RULE 6

Sample a “Round-the-World” Ticket to Indexing

Contrary to what some investment books have inadvertently led you to conclude, index funds have boarded ships and airplanes to find happy homes outside of the United States. In this section, I'll give you examples of how to build an indexed account whether you live in the U.S., Canada, Singapore, or Australia. Feel free to check out the section relating to your geographic area, or read with interest how our international brothers and sisters can create indexed accounts. Even if you live in a country not mentioned here, as long as you have the ability to open a brokerage account in your home country, you can build a portfolio of indexes.

The people I'm profiling below are real. These are their real names—and their real stories.

Indexing in the United States—An American Father of Triplets

When Kris Olson's wife, Erica, had triplets in 2006, she singlehandedly gave birth to a quarter of a soccer team. Suddenly, there were three more mouths to feed, a minivan to buy, and three college educations to save for.

I'm not suggesting that anyone would hold a charitable benefit with accompanying violin music for a well-paid specialist in pediatrics and internal medicine. But if you're American, and suddenly more aware of your own financial obligations, Kris' story of opening an indexed investing account could provide some direction.

The 40-year-old doctor realized that investing money was similar, in many ways, to the global health work he does in the povertystricken, tsunami-affected regions of Sumatra, Indonesia, where he occasionally flies to train midwives. This latest passion comes on the tail of his volunteer work along the Thai-Burmese border, as well as in Darfur, Cambodia, Kenya, and Ethiopia.

Realizing that donations to developing countries are best done in person, he and his wife Erica (a registered nurse) often brought their own medical supplies to the countries they visited. Simply sending supplies was an invitation for third-world middlemen to plunder the goods before they arrived.

In 2004, Kris recognized that something similar was happening to his investments at home, which had been laboring in actively managed mutual funds for years.

“My financial adviser was a really nice guy, but I realize that he skimmed money off me like guys at a third-world country border. I was flushing money down the toilet in tiny sums that were adding up,” he said.

On a trip to Indonesia, Kris made a stopover in Singapore, where he purchased cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training material to take to midwives in Aceh. I met him for lunch at a Japanese restaurant, and over sushi, he asked me what indexes he should buy for his investment account.

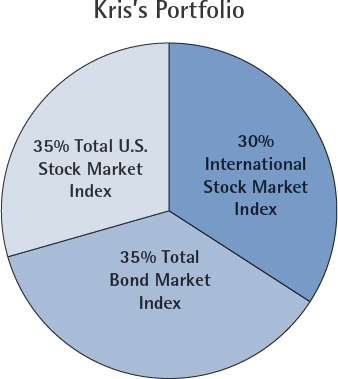

The largest index provider in the U.S. is Vanguard, a nonprofit investment company based in Pennsylvania. If you go to their website, the array of indexes can be confusing at first. But I suggested that Kris—who was 35 years old at the time—should keep things simple: buy the broadest stock index he could for his U.S. exposure, the broadest international index he could for his “world” exposure, and a total bond market index fund that approximated his age. Here's the allocation I recommended:

- 35% Vanguard U.S. Bond Index (Symbol VBMFX)

- 35% Vanguard Total U.S. Stock Market Index (Symbol VTSMX)

- 30% Vanguard Total International Stock Market Index (Symbol VGTSX)

I gave my advice on this basis: Vanguard doesn't charge commissions to buy or sell; he would be diversified across the entire U.S. stock market and the international stock markets; and he would have a bond allocation that would allow him to rebalance his account annually.

“Kris,” I said, “don't listen to Wall Street, don't read financial newspapers, and don't watch stock market-based news. If you rebalance a portfolio like this just once a year, you'll beat 90 percent of investment professionals over time.”

When Kris got back home to the U.S., he put his old mutual fund investment statements on the dining room table, logged on to the Vanguard site, and telephoned the company from the website's contact information.

A Vanguard employee walked Kris through the account opening process as they negotiated the website together. She simply asked for his existing mutual fund account numbers—for both his IRA account (a tax-sheltered individual retirement account) and for his non-IRA mutual funds.

Over the telephone, the Vanguard representative then transferred his assets from his previous fund company to Vanguard where he diversified his money into the three index funds. Then, after taking his regular bank account information, she set up automatic deposits into Kris's index funds according to the allocation he wanted.

At the end of each calendar year, Kris took a look at his investments. “It didn't take much,” he said. “I just rebalanced the portfolio back to the original allocation at the end of each year, (as seen in Figure 6.1) selling off a bit of the ‘winners’ to bolster the ‘losers.’ It was the only time I ever looked at my investment statements—just when it was time to consider rebalancing.” I was able to confirm Kris's investment returns (in U.S. dollars) using the fund-tracking function at Morningstar.com.

January 2007

Kris noticed that the portfolio he established one year earlier had gained 15.4 percent during the course of the year, with most of the gains coming from his international and U.S. stock market indexes. He called Vanguard on the phone, logged on to his account online, and the Vanguard representative guided him through the process of selling off some of his stock indexes to buy his bond index, bringing him back to his desired allocation. Kris was ready to tune Wall Street out for another year with his portfolio aligned the way it was when he started.

Figure 6.1 Kris Olson's Account Allocation

January 2008

Worldwide, stock markets continued to rise from 2007 to 2008. At this point, Kris's profits had really increased, gaining 25.86 percent from the initial 2006 value and nine percent for the 2007 calendar year. Fighting the urge to buy more of what was propelling his portfolio (his stock indexes), Kris sold off portions of his international and U.S. stock indexes to buy more of his bond index with the proceeds. It didn't require any judgment on his part—he just adjusted his account back to its original allocation.

January 2009

When Kris looked at his statements at the beginning of 2009, he noticed his total portfolio had dropped in value as the biggest stock market decline since 1929–1933 was starting to take its toll. It fell 24.5 percent but Kris just rebalanced his portfolio again, selling off some of his bond index to buy falling U.S. and international stock indexes, bringing it back to the original allocation.

January 2010

Kris knew the stock markets took a real beating during the previous year—everyone was talking about it. But because he sold off some bonds the previous year to buy stocks, he benefited from the low stock market levels. By January 2010, his account had increased 23 percent for the year thanks to the rebounding stock markets. Once again, Kris took 10 minutes in January to rebalance his account, selling some stock indexes to buy more of his bond index. When Kris was finished, he was back to his original allocation.

January 2011

By January 2011, Kris' account had gained another 11.6 percent over the previous 12 months. From January 1, 2006, until January 1, 2011, his account's profits had increased by 30.7 percent, despite going through the worst stock market decline (2008–2009) in many years.1 Rebalancing once again, he sold off some of his stock indexes to buy some more of his bond index. Considering that Kris is now 40 years old, he should be increasing his bond allocation slowly to match his age.

A medical doctor knocks out the investment professionals

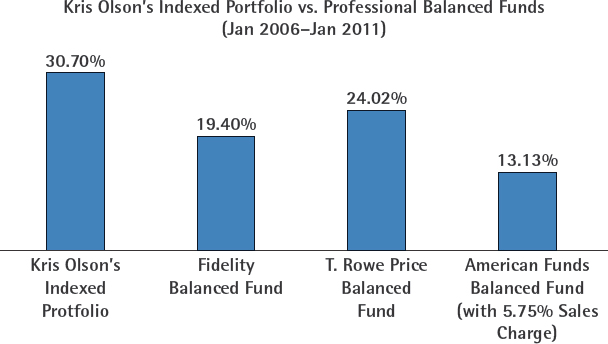

It's fine for Kris's portfolio to have gained 30.7 percent from January 2006 to January 2011, but how would it have done if it was professionally managed by a fund manager with his or her pulse on the markets?

You'd assume that a doctor spending just 10 minutes a year on his finances would get scalped if he ever challenged the investment professionals. But here's the rub. If a mutual fund could be managed for free—with no salaries paid to any affiliated employees—then Kris's odds of beating the professionals with a fully indexed account would be slightly less than 50–50. (After all, he's paying rock-bottom fees to own the world's stock and bond markets, and only about 50 percent of actively managed stock market money will beat the market [before fees].) However, by factoring in the real fees of active management along with taxes, the good doctor operates in a climate where the odds are significantly in his favor—if he indexes his money.

Because Kris's account is balanced between stocks and bonds, we can check his performance, in Figure 6.2 compared with three of the best known balanced mutual funds in the U.S.: Fidelity Balanced Fund <http://fundresearch.fidelity.com/mutual-funds/summary/316345206>, T. Rowe Price Balanced Fund <http://corporate.troweprice.com/ccw/home.do>, and American Funds Balanced Fund <www.americanfunds.com>.

Each of these funds had teams of researchers coming to work each day to juggle their fund holdings, trying to make the best possible returns. But that all costs money, as you know. As a result, Kris beat each of them handily over the past five years by 11.3 percent, 6.68 percent, and 17.57 percent, respectively.

Will he beat all of them every year? Certainly not. But over time, he's likely to pull further and further ahead. Are there balanced funds in the U.S. that beat Kris's returns over the past five years? Sure there are. But we have no way of knowing which funds will beat Kris over the next five years, so Kris's smartest choice is to keep his balanced portfolio of indexes.

Figure 6.2 Indexed Portfolio Beats Balanced Funds (2006–2011): Source: Morningstar.com2

Where Vanguard makes things even easier

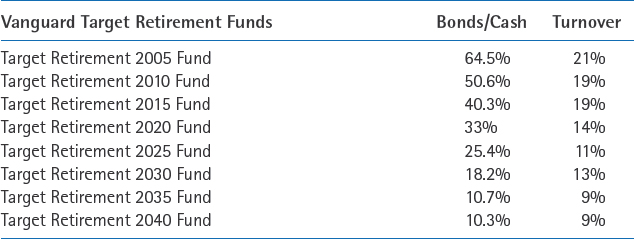

If the idea of spending 10 minutes a year rebalancing your portfolio is too much, Americans can opt for something even easier. Vanguard offers products called Target Retirement Funds, which offer a blended combination of stock and bond indexes. They're supposed to shift slightly more money into bonds as you get closer to retirement without the investor having to raise a finger to rebalance.

The funds are named based on your projected retirement date, but ignore the named date on the fund. For example, Kris would likely choose the Target Retirement 2015 Fund <https://personal .vanguard.com> because 40 percent of it is allocated toward bonds and Kris is now 40 years old. He isn't really planning to retire in 2015, but he would choose this fund because it has a bond allocation that matches his age.

Between January 2006 and January 2011, Vanguard's Target Retirement 2015 Fund gained 24.14 percent, a return that also beat each of the big three balanced funds found in Figure 6.2: Fidelity Balanced Fund, T. Rowe Price Balanced Fund, and American Funds Bala nced Fund.

What's more, if held in a taxable account, the Target Retirement Funds are much more efficient than most (if not all) actively balanced funds. In Table 6.1, you can see the respective “turnover” rates for each of the balanced funds we compared with Kris's account. And remember, the lower the turnover, the higher the tax efficiency.

An array of Vanguard's Target Retirement Funds, with their respective bond allocations and portfolio turnover rates is shown in Table 6.2. Remember not to get too concerned by the target date in the name. If you're a 50-year-old without a pension, it's wise to select a portfolio (or a fund, in this case) that has a bond allocation somewhat equivalent to your age. If, however, you're expecting to enjoy a generous pension upon retirement, you can afford to take greater risks by choosing a target fund with a lower bond component.

Table 6.1 Turnover Rate of Respective Funds

| Balanced / Target Retirement Funds | Taxable Turnover (the Lower, the Better) |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2015 Fund | 19% |

| Fidelity Balanced Fund | 122% |

| American Funds Balanced Fund | 46% |

| T. Rowe Price Balanced Fund | 41% |

Source: Morningstar.com3

Table 6.2 Turnover Rate of Vanguard's Target Retirement Funds

Source: Morningstar.com4

The United States is one of the easiest countries from which to build an investment account of indexes. And the options are rapidly growing for non-Americans as well.

Indexing In Canada—A Landscaper Wins by Pruning Costs

Originally from Rotorua, New Zealand, a beautiful city built at the bottom of an old volcanic crater, Keith Wakelin's family moved to British Columbia, Canada, when he was a teenager.

As a keen, long-distance runner, he made a name for himself as a tough competitor who has been racing toward finish lines for nearly four decades. When he was 42, he won Vancouver's bodydestroying 50-kilometer Knee Knackering Mountain Race in 2000. At 52, he's still a competitive force to be reckoned with.

Keith soon recognized that investing and distance running shared common ground. You can't carry excess weight if you want to be fast over long distances. And if you want to increase your odds of growing rich, you can't carry the burden of excess financial costs.

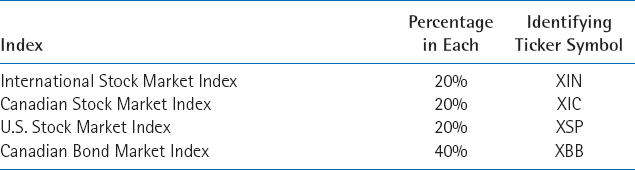

Wanting to diversify across all markets, Keith bought a total international stock market index, a Canadian stock market index, a U.S. stock market index, and a Canadian bond market index.

Table 6.3 The Global Couch Potato Portfolio

He simply followed MoneySense magazine's global couch potato performance concept, suggesting that you can split your money in the allocations as shown in Table 6.3. MoneySense tracks this portfolio online.5

At the end of each year, Keith looked at his account's allocation. Each of his indexes performed slightly differently. Taking a few minutes once a year, Keith rebalanced his account back to its original allocation.

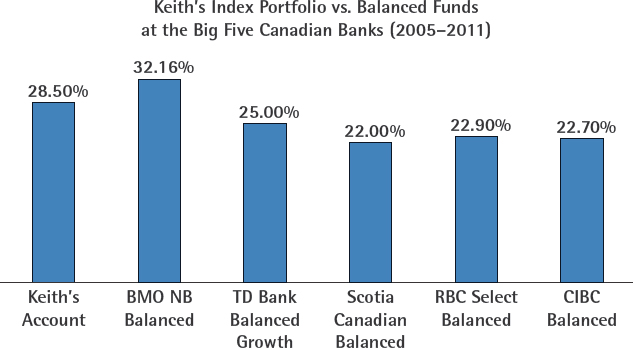

By selling off bits of the winners to add to the losers each year, Keith earned a total return of 28.5 percent (in Canadian dollars) from January 2005 to January 2011. This includes the drumming that the world's stock markets took in 2008–2009.5

How did Keith's portfolio stack up?

In Canada, there are five main banks, and they have the lion's share of the actively managed mutual fund business:

- Toronto Dominion Bank (TD Bank) <www.tdcanadatrust.com>

- Bank of Montreal (BMO) <www.bmo.com/home>

- Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC) <www.cibc.com>

- ScotiaBank <www.scotiabank.com>

- Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) <www.rbc.com>

The closest actively managed funds we have to Keith's portfolio (in terms of how the assets are placed) are with the “Balanced Funds” and each of the Canadian banks above has its Balanced flagship constituting both stocks and bonds.

Figure 6.3 Keith's Index Portfolio vs. Balanced Funds at the Big Five Canadian Banks (2005–2011): Source: Globeinvestor.com Fund Performances6

How did Keith's account perform compared with the banks?

Of the funds in Figure 6.3, the only one that beat Keith was the Bank of Montreal's NB Balanced Fund. Over a six-year period, Keith beat four out of five of Canada's most respected balanced mutual funds without even trying. Of course, there will be actively managed balanced funds that beat Keith over time, but there's no way of knowing which ones. Next year, for example, the Bank of Montreal Fund, which is in first place now, could find itself trailing all of the other funds. That's how it often works in the fund industry. There's only one thing for sure: Thanks to its low-fee structure, Keith's portfolio will outperform at least 90 percent of actively managed balanced funds. And if his money were held in a taxable account, he would extend his lead over the majority of Canada's actively managed funds.

How can Canadians invest like Keith?

If you want to invest like Keith, you have two low-cost options:

- You can buy the low-cost Toronto Dominion Bank Index Funds <www.tdcanadatrust.com/mutualfunds/tdeseriesfunds/index.jsp> (called e-Series Funds), which are—as of 2010—Canada's cheapest regular index funds. Or,

- You can open a discount brokerage account and buy Exchange Traded Index Funds.

Let's focus on the bank indexes first:

Toronto Dominion Bank currently has the most competitively priced index funds in Canada. But if you try walking into a bank and buying them, one of two things might happen to you:

- The bank representative might try convincing you to buy actively managed funds instead. Or,

- The representative might try selling you high-cost index funds. <http://www.tdcanadatrust.com/mutualfunds/tdeseriesfunds/> (Yes, TD Bank sells high-cost indexes as well, charging nearly twice as much as the indexes I recommend below.)

The low-cost indexes are called e-Series Funds and you can only purchase them online at <www.tdcanadatrust.com/mutualfunds/tdeseriesfunds/index.jsp>.7

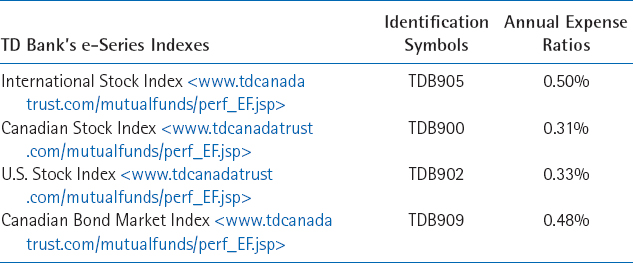

The TD bank e-Series index funds

Table 6.4 reveals that TD Bank's e-Series index funds cost an average expense ratio of just 0.4 percent annually, compared with more than 2.5 percent annually for the average Canadian actively managed fund.8 Canadian fund costs are reported to be higher than those in any other country, so it's best to avoid getting fleeced.9 If you want to invest using the global couch potato strategy with the cheap, e-Series funds, here they are with their respective identification symbols and hidden annual expense ratios.

Table 6.4 TD Bank's e-Series Fund Fees

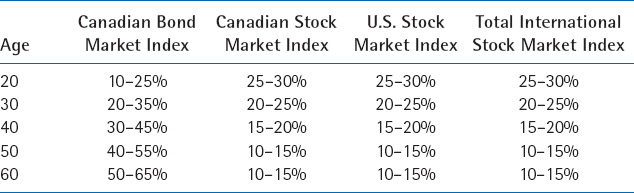

Table 6.5 Recommended Age-Related Portfolio Allocations for Canadians

You'll need a $100 minimum to open the account. If you want to automatically deposit a set amount into each index from your bank account, follow the online procedure. The minimum purchase for automatic deposits is $25 a month, and there are no fees associated with the account—except a two percent withdraw penalty if you sell within 90 days of opening the account.10

For the investor looking for low costs and convenience, these funds are the answer, and you can reinvest your dividends for free.

Remember that a good rule of thumb is to be consistent with your allocations. Choose a percentage for each index and balance it annually.

To blend the couch potato formula with the idea that a bond allocation should represent a person's age, I recommend that you choose one of these age-related breakdowns in Table 6.5.

Canadian indexed investing with exchange traded funds

When Keith first opened his indexed investment account, Toronto Dominion Bank didn't offer e-Series Index Funds. Instead, Keith built a portfolio of exchange traded funds (ETFs), which are index funds that are purchased off the stock market exchange using a brokerage firm.

Investing with ETFs might be worthwhile if you're not going to invest regularly in your account or if your account balance is fairly large.

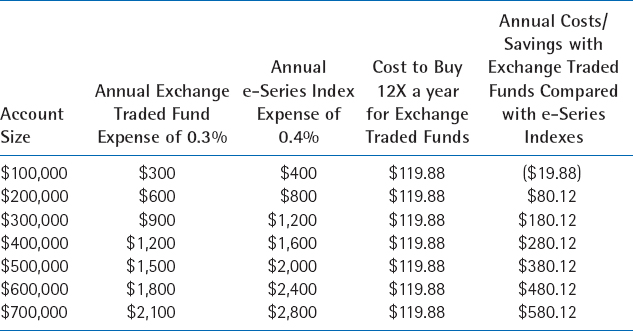

The costs associated with four exchange traded index funds (such as Keith owns) would amount to annual fees of 0.3 percent each year. This is slightly cheaper than TD bank's e-Series Funds, but the savings might not be worth the trouble. You can decide by weighing the relative size of your account with the savings.

On a $100,000 account, ETFs such as Keith's cost $300 a year in hidden expenses.

On a $100,000 account, e-Series indexes would cost $400 a year in hidden expenses.

The $100 annual savings on a $100,000 account wouldn't be worth the hassle if you were adding regularly to your account. Here's why:

If you invest every month, you'll have to pay a brokerage fee of $9.99 for each online purchase with ETFs (and more than that if your account value is below $100,000).

That monthly $9.99 adds up to nearly $120 a year. So if your account value doesn't easily exceed $100,000, you're better off with the e-Series Index Funds because they don't charge a commission to buy or sell.

Table 6.6 shows the costs associated with buying monthly e-Series indexes (which have higher expense ratios but no commission fees) versus buying exchange traded funds (which have lower expense ratios but charge purchase commissions)

Investing in ETFs does have a cost advantage once an investment account clears about $120,000, but it does require a bit more work on the part of the investor. Also, if the investor's account isn't well above $120,000 and if they make more than 12 purchases in a year, the cost savings can swing back in favor of the e-Series Funds. Note, from Table 6.6, that a $700,000 ETF account would save $580.12 a year compared with an e-Series indexed account, even after paying $9.99 a month ($119.88 a year) in annual commission fees.

Table 6.6 Total Costs of an ETF Portfolio vs. a TD Bank e-Series Portfolio

To purchase Exchange Traded Index Funds, an investor has to open a discount brokerage account. There are a variety of Canadian brokerage firms offering this service, including TD Waterhouse, <www.tdcanadatrust.com/easyweb5/start/tdw/get_started.jsp> CIBC's Investor's Edge, <www.investorsedge.cibc.com/ie/home.jsp> The Royal Bank Action Direct, <www.rbcdirectinvesting.com/> and Q-trade Investor <www.qtrade.ca/>.

Commission fees differ, but it's a competitive market and fees are falling. If you're still interested in ETFs and you want to buy like Keith, you'll have to purchase the following indexes off the Toronto Stock Exchange, via your brokerage. The initials before each respective index represent the code you'll need to enter (called a ticker symbol) before making each purchase.

- XIU = Canadian Stock Index

- XBB = Canadian Bond Index

- XIN = International Stock Index

- XSP = U.S. Stock Index

Whether you buy the e-Series index funds from TD Bank or whether you opt for brokerage-purchased ETF indexes, you'll beat the pants off the majority of the pros—just as Keith has.

Indexing in Singapore—A Couple Builds a Tiger's Portfolio in the Lion City

Singaporeans looking to invest in low-cost indexes might Google their options online. But like hidden vipers in the jungles of the Lion City, there are snakes in the financial service industry waiting to venomously erode your investment potential. Googling “Singapore Index Funds” will bring you to a company offering index funds that charge nearly one percent a year. That might seem insignificant, and that's exactly what marketers want you to believe. Paying one percent for an index fund can cost you hundreds of thousands of wasted dollars over an investment lifetime.

Singaporean index-fund retailer Fundsupermart <www.fundsupermart.com/main/home/index.svdo> flogs the Infinity Investment Series. It offers a S&P 500 Index Fund <www.fundsupermart.com/main/fundinfo/viewFund.svdo?sedolnumber=370283#charge> charging 0.97 percent annually (as an expense ratio) and they charge up to an additional two percent front-end sales fee to make the purchase.11

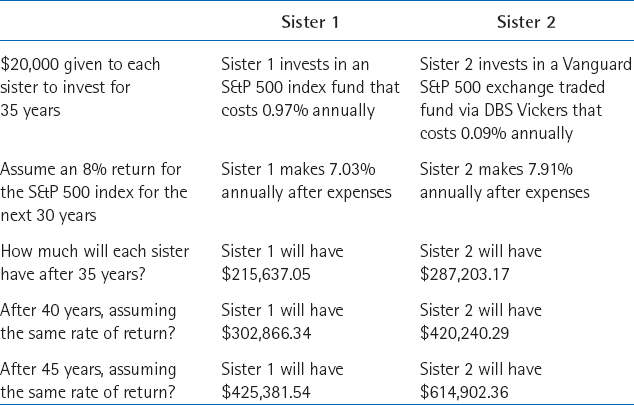

Let's assume that two Singaporean sisters decide to invest in a U.S. index. One of them buys the S&P 500 Index Fund through Fundsupermart while the other chooses to go with Vanguard's lowcost S&P 500 Exchange Traded Index Fund that charges just 0.09 percent annually, which they can buy through Singapore's DBS Vickers brokerage firm.12

Before fees, each fund would make the same return because they track exactly the same market. Costs, when presented in tiny amounts—like 0.97 percent—look minimal. But they're not. Table 6.7 shows how seemingly small fees can kill investment profits over a lifetime. If the U.S. S&P 500 index makes five percent a year for the next five years, an investor paying “just” 0.97 percent is giving away nearly 20 percent of her profits every year.

Table 6.7 Two Sisters Invest SGD$20,000

It's hard to imagine that, over 45 years, the true cost of such “small fees” can amount to more than a $180,000 difference on just a $20,000 investment. Costs matter, and you don't want the industry to fool you with small percentages.

Singapore residents embrace their indexing journey

Seng Su Lin and Gordon Cyr met in 2001 while volunteering at the Special Olympics in Singapore. Gordon teaches at Singapore American School and Seng Su Lin (who goes by Su) teaches technical writing at Singapore Polytechnic and at the National University of Singapore, while busily pursuing her PhD in psycholinguistics, the study of how humans acquire and use language.

The couple married in 2008, and Gordon (originally from Canada) looked over his investments with frustration. He explained his concerns:

“I used to teach in Kenya, and the school mandated that we invest our money with one of two companies. One of them was an offshore investment company called Zurich International Life Limited, <www.zurich.com/international/singapore/home/welcome.htm> headquartered on the Isle of Man. They invested in actively managed funds, but I started to feel cheated. Before opening the account, I clearly asked the representative if I could have control of how much or how little I was investing, and he said that I could. But after some time had passed, I wanted to stop contributing. The statements were really confusing. I couldn't see how much I had deposited over time and it was tough to see what my account was even worth.”13

Feeling uncomfortable, Gordon thought it would be easy to stop making his monthly payments to the company. But the Zurich representative (who no longer works for the firm) said Gordon had signed a contract to deposit a certain amount each month—and that he had to stick to it. Frustrated, Gordon pulled his money from Zurich, and was levied a heavy penalty for doing so.

Keen to take control of his money, Gordon opened an account with DBS Vickers <www.dbsvickers.com/Pages/default.aspx> in Singapore, to create a balanced, diversified account of Exchange Traded Index Funds similar to the “couch potato” formula that Keith Wakelin (our previously profiled Canadian) was following. The main difference was that Gordon didn't know where he and Su would eventually retire.

Su's family is in Singapore, Gordon's family is in Canada, and they own a piece of land in Hawaii. For that reason, Gordon thought it would be prudent to split his assets between Singaporean, Canadian and other global stock and bond markets. Here's what their portfolio of Exchange Traded Fund indexes looks like:

- 20 percent in the Singapore Bond index (Ticker Symbol A35)

- 20 percent in Singapore's Stock Market Index (Ticker Symbol ES3)

- 20 percent in Canada's Short-Term Bond Index (Ticker Symbol XSB)

- 20 percent in Canada's Stock Market Index (Ticker Symbol XIC)

- 20 percent in the World Stock Market Index (Ticker Symbol VT)

The first two indexes above trade on the Singaporean Stock Market; the following two trade on the Canadian Stock Exchange; and the last one, the World Stock Market Index, trades on the New York Stock Exchange. But you can purchase them all online using Singaporean brokerage firm DBS Vickers.

Gordon and Su rebalance their account with new purchases every month. For example, if the Singapore Bond Index hasn't done as well as the others, after a month it will represent less than 20 percent of their total investment. (Remember that they've allocated 20 percent of their account for each of the five indexes.) So when they add fresh money to their account, they would add to the Singapore Index. If the World Stock Index, the Canadian Stock Index, and the Singapore Stock Index have increased, leaving Gordon and Su with less than 40 percent in their combined bond indexes, then they would add fresh money to the bond indexes when making their next investment.

This ensures a couple of things:

- They're rebalancing their portfolio to increase its overall safety.

- They're buying the laggards, which over the long term will likely ensure higher returns.

If you are interested in following step by step instructions on how to buy Exchange Traded Index Funds in Singapore, you can access my website at the following: <http://andrewhallam.com/2010/10/singaporeans-investing-cheaply-with-exchange-traded-index-funds/>.

More Singaporeans are catching on

Always remember that the financial service industry's goal is to make money—for them, not for you. Not to miss the boat, Singaporeans are catching on to the benefits of low-cost investing.

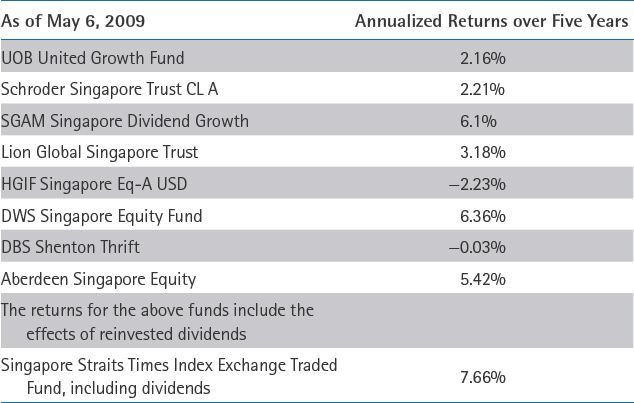

Financial blogger Kay Toh, at Moneytalk.sg, compared the Singapore Straits Times Index Exchange Traded Fund performance (May 6, 2004 to May 6, 2009) with the Singapore stock market unit trusts available through Fundsupermart. You can see the results of each of the funds in Table 6.8.

Table 6.8 Singapore Market Unit Trust Performances vs. Singapore Stock Market Index (May 6, 2004 to May 6, 2009)

Sources: Fundsupermart, Singapore Exchange, Streetracks14

Will some of the unit trusts have years where they beat the market index? Absolutely, but you don't know which ones will dominate and no one else does either.

Considering that no one can pick which unit trusts (actively managed funds) might outperform the indexes in the future, the educated investor doesn't bother with the gamble and follows Su and Gordon's lead: building portfolios with low-cost indexes.

Indexing in Australia—Winning with an American Weapon

Twenty-eight-year-old Australian, Neerav Bhatt, makes his living doing something few people could have imagined possible just a decade ago. He's a full-time blogger. Sitting behind a computer screen for most of the day, Neerav says he does a lot more reading than writing. Constantly on the lookout for inspiration, he devours online articles to spark his creative energy, often giving him something to comment on for his own blog.

His prolific reading exposed him to the superiority of index funds over actively managed mutual funds (known as unit trusts in Australia). “Most financial advisers are just salespeople. And people are far too trusting of them,” he says, explaining that most Australians just wander into a bank and buy their investment products, which generally charge nearly two percent a year in fees.

After first reading a newspaper article on index funds, Neerav investigated further by studying a copy of Princeton University Professor Burton Malkiel's classic book, A Random Walk Down Wall Street. Then, he discovered the American nonprofit investment company Vanguard, which had set up shop in his native Australia.

“Vanguard had been around for ages in Australia, but nobody was talking about it,” he said. And Neerav recognized why. Most people get their financial knowledge and education from advisers who make their living selling high-cost products. Vanguard's the thorn in the side of an investment-service community that wants to keep reaping as many fees as possible from unsuspecting investors.

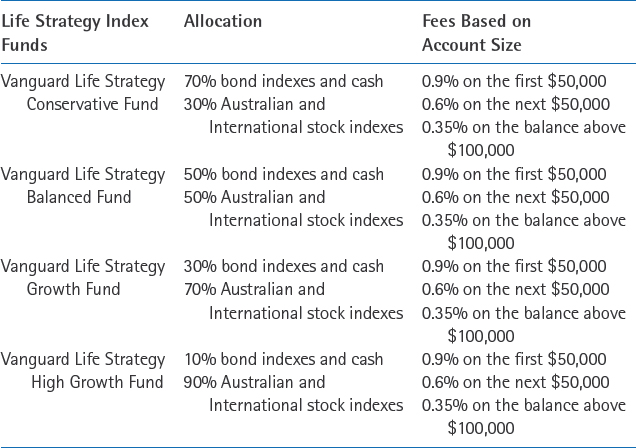

Neerav discovered that Australians can open accounts with Vanguard and they can usually transfer their superannuation to Vanguard as well.15 Vanguard offers individual indexes for the Australian markets and the international markets, but one of the more cost-effective ways of investing with Vanguard Australia is with its Life Strategy Funds. They're combinations of indexes, complete portfolios in a single fund, and the fee structure decreases as the account swells in value.

Alternatively, if they built a portfolio of separate index funds through Vanguard Australia, they could feasibly end up paying much higher overall fees. That's because the fee structure is determined on the size of each fund, not on the size of each account. The more money an investor has in each fund, the lower the percentage fee. So an investor with $200,000 could pay a lot less with a Vanguard Australian Life Strategy Fund than he or she would by building a portfolio with separate Vanguard indexes. Table 6.9 reveals the relative costs.

The fund you choose will depend on your tolerance for risk. If you're interested in an allocation of bonds that's close to your age, then you could choose from the following respective funds.

- Vanguard Life Strategy High Growth Fund: <www.vanguard.com.au/personal_investors/investment/managed-funds-upto-$500000/diversified/high-growth.cfm> 10 percent bonds, 90 percent stocks. This is well suited for high-risk investors or investors in their late teens or 20s.

Table 6.9 Vanguard Australia's Life Strategy Fund Options (Quoted in Australian dollars)

Source: Vanguard Investments Australia16

- Vanguard Life Strategy Growth Fund: <www.vanguard.com.au/personal_investors/investment/managed-funds-up-to$500000/diversified/growth.cfm> 30 percent bonds, 70 percent stocks. This benefits investors in their 30s and 40s.

- Vanguard Life Strategy Balanced Fund: <www.vanguard.com.au/personal_investors/investment/managed-funds-upto-$500000/diversified/balanced.cfm> 50 percent bonds, 50 percent stocks. Conservative younger investors or investors in their 50s and 60s might prefer the conservative nature of this fund, which still has capacity for growth with 50 percent allocated to stock indexes.

- Vanguard Life Strategy Conservative Fund: <www.vanguard.com.au/personal_investors/investment/managed-fundsup-to-$500000/diversified/conservative.cfm> 70 percent bonds, 30 percent stocks. Retirees or extremely conservative investors might find this fund to be the right fit.17

Another word about risk

Investors with a corporate or government pension might not feel the need to invest so conservatively. for example, a 50-year-old school teacher with a pension might prefer to buy the Growth Fund instead of the Conservative Fund. Over time, the Growth Fund will likely do better, but the volatility will be higher. If someone has a strong alternative source of retirement income, then they might want to take a higher risk/higher return option.

Neerav might be right when suggesting that most Australians are unaware of Vanguard. But one thing's for sure, there is economy in numbers. The more Australians who catch onto Vanguard, the cheaper its products will become.

The Next Step

Once you learn how to build indexed accounts, the time commitment you will spend on making investment decisions and transactions will be minimal. You could end up spending less than one hour a year on your investments.

Nobody is going to know how the stock and bond markets will perform over the next 5, 10, 20 or 30 years. But one thing is certain: if you build a diversified account of index funds, you'll beat 90 percent of professional investors. In a taxable account, you'll do even better.

There's only one risk standing in the way of your investment success, and it's an ironic one. If you speak to an adviser at a financial institution, they will do their best to convince you to follow a highercost, less-effective option. In my next chapter, I'll reveal some of the tricks they use to keep investors away from index funds.

Notes

1 Morningstar.com, Rebalanced fund returns for Vanguard's U.S. total stock market index (VTSMX), Vanguard's international stock market index (VGTSX), and Vanguard's total bond market index (VBMFX) (2006–2011).

2 Morningstar.com, Fund returns for Fidelity Balanced (FBALX), T Rowe Price Balanced (RPBAX), and American Funds Balanced (ABALX) (2006–2011).

3 Morningstar.com, fund turnover rates.

4 Morningstar.com, fund turnover rates for Vanguard's Target Retirement Funds.

5 “Global Couch Potato Performance,” accessed January 10, 2011, http://www.canadianbusiness.com/my_money/investing/article.jsp?content=20070123_122259_5192&ref=related.

6 Globeinvestor.com Fund Performances.

7 Toronto Dominion Bank, e-Series index funds, accessed April 15, 2011, http://www.tdcanadatrust.com/mutualfunds/tdeseriesfunds/index.jsp.

8 Ibid.

9 Ajay Khorana, Henri Servaes, and Peter Tufano, “Mutual Fund Fees Around the World,” The Review of Financial Studies 2008 Vol. 22, No. 3 (Oxford University Press) accessed April 15, 2011, http://faculty.london.edu/hservaes/rfs2009.pdf.

10 Toronto Dominion Bank, e-Series index funds, accessed April 15, 2011, http://www.tdcanadatrust.com/mutualfunds/tdeseriesfunds/index.jsp.

11 Infinity S&P 500 Index Fund Costs, accessed January 10, 2011, http://www.fundsupermart.com/main/fundinfo/viewFund.svdo?sedolnumber=370283#charge.

12 Vanguard S&P 500 Exchange Traded Fund Cost, accessed January 10, 2011, http://finance.yahoo.com/q/pr?s=SPY+Profile.

13 Personal Interview with Gordon Cyr, October 18, 2010, in Singapore.

14 Fundsupermart.com for actively managed Singapore market unit trust performances, accessed May 2009, http://www.fundsupermart.com/main/home/index.svdo; Singapore exchange traded fund historical prices, accessed May 2009, www.sgx.com; Historical dividends for Singapore market ETF: Streetracks.com, accessed May 2009, http://www.streettracks.com.sg/ssga/jsp/en/AnnualReport.jsp.

15 Vanguard Australia, Life Strategy Funds and Fees, accessed November 1, 2010, http://www.vanguard.com.au/personal_investors/investment/managed-funds-up-to-$500000/diversified/diversified_home.cfm.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.