RULE 2

Use the Greatest Investment Ally You Have

So much of what schools teach in a traditional mathematics class is . . . hmm, let me word this diplomatically, not likely to affect our day-to-day lives. Sure, learning the formulas for quadratic equations (and their abstract family members) might jazz the odd engineering student. But let’s be honest. Few people get aroused by quadratic equations.

Perhaps I’m committing heresy in the eyes of the world’s math teachers, but I think quadratic equations (a polynomial equation of the second degree, if that clears things up) are about as useful to most people as ingrown toenails and just as painful for some. Having said that, buried in the dull pages of most school math books is something that’s actually useful: the magical premise of compound interest.

Warren Buffett applied it to become a billionaire. More important, you can apply it, too. I’ll show you how.

Buffett has long jockeyed with Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates for the title of “World’s Richest Man.” He lives like a typical millionaire (he doesn’t spend much on material things) and he mastered the secret of investing his money early. He bought his first stock when he was 11 years old, and the multibillionaire jokes that he started too late.1

Starting early is the greatest gift you can give yourself. If you start early and if you invest efficiently (in a manner that I’ll explain in this book) you can build a fortune over time, while spending just 60 minutes a year monitoring your investments.

Warren Buffett famously quips: “Preparation is everything. Noah did not start building the Ark when it was raining.”2

Most of us are aware of the Biblical story about Noah’s Ark. God told him to build an Ark and to collect a variety of animals, and eventually, when the rains came, they would sail off to a new beginning. Luckily for the animals, Noah started building that Ark right away. He didn’t procrastinate.

But let’s imagine Noah for a second. The guy probably had a similar nature to you and me, so even if God told him to keep the upcoming flood a secret, he might not have. After all, he was human, too. So I can imagine him wandering down to the local watering hole. After having a couple of forerunners to Budweiser beer, I can see him whispering to a friend: “Hey listen, God is saying that the rains are going to come and that I have to build an Ark and sail away once the land is flooded.” Some of his buddies (maybe even all of them) might have figured that Noah had eaten some kind of naturally grown narcotic. A crazy story, they would think.

Yet, someone must have believed him. As far-fetched as Noah’s flood story might have sounded to his buddies, it would have inspired at least one of his friends to build an Ark—or at least a decent-sized boat.

Despite the best of intentions, though, that person obviously never got around to it. Maybe he planned to build it when he acquired more money to pay for the materials. Maybe he wanted to be sure, waiting to see if the clouds grew dark and it started sprinkling. English naturalist Charles Darwin might call this guy’s procrastination “natural selection.” Needless to say, he wasn’t selected.

For the best odds of amassing wealth in the stock and bond markets, it’s best to start early.

Thankfully your friends—if they procrastinate—won’t meet the same fate as Noah’s friends. But your metaphorical ship will sail off into the distance while others scramble in the rain to assemble their own boats.

Starting early is more than just getting a head start. It’s about using magic. You can sail away slowly, and your friends can come after you with racing boats. But thanks to the force described by Albert Einstein (some say) as more powerful than splitting the atom, they aren’t likely to catch you.

In William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the protagonist says to his friend: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

Hamlet was referring to ghosts. Einstein was referring to the magic of compound interest.

Compound Interest—The World’s Most Powerful Financial Concept

Compound interest might sound like a complicated process. But it’s simple.

If $100 attracts 10 percent interest in one year, then we know that it gained $10, turning $100 into $110.

You would start the second year with $110, and if it increases 10 percent, it would gain $11, turning $110 into $121.

You will go into the third year with $121 in your pocket, and if it increases 10 percent, it would gain $12.10, turning $121 into $133.10.

It isn’t long before a snowball effect takes place. Have a look at what $100 invested at 10 percent annually can do.

$100 at 10 percent compounding interest a year turns into:

- $161.05 after 5 years

- $259.37 after 10 years

- $417.72 after 15 years

- $672.74 after 20 years

- $1,744.94 after 30 years

- $4,525.92 after 40 years

- $11,739.08 after 50 years

- $78,974.69 after 70 years

- $204,840.02 after 80 years

- $1,378,061.23 after 100 years

Some of the lengthier periods above might look dramatically unrealistic. But you don’t have to be an immortal creep to benefit. Someone who starts to invest at 19 (like I did) and who lives until age 90 (which I hope to!) will have money compounding in the markets for 71 years. They will spend some of it along the way, but they’ll always want to keep a portion of their money compounding in case they live to 100.

The Inspirational Realities of Starting Early

After paying off your high-interest loans (whether they are car loans or credit-card loans) you will be ready to put Buffett’s Noah Principle to work. The earlier you start, the better—so if you’re 18 years old, start now. If you’re 50 years old, and you haven’t begun, there’s no better time than the present. You’ll never be younger than you are right now.

The money that doesn’t go toward expensive cars, the latest tech gadgets, and credit-card payments (assuming you have paid off your credit debts) can compound dramatically in the stock market if you’re patient. And the longer your money is invested in the stock market, the lower the risk.

We know that stock markets can fluctuate dramatically. They can even move sideways for many years. But over the past 90 years, the US stock market has generated returns exceeding nine percent annually.3 This includes the crashes of 1929, 1973–1974, 1987, and 2008–2009. In Stocks for the Long Run, University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School finance professor Jeremy Siegel suggests a dominant historical market, such as the United States, isn’t the only source of impressive long-term returns. Despite the shrinking global importance of England, its stock market returns since 1926 have been very similar to that of the United States. Meanwhile, not even two devastating world wars for Germany have hurt its long-term stock market performance, which also rivals that of the United States.4

My suggestion isn’t going to be to choose one country’s stock market over another. Some stock markets will do better than others, but without mythical crystal balls we’re not going to know ahead of time. Instead, to ensure the best chances of success, owning an interest in all of the world’s stock markets is a good idea. And you can benefit most by investing right away. The younger you are when you start to invest, the better.

Grow Wealthier than Your Neighbor While Investing Less

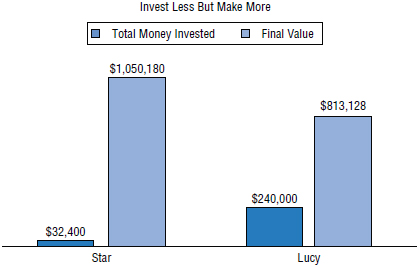

The question below showcases how powerful the “Noah Principle” of starting early really is.

- Would you rather invest $32,400 and turn it into $1,050,180? Or,

- Would you rather invest $240,000 and turn it into $813,128?

Sure it’s a dumb question. Anyone who can fog a mirror would choose A. But because most people haven’t had a strong financial education, the vast majority would be lucky to face scenario B—never mind scenario A.

If you know anyone who’s really young, they can benefit from your knowledge. They can feasibly turn $32,400 into more than a million dollars. But don’t weaken them by giving them money. Make them earn it. Here’s how it can be done.

The Bohemian Millionaire—The Best of Historical-Based Fiction

A five-year-old girl named Star is raised by her mother, Autumn, and brought up on a Bohemian island where the locals make their own clothes, where neither men nor women use razors to shave, and where no one tries to mask the aphrodisiac quality of good old-fashioned sweat.

Unfortunately, despite how appealing this might sound (especially at tightly congested town hall meetings), it isn’t paradise. Islanders and locals often throw empty aluminum beverage cans into ditches. Autumn convinces Star that collecting those cans and recycling them can help the environment and eventually make her a millionaire. Autumn takes Star to the local recycling depot where Star collects an average of $1.45 a day from refunded cans and bottles. Although a Bohemian at heart, Autumn’s no provincial bumpkin. She recognizes that if she persuades Star to earn $1.45 a day from can returns, she can invest the daily $1.45 to make Star a millionaire.

Putting it into the US stock market, Star earns an average of 9 percent a year (which is slightly less than what the stock market has averaged over the past 90 years). Autumn also understands what most parents do not: if she teaches Star to save, her daughter will become a financial powerhouse. But if she “gifts” Star money, rather than coaching her to earn it, then her daughter may become financially weak.

Fast-forward 20 years. Star is now 25 years old. She no longer collects cans from ditches. But her mother insists that Star sends her a $45 monthly check (roughly $1.45 per day). Autumn continues to invest Star’s money while Star hawks her handmade Dream Catchers at the local farmer’s market.

Living in New York City, Star’s best friend Lucy works as an investment banker. (I know you’re wondering how these two hooked up, but roll with it. It’s my story.) Living the “good life,” Lucy drives a BMW, dines at gourmet restaurants, and blows the rest of her significant income on clothing, theater shows, expensive shoes, and flashy jewelry.

At age 40, Lucy begins to save $800 a month. She gets on Star’s case, via e-mail, about Star’s limited $45-a-month contribution to her financial future.

Star doesn’t want to brag but she needs to set Lucy straight.

“Lucy,” she writes, “you’re the one in financial trouble, not me. It’s true that you’re investing far more money than I am, but you’ll need to invest more than $800 a month if you want as much as I’ll have when I retire.”

The e-mail puzzles Lucy, who assumes that Star must have ingested some very Bohemian mushrooms to write such cryptic nonsense.

Twenty-five years later, both women are 65 years old. They decide to rent a retirement home together in Lake Chapala, Mexico, where their money would go further.

“Well,” inquires Star, “Did you invest more than $800 a month like I suggested?”

“This is coming from someone who invested just $45 a month?” asks Lucy with surprise.

“But Lucy, you ignored the Noah principle, so despite investing far more money, you ended up with a lot less than I did because you started investing so much later.”

Both women achieved the same return in the stock market. Some years they gained money. Other years, they lost money. But overall, they each averaged a compound return of 9 percent per year.

Figure 2.1 shows that because Star started early, she was able to invest a total of $32,400 and turn it into more than $1 million. Lucy started later, invested nearly eight times more, but ended up with $237,052 less than Star.

Figure 2.1 Turning Less into More

I didn’t start investing until I was 19, so Star would have had the jump on me. But I started far earlier than most, so I have had more time to let the Noah Principle work its magic. I put money in US and international stock markets that, from 1990 to 2016, have averaged more than 9 percent per year. The money that I put in the market in 1990 had grown to 10 times its original value by 2016.

When I tell young parents about the power of compounding money, they often want to set money aside for their children’s future. “Setting aside” money for a child, however, is very different from encouraging a child to earn, save, and invest.

Giving money promotes weakness and dependence.

Teaching money lessons and cheerleading the struggle promotes strength, independence, and pride.

Gifting Money to Yourself

In 2005, I was having dinner with a couple of school teachers. We started to talk about saving money. They wanted to know how much they should save for their retirement. Unlike most public school teachers, who can look forward to pensions when they retire, these friends are in the same boat as me. As private school teachers, they’re responsible for their own retirement money.

I threw out a minimum dollar figure that I thought they should save each month. It was double what they were currently saving.

The woman (who I’ll call Julie) thought it was an attainable amount. Her husband (who I’ll call Tom) thought it was crazy. So I asked them to do a couple of things:

- Write down everything they spent money on for three months, including food costs, mortgage costs, gas for the car, and health insurance.

- At the end of those three months, figure out what it cost them to live each month.

The next time we had dinner together, they told me their results, which had given them both a jolt. Julie was surprised at how much she was spending on eating out, buying clothes, and purchasing small items such as Starbucks coffee.

Tom was surprised at how much he was spending on beers at the clubhouse when he went golfing with his buddies.

After three months, they began to change. Pulling receipts from their wallets and writing down their expenses each evening made them realize how much they were squandering. As Tom explained: “I knew that I had to write those purchases down at the end of the day, which acted as an accountability measurement. So I started spending less.”

Financially efficient households know what their costs are. By writing down expenses, two things occur. You get an idea of how much you spend in a month, providing an idea of how much you can invest. It also makes you accountable for your spending, which encourages most people to cut back.

The next step is to figure out exactly what you get paid in the average month.

When you subtract your average monthly expense costs from your income, you can get an idea of how much you can afford to invest. Don’t wait until the end of the month to invest that money; instead, make the transfer payment to your investment of choice on the day you get paid. Otherwise, you might not have enough left at the end of the month (after a few too many nights out) to follow through with your new financial plan. My wife made that mistake before we were married. She invested whatever amount she had left in her account at the end of the month or the end of the year. When she switched things around and automatically had money transferred from her savings account on the date she was paid, she ended up investing twice as much.

My friends Julie and Tom had the same realization. After a year, they had doubled the amount that they were investing. Two years later when the same conversation came up, I found they had tripled the amount they were originally putting away. Both said the same thing: “We didn’t know where that money was going each month. It doesn’t feel like we live any differently than we did three years ago, but the deposits in our investment account don’t lie. We’ve tripled our savings.”

My wife and I document every penny we spend with an expense tracking app on our iPhone. It’s easy. After coming out of a grocery store or restaurant, for example, we enter our costs right away. My wife rolls her eyes as I excitedly tell anyone within earshot, “This is the best thing ever!” Then she drags me outside before I embarrass her further.

By documenting what you spend, you’ll fall into a healthy spending pattern. It will allow you to invest much more money over time.

Here’s another useful tip. Over the years, your salary will most likely rise. If it increases by $1,000 in a given year, add at least half of it to your investment account, while putting the rest in a separate account for something special. That way, you’ll get rewarded twice for the salary increase.

When You Definitely Shouldn’t Invest

Before getting wrapped up in how much money you can save and invest, there’s one thing to consider. Are you paying interest on credit cards? If you are, then investing money doesn’t make sense. Most credit cards charge 18 to 24 percent in interest annually. Not paying them off in full at the end of the month means that your friendly card company (the one you’ll never leave home without) is sucking your money from an intravenous drip attached to your femoral artery. You don’t have to be a genius to realize that paying 18 percent interest on credit-card debt and investing money that you hope will provide returns of 8 to 10 percent makes as much sense as bathing fully clothed in a tub of Vaseline and then travelling home on the roof of a bus.

Paying off credit-card debt that’s charging 18 percent in interest is like making a tax-free 18-percent gain on your money. And there’s no way that your investments can guarantee a gain like that after tax. If any financial adviser, advertisement, or investment group of any kind promises a return of 18 percent annually, think of disgraced US financier Bernie Madoff and run. Nobody can guarantee those kinds of returns.

Well, nobody except the credit-card companies. They’re making 18 to 24 percent annually from you (if you carry a balance), not for you.

How and Why Stocks Rise in Value

You might be wondering how I averaged about 9.5 percent a year on the stock market for 25 years. There were certainly years when my money dropped in value, but there were years when I earned a lot more than 9.5 percent as well.

Where does the money come from? How is it created?

Imagine Willy Wonka (from Roald Dahl’s classic novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory). Willy started out with a little chocolate shop. Having big dreams, he wanted to make ice cream that didn’t melt, chewing gum that never lost its flavor, and chocolate that would make even the devil sell his soul.

But Willy didn’t have limitless money to grow his business. He needed to buy a larger building, hire more of those creepy little workers, and purchase machinery that would make chocolate faster than he ever could before.

So Willy hired someone to approach the New York Stock Exchange. Before Willy knew it, he had investors in his business. They bought parts of his business, also known as “shares” or “stock.” Willy was no longer the sole owner, but by selling part of his business to new shareholders, he was able to build a larger, more efficient factory with the shareholder proceeds. This increased the chocolate factory’s profits because he was able to make more treats at a faster rate.

Willy’s company was now “public,” meaning that the shareowners (should they choose to) could sell their stakes in Willy’s company to other willing buyers. When a publicly traded company has shares that trade on a stock market, the trading activity has a negligible effect on the business. So Willy, of course, was able to concentrate on what he did best: making chocolate. The shareholders didn’t bother him because generally, minority shareholders don’t have any influence in a company’s day-to-day operations.

Willy’s chocolate was amazing. Pleasing the shareholders, he began selling more and more chocolate. But they wanted more than a certificate from the New York Stock Exchange or their local brokerage firm to prove that they were partial owners of the chocolate factory. They wanted to share in the business profits that the factory generated. This made sense because shareholders in a company are technically owners.

So the board of directors (which was voted into their positions by the shareholders) decided to give the owners an annual percentage of the profits and everyone was happy. This is how it worked: Willy’s factory sold about $100,000 worth of chocolate and goodies each year. After paying taxes on the earnings, employee wages, and maintenance costs, Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory made an annual profit of $10,000, so the company’s board of directors decided to pay its shareholders $5,000 of that annual $10,000 profit and split it among the shareholders. This is known as a dividend.

The remaining $5,000 profit would be reinvested back into the business—so Willy could pay for bigger and better machinery, advertise his chocolate far and wide, and make chocolate even faster, generating higher profits.

Those reinvested profits made Willy’s business even more lucrative. As a result, the Chocolate Factory doubled its profits to $20,000 the following year, and it increased its dividend payout to shareholders.

This, of course, caused other potential investors to drool. They wanted to buy shares in the factory, too. Now there were more people wanting to buy shares than there were people who wanted to sell them. This created a demand for the shares, causing the share price on the New York Stock Exchange to rise. (If there are more buyers than sellers, the share price rises. If there are more sellers than buyers, the share price falls.)

Over time, the share price of Willy’s business fluctuated: sometimes climbing, sometimes falling, depending on investor sentiment. If news about the company was good, it increased public demand for the shares, pushing up the price. On other days, investors grew pessimistic, causing the share price to fall.

Willy’s factory continued to make more money over the years. And over the long term, when a company increases its profits, the stock price generally rises along with it.

Willy’s shareholders were able to make money in two different ways. They could realize a profit from dividends (cash payments given to shareholders usually four times each year) or they could wait until their stock had increased substantially in value on the stock market and choose to sell some or all of their shares.

Here’s how an investor could hypothetically make 10 percent a year from owning shares in Willy Wonka’s business.

Montgomery Burns had his eye on Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory shares, and he decided to buy $1,000 of the chocolate company’s stock at $10 a share. After one year, if the share price rose to $10.50, this would amount to a 5 percent increase in the share price ($10.50 is 5 percent higher than the $10 that Burns paid).

And if Burns was given a $50 dividend, we could say that he had earned an additional 5 percent because a $50 dividend is five percent of his initial $1,000 investment.

So if his shares gain 5 percent in value from the share-price increase and he makes an extra 5 percent from the dividend payment, then after one year Burns potentially would have made a 10 percent profit on his shares. Of course, only the 5 percent dividend payout would go into his pocket as a “realized” profit. The 5 percent “profit” from the price appreciation (as the stock rose in value) would only be realized if Burns sold his Willy Wonka shares.

Montgomery Burns, however, didn’t become the richest man in Springfield by buying and selling Willy Wonka shares when they fluctuated in price. Studies have shown that, on average, investors who buy shares and sell them again quickly don’t tend to make profits as high as investors who hold onto their shares over the long term.

Burns held onto those shares for many years. Sometimes the share price rose and sometimes it fell. But the company kept increasing its profits, so the share price increased over time. The annual dividends kept a smile on Montgomery Burns’ greedy little lips, as his profits from the rising stock price, coupled with dividends, earned him an average potential return of 10 percent a year.

However, Burns wasn’t rubbing his bony hands together as gleefully as you might expect because at the same time he bought Willy Wonka shares, he also bought shares in Homer’s donuts and Moe’s Tavern. Neither business worked out, and Burns lost money.

Driving him really crazy, however, was missing out on shares in the joke-store company, Bart’s Barf Gags. If Burns had bought shares in this business, he would be laughing—all the way to the bank. Share prices quadrupled in just four years.

In the following chapter, I’ll show you that one of the best ways to invest in the stock market is to own every stock in the market, rather than trying to follow the strategy of Burns and guess which stocks will rise. Though it sounds impossible to buy virtually every stock in a given market, it’s made easy by purchasing a single product that owns every stock within it.

Before getting to that, remember that you can invest half of what your neighbors invest over your lifetime and still end up with twice as much money—if you start early enough. For patient investors, the aggregate returns of the world’s stock markets have dished out fabulous profits.

For example, the US stock market averaged 10.16 percent annually from 1920 to 2016. There were periods where it grew faster than that, while it dropped back at other times. But that 10.16 percent average return has provided some impressive long-term profits.

Of course, the stock market doesn’t grow each and every year. Some years between 1920 and 2016, US stocks exceeded a growth rate of 10.16 percent. Other years, stocks fell. But patient investors get rewarded.

Here’s an example. Assume you had invested $1,600 in the US stock market at the beginning of 1978. If you had added $100 per month, come hell or high water, you would have practiced something called dollar-cost averaging. Instead of speculating whether it was a “good time” or “bad time” to invest, you would have put your money on autopilot. Here’s how that money would have grown in a tax-free account, if you had added $100 per month to the initial $1,600 investment between 1978 and August 2016 (the time of this writing).

Table 2.1 Dollar Cost Averaging with US Stocks Starting with $1,600 and Adding $100 Per Month

| Year Ending | Total Cost of Cumulative Investments | Total Value after Growth |

| 1978 | $1,600 | $1,699 |

| 1979 | $2,800 | $3,273 |

| 1980 | $4000 | $5,755 |

| 1981 | $5,200 | $6,630 |

| 1982 | $6,400 | $9,487 |

| 1983 | $7,600 | $12,783 |

| 1984 | $8,800 | $14,863 |

| 1985 | $10,000 | $20,905 |

| 1986 | $11,200 | $25,934 |

| 1987 | $12,400 | $28,221 |

| 1988 | $13,600 | $34,079 |

| 1989 | $14,800 | $46,126 |

| 1990 | $16,000 | $45,803 |

| 1991 | $17,200 | $61,009 |

| 1992 | $18,400 | $66,816 |

| 1993 | $19,600 | $74,687 |

| 1994 | $20,800 | $76,779 |

| 1995 | $22,000 | $106,944 |

| 1996 | $23,200 | $132,767 |

| 1997 | $24,400 | $178,217 |

| 1998 | $25,600 | $230,619 |

| 1999 | $26,800 | $280,564 |

| 2000 | $28,000 | $256,271 |

| 2001 | $29,200 | $226,622 |

| 2002 | $30,400 | $177,503 |

| 2003 | $31,600 | $229,523 |

| 2004 | $32,800 | $255,479 |

| 2005 | $34,000 | $268,932 |

| 2006 | $35,200 | $312,317 |

| 2007 | $36,400 | $330,350 |

| 2008 | $37,600 | $208,940 |

| 2009 | $38,800 | $265,756 |

| 2010 | $40,000 | $301,098 |

| 2011 | $41,200 | $302,298 |

| 2012 | $42,400 | $344,459 |

| 2013 | $43,600 | $403,514 |

| 2014 | $44,800 | $458,028 |

| 2015 | $46,000 | $463,754 |

| August 2016 | $46,800 | $498,904 |

Source: A Random Walk Down Wall Street (11th edition); Morningstar.com, using returns from the S&P 500.

Between 1978 and August 23, 2016, the investor would have added just $46,800. But the money would have grown to $498,904. To build such massive wealth, it’s best to start early. Let me show you how.