9

Feedback Is a Gift

Feedback is a gift.

—Lee Caraher

Why does this group need so much feedback?” asks Susan, a fifty-five-year-old hedge fund manager. “We hire the best of the best, and I still can’t believe how much feedback the under-thirties need.”

Feedback, the need and the desire for it, emerges consistently as a theme with and for Millennials. On the one hand, managers bemoan that they are constantly interrupted with requests for off-schedule check-ins to “make sure I’m on the right track.” On the other hand, managers expressed incredulity that their younger colleagues are so clueless. “Why don’t they know?” was a constant refrain in almost every conversation.

I’m going to guess that every Baby Boomer’s and GenXer’s boss said this about him sometime in the early part of his career. It’s like the pushmi-pullyu from the Doctor Dolittle stories—there exists a tension between what people ask for and what they really need, leaving managers stranded between being helpful and being perceived as a micromanager. It’s enough to send us running for the bottle. The best gift we can give our colleagues all year long is corrective and redirecting feedback in a way that can be heard to help them capitalize on the great things they’re doing and to improve on those skills on their growing edges. This is a gift that costs nothing, and when given, saves time and reduces frustration all around. In the end, feedback is a gift we give ourselves.

Not that feedback is easy to give, or to hear, at first. Like all good things, giving and receiving redirecting feedback requires practice.

Timing counts heavily in effective feedback. The key is to correct people as close as possible to the moment that it’s needed. When weeks or months pass, it can feel to the employee that the incident is ancient history dredged up to find fault. It’s also important to give feedback in a timely manner so that your frustration does not fester and grow. Tell people how they can improve as soon as you see that they need it, so that employees don’t keep on going without knowing they aren’t performing to your expectations, expectations they may not understand.

Daphne, executive director of a nationally known think tank, avoided telling her young associate that he couldn’t just decide to stroll in at 10 a.m. because, she says, “I didn’t want to seem bitchy and I figured he’d catch on after he saw that he was always the last one in the office.” She was ultimately faced with telling her younger colleague that the previous six months had not been satisfactory. She knew to expect some backlash from the young man, and indeed got it: “He said it was unfair to go so long without telling him that he was doing something that could hurt his performance review. He was right.”

They cleared the air and have moved forward with much clearer expectations of what they expect from each other. Now Daphne is trying “much harder to address things when they come up” instead of assuming that people will just notice and do the right thing.

![]()

Feedback People Need

Giving feedback is challenging for everyone. I take that back. Giving feedback that people can actually hear, absorb, and act on is challenging for everyone. It is so challenging that many managers and leaders avoid giving it, preferring to sidestep what could turn into a conflict or confrontation.

No one wants to keep doing things the wrong way. I believe everyone wants the feedback they need to be effective in their jobs. They want it even if it’s embarrassing. They want you to help them be their best. Most of all, they want input and correction delivered in a way that is respectful—a way that honors their effort to date, while offering a better, more fruitful way forward.

In Leadership and the Art of Conversation,2 which I encourage everyone to read, Kim H. Krisco explores effective ways to use conversation and language as a management tool, so people can hear and apply feedback. “If managers change the way they talk to people,” explains Krisco, “they can become much more effective managers—they can become great leaders.”3

Using Effective Language

The challenge with feedback is not only giving it, but also having it be heard. There are two language changes you can make right now to be more effective.

Strike Why Questions from Your Repertoire

Even if you don’t mean them to, “Why?” questions sound accusatory and judgmental more often than they sound open and inquisitive. With “Why?” most people hear “You’re stupid.”

- “Why did you do it that way?”

- “Why would you say that?”

- “Why are we talking about this?”

You may intend an open dialogue but you’ve set up a defensive one with the Why? question. Instead, open the conversation with affirmations first and then ask “How?” or “What?” questions that get to the matter at hand.

- “Good effort. How should we go forward?”

- “I know we had great expectations. What do you think happened? How will we avoid this in the future?”

- “That’s interesting. What do you suggest as a next step?”

- “Tell me more about what informed this decision. Let’s figure this out together.”

This has been the most challenging change I’ve tried to make in my own leadership language. I’d say I’m successful about half the time. But now, as soon as “Why?” comes out of my mouth, I’m able to adjust and reframe the question so that the person or people I’m talking with don’t immediately go on the defensive.

The Power of “And”

As Bill Gross, founder and CEO of Idealab, says, “When you start telling someone, ‘You are really great at X, but’ the but negates all the goodwill that you are building up with the first part of your sentence. The but gets someone’s defenses up, and makes them way less able to hear the important thing you want them to listen to.”4

Use “and” instead of “but,” and you can be much more successful in helping the other person hear you and achieve the goal. To do this, write out the “but” clause you’d like to use and then find a new way to get your point across with an “and” clause.

For example:

Go from: “Jean, you are great at project management, but you need to make sure you don’t laugh at people who don’t understand the task at hand.”

To: “Jean, you are great at project management, and you’d be even more effective if you would take the time to explain the task at hand to the people who don’t get it the first time.”

Of course, this is not Millennial-exclusive advice. This is language you should use with everyone. Although, if you’re predisposed to think Millennials only want positive feedback and can’t hear constructive criticism, really take this to heart.

Feedback People Ask For

Millennials get dinged for asking for feedback all the time and “then not being able to take it,” as Leo, forty-eight, says. “They don’t know how to take criticism—why do they ask for feedback if they don’t want to hear how to improve something?”

The conundrum of feedback is that there’s a disconnect between employees expecting affirming feedback and needing constructive criticism. And, of course, the way different people deliver criticism, no matter how well intentioned, can contribute to employees feeling hurt or misunderstanding the point of the critique.

“I had a woman on my staff who was constantly lurking by my office to get my attention. She’d wait during meetings or when I was on the phone. And even though we had a time to check in, she couldn’t wait because she ‘didn’t want to waste her time’ if I didn’t like what she was doing. It drove me crazy,” shares Elizabeth, fifty-two, about one of her younger colleagues. When I asked Elizabeth what she had said to her colleague to discourage this behavior she was silent, and then admitted, “Nothing.” Here’s the deal. It’s on you if you’re frustrated with behavior that you haven’t addressed with people.

Milestone Setting

When employees ask for feedback at too-frequent or inconveniently timed intervals, we need to work at weaning them from input given throughout the process and focus them on getting feedback at predetermined milestones.

We need to build in check-ins that allow enough time to fix things if the work is not ready for prime time. And we also need to transfer the work fully to our team members so that they start carrying the full load of their responsibility.

And it is a weaning process for some. That sounds maternal, I know. I don’t know a better word to describe the process. We need to meet our staff where they are, not expect them to leap beyond what they know without guidance. If we help our colleagues on their journey to where they want to go, they will be more valuable contributors to the organization and less irritating for you.

The Tough Conversations

For a variety of reasons, most people I talked with don’t like to have the hard conversations with their colleagues, partners, or clients. Some people simply hate confrontation, while others don’t want to be “the heavy,” and still others don’t want to put the time or effort into hard conversations because they believe they are a waste of time, and that the employees won’t change.

Good teams—those with a variety of like-minded and diverse points of view—address and resolve issues for everyone’s clarification and benefit. Good teams find a good, interdependent way forward after conflict and keep working on any issues over time. While I don’t think most people intend to cause conflict or frustration, it happens. We are all human.

Participating on teams effectively is hard work, and good teams should be protected at all costs; learning how to handle conflict effectively is a key skill each team member, of any age, needs to master.

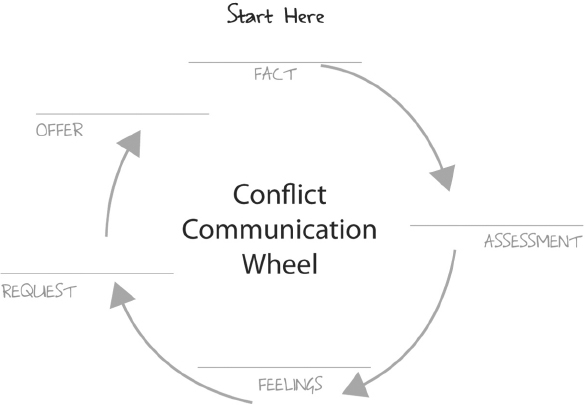

Among the many excellent tools we use at my company is the communication circle, which executive coaches Lori Ogden Moore and Susi Watson adapted based on work done at Georgetown University. By working through the communication circle, people separate facts, feelings, reasons, and blame, and are able to articulate specific requests to rectify a situation and explain how they can help the team work well. Using the communication circle also allows people to put some time between the incident that broke their frustration threshold and the conversation about it, so that they’re more equipped to reach a productive solution.

When the ship’s going down is not the time to ask why the hell someone drove into the iceberg. When there’s time to impact the outcome or after a disappointing result or event is the time to ask for a meeting to discuss what is happening or happened and how to fix it going forward.

Figure based on work done at Georgetown University by Lori Ogden Moore and Susi Watson.

The communication circle is a simple process that helps break down the parts of conflict to get to a productive collaborative agreement about how to proceed. Before the meeting, one or both of the people fill out the circle with their facts, assessments, feelings, requests, and offers. Usually the person calling the meeting goes first, walking the other person through their circle. Then the other person has a chance to respond to the assessments, requests, and offers and/or goes through their own circle. Together the two (or more) people agree on a way forward in the spirit of improving outcomes, processes and/or team dynamics.

Step 1—Facts: Start with the facts on which everyone can agree.

“The document was late.”

Step 2—Assessment: Articulate your assessment of why these facts are true.

“My assessment is that you waited to start the work until the deadline was near, underestimated how long it would take, and got stuck balancing it with the rest of your work.”

Step 3—Feelings: State your feelings about the situation. Do not skip this step! Feelings are important so that people can better understand your point of view.

“I feel angry that you left me hanging and I had to stay late to make sure the document was completed on time so it could be included in the report to the board.”

Step 4—Request: Make the request that will prevent the fact from happening again.

“My request is that you deliver this document a day earlier next month, and that you let me know at least two hours ahead of time if it looks like you’re not going to be able to make the deadline. That way, I can help you or reprioritize your workload so you can get this important document done.”

Step 5—Offer: Make an offer to the other person of how you can help him avoid the situation in the future.

“My offer to you is to check in with you first thing on the deadline day to make sure you have everything you need to get the document done.”

Finally, the other person responds to the assessment, request, and offer with agreements or alterations and/or goes through their own circle. The point is that both sides are heard and can use these steps to air grievances and solve problems together.

By walking through issues with these five steps, anyone can address an issue that is squelching performance, sowing ill will, or causing conflict among even the best of teams. Every team is going to have issues. Good teams resolve them quickly.

Generous Feedback Is a Cultural Thing

Feedback does not belong solely to the realm of management—everyone, no matter what her title or role, can provide constructive feedback. “Great job! I like the way you wrote the recommendation.” Or, “Good stuff. So that you know, you swayed a bit while you were talking. Next time, try planting your left foot a bit in front of your right foot.” Or, “I really liked what you had to say. So that you know, you slid into up-talking a bit, which made it a little harder to hear.” And one of my colleagues was brave enough to say to me, “Lee, when your eyes bug out it looks like you’re really mad.” (I’m usually not, I’m usually just thinking hard.)

The worst thing we can do to our colleagues is to let them swim in ignorance. Giving feedback—positive and negative—in a constructive manner that can be heard is the ultimate gift to your colleagues, and one that generates reciprocity.

![]()

Management Dos and Don’ts

- Do articulate your expectations for behavior, standards, and dress early on and remind people.

- Don’t sound preachy.

- Do remove “but” clauses and “Why?” questions from your vocabulary.

- Don’t assume your people were raised the same way you were and inherently know what is expected of them.

- Do give feedback in a timely manner.

- Don’t hold feedback until you can’t take it anymore.

- Do use the communication circle to help resolve issues between people or among groups.

- Do find fun ways to reinforce your expectations.

Millennials Dos and Don’ts

- Do ask what is expected of you.

- Do be open to some rules that may be new to you.

- Do pay attention to how experienced people in the group dress, address e-mails, and present themselves in meetings, and adopt their norms.

- Don’t stick out for the wrong reasons.

- Do ask, not tell, your manager before you work from home or leave early for a doctor’s appointment.

- Don’t say, “That’s too early for me” when you’re asked to show up early for an important meeting or workday.