CHAPTER 4

Managerial Implications: What Middle Managers in Successful Organizations Do

This chapter is a discussion and summary of the findings from the Methodology and Analysis chapter. It shows how high performing organizations structure themselves to handle the complexity stemming from their own organization, their types of projects, and their clients’ requirements. The chapter starts from a broad, organizational-wide perspective and shows the breadth and depth with which high performing organizations implement program and portfolio management practices. Then, the perspective changes towards the activities of middle managers in these organizations. Finally, the framework for roles and responsibilities, developed in the previous chapter, is discussed in detail and reconciled with existing practices described in the literature. Suggestions for further literature are provided for interested readers. The chapter ends with a set of practical recommendations for implementing program and portfolio management.

Organizing for Program and Portfolio Management

Organizations in the study adopted one of four possible governance structures:

- Neither program nor portfolio management

- Program management only

- Program and portfolio management (hybrid)

- Portfolio management only.

Assessment of organizational performance by governance structure showed that hybrid structures perform significantly better (p < .05) than all other governance structures.

Those organizations using neither program nor portfolio management perform lowest, while those using either program or portfolio management perform slightly (but not significantly) better. Figure 9 shows the relative performance of organizations in different governance structures. Statistical details, as well as details on average performance of projects, programs, and portfolios in different governance structures are provided in Table 16 and 17, as well as Figure 13 in Appendix C.

This is supported by the Canonical Correlation Models developed in the Methodology and Analysis chapter. These models showed that organizations’ differences in performance are related to their ability to adapt to changing situations. Higher performing organizations are able to balance the variety of requirements, both internal and external, through appropriate roles in the organization. Low performing organizations focus too much on their internal administration and are lacking roles to appropriately address, for example, the specific technology and time requirements stemming from their project types. Furthermore, they are lacking roles for dealing with the organization’s environmental complexity, which includes managing the internal stakeholders and decision-makers.

These issues are addressed through program and portfolio management roles. Program management roles executed by middle managers ensure a cohesive set of requirements stemming from a common (program) objective. It moves the program (with all its projects) in the center of the organization’s activities. That provides a vision for the organization and shifts priorities away from internal (administrative) tasks to external customer delivery tasks. It builds awareness for the organization’s primary reason for existence: to deliver value to its customers.

Portfolio management roles executed by middle managers balance the organization’s environmental complexity through clearly defined processes and criteria for project selection, as well as decision-making authorities. Such workflow:

- Simplifies decision-making processes

- Identifies and eliminates projects and tasks not related to the organization’s strategy

- Allows project and program managers to focus on their delivery tasks.

The combination of program and portfolio management roles, therefore, maximizes effectiveness and efficiency of the organization’s operation.

Managers’ Activities in Program and Portfolio Management

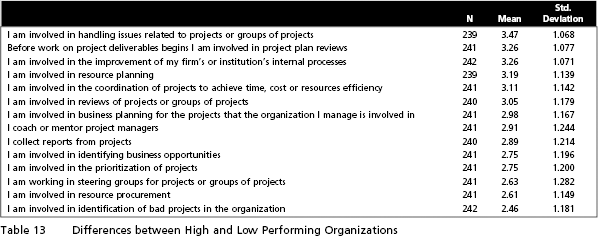

Based on the qualitative study, a number of roles were identified. As shown in Table 12, managers devote most of their time to the handling of project-related issues, followed by plan reviews and improvement of processes. The least time is spent on resource procurement and identifications of bad projects.

Differences in the amount of time managers spent in their different program and portfolio management roles were found between high and low performing organizations. Managers in high performing organizations devote more time than managers in low performing organizations to:

- Handling of project-related issues

- Review of projects

- Work in steering groups

- Procurement of resources

- Identification of bad projects.

Priorities seem to differ slightly between some activities. Managers in low performing organizations put nearly as much time into improving internal processes as do their counterparts in high performing organizations. However, they spent much less time on reviews of projects and groups of projects, as depicted in Table 13.

The reported “other activities” also differ between managers in high and low performing organizations. Managers in high performing organizations perform activities that are more:

- Strategic in nature

- Customer oriented, in order to develop value for clients

- Business related, as opposed to internal or administrative work.

Examples of reported “other activities” of managers in high performing organizations include:

I am involved in working with the clients in setting the expectations for their projects after we understand what they actually need the project to do. What a client wants a project to do and the reality of what we can deliver given the clients’ economic capability are many times two different things.

I am involved in qualifications based selection—preparing qualifications packages, orchestrating qualifications presentations, scope development, contract negotiations for most projects in my programs and portfolio.

Strategic Planning for IT is made yearly with Clients and my team of Coordinators.

Provide the organisation [sic] an overview of opportunities and project portfolio and utilization.

Taking programs through the stage gate process (manage core teams, prepare for stage gate reviews, etc.)

Managers in low performing organizations often report their “other activities” as being more administrative, such as documentation of standards and routines, or internal improvements.

Examples for managers’ roles in low performing organizations include:

Involved in defining and documenting standards, policies and guidelines for project and technology governance.

Co-ordination of international projects and routines to make it easier to work with cross-border projects. Also development and training of personnel in the projects takes a moderate extent of my time.

Similarities between these groups were found in their roles for project selection and project prioritization.

Middle Managers Roles in Program and Portfolio Management

The following describes the process underlying the roles listed in Table 3.

Prior to involvement in project-related activities, middle managers perform business planning and resource planning activities in relation to the organization’s annual plan. Upon identification of new projects, they engage in project selection activities—which differ according to the nature of the organization—and accept, change, or reject a project. Companies subsequently start coordinating their activities as well as tasks to improve portfolio efficiency. They perform resource procurement and continuous project plan reviews for changes in resource requirements, in order to match resource availability (e.g., contingent on other projects) with the resource needs of the new project. This process continues throughout project execution, as every change in the resource requirements affects any one of the projects in the portfolio. Once the new project is in the execution stage, managers use regular reporting to identify troubled projects and to trigger remedial action or cancellation of a project. Throughout the execution stage, portfolio managers participate in internal steering group meetings, during which they disseminate portfolio-related reports. These reports are aggregations of project reports; portfolio managers then determine project priorities in collaboration with other members of the steering group. For those projects that are identified as being inefficiently managed, portfolio managers initiate reviews, coach project managers, or handle issues as otherwise required. To improve efficiency, they also engage in the organization’s overall process improvement activities.

These activities are performed using a wide set of tools (e.g., aggregated red/yellow/green reports accumulated from individual project reports, organized into an overall list of risky projects and those with the most potential for impacting business results). Other tools used are time and cost information from enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems and profit and loss statements, as well as product roadmaps and strategic plans. The different roles are further described below.

Portfolio Management-Related Roles Prior to Project Execution

Business Planning

Middle managers within the companies interviewed engage in business planning as a result of previous strategic product or service decisions by upper management. Guided by their organization’s strategy, the managers develop short- or medium-term business plans, which either reflect a company’s existing strategy or serve as strategic responses to market pressures or competitor moves. These decisions lock out or lock in the organization in terms of future alternatives, for example, through development of a certain technology, entering of specific markets, or work with particular customers or systems (Ghemawat, 1991).

This is done at regular planning meetings, but also ad hoc in cases of larger marketing opportunities that require immediate response. For these business plans, managers develop the portfolio strategy, high-level product or service roadmaps, associated skills requirements, as well as implementation plans including schedules and budgets. This defines the operational activities needed to execute an organization’s strategy, as summarized by one of the managers interviewed:

A distinction which has just occurred to me is that (in my company) we use the term “portfolio” to define “the set of activities which are funded for the current year.” We talk about “this year’s portfolio,” or “next years’ portfolio”; whereas with projects and programmes [sic], we talk about them in life cycle terms—for example, as being in “definition,” or “delivery” and so on…

Cooper et al. (2004b) point out the importance of product roadmaps for New Product Development (NPD) portfolios. The roadmap outlines how management wants to achieve their desired objectives, both in terms of products as well as technology, and allows for identification of needed capabilities, which can then be planned for in terms of time and budgets. Clark and Fujimoto (1991), as well as Nobelius (2001), identify roadmap development as a critical balance of NPD project scope and its fit to the organization’s project portfolio.

Project Selection

Based on the business plans developed in the preceding step, managers select a portfolio strategy and associated project selection criteria. A typical selection technique described by one of the interviewees was:

We started with establishing the simple process to review new ideas and the flow of tasks that need to take place to validate them. We rapidly moved to the definition of the metrics by which projects could be fairly assessed against one another. We had five dimensions with level of investment required, attractiveness from an ROI/Payback standpoint, alignment of the project with the main company strategies, technical fit and chances of success. Each dimension had a series of criteria (1-7 max.) and all projects were then ranked in matrices to identify the most promising for next stages as well as the worse ones to stop rapidly.

Other interviewees emphasized the need for NPD products to complement existing projects in the portfolio, the fit of project objectives with organizational strategy, and the multi-dimensional aspects of economic decisions for project selection. Economic selection decisions were particularly impacted by the product’s capability for growth, its capability to be sold across several markets, and the combination of time-to-market and expected returns.

A wide variety of project selection techniques exists. They can be categorized in numerical and non-numerical selection methods. Critical questions for project selection were raised by Nobelius (2001, p. 267):

- How well is the project related to the overall strategy?

- Can the project increase the knowledge and capability of the firm?

- When could this project be implemented?

- How dependent is the project on other subsystems?

- Is there any fallback or backup solutions if the projects fail?

Cooper et al. (2004b) identified the strategic bucket approach (described in the Literature Review chapter) as being associated with high performing NPD portfolios. Other authors, such as Meredith and Mantel (1999) favor weighted scoring models for three reasons:

- The possibility to include multiple objectives of all organizations involved

- Easy adaptation to changes in the management philosophy

- No bias towards the short run, inherent in profitability models.

An in-depth assessment of project selection techniques is beyond the scope of this report on roles and responsibilities. Interested readers are referred to Englund and Graham (1999), Dye and Pennypacker (1999), Blau, Pekny, Varma, and Bunch (2004), or Cooper et al. (2004a, 2004b, 2004c).

Resource Planning

This role includes the development of a skills inventory needed to execute the project in the portfolio, as well as the processes for resource procurement decisions. It includes, among others, criteria for hiring new resources or using temporary external consultants, as well as internal or external training of existing human resources.

One of the managers who was interviewed described his resource planning activities related to portfolio management as follows:

I have to decide who is going to work with what, balancing resources and secure new resources.

Another manager describes the problem of resource planning and synergy identification:

On the inventory side, typically we find that there are too many projects going on and too few resources to focus on them, so most projects move at a snail’s pace. In large organizations, it is not uncommon to find duplicate projects underway in different parts of the company.

Some of the organizations interviewed keep the level of permanently hired resources at about 80% of the needed resources for their portfolio work, and engage external consultants on a temporary project basis as needed. This ensures continuous utilization of their employed workforce, even in times of slightly lower than normal levels of business, and allows filling peaks of workload with temporary resources.

Engwall and Jerbrant (2003) identify the resource allocation syndrome as the number one issue in multi-project organizations, because of frequent re-assignments of resources to different projects in a portfolio. This is also described by the interviewed managers:

Of course, you can move people between projects. However, if you do that too frequently, it becomes difficult to keep up with the schedules. It doesn’t work. It causes delays, which lead to even more resources sent to the project. These resources then need to first learn about the project, so the quality starts to suffer.

The limiting factor for the number of projects is the number of programmers I have for the moment.

Turner (2004) describes failure in planning of resource assignments as a problem caused by prioritization of projects and subsequent mechanistic allocation of resources to these projects. This leads to all-or-nothing effects, where high priority projects get all resources and lower priority projects none. He suggests a more balanced process to plan for resources in a portfolio context.

Resource Procurement

This role ensures that the procurement of resources for the projects in the portfolio is done in an economical manner or otherwise aligned with the organization’s strategy. As described in the paragraph above, some of the organizations interviewed have long-term relationships with specialists to engage them in projects on an as-needed basis. From a middle manager perspective, it lowers the risks for the portfolio because of well-known skill levels and economic conditions for procurement of individual resources. One of the managers in the interviews reported:

We group projects and my role becomes one of ensuring that all-important projects have the resources from within our own set of competence. If we lack competence I have to procure it.

Survey respondents reported their responsibility for keeping and developing skills, knowledge, and capabilities of resources working within the program or the portfolio. One of the managers stated:

I am responsible for setting annual business goals, target marketing, opening new program relationships, selecting alternative projects or clients, and keeping core expertise.

Little has been written in the portfolio management literature on this subject. Kendall and Rollins (2003) suggest identifying the strategic resource, which, more than other resources, contributes to the results of the projects in the portfolio and thereby causes a risk because of constraints in its availability. The value of resources with equivalent skills for the entire portfolio should be taken into consideration when making procurement decisions.

Project and Program Plan Review

The role of middle managers in plan review is that of a critical assessor of the plans made by managers of projects and programs. This is a quality assurance activity to ensure validity, reliability, and credibility of an organization’s plans. Organizations interviewed in this study use these reviews to assess the feasibility of the project or program in light of the organization’s objectives and constraints. A statement representing the scope of this role is:

I have to keep track of ongoing projects related to IT or projects that use resources within the IT department—to regularly follow up these projects regarding status, resource usage and delivery times

Questions asked during these reviews are, among others:

- Are the project and program objectives achievable with the current plan?

- Are the resources available, or can they be procured, for plan execution?

- Are resources used most economically?

In addition to reviews at the planning stage of projects, it is increasingly common to report project progress to management at project phase end. That is followed by stage gate (or toll gate) decisions by management on continuation or discontinuation of the project into the next phase. At these stage gate meetings, middle managers are involved for project and program plan reviews, as one of the interviewees reported:

As a principle, we negotiate the budget on an annual basis, even if our perspective is one of three years. New opportunities or problems arise frequently in our business and must be handled appropriately. That can be through prioritizing within the portfolio, or by asking for more money. We use the steering group meetings for that, where a business case for re-prioritizing projects or increasing the number of resources is presented. Through that we keep middle management involved.

Cooper et al. (2000) describe the stage gate process in portfolio management.

Program Management Related Roles Prior to Project Execution

Identification of Business Opportunities

Middle managers involved in marketing activities are often also involved in the identification of business opportunities. Here, they take on a program management perspective to identify clients’ business needs and develop solutions in the form of projects or programs of projects that fit both their organization’s strategy and their client’s needs. One of the interviewees reported on the changing role of managers in the identification of business opportunities:

The program managers become more of engagement partners and they are expected to farm more business.

The business opportunities identified by the program manager are then subject to approval by the portfolio manager, or the Steering group, sales manager or owner of the firm in his/their role as portfolio manager. One respondent said:

As the owner, I make the ultimate decision on which projects we will bid on and I review the planning and results of our associate project managers.

According to the organizations interviewed, this role often includes the breaking down of clients’ business requirements into smaller entities, which are then translated into more technical requirements for a possible solution. These requirements are then taken to the manager’s organization to assess their feasibility.

Frame (1994) describes the importance of understanding the customer’s needs and requirements at this stage of a program. Mistakes at this stage are likely to become very expensive to correct at later stages in the program. He suggests involving analysts, who are not only versed in their technical and business arena, but also possess personality traits that help build credibility with a customer.

Synergy Identification

Within this role, the manager identifies synergies across the program or portfolio, by identifying similar processes, tools or techniques, as well as existing solutions for some of the development tasks in the projects. Interviewees reported:

We have a requirement to standardize among our products to the extent that 80% of them are common.

In what is basically a knowledge management issue, the manager is faced with identification and usage of existing know-how or solutions. A study by McKinsey (Ealy & Soderberg, 1990) revealed that over 40% of product design issues at Honda were already resolved in prior programs, which caused 30% of design time to be wasted solving problems that were previously solved. The role of managers is, therefore, not only to have insight in past and neighboring programs, but also to encourage project team members to actively seek synergies and ways to implement them. Synergies become a way to transfer knowledge between projects (Nobeoka & Cusumano, 1995).

Resource Planning and Selection

This role includes planning for resources at the program level, which includes determining the resource assignment strategy across the projects in the program. It includes working with portfolio managers to determine the resource needs and capabilities, and supporting project managers in resource leveling, for them to develop reliable project plans.

A practical application was described by one of the interviewees:

The programmers have one or two areas that they know best. They could not work on every part of the system. They work fastest if they are in their main area, so we try to have a mix of competences. We have three matrices, a resource matrix linked to a skills matrix (a spreadsheet that shows what they cover and what they do not cover). The third matrix is on the different systems areas and what skills are needed for those areas. Making a list saying this person knows about this area and another list saying what skills we have available for work.

The overall efficiency of the program is dependent on the allocation of human resources between projects in the program (Hendriks, Voeten, & Kroep, 1999). Payne (1995) describes the need for a balance of resource requirements from projects and resource availability in organizations, together with a practice of commitment of allocated resources to projects. The ability to select resources has been described as especially difficult for program managers in multi-project organizations, because of the numerous dependencies that exist, for example, between departments, subcontractors, project teams, and projects in the program (Danilovic & Sandkull, 2005). Because of that, Eskerod (1996) showed that program managers should do their “head-hunting” for the right resources in the pre-sales phase of a project.

Very large programs may suffer from a lack of resources in particular geographic areas. One manager reported in the interviews about their large infrastructure projects, which are large enough that they can subcontract all suppliers (and their machines) in a region and still have to look abroad to satisfy the demand from the program. A large proportion of his work is to solicit tenders and evaluate ways to attract new subcontractors from abroad.

Program and Portfolio Management-Related Roles During Project Execution

Identification of Bad Projects

Within this role, managers use a variety of information sources to identify troubled projects. These include project reports or consolidated portfolio reports (often using red/yellow/green indication for project status), cost and time performance measures against plan, and earned value results. These are complemented by reports on organizational results, profit and loss statements, cost, revenue, and utilization reports.

One of the managers interviewed described it as:

The day goes by in monitoring projects, work with project teams, follow-up with the project managers on where we are in the project, especially the commercial aspects, such as money, final prices, etc.

A second manager described it like this:

I am the manager of what we call a Value Management Office. This Office is responsible for supporting senior management decisions on Information Technology initiatives through value and risk analysis of proposals. We also manage all project management processes as well as appropriate project delivery reviews. We provide reporting to Executives of all IT projects on progress, status and risks.

Managers’ ability to detect troubled projects is linked with the organization’s communication system. An open exchange of performance results of projects and the organization’s support of this process allows for corrective action in case of plan deviations. An open communications culture, together with contemporary portfolio management software that processes qualitative and quantitative information, allows the building of an early warning system to detect projects that deviate from plan at the earliest point in time. Müller and Turner (2001) showed the importance of communication for project success. They identified communication management as the Knowledge Area with the strongest impact on results in IT projects.

Participation in Steering Groups

In this role, managers accept the ultimate responsibility for project success by being a project sponsor or member of the project steering group. A steering group is made up of representatives of a project’s buyer, supplier, and sometimes also the subcontractor’s management. Through work in the steering group, managers review plans, accept deliverables, and ensure the linkage between the project and the organization’s strategy. In steering group meetings, managers are kept informed of project progress, decide on changes to the project, and are able to take corrective actions if projects deviate from plan.

One of the interviewees described these meetings as follows:

The steering group meets on a monthly basis. There we go through our projects and activities from a company-wide perspective. Participants are management, plus product management and project managers of the important projects—those that cost most money. We use a simple reporting—where are we in accordance with the schedule and where not, how do we do money-wise, and whether we have an issue with the marketing organization that should get the product.

Karimi, Bhattacherjee, Gupta, and Somers (2000) showed through empirical research in the IT industry that the use of steering groups is positively related to an organization’s success with its projects. Steering group meetings were also identified as arenas for political fights for resources (Guimaraes & McKeen, 1989; Eskerod 1996). Managers in these meetings work hard to get the best ranking and resources for their projects, as well as the most attention from top managers in order to succeed with their interests. The importance of these meetings is beyond the tactical level of the individual projects dealt with by the steering group. It is a meeting of strategic importance for middle managers.

This is supplemented by many other meetings that consume much of the middle manager’s day, such as meetings with staff, stakeholders, clients, etc. for solving issues, sharing information, or negotiating agreements. As one manager reflected on his work:

About 50% of each day is composed of meetings and developing relationships with senior executives of the customer organization. Some of that is normal communication, building of trust, and a way of setting customer expectations.

Prioritization of Projects

In this role, managers determine the relative priority of their projects. The difficulties in doing this are explained by one of the managers:

To sell a product earlier than our competitors, we need to have it in time. If the project gets delayed we may have to cancel it. We have to think twice before we prioritize. It has been shown again and again that projects that took too much time will never lead to something. Those that were successful were the quick and short projects. Because of that, we try to do things in small pieces and try to accomplish something quickly. Big projects, on the contrary, take such a long time that no one will have the product in the end. Competition is faster and faster.

Priority is assessed in regular intervals, so that projects can be stopped when other, higher priority projects should be pursued. Assessment of project priority is often done at stage gate meetings or regularly scheduled portfolio meetings, where decisions are made to continue with the current project or invest the resources in a higher priority project. One of the interviewees stated that:

The outcome of the weekly portfolio management meetings is a set of spreadsheets that show the projects listed in priority order under each portfolio. We are currently running three different portfolios. This ranking of projects is used in the allocation of resources and the arbitration of those projects as they compete for resources, such as developers, development environments, testers, testing environments, etc.

The meetings described above are important for getting agreement on the ranking of projects, as well as selection and allocation of resources.

Cooper et al. (2000) describe the mechanisms of stage gate processes. Various prioritization techniques are described by Dye and Pennypacker (1999).

Coordination of Projects

This involves the balance of time and resources to allow all projects in a program to be finished within the planned time frame. A change in the schedule of one project in a program has a knock-on (or domino) effect on neighboring projects, with impact on these projects’ deliverables or resources. One of the interviewees described this as follows:

If I say that a project starts in September and finishes in two years time, then this is dependent on another ten projects keeping up with their milestones and toll gates. If one project starts to slip, then this impacts all others. Therefore, it is important to keep the schedules. If a project starts getting delayed, then immediate action is required to recover the time lost, because this cannot be done at the end of the project.

In this role, managers coordinate the requests from project managers for changes in resource schedules or timings of tasks.

Engwall and Jerbrant (2003) showed that project schedules are often changed due to weaknesses in their planning. Within programs, a change in the schedule of one project has an additional effect on the neighboring projects, which either depend on the first project’s deliverables or resources. Fricke and Shenhar (2000) argue that a certain level of stability should be maintained, so that the organization’s projects could be completed.

Collection and Aggregation of Reports

Middle managers collect reports from project managers and aggregate them for higher management and other stakeholders. Managers interviewed were provided with detailed and summary information. However, they also often collected further information that was not readily available in existing summary reports or databases:

Much of the information is automatically provided. We have an Information System—a global IT system. It is updated with information from ongoing projects, so that we rarely need to collect data not available through the system. Then we have several forums where we meet and information from various projects is presented.

Turner and Müller (2004) describe the role of communication between project managers and middle manager and its importance for project success. They identified the information needs of middle managers, and the required communication from project managers. In further studies, they showed the cultural differences in this communication (Müller & Turner, 2004) and the impact of contract types on the quality of communication between project manager and middle manager (Müller & Turner, 2005).

Initiation of Reviews

As follow-on from the identification of bad projects (described above), middle managers often initiate project and program reviews to assess performance and develop corrective actions as needed. As stated by one of the interviewees:

I am responsible for the resource utilization of a pool of project managers. I perform periodic reviews of projects and rate the effectiveness of the project managers. I participate in project reviews at varying phases and ensure adherence to our project delivery process. I assist management in the evaluation of business cases for the portfolio.

A positive side effect of these reviews is their knowledge transfer between projects. (Kess & Haapasalo, 2002). Newell (2004) argues that reviews should be related to process and procedures, so that other projects could gain knowledge and understanding from these experiences.

Handling of Issues

Here managers engage in the identification of possible resources for problem solution. As shown above, managers in high performing organizations devote significantly more time to this role than those in low performing organizations, as an R&D manager reported in the interview:

Depending on the number of urgent corrections requested by the business side or the technical side, this is something you have to do. You put them on fast track and play down others that you now work on.

Issue handling can also comprise the removal of organizational obstacles by the middle manager, as suggested by one interviewee as follows:

…they have problems with other groups (in the firm) and things are not running smooth. Then I have to remove obstacles so they could focus on development and progress.

Jugdev and Müller (2005), in their review of project success literature, identified middle managers’ predisposition towards a project, that is, their interest in project progress, as a Key Performance Indicator (KPI) of the future. Müller (2003) showed the correlation between high performing projects and middle managers’ engagement in projects. Low performing projects were associated with little interest in project progress and associated issues-handling on the side of middle managers.

Coaching of Project Managers

Due to their seniority, middle managers often coach project managers in their work. This spans project management-related areas to the wider organizational areas, such as politics or inter-organizational relationships. A department manager reported this as follows:

Acting as a coach for the project managers and catalyst for making things going.

Englund and Müller (2004) describe a process for project managers to navigate in the political “jungle” of organizations, and how to use a project management office to foster project management work throughout the enterprise.

Improvement of Processes

All managers interviewed were involved in the improvement of their organizational processes; as such, it can be viewed as a standard role of middle managers. One manager described the scope of these improvements as:

I have to implement improvements, better measurement procedures, and stricter quality assurances.

In terms of time devoted to program and portfolio management tasks, this role ranked second after the handling of issues associated with projects or programs. Internal process improvement projects and organizational change projects have been described as especially challenging due to organizations’ inertia, that is, their resistance to change and the associated obstacles in project implementation (Blomquist & Packendorff, 1998, Blomquist & Sandström, 2004).

Summary of Managerial Implications

Organizations should adapt their governance structure to the needs of their environment and project types. Middle managers should be included in resource procurement, steering groups, and identification of bad projects and project reviews.

Middle managers’ roles in portfolio management are intertwined with traditional line management roles and, in many cases, are executed by the same person. Program management roles are not as interwoven with line management roles and, therefore, can more easily be separated out as a standalone role or position in an organization.

In order to increase the chances of an organization’s success, project-based organizations should use a hybrid structure consisting of program and portfolio management, which emphasizes:

- Handling of project-related issues

- Review of projects

- Work in steering groups

- Procurement of resources

- Identification of bad projects.

Implementation of the roles described in this chapter will allow organizations to handle the requirements stemming from the nature of their projects, the complexity of their organizations, and the need for an external, customer-oriented focus.