CHAPTER 2

Literature Review

This chapter reviews the literature on program and portfolio management, as well as project type and environmental complexity. A review, however, can only cover a subset of the literature written on a subject (Hart, 1998). The intent with this chapter, therefore, is to identify the major theories, tools, and techniques developed in program and portfolio management. To that end, the review focuses on four sets of literature: program management, portfolio management, project types, and organizational complexity. Within each of these categories, the literature is grouped by dominant subject areas. The review ends with an identification of a gap in the existing literature when it comes to answering the research questions, and identifies a set of hypotheses that guide the remainder of the research study. Parts of this review have been published before in Blomquist & Müller (2004b).

Project Portfolios and Their Management

Project portfolios provide frameworks for management to compare a variety of different projects in order to decide in which one to invest. Portfolio techniques were originally developed by General Electric/McKinsey and Boston Consulting Group (BCG), and showed a business’s competitive position and market prospects in a matrix or grid. Different positions on the grid suggested different marketing strategies, as in Figure 2 (Goold & Luchs, 1996). From such a corporate perspective, the optimum portfolio was often defined as one in which the products in the Cash Cows quadrant generate adequate cash flows to produce sufficient returns for shareholders, as well as cash to further develop the products in the Question Marks and Stars quadrants to replace the Cash Cows in the future. For such portfolios to be manageable, it is necessary that products be linked in a way that allows benefiting from the organization’s competencies (Scott, 1997).

Over time, the technique became a standard method for selecting projects for organizations. Research & Development (R&D) organizations especially used the technique to guide the decisions for project selection and resource assignments. To that end, portfolio management helped to do the right projects, whereas the complementary project management methods were used to do projects right (Cooper, Edgett, & Kleinschmidt., 2000).

With the increasing use of projects as a means to deliver products and services, the use of portfolio management techniques for governance of resource-interrelated projects steadily increased. Here, portfolio management techniques are used to guide organizations’ management decisions on prioritization of resource assignments across projects (for example, maximization of economic value, “fire fighting” troubled projects, minimizing risks, and maximizing a project’s long-term ROI).

Literature on portfolio management was found to address three major perspectives:

- Portfolio definitions and associated project selection techniques

- Planning and management of project portfolios

- Competencies for portfolio management.

Each of these three categories of literature is discussed in the following section.

Portfolio Definitions and Selection Techniques

With the increased use of projects as a development and delivery process for products and services, the management methods of doing a project right have turned into an organizational issue of doing the right projects. Project portfolios, as methods for decision-making across projects (e.g., through selection of projects and resource allocation between projects), becomes increasingly important for organizations in achieving their strategic objectives. This discussion emerged first in the R&D literature (Baker & Freeland, 1975; Schmidt & Freeland, 1992; Chien 2002).

The most popular model for portfolio definition was empirically developed by Cooper et al. (1997, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004a, 2004b, 2004c) for new product development portfolios. They showed that companies pursue at least one of the three goals of:

- Maximizing the value of the portfolio. This aims to maximize the desired objectives of the portfolio and uses various techniques, mainly financial models or scoring models, to identify the parameters for value maximization. The objective is to maximize commercial value of the portfolio at the given resource constraints by, for example, using net present value (NPV) or other measures for Return-on-Investment (ROI). The approach allows for automation of the decision-making processes by, for example, the use of decision support systems that collect required data from the respective organizations, process the data, and prioritize projects, as well as automate the resource allocation process (Iyigün, 1993). Contrary to their popularity, the ROI methods are often criticized for being too number-focused and not taking into account strategic or other non-financial aspects of the business. Some organizations use pre-developed criteria to score and finally rank their projects to identify those of highest priority. These methods lack acceptance, partly due to poorly crafted or outdated criteria, leading to disuse of the models. Cooper et al. (2004b), as well as many other authors, showed that these project selection techniques are associated with low performing portfolios.

- Achieving the right balance and mix of projects. Analogous to an investment fund, these portfolios balance risk (or other key parameters) to arrive at the perceived optimum balance of a portfolio. To visualize the result, individual projects are plotted in various grids that show the portfolio’s balance in dimensions, such as strategic fit, risk/return, long-term durability, reward, time-to-completion, and competitive impact, among other factors. Similar to the maximization techniques described above, the balance models are criticized for an exaggerated reliance on financial data and a lack of guidance towards achieving the right balance. In their recent research, Cooper et al. (2004b) showed that these project selection techniques correlate with higher performing portfolios and, thus, are better than those aiming solely for maximization of the portfolio’s value.

- Portfolios for linking strategy with projects. This approach is concerned with the fit of projects with the organization’s strategy. The strategic fit is enforced by either incorporating strategic criteria in the “go/no-go” decisions for projects or allowing funds only for projects aligned with the strategy. It is also known as the strategic bucket approach. This method ensures that spending is aligned with the organization’s strategy. The technique is criticized for being too time-consuming and somewhat hypothetical, as this process requires splitting resources in the absence of real projects. However, Cooper et al. (2004b) showed that this technique is correlated with highest levels of portfolio performance.

A popular method used to identify projects that do not (or no longer) fit into a portfolio is the one that uses stage gates for project exclusion. This is accomplished by providing an organization’s management team with certain sets of information at predetermined stages in projects, so that they can decide on the continuation or cancellation of individual projects. Companies using this method showed higher success rates on launch, sales, and profit of their new products (Cooper et al., 2000).

By comparing high and low performing portfolios, Cooper et al. found that higher performing portfolios include more innovative, riskier, and bolder projects, which are often larger, new-to-the-business, or new-to-the-world projects with high values. High performing portfolios also show a better balance in number of projects and resources available. Companies with high performing portfolios were also found to dedicate more resources to sales and marketing, and to allocate resources based on project merit (Cooper et al., 2004b).

The importance of the right set of projects in a project portfolio for a company’s future or market growth over time was identified by Wheelwright and Clark (1992). By looking at a case from the manufacturing sector, they recommend classifying projects by the degree of change in the product and the degree of change in the manufacturing process, which allows classifying portfolios by:

- Derivative projects, which are those involving only minor product and process changes

- Platform projects, with medium levels of change, and involving the development of the next generation products and processes

- Breakthrough projects, with the highest levels of change through new core processes and products

- R&D projects, which are outside the commercial project groupings listed above, but develop the know-how and know-why of new materials and technologies that eventually translate into commercial development.

Wheelwright and Clark (1992) recommend plotting the projects of an organization in a graphical representation of this classification, and then estimating the desired mix of projects by assessing the resource needs and resource capacity; they recommend then deciding on the specific projects to pursue with the existing resources. This helps to determine the type of projects to accept, decline, or eliminate in order to balance the strategic mix and ensure a steady stream of projects in the organization. Furthermore, their approach helps identify the need for future capabilities and development, as it also provides appropriate training and career programs.

By looking at all projects in an organization (not only R&D), Kendall and Rollins (2003) recommend developing portfolios through a three-stage process, which starts by ranking the projects and displaying these by their NPV, risk, internal/external orientation, and originator. The second step involves a ranking by each project’s contribution to the sum of benefits from all projects. The third step involves identification of the “strategic resource,” which is the primary resource for determining how many projects a company can complete. Finally, they suggest using NPV to identify those projects with the highest return for every workweek of the strategic resource.

In a related approach, Kerzner (2001) recommends graphically displaying the project portfolio in a grid that outlines the project phases and the quality of resources required. A project is displayed as a circle where phase and resource quality needs interconnect. The size of the circle shows the estimated benefits from the project, and a pie chart within the circle shows the percentage of the project that’s been completed to date. These techniques identify the projects eligible for the portfolio.

Over the years, a variety of decision-making techniques emerged for project selection. Often developed from operations research, a variety of qualitative or quantitative techniques were developed. Shortcomings with quantitative models include their inadequate handling of multiple evaluation criteria, interrelationships between projects, diversity among projects, as well as insufficient integration of R&D managers’ knowledge and experience. Therefore, R&D managers perceive models as difficult to understand and apply (Chien, 2002).

Recent approaches to project selections include that of “real options.” Here the (in)-stability of the project’s context in the future, and the differences in associated management approaches of the project, influence the application of traditional or more option like approaches to project selection. Often, organizations evaluate the choices between options or, in this case, real options, in a kind of decision tree (Loch & Bode-Greuel, 2001).

A wide variety of selection techniques, tools, methods, and applications is described in detail by Dye and Pennypacker (1999). The book’s common theme among 25 papers from different authors is the need to balance quantitative and qualitative information for portfolio decisions, and the need to select portfolio decision criteria depending on the organization’s type of portfolio and its strategy. Since an in-depth review of individual techniques lies beyond the scope of this study, interested readers are referred to the book by Dye and Pennypacker (1999) for more information.

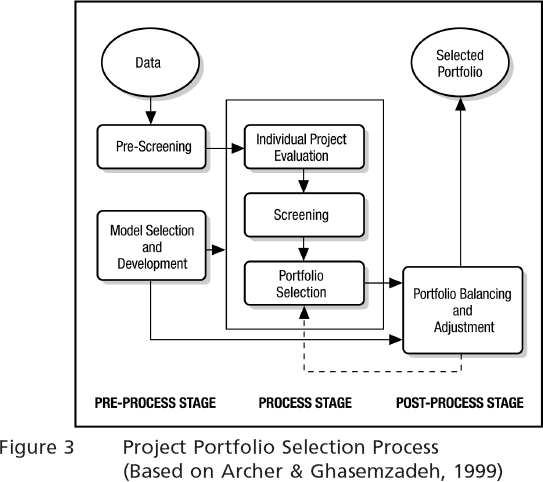

An integrated approach to project portfolio selection was developed by Archer and Ghasemzadeh (1999). Based on their review of existing selection techniques, they developed a three-stage process of pre-processing, processing, and post-processing of selection related data; see Figure 3.

Here, the pre-processing stage supports the elimination of infeasible projects, which reduces the workload during the subsequent selection process. During the processing stage, data of the individual projects are analyzed and processed into a common form as well as common qualitative and quantitative measures. During screening, economic calculations from the previous stage are used to eliminate non-mandatory or other projects that do not meet preset economic criteria. At the portfolio selection stage, outputs from the previous stage are combined to select a portfolio based on the objectives of the organization. This often results in a preliminary ranking of the projects based on the objectives specified for the portfolio, and an initial allocation of resources. Sensitivity analysis and other techniques are used to make final adjustments, as well as for balancing of the portfolio. During portfolio balancing and adjustment, the decision makers apply judgment to make final adjustments to the portfolio, for example, through use of matrices that graphically display the critical variables of individual projects. Model selection and development refers to the initial decision by the organization regarding which techniques to use at each stage of the process. Here, special consideration must be given to the need for a common format for all data, so that appropriate comparisons are possible. The process integrates the most widely used techniques for project selection and should be applicable for a wide range of possible project portfolios.

Planning and Managing Project Portfolios

Managing portfolios through a joint team of project managers and line managers (as resource owners) is recommended by Platje, Seidel, and Wadman (1994). This portfolio management team uses the individual project plans as input to develop a feasible (re)allocation plan for resources across all projects in the portfolio. Checks and updates of these plans are done regularly. That establishes stability in both the contents and process of the portfolio.

Using examples from several industries, Turner and Speiser (1992) identified the information requirements for portfolio-level planning by showing four different information systems that are needed for synchronized planning at the portfolio, program, and project levels. These four systems are the resource plans, work-package plans, resource schedulers, and team schedulers. Here, work-package plans are passed from the project managers to their portfolio managers for overarching resource planning. Work is then assigned to single disciplines using a resource scheduler, or to multidisciplinary teams using a team scheduler.

A two-level model for portfolio management was developed by Gokhale and Bhatia (1997). Here, the project goals and methodology are fixed for periods of approximately three months, then both are reviewed and, if necessary, revised. This approach allows for the reallocation of resources in the portfolio at the end of each three-month period. Through this approach, the system primarily supports projects with clearly defined objectives and less well-defined methods to achieve these objectives (Turner & Cochrane, 1993).

A scheduling process for projects in a portfolio is shown by Turner (2004). He suggests a six-step process, where:

1. Individual projects are proposed to the portfolio directors.

2. Individual projects are planned by the project managers, and resource requirements are determined.

3. Instead of adding a complete project plan into a giant “plan of plans,” each project is added to the portfolio resource plan as a single activity, with idealized resource requirements. This results in a master project schedule.

4. Total resource requirements are compared with resource availability and projects are eliminated until a balance between resource requirements and availability is roughly reached. Then, resource leveling takes place, which might impact the schedule and durations of individual projects.

5. A start date, finish date, and resource profile are determined for all the projects in the portfolio. The projects are then handed over to the project managers for execution within the set window.

6. Project managers then manage the projects and the associated tasks. For this, resources are requested from resource managers, or sometimes work-packages are handed over to resource managers, so that they take on responsibility for the work-package and assign resources to it.

This approach avoids the cumbersome development of a complex “plan of plans” of all projects, which is difficult to develop and maintain.

The managerial problems in business development portfolios were identified by Elonen and Artto (2003). They assessed two portfolios and related their findings to the literature. Through this, they identified six major problem areas:

- Inadequate project-level activities (e.g., through improper implementation of pre-project stages and infrequent progress monitoring)

- Lack of resources, competencies, and methods (e.g., through inadequate methods for portfolio evaluation, lack of resources, or extensive composition of steering groups and teams)

- Lack of commitment, and unclear roles and responsibilities (e.g., at the project level, but also between portfolio managers and other organizations, as well as a lack of management support)

- Inadequate portfolio-level activities (e.g., through overlapping tasks within and among portfolios, weak decision-making, and reluctance to kill projects)

- Inadequate information management regarding information about projects and its flow across the organization

- Inadequate management of project-oriented business (e.g., through low prioritization of projects, lack of project-business strategies, frequently changing roles, responsibilities, and organizational structures).

The study showed the need for more clarity of managers’ roles and responsibilities, and the practices for implementation of portfolio management in organizations. It also showed that many of the problems encountered in real-life portfolio work were not addressed in the current literature. Similar to Elonen and Artto (2003), Engwall and Jerbrant (2003) identified problems with project interdependencies, resource allocation, competition of resources, and short-time problem solving. Thus, it shows that a need exists for empirical research into the realities of portfolio management practices.

The last group of portfolio management literature addresses the competencies of project-oriented companies.

Competencies for Portfolio Management

Competences for the optimization of portfolios were assessed by Gareis (2000), using a multi-method approach. Portfolio coordination and distribution of information material, as well as participation in steering group and project meetings, were found to be important. He also identified program and portfolio management as distinct activities that emerge in organic organizations operated by empowered and process-oriented employees, where portfolio management serves as an integrative function to manage the dynamics of project-oriented companies.

The three aforementioned categories of portfolio management literature show three distinct perspectives, which address different timely stages in portfolio management. The first group addresses the ex ante stage, when portfolio definitions are made and projects are selected or rejected for entry in the portfolio. The second group of literature mainly addresses the management techniques needed for planning and managing the portfolio once projects have been assigned—thus, the ex post stage of a project’s execution in the portfolio. The third category addresses the competency requirements for the two previous groups, and is thereby timely independent.

Even though these differences prevail in the portfolio management literature, the practices described in these groups of literature are not independent of each other. Portfolios do not exist in a vacuum. They are often changed, adapted and refined, to better reflect an organization’s strategy or changing market conditions. To that end, the three perspectives are interlinked, as shown in Figure 3. Changes in, for example, the ex ante stage impact the practices at the ex post stage and possibly influence the competency requirements of the management resources. Portfolios are in a constant flux for the achievement of an organization’s objectives.

The next section reviews program management literature.

Programs and the Management of Programs

Up until the 1990s, considerable confusion about the application of the terms “multi-project management,” “program management,” and “portfolio management” existed. These terms were often used interchangeably, and program management and portfolio management were often referred to as groups of projects that share some sort of commonality (Pellegrinelli, 1997). In recent years, the literature became more concise and applied terms like “multi-project management” to the management of several smaller and often unrelated projects (Archibald, 2003). Program management is often described as connected with, albeit different from, portfolio management. Projects within programs share a common, overarching objective, and projects in portfolios share the same set of resources (e.g., Lycett, Rassau, & Danson, 2004; Turner & Müller, 2003). The most recent definitions for both management approaches are listed in the introductory chapter of this book.

Program management is often perceived as the top layer of a hierarchy consisting of individual projects (Kerzner, 2001). Program management goals focus on improving efficiency and effectiveness through better prioritization, planning, and coordination in managing projects (Pellegrinelli, 1997), as well as in developing a business focus by defining the goals of individual projects and the entire program regarding requirements, goals, drivers, and culture of the wider organization (Lycett et al., 2004). The literature on program management can be classified into three categories:

- Program management as an entity for organizational structure

- Program management processes and life cycles

- Competencies for program management.

These three categories are described in the following:

Program Management as an Entity for Organizational Structure

Program management is often described as the next higher organizational hierarchy level above project management. Managers in this function are the intermediaries between higher management and operations personnel, implementing an organization’s strategy. Program managers, therefore, link an organization’s strategy with the economic implementation through operations. They do this by setting the context for projects and project managers to operate (Pellegrinelli, 2002).

Most of the literature suggests program management to solve problems of linking projects towards a common objective. The approach is, however, also used to address problems of linking projects with their organizational environment. Levene and Braganza (1996), for example, suggest splitting larger business-process re-engineering projects into programs of projects, to overcome the lack of management support and isolation of one-off projects. By implementing planning steps on a rolling-wave basis, the outcomes of projects in a program can be interlinked. With this, a more realistic and feasible plan can be developed.

A continuum of hierarchical management structures for programs is described by Gray (1997). These structures span from loose programs or multi-project groups managed under a single project management umbrella with little control and empowered project managers, up to highly controlled projects that are a function of the project management planning activity and controlled by the program manager and the program stakeholders. Gray suggests choosing a management structure based on the desirability and feasibility of the approach. He suggests that such decisions should be taken on the basis that a management structure is chosen that yields the most beneficial outcome for the program and is, in fact, doable for the organization.

Program Management Processes and Life Cycles

The processes for project and program management are often described as being similar in nature, albeit different at the detailed level. Both comprise a sequence of steps (e.g., Lycett et al., 2004; PMI, 2003; Thiry, 2004) for initiation or identification, planning or definition, executing, controlling, and closing.

PMI (2003, p. 127) states that these steps are most likely helpful, but not complete explanations of the program management processes. Thiry (2004, p. 252) identifies a program life cycle along a hierarchy of projects, programs, and strategy that is based on:

1. Formulation (sense-making, seeking of alternatives, evaluation of options, and choice)

2. Organization (strategy-planning and selection of actions)

3. Deployment (execution of actions—projects and support, operational activities, and control)

4. Appraisal (assessment of benefits, review of purpose and capability, and re-pacing, if required)

5. Dissolution (reallocation of people and funds, knowledge management, and feedback).

Thiry (2004) describes activities related to the execution stage of a program as assessment and management of the environment and communication, as well as the identification of emerging challenges. This includes a focus on the interdependencies of projects, the program manager’s level of intervention in assessing major deliverables, and the output-input relationship of projects in the program, as well as audit and gateway control.

Thiry (2004) defines the activities that occur during the control phase of a program as assessing the need for plan reviews and changes, considering key performance indicators against deliverables, and making decisions to continue, realign, or stop projects.

Competencies for Program Management

An empirical framework for program management competencies was developed by Pellegrinelli, Partington, and Young (2003) and by Partington, Pellegrinelli, & Young (2005). Their framework consists of four levels of competencies with 17 attributes arranged into three groups of relationships that are then managed. These relationships include self and the work, self and others, and self and program environment. The four levels represent an increasingly widening view from focus on details only to appreciation of contextual and future consequences. Lower levels require the understanding of the details and the relationships between activities. The next level works at a summary level, without getting overwhelmed by the details. The third level involves the understanding of the entire program, plus activities that include gaining an understanding of the issues and outcomes for key stakeholders. The highest level holds an overall view of the program and selected details; it appreciates the impact of program decisions and actions outside the program, as well as potential future consequences.

In agreement with other authors, Pellegrinelli et al. (2003) also identified a major difference in the requirements for project managers and program managers. They found that the former should be more focused on strict planning, management, and solving of technical issues, whereas the latter should be increasingly tolerant of uncertainty, more embracing of change, and more aware of the wider business influences. Therefore, program managers need to be better improvisers than implementers of structural approaches (Pellegrinelli, 2002).

This review of program management literature showed three distinct perspectives towards the subject. The first one took an organizational view and looked at the program manager’s role in implementing an organization’s strategy through programs of projects. The second category looked at the processes needed to manage programs, while the third group identified the underlying competencies required for program management. As in the case of portfolio management, these three categories are not independent, and are linked with each other. Programs and their management are continuously aligned with an organization’s strategy and business conditions. Depending on the duration of these programs, these adaptations may vary in pace.

The preceding literature review provides insight into the differences between program and portfolio management concepts. However, it does not provide a clear understanding of the roles and responsibilities of managers working within those frameworks. This understanding will be addressed in the empirical investigation described further on in the report.

Project Types and Program/Portfolio Management

Differences in project types were investigated, among others, by Shenhar (2001). His popular model uses a two-dimensional matrix of project scope and technological uncertainty to identify different project types with different management requirements.

Turner and Cochrane (1993) identified differences in project type depending on the extent that goals in a project and the methods for achievement of these goals are understood in a project. In a 2 x 2 matrix (as shown in Figure 4), he identifies four different project types, depending on low or high clearness of objectives and methods. Each of these project types requires a different management approach to achieve the project’s objectives.

The four different project types are:

Type 1: Projects with well-defined goals and well-defined methods to achieve those goals. These projects are well understood. It is likely that similar projects were undertaken in the past. The participants will most likely be experts in the technology that is applied within the project. These projects are often engineering projects, such as maintenance projects whose project plans state sequences of well-defined activities.

Type 2: Projects with clearly defined goals, but poorly defined methods. Here, the functionality of the final product is well understood, but new, and it is not yet known how to best achieve this functionality. These projects are usually product development projects, which are planned in terms of the final deliverables.

Type 3: Projects with goals that are not clear, but well-defined methods or life-cycles to achieve them. These projects are often IT application development projects, which are planned in terms of life-cycle stages—where goals are defined in conceptual terms, but their specification is refined through the stages of the project.

Type 4: Projects where neither the objectives nor the methods are known. What is known is the business problem to be solved or an opportunity to be captured. So the emphasis is on identifying the objectives of a product or service that could solve/capture this problem and then treating it as a Type 2 project. These projects are often organizational change or research projects.

Crawford, Hobbs, and Turner (2004) showed that grouping of projects is an essential step in portfolio management. However, since the categorization purpose for portfolio management is different than it is in project management, the existing systems are rendered inappropriate for portfolio management. The model developed by Crawford et al. (2004) is based on 32 different purposes for classification and 37 attributes to classify projects. While it is more advanced in terms of applicability to program and portfolio management, the system does not outline the relationship between project groups/classifications and the associated portfolio management practices, roles, and responsibilities.

Environmental Complexity

The axiom that organizations adopt different management styles to meet the situational demands of their environment is one of the traditional themes in management literature. The concept is based on Contingency Theory, which claims that the characteristics of leadership and the situational requirements must match in order to produce the best possible results for an organization (Burns & Stalker, 1961). More recent developments in this field indicate that organizations often operate in several markets in parallel (such as national and international, or product development and organizational change projects) and, therefore, are required to match several environments simultaneously. Traditional bivariate contingency relationships, therefore, are seen as being too static to reflect organizations’ dynamics (Galunic & Eisenhardt, 1994). Research suggests that dynamic environments require experiential product development using frequent iterations, testing, and milestones (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1995). Environments, therefore, can be modeled on a simple-to-complex continuum, with simple being a well-understood environment for which reliable, effective ways of dealing exist. Complex environments are poorly understood, and reliable, effective ways of dealing with the environment are not known to the organization. The extent of change in the factors representing the environment is defined as its stability. This stability ranges from stable to turbulent (or dynamic) environments (Pethis & Saias, 1978).

A study by Bettis and Hall (1981) indicated that portfolio management is mainly used either by diversified firms that use portfolio planning techniques to aggregate business for strategic analysis and repositioning, or by dominant, vertical firms to guide diversity away from low-growth sectors. By assessing corporate results, the study indicates that companies using portfolio management better fit their environment. After implementing portfolio management, two out of the three firms assessed in the study substantially improved their market position relative to their competitors. The use of portfolio management was mostly triggered by poor financial performance and the perception that strategic issues were not surfacing.

In summary, the underlying organizational approaches and distinctions in roles between line and project management (such as line, project, program, and portfolio managers) are not yet understood and require further investigation (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1995).

The review of literature indicates a relationship between environmental complexity and the use of organizational approaches, such as program and portfolio management. This forms research hypothesis 1 (H1):

H1: An organization’s perceived environmental complexity is directly related to the use of program and portfolio management practices.

The review of project types shows a contingency between project type and project management approach. With programs and portfolios representing a higher-level dimension of project management, it can be hypothesized that these contingencies are also reflected at the program and portfolio level. Therefore, research hypothesis 2 reads:

H2: Different project types are correlated with different program and portfolio management roles and responsibilities.

Research hypotheses 3 and 4 are derived from the results of the aforementioned Bettis and Hall (1981) study, with H3 addressing the depth of program and portfolio management implementation in the organization, and H4 addressing the different roles and responsibilities associated with it:

H3: Governance practices in program and portfolio management differ significantly between high- and low-performing organizations.

H4: Middle managers’ roles and responsibilities in program and portfolio management differ significantly between high- and low-performing organizations.

Research assesses the practices, roles, and responsibilities of middle managers in program and portfolio management, as well as the impact of project type and an organization’s environmental complexity on these practices, roles and responsibilities. The variables for project type and organizational environment are classified as independent variables. Program and portfolio management practices, roles and responsibilities are classified as dependent variables. The high-level research model is shown in Figure 5.

The results will be structured by low- and high-performing organizations. This allows drawing theoretical conclusions, as well as identifying “best-practices.”

The study’s methodology is described in the next chapter.