3

The Millennial Mind-Set

Millennials don’t all come from the same mold.

We’re all different; we all have different styles to achieve greatness!

—Petra, age twenty-six

Millennials were raised in an entirely different ecosystem than their parents and grandparents. Not just surrounded by, but assisted by technology and all of the advances and advantages (or disadvantages depending on your point of view) that technology brought to entertainment, education, and communication, Millennials share many traits and characteristics their older colleagues do not understand or appreciate.

Of course Gen Y interprets the characteristics a bit differently. Not surprisingly, in more than one hundred interviews and surveys with people age twenty-two to thirty around the country, I found that Millennials object to the bad rap their generation gets.

“I see evidence of what people are talking about with some people my age, but I don’t think it’s fair that a few bad examples are making us all look bad,” said Erin, twenty-four. “And I can give you lots of examples of slacker Gen Xers and Boomers in my office, and no one is saying those generations suck.” Liz, thirty, adds, “A bad work ethic is a bad work ethic, not a generational thing.”

Let’s put this into perspective. While in the last few years, article after article has derided all Millennials as entitled and needy, it’s been challenging for most college graduates to get jobs. So while this huge generation pumps out more and more debt-ridden college-educated adults eager to start their lives, the economy hasn’t been able to suck them up fast enough.

In addition, many Boomers and Xers have either stalled in their careers with little upward movement in the last six years or have extended their careers to earn enough to retire on, further narrowing opportunity for younger people to advance or new people to enter the workforce. Also, since 2008, a huge cohort of Boomers and late Xers who lost their jobs in the Great Recession have not been able to find comparable new jobs, and have effectively been displaced to involuntary retirement, significantly reduced employment and/or replaced by younger, cheaper labor.

So we have a bit of a catch-22: Millennials who have been raised or influenced by peers to believe in themselves and their ability to do anything have entered, or tried to enter, the job market just as the economy had no place to put them. At the same time, economic conditions required older workers to reset their expectations. No wonder Millennials are collectively labeled “entitled”—frankly, it’s a little too convenient.

How Millennials See Themselves

In contrast to how Millennials have been portrayed by countless articles, blog posts, comments, YouTube videos and even Saturday Night Live skits, Millennials have a vastly different point of view about themselves and their generation.

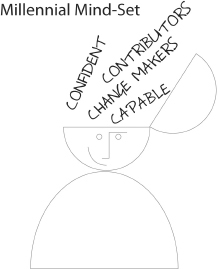

Capable

Throughout all of the interviews, e-mails, tweets, posts, updates, and blog comments, what comes through loud and clear is how capable members of this generation believe they are. “I don’t think my generation believed so much in our ability as this one does,” says Abby, forty-eight, commenting on the Gen Y members of her team. (Of course, we don’t know what early Boomers and their predecessors thought of us, but I’d guess the same thing!)

“I can get a lot more done than the older people in my office can,” says Michelle. “I may be the youngest one in the office, but I’m the most productive one.” Summing up the disconnect, Liam, twenty-six, comments, “Management underestimates my ability because of my lack of experience all the time.”

Sally, a longtime recruiter, describes a great generational gap between Millennials and the earlier Gen Xers and Boomers: “Every younger candidate I’ve ever talked with in the last five years thinks they are full of potential, and have so much to contribute right now. It’s not a question of whether or not they are right for the job, it’s a question of is the job right for them. This is so different from where the Gen Xers and Boomers were when they were at this age.”

Contributors

Importantly, and sometimes frustratingly for their managers, Millennials want to contribute to the “real” work from day one, and do not relish the idea of working their way up the ladder, a process Boomers and Gen Xers considered the norm. “I am here to make a difference,” says Michelle. “If I see a way to make something better, I will.”

When her candidates are dissatisfied at jobs, explains Leslie, thirty-two, a recruiter who places many Millennials in positions across the country, “It’s because they feel like they are caged in a confining box with no opportunity to do anything different.” In fact, many Millennials prefer going to smaller companies where they will be able to have a bigger impact and a hands-on role. “I chose to work at a smaller company so that I can wear a lot more hats, and get a lot more exposure to different functions and jobs,” says Katherine, twenty-five. “It helps me hone different skills.”

This desire for important work is a key driver for Millennials, who have been pegged as job-hoppers. While 91 percent of Millennials expect to stay in their jobs for less than three years,1 younger employees, like their older counterparts, stay longer when they understand how they fit in and how their work contributes. “I always want to feel that what I’m doing in my work is important,” says Lisa, twenty-seven, who has changed jobs three times in four years. When I asked her to explain why she had moved so many times, she described positions that “looked good from the outside” but were full of menial work. “No one told me why what I was doing mattered,” so she kept searching until she found a position where she felt like her work mattered.

Change Makers

Beyond feeling capable and wanting to contribute, most of the working Millennials I surveyed feel emboldened and empowered to change the world, or at least their corner of it. Twentysomething after twentysomething expressed a strong desire to change the way business works. “I think that Millennials are more entrepreneurial and are pushing the envelope in changing business,” says Abby, twenty-six. “We’re helping to mold and change how business is done for the better.” Abby’s sentiment was echoed over and over again by her peers across the country.

Many, many Gen Yers talked about their desire to change the world for the better through their work and/or their employer’s dedication to volunteerism and community service. Today, a company’s allowances for volunteerism and dedicated workdays for team volunteer efforts factor importantly in many Millennials’ decisions to apply to or accept positions. “I want to help effect change in my community,” says Madison. “I’m so excited about my new job, because I am part of the change that is happening in the office and in the community. It’s one of the reasons why I wanted to work here.”

A 2012 talent report reveals that “employees who say they have the opportunity to make a direct social and environmental impact through their job reported higher satisfaction levels than those who don’t.”2 When college students were queried on whether or not they’d be willing to take a 15 percent pay cut, 35 percent said they would if it meant working for a company committed to CSR (corporate social responsibility), 45 percent said yes, “for a job that makes a social or environmental impact,” and 58 percent said yes, if they could work for an “organization with values like my own.” Of course, most of these students are not in the job market and probably haven’t started paying rent yet, however it’s important to understand these factors as college graduates apply for work in our organizations.

Confident

What is crystal clear from all my discussions with older leaders and managers, Millennial workers, Millennial managers and leaders, and even Millennials who have yet to find work is that this generation is confident. They are confident that they can contribute. They are confident in their ability to learn. They are confident that they can make a difference at work and in the world around them now. They are confident that they matter. And they are confident that they can be fulfilled in their work as part of a meaningful life.

Along with this confidence comes a set of expectations and norms they feel are reasonable. Why? Some have learned from their parents—perhaps by how they were raised, with high level of parent involvement in their achievement, or perhaps in reaction to their parents’ careers. Others have learned it from their peers at college, the great petri dish for young people evolving from hormonal teenagers into adults.

In the end, it doesn’t really matter why. What matters is that we understand what our younger colleagues in the office want so that we can not only harness the energy, brain power, and technology-enabled know-how they bring to the table, but also set a new normal for work rules from which everyone—everyone—can benefit.

I’m not suggesting that we need to give the younger contingent everything they want. Catering to is not caving if it works for everyone and improves the outcome. However, we can adjust the way we approach the work environment, opportunity development, and work processes to help ensure a more forward-looking, future-proof workplace. To do this, we need to stop letting the pervasive myths about Millennials get in our way of seeing potential for productive change.

What Millennials Want

All people want to be happy in their work. “I am in charge of my own happiness,” sums up Liz. “And a big part of that is being happy in my work.” Emily, twenty-four, articulates the sentiment in a nutshell: “I’m going to be spending more time at work than on any other activity, and so if I’m going to have a happy life, I need to have a happy workday.”

Don’t we all!

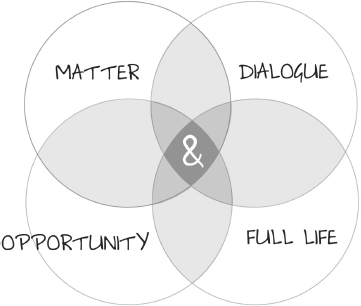

Millennials Want to Matter

Millennials want to matter in the workplace: they want their work to matter, their opinions to matter, their presence to make a meaningful difference, and they want to be part of an “awesome” team.

They want meaningful work. “It’s important to me and my friends that we’re doing something important for the company,” says Charles, twenty-four, an assistant product manager in Chicago, echoing a strong notion that was repeated consistently by Millennials I talked with in different jobs and different industries across the country. While Baby Boomers and Gen Xers may have just done the work assigned to them early in their careers without question, do not expect Millennials to fall in line this way. “ ‘Because I said to’ doesn’t work for me,” says Liz. “I need to understand how the work I’m doing matters.”

They want to be heard. Participating and not just biding time until their point of view and ideas are welcome later in their careers is key for this generation. Unlike their older colleagues, who may have expected to hold their tongues and do what was asked of them, Millennials not only want to be heard but expect that their ideas will be taken seriously. “I would make suggestions about how to streamline the work and I was told that I wasn’t allowed to give input on how the work would happen—I had to get out of there,” says David, twenty-six.

Twenty-seven-year-old Jeff, the New York-based marketing associate, enjoys his current position in part because he’s invited to comment and suggest alternatives. “My manager and her manager always ask for my opinion. My suggestions may not always be taken, but they explain why—I feel like my ideas make a difference, which is cool.”

They want to be part of a great team. While Millennials often get pegged for being a “Me” generation, I found that being part of a great team ranked quite high on their priority scale. “Being part of a team with great camaraderie is much more important to me than just the work,” says Grace, twenty-seven, a marketing manager at a large national apparel retailer. First, it makes the day better, but more importantly, it “could pay off later if people leave and are looking for people at their new job.”

Being part of a good team is “super important,” explains Amy, twenty-five, who did considerable due diligence on the team she’d be working with before accepting any interviews in her last job search. “I learned after two jobs that I needed to interview with the team I’m going to work with, so I could get a sense of the group and if it would be a good fit,” she says. “The people around me are really important—if I’m not happy with the people around me, I’m not going to be happy at work.”

Millennials Want Constant Dialogue

Perhaps because they’ve had so much digital communication and interaction and parental guidance (or interference, depending on your point of view) in their lives, Millennials expect, and seem to require, constant dialogue about their work. There is a way to channel the chatter!

They want appreciation and acknowledgement. Nothing is worse than not being noticed. It’s important that senior leadership “acknowledge what we’re doing here matters to them,” articulates Gabe. Carla, twenty-six, acknowledges that the “trophy syndrome” for showing up is an issue, and posits that we need to find a happy medium. “A generational problem for my generation is that everyone has to win. It’s a given that everyone wins. But someone has to be first, which is a hard thing to get used to” in the workplace. At the same time, “just because someone is first doesn’t mean that the rest of the team doesn’t matter too.”

They want feedback. Millennials expect, and indeed crave, constant constructive (read positive) feedback loops. I have pages and pages of comments from the Gen Yers I talked with about the quality and the frequency of feedback—or the lack thereof—about their work and roles.

“I think I have reasonable expectations of a boss,” says Liz. She believes a manager is there to “help and guide,” “listen to and hear,” and “to give feedback.” “Unfortunately, lots of managers don’t know how to, or don’t bother to, give feedback,” says Liz.

When talking about why she left a seemingly plum position, Julia placed a large weight on the lack of feedback she got from her managers. “I never got feedback on what I could improve, even though I asked for it. And then in my review more than a year into the job, I was told that I didn’t have a good enough poker face and that I wasn’t concise enough in e-mails. What? They couldn’t tell me this beforehand so I could work on it?”

(For anyone thinking, “But they can’t hear constructive criticism,” more on that later in chapter 9.)

They want transparency. Senior managers sometimes act “like we can’t find things out about the company without them,” says Drew, twenty-six. “If they want to earn our respect, management needs to tell us what’s going on before we find out from people outside the company or from the media.”

Millennials Want a Full-Life Approach to Work

Millennials were raised in the 90s and 2000s when the quest for work–life balance dominated career discussion. They watched and listened to their working parent or parents struggle to succeed at work and at home, and most likely make sacrifices in both to accommodate both roles. They’ve seen what can be achieved and don’t believe they need to wait to simultaneously have both a full career and full life.

They want freedom. Two distinct groups emerged in my research. The first group, what I call the Digital Freedom Crusaders, doesn’t place much value on being in the office at specific times. “You don’t need to know where I am as long as I’m doing the work,” says Andrea, twenty-eight. “I am more productive at home, and I should be able to work from Starbucks if I want to as long as I’m getting my work done well.” This group seems almost “bitter about having to be in the office,” says Susan the early Gen X senior executive in Minneapolis, all of whose customers/clients are under thirty-four.

I call the other group the Office Traditionalists, and they value office hours and being together, and believe that being seen matters for advancement and participation. “I like to be in the office. I have a better thumb on the pulse of what is going on, and I’ve been able to jump on opportunities because I’m there when they come up,” explains Mary, twenty-five.

Katherine, twenty-eight, adds, “My old company, a big accounting firm, had lots of flexibility initiatives—but there’s only so much you can do in a system with so many people before it broke down.”

They want work–life balance. The cry for work–life balance that has emerged in the last twenty years, first from working mothers and now from a growing contingent of working fathers, has had a big impact on the children of the people who started the conversation. “I want to enjoy my life more than my parents did or still do, and I think I should be able to now and not wait for retirement to really live my life,” says Sarah, twenty-four.

Across the board, older managers and senior leaders noted that Millennials are demanding work–life balance from the beginning of their careers. “Another thing I find interesting in a refreshing way is that Millennials are less willing to compromise on work–life tradeoffs than my peers did or do,” comments Ted. “They don’t want to commute far, their workplace fits what they like to do—bike, walk, eat, be close to other activities—and they are willing to trade off for these work–life fit factors over jobs that don’t have them.” Carol adds that in her last job, “Several Millennials rejected promotions and said they ‘saw what you go through and it’s not worth it to me.’”

Millennials Want Opportunity

Across the board, every Millennial I talked with articulated a strong desire not to be stuck in a job with no future. The concept of “paying your dues” came up only three times in over one hundred interviews. Opportunity for growth and access was a constant theme for Millennials in and entering the workplace.

They want access to senior management. On a scale of one to ten (ten being high), access to senior management consistently scored nine or ten with every person age twenty-two to thirty-four I interviewed from across the country. Every single one.

This is a generation who has grown up one e-mail away from any CEO or political leader in the country or even the world. The notion that someone would be unavailable to them—or that it’s okay for people in power to put a buffer between themselves and the people they lead—seems ridiculous.

Senior management are generally respected for their position, and their knowledge and experience is sought after. “I take things up the chain all the time,” says Liz, if she can see how to get things done faster. She was quick to explain that she doesn’t want to waste her time with middle managers who aren’t accessible when she needs them to be or who “don’t know how to help.”

Most importantly, the power to advance or shortcut careers is clearly understood. “I have access to everyone, and I selectively go over people’s heads because it gives me access to get knowledge, to networks, and to open doors,” says Michael, twenty-seven, from New York City. “I used to take offense when people I manage went over my head, but I get it and know that it’s not about me, it’s about them” getting the access that will give them opportunity.

They want a strong mentor. Millennials understand the value of creating a network of experienced advisors who can help open doors, navigate a job search or situation in the workplace, and provide a helping hand during a career. While parents are the primary source of mentorship for Millennials, particularly recent college graduates, other experienced advisors willing to give some time to Millennials’ worthy cause—themselves—are in high demand.

“We want to be mentored,” says Caitlin, twenty-eight from Seattle. “Older workers have a lot of transferable knowledge and advice that will leave a big mark on the younger generation.”

They want a career path. Following in Gen X’s footsteps, Millennials don’t see themselves as staying with one job or one company for their whole careers. They know that they need to take charge of their own careers, and they see a series of jobs as stepping-stones in the long yellow brick road of a career path. “They’ve always got their ears open to the next opportunity,” says Leslie, the recruiter in San Francisco. To her it seems like everyone under thirty she has placed “is coming back around to (her) within nine to twelve months to find out if there’s something better out there.”

At the same time, the Millennials I talked with who were happy in their jobs talked expressively about how much potential they saw in their positions or their companies. “I feel there’s a lot of room for growth at my company, and I’m really excited to see where it takes me,” says Sally, summing up the sentiment.

Busting Millennial Myths

Taken together, how technology impacted how Millennials were raised, the input of their parents, and the mind-set that these phenomena yield paints a different picture from what has emerged in countless articles, books, conversations, forums, and blog comment sections. While it’s easy to understand where the prevailing myths about Millennials and their work habits come from, we need to break down the myths based on their upbringing, not ours, if we’re going to successfully figure out how to productively collaborate and work with them. Knowing what we know now, where does that leave us with the prevailing myths?

Myth #1: Millennials are entitled. Busted: Millennials are conditioned. They don’t want anything we don’t all desire! They are us in younger bodies and with different parents. Millennials have been taught to expect certain conditions immediately that older workers had to wait for. To compound the problem, their entry into the job market came at a terrible time, economically.

Myth #2: Millennials expect rewards and promotions for showing up. Plausible: They’ve gotten rewards for simple participation all along the way, so many don’t know what mastery looks like.

Myth #3: Millennials don’t work hard. Busted: Millennials work differently, and sometimes don’t know what good work is, which is not the same thing as “don’t work hard.”

Myth #4: Millennials can’t get anything done. Busted: Millennials need context to get started and feedback to cross the finish line, but their output can be phenomenal.

Myth #5: Millennials are casual and disrespectful. Half busted/half plausible: As a culture, we are much less formal in our dress than we were twenty, thirty, or forty years ago—John F. Kennedy started the whole thing when he refused to wear hats in 1960. Millennials have not been taught what is appropriate in the workplace, and don’t know how other, older colleagues perceive them.

Myth #6: Millennials want freedom, flexibility, and work–life balance. Split decision: Freedom? Some want the freedom to be anywhere, while others value being in the office. Work–life balance? Confirmed: they have seen the compromised work–life mix that many Baby Boomers and Gen Xers have, and don’t want it for themselves.

Now What?

So what’s a tired forty-six-year-old who sees this and wants to call in sick tomorrow supposed to do? “Seriously, I worked this hard for this long, and this is what I have to deal with? I’ve earned the right to go into my office and shut the door,” says Kate, forty-six, a general manager of a Boston-based marketing firm. The problem, according to Kate, is that it takes “a whole lot of energy to harness those demands in a constructive way. I’ve put my energy into getting here, and the game has changed. I’m all about servant leadership, but this is ridiculous. It never stops.”

Here’s the deal. We all need to do a few things to improve the workplace dynamic that seems to pit generation against generation. First: Boomers and Xers need to stop assuming every young person is the same. Millennials need to stop assuming everyone older than they are is out of touch and unproductive. Just as I don’t want to be lumped in with the bad actors of my generation, Millennials don’t want to be judged by a misunderstood perception about their generation.

Second: We need to get people over the first four years of their careers (whenever it really starts). The early twenties are a time of huge transformation, excitement, and uncertainty. It’s always been hard to go from school, where the kid with straight As and the kid with the C average both advanced to the next grade despite their disparate achievements, to the workplace, where achievement rather than time is valued for advancement. This is not new. I am famous for saying in a 1991 interview with a potential employee, “I’m not going to be your *&^%ing babysitter.” Yeah, I was a gem.

Third: Just because we didn’t get what our younger colleagues are asking for (okay, demanding) doesn’t mean we shouldn’t give it to them. Because we’ll be giving it to ourselves too! Who doesn’t want to understand how they fit into the bigger picture? Who doesn’t want to be acknowledged for their contribution? Who doesn’t want to matter? The challenge is not to stop these things from happening, the challenge is to move from assuming that everyone knows what to do to articulating expectations clearly and then maintaining them.

Fourth: Boomers and Xers can learn from younger colleagues. We Boomers and Xers need to meet our younger colleagues where they are and move them forward. At the same time, we all need to be open to learning from one another.

This doesn’t mean that managers have to do all the work or not hold Millennials accountable. But managers do need to explain tasks and standards of work more concretely and consistently.

In the end, we will all be better off if we move some of our management styles around a bit and find ways of working together that benefit everyone.