RULE 9

The 10% Stock-Picking Solution . . . If You Really Can't Help Yourself

Women might be better investors than men. Various studies around the globe comparing investment account returns for both men and women put women on top.1 Why is this? Putting women on the household investment podium doesn't make sense to a lot of men. After all, the fairer sex isn't as likely to gather around the water coolers at work, talking up the latest hot stock or mutual fund. They're not as likely to be drooling over CNBC's Becky Quick as she and her co-hosts spout off about stocks, the economy, and the markets on a daily basis. How can women's investment results beat men's results if there are fewer women taking advantage of all the ever-changing information out there?

Finance professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean suggest that women's investment returns beat men's returns, on average, by roughly one percentage point annually because they trade less frequently, take fewer risks, and expect lower returns, according to a 2009 article by Jason Zweig in The Wall Street Journal.2 Overconfidence, it appears, might be more of a male trait than a female's.

When I've given seminars on indexed investing, many of the women learn to put together a diversified portfolio of indexes. But what has been the greatest risk to their indexed accounts, from what I've seen? Their husbands.

Men more often run the risk of imploding their investment accounts, of chasing get-rich-quick stocks, of trying to second-guess the economy's direction, and of feeling they can take higher risks to gain higher returns.

It sets up the potential for a matrimonial investment war, which might involve the need to compromise. Whether you are a man or a woman, if you really can't refrain from buying individual stocks, then set aside 10 percent of your investment portfolio for stock picking while keeping the remaining 90 percent in a diversified basket of indexes.

When buying individual stocks, do it intelligently. You're not likely to beat the indexes over the long term, but you're sure to have the odd lucky streak, and you might really enjoy the process.

Using Warren Buffett

In 1999, I joined a group of fellow school teachers who pooled some of their money into an investment club. We started out as a rudderless boat. Thinking we were smart, we watched the economic news, subscribed to stock-picking newsletters, followed financial websites, read The Wall Street Journal and listened to “experts” on television. And like most people who follow the manic depressive, schizophrenic news of the investment media, our account got hammered.

But then we became Warren Buffett disciples. Unlike the other stock market “gurus” we previously followed, Buffett never claims to know where stock prices are going to go over the short term. Nor does he pontificate about future interest rates or whether a certain company is going to report stronger-than-expected profit earnings that month, quarter, or year.

What he does give us, however, is far more valuable. He teaches how to think clearly and logically about buying businesses at rational prices, suggesting that a business has an intrinsic value and that valuation could always be higher or lower than what the stock market is quoting. In other words, a stock could be worth much more than its current market price. Finding great businesses at fair prices—or better yet, at great prices—is how Buffett has made a fortune in the stock market over time, and our investment club hoped to do the same.

Investment club follows the sage

By the end of 2000, after a rough start, our investment club of school teachers was officially following the Gospel of Warren. We selected stocks based on Buffett-like criteria and we've done well, averaging 8.3 percent annually from October 1999 to January 2011.

In 2004, I began showing our investment holdings and results to Ian McGugan, then editor of MoneySense. In 2008, he suggested we “go public” with the story, and I wrote about the club's results and methodology in the November 2008 issue of the magazine.3

Since 2008, our club's investments have continued to perform well. But here's the most important part: we don't have any illusions that we will beat the stock market indexes over the long haul. Time has an eroding effect on anyone bold enough to consider beating an index. Loads of smarter investors than us have outperformed the market for a number of years, only to be force-fed a piece of humble pie when they've made a wrong move. Lance Armstrong, the seven-time winner of the Tour De France, wasn't able to keep winning the world's greatest race—as much as he wanted to. And most investors (no matter how they might initially dominate) eventually get spanked by a diversified portfolio of indexes. For that reason, all of my retirement money is tucked away in indexes. That said, if you're still tempted to battle the stock market indexes yourself, let me share what lessons we have learned. Just remember this: no matter what kind of early results you achieve, don't get romanced by the notion that it's going to be easy to beat the market—and don't allocate more than a small portion of your portfolio to individual stocks.

Commit to the Stocks You Buy

I don't believe most millionaires trade stocks. If they own any shares at all, I believe they buy and hold them for long periods, much like they would if they bought a business, an apartment building, or a piece of land. Numerous international studies have shown that, on average, the more you trade, the less you make after taxes and fees.4 So forget about the high-flying, seductive rants and quacks on CNBC's financial program Squawk Box, convincing you to react to any market hiccup. Forget about fast-paced online newsletter pontifications touting the next hot sector or trading method. Most rich people are committed to their businesses. After all, stocks are businesses, not ticker symbols online. They should be purchased with care and held for years.

Two things you need to have

There are a couple of things that individual stock investors should master. For starters, they need to understand that when stock prices are falling, this is a good thing. Secondly, they need to learn how to identify a great business when they see it.

Hopefully, after reading Chapter 4, you'll have the first part licked. A rising market is a pain in the backside for a long-term investor. If you're going to be buying stock market investments for at least the next five years, you'll prefer to see a stagnating market, or better yet, a falling one. When you've selected a great business, and when the market sends that business into a spiral, you will celebrate and buy more of it. That's what we've done with the investment club. If we choose a solid business, the odds of its eventual recovery are high and short-term market fears let us take advantage of irrational prices.

So How Do You Identify a Great Business?

The first thing you need to know is what you don't know. Bear with me on that paradox. Defining what you don't know can keep you from falling into the black hole of investing. Understanding what a business makes and how much money it generates in sales isn't enough. You need a strong knowledge of how the company works. Obviously, you will never know everything about an individual company. Investors in individual stocks always need to take a leap of faith, but it's much better to understand as much as you can about a business you've elected to buy.

Even when a stock is really popular—such as the current technology favorite Apple <www.apple.com> —if you don't intimately understand the business it's important that you don't buy the stock.

This is the reason our investment club hasn't invested in Apple shares. There's no doubt that it's an amazing business, but we don't know enough about Apple. We don't understand how it plans to keep its competitive advantage. We do know that it was practically a dead company in 2001, and we know that today it's a darling business thanks to trendy, easy-to-use products that have taken the world by storm, but we can't tell you exactly how the business works. We can't tell you what it is developing and why. We can't tell you what big visions it has for its future, and we can't tell you whether those visions will materialize. Most importantly, we can't tell whether it will continue to sell the world's most popular products a decade from now. Maintaining its popularity and technological advantage is imperative to its success. And because we can't gauge how well it can do that in the future, we're not (and probably never will be) qualified to buy Apple stock.

You might be shaking your head as you hear my confession. Perhaps Apple runs within your circle of competence. Perhaps you work in the industry and you have a strong grasp on Apple's products, its future, and its internal finances. If that's the case, then fabulous. You might be fully capable of purchasing and holding Apple as an intelligent investor and business owner. But if you're technologically challenged (like I am) you might want to find more suitable investment waters to wade in.

Simple Businesses Can Ensure More Predictable Profits

The famous U.S. stock picker, Peter Lynch, who led Fidelity's Magellan fund <http://fundresearch.fidelity.com/mutual-funds/summary/316184100> to superb returns in the 1980s, once suggested that you should buy a business that any idiot can run, because one day an idiot will be running it.5This is the way it works in business. You won't always have fabulous leaders at the helm of your favorite companies. For that reason, my investment club has always preferred businesses that are simple rather than those that are rapidly changing.

Businesses that change rapidly are complicated, and they're tough for outside investors to analyze. What's more, they're usually more expensive than other businesses. Microsoft's Bill Gates suggests that tech companies should actually be cheaper than old economy businesses, because of their unpredictability. (Old economy refers to older blue-chip industries.) But they aren't. Speaking to business students at the University of Washington in 1998, he said: “I think the [price to earnings] multiples of technology stocks should be quite a bit lower than the multiples of stocks such as Coke and Gillette because we [those running technology companies] are subject to complete changes in the rules.”6

What will a technology business be doing in the future? Will it be bigger? Smaller? Or will it be extinct?

What's a Price-Earnings Ratio?

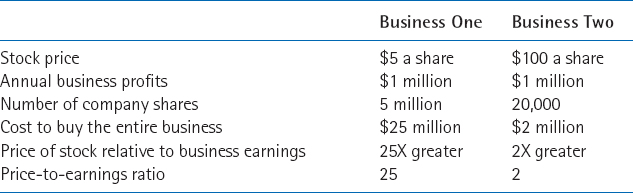

A price-earnings ratio (P/E ratio) indicates how cheap or expensive a stock is. The quoted price of a stock, alone, is irrelevant. For example, a $5 stock can be more expensive than a $100 stock.

Here's an example outlined in Table 9.1. Imagine two businesses, each generating $1 million in business profits each year.

Business One is comprised of 5 million shares at $5 each. So if you were to buy the entire company, it would cost $25 million ($5 a share × 5 million shares = $25 million).

If the company's business earnings are $1 million a year and if the price for the entire company is $25 million (at $5 a share), then we know that the price of the company is 25 times greater than the firm's annual earnings.

When a stock trades at a price that's 25 times greater than its annual profits, we can say the stock's P/E ratio is 25.

Imagine Business Two making annual profits of $1 million as well, with shares valued at $100 each on the stock market.

Assume that the business is comprised of 20,000 shares. To buy every share, thereby owning the entire business, would cost $2 million (20,000 shares × $100 per share = $2 million).

Table 9.1 When a $5 Stock Costs More Than a $100 Stock

Because the company also generates $1 million in business earnings, we can see that, at $2 million for the entire business, it's trading at two times earnings, for a P/E ratio of two.

Therefore, Business One is far more expensive than Business Two.

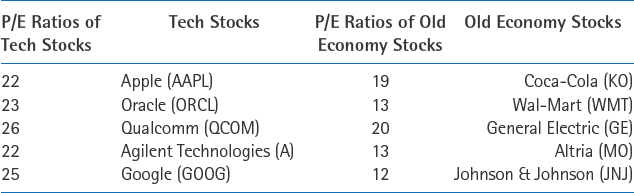

When you look at today's technology companies compared with old economy businesses, you can see that the investor in tech stocks takes two types of risks:

- They're buying businesses with low levels of future predictability.

- They're buying businesses that are more expensive. See examples in Table 9.2.

You can find tech companies with occasionally lower P/E ratios than older economy companies, but generally people are willing to pay higher prices for the rush of owning tech stocks—even though, as an aggregate, they tend to produce lower returns than old economy stocks when all dividends are reinvested.

Table 9.2 Comparative P/E Ratios as of January 2011

Source: Yahoo! Finance, price-to-earnings ratios as of January 20117

In Jeremy Siegel's enlightening book, The Future for Investors—Why the Tried and True Beats the Bold and New, the Wharton business professor concludes an exhaustive search indicating that when investors reinvest their dividends, they're far better off buying old economy stocks than new economy (tech) stocks. Dividend payouts for old economy stocks tend to be higher, so when reinvested, they can automatically purchase a greater number of new shares. New shares automatically purchased with dividends means that there are now more shares to gift further dividends. The effect snowballs. This is the main reason Siegel found that history's most profitable stocks over the past 50 years have names such as Exxon Mobil <www.exxonmobil.com/Corporate>, Johnson & Johnson <www.jnj.com>, and Coca-Cola <www.coca-cola.com>, instead of names such as IBM <www.ibm.com> and Texas Instruments <www.ti.com >.8

Most investors don't realize this. They're willing to pay more for the sexiness of high-tech stocks, which is one of the reasons most patient investors in old economy stocks tend to easily beat most tech stock purchasers over the long haul.

Stocks With Staying Power

Because you can't control a business's management decisions, you should pick stocks that are long-standing leaders in their fields.

One of my investment club's best purchases was Coca-Cola in 2004. We had the good fortune to buy it at $39 a share and were confident that we were getting a great business at a fair price. The stock price, however, has risen 72 percent since then, dampening our enthusiasm for additional shares based on a higher P/E ratio. The reason I call it one of our best purchases is because of its durable competitive advantage, coupled with the price we paid and the near inevitability of this company making far greater business profits 20 years from now. We feel confident that we won't have to watch Coca-Cola's business operations every quarter—that the business is nearly certain to generate higher profits 5 years from now, 10 years from now, even 20 years from now. Coca-Cola, after all, has a longstanding history of making more and more money. If we take its historical business earnings and divide them into three-year periods, we can see how consistently the company continues to grow. Table 9.3 shows Coca-Cola's earnings per share data since 1985.

Table 9.3 Coca-Cola's Consistent Profit Growth

| Three-Year Periods | Average Earnings Per Share |

| 1985–1987 | 26 cents |

| 1988–1990 | 43 cents |

| 1991–1993 | 72 cents |

| 1994–1996 | $1.19 |

| 1997–1999 | $1.45 |

| 2000–2002 | $1.57 |

| 2003–2005 | $2.06 |

| 2006–2008 | $2.65 |

| 2009–2010 | $3.21 |

Source: Value Line Investment Survey: Coca Cola9

Any way you slice it, emerging markets are helping to fuel even higher profits for Coca-Cola. The case volume of sales in India, for example, reported in Coca-Cola's 2010 annual report, reveals a 17 percent increase from the year before, and the Southern Eurasia region reported 20 percent case volume growth in 2010 from a year earlier.10 Coca-Cola could continue to be one of the world's most predictable businesses in the future, thanks to its wide (and growing) customer base, its myriad of drinks under its label, and its strong competitive position.

That said, there's a lot more to valuing a good business than figuring out if it will still have a competitive advantage years from now.

Buy businesses that increase the price of the products they sell

You've probably already gathered that the investment game is like playing odds. There's only one guarantee: invest in a low-cost index fund and you'll make the return of that market plus its dividends, and you'll beat the vast majority of professional investors over time. It's not foolproof; we have no idea where the markets will be five or ten years from now. Still, it's the closest thing we have to a stock market guarantee.

Picking individual stocks is a lot more treacherous. So how do you put the odds of success in your favor?

Buy businesses that are relatively easy to run and make sure the price of those business products are going to rise with inflation. An example of a business that doesn't meet those criteria is U.S. computer maker Dell. It's a fabulous company, but it's cursed by falling prices for its computer products. Most technology companies, after all, end up selling their products at lower prices over time. Think about how much it cost for your first laptop computer and how much cheaper (and better) laptops are today. It's getting cheaper for companies such as Dell to make their computers (which is one reason for their lower product prices), but lowering product prices can put a strain on profit margins. In other words, when Dell sells a $1,000 computer, after taxes and manufacturing-related costs, how much money does Dell pocket? From 2001 to 2005, Dell's average net profit margin was 6.34 percent. The company reaped an average of $63.40 for every $1,000 sold. And from 2006 to 2010, Dell's average profit margin was 4.08 percent—providing just $40.80 for every $1,000 of products that were sold.11

Lowering product prices threatens the company's long-term profitability, making it tough for the business to record the same kind of future profits without continually pushing itself to create something better every year (a concern PepsiCo and Coca-Cola don't need to worry about as much). If you put yourself in a cryogenic chamber and woke up 20 years from now, would Dell be a household computer name? It could be, or then again, it might bite the dust like so many tech companies before it.

In contrast, businesses such as Coca-Cola, Johnson & Johnson, and PepsiCo <www.pepsico.com> are far more likely to be market leaders in 20 years. Unlike technology-based businesses, these companies increase the prices of the products they sell partly because of consumer loyalty for their brands. They don't have as much pressure to keep coming up with “the next great product” unlike most technology-based businesses. They can create a product, market it, and expect people to enjoy it many years into the future. That's not the case with tech companies, which eventually have to slash the prices of their products to attract buyers who may otherwise be attracted to a competitor's newly introduced tech gadget, creating a much tougher (and arguably more competitive) business environment.

Learn to love low-debt levels

History is full of periods of economic duress—as well as economic prosperity. And the future will have its fair share of each.

Many professional stock pickers like businesses with low debt because they can weather economic storms more effectively. It makes sense. If fewer people are buying a company's product due to an economic recession, then the high-debt business is going to suffer. Money they've borrowed will still saddle them with interest payments, and they will likely be forced to lay off employees or sell assets (manufacturing equipment, buildings, and land) to meet those payments. Even if they have a fairly durable competitive advantage in their field, if they have to sell off too many assets, they probably won't maintain that advantageous position for long.

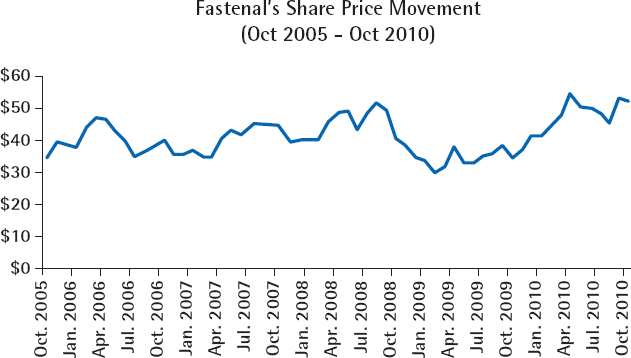

An example of a business without debt, which our investment club purchased in 2005, is Fastenal <www.fastenal.com>. The company sells building-supply materials and has successfully expanded its operation throughout the U.S. and beyond. But business slowed when a recession hit the U.S. in 2008, hammering the homeconstruction industry. Not having long-term debt, however, ensured it didn't have to meet the bank's loan requirements. If anything, the recession could end up being a good thing for a disciplined, debtfree or low-debt business. Such a company could acquire the assets of struggling businesses, making them even stronger when the recession ends.

You can see that investors have treated Fastenal's debt-free balance sheet with plenty of respect as well. During a slowdown for building-material suppliers, Fastenal's shares in late 2010 should have been priced a lot lower than they were five years ago when the U.S. housing market was in its full-bubbled boom.

But Fastenal's shares haven't struggled nearly as much as the company's counterparts. Figure 9.1 reveals that (as of January 2011) they were priced higher than they were five years previous at the height of the building boom.

Some investors like to look at businesses' debt-to-equity ratio. In others words, how much debt does a company have relative to assets? That's fair enough. But I've always preferred choosing businesses (preferably) with no debt at all.

It's especially wise to give ourselves a margin of safety when it comes to company debt. Some people refer to “good debt” and “bad debt.” In the case of “good debt,” many figure that if a business can borrow money at eight percent, then make 15 percent on that borrowed money (within the business) then gain a tax credit on the loan's interest, it will come out ahead. The logic is sound. But if a company's revenue dries up during a recession, then the eight percent loan can loom over the company like the grim reaper.

Figure 9.1 Fastenal's Debt-Free Balance Sheet Gives Price Stability During Recession: Source: Yahoo! Finance12

But how much debt is too much? That probably depends on the business.

The debt-to-equity ratio has its limitations. In theory, the lower the debt is relative to assets (equity), the better. But I generally set a standard for my investments that doesn't involve a debt-to-equity comparison. After all, if a business has equity in manufacturing equipment, why would I want it selling its equipment to pay bank loans during tough times? That just shoots the money machine in the foot. The company needs its machinery (and its other assets) to generate revenue in most cases, so I wouldn't want it selling the very things it needs to create future sales. As a result, I ignore the comparison between debt and equity, preferring to see the company's debt-to-earnings comparisons instead.

For me, if the firm's annual net income (when averaging the previous three year's earnings) is higher than or very close to the company's debt level, then the company is conservatively financed enough for my tastes.

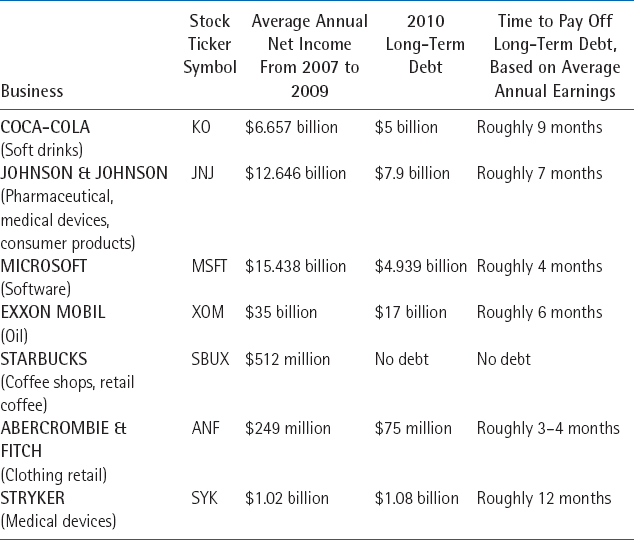

Figure 9.2 Sample of Businesses With Low Debt, Relative to Income: Source: Value Line Investment Survey13

Figure 9.2 lists a few well-known, global companies that fit my “conservatively financed” requirement.

Efficient businesses make dollars and sense

Think about this one from a logical business perspective. Imagine having the choice between buying two businesses that each generated net income averaging $1 billion over the past three years.

Assume that they're both growing their earnings at the same rate, and assume that they each have the same level of debt. They're also both in industries where the goods will likely be used for many years to come and each business can increase the price of its products with inflation. But there's a difference:

Business A generates its $1 billion profits off $10 billion in plants/machinery and other assets.

Business B generates its $1 billion profits off $5 billion in plants/machinery and other assets.

Which business are you going to be more comfortable with?

My answer would be Company B because it's more efficient. If it can generate $1 billion from $5 billion in assets/materials, then it has a return on total capital of 20 percent ($1 billion divided by $5 billion = 0.20)

Company A has a return on total capital of 10 percent because it generates profits that are only one-tenth the value of its assets. ($1 billion divided by $10 billion = 0.10)

Return on total capital measures how efficiently a business uses both shareholders' capital and debt to produce income. I believe the value of a company ultimately rests on its proven historical ability to earn a significant and reliable profit on the money that's invested in its business.

I recommend that any serious stock picker should order a subscription through investment-research provider Value Line, which gives you access to thousands of businesses around the world. And you can use its portfolio screens to figure out which companies have the highest rates of return on total capital and then narrow those down to see which businesses have been able to earn those returns consistently.

Looking for businesses with a high single year's return on total capital means little. If a company has a single great year, or if they're creative with their accounting, they could post a high return on capital that won't necessarily be sustainable as it goes forward. You want to look for durable businesses with long histories of efficiency.

As of October 2010, when I analyzed more than 2,000 businesses in the Value Line investment survey, fewer than 10 percent of them had returns on total capital exceeding 15 percent.

Refining the search further to find the percentage of businesses with a 10-year track record averaging 15 percent on total capital, I found only five percent of the 2,000-plus businesses fit the bill, including TJX Companies <www.tjx.com>, Weight Watchers <www.weightwatchers.com>, Garmin <www.garmin.com>, Colgate Palmolive <www.colgate.com>, Coach <www.coach.com>, Stryker <www.stryker.com>, Heinz <www.heinz.com>, Microsoft <www.microsoft.com>, Coca-Cola <www.coca-cola.com>, PepsiCo <www.pepsico.com>, Johnson & Johnson <www.jnj.com>, and Starbucks <www.starbucks.com>. By using Value Line's stock screen, you can find nearly 100 other businesses with 10-year track records that have averaged 15 percent or more on their total capital.

Demand honesty

Besides finding economically efficient businesses, it's also important for investors to seek businesses with honest managers. Executives should strive to be candid with shareholders and they should always think of enriching shareholders first, themselves second.

The most reliable way to find such management is to look for firms with a high level of insider ownership by top executives. If managers are shareholders themselves—especially if they own 10 percent or more of the stock—they're more likely to take shareholders' interests to heart.

You might think firms would have to be relatively small for insiders to own a high percentage of the shares, but that's not necessarily the case. Companies with more than 20 percent insider ownership include Netflix <www.netflix.com>, Papa John's International <www.ir.papajohns.com>, Nu Skin Enterprises <www.nuskin.com>, Berkshire Hathaway <www.berkshirehathaway.com>, Estee Lauder <www.esteelauder.com>, and the publisher of this book, John Wiley & Sons <www.wiley.com>, to name just a few.

If you really like a business, but it doesn't have a high percentage of insider ownership, you can look for other factors indicating the company puts shareholder interests first. One such factor is executive pay.

It's easy to find out online how much executives of publically traded companies get paid. Compare the company you're interested in with a few other businesses in the same industry. If the businesses make roughly the same amount of money, and the industry is the same, then their pay should be comparable. But if one chief executive officer's pay isn't in line with the others (by a wide margin), then you might have found a company that isn't putting its shareholder interests first.

Huge paychecks are just one symptom of questionable management. I also dislike companies that play games with their earnings to satisfy analysts. A prime example is the way some companies buy back shares. Doing so can make sense if management believes the shares are undervalued, therefore representing a good use of company money. But some companies turn this policy on its head, selling shares to raise money when the share price is cheap, then turning around and buying back shares when the markets are hot and shares are trading at ultra-expensive levels of 30 or 40 times their earnings. This insane ritual burns through a company's cash—essentially it consists of buying high and selling low—and the only motivation is the management's desire to fine-tune its earnings per share to satisfy the expectations of security analysts. Such games are maddening. They destroy shareholders' wealth.

Scuttlebutt like a detective

I've become a really big fan of online stock screens (such as Value Line) for narrowing down lists of businesses that meet selected, customized financial criteria, but for serious investors, stock screens are a starting point, not an ending point. The late Philip Fisher, author of Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits, devised a pre-Internet system of kicking the tires of companies that interested him by visiting the customers of the businesses he liked while questioning their competitors as well. He would ask great questions like: “What are the strengths and weaknesses of your competitors?” and “What should you be doing (but are not yet doing) to maintain your competitive advantage?”14

The key isn't to walk into a company's public relations department and ask these questions. It's to get in on the ground floor, where the products are being created, sold, or distributed, and ask there. The Internet can be a great source of information, but it can make people lazy, tempting us to skip getting a “hands-on” feel for our businesses.

When I see a residential construction site, for example, I often wander in and ask them what fastening construction brackets they're using. Simpson Manufacturing <www.simpsonmfg.com> is a business that my investment club owns shares in, and I'm always curious to see who's using the products, what they like about them, and what they dislike about them. If I wander onto construction sites and hear Simpson, Simpson, Simpson, and how easy the representatives are to work with, and how great the products are, then I've established ground-floor information that I might not necessarily find on the Internet.

As a business owner, I think it's very important to know your company well. Don't experiment with shortcuts; you could end up getting lost.

Set your price

Once you've decided which stocks look good, you have to get them at the right price. But what is a good price? Again, think of yourself as a business owner buying an entire company.

Let's take Starbucks as an example. As of this writing, it trades at $26 a share and there are 740 million shares in the company. That makes the entire business worth roughly $19.2 billion.

Over the past three years, its net income has averaged $598 million after posting profits of $672 million in 2007, $525 million in 2008, and $598 million in 2009.

If we owned the entire company, and if we paid $19.2 billion for it, we would want to know what our return on investment would be, annually, if we averaged $598 million a year in net profits.

When dividing $598 million by $19.2 billion, we get a return (also known as an earnings yield) of 3.1 percent.

It makes sense when thinking of it from a business sense. If you bought the entire business for $19.2 billion, and if you made $598 million after all expenses and taxes, you would have made 3.1 percent on your $19.2 billion.

Is that a good deal? It depends on the alternatives. You can start by comparing the yield from your stock with the yield on a 10-year government bond. No stock is as safe as government bonds since governments—at least those in highly developed countries —don't go bust. You would therefore be silly to take on the risk involved in buying a stock if it yields less than a risk-free bond. In fact, since future earnings on any stock are uncertain, you should make sure any shares you buy yield a bit more than the 10-year bond. The extra yield compensates you for the risk you're embracing in buying the stock.

How much yield you should demand is a matter of judgment. If a company has been growing rapidly, you may be willing to buy its stock when the average of earnings from the past three years works out to slightly more than the equivalent of a 10-year bond yield. On the other hand, if a firm is growing slowly, you might not want to buy its stock until you feel satisfied that it will provide you with at least a tenth more in earnings than a 10-year government bond. So if the bond were yielding, say, five percent, you would demand at least a 5.5 percent yield from the stock before you would be willing to purchase it.

Halfway through 2010, our club bought shares in the internationally ubiquitous company, Johnson & Johnson, at $57 a share. Over the past three years, its net income had averaged $12.64 billion, and when multiplying that by the number of shares in existence, you can calculate what it would cost to buy the entire company: roughly $160 billion. Dividing the average three-year net income ($12.64 billion) by the cost of the total company ($160 billion) gives us an annual earnings yield of 7.9 percent.15

When comparing that yield with a yield of a 10-year U.S. government bond (which paid 2.52 percent) I realized we were being well compensated for the added risk of owning the stock instead of a bond, so we bought shares in the company.

Selling Stocks

I think stockowners should hold their companies for long periods, but there are instances when it's wise to sell:

- If the company deviated from its core business.

- If the stock was grossly overpriced.

The first reason for selling is self-explanatory. If a company's ability to make chocolate is legendary, but it decided to switch gears to pursue space tourism (something it has no track record in) then it might be wise to bail on the shares.

The second reason to sell requires some judgment and a bit of math.

When we sold Schering Plough

Schering Plough (which can no longer be purchased on the stock market, since Merck <www.merck.com> purchased it in 2009) met my investment club's purchase requirements in 2003, and we paid $15.24 a share. Its blockbuster allergy medication, Claritin, was losing its patent protection, allowing other companies to be able to sell a generic version for a fraction of the cost. This was one of the reasons Schering Plough's price was hammered from about $40 a share in 2002 down to slightly more than $15 a share in 2003. I felt that Wall Street's reaction to the Claritin patent was overdone and highly emotional.

Table 9.4 Schering Plough's Earnings per Share

| Year | Schering Plough's Earnings per Share |

| 2001 | $1.58 |

| 2002 | $1.34 |

| 2003 | $0.31 |

Source: Value Line Investment Survey—Schering Plough 2005 Report16

Prior to the price drop, despite being a great business, Schering Plough hadn't interested me. Buying the stock at $40 a share would have been taking a huge risk because the earnings yield would have been just 3.8 percent. This was less than what a government bond was paying at the time, and there was the added risk of the looming Claritin patent expiration. Despite that risk, I certainly didn't expect Wall Street to hammer the stock all the way down to $15.

While we weren't attracted to Schering Plough at $40 a share (with an earning yield of 3.8 percent) we were much more interested when the earnings yield more than doubled.

The earnings levels for Schering Plough in the three years before we purchased shares can be seen in Table 9.4.

The average earnings for the previous three years represented $0.75 a share. At $15.24, that represented an earning's yield of seven percent. We bought our first shares and hoped, of course, the price would fall further.

By 2008, however, Schering Plough's price had risen to $25 a share, and the earnings yield based on the previous three years—2005, 2006, and 2007—gave the business an earnings yield of just 2005, 2006, and 2007—gave the business an earnings yield of just year government bond (which paid roughly four percent at the time) so we sold the shares at $25.17

A 64 percent profit over three years might sound impressive, but you also could view it as a disappointment. Investing is a lot easier if the businesses you buy (at good prices) grow at a pace relative to their earnings growth. Then, if the business doesn't deviate from its business model and if most of the reasons you bought the business in the first place still apply, you can keep holding the shares as they grow, long term, while earning healthy dividends along the way.

As I mentioned before, we rarely sell individual stocks, and to be honest, many of the stocks we have sold eventually went on to new highs without us. You could count Schering Plough as an example—Merck bought them out for $28 a share (12 percent higher than the company's stock price when we sold our shares).

Generally, the fewer trades you make in your investment account, the more money you'll make. Whether you're a mutual fund manager or a personal stock picker, lower trades equate to lower costs and taxes—and generally higher returns.

Committing to stocks for a long period of time, however, requires that you know as much about your companies as possible. To ensure the highest odds of familiarity, you may want to choose simple, predictable businesses, while opting for those that are efficiently run and likely to stand the test of time. Also consider what a financial tsunami could do to your businesses. Low-debt levels can be solid foundations—especially during tough times.

When you have found a business that you want to buy, analyze its price as if you were buying the entire business. The return you make can be highly dependent on the price you pay. But even with the best stock-picking tools, the odds are high that eventually most stock pickers will lose to market-tracking indexes, especially after factoring in transaction costs and taxes. It's fun to fight the tide. But you should invest the bulk of your money intelligently with a diversified account of indexes.

Notes

1 “Women Better Investors Than Men,” BBC News online, accessed April 16, 2011, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/4606631.stm.

2 Jason Zweig, “How Women Invest Differently Than Men,” The Wall Street Journal, May 12, 2009, accessed April 16, 2011, http://finance.yahoo.com/focus-retirement/article/107064/ How Women-Invest-Differently-Than-Men?mod=fidelity-buildingwealth.

3 Andrew Hallam, “How We Beat the Market,” MoneySense, November 2008, 44–48.

4 Paul Farrell, “Day-Traders Lose Big, Still Live in Denial: 77 percent of American Traders are ‘Losers’ While 82 percent of Day-Traders in Taiwan-China Are Bigger ‘Losers,’” Wall Street Warzone, June 16, 2010, accessed November 13, 2010, http://wallstreetwarzone.com/the-more-you-trade-the-less-you-earn/.

5 “The Greatest Investors: Peter Lynch,” Investopedia, accessed November 13, 2010, http://www.investopedia.com/university/greatest/peterlynch.asp.

6 Timothy Vick, How To Pick Stocks Like Warren Buffett (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001), 170–171.

7 Yahoo! Finance: Price to earnings ratios as of January 2011.

8 Jeremy Siegel, The Future For Investors, Why The Tried And True Triumph Over The Bold and New (New York: Random House, 2005), 7–9.

9 Value Line Investment Survey: Coca-Cola, January 28, 2011, accessed April 16, 2011, http://www3.valueline.com/dow30/f2084.pdf.

10 The Coca-Cola Company 2010 Annual Report, (http://www.thecoca-colacompany.com/investors/pdfs/form_10K_2010.pdf) 57.

11 Value Line Investment Survey: Dell, April 8, 2011.

12 Fastenal, historical price source, Yahoo! Finance, accessed April 16, 2011, http://finance.yahoo.com/q/hp?s=FAST&a=09&b=1&c=2005&d=09&e=17&f=2010&g=d.

13 The Value Line Investment Survey: 2011 reports for CocaCola, Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft, Exxon Mobil, Starbucks, Abercrombie & Fitch, and Stryker.

14 Philip A. Fisher, Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and Other Writings (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2003), 45.

15 Value Line Investment Survey: Johnson & Johnson, accessed April 16, 2011, http://www3.valueline.com/dow30/f4979.pdf.

16. Value Line Investment Survey: Schering Plough, 2008 Report.

17. Ibid.