation Y/N |

Case Study: The Assignment Test in Action

The CEO of a national professional service firm wants to conduct a performance audit of his firm’s marketing efforts—and then help the company update its marketing plan. Although the company has experienced steady growth, it hasn’t kept pace with market growth in many of its markets, and the managing partner feels that the marketing could be at fault.

After interviewing partners, clients and marketing team members and looking at the company’s marketing promotions, pricing structure and competitive environment, it becomes evident that the biggest barrier to growth was a channel problem. Clients select among equally qualified professional service providers, in a mature and very competitive market, based on relationships with the key service provider. In professional services, the professionals, whether they are CPAs, lawyers, architects, engineers or consultants, are the primary sales force for the company. In this case, its sales team is primarily responsive in nature. Because of this, its smaller and ‘hungrier’ competitors had begun to erode the possibility for additional growth through more aggressive business development efforts.

Based on this analysis, and working with a small team of marketers and partners, the CEO developed a new marketing plan for the company that included an increased focus on relationship development. The plan included training for its ‘sales force,’ the development of personal business development plans, updated collateral materials designed based on feedback from partners about their needs during business development calls as well as clients, client entertainment events, seminars and other elements. The plan satisfied the Alignment Test, and when the plan was presented to the partners, on whose plates the plan laid most of the responsibility for execution, it was heartily approved.

At first glance, it met the Assignment Test as well. After all, the partners, in a company-wide meeting of the partnership, had been presented with and eagerly supported the plan. However, the CEO wisely took one final step before considering the plan complete. He outlined how each office’s managing partner would hold the partners in their office accountable and was very specific about the time that would be required. Next, he asked each managing partner to take the outline of responsibilities to each partner in his or her office and request that he or she review and sign a form acknowledging that he or she could, and would, accept these responsibilities. If they would not sign, the managing partners were requested to ask what changes would be required in order to make the plan operational for each managing partner.

Although this effort was somewhat counter-cultural because the firm’s partners had traditionally operated largely independently, it paid off. About 10% of the partners signed off. This was roughly consistent with the company’s historical performance. The other 90% all had reasons that they wouldn’t or couldn’t participate, from workload, to their own perception of client relationships or their performance. Approved as it was designed, this plan would fail.

After several more months of work to address the concerns, the firm adjusted the plan, adding in some staffing changes, additional coaching on delegation and time management and including incentives for performance. When the plan was finally approved, most of the partners had signed off on the workload, and the expected outcomes had been adjusted to reflect the expected impact of those who might not carry through.

Although this problem is particularly common among professional service organisations of all sizes, it is also common in other business-to-business settings and with fund development plans for non-profit organisations. In the latter case, the plan usually includes some component of board engagement. When approved, the board is often enthusiastic about the outcomes, but the response of individual board members, when asked about the status of their personal commitments to raising money, is often ‘I didn’t think you meant me.’

THE RISK ASSESSMENT TEST

Many plans fail because individuals responsible for planning have made overly optimistic assumptions about outcomes. This has two negative impacts. First, it can encourage ineffective spending. Second, when the plan’s performance begins falling short of expectations because of poor assumptions, it increases the odds that the executive team will cut or eliminate funding of this plan and be more inclined to do so with future plans as well.

Assumptions are necessary in any planning process. However, they do represent risk. Too many assumptions mean that the expected outcomes are less certain. The Risk Assessment Test reviews the plan for assumptions and serves as a basis for adjusting estimated financial returns, making them more reliable for financial planning purposes.

How the Test Works

The marketing or planning team is typically the group that assesses assumptions and performs this test. However, the executive team should review the results and evaluate whether any key assumptions were missed. To complete both processes, use the following steps:

Step 1. First, the marketing or planning team should review each strategy within the plan and evaluate the assumptions made relative to potential risk. To do so, use the risk assessment decision tree introduced in chapter 11 and reproduced again here as figure 16-1.

Figure 16-1: Risk Assessment Decision Tree

By reviewing each assumption relative to the risk assessment decision tree, the team can evaluate where the plan contains significant risk and work to mitigate those risks through research before reviewing the plan with the executive team. Once the team agrees that there are no further adjustments to the assumptions, the plan or the anticipated ROI, the team is ready to present the plan to the executive team.

Step 2. When the executive team reviews the plan, they should ask team members to review with them the critical assumptions and describe any mitigating actions that have, or could be, taken. Critical assumptions include assumptions which, if incorrect, will cause the marketing strategy or tactic to fail or will result in substantial financial loss. To facilitate the discussion, the planning team might present a list of assumptions in a format similar to the one in box 16-3.

Box 16-3: Sample Critical Assumptions Chart

MARKETING STRATEGIES AND/OR TACTICS

CRITICAL ASSUMPTIONS

MITIGATING ACTIONS

This is the specific marketing strategy or tactic, whether it is a new product introduction, a temporary pricing approach or a new promotional initiative.

These are assumptions that are critical to the plan’s success and/or will cause substantial financial loss if incorrect.

These are the actions the team has taken to mitigate the risk. These could include testing through market research, reliance on historical performance or other data which lends credibility to the assumption.

Step 3. Using this information, the executive team can assess whether further adjustment of expected returns or anticipated impact are warranted or whether additional testing is required prior to plan approval.

Case Study: The Risk Assessment Test in Action

Chapter 11, which reviews the Measurement Myth, includes one example of the use of the risk assessment decision tree. To illustrate the process using another, consider a restaurant that is developing a new marketing plan. The owner, also the marketing director for the restaurant, is discussing the plan with the manager.

The owner has been chatting with guests as they come in for meals, asking them how they found out about the restaurant. If someone referred them, she asks for their name, so that she can thank them for the referral. When guests indicate that they have visited the restaurant before, she finds a way to ask what they particularly enjoyed. She has also tracked guests who return repeatedly and knows them by name.

As a result of these conversations, the owner had created an informal tally of results. She found that about 35% of her guests came in based on a recommendation from a friend who had dined there in the past. Another 40% lived in the neighbourhood and noticed the restaurant when they were running errands. The last 25% came in because of some promotional coupons she had distributed at farmers’ markets in the region. There were a few guests who referred more guests than anyone else. In addition, a few guests who initially came in because of the promotional coupons returned later without one.

Her restaurant was fairly new, and she had more capacity than she did money for marketing, so she knew that her plan would need to be thoughtfully constructed. Based on what she knew, she felt the key influencers of market behaviour were recommendations, visibility and discounts. However, individuals who came because of recommendations or visibility were more likely to return. Her estimate was that 50% of the individuals in that category eventually returned to the restaurant. By contrast, only about 20% of the promotional coupon recipients would return.

She decided on two primary marketing strategies. First, she decided to work on increasing recommendations by 35%. Second, she decided to maintain her focus on the local farmers’ market because it did seem to be producing some sampling behaviour. If that approach was successful, she would have enough returning business that she could eliminate the coupon programme, which was relatively expensive. This programme would, she decided, allow her to meet her growth goals.

To increase recommendations, she decided to begin offering a gift to individuals whose recommendations resulted in a new customer through the door. She planned to offer the programme to anyone who ate at the restaurant. To participate, they would sign up for the programme and when a guest gave their name as the referral source, she would e-mail them a coupon for a free dessert.

In the course of explaining the new recommendation programme, about which she was quite enthusiastic, the manager asked her about the possible drawbacks or risks associated with the plan. After careful considerations, she identified the following assumptions as shown in box 16-4.

Box 16-4: Restaurant Recommendation Programme Critical Assumptions

MARKETING STRATEGIES AND/OR TACTICS |

CRITICAL ASSUMPTIONS |

ELABORATION |

Increase recommendations through a rewards programme |

An incentive is required to prompt recommendations. Guests will participate in the programme. |

If recommendations happen without incentive, it is possible that adding a recommendation incentive will discourage guests who worry that friends might question their motives. If recommendations happen without a gift, adding a reward programme may simply be adding an expense without substantial benefit. Clearly, in order to be successful, guests must participate in the programme. Success will be measured by the number of new customers that report having tried the restaurant based on a recommendation. |

She considered the significance of each of these risks against the risk assessment decision tree, answering each question in turn:

Is this assumption critical to plan success? Yes. The owner decided both assumptions represented risk. The first assumption, that something free was required, was risky because if she was wrong, people who otherwise might have made recommendations would not, and the business would incur added expense with free gifts.

Is the investment expense high? Yes, for her nascent business, the expense of error would also be high.

Would the cost of verifying the assumptions make the ROI unattractive? She considered this for some time. Clearly, third-party research would be inappropriate. She already had some research from her conversations with customers. She wondered if she could do more to reduce the risk using the same approach. She decided to try.

Over the next three weeks, she mentioned her plan to some of the guests that routinely referred guests. The responses were divided. Several told her that they would not participate because taking some remuneration in exchange for a recommendation seemed dishonest. Recommendations needed to come from personal conviction, not payment. Others told her they thought the idea was a good one. Of course, they were already making recommendations and had not needed the extra incentive to do so.

She also talked to guests who, to her knowledge, had not made a recommendation and who were regular diners at her restaurant. Their feedback was also divided. Some liked the programme and assured her they would increase behaviour if they were there, whereas others said they didn’t believe it would affect their behaviour either way. A few shared her existing recommender’s perspective that payment in exchange for recommendations seemed dishonest somehow.

In response to the feedback, the owner decided to make a few changes to her plans. She decided not to launch the recommendation programme on a formal basis. Instead, she would create an informal reward programme. She would continue to track guests who made recommendations, and slip a note on their table to thank them for the recommendation. She would also give them preferred seating, the occasional bottle of wine or free dessert, in recognition of their assistance.

The programme would not be published, so patrons would not feel they were being bribed to make recommendations. However, based on the feedback, she felt that the gifts would help her cultivate loyalty among her most valuable customers.

The informal nature had an additional benefit. If the owner starts the programme with free items, and none were required, patrons might discontinue their behaviour if the programme was subsequently discontinued. On the other hand, if no incentives were offered or the programme was informal in nature, the financial commitment and associated risk would be lower.

As she walked through the risk assessment decision tree a second time, she decided that because of her ‘research,’ the assumptions about behaviours were no longer substantial risks to the programme. She was also confident that the results she anticipated, related both to revenues and expenses, were accurate. She was ready to move forward.

THE ANTICIPATED RETURNS TEST

When a company invests in a new manufacturing plant or expands production capabilities, its executive team usually constructs a model to evaluate the potential impact on revenue against the investment required. Of course, they make a number of assumptions in the process. Perhaps most importantly, they assume they can sell more products. Because building a facility does not guarantee that the product will sell, this is a substantial assumption.

Yet, the return on marketing investments, whose components are so directly tied to revenues, are less consistently evaluated on an ROI basis. Of course, there are exceptions. New facilities and products often are exceptions, but without channels through which they reach the market, and promotions so that the market is aware they exist, they are unlikely to sell. Many companies also do financial analyses on pricing strategies or channel decisions. However, promotions are frequently left out of the evaluation process.

When other aspects of marketing are assessed for expected returns before investments, and promotions are not, it exacerbates the nagging doubt executives have about the efficacy of their investments in that aspect of marketing. Worse yet, because there were only vague expectations relative to financial performance at the outset, marketers have little to defend—and executives have few tools to hold marketers accountable.

The fourth test non-marketing executives should run prior to approving funding for a marketing plan is designed to address these issues, and it is called the Anticipated Returns Test. This test evaluates the expected returns relative to the anticipated financial investments and provides a simple means of evaluating anticipated ROI. It is introduced in chapter 11, ‘Evaluating Returns on Marketing Investments.’

By running the Anticipated Returns Test and discussing the expected returns prior to approving funding, the executive team will be more committed to the investment and less likely to discontinue funding before the returns are received. The exercise can also improve accountability, minimise poor investment decisions, improve the accuracy of intermediate and retrospective measurements and reduce waste.

Before I describe the test in more detail, it should be noted that executives are not the only ones who have neglected measurements of financial returns on marketing investments in the past. Marketers themselves are often reluctant to commit to such a measurement process for many reasons. Some marketers are simply not comfortable with financial analysis, just as some non-marketing managers are confused by terms routinely used by marketers. To facilitate the measurement process, both sides must exercise patience and understand their colleagues’ strengths and challenges in the process.

Other marketers are reluctant to commit to measurement because they are concerned that they will be held accountable for outcomes that may not be within their control. For example, in the case study used in the Assignment Test section, the marketing department of the law firm, which frequently manages only the promotional aspects of the marketing mix, might be very reluctant to commit to outcomes given the partners’ reluctance to act as an effective sales channel. Without sales, appropriate pricing and quality legal services, the promotional efforts are unlikely to produce at their full potential. As such, these contingencies must be identified.

In other cases, the marketing team hasn’t attempted to measure returns because it has simply never been expected. By routinely running the Anticipated Returns Test prior to funding, the marketing team will become more adept at, and more comfortable with, the measurement of returns, and the company’s performance will benefit as a result.

How the Test Works

Whether conducted by the executive team or delegated to the marketing team for completion, the nonmarketing executive should request that the expected return and any assumptions associated with that return be outlined in conjunction with marketing plan development. To do so, use the following steps:

Step 1. In most cases, companies will need to begin with an estimate of revenue streams that assumes no incremental investment. In other words, the company should estimate what the revenues would be over the same period in which the marketing plan is expected to generate results, if it continued on its existing course, spending the same amount of money on the same marketing initiatives. Similarly, it should understand what the related expenses would be. This provides a baseline against which incremental revenues and expenses can be calculated.

Step 2. Next, the company should calculate a preliminary ROI ratio by dividing the expected returns under the status quo model by the expected expenses under the same model. This provides a good starting point for a comparative ROI.

Step 3. The company should begin its assessment of the proposed marketing plan with the last step of the Alignment Test, noting the projected revenue and related expenses. As discussed in chapter 11, these numbers should be adjusted to account for the perceived performance risk. For example, if the budget includes a line item for overruns, the company should include the budget overrun estimate in the total budget amount. Similarly, if the management team assesses the likelihood that the company will achieve the targeted revenue goals at 80%, the revenues should be reduced by 20% to reflect that risk. By calculating the ROI based on these new figures, the company can more easily compare the new plan to its predecessor.

Step 4. In many cases, it may be helpful to assess the incremental impact the plan will make. In this case, netting out the status quo revenues and expenses from the ROI equation may help the executive team evaluate the effectiveness of the plan.

Step 5. Once the ROI has been calculated, the executive team can evaluate the investment in incremental marketing initiatives against expected return rates on capital and other investments to determine whether the plan meets company expectations.

Step 6. Finally, the executive team should confirm that the marketing team has outlined appropriate completion, intermediate marketing and financial metrics to track progress and measure results.

In the same way that a company can estimate the potential returns on a single piece of equipment, this process can be used to evaluate the investment in an incremental marketing activity. However, the evaluator should be careful to consider whether the returns are tied to other activities or whether the incremental marketing activity will have a positive (or negative) impact on other aspects of company performance and account for these impacts accordingly.

Case Study: The Anticipated Returns Test in Action

The executive team at a mid-sized aerospace component manufacturing company sat around their board room table. The company’s new chief marketing officer (CMO) had just finished a presentation of its newly developed marketing promotions plan, which required a sizeable increase in budget over previous years. It was clear from the conversation following the presentation that the CFO was sceptical that the investment was worthwhile, whereas the CMO was equally passionate about the company’s need for change. After listening to the conversation for some time, the CEO stepped in and suggested they calculate the anticipated financial returns on the plan.

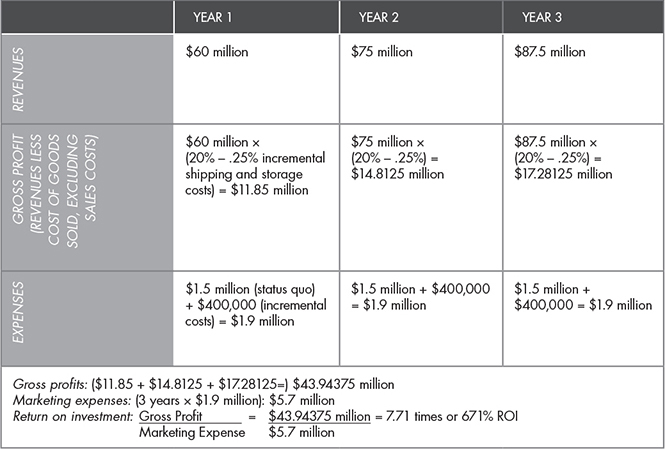

The CFO began by reviewing historical performance. The company had a small but stable share of its market. The market was mature, but the component was critical, and revenues, when adjusted for the impact of inflation and economic trends, had reached a plateau several years before. Revenues were estimated at about $50 million annually. The gross profits, after costs associated with production were deducted, was $10 million in revenues.

The company’s own customers were very loyal but so were their competitors’ customers. Because sales had not changed, and the situation seemed unchangeable, the company’s previous CMO had focused on efficiency, and marketing expenditure focused primarily on customer retention. The company’s marketing budget included some promotional expenditures, three marketing team members and four sales people. With compensation, benefit, payroll taxes and materials costs, the marketing budget had been reduced to $1.5 million annually.

Using these figures, the team calculated the ROI of existing marketing to be about 6.67, or 567% ROI. This level of investment, they agreed, provided a return that was higher than they could get investing the money in other activities or financial markets. Box 16-5 shows the status quo calculations.

Box 16-5: Status Quo Calculations for a 3-Year Period

When the new CMO joined the company, he spent the first several weeks visiting existing and prospective customers. These conversations led him to believe there were opportunities to increase the company’s market share. In particular, a number of the customers he had visited expressed frustration over the delivery processes. Just-in-time fulfilment practices had not yet been established in this particular industry, due largely to the size and shipping cost associated with the particular components they manufactured. However, the COO and CMO had developed a model that would allow the company to offer just-in-time fulfilment services, with modest additional expense. Unfortunately, the competitive nature of the industry would not allow the marginal costs to be passed along to the customers.

The CMO believed that if the company invested heavily in promotions associated with this innovation, it could snag market share before competitors had an opportunity to imitate the improvement. Because customers tended to be loyal once they had established a vendor relationship, the CMO believed an operational change and a short-term marketing push could deliver long-term financial benefits for the company.

The marketing plan proposed an incremental expense (associated with the revised shipping approach) of .25% of revenues in each year due to storage and higher per-unit shipping costs. In addition, the plan added two new sales professionals, at a cost of $240,000 per year, and $160,000 in incremental promotions.

Based on his conversations with customers, he believed that the new shipping approach would be extremely attractive to their customers and that they could easily increase revenues by 75% by the end of the third year. Specifically, he estimated that revenues would grow from $50 million in the previous year to $60 million in year one, $75 million in year two and $87.5 million in year three. The COO added that the company had the production capacity, so the gross margin percentage was not expected to be affected.

Using these figures, the team calculated the return on the marketing investment to be 6.5 times the investment, or 550% ROI, as shown in box 16-6.

Box 16-6: Anticipated Revenue Under New Plan for a 3-Year Period

The results of this test also looked impressive. At over 1000% return on investment, investing in this plan seemed a far better venture than could be obtained elsewhere.

Box 16-7: Incremental Return on Investment Under New Plan for a 3-Year Period

The results of this test also looked impressive. At over 1000% return on investment, investing in this plan seemed a far better venture than could be obtained elsewhere.

However, the team had not yet addressed risk. After a lengthy discussion, the team reduced projections to 45% growth, a level that even the sceptical CFO felt was likely, given the change. With this level of sales, the CMO said that the marketing budget should also change. The addition of a single sales person would be sufficient to handle both prospective lead generation and order-taking needs in year one. A second sales professional could be added in year two.

The risk-adjusted budget figures provided a return rate of 6.71 times the investment, or 471% ROI, very similar to the original plan. Not surprisingly, the incremental rate was in the same range, producing a 6.16 times the incremental investment, or a 516% ROI. Box 16-8 shows the calculations using the risk-adjusted budget figures.

Box 16-8: Risk-Adjusted Anticipated Revenues Under New Plan for a 3-Year Period

At the end of the conversation, the executive team, with the CFO’s agreement, decided that the plan sounded solid. Before the team was asked to indicate their approval, the CEO asked the CMO to review the metrics the team would use to track progress and indicate what corrective measures would be taken to correct deficiencies if they arose. Satisfied with the responses, the team approved the plan.

CHAPTER 16 SUMMARY

Many non-marketing managers, particularly CFOs, see a marketing plan for the first time when they are asked to approve the budget request. Whether the CFO has a very active role in evaluating marketing investments, or a less integrated one as a part of the executive team, there are four tests the CFO should use to evaluate whether a plan is complete, what kinds of financial returns are expected and whether it is ready to be approved and funded.

The Alignment Test provides a means of evaluating how well the plan is aligned with business and financial objectives. My research indicates that this is a key indicator of whether the plan will help a company achieve its objectives and whether the required executive support exists to execute a plan through to completion.

The Assignment Test ensures all the activities within a plan are effectively staffed. Even a well-constructed, wellaligned plan can fail if it does not account for staffing needs or secure buy-in from key team members. This test helps avert that issue by ensuring that every activity has been allocated to a specific resource who has, in turn, accepted that responsibility.

The Risk Assessment Test reviews the plan for critical assumptions. Although assumptions are normal in any planning process, assumptions constitute risk. This test is designed to ensure that the critical assumptions have been identified and mitigated if possible.

The Anticipated Returns Test evaluates the expected returns relative to the anticipated financial investments and provides a simple means of evaluating anticipated ROI. Calculating returns on marketing investments provides two substantial benefits: It makes it easier to compare marketing investments to alternative uses of cash, and it improves accountability and focus in the process of execution.