8

Give Clear Direction

The gap between intention and execution needs to be short and shallow.

—Lee Caraher

As you provide context and color that explain why all work is meaningful work, you will also need to provide direction for the result you seek and explain how the employee or team should get there. You’ll also need to plan to give plenty of constructive and affirming feedback along the way. The result is the easiest piece of the puzzle: it’s the easiest to say and it’s also the easiest to assume that everyone understands. For that reason it’s often skipped over: “Of course everyone knows what we’re looking for in the finished product.” No statement is more false.

Direction—The Goal

While it may seem counterintuitive, when we’re articulating what we want the result to be—a document, a presentation, a meeting, a campaign—we have the perfect opportunity to solicit input and ideas from the team. “The goal is _______. How can we: Make it great? Minimize risk? Streamline it? Put something new into the mix?” You get the idea.

If you have examples from the past that serve as standards you’d like to maintain, share them. “Here’s what we’re looking for. Are there ways to improve this?”

By starting with the end in mind1 and asking for input on how to maximize that end, we dramatically increase a person or a team’s investment and buy-in, and we improve the odds that we’ll get what we’re looking for.

Direction—“How We Get There”

The “how we get there” part of the equation is harder to manage than the articulation of the goal. You probably have a good idea of how you’d like the different parts of the project done. Resist the urge to prescribe exactly how you think things should be done before soliciting input from the people who need to do the work.

Maybe no one will say anything and you’ll get a blank stare when you ask, “How would you like to approach this?” Maybe you’ll get a long, complicated answer that you think will send the person down several rabbit holes. Maybe you’ll get exactly what you think should be done. Maybe you’ll get a better idea than you’ve ever thought of. The important thing is that you’ve asked the question. Be open to whatever you get back.

- If you ask how you think the project should proceed and you get nothing, take a deep breath and say something like: “Okay, why don’t you approach it this way, and the next time you might have some suggestions on how to improve the process.”

- If you get what you think is a half-brained idea, look at it as an opportunity to coach the person through the project and relevant milestones. Use phrases like, “Let’s take a look at that—how would that work?” or “Cool. How can we streamline that?” And then coach the employee to a productive way forward.

- If you get a better idea (be willing to hear that!), respond with “Great idea, let’s set up some check-ins so we can make sure we stay on track.”

Drive Out Ambiguity

Our business lexicon is full of ambiguity we don’t recognize, maybe because older workers have a different understanding of the vocabulary.

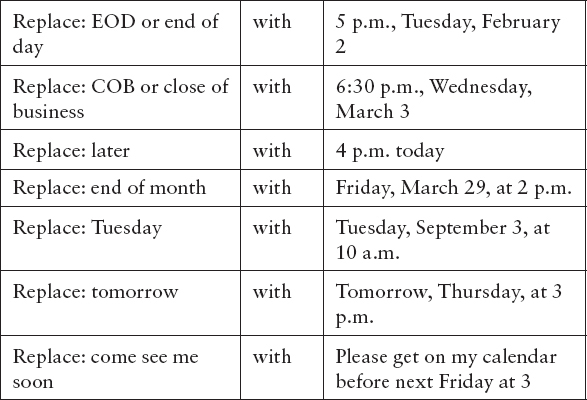

While it might seem illogical setting deadlines is one of the most common places we find ambiguity in the workplace. Deadlines? Yes, deadlines. When is end of day? Or close of business? Or tomorrow? When is the end of the month? Later? Tuesday? Never. They are never. Whose day? Whose business? In what time zone? Until 11:59 p.m.? At 11:59 p.m. on the last day of the month, even if it’s a Sunday? Tuesday—which one? And later never gets here … ever. As my mother used to say, “I said March; I didn’t say which year.”

You may feel you’ve given very clear deadlines that can’t be misinterpreted, but unless you give a great deal of specificity, your team can disappoint you and be right … and nothing is more maddening.

In the end, the gap between intention and implementation needs to be short and shallow—and it’s your job to describe your intentions with so much clarity that other people can implement to your expectations … the first time.

The Time Warp

One of the surprising elements I found in the interviews I conducted for this book concerned Millennials’ different sense of time. “They have no sense of time,” complained people under and over 34 years old.

Managers commented that Millennials “didn’t spend enough time to do the job well,” while Millennials consistently declared that they could “get the job done so much faster” than their managers. Here, dialogue and guidelines help everyone understand the changing work flows occurring today.

Managers, I encourage you to give estimated time required to finish the project well, and to add, “you may find a faster way to get this done. What I care about most is that the project is done well.” Give a clear time guideline while acknowledging that the other person may know shortcuts that won’t affect the quality of the work. Here’s a great opportunity for managers to learn from younger colleagues. Many times I’ve learned shortcuts that didn’t impact the quality of the work that my younger colleagues applied once they tackled the task.

The discussion about the time frame of the work also provides a forum for feedback if what comes back does not fit the bill. If that’s what happens, you can probe how the employee approached the work and pinpoint where shortcuts were taken without an appreciation for how they might impact the quality of the work. In the dialogue you have you’ll be able to reinforce the quality message and discuss what shortcuts or workarounds can be made that don’t impact the final product—you may even learn a new way to cut thirty minutes from your own work flow.

Millennials, I urge you to listen to the guidelines and follow them … at least the first time. Once you complete an assignment as it’s been outlined by your manager, you’ll be able to see the whole picture. Then you’ll be able to improve on it and get the same or a better result, and your way will have a better chance of being appreciated and adopted.

Deadline Specificity

When giving deadlines, be specific: provide exact times on exact dates.

Examples:

This level of granularity can’t be misconstrued. If you provide this type of specificity and your employee or team misses deadlines, it’s not a matter of misunderstood expectations.

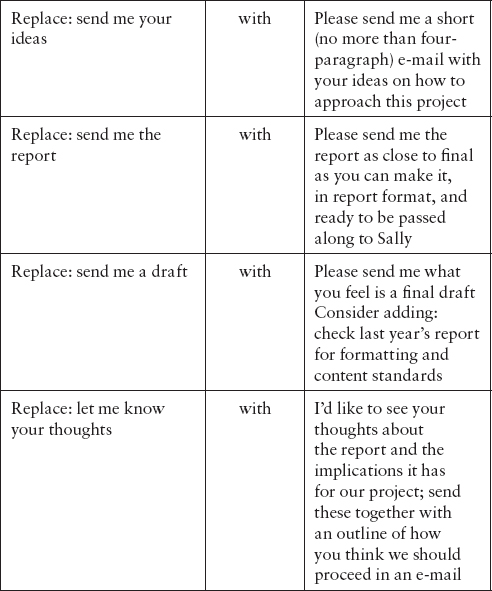

Formats and Condition/Status

“I never would have dreamed of sending an unfinished product to my boss,” says Dan, forty-five. “And now all I ever get are half-assed efforts that I need to totally rewrite to get them done—it’d be faster and easier for me to do the work myself.”

It’s not enough to say, “Please send me the report by Tuesday, September 3 at 10 a.m.”

In interview after interview, managers across the country in different industries described getting work product with loose outlines instead of fully formed ideas, reports, or recommendations ready for distribution. They also complained that they were submitted drafts that were full of inaccuracies, typos, or messy language.

“When I tell people that their work isn’t done I often get, ‘You didn’t say you wanted it to be final’ or ‘I thought you would just fix any problems.’ How is this even a possibility?” says Michelle, forty-three.

It may seem incredible, but in order to get what you want, you need to articulate exactly what you want in your instructions. Always. Do not assume that the other person knows what you mean or holds the same expectation of delivery that you do. Ambiguity is in the eye of the beholder. As long as someone else can say, “I thought you meant” or “I didn’t know that” and be right, you are rolling the dice on the work submitted to you.

Replace:

Revisions

If you get work full of typos and loose language, send it back and tell the person it’s not ready to be reviewed.

Hi Tim,

You must have sent me the wrong version. Please take a look and make sure that the report [e-mail/memo] is typo free, is in the standard format, uses tight, active language, and is something that I can pass along to Sally. Please send this to me by tomorrow, Tuesday, at 10 a.m.

Thanks,

Peter

If this has happened before, respond with something like:

Hi Tim,

This version is not ready for me to review. Please take a look and make sure you’ve got all of the information you need and that the document is correctly formatted, free of typos, and uses active language and concise sentence structure. I expect this back to me by tomorrow, Tuesday, at 10 a.m.

Thanks,

Peter

And a third time (please, no):

Hi Tim,

This is not ready for me to review. Please take a look at my last e-mail and make sure you follow all of the direction there. Please see me by 5 p.m. today to check in on your status.

Thanks,

Peter

Or

Quality

Another common complaint about the way Millennials work concerns the quality of the thinking or work process. “They think the first answer they find with a simple Google search is the answer and sufficient to base a recommendation on,” says Nancy, fifty. Or, as Perry, fifty-two, adds, “They just want to get things off their list so they can move onto the next thing. They don’t seem to care whether it’s done right or well.”

First of all, we all know that less-than-quality work is not the hallmark of Millennials alone—it’s common to people from all generations who either (A) don’t know what quality is or (B) don’t care what quality is. Until you’ve proved that A is not true, don’t move onto B. Schooled to ace the test and not necessarily master the material, Millennials may never have been shown or taught how to vet sources and assemble an informed point of view from a variety of good sources.

While I love Googling as much as the next person, the phrase “Just Google it” is as grating as fingernails on a chalkboard to me. We can prove over and over again that where the first link takes us or what is on the first page of any search result is most likely not enough to create a well-informed understanding of a subject (unless, perhaps, the search is on Justin Bieber).

For anyone new to your organization or team, it’s important to set the tone and provide guidelines for the quality of work you expect before they start. Don’t waste time—yours or theirs—assuming they will know what you expect. Spend ten minutes before someone starts on a project to describe the quality of the work you expect if you want to raise your odds of receiving the quality of work you expect.

While it may seem obvious to you, one person’s full analysis is another person’s snapshot. Be as specific as possible.

For example:

- Identify any sources you want to make sure are included.

- How would you characterize the work—in-depth? Top-line? Snapshot?

- Do you need to have a certain number of sources? Top one hundred? Ten?

- Do you have an example of good previous work you can share to give context?

Replace—“I need a full analysis of last quarter’s sales” with “I need a full analysis of last quarter’s sales by customer, salesperson, product, and price point. Please take a look at the last two quarters as a comparison and identify any trends. I’ll look forward to your assessment of any opportunities you think we have. I think this may take four hours.”

And once your employee gets it, you can say, “Great job last time, can you please do the same thing and bring any learnings forward this month?”

Use E-mail to Your Advantage

E-mail is hell. It’s a hell of redundant messages, most of which are required to get the point across because the originator did not provide enough context, specificity, or instructions in the first e-mail.

The point of communication is to deliver a concept that can be well understood by the recipient. We’ve all gotten lazy with e-mail. Based on e-mail patterns in my inbox, I believe we can reduce e-mail volume by more than 55 percent if we drive ambiguity out of e-mail.

To: Lee

From: Joe

Cc: Quail Team

RE: RE: Meeting on Caller Project Progress

Date: Monday, June 2, 2012 3:15 p.m.

Lee,

I’m available anytime on Wednesday or Thursday. Do you want everyone to report on his or her responsibilities or a topline? Do you want a PowerPoint? Who should drive that? What do you want to see before the meeting?

Thanks,

Joe

To: Lee

From: Liam

Cc: Quail Team

RE: RE: Meeting on Caller Project Progress

Date: Monday, June 2, 2012 3:16 p.m.

Lee,

I can meet on Thursday. Do you want the whole team there? I’m not sure everyone is here next week. What format? Any key metrics you’re looking for? What’s the outcome you’re looking for?

Thanks,

Liam

And so on.

It’s enough to send you into a fetal position under your desk once your hand’s been wrapped in a cast for carpal tunnel syndrome due to so much unnecessary typing.

To avoid unnecessary back-and-forth, drive as much clarity as possible into the first e-mail. Provide context, name exactly who is responsible for what, give deadlines, and provide opportunity for the team to bring to your attention items you haven’t considered or heard about. If you’re using a global e-mail list, call out specific people who have action items—don’t assume people will know they’re supposed to do anything.

To: Joe; Sally

Cc: Quail Team

From: Lee

Re: Meeting on Caller Project Progress

Date: Monday, June 2, 2012 3:14 p.m.

Quail team,

I’d like to meet for a progress check-in on the Caller Project next week either Wednesday at 2 or Thursday at 10—Jane will confirm with you.

Joe and Sally, please take the lead on this with input from the rest of the team. I’d like to see overall status of the project elements with special attention to the Community Plan and Packaging. If there are any other elements that are in yellow or red, please bring those forward as well. Anything on schedule without issues need not be discussed during the meeting. PowerPoint will be best. I’d like to see the report by 6 p.m. the night before—Jane will confirm deadline with you.

Thanks,

Lee

While e-mail is great for keeping track of (sometimes inane) conversations, we get lazy quickly in our effort to plow through it all. And in that laziness we increase the chance of details being lost—important details such as deadlines, formats, or other requirements.

Drive ambiguity out of your e-mail strings by striking the following from your e-mail vocabulary: Start reading at the bottom. Never start an e-mail with “Read from the bottom”—you are just inviting confusion. Bring all of the key facts forward in your reply so that in one screen everyone can see the scope, deadlines, context, and responsibilities.

E-Mail Dos and Don’ts:

- Do provide as much of the desired result as possible in your e-mail: deadlines, responsibilities, and context.

- Do name specific people’s tasks if you’re using a global list, so that person knows he has something to do.

- Don’t assume everyone will be able to keep track of all of the details in a long e-mail string.

- Do bring the details to the top of an e-mail string.

- Don’t require people to “start at the bottom” to get all the details, deadlines, and requirements.

Clarify Assumptions from the Start

Whoever said assumptions make an “ass out of U and me” was a genius. A true genius. For management and Millennials alike, assumptions about an event, project, or rule often mean that the two groups end up on polar ends of the spectrum of understanding.

Management: “I assumed they knew what I was talking about.”

Millennial: “I assume they will help me do the job”

Management: “I assume they know what is expected.”

Millennial: “I assume they will tell me what they want and will give me the tools to do it.”

Management: “I assume everyone just needs to do their job.”

Millennials: “I assume you’ll tell me how my job fits in with the rest of the teams’.”

Lots of assumptions. And too often we learn that our assumptions diverged before the project even started, though we didn’t realize that until after we’d executed a plan to less than satisfactory results.

Why does this happen? Because we don’t voice our assumptions. We all need to get better at thinking about and articulating our assumptions before we start our work. In chapter 4 I talked about how important context is for Millennials—and the rest of us—to effectively engage in the work at hand. A big part of context are assumptions—those factors we take for granted as fact or commonly held (yet unarticulated) beliefs. Beyond the purpose of the project and individual roles in it, take the time to articulate your assumptions and solicit your team members’ assumptions as well.

For example:

- How long do you expect the work to take?

- What do you expect people to do if they hit a roadblock?

- What is the desired outcome? How should it look?

- What are the check ins?

- When do you need to have people in the office? By when?

And so on.

What does your team expect? Ask them!

- What do you think you need to succeed?

- What do you think the outcome will be?

- What kind of impact can we make?

- What’s the competition going to do?

And so on.

What happens when things go awry? Too often if we actually take the time to review a project—what went well and what did not, we ignore assumptions that each team member carried into the assignment. And by ignoring them you’re stacking the deck against making the kind of exponential difference you want to make the next time you try.

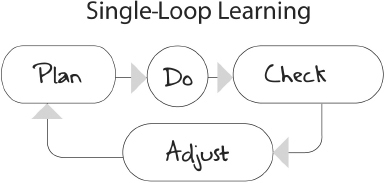

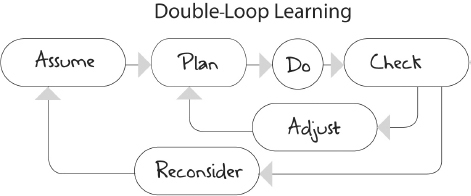

A good step to take when examining a work plan’s results or process breakdown is to examine the results you got, examine how closely you adhered to the plan (what got in the way or changed) then adjust the plan based only on what happened. If your team does this single-loop process Plan-Do-Adjust, you will be ahead of most teams, but chances are high that you will only be incrementalizing your way forward.

With Single-Loop learning,2 there’s a real danger of repeating ourselves without getting to the root of why we’re disappointed with the results or the process. A better, no great, step to actually fundamentally improving outcomes and processes is to incorporate Double-Loop learning when examining project results. Double-Loop learning puts into the process the step that allows us to align on the assumptions we held going into the project: assumptions about the market and the competition, as well as the assumptions about who’s going to do what, deadlines and dependencies.

By articulating assumptions at the beginning, you will drive ambiguity out at the start of a project. By looping back to the assumptions, not just adjusting the plan, after completing a project, you will be able to plan better for ongoing work.

This is how teams get better together, become more efficient, and get better results: by aligning their assumptions, driving out ambiguity, and continually revisiting the assumptions to ensure that everyone’s pulling the oars in the same direction. And when your team includes people from different generations, double-loop learning gets everyone on the same page quickly and without ambiguity.

Checking back in with the team on process and improvements is not a sign of weakness or pandering. It is the hallmark of good leadership. By consistently driving double-loop learning into the project management, to continually reaffirm or challenge the assumptions everyone is working from, everyone can learn how to drive efficiency into group dynamics.

By being as clear as possible in your direction, you are setting an example for how thoroughly you want your team to work and how the team members can support one other in their interdependent work.

Give Direction Early and Often

I work in San Francisco, a city that attracts people from all over the world. We come together, with our different cultures and different upbringings, and bring our different perspectives together. No wonder we have issues “standardizing” expectations of behavior. And this is true throughout the country—people I talked with in the Northeast, Northwest, Midwest, South, and Southwest all talked about the same phenomenon.

So how can we get everyone on the same page without feeling like micromanagers? Start early, repeat often, and find fun ways to reinforce standards.

Onboarding is the first in-depth opportunity you have to convey your expectations. During the onboarding process, it’s critical that new employees understand their own role, their team’s purpose, and how they and the team fit into the company’s vision and mission, but it’s also crucial that they understand the cultural and practical expectations of how a team or company works.

Some of the key questions/topics you should start clarifying from day one are outlined here. As you will see there are many different ways to answer these standard questions – the more clarity you can drive into the answers, the better off you will be setting clear expectations for everyone from the beginning.

What are your expectations for office hours? Choose what makes sense for you.

- Everyone has the same hours?

- Normal arrival time is between 7:30 and 9 a.m., and if you’re going to be later than that you need to let your team know. OR

- Normal arrival is by 10 a.m., and departure by 9 p.m.

- You can work from home when it works for the team, but remote work needs to be approved beforehand. OR

- You can work from home whenever you like. OR

- You can’t work from home.

- Doctor and dental appointments can be scheduled throughout the day, but you need to ask if the schedule works for the team and the work at hand. If not, you need to reschedule unless it’s an emergency.

How do you approach conference calls and meetings?

- Arrive five minutes early.

- Always have an agenda.

- If people on the team are in different places for a call and the team is talking with someone outside the organization, everyone is on IM, so you can coordinate answers.

- Never leave a meeting or conference call without clearly defined next steps.

- Always send an e-mail/memo summarizing the decisions made and next steps.

- Everyone goes to every meeting. OR

- You may not attend everything — the team leader will decide if you attend or not.

- Leave cell phones off or muted.

- Don’t look at cell phones or e-mail during meetings or calls.

What are office norms?

- If you’re sick we expect you to stay home. AND

- If you’re sick, please notify your manager and the office manager as soon as possible by e-mail.

- Everyone takes their dishes to the kitchen and puts them in the dishwasher. OR

- No one leaves dirty plates at their desk. OR

- The office manager will come by and pick up your dirty dishes.

- Staff meetings are attended by all, so no scheduling outside meetings during staff meetings, unless the matter is urgent.

- Use your office phone for company calls and personal calls that aren’t too personal. OR

- Take your personal calls behind closed doors—what’s personal is personal.

- Don’t leave your medication out for everyone to see.

Is there a dress code?

- You may wear whatever you want as long as it’s clean and covers your privates. OR

- We are business casual—that means jeans are welcome as long as they don’t have holes, frays, or are cut/hang so low that your underwear or tattoo shows (no matter how cool that is). Yes, I know those jeans are your most expensive ones. Yes, I know you spent painstaking hours distressing them perfectly. No, they’re still not okay. OR

- We dress in business attire at the office. That means suits and ties for men, and suits or professional coordinates for women.

- No open-toed shoes. OR

- Any clean shoes except flip flops or Lucite stilettos.

- Casual Friday—no jeans. OR

- Casual Friday—jeans allowed.

- No bare midriffs or exposed backs.

- Tattoos are okay except on the face. OR

- Cover all tattoos.

- No skirts shorter than two inches above the knee. Or four inches above the knee.

- No perfume.

The company dress code should not be a surprise to a new employee. This should be covered in the recruiting process.

What are the expectations for dinner with the big cheese, a client, or another external partner?

- Seating will be specified by the team leader.

- Put your napkin in your lap when you sit down.

- Silence your phone and don’t look at or answer it at the table.

- Don’t have more than two drinks. OR

- Have one drink less than our guests or the boss.

- Wait for everyone to be served before you start eating.

- The team leader will pick up the check.

- Do not brush your hair or apply lipstick at the table.

![]()

What is the office e-mail etiquette?

- Always use a subject header.

- Always spell check before you send.

- Turn on send delay to five minutes so you can retrieve something if you need to.

- People who have something to do go in the “To” line; everyone else goes into the “cc” line.

- Reply to all e-mail within two hours. Four hours. Twenty-four hours. (Everyone needs this type of guideline, with whatever time frame makes sense for the organization—truly, everyone does.)

- If you’re not in the “To:” line, don’t reply unless you have pertinent information that will help the person or people in the “To:” line.

- Turn on your auto-reply out-of-office message if you’re going to be out for more than four hours. OR

- Never turn on your auto-reply message.

Reinforcing Expectations

At my company, we found that everyone had a different definition of business casual and a different understanding of dining etiquette, as well as varying expectations about other conduct. We began covering these topics in the onboarding process, but found that people benefited from being reminded from time to time.

Games

To reinforce expectations, consider putting the company’s expectations about conduct into a game show format à la Jeopardy or Family Feud.

Etiquette Jeopardy. Fill a wall with your team’s etiquette guidelines, grouping them under different categories. Divide the group into teams; use an Eggspert buzzer to let people buzz in to answer questions.

Player: “I’ll take Conference Calls for two hundred.”

Moderator: “The answer is five minutes.”

First player to buzz: “What is ‘How many minutes early should we dial into a conference call’?”

Etiquette Family Feud. Divide the team into two sides. Rank the guidelines by priority of importance, and assign numerical value so that total number of priority points is one hundred (for example: “Call in five minutes early” is twenty-four points, “Always have an agenda” is twenty, “Turn off cell phones” is nineteen, etc.) Use an Eggspert buzzer to let people buzz in.

Moderator: Name something that is important for conference calls.

First player to buzz: Always have an agenda

Moderator says: Let’s see “Have an agenda!” Survey says, twenty!

The winning team gets lunch or drinks or some other fun reward. It’s dorky, but fun, and it gets everyone involved. Everyone gets some reinforcement out of this kind of game, and you’ve had some fun to boot.

Reference Guides

While I think it’s true that everyone could benefit from a quarterly browse through Emily Post’s The Etiquette Advantage in Business,3 that three-inch-thick hardback book is cumbersome and expensive to put on everyone’s desk—and it’s bound to get put out of sight, never to see the light of day. If you happen to have a copy, browse it every once in a while. (Tip: It’s a great gift for college students. They may look at you askance, but it’ll be well worth the rolled eyes.)

Staff Reminders

Once every two months or so, choose one business etiquette topic and review the guidelines for that topic at your staff meeting. It’ll take five minutes and serve as a good reminder for everyone.

Every two months or so, send an e-mail reviewing the guidelines or clarifying any misapprehensions that may have arisen.

1. EverythingSpeaks Desktop Guide. To make it easier to keep manners top of mind after orientation, I created EverythingSpeaks, a desktop guide to manners. It’s a Lucite box of colorful cards that sits on people’s desks. Each card has a different piece of office protocol, written with humor (I hope) and featuring an illustration that helps make the point. Categories include: first impressions, conference calls, dining out, and so on. This way we can just pull a card for a category we want to reinforce and use them as reminders without being intimidating or preachy.

It’s a lot to cover, but all guidelines for expected conduct need to be described, and in some detail. Don’t let people’s inappropriate behavior make you crazy and build bad impressions of themselves or your company when they probably just don’t know better—really, they probably don’t know better.

Management Dos and Don’ts

- Do provide exact times, dates, and required formats or guidelines when giving deadlines.

- Do be explicit and reiterate expectations.

- Don’t use ambiguous terms such “end of day” “close of business” or “later” when giving deadlines.

- Do give time estimates for work, but be open to hearing about ways to do the tasks faster.

- Don’t accept work that is not completed to your satisfaction; give it back with clear instruction.

- Do tell your employee it’s good work when it is good work

- Do articulate your assumptions to the whole team before a project starts.

- Do ask what everyone’s assumptions and expectations are—regarding their own work and that of others—before you start a project.

- Do make sure that everyone understands how her work impacts the rest of the team’s.

Millennial Dos and Don’ts

- Do ask for clarification when you don’t have specific instruction.

- Don’t start until you know what’s expected from you.

- Do ask for specific deadlines so that you know exactly when something is due.

- Do ask how long things should take; if you’re done early review the instructions one more time to make sure you have completed the project (run spell check!).

- Do ask for sample work to use as a guideline.

- Do show your older colleagues how you shaved time off the project—they will appreciate it!

- Do things your manager’s way first—and then improve it

- Do let people know if you’re not getting the expected results as soon as you know so the team can revisit assumptions with this new data.