RULE 8

Avoid Seduction

The trouble with taking charge of your own finances is the risk of falling for some kind of scam. Learning how to beat the vast majority of professional investors is easy: invest in index funds. But some people make the mistake of branching off to experiment with alternative investments.

Achieving success with a new financial strategy can be one of the worst things to happen. If something works out over a one-, three- or five-year period, there's going to be a temptation to do it again, to take another risk. But it's important to control the seductive temptation of seemingly easy money. There's a world of hurt out there and rascals keen to separate you from your hard-earned savings. In this chapter, I'll examine some of the seductive strategies used by marketers out for a quick buck. With luck, you'll avoid them.

Confession Time

Perhaps I'm justifying this to feel better about myself, but this is what I believe: Any investor who doesn't have a story relating to a really dumb investment decision is probably a liar. So I'm going to roll up my sleeves and tell you about the dumbest investment decision I ever made. It might prevent you from making a similar, silly mistake.

The dumbest investment I ever made

In 1998, a friend of mine asked me if I would be interested in investing in a company called Insta-Cash Loans. “They pay 54 percent annually in interest,” he whispered. “And I know a few guys who are already invested and collecting interest payments.”

For any half-witted investor, the high interest rate should have raised red flags. Around that time, I was reading about the danger of high-paying corporate bonds issued by companies such as WorldCom, which was yielding 8.3 percent. The gist of the warning was this: If a company is paying 8.3 percent interest on a bond in a climate where four percent is the norm, then there has to be a troublesome fire burning in the basement. Not long after WorldCom issued its bonds, the company declared bankruptcy. It was borrowing money from banks to pay its bond interest.1

The 54 percent annual return that my friend's investment prospect paid was a Mt. Everest of interest compared with Worldcom's speed bump. It rightfully scared me to think of how crazy the investment venture must be, telling my friend as much:

“Look,” I said, “Insta-Cash Loans isn't really paying you 54 percent interest. If you give the company $10,000, and the company pays out $5,400 at the end of the year in ‘interest,’ you've only received slightly more than half of your investment back. If that guy disappears into the Malaysian foothills with that $10,000, you get the shaft. You'd lose $4,600.”

It seemed totally crazy. But what's even crazier is that I eventually changed my mind.

After the first year, my friend told me that he had received his 54 percent interest payment. “No you didn't,” I insisted. “Your original money could still vaporize.”

The following year, he received 54 percent in interest again, paid out regularly with 4.5 percent monthly deposits into his bank account.

Although I still thought it was a scam, my conviction was losing steam. It appeared that now he was ahead of the game, receiving more in interest than he had given the company in the first place.

He increased his investment to $80,000 in Insta-Cash Loans, which paid him $43,200 annually in “interest.”

As a retiree, he was able to travel all over the world on these interest payments. He went to Argentina, Thailand, Laos, and Hawaii—all on the back of this fabulous investment.

After about five years, he convinced me to meet the head of this company, Daryl Klein (and yes, that's his real name). How was Insta-Cash Loans able to pay out 54 percent in interest every year to each of its investors? I wanted to know how the business worked.

I drove to the company's headquarters in Nanaimo, British Columbia, with a friend who was also intrigued.

Pulling alongside the curb in front of Daryl's office, I was skeptical. Daryl was standing on the sidewalk in a creased shirt with his sleeves rolled up, a cigarette in hand.

We settled into Daryl's office and he explained the business. Initially, he had intended to open a pawn brokerage but changed his mind when he caught on to the far-more lucrative business of loaning money and taking cars as collateral. As a result, Insta-Cash Loans was created.

In a narrative recreation, this is what he said:

I loan small amounts of short-term money to people who wouldn't ordinarily be able to get loans. For example, if a real estate agent sells a house and knows he has a big commission coming and he wants to buy a new stereo right away, he can come to me if his credit cards are maxed out and if he doesn't have the cash for the stereo.

“How does that work?” I wanted to know.

Well, if he owns a car outright, and he turns the ownership over to me, I'll loan him the money. The car is just collateral. He can keep driving it, but I own it. I charge him a high-interest rate, plus a pawn fee, and if he defaults on the loan, I can legally take the car. When he repays the loan, I give the car's ownership back.

“What if they just take off with the car?” I asked.

I have some great retired ladies working for me who are fabulous at tracking down these cars. One guy drove straight across the country when he defaulted on the loan. One of these ladies found out that he was in Ontario (about a six-hour flight from Daryl's office in British Columbia) and before the guy even knew it, we had that car on the next train for British Columbia. In the end, we handed him the bill for the loan interest, plus the freight cost for his car.

It sounded like a pretty efficient operation to me. But I wanted to know if the guy had a heart. “Hey Daryl,” I asked, “have you ever forgiven anyone who didn't pay up?”

Leaning back in his chair with a self-satisfied smile, Daryl told the story of a woman who borrowed money from him, using the family motor home as collateral. She defaulted on the loan, but she didn't think it was fair that Daryl should be able to keep the motor home. Her husband had not known about the loan. He came into Daryl's office with a lawyer, but the contract was legally airtight; there was nothing the lawyer could do about it.

But, as Daryl explained, he took pity on the woman and gave the motor-home ownership back to the couple.

It sounded like an amazing operation.

However, nobody can guarantee you 54 percent on your money—ever. Bernie Madoff, the currently incarcerated Ponzischeming money manager in the U.S. promised a minimum return of 10 percent annually and he sucked scores of intelligent people into his self-servicing vacuum cleaner—absconding with $65 billion in the process.2 He claimed to be making money for his clients by investing their cash mostly in the stock market, but he just paid them “interest” with new investors' deposits. The account balances that his clients saw weren't real. When an investor wanted to withdraw money, Madoff took the proceeds from fresh money that was deposited by other investors.

When the floor finally fell out from underneath Madoff during the 2008 financial crisis, investors lost everything. His victims included actors Kevin Bacon, his wife Kyra Sedgwick, and director Steven Spielberg, among the many others who lost millions with Madoff.3

Yet the percentages paid by Madoff were chicken feed compared with the 54 percent caviar reaped by Daryl Klein's investors.

Despite the solid-sounding story Daryl told me back in 2001, I still wouldn't invest money with the guy.

But my friend kept receiving his interest payments, which now exceeded $100,000.

By 2003, I had seen enough. My friend had been making money off this guy for years and my “spidey senses” were tickled more by greed than danger. I met with Daryl again, and I invested $7,000. Then I convinced an investment club that I was in to dip a toe in the water. So we did, investing $5,000. The monthly 4.5 percent interest checks were making us feel pretty smart. After a year, the investment club added another $20,000.

Other friends were also tempted by the easy money. One friend took out a loan for $50,000 and plunked it down on Insta-Cash Loans, and he began receiving $2,250 a month in interest from the company.

Another friend deposited more than $100,000 into the business; he was paid $54,000 in yearly interest. But Alice's Wonderland was more real than our fool's paradise.

Like Bernie Madoff (who was caught after Daryl) the party eventually ended in 2006 and the carnage was everywhere. We never found out whether Daryl intended for his business to be a Ponzi scheme from the beginning (he was clearly paying interest to investors from the deposits of other investors) or whether his business slowly unraveled after a well-intentioned but ineffective business plan went awry.

Klein was eventually convicted of breaching the provincial securities act, preventing him from engaging in investor-relations activities until 2026.4

The fact that he was slapped on the wrist, however, was small consolation for his investors. A few had even remortgaged their homes to get in on the action.

Our investment club, after collecting interest for just a few months, lost the balance of our $25,000 investment. My $7,000 personal investment also evaporated. Many investors in the company lost everything. My friend who borrowed $50,000 to invest, collected interest for 10 months (which he had to pay taxes on) before seeing his investment balance disappear when Insta-Cash Loans went bankrupt in 2006.

It's an important lesson for investors to learn. At some point in your life, someone is going to make you a lucrative promise. Give it a miss. In all likelihood, it's going to cause nothing but headaches—not to mention a potential black hole in your bank account.

Investment Newsletters and Their Track Records

In 1999, the same investment club mentioned earlier was trying to get an edge on its stock picking. We purchased an investment newsletter subscription called the Gilder Technology Report, <www.gildertech.com/> published by a guy named George Gilder. Unbelievably, he is still in business. A quick online search today reveals a website that exhorts his stock picks, claiming his portfolio returned 155 percent during the past three years, and that if you buy now, you'll pay just $199 for the 12-month online subscription to his newsletter. If you're falling for that promotional garbage, I have a story for you.5

Back in 1999, we were convinced that George Guilder held the keys to the kingdom of wealth. Unfortunately for us, he was the king of pain. Today, if George Gilder reported his 11-year track record online (instead of trying to tempt investors with an unaudited three-year historical return) he would have a stampede of exiters. His stock picks have been abysmal for his followers.

We bought the George Gilder technology report in 1999 and we put real money down on his suggestions. I'm just hoping my investment club buddies don't read this book and learn that George Gilder is still hawking his promises of wealth. They'd probably want to send him down a river in a barrel.

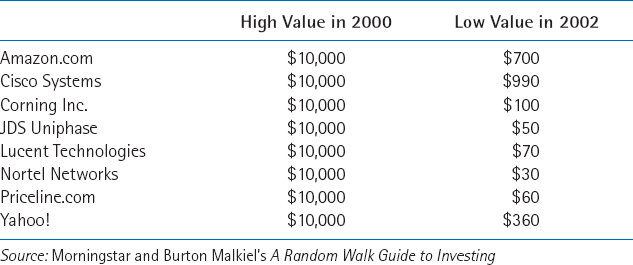

Back in Chapter 4, I showed you a chart of technology companies and how far their share prices fell from 2000 to 2002.

In 2000, whose investment report recommended purchasing Nortel Networks <www.nortel.com>, Lucent Technologies <www.alcatel-lucent.com>, JDS Uniphase <www.jdsu.com> and Cisco Systems <www.cisco.com/>? You guessed it: George Gilder's.

Table 8.1 puts the reality in perspective. If you had a total of $40,000 invested in the above four “Gilder-touted” businesses in 2000, it would have dropped to $1,140 by 2002.

And how much would your investment have to gain to get back to $40,000?

Table 8.1 Prices of Technology Stocks Plummet (2000–2002)

In percentage terms, it would need to grow 3,400 percent.

Wow—wouldn't that be a headline for the Gilder Technology Report today?

“Since 2002, our stock picks have made 3,400 percent”

If that really happened, George Gilder would be advertising those numbers on his site rather than showcasing a measly return of 155 percent over the past three years.

George Gilder's stock picks have tossed investors into the Grand Canyon and he's bragging that his investors have scaled back about 50 feet. He could tell the truth about his real stock-picking prowess, but then he couldn't fool newsletter subscribers looking for keys to easy wealth. There are no keys to easy wealth—so don't be fooled by advertised claims.

Just for fun, let's assume that Gilder's original stock picks from 2000 did make 3,400 percent from 2002 to 2011. That might impress a lot of people. But it wouldn't impress me. After the losses that Gilder's followers experienced from 2000 to 2002, a gain of 3,400 percent would have his long-term subscribers barely breaking even on their original investment after a decade—and that's if you didn't include the ravages of inflation.

If there are any long-term subscribers, they're nowhere near their break-even point. Can you hear his followers scrambling on the lowest slopes of the Grand Canyon? I wonder if they're thirsty.

Where there is a buck to be taken

We already know that the odds of beating a diversified portfolio of index funds, after taxes and fees, are slim. But what about investment newsletters? You can find more beautifully marketed newsletter promises than you can find people in a Tokyo subway. They selectively boast returns (like Gilder does), creating mouthwatering temptations for many inexperienced investors:

With our special strategy, we've made 300 percent over the past 12 months in the stock market, and now, for just $9.99 a month, we'll share this new wealth-building formula with you!

Think about it. If somebody really could compound money 10 times faster than Warren Buffett, wouldn't she be at the top of the Forbes 400 list? And if she did have the stock market in the palm of her hand, why would she want to spend so much time banging away at her computer keyboard so she could sell $9.99 subscriptions to you?

Let's look at the real numbers, shall we?

Most newsletters are like dragonflies. They look pretty, they buzz about, but sadly, they don't live very long. In a 12-year study from June 1980 to December 1992, professors John Graham at the University of Utah and Campbell Harvey at Duke University tracked more than 15,000 stock market newsletters. In their findings, 94 percent went out of business sometime between 1980 and 1992.6

If you have the Midas touch as a stock picker who spreads pearls of financial wisdom in a newsletter, you're probably not going to go out of business. If you can deliver on the promise of high annual returns, you'll build a newsletter empire. If no one, however, wants to read what you have to say (because your results are terrible) the newsletter follows the sad demise of the woolly mammoth.

There are several organizations that track the results of financial newsletter stock picks and The Hulbert Financial Digest is one of them. In its January 2001 edition, the U.S. -based publication revealed it had followed 160 newsletters that it had considered solid. But of the 160 newsletters, only 10 of them had beaten the stock market indexes with their recommendations over the past decade. Based on that statistic, the odds of beating the stock market indexes by following an investment newsletter are less than seven percent.7

Put another way, how would this advertisement grab you?

You could invest with a total stock market index fund—or you could follow our newsletter picks. Our odds of failure (compared with the index) are 93 percent. Sign up now!

If investors knew the truth, financial newsletters probably wouldn't exist.

High-Yielding Bonds Called “Junk”

At some point, you might fight the temptation to buy a corporate bond paying a high interest percentage. It's probably best to avoid that kind of investment. If a company is financially unhealthy, it's going to have a tough time borrowing money from banks, so it “advertises” a high interest rate to draw riskier investors. But here's the rub: If the business gets into financial trouble, it won't be able to pay that interest. What's worse, you could even lose your initial investment.

Bonds paying high interest rates (because they have shaky financial backing) are called junk bonds.

I've found that being responsibly conservative is better than stretching over a ravine to pluck a pretty flower.

Fast-Growing Markets Can Make Bad Investments

A friend of mine once told me: “My adviser suggested that, because I'm young, I could afford to have all of my money invested in emerging market funds.” His financial planner dreamed of the day when billions of previously poor people in China or India would worship their 500-inch, flat-screen televisions, watching The Biggest Loser while stuffing their faces with burgers, fries, and gallons of Coke. Eyes sparkle at the prospective burgeoning profits made by investing in fattening economic waistlines. But there are a few things to consider.

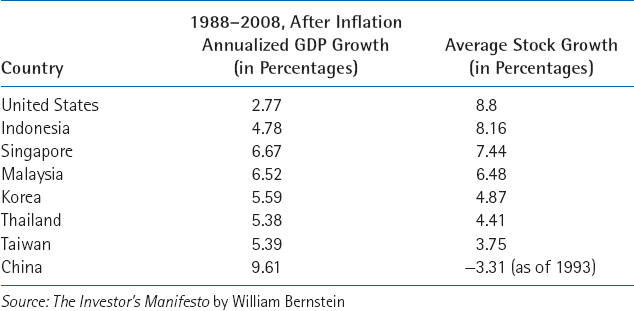

Historically, the stock market investment returns of fast-growing economies don't always beat the stock market growth of slowgrowing economies. William Bernstein, using data from Morgan Stanley's capital index and the International Monetary Fund, reported in his book, The Investor's Manifesto, that fast-growing countries based on gross domestic product (GDP) growth paradoxically have produced lower historical returns than the stock markets in slower growing economies from 1988 to 2008.

Table 8.2 shows that when we take the fastest growing economy (China's economy) and compare it with the slowest growing economy (the U.S.) we see that investors in U.S. stock indexes would have made plenty of money from 1993 to 2008. But if investors could have held a Chinese stock market index over the same 15-year period, they would not have made any profits despite China's GDP growth of 9.61 percent a year over that period.

Table 8.2 Growing Economies Don't Always Produce Great Stock Market Returns

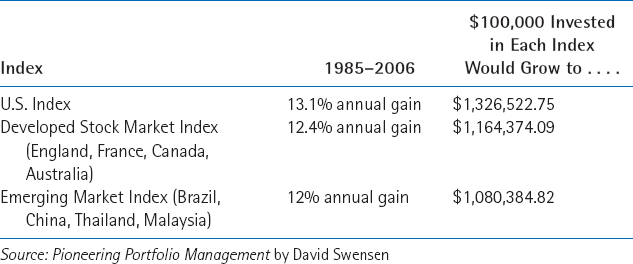

Similarly, as revealed in Table 8.3, Yale University's celebrated institutional investor, David Swensen, warns endowment fund managers not to fall into the GDP growth trap either. In his book written for institutional investors, Pioneering Portfolio Management, he suggests from 1985 (the earliest date from which the World Bank's International Finance Corporation began measuring emerging market stock returns) to 2006, the developed countries' stock markets earned higher stock market returns for investors than emerging market stocks did.

Table 8.3 Emerging Market Investors Don't Always Make More Money

Emerging markets might be exciting—because they do rise like rockets, crash like meteorites, before rising like rockets again. But if you don't need that kind of excitement in your portfolio, you might be better off going with a total international stock market index fund instead of adding a large emerging-market component.

Whether the emerging markets prove to be future winners is anyone's guess. They might. But it's wise to temper expectations with historical realities, just in case.

Gold Isn't an Investment

Our education systems have done such a lousy job teaching us about money that you can conduct a little experiment out on the streets that I guarantee will deliver shocking results.

Walk up to an educated person and ask them to imagine that one of their forefathers bought $1 worth of gold in 1801. Then ask what they think it would be worth in 2011.

Their eyes might widen at the thought of the great things they could buy today if they sold that gold. They might imagine buying a yacht or Gulfstream jet, or their own island in the South China Sea.

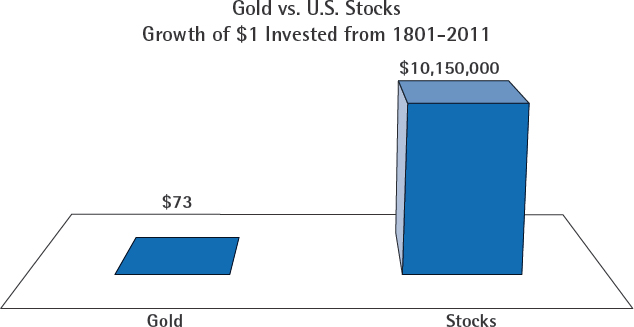

Then break their bubble with the revelation in Figure 8.1. Selling that gold would give them enough money to fill the gas tank of a minivan.

One dollar invested in gold in 1801 would only be worth about $73 by 2011.

Figure 8.1 Gold vs. U.S. Stocks (1801–2011)

How about $1 invested in the U.S. stock market?

Now you can start thinking about your yacht.

One dollar invested in the U.S. stock market in 1801 would be worth $10.15 million by 2011.8

Gold is for hoarders expecting to trade glittering bars for stale bread after a financial Armageddon. Or it's for people trying to “time” gold's movements by purchasing it on an upward bounce, with the hopes of selling before it drops. That's not investing. It's speculating. Gold has jumped up and down like an excited kid on a pogo stick for more than 200 years, but after inflation, it hasn't gained any long-term elevation.

I prefer the Tropical Beach approach:

- Buy assets that have proven to run circles around gold (rebalanced stock and bond indexes would do).

- Lay in a hammock on a tropical beach.

- Soak in the sun and patiently enjoy the long-term profits.

What You Need to Know about Investment Magazines

If investment magazines were altruistically created to help you achieve wealth, you'd have the same cover story during every issue: Buy Index Funds Today.

But nobody would buy the magazines. It wouldn't be newsworthy. Plus, magazines don't make much money from subscriptions. They make the majority of their money from ads. Pick up a finance magazine and thumb through it to see who's advertising. The financial service industry, selling mutual funds and brokerage services, is the biggest source of advertisement revenue. Few editors would go out on a tree branch to broadcast the futility of picking mutual funds that will beat the market indexes. Advertisers pay the bills for financial magazines. That's why you see magazine covers suggesting: “The Hot Mutual Funds to Buy for 2011.”

When I wrote an article in 2005 for MoneySense magazine, titled “How I Got Rich on a Middle Class Salary,” I mentioned the millionaire mechanic, Russ Perry (who I introduced to you in Chapter 1). I quoted Russ's opinion on buying new cars—that it wasn't a good idea, and that people should buy used cars instead.

Based on a conversation I had with Ian McGugan, the magazine's editor, I learned that one of America's largest automobile manufacturers called McGugan on the phone and threatened to pull its advertisements if it saw anything like that in MoneySense again. There are bigger forces at play than those wanting to educate you in the financial magazine industry.

I have an April 2009 issue of SmartMoney magazine on my desk as I'm writing this. It would have been written a month earlier when the stock market was reeling from the financial crisis. Instead of shouting out: “Buy stocks now at a great discount!” the magazine was giving people what they wanted: A front cover showing a stack of $100 bills secured by a chain and padlock with the screaming headlines: “Protect Your Money!,” “Five Strong Bond Funds,” “Where to Put Your Cash,” and “How to Buy Gold Now!”. Think about it. They have to. If the general public is scared stiff of the stock market's drop, they'll want high doses of chicken soup for their knee-jerking souls. They'll want to know how to escape from the stock market, not embrace it. Giving the public what it pines for when they're scared might sell magazines. But you can't make money being fearful when others are fearful.

I don't mean to pick on SmartMoney magazine. I can only imagine the dilemma it faced when putting that issue together. Its writers are smart people. They know—especially for long-term investors—that buying into the stock market when it's on sale is a powerful wealth-building strategy. But a falling stock market, for most people, is scarier than a rectal examination. Touting bond funds and gold was an easier sell for the magazine.

Let's have a look at the kind of money you would have made if you followed that April 2009 edition of SmartMoney.

It suggested placing your investment in the following bond funds: the Osterweis Strategic Income Fund <www.osterweis.com/default.asp?P>, the T. Rowe Price Tax-Free Income Fund <www.3troweprice.com/fb2/fbkweb/snapshot.do?ticker=PRTAX>, the Janus HighYield Fund<https://ww3.janus.com/Janus/Retail/FundDetail?fundID=14>, the Templeton Global Bond Fund <www.franklintempleton.com/retail/app/product/views/fund_page.jsf?fundNumber=406>, and the Dodge & Cox Income Fund <www.dodgeandcox.com/incomefund.asp>.

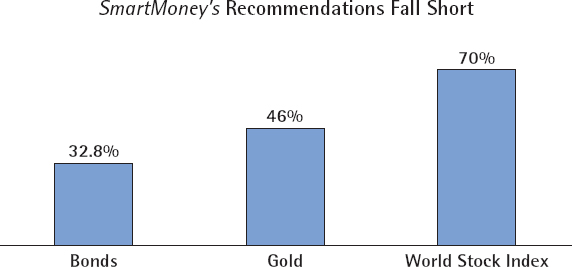

Table 8.4 shows that with reinvesting the interest, SmartMoney's recommended bond funds would have returned an average of 32.8 percent from April 2009 to January 2011.

How about gold, which was also recommended by that edition of SmartMoney? Its spectacular run would have seen it gain 46 percent during the same period, as gold was hitting an all-time high.

Table 8.4 Percentages of Growth (April 2009-January 2011)

Source: Morningstar9

So far, it looks like the magazine was right on the money, until you look at what they didn't headline. Stock prices were cheaper, relative to business earnings, than they had been in decades. The magazine headlines should have read: “Buy Stocks Now!”.

Because they didn't, as demonstrated by Figure 8.2, SmartMoney readers missed out on some huge gains, as stocks easily beat bonds and gold from April 2009 to January 2011.

The U.S. stock market (as measured by Vanguard's U.S. stock market index) increased 69 percent, Vanguard's international stock market index rose by 70 percent, and Vanguard's total world index rose by 70 percent during the same period.

The comparative results punctuate how tough predictions can be, while emphasizing that magazines cater for their advertisers and their reader's emotions to sell magazines.

Figure 8.2 Bond Funds and Gold vs. Stocks (April 2009-January 2011): Source: Morningstar10

Hedge Funds—The Rich Stealing from the Rich

Some wealthy people turn their noses up at index funds, figuring that if they pay more money for professional financial management, they'll reap higher rewards in the end. Take hedge funds for example. As the investment vehicle for many wealthy, accredited investors (those deemed rich enough to afford taking large financial gambles), hedge funds capture headlines and tickle greed buttons around the world, despite their hefty fees.

But by now, it probably comes as no surprise that, statistically, investing with index funds is a better option. Hedge funds can be risky, and the downside of owning them outweighs the upside.

First the upside

With no regulations to speak of (other than keeping middle-class wage earnings on the sidelines) hedge funds can bet against currencies or bet against the stock market. If the market falls, a hedge fund could potentially make plenty of money if the fund manager “shorts” the market, by placing bets that the markets will fall and then collecting on these bets if the markets crash. With the gift of having accredited (supposedly sophisticated) investors only, hedge fund managers can choose to invest heavily in a few individual stocks—or any other investment product, for that matter—while a regular mutual fund has regulatory guidelines with a maximum number of eggs they're allowed to put into any one basket. If a hedge fund manager's big bets pay off, investors reap the rewards.

Now for the downside

The typical hedge fund charges two percent of the investors' assets annually as an expense ratio, which is one-third more expensive than the expense ratio of the average U.S. mutual fund. Then the hedge funds' management takes 20 percent of their investors' profits as an additional fee to generate profits for fund managers or for the business offering the fund. It's a license to print money off the backs of those hoping for high rewards.

Hedge funds voluntarily report their results, which is the first phase of mist over the industry. The Economist reports the average (unaudited) returns of hedge funds on the back of each issue, comparing the results to various world indexes. I have been scanning the results for a decade or more, and generally the hedge funds compare favorably—from what I have seen—by a consistent percentage or two above the indexes.

But hedge fund data collectors don't crunch the numbers for the hedge funds that go out of business. They only report the results of those that remain. So what's the attrition rate for these investment products?

When Princeton University's Burton Malkiel and Yale School of Management's Robert Ibbotson conducted an eight-year study of hedge funds from 1996 to 2004, they reported that fewer than 25 percent of funds lasted the full eight years.11Would you want to pick from a group of funds with a 75 percent mortality rate? I wouldn't.

When looking at reported average hedge fund returns, you only see the results of the surviving funds—the constantly dying funds aren't factored into the averaging. It's a bit like a coach entering 20 high school kids in a district championship cross-country race. Seventeen drop out before they finish, but your three remaining runners take the top three spots and you report in the school newspaper that your average runner finished second. Bizarre? Of course, but in the fantasy world of hedge fund data crunchers, it's still “accurate.”

As a result of such twilight-zone reporting, Malkiel and Ibbotson found during their study that the average returns reported in databases, were overstated by 7.3 percent annually.

These results include survivorship bias (not counting those funds that don't finish the race) and something called “back-fill bias.” Imagine 1,000 little hedge funds that are just starting out. As soon as they “open shop” they start selling to accredited investors. But they aren't big enough or successful enough to add their performance figures to the hedge fund data crunchers—yet.

After 10 years, assume that 75 percent of them go out of business, which is in line with Malkiel and Ibbotson's findings. For them, the dream is gone. And it's really gone for the people who invested with them.

Of those (the 250) that remain, half have results of which they're proud, allowing them to grow and to boast of their successful track records. So out of 1,000 new hedge funds, 250 remain after 10 years, and 125 of them grow large enough (based on marketing and success) to report their 10-year historical gains to the data crunchers compiling hedge fund returns. The substandard or bankrupt funds don't get number crunched. Ignoring the weaker funds and highlighting only the strongest ones is called a “backfill bias.”

Doing so ignores the mortality of the dead funds and it ignores the funds that weren't successfully able to grow large enough for database recognition. Malkiel and Ibbotson's study found that this bizarre selectiveness spuriously inflated hedge fund returns by 7.3 percent annually over the period of their study.12

To make matters even worse, hedge funds are remarkably inefficient after taxes, based on the frequency of their trading. Plus, you never know ahead of time which funds will survive and which funds will die a painful (and costly) death.

Hedge funds are like hedgehogs. Nice to look at from afar, but you really don't want to get too close to their spines. You're far better off in a total stock market index fund.

When investing, seductive promises and get-rich-quicker schemes can be tempting. But they remind me of why I don't take experimental shortcuts when hiking. It's too easy to lose your way. I wonder if the famous French writer, Voltaire, would agree. In a translation from his 1764 Dictionnaire Philosophique he wrote: “The best is the enemy of good.”13 Investors who aren't satisfied with a good plan—like indexing—may strive for something they hope will be “best.” But that path's wake is filled with more tragedies than successes.

Notes

1 Benjamin Graham (revised by Jason Zweig) The Intelligent Investor (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2003), 146.

2 Erin Arvedlun, Madoff, The Man Who Stole $65 Billion (London: Penguin, 2009), 6.

3 Ibid., 85.

4 “Daryl Joseph Klein and Kleincorp Management Doing Business as Insta-Cash Loans,” The Manitoba Securities Commission, order no.5753: August 13, 2008, accessed April 15, 2011, http://www.msc.gov.mb.ca/legal_docs/orders/klein.html.

5 Gilder Technology Report, accessed October 15, 2010, http://www.gildertech.com/.

6 Mel Lindauer, Michael LeBoeuf, and Taylor Larimore, The Bogleheads Guide to Investing (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), 158.

7 Ibid., 159.

8 Calculated from 1801–2001 returns of U.S. stocks and gold from Jeremy Siegel, Stocks for the Long Run, (New York: McGraw Hill, 2002), then extrapolated further using gold's 2001 price, accessed April 15, 2011, http://www.usagold.com/analysis/2009-gold-prices.html, and compared with its 2011 price, yahoofinance.com.

10 Ibid.

11 Swensen, Pioneering Portfolio Management, An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment, 195.

12 Ibid.

13 Voltaire quote: Famous Quotes, accessed April 15, 2011, http://www.famous-quotes.net/Quote.aspx?The_perfect_is_the_enemy_of_the_good.