RULE 3

Small Percentages Pack Big Punches

In 1971, when the great boxer Muhammad Ali was still undefeated, U.S. basketball star Wilt Chamberlain suggested publicly that he stood a chance beating Ali in the boxing ring. Promoters scrambled to organize a fight that Ali considered a joke. Whenever the ultraconfident Ali walked into a room with the towering Chamberlain within earshot, he would cup his hands and holler through them: “Timber-r-r-r-r!”

While Chamberlain felt that one lucky punch could knock Ali out and that he stood a decent chance in a fight, the rest of the sporting world knew better. Chamberlain's odds of winning were ridiculously low, and his bravado could only lead to significant pain for the great basketball player.

As legend has it, Ali's “Timber-r-r-r-r!” taunts eventually rattled Chamberlain's nerves to put a stop to the pending fight.1

Most people don't like losing, and for that reason there are certain things most of us won't do. If we're smart (sorry Wilt) we won't bet a professional boxer that we can beat him or her in the ring. We won't bet a prosecuting lawyer that we can defend ourselves in a court of law and win. We won't put our money down on the odds of beating a chess master at chess.

But would we dare challenge a professional financial adviser in a long-term investing contest? Common sense initially suggests that we shouldn't. However, this may be the only exception to the rule of challenging someone in their given profession—and beating them easily.

With Training, the Average Fifth Grader Can Take on Wall Street

The kid doesn't have to be smart. He just needs to learn that when following financial advice from most professional advisers, he won't be steered toward the best investments. The game is rigged against the average investor because most advisers make money for themselves—at their clients' expense.

The selfish reality of the financial service industry

The vast majority of financial advisers are salespeople who will put their own financial interests ahead of yours. They sell you investment products that pay them (or their employers) well, while you're a distant second on their priority list. Many of us know people who work as financial planners, and they're fun to talk to at parties or on the golf course. But if they're buying actively managed mutual funds for their clients, they're doing their clients a disservice.

Instead of recommending actively managed mutual funds (which the vast number of advisers do), they should direct their clients toward index funds.

Index funds—What experts love but advisers hate

Every nonfiction book has an index. Go ahead, flip to the back of this one and scan all those referenced words representing this book's content. A book's index is a representation of everything that's inside it.

Now think of the stock market as a book. If you went to the back pages (the index) you could see a representation of everything that was inside that “book.” For example, if you went to the back pages of the U.S. stock market, you would see the names of such listed companies as Wal-Mart, The Gap, Exxon Mobil, Procter & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive, and the directory would go on and on until several thousand businesses were named.

In the world of investing, if you buy a U.S. total stock market index fund, you're buying a single product that has thousands of stocks within it. It represents the entire U.S. stock market.

With just three index funds, your money can be spread over nearly every available global money basket:

- A home country stock market index (for Americans, this would be a U.S. index; for Canadians, a Canadian stock index)

- An international stock market index (holding the widest array of international stocks from around the world)

- A government bond market index (money you would lend to a government for a guaranteed stable rate of interest)

I'll explain the bond index in Chapter 5, and in Chapter 6, I'll introduce you to four real people from across the globe who created indexed investment portfolios. It was easy for them (as you'll see) and it will be easy for you.

That's it. With just three index funds, you'll beat the pants (and the shirts, socks, underwear, and shoes) off most financial professionals.

Financial Experts Backing the Irrefutable

Full-time professionals in other fields, let's say dentists, bring a lot to the layman. But in aggregate, people get nothing for their money from professional money managers . . . The best way to own common stocks is through an index fund.2

Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Chairman

If you were to ask Warren Buffett what you should invest in, he would suggest that you buy index funds. As the world's greatest investor, and as a man slowly giving away his fortune to charity, Warren Buffett's testimony is part of his pledge to give back to society. In this case, he's giving back knowledge: be wary of the financial service industry, and invest with index funds instead.

I don't believe I would have amassed a million dollars on a teacher's salary while still in my 30s if I were unknowingly paying hidden fees to a financial adviser. Don't think I'm not a generous guy. I just don't want to be giving away hundreds of thousands of dollars during my investment lifetime to a slick talker in a salesperson's cloak. And I don't think you should either.

What would a nobel prize-winning economist suggest?

The most efficient way to diversify a stock portfolio is with a low fee index fund.3

Paul Samuelson, 1970 Nobel Prize in Economics

Arguably the most famous economist of our time, the late Paul Samuelson was the first American to win a Nobel Prize in Economics. It's fair to say that he knew a heck of a lot more about money than the brokers suffering from conflicts of interest at your neighborhood Merrill Lynch, Edward Jones, or Raymond James offices.

The typical financial planner won't want you knowing this, but a dream team of Economic Nobel Laureates clarifies that advisers and individuals who think they can beat the stock market indexes are likely to be wrong time after time.

They're just not going to do it. It's just not going to happen.4

David Kahneman, 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics, when asked about investors' long-term chances of beating a broad-based index fund

Kahneman won the Nobel Prize for his work on how natural human behaviors negatively affect investment decisions. Too many people, in his view, think they can find fund managers who can beat the market index over the long haul.

Any pension fund manager who doesn't have the vast majority—and I mean 70% or 80% of his or her portfolio—in passive investments [index funds] is guilty of malfeasance, nonfeasance, or some other kind of bad feasance! There's just no sense for most of them to have anything but a passive [indexed] investment policy.5

Merton Miller, 1990 Nobel Prize in Economics

Pension fund managers are trusted to invest billions of dollars for governments and corporations. In the U.S., more than half of them use indexed approaches. Those who don't, are, according to Miller, setting an irresponsible policy.

I have a global index fund with all-in expenses at eight basis points.6

Robert Merton, 1997 Nobel Prize in Economics

In 1994, Merton, a University Professor Emeritus at Harvard Business School, probably thought he could beat the market. After all, he was a director of Long Term Capital Management, a U.S. hedge fund (a type of mutual fund I will explain in Chapter 8) that reportedly earned 40 percent annual returns from 1994 to 1998. That was before the fund imploded, losing most of its shareholders' money, and shutting down in 2000.7

Naturally, a Nobel Prize winner such as Merton is a brilliant man—and he's brilliant enough to learn from his mistakes. When asked to share his investment holdings in an interview with PBS News Hour in 2009, the first thing out of Merton's mouth was the global index fund that he owns, which charges just eight basis points.7That's just a fancy way of saying that the hidden annual fee for his index is 0.08 percent. The average retail investor working with a financial adviser pays between 12 to 30 times more than that in fees. These fees can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars over an investment lifetime. I'll show you how to get your investment fees down very close to what Robert Merton pays, learning from his mistakes.

More often (alas) the conclusions (supporting active management) can only be justified by assuming that the laws of arithmetic have been suspended for the convenience of those who choose to pursue careers as active managers.8

William F. Sharpe, 1990 Nobel Prize in Economics

If you were lucky enough to have Sharpe living across the street, he would tell you that he's a huge proponent of index funds and suggest that financial advisers and mutual fund managers who pursue other forms of stock market investing are deluding themselves.9

If a financial adviser tries telling you not to invest in index funds, they're essentially suggesting that they're smarter than Warren Buffett and better with money than a Nobel Prize Laureate in Economics. What do you think?

What Causes Experts to Shake Their Heads

Advisers get paid well when you buy actively managed mutual funds (or unit trusts, as they're known outside of North America) so they love buying them for their clients' accounts. Advisers rarely get paid anything (if at all) when you buy stock market indexes, and desperately try to steer their clients in another (more profitable) direction.

An actively managed mutual fund works like this:

- Your adviser takes your money and sends it to a fund company.

- That fund company combines your money with those of other investors into an active mutual fund.

- 3. The fund company has a fund manager who buys and sells stocks within that fund hoping that their buying and selling will result in profits for investors.

While a total U.S. stock market index owns nearly all the stocks in the U.S. market all of the time, an active mutual fund manager buys and sells selected stocks repeatedly.

For example, an active mutual fund manager might buy CocaCola Company shares today, sell Microsoft shares tomorrow, buy the stock back next week, and buy and sell General Electric Company shares two or three times within a 12-month period.

It sounds beneficially strategic, but academic evidence suggests that, statistically, buying an actively managed mutual fund is a loser's game when comparing it with buying index funds. Despite the strategic buying and selling of stocks by a fund manager for his or her fund, the vast majority of actively managed mutual funds will lose to the indexes over the long term. Here's why:

When the U.S. stock market moves up by, say, eight percent in a given year, it means the average dollar invested in the stock market increased by eight percent that year.10When the U.S. stock market drops by, say, eight percent in a given year, it means the average dollar invested in the stock market dropped in value by eight percent that year.

But does it mean that if the stock market made (hypothetically speaking) eight percent last year, every investor in U.S. stocks made an eight percent return on their investments that year? Of course not. Some made more, some made less. In a year where the markets made eight percent, half of the money that was invested in the market that year would have made more than eight percent and half of the money invested in the markets would have made less than eight percent. When averaging all the “successes” and “losses” (in terms of individual stocks moving up or down that year) the average return would have been eight percent.

Most of the money that's in the stock market comes from mutual funds (and index funds), pension funds, and endowment money.

So if the markets made eight percent this year, what do you think the average mutual fund, pension fund, and college endowment fund would have made on their stock market assets during that year?

The answer, of course, is going to be very close to eight percent. Before fees.

We know that a broad-based index fund would have made roughly eight percent during this hypothetical year because it would own every stock in the market—giving it the “average” return of the market. There's no mathematical possibility that a total stock market index can ever beat the return of the stock market. If the stock market makes 25 percent in a given year, a total stock market index fund would make about 24.8 percent after factoring in the small cost (about 0.2 percent) of running the index. If the stock market made 13 percent the following year, a total stock market index would make about 12.8 percent.

A financial adviser selling mutual funds seems, at first glance, to have a high prospect of getting his or her hand on your wallet right now. He or she might suggest that earning the same return that the stock market makes (and not more) would represent an “average” return—and that he or she could beat the average return through purchasing superior actively managed mutual funds.

If actively managed mutual funds didn't cost money to run, and if advisers worked for free, investors' odds of finding funds that would beat the broad-based index would be close to 50–50. In a 15-year-long U.S. study published in the Journal of Portfolio Management, actively managed stock market mutual funds were compared with the Standard & Poor's 500 stock market index. The study concluded that 96 percent of actively managed mutual funds underperformed the U.S. market index after fees, taxes, and survivorship bias.11

What's a survivorship bias?

When a mutual fund performs terribly, it doesn't typically attract new investors and many of its current customers flee the fund for healthier pastures. Often, the poorly performing fund is merged with another fund or it is shut down.

In November 2009, I underwent bone-cancer surgery—where large pieces of three of my ribs were removed, as well as chunks of my spinal process. But you want to know something? My five-year survivorship odds might be better than that of the average mutual fund. Examining two decades of actively managed mutual fund data, investment researchers Robert Arnott, Andrew Berkin, and Jia Ye tracked 195 actively managed funds, before reporting that the funds had a 17% mortality rate. According to the article they published with the Journal of Portfolio Management in 2000 called “How Well Have Taxable Investors Been Served in the 1980s and 1990s?” 33 of the 195 funds they tracked disappeared between 1979 and 1999.12 No one can predict which funds are going to survive and which won't. The odds of picking an actively managed fund that you think will survive are no better than predicting which bone-cancer survivor will last the longest.

When the Best Funds Turn Malignant

You might think that the very best funds (those with long established track records) are large enough and strong enough to have a predictable longevity. They can't suddenly turn sour and disappear, can they?

That's what investors in the 44 Wall Street Fund thought. It was the top-ranked fund of the 1970s—outperforming every diversified fund in the industry and beating the S&P 500 index for 11 years in a row. Its success was temporary, however, and it went from being the best-performing fund in one decade to being the worst-performing fund in the next, losing 73 percent of its value in the 1980s. Consequently, its brand name was mud, so it was merged into the Cumberland Growth Fund in 1993, which then was merged into the Matterhorn Growth Fund in 1996. Today, it's as if it never existed.13

Then there was the Lindner Large-Cap Fund, another stellar performer that attracted a huge following of investors as it beat the S&P 500 index for each of the 11 years from 1974 to 1984. But you won't find it today. Over the next 18 years (from 1984 to 2002) it made its investors just 4.1% annually, compared with the 12.6% annual gain for investors in the S&P 500 index. Finally, the dismal track record of the Lindner Large-Cap Fund was erased when it was merged into the Hennessy Total Return Fund.14

You can read countless books on index-performance track records versus actively managed funds. Most say index funds have the advantage over 80 percent of actively managed funds over a period of 10 years or more. But they don't typically account for survivorship bias (or taxes, which I'll discuss later in this chapter) when making the comparisons. Doing so gives index funds an even larger advantage.

When accounting for fees, survivorship bias, and taxes, most actively managed mutual funds dramatically underperform index funds. In taxable accounts, the average U.S. actively managed fund underperformed the U.S. Standard & Poor's 500 stock market index by 4.8 percent annually from 1984 to 1999.15

Holes in the hulls of actively managed mutual funds

There are five factors dragging down the returns of actively managed U.S. mutual funds: expense ratios, 12B1 fees, trading costs, sales commissions, and taxes. Many people ask me why they don't see these fee liabilities mentioned on their mutual fund statements. With the possible exception of expense ratios and sales commissions—in very small print—the rest are hidden from view. Buying these products over an investment lifetime can be like entering a swimming race while towing a hunk of carpet through the water.

1. Expense Ratios

Expense ratios are costs associated with running a mutual fund. You might not realize this, but if you buy an actively managed mutual fund, hidden fees pay the salaries of the analysts and/or traders to choose which stocks to buy and sell. These folks are some of the highest paid professionals in the world; as such, they are expensive to employ. There's also the cost of maintaining their computers, paying office leases, ordering the paper they shuffle, using electricity, and compensating the advisers/salespeople for recommending their funds.

Then there are the owners of the fund company. They receive profits based on the costs skimmed from mutual fund expense ratios. I'm not referring to the average Joe who buys fund units in the mutual fund. I'm referring to the fund company's owners.

A fund holding a collective $30 billion would cost its investors (the average Joe) about $450 million every year (or 1.5 percent of its total assets) in expense-ratio fees. That money is sifted out of the mutual fund's value, but it isn't itemized for investors to see.16 And the cash comes out whether the mutual fund makes money or not.

2. 12B1 Fees

Not every actively managed fund company charges 12B1 fees, but roughly 60 percent in the U.S. do. They can cost up to 0.25 percent, or a further $75 million a year for a $30 billion fund. These pay for marketing expenses including magazine, newspaper, television, and online advertising that's meant to lure new investors. That money has to come from somewhere. So current investors pay for new investors to join the party.17 It's like a masked phantom pulling money from the wallets of mutual fund investors every night. Financial advisory statements don't itemize these expenses either.

3. Trading Costs

A third fee includes the fund's trading costs, which fluctuate year to year, based on how much buying and selling the fund managers do. Remember, actively managed mutual funds have traders at the helm who buy and sell stocks within the fund to try and gain an edge. But on average, according to the global research company Lipper, the average actively managed stock market mutual fund accrues trading costs of 0.2 percent annually, or $60 million a year on a $30 billion fund.18 The costs of trading, 12B1 fees, and expense ratios aren't the only invisible albatrosses around the necks of mutual fund investors.

4. Sales Commissions

If the three hidden fees above are bringing you back in time to the nightmarish bottom of an elementary school dog pile, I have worse news for you. Many fund companies charge load fees: either a percentage up front to buy the fund (which goes directly to the salesperson) or a fee to sell the fund (which also goes directly to the salesperson). These fees can be as high as six percent. Many financial advisers love selling “loaded funds,” which add a pretty nice kick to their own personal accounts but they aren't such a great deal for investors. A fund charging a sales fee of 5.75 percent, for example, has to gain 6.1 percent the following year just to break even on the deposited money. That might sound like strange math at first, but if you lose a given percentage to fees, you have to gain back a higher percentage to get your head back above water. For example, losing 50 percent in one year (turning $100 into $50) ensures that you will need to double your money the following year to get back to the original $100. Advisers choosing loaded funds for their clients put a whole new spin on “Piggy Bank,” don't you think?

5. Taxes

More than 60 percent of the money in U.S. mutual funds is in taxable accounts.19 This means when an actively managed mutual fund makes money in a given year, the investor has to pay taxes on that gain if the fund is held in a taxable account. There's a reason for that. Actively managed stock market mutual funds have fund managers who buy and sell stocks within their funds. If the stocks they sell generate an overall profit for the fund, then the investors in that fund (if they hold the fund in a taxable account) get handed a tax bill at the end of the year for the realized capital gain. The more trading a fund manager does, the less tax efficient the fund is.

In the case of a total stock market index fund, there's virtually no trading. The gains that are made on the stocks held don't generate a taxable hit for the funds' investors unless the investor sells the fund at a higher price than he or she paid. Rather than paying a high rate of capital gains tax every year, the index investor is able to defer his or her gains, paying them when he or she eventually sells the fund. Doing so allows for significantly higher compounding profits.

Mutual fund managers know that few people are going to compare their “after-tax” results with other mutual funds. For example, a fund making 11 percent a year might end up beating a fund making 12% a year—after taxes.20 What makes one fund less tax efficient than another? It's the frequency of their buying and selling. The average actively managed mutual fund trades every stock it has during an average year. This is called a “100 percent turnover.”21 The trading practices of most mutual fund managers trigger short-term capital gains to the owners of those funds (when the funds make money). In the U.S., the short-term capital gain tax is a hefty penalty, but few actively managed fund managers seem to care.

In comparison, index-fund investors pay far fewer taxes in taxable accounts because index funds follow a “buy and hold” strategy. The more trading that occurs within a mutual fund, the higher the taxes incurred by the investor.

In the Bogle Financial Markets Research Center's 15-year study on after-tax mutual fund performances (from 1994 to 2009), it found actively managed stock market mutual funds were dramatically less tax efficient than a stock market index. For example, if you had invested in a fund (for your taxable account) that equaled the performance of the stock market index from 1994 to 2009, you would have paradoxically made less money than if you had invested in an index fund. But why would you have made less money if your fund had matched the performance of the stock index?

Before taxes, if your fund matched the performance of the U.S. index, you would have averaged 6.7 percent per year. After taxes though, for the actively managed fund to make as much money as a U.S. index fund, it would have needed to beat the index by a total of 16.2 percent over the 15-year period. This is assuming that the mutual fund manager bought and sold stocks with a regularity that equaled the average actively managed fund “turnover.” A post-tax comparison of a mutual fund's performance against the performance of a stock market index isn't something that you will likely see on a typical mutual fund statement.22 But in a taxable account, the post-tax gain is the only number that should count.

Adding high expense ratios, 12B1 fees, trading costs, sales commissions, and taxes to your investment is a bit like a boxer standing blindfolded in a ring and asking his opponent to hit him five times on the jaw before the opening bell. It's tough to put up a fair fight when you're already bleeding.

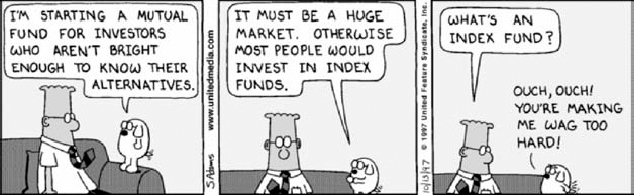

Figure 3.1 Dilbert's Take on Mutual Funds: Source: Dilbert Comics23

Figure 3.1 illustrates that if you learned this in school, it's likely that you would never consider investing in actively managed funds as an adult.

The futility of picking top mutual funds

You've just told your financial adviser that you'd like to invest in index funds—and now she's desperate. She won't make money (or not much) if you invest in indexes. It's far more lucrative for advisers to sell actively managed mutual funds instead. She needs you to buy the products for which she will be compensated handsomely, so here's the card she plays:

“Look, I'm a professional. And our company has access to researchers who will help me choose actively managed funds that will beat the indexes. Just look at these top-rated funds. I can show you dozens of them that have beaten the stock market index over the past 10 years. Of course I would only buy you top-rated funds.”

Are there dozens of funds that have beaten the stock market indexes over the past 5, 10 or 15 years? Sure there are. But those funds, despite their track records, aren't likely to repeat their winning streaks. Mutual fund investing is a rare example of how, paradoxically, historical excellence means nothing.

Reality Check

Morningstar <www.morningstar.com> is an investment-research firm in the U.S. that awards funds based on a five-star system: five stars for a fund with a remarkable track record, all the way down to one star for a fund with a poor track record. Five-star funds tend to be those that have beaten the indexes over the previous five or ten years.

The problem is that fund rankings change all the time, and so do fund performances. Just because a fund has a five-star rating today doesn't mean that it will outperform the index over the next year, five years, or ten years. It's easy to look back in time and see great performing funds, but trying to pick them based on their historical performance is an expensive game.

Academics refer to something they call “reversion to the mean.” In practical terms, actively managed funds that outperform the indexes typically revert to the mean or worse. In other words, buying the top historically performing funds can end up being the kiss of death.

If an adviser had decided to purchase Morningstar's fivestar rated funds for you in 1994, and if he sold them as the funds slipped in the rankings (replacing them with the newly selected five-star funds), how do you think the investor would have performed from 1994 to 2004 compared with a broad-based U.S. stock market index fund?

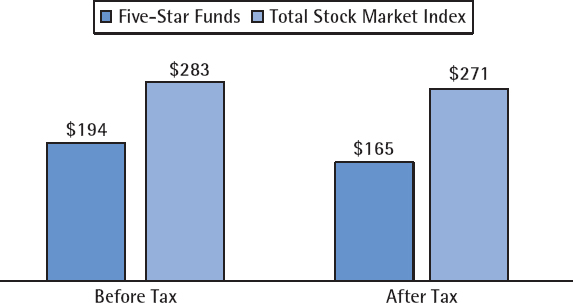

Thanks to Hulbert's Financial Digest, an investment newsletter that rates the performance predictions of other newsletters, we have the answer which is emphasized in Figure 3.2.

One hundred dollars invested and continually adjusted to only hold the highest rated Morningstar funds from 1994 to 2004 would have turned into roughly $194, averaging 6.9 percent annually.

One hundred dollars invested in a broad-based U.S. stock market index from 1994 to 2004 would have turned into roughly $283, averaging 11 percent annually.24

Figure 3.2 Five-Star Funds vs. Total Stock Market Index (1994–2004): Source: John C. Bogle, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing

If you add further taxable liabilities, the results for the Morningstar superfunds would look even worse. You might as well be running with a monkey on your back.

One hundred dollars invested and continually adjusted to only hold the highest rated Morningstar funds from 1994 to 2004 would have turned into roughly $165 after taxes, at 5.15 percent annually.

One hundred dollars invested in a broad-based U.S. stock market index from 1994 to 2004 would have turned into roughly $271 after taxes, at 10.5 percent annually.

Interestingly, more than 98 percent of invested mutual fund money gets pushed into Morningstar's top-rated funds25

But choosing which actively managed mutual fund will perform well in the future is, in Burton Malkiel's words: . . . “like an obstacle course through hell's kitchen.”26 Malkiel, a professor of economics at Princeton University and the bestselling author of A Random Walk Guide to Investing, adds:

There is no way to choose the best [actively managed mutual fund] managers in advance. I have calculated the results of employing strategies of buying the funds with the best recent-year performance, best recent two-year performance, best five-year and ten-year performance, and not one of these strategies produced above average returns. I calculated the returns from buying the best funds selected by Forbes magazine . . . and found that these funds subsequently produced below average returns.27

Still, most financial advisers won't give up. Their livelihood depends on you believing that they can do it, that they can find funds that will beat the market indexes.

Before we were married, my wife Pele was being “helped”by the U.S.-based financial service company Raymond James. <www.raymondjames.com/personal_investing/> She was sold actively managed mutual funds, and on top of the standard, hidden mutual fund fees, she was charged an additional 1.75 percent of her account value every year. An ongoing annual fee such as this—called a wrap fee, adviser fee, or account fee—is like a package of arsenic-laced cookies sold at your local health food store. Why did her adviser charge her this extra fee? Let's just say the adviser was servicing my wife the way the infamous Jesse James used to service train passengers—by taking the money and running.

According to a 2007 article published in the U.S. weekly industry newspaper Investment News, Raymond James representatives are rewarded more for generating higher fees:

In the style of a 401(k) plan, the new deferredcompensation program this year gives a bonus of 1% to affiliated [Raymond James] reps who produce $450,000 in fees and commissions, a 2% bonus for $750,000 producers, and 3% for reps and advisers who produce $1 million. After that, the bonus, which will affect about 500 of the firm's 3,600 reps, increases one percentage point for every additional $500,000 in production, topping out at 10% for reps who produce $3.5 million in fees and commissions. That pushes those elite reps' payout to 100%—or even more—of their production, according to the company.28

With pilfering incentives like these, salespeople and advisers make out like sultans.

Looking at my wife's investment portfolio in 2004, after tracking her account's performance, I calculated that her $200,000 account would have been $20,000 better off if she had been with an index fund over the previous five years, instead of with her adviser's actively managed mutual funds. In my calculation, I included the 1.75 percent annual “fleecing” fee her adviser charged, on top of the mutual funds' regular expenses.

When Pele asked her adviser about her account's relatively poor performance, he suggested some new mutual funds. When Pele asked about index funds, he dismissed the idea. Perhaps he had his eye on a big prize: a Porsche or an Audi convertible. He couldn't afford either if he bought his client index funds. So he switched her into a group of different actively managed funds that had beaten the indexes over the previous five years—all had Morningstar five-star ratings.

And how did those new funds do from 2004 to 2007? Badly. Despite the strong track records of those funds, they performed poorly, relative to the market indexes, after he selected them for Pele's account. So Pele fired the guy, and I married Pele.

Over an investment lifetime, it's a virtual certainty that a portfolio of index funds will beat a portfolio of actively managed mutual funds, after all expenses. But over a one-, three-, or even a five-year period, there's always a chance that a person's actively managed funds will outperform the indexes.

At a seminar I gave in 2010, a man I'll call Charlie, after seeing the returns of an index-based portfolio, said:“My investment adviser has beaten those returns over the past five years.”

That's possible, but the statistical realities are clear. Over his investment lifetime, the odds are that Charlie's account will fall far behind an indexed portfolio.

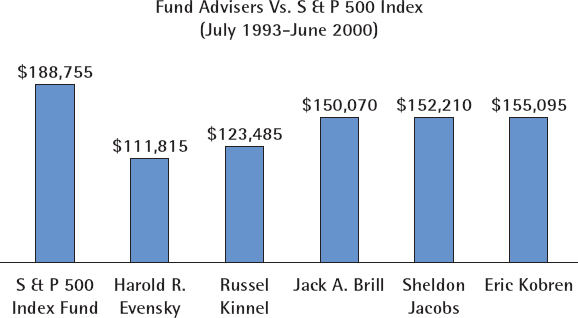

In July 1993, The New York Times decided to run a 20-year contest pitting high-profile financial advisers (and their mutual fund selections) against the returns of the S&P 500 stock market index.

Every three months, the newspaper would report the results, as if the money was invested in tax-free accounts. The advisers were allowed to switch their funds, at no cost, whenever they wished.

What started out as a great publicity coup for these high-profile moneymen quickly turned into what must have felt like a quarterly tarring and feathering. After just seven years, the S&P 500 index was like a Ferrari to the advisers' Hyundai Sonatas, as revealed in Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3 The New York Times investment Contest

An initial $50,000 with the index fund in 1993 (compared with the following respective advisers' mutual fund selections) would have turned into the preceding sums by 2000.29

Mysteriously, after just seven years, The New York Times discontinued the contest. Perhaps the competitive advisers in the study grew tired of the humiliation.

Finding help without a conflict of interest

I'll liken the average financial adviser to chocolate cake. Can following a decadent nutritional plan of sugary baked goods make you feel good? Sure, for about 30 seconds as your taste buds relish the sticky sweetness. But the average financial adviser is as good for your long-term wealth as a chocolate cake diet is to your longterm health.

That said, there are financial advisers who charge by the hour for objective advice. While no one wants to add another bill to the pile, a “fee-only” financial planner charging an hourly rate can be a professional partnership that helps you create a successful portfolio of index funds.

For Americans, there's an easy option. You can give your money to Vanguard, <www.vanguard.com> a U.S.-based, nonprofit financial service company that happens to be the world's largest provider of index funds. You pay a small fee of $250 a year, and an adviser working for Vanguard will help you invest your money. When your account exceeds $250,000, the service is free.

AssetBuilder <www.assetbuilder.com> is another option. Based in Texas, this company charges low fees to operate as a broker that purchases index funds through a group called Dimensional Fund Advisors <www.dfaus.com/>. The small annual percentage fee for the service allows you to wipe your hands clean of managing your money yourself.

The following companies also charge low fees to build accounts of index funds for U.S. clients: RW Investments <www.rwinvestmentstrategies.com/background.html> (based in Maryland), Aperio Group <www.aperiogroup.com/> (based in California), and Evanson Asset Management <www.evansonasset.com/> (based in California).

There are other companies offering similar services. But be careful. Not all “fee-only” businesses offer low-fat services.

Where hidden calories lie

The number of fee-only, certified financial planners is increasing in the U.S. But you have to be careful. Fee-based adviser, Bert Whitehead, says in his book, Why Smart People Do Stupid Things with Money, that there are many organizations (such as American Express) that offer supposedly fee-based services, charging a small fee for a consultation, but they actually stuff investment accounts with their own brand of actively managed mutual funds and insurance products.30 Actively managed mutual funds pad the coffers of investment service companies, so they are good for the businesses that sell you such products, but they're not good for you.

My hope, though, is that this book will give you every tool required to build portfolios of index funds yourself. Then you can hire a trustworthy accountant to provide advice on tax-sheltered accounts. Seeking an accountant's advice, you'll confidently avoid every conflict of interest corrupting the financial service industry—as long as your accountant doesn't sell financial products on the side.

For a review, however, let's take another look at total stock market index funds and actively managed mutual funds with a side-byside comparison.

Table 3.1 Differences between Actively Managed Funds and Index Funds

Global citizens and index funds

If you're British or Australian, you can follow the lead with Vanguard, which has already set up shop in your country. As a nonprofit group, it might be the world's cheapest financial service operator, and indexing is their specialty.

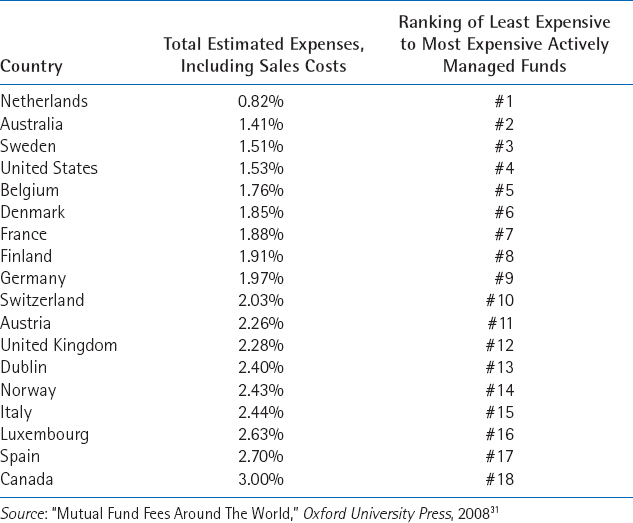

If you're from another country, or if you're a global citizen working overseas, there are indexing options available for you as well (which I will discuss in Chapter 6). As high as U.S. actively managed stock mutual fund costs can run, the average non-U.S. fund is even more expensive. In a study presented in 2008 by Oxford University Press, Ajay Khorana, Henri Servaes, and Peter Tufano compared international fund costs, including estimated sales fees. According to the study, the country with the most expensive stock market mutual funds is Canada. Fortunately, for Canadians, Vanguard is planning to extend its services to its long-suffering northern neighbors.

High global investment costs make it even more important for global citizens outside of the U.S. to buy indexes for their investment accounts, rather than pay the heavy fees associated with actively managed mutual funds.

Table 3.2 The World's Actively Managed Stock Market Mutual Fund Fees

Source: “Mutual Fund Fees Around The World,” Oxford University Press, 200831

Who's Arguing against Indexes?

There are three types of people who argue that a portfolio of actively managed funds has a better chance of keeping pace with a diversified portfolio of indexes after taxes and fees over the long term.

Introduced first, dancing across the stage of improbability is your friendly neighborhood financial adviser. Pulling all kinds of tricks out of his bag, he needs to convince you that the world is flat, that the sun revolves around the Earth, and that he is better at predicting the future than a gypsy at a carnival. Mentioning index funds to him is like somebody sneezing on his birthday cake. He wants to eat that cake, and he wants a chunk of your cake too.

He exits, stage left, and a bigger hotshot strolls in front of the captive audience. Wearing a professionally pressed suit, she works for a financial advisory public relations department. Part of her job is to compose confusing market-summary commentaries that often accompany mutual fund statements. They read something like this:

Stocks fell this month because retail sales were off 2.5 percent, creating a surplus of gold buyers over denim, which will likely raise Chinese futures on the backs of the growing federal deficit, which caused two Wall Street Bankers to streak through Central Park because of the narrowing bond yield curve.

Saying stock markets rose this year because more polar bears were able to find suitable mates before November has as much merit as the confusing economic drivel that financial planners write and distribute, assuming that nobody will read it anyway.

If you ask her, she will tell you that actively managed mutual funds are the way to go—but curiously doesn't mention she has killer mortgage payments on her $17 million, Hawaiian beachside summer home and you need to help her pay it.

Sadly, the third type of person who might tell you actively managed mutual funds have a better statistical long-term chance at profit (over indexes) are the prideful, or gullible folks who won't want to admit their advisers put their own financial interests above their clients.

Let's consider Peter Lynch, the man who was arguably one of history's greatest mutual fund managers. Before retiring at age 46, he managed the Fidelity Magellan fund <http://fundresearch.fidelity.com/mutual-funds/summary/316184100>, which captured public interest as it averaged 29 percent a year from 1977 to 1990.32 More recently, however, Lynch's former fund has disappointed investors, earning a total of just 21 percent over the past decade, compared with 41 percent with the S&P 500 index.33 Hammering the industry's faults, he says:

So it's getting worse, the deterioration by professionals is getting worse. The public would be better off in an index fund.34

As the industry's idol from the 1980s, you might suggest that Lynch is a relic of a bygone era. Perhaps. But let's turn our attention to the present, and look at Bill Miller, the current actively managed fund manager of the Legg Mason Value Trust <www.leggmason.com> In 2006, Fortune magazine writer Andy Serwer called Miller “the greatest money manager of our time,” after Miller's fund had beaten the S&P 500 index for the fifteenth straight year.35 Yet, when Money magazine's Jason Zweig interviewed Miller in July 2007, Miller recommended index funds:

[A] significant portion of one's assets in equities should be comprised of index funds . . . Unless you are lucky, or extremely skillful in the selection of managers, you're going to have a much better experience going with the index fund.36

Miller's quote was timely. Since 2007, his fund's performance has dramatically underperformed the total U.S. stock market index. Some mutual fund managers, of course (these are people who actually run the funds) are required by their employers to buy shares in the funds they run. But in taxable accounts, if fund managers don't have to commit their own money, they generally won't. Ted Aronson actively manages more than $7 billion for retirement portfolios, endowments, and corporate pension fund accounts. He's one of the best in the business. But what does he do with his own taxable money? As he told Jason Zweig, who was writing for CNN Money in 1999, all of his taxable money is invested with Vanguard's index funds:

Once you throw in taxes, it just skewers the argument for active [mutual fund] management . . . indexing wins handsdown. After tax, active management just can't win.37

Or, in the words of a real heavy hitter, Arthur Levitt, former chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission:

The deadliest sin of all is the high cost of owning some mutual funds. What might seem to be low fees, expressed in tenths of one percent, can easily cost an investor tens of thousands of dollars over a lifetime.38

You don't have to be disappointed with your investment results. With disciplined savings and a willingness to invest regularly in lowcost, tax-efficient index funds, you can feasibly invest half of what your neighbors invest—over your lifetime—while still ending up with more money.

You may not have learned these lessons in school, but they are vital to your financial well being:

- Index fund investing will provide the highest statistical chance of success, compared with actively managed mutual fund investing.

- Nobody yet has devised a system of choosing which actively managed mutual funds will consistently beat stock market indexes. Ignore people who suggest otherwise.

- Don't be impressed by the historical returns of any actively managed mutual fund. Choosing to invest in a fund, based on its past performance, is one of the silliest things an investor can do.

- Index funds extend their superiority over actively managed funds when the invested money is in a taxable account.

- Remember the conflict of interest that most advisers face. They don't want you to buy index funds because they (the brokers) make far more money in commissions and trailer fees when they convince you to buy actively managed funds.

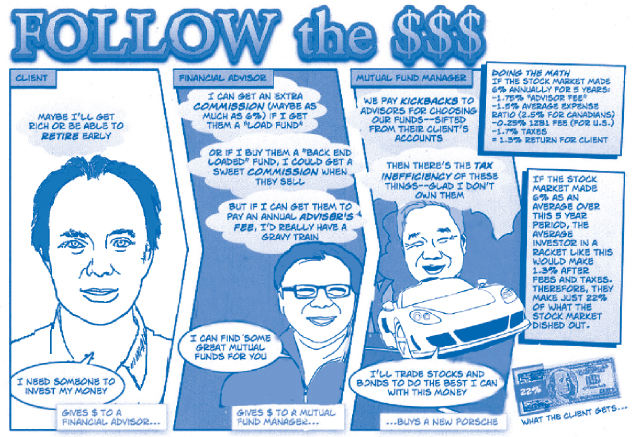

Clearly avoiding the pitfall illustrated in Figure 3.4 will precipitate a far more promising future.

Figure 3.4 A Financial Adviser's Conflict of Interest: Source: Fang Yang

Notes

1 W. Gregory Guedel. “Ali versus Wilt Chamberlain—The Fight That Almost Was,” EastSideBoxing, May 29, 2006, accessed October 20, 2010, http://www.eastsideboxing.com/news.php?p=7095&more=1http://www.eastsideboxing.com/news.php?p=7095&more=1.

2 Linda Grant, “Striking Out at Wall Street,” U.S. News & World Report, June 20, 1994, 58.

3. Mel Lindauer, Michael LeBoeuf, and Taylor Larimore, The Bogleheads Guide to Investing (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), 83.

4 “Investors Can't Beat the Market, Scholar Says,” Orange County Register, January 2, 2002, accessed October 30, 2010, http://www.ifa.com/Library/Support/Articles/Popular/KahnemanInvestorscantbeatmarket.htm.

5 Peter Tanous, “An Interview With Merton Miller,” Index Fund Advisors, February 1, 1997, accessed October 30, 2010, http://www.ifa.com/Articles/An_Interview_with_Merton_Miller.aspx.

6 “Where Nobel Economists Put Their Money,” accessed October 30, 2010, http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=9128160907104616152#.

7 Ibid.

8 “Arithmetic of Active Management,” Financial Analysts' Journal, 47, No. 1, January/February 1991, 7.

9 Ibid.

10 John C. Bogle, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), xiv.

11 David F. Swensen, Unconventional Success, a Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment (New York: Free Press, 2005), 217.

12 Robert D. Arnott, Andrew L. Berkin, and Jia Ye, “How Well Have Taxable Investors Been Served in the 1980s and 1990s?” The Journal of Portfolio Management, Summer 2000, Vol. 26, No.4, 86.

13 Larry Swedroe, The Quest For Alpha (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 13.

14 Larry Swedroe, The Quest For Alpha, 13–14.

15 David F. Swensen, Unconventional Success, a Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment, 217.

16 Ibid., 266.

17 Ibid.

18 John C. Bogle, Common Sense on Mutual Funds (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), 376.

19 Ibid., 384.

20 John C. Bogle, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing, 61.

21 John C. Bogle, Common Sense on Mutual Funds, 376.

22 Ibid.

23 Dilbert Comics, Reprinted with permission, Order Receipt #1591582.

24 John C. Bogle, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing, 90.

25 John C. Bogle, Don't Count On It! (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 382.

26 Burton Malkiel, The Random Walk Guide to Investing (New York: Norton, 2003), 130.

27 Ibid.

28 Bruce Kelly, “Raymond James Unit Gives Bonuses to Big Producers,” I nvestment News—The Leading Source for Financial Advisors, June 18, 2007.

29 Carole Gould, “Mutual Funds Report; A Seven-Year Lesson in Investing: Expect the Unexpected, and More,” The New York Times, July 9, 2000, accessed April 15, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2000/07/09/business/mutual-funds-report-seven-yearlesson-investing-expect-unexpected-more.html?.

30 Bert Whitehead, Why Smart People Do Stupid Things With Money (New York: Sterling Publishing, 2009), 205.

31 Ajay Khorana, Henri Servaes, and Peter Tufano, “Mutual Fund Fees Around the World,” The Review of Financial Studies 2008, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Oxford University Press), accessed April 15, 2011, http://faculty.london.edu/hservaes/rfs2009.pdf.

32 “The Greatest Investors: Peter Lynch,” Investopedia, accessed April 15, 2011, http://www.investopedia.com/university/greatest/peterlynch.asp.

34 John C. Bogle, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing, 47–48.

35 Andy Serwer, “The Greatest Money Manager of Our Time,” Fortune, November 15, 2006, accessed: April 15, 2011, http://money.cnn.com/2006/11/14/magazines/fortune/Bill_miller.fortune/index.htm.

36 Jason Zweig, “What's Luck Got to Do with It?” Money, July 18, 2007, accessed April 15, 2011, http://money.cnn.com/2007/07/17/pf/miller_interview_full.moneymag/.

37 Paul B. Farrell, “‘Laziest Portfolio’ 2004 Winner Ted Aronson Scores Repeat Win with 15 percent Returns,” CBS Marketwatch.com, January 11, 2005, accessed April 15, 2011, http://www.marketwatch.com/story/results-are-in-and-laziest-portfolio-winner-is.

38 Mel Lindauer, Michael LeBoeuf, and Taylor Larimore, The Bogleheads Guide to Investing, 118.