RULE 7

No, You Don’t Have to Invest on Your Own

The world is Internet-savvy. Millions of people have learned that actively managed mutual funds pad Wall Street’s pockets. Low-cost index funds, by comparison, give more to investors.

The public doesn’t need an Occupy Wall Street protest. Instead, they can vote with their wallets. Many run to Vanguard. It’s the world’s biggest provider of index funds. It’s also now bigger than any actively managed mutual fund company in the world.

Vanguard has a hippie-like backstory. John Bogle started the company in 1974. He set it up like a nonprofit firm. If you buy its index funds, you’re an owner of the firm. No private investors own a piece of the company pie. Unlike most banks (and many mutual fund companies), no public shares trade on the stock market.

Instead, Vanguard was created for the people. It was capitalism born in a commune. Until recently, however, most people had to go solo if they wanted a portfolio of index funds. They waded through Vanguard’s offerings of index funds without any guidance. Or they built their own portfolios with ETFs (hip little cousins of the traditional index fund).

These two options are still the cheapest way to go. They take less than an hour a year. You never have to follow stock market news or forecasts. Your results would also dust those of most professional investors.

But for some investors, that feels like running naked. Many prefer the clothing and the guidance of a financial advisory firm. Your grandparents couldn’t have done this—without getting handcuffed and stuffed into actively managed mutual funds. Your parents couldn’t have either. But times have changed.

Enter robo-advisers. No, they aren’t run by robots. That’s a media-created name that rings well with science fiction. I prefer to call them intelligent investment firms. Most are Internet-based. These firms have said, “People are getting smarter. Let’s offer something better!”

Such firms are now present in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, and Asia. They build and manage portfolios of index funds, charging low fees to do so. Costs and services, however, vary. Some provide comprehensive financial planning (investments, estate planning, tax advice, etc.). Others just invest your money.

Traditional investment firms usually lie in bed with actively managed funds. These firms are like horse-drawn buggies. Intelligent investment firms (robo-advisers, if you must) are hybrids or Teslas. No matter how you slice it, they perform much better and they cost a lot less.

But why pay somebody, even a small amount, when you could invest on your own?

Are You Wired Like a Buddha?

Could you sit cross-legged on a stone . . . with a little smile on your face . . . in a five-hour rainstorm? If not, congratulations, you’re normal. But investors who are capable of building and maintaining a portfolio of index funds might require something special. Don’t feel misled. The process is simple. It takes less than one hour a year.

But it’s easier said than done. Market rainstorms occur when nobody expects them. Stormy headlines will try to push you from that rock.

For years, I’ve been giving seminars to DIY investors. My lessons are simple. For Americans (as an example), I recommended a US stock index, an international stock index, and a US bond market index. Investors should add money every month. Ignore investment forecasts. Rebalance once a year to maintain a constant allocation.

In other words, if the portfolio were split equally in thirds between the three index funds at the beginning of the year, investors would need to make sure that it was adjusted, at year-end, so it was equally split in thirds 12 months later.

It’s as simple as lying in a hammock. But most people get itchy butts. They add fresh money to the index that’s “doing well.” They often ignore the index that may be dropping in value. This damages long-term results.

It gets even worse if investors listen (and act on) financial pornography in the news. That’s what I call financial forecasts. Such forecasts are almost always wrong. But they influence plenty of people.

Here’s an example.

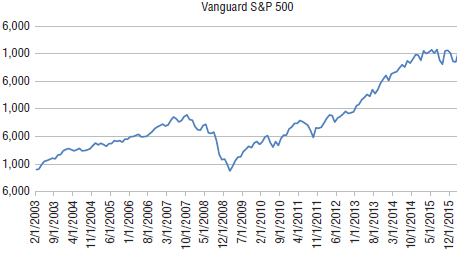

Vanguard’s S&P 500 index averaged a compound annual return of 6.89 percent per year during the 10-year period ending March 31, 2016. That included the massive stock market crash of 2008–2009, when US stocks dropped nearly 40 percent. But the average investor in the S&P 500 did the funky chicken. The typical investor in the S&P 500 averaged a compound annual return of just 4.52 percent during that same time period.1

How Does the Average Index Investor Underperform the Index?

In Figure 7.1, you’ll see a 13-year performance chart of the S&P 500. Note how the index rose, without much interruption, between 2003 and 2007. Each year, as the index rose higher, more investors piled in. They were happy. They were confident.

Figure 7.1 S&P 500, March 31, 2003-March 31, 2016

Source: © The Vanguard Group, Inc., used with permission

By 2008, stocks began to fall, as shown in Figure 7.1. News reports said that stocks would fall further. Buddhas didn’t care. But many would-be meditators ditched their robes and sold. In 2011, after the index had a couple of good years, many investors on the sidelines started to buy once again.

This is like buying more rice when prices are high, and buying less (or none at all) when it’s on sale. By doing so, people pay above average prices over time.

That tumultuous decade saw Vanguard’s S&P 500 gain an average of 6.89 percent per year for the period ending March 31, 2016. But according to Morningstar, the typical investor in that fund averaged a compound return of just 4.52 percent per year. They preferred to buy on highs. They added less (or sold!) on lows.

The free online website Portfoliovisualizer.com shows how much a disciplined investor would have earned. Anyone adding a fixed monthly sum to the S&P 500 index between March 2003 and March 2016 would have averaged a compound annual return of 8.96 percent per year.

By purchasing a fixed amount every month, the investor would have bought more units when the fund prices were lower and fewer units when the fund prices were higher. The fund’s posted return, during this time period, was 6.89 percent per year. But an investor who added regular sums each month would have paid a lower-than-average price for those fund units over time. That’s how the investor would have averaged a compound annual return of 8.96 percent.

Building a portfolio of index funds on your own is simple. But if you can’t sit on a rock (or in a hammock) and ignore the world’s noise, consider hiring an intelligent investment firm. Like Buddhas, such firms would do the rock sitting for you. They would also rebalance your portfolio once a year.

Intelligent Investing for Americans

There’s a growing number of intelligent investment firms now available to Americans. Such companies use low-cost index funds or ETFs. Best of all, they can also prevent investors from sabotaging their accounts. Are their extra fees worth it? Most of the time, yes.

Vanguard

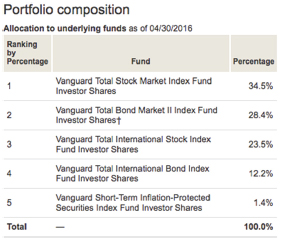

My wife is a financial schizophrenic. We spend more than $5,000 a year on massages. She thinks nothing of it. But she would slap my hand if I picked up an extra basket of organic blueberries. She also draws the line on investment costs. She owns a Vanguard Target Retirement 2020 (VTWNX) fund, shown in Figure 7.2. Its total fees are just 0.14 percent per year.

Figure 7.2 What’s Under the Hood?: Vanguard Target Retirement 2020 Fund

Source: Vanguard Research Center, Vanguard.com

This product doesn’t fall under the media’s robo-advisory label. But it should. It’s a low-cost, hassle-free way to have a complete portfolio of index funds that’s wrapped into a single product. Her fund allocations are shown in Figure 7.2

It’s a balanced fund that contains a US stock index, two US bond indexes, an international stock index, and an international bond index. In other words, she has exposure to the world with just one fund. Vanguard automatically rebalances each fund’s holdings once a year.

Studies show that nobody can predict, with any degree of accuracy, which country’s stock market is going to do well in any given year. That’s why smart investors don’t speculate. Instead, as with investors in Vanguard’s Target Retirement Funds, they own a bit of everything. They also maintain a fairly constant allocation without trying to forecast anything.

Data-crunching firm CXO Advisory proves that trying to forecast the stock market is like panning for gold with chopsticks. Between 2005 and 2012, the firm collected 6,584 forecasts by 68 experts. When predicting the direction of the stock market, the experts were right just 46.9 percent of the time.2 Coin flippers would have beaten them.

Vanguard’s Target Retirement Funds offer the cheapest all-in-one portfolios in the world. If you choose to invest in one, you don’t need anything else. Once a year, Vanguard rebalances the portfolio’s holdings. No, they don’t shuffle the portfolio deck based on which of its index fund holdings are expected to soar in the year ahead. Speculation doesn’t work. So Vanguard doesn’t bother.

Instead, the firm rebalances the holdings once a year to reflect a constant allocation.

Each of Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds has a slightly different name, with a year at the end of it. For example, investors who plan to retire in the year 2025 might choose Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2025 fund. Those who hope to retire in 2035 might choose Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2035 fund.

Every couple of years, each respective fund reduces its exposure to stocks, increasing its exposure to bonds. As people get closer to retirement, most people shouldn’t have a stock-heavy portfolio. Stocks perform better than bonds over the long haul. But they are riskier and short term. Many retirees (and those getting close to retirement) prefer a portfolio that’s more stable.

There are two examples in Figure 7.3

Figure 7.3 Vanguard Target Retirement 2010 Fund vs. Vanguard Target Retirement 2045 Fund: 5-year Performance Ending May 23, 2016

Source: © The Vanguard Group, Inc., used with permission

Figure 7.3 tracks the performance of two such funds over the five-year period ending May 23, 2016. They include Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2010 fund and Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2045 fund.

Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2045 fund was the better performer of the two. It gained a total of 42.65 percent over five years. By comparison, Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2010 fund gained 29.55 percent.

But Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2045 fund took on higher risk. It contains mostly stock market index funds, with far lower exposure to bond market indexes. Over time, stocks beat bonds. But bonds are more stable. Young investors, for example, can afford to take higher risk for the possibility of higher future returns. When stock markets fall, they have more time to recover.

Older investors usually prefer stability. After all, many are living on the proceeds of their retirement accounts. For this reason, most retirees would prefer a fund like Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2010 fund. It’s much more stable.

As of this writing, Vanguard offers 11 Target Retirement Funds. I’ve listed them in Table 7.1. You can see their stock/bond allocations and their expense ratios.

Table 7.1 Vanguard’s Target Retirement Funds

| Fund | Stock Allocation | Bond Allocation | Expense Ratio |

| Vanguard Target Retirement Income | 30% | 70% | 0.14% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2010 | 34% | 66% | 0.14% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2015 | 50% | 50% | 0.14% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2020 | 60% | 40% | 0.14% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2025 | 65% | 35% | 0.15% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2030 | 75% | 25% | 0.15% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2035 | 80% | 20% | 0.15% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2040 | 90% | 10% | 0.16% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2045 | 90% | 10% | 0.16% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2050 | 90% | 10% | 0.16% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2060 | 90% | 10% | 0.16% |

Source: Vanguard.com

I’m a huge fan of these funds. We own Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2020 fund in my wife’s account.

If a deranged mutual fund salesperson decided to toss me off a bridge, my wife wouldn’t have to worry about her money. She would rather dine on dirt than manage it herself. Fortunately, Vanguard does it for her.

The average DIY investor could build a portfolio of individual index funds or ETFs at a slightly lower cost. But my wife’s portfolio will beat most of them. Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds keep investors calm. That might sound like a strange claim. But let me explain.

Most investors in these funds invest the same amount of money every month (dollar-cost averaging). Many do it through their employers’ 401(k)s. Many never look at their portfolios or follow the markets. Not doing so gives them strong odds of earning good returns.

I looked at Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds with 10-year track records. Morningstar reveals how each fund performed compared to how its average investor did.3

This 10-year period included the stock market crash of 2008–2009. This was when investors freaked. Between 2005 and 2015, Vanguard’s S&P 500 Index averaged 8 percent per year. But the typical investor in the S&P 500 averaged just 6.37 percent per year during the same time period. Once again, fear, greed, and speculation pulled them by the gonads. They ceased to buy when they should have been buying. Sometimes they even sold.

Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds had the opposite effect. Most of its investors kept adding money, every single month. This allowed them to buy more units when prices were low and fewer units when prices rose. As a result, they paid less than the average price.

That’s how Vanguard’s Target Retirement investors outperformed their indexes. At the end of April 2015, I used Morningstar.com to see how they did. Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2035 fund averaged 7.04 percent for the 10 years ending April 30, 2015. But the typical investor in that same fund averaged a return of 8.65 percent per year. Remember, this included the market crash of 2008–2009.

Such was the case with all of Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds. Their investors played cool. They weren’t as worried about picking the wrong funds or rebalancing at the wrong time. As a result, their money outperformed the reported gains of their funds, as shown in Table 7.2

Table 7.2 Vanguard’s Target Retirement Investors Outperformed Their Funds, April 30, 2005 to April 30, 2015

| Fund | 10-year Annual Fund Return | 10-year Annual Investors’ Return |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2015 | 6.18% | 6.64% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2025 | 6.58% | 7.70% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2035 | 7.04% | 8.65% |

| Vanguard Target Retirement 2045 | 7.39% | 9.32% |

Source: Morningstar.com; All Vanguard Target Retirement funds with 10-year track records

Vanguard’s Full-Service Financial Advisers

Despite owning Vanguard’s Target Retirement Fund, my wife doesn’t seek advice from Vanguard. She doesn’t have a full-service adviser.

Full-service financial advisers deal with more than just investments. How much should you be saving? What kinds of investment accounts should you open to cover your children’s college costs? How should you deal with estate planning? How could you legally reduce your tax bite? They help with everything.

Done right, it’s a time-consuming process. That’s why most of the better financial advisers won’t take clients with accounts valued below $100,000.

Vanguard is changing that. Vanguard charges just 0.3 percent of a portfolio’s value each year for full-service financial planning. That’s just $300 on a $100,000 portfolio. A minimum of $50,000 is required for investors to qualify for this service. It’s available to all American residents. My apologies to the intrepid expats who live overseas. Vanguard (as with many US-based firms) doesn’t want you in their sandbox.

If you live in the United States, you might be tempted to race to your local Vanguard office. But you won’t find one. To keep costs down, they don’t have brick-and-mortar offices for retail investors. The new wave of low-cost firms is all online. Without multiple buildings to lease or buy, maintain, and power, such firms can save a lot of money. They pass the savings down to you.

I’ve listed a few intelligent investment firms below. Which is the best? That depends on what you’re looking for. Some investors may want to start their journey with a financial advisory firm. But if they develop Buddha-like discipline, they might then choose to branch out on their own. Such investors might prefer Vanguard’s advisory service or a boutique operation like RW Investment Strategies.

Is This the World’s Strangest Financial Adviser?

RW Investment Strategies is run by Robert Wasilewski. If I had to vote for the world’s strangest financial adviser, he would get my pick. Why? His goal is to ultimately fire himself. Most of the time he does.

He doesn’t believe you need to be a Buddha to build and maintain a portfolio of index funds or ETFs. He thinks almost anyone can do it—with the right initial guidance. “I charge 0.4 percent to manage assets less than $1 million,” says Wasilewski, “and 0.3 percent for assets above that. There’s an additional $150 quarterly charge for accounts I manage. I offer three services: hourly consulting at $150 an hour, investment management, and investment management with the goal of the client taking over investment management after three months or six months.”4

Of course, some of his clients want him to manage their money forever. “They’re sometimes too busy to do it themselves,” he says, “or they’re math-o-phobic.”

Investment Coaches Offer Guidance

PlanVision’s Mark Zoril offers something similar. He guides investors to open low-cost brokerage accounts with a firm like Vanguard or Schwab. He then guides the investor in the portfolio’s decision-making. PlanVision charges just $96 a year. As is the case with RW Investment Strategies, I hear great feedback from PlanVision’s clients.5

Investment Firms That Do The Lifting

Other investors might prefer a firm like AssetBuilder. Its co-founder, Scott Burns, is the man who created and popularized the DIY strategy called the Couch Potato portfolio in 1991. Back-tested studies prior to 1991 revealed that a combination of stock and bond indexes, rebalanced once a year, would trounce most investment professionals.

After 1991, the Couch Potato strategy continued to embarrass professional advisers everywhere. Many investors wanted to try it. But they struggled. They feared investing without an adviser. So in 2006, Scott Burns and Kennon Grose created AssetBuilder. They built a series of couch-potato-like portfolios using a different kind of index, offered by the firm Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA).

DFA’s index funds can only be purchased through a specific type of advisory firm. The firm’s advisers must attend a two-day educational conference, at their own cost, in Austin, Texas, or Santa Monica, California. Yet DFA, unlike most index fund companies, doesn’t try to equal market returns. They aim to beat them by tilting their emphasis toward small-cap (small company stocks) and value companies (stocks that are cheap, relative to their business earnings).

Sonny Wadera, a Canadian financial adviser with Kelson Financial Services Firm explains it well.

“Think of water getting poured into an ice tray,” he says. “The tray represents the entire market of stocks, but DFA tilts the tray slightly to one side, increasing the weightings of small-cap and value stocks.”6 Historically such stocks have outperformed the market.

Will they keep winning? Nobody knows for sure. But one thing is certain: DFA’s index funds are cheaper than actively managed funds. That’s why, like ordinary index funds, they’ll trounce most actively managed funds over an investment lifetime.

Firms like Betterment, Rebalance IRA, SigFig, and Wealthfront (see Table 7.3) are a lot like AssetBuilder. Investors determine their risk profile with a company representative. Investors send their money. The company then builds and manages a portfolio of index funds or ETFs.

Table 7.3 Intelligent Investment Firms That Build Portfolios of Index Funds

| Firm | Minimum Account Size | Annual Account Charges* | Rebalance and Manage Investments | Full-Service Financial Planning Included | Can Expatriates Open Accounts? |

| AssetBuilder** | $50,000 | 0.24% to 0.45% | Yes | No | Yes (depending on country of residence) |

| Betterment | None | 0.15% to 0.35% | Yes | No | No |

| PlanVision | $0 | $96 a year | Yes | No | Yes |

| Rebalance IRA | None | 0.50% Minimum $500 per year; $250 start-up fee | Yes | No | No |

| RW Investment Strategies | None | 0.30% to 0.40% | Yes | No | Yes |

| SigFig | $2,000 | 0.25% | Yes | No | No |

| Vanguard | $50,000 | 0.30% | Yes | Yes | No |

| Wealthfront | $5,000 | 0.25% | Yes | No | No |

*With account charge ranges, larger accounts are charged less, as a percentage of assets.

**Full Disclosure. I write for AssetBuilder.com.

Intelligent Investing Firms for Canadians

Canadians are nice. Sure, there’s a cross-section of folks who drop the F bomb and the gloves when they get knocked against the boards. But most Canadians are known for their politeness. They say please, thank you, and sorry a lot.

Kindness is a strength. But Canada’s financial institutions take advantage. They charge Himalayan costs for their actively managed funds. Canada’s banks also have their own brands of index funds.

I don’t recommend that you buy the index funds offered by Canada’s banks (with the exception of TD’s e-Series indexes). But I bring them up to show you something about Canada’s banking culture. I want to explain why you shouldn’t walk into a Canadian bank and say, “Please build me a portfolio of your index funds.”

First of all, most bank-sold index funds aren’t cheap—as far as index funds go. True, they cost less than half of what the banks charge for their actively managed products. They also make the banks’ active funds look silly. For the Globe and Mail I wrote a series of articles comparing the banks actively managed mutual funds to their index funds. In each case, overall, the indexes won.

But the smiling folks at the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, the Royal Bank of Canada, or the Bank of Montreal aren’t your buddies.

The banks make much more money when they sell actively managed funds. Millions of investors get the shaft.

In 2016, I joined a Facebook page for owners of a condominium complex in Victoria, British Columbia. I posted the following message:

I’m looking for four people who will each walk into a different Canadian bank. I’ll pay you each $50. I would like you to book an appointment with a financial adviser and ask him or her if they could build you a portfolio of index funds.

Four Generation Xers jumped at the offer. Within a week, I had received details of visits to the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC), Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), Toronto Dominion Bank (TD), and the Bank of Montreal (BMO).

Some took a pencil and paper to write notes. Others recorded the conversations with their iPhones. None of the advisers wanted to build a low-cost portfolio with the bank’s index funds. They offered actively managed funds instead. On average, the funds that they offered cost 2.2 percent per year—more than double the cost of the bank’s index funds. The advisers’ lack of knowledge and disclosure shocked Tim Godfrey.

Tim, an economics and finance graduate of Dalhousie University, was my first keen reporter. A few years previous, he had worked at the Australian Treasury. “I was advising the government on the regulation of financial advice,” he said. “We were determining how investment fees should be disclosed to clients.”

I had hit the jackpot. Without knowing it, I had recruited Sidney Crosby for a beer league game. “The adviser said that index funds are riskier than actively managed funds,” said Tim. “That surprised me. After all, risk has nothing to do with whether a fund is active or passive [indexed]. Portfolio allocation is what determines risk.”7

Tim is right. Take two portfolios. One is comprised of actively managed funds. It’s split four ways between Canadian government bonds, Canadian stocks, US stocks, and international stocks. In other words, 25 percent of the portfolio is invested in Canadian government bonds and 75 percent is invested in global stocks.

Compare that to a portfolio of index funds. If it contains 40 percent in Canadian government bonds, with the remaining 60 percent invested in global stocks, such a portfolio would have a far lower risk profile than an actively managed portfolio with 25 percent in bonds.

Deborah Bricks, a 36-year-old events planner, was my second reporter who headed to the bank. She chose the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC). “I asked if she [the adviser] could build me a portfolio of index funds,” Deborah says. “But she dismissed that idea pretty quickly.”

Deborah already owned RBC’s Select Balanced fund in her RRSP portfolio. It’s an actively managed fund that charges 1.94 percent per year. The adviser suggested that she keep it.

“An index fund just holds a single market,” said the adviser. “If you did buy an index fund, you would have to figure out which one to buy. Do you want a US index fund or a Canadian one? RBC’s Select Balanced fund is more diversified. It’s better because it’s actively managed.”8

Deborah spoke to an adviser who didn’t have a clue. The adviser didn’t seem to understand that she could build a diversified portfolio with the bank’s index funds.

Marina McKercher is a 30-year-old dental hygienist who walked into the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC). A great saver, she had $20,000 sitting in cash, ready to invest. The adviser immediately showed her CIBC’s Balanced Portfolio fund and CIBC’s Managed Income Portfolio fund. “He had data sheets on each of these two funds already printed out,” she says. The management expense ratios for the funds were 2.25 percent and 1.8 percent per year, respectively.

The bank’s index funds charged expense ratio fees that were less than half those amounts. Marina asked about the bank’s index funds instead. “The higher fee balanced funds are worth the extra costs,” said the adviser, “because the money is managed. The index funds would just sit there, not doing much of anything.”9

Dan Bortolotti, an Associate Portfolio Manager with PWL Capital says, “I’m not surprised many advisers have no clue about how to properly build a portfolio of index funds or ETFs. The way advisers are educated and trained presumes that their job is to beat the market by analyzing stocks and picking winning funds. The idea that an adviser might add value in other ways is foreign to them.”10

So far, there hasn’t been a revolution. Nobody has stormed Canada’s banks or mutual fund companies, armed with a hockey stick, demanding that they change.

That’s good. There’s no need to break noses. Evolution, instead of revolution, is a lot more Canadian. Canada’s Intelligent Investment firms give a nod to Darwin.

Would You Like a Tasty Tangerine?

In 2008, online banking firm Tangerine (formerly ING Direct) offered something sweet to the Canadian public: diversified portfolios of index funds wrapped up into single products. They cost just 1.07 percent per year. That isn’t cheap, by DIY standards. But it’s a great deal for investors who want a diversified portfolio of indexes. Unlike DIY investors, those with Tangerine don’t have to rebalance their portfolios. Tangerine does it for them.

That appeals to Katie Dixon. The 19-year-old from Kamloops, British Columbia, is far ahead of her time. “My high school offered the opportunity for some students to finish their graduation credits early,” she says. “Instead of attending high school for my senior year, I finished my high school graduation credits one year early [by grade 11] and enrolled in a six-month Health Care Assistant program.”

Katie graduated from the six-month program three months before most of her other friends finished their final year of high school. “The demand for care aides is high,” she says. “So I got a great job right away.” Katie will eventually study to become a nurse. Until then, she adds, “My work as a care aide pays a lot better than a typical summer job.”

When Katie was 18, she started to track her daily expenses with an app on her iPhone. “Keeping track of what I spent helped me to free up some money,” she says. That’s when she decided to commit to investing.

“I opened a high-interest savings account with Tangerine. I added $150 a month. It comes automatically out of my savings account. When I turned 19, I was eligible to open a TFSA account. I switched the accumulated cash over to Tangerine’s Equity Growth portfolio. Every month, I keep adding money to it.”11

Like I said, she’s way ahead of her time.

Tangerine is perfect for Canadians who are just starting out, want to invest small sums regularly, and would prefer to have a company build and rebalance a portfolio of index funds for them.

Katie’s portfolio is geared for growth. It contains a Canadian stock index, a US stock index, and an international stock index. Once a year, Tangerine rebalances the fund’s holdings.

Each of Tangerine’s three other funds would work well for investors with different time horizons and tolerances for risk. You can see them in Table 7.4

Table 7.4 Tangerine’s Index Fund Portfolios

| Fund | Best Suited For | Canadian Bonds | Canadian Stocks | US Stocks | International Stocks |

| Tangerine Balanced Income | Very conservative investors | 70% | 10% | 10% | 10% |

| Tangerine Balanced | Moderately conservative investors | 40% | 20% | 20% | 20% |

| Tangerine Balanced Growth | Investors looking for high growth with some stability | 25% | 25% | 25% | 25% |

| Tangerine Equity Growth | Young or aggressive investors | 0% | 50% | 25% | 25% |

Source: Tangerine.ca.

WealthBar

WealthBar offers five portfolio options for Canadian investors. They help clients determine their risk tolerance before they select a ready-made, diversified portfolio of ETFs. WealthBar does all the lifting. They offer full financial planning for those whose financial circumstances aren’t too complicated. They also build and rebalance client portfolios. All investors need to do is add money to their accounts.

The firm charges between 0.35 percent and 0.60 percent per year, depending on each account’s size. That’s WealthBar’s take. Investors pay a further 0.20 percent (approximately) to the separate ETF provider. Investors with accounts valued below $150,000 pay total fees of about 0.80 percent per year. Investors with account sizes between $150,000 and $500,000 pay 0.60 percent in total fees. Those with more than $500,000 pay just 0.40 percent.

To get started, new clients create a login password at wealthbar.com. As soon as they do so, a message appears.

Hi Andrew, I’m David, a financial adviser at WealthBar. I’m here if you have any questions about investing with WealthBar.

I’m generally available to chat between 9am-5pm PST M-F. You can schedule a call to discuss anything you like or contact me online through your WealthBar dashboard.

David, the financial adviser, isn’t WealthBar’s Siri. He’s a real person. Neville Joanes is WealthBar’s Portfolio Manager and Chief Compliance Officer. As he explains, “Everyone who logs in to WealthBar gets assigned a financial adviser.”12

The advisers look at each client’s long-term financial needs, based on their goals, savings rates, investment time horizons, insurance needs, as well as different tax-deferred account opportunities.

Investors can request a plan to be reviewed at any time, either online, or over the phone. Before doing so, investors fill in some easy-to-follow online questionnaires. They ask for information such as current savings rates, investment assets, types of accounts owned (if any), risk tolerances, and salary. Based on client-entered responses, they show a model of a suitable portfolio. Investors with questions can speak to an adviser.

WealthBar isn’t the only low-cost Intelligent Investing firm in Canada. I’ve listed others in Table 7.5. Each will build and maintain a portfolio of index funds. In each case, the firm will also rebalance the holdings at least once a year. That’s an important element that helps to reduce risk.

Table 7.5 Intelligent Investment Firms in Canada Build Portfolios of Index Funds

| Intelligent Investment Firm | Rebalances Index Holdings | Portfolios May Be Rebalanced Based on Market Forecasts* | Minimum Account Size | Annual Fees for a $5,000 Account** | Annual Fees for a $50,000 Account** | Annual Fees for a $200,000 Account** |

| BMO SmartFolio | Yes | Yes* | $5,000 | $74 = 1.5% | $487 = 0.97% | $1,850 = 0.92% |

| NestWealth | Yes | No | None (but fees are ridiculously high on small accounts) | $347 = 6.9% | $415 = 0.83% | $1,360 = 0.68% |

| Questrade Portfolio IQ | Yes | Yes* | $2,000 (but fees are ridiculously high on small accounts) | $131 = 2.6% | $545 = 1.1% | $1,980 = 0.99% |

| WealthBar | Yes | No | $5,000 | $12 = 0.25%*** | $430 = 0.86% | $1,710 = 0.85% |

| WealthSimple | Yes | No | None | $12 = 0.25%*** | $353 = 0.71% | $1,472 = 0.74% |

*Be skeptical of market forecasts.

**Annual fees include costs charged by the investment firm, plus the expense ratio costs of the index funds (ETFs).

***WealthBar and WealthSimple don’t charge fees for accounts valued below $5,000. Investors would just pay the expense ratios fees of the index funds (ETFs).

Some of the firms, however, adjust their portfolios based on market forecasts. That might sound sophisticated in a marketing brochure. But most market forecasts tend to be wrong. Statistically, firms that don’t adjust a portfolio’s position, based on forecasts, should perform better over an investment lifetime.

Intelligent Investing Firms for British Investors

Vanguard UK’s Target Retirement Funds

In 2015, Vanguard UK introduced its Target Retirement Funds. These are complete portfolios of indexes, wrapped up into single funds. They represent diversified baskets of UK and global stock and bond index funds. In other words, if you buy one of these, it’s all you really need.

Each fund has a designated date in the name. For example, investors who wish to retire in 2020 could buy Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2020 fund. Those who wish to retire in 2050 could buy Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2050 fund. There’s no obligation to hold these funds for any given period of time. Unlike many UK-based fund companies, Vanguard doesn’t charge penalties if investors choose to sell the fund after their initial purchase.

How Does Each Target Fund Differ?

Each target retirement fund has the same components. But the short-term risk and growth potentials differ. For example, in Table 7.6, you can see that investors who choose Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2050 fund would have higher stock allocations than investors in Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2020 fund. Younger investors can usually afford to take higher risks. When stocks fall, they have more time to wait for stocks to recover.

Table 7.6 Longer Time Horizons Warrant Higher Stock Allocations

| Fund | % In Bonds | % In Stocks |

| Target Retirement 2020 Fund | 41.3% | 58.7% |

| Target Retirement 2050 Fund | 19.9% | 81.1% |

Source: Vanguard UK, as of June 16, 2016

Conservative young investors, of course, could still buy Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2020 fund. Adventurous older investors could do likewise with Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2050 fund. Neither of the funds “expire” on any given date. Investors can remain invested long after the date in each respective fund’s name.

There’s another reason I like these funds. Vanguard rebalances the indexes in each of their target retirement funds once a year. Some investors might ask, “Why would I bother having Vanguard rebalance a portfolio of index funds for me? I could build and manage a portfolio of index funds on my own. It would also cost me less.”

These Target Retirement funds cost 0.24 percent per year. A DIY portfolio of Vanguard’s indexes or ETFs would cost slightly less.

But investors who build their own portfolios don’t usually perform as well. Morningstar’s studies report that DIY index fund investors usually underperform their funds because they often purchase high, sell low, and speculate on market news. Investors, who let Vanguard do the rebalancing, usually perform better (see Table 7.2 and the explanation that precedes it).

Annual rebalancing reduces risk. It can also boost returns.

What’s more, Vanguard increases each Target Retirement fund’s bond allocation over time. As investors get closer to their retirement dates, the funds become more conservative.

I’ve listed Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds in Table 7.7. Their annual expense ratios include all rebalancing. Vanguard also has a habit of reducing its fund expenses over time. By the time you read this, fees could be even lower.

Table 7.7 Vanguard’s (UK) Target Retirement Funds

| Fund | Annual Expense Ratio |

| Target Retirement 2015 Fund | 0.24% |

| Target Retirement 2020 Fund | 0.24% |

| Target Retirement 2025 Fund | 0.24% |

| Target Retirement 2030 Fund | 0.24% |

| Target Retirement 2035 Fund | 0.24% |

| Target Retirement 2040 Fund | 0.24% |

| Target Retirement 2045 Fund | 0.24% |

| Target Retirement 2050 Fund | 0.24% |

Source: Vanguard UK

What’s the Only Problem with These Funds?

In the United States, Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds require a minimum $3,000 initial investment. But if you want to buy one of these funds from Vanguard UK, you’ll need a lot more money than that. The initial investment for a direct purchase through Vanguard is an eye-watering £100,000.

This doesn’t mean that I’ve sent you down a rabbit hole. If you buy a Vanguard Retirement fund through a participating broker, you need far less money. Such intermediaries (or financial advisory firms) charge fees for you to buy these products. But it’s still a lot smarter than buying actively managed funds.

Vanguard UK lists its participating brokers on its website. But be careful. Some of the firms charge a percentage of the investors’ assets. Over time, this can be expensive. If a brokerage firm charges 0.45 percent and Vanguard’s expense ratio is 0.24 percent, investors would pay 0.69 percent per year for a Vanguard Target Retirement Fund. On a £50,000 account, that would be £345 a year. On a £100,000 account, it would cost £690.

Instead, find a financial services company that charges a flat annual fee.

Not Interested in a Target Retirement Fund?

Many Intelligent Investment Firms are popping up in the UK. But few of them use index funds exclusively or offer services to retail investors. Nutmeg, however, is one firm that does. Its costs are high, compared to their Canadian and US counterparts. But Nutmeg offers one of the best values in Britain. As competition heats up, costs will likely lower.

Table 7.8 shows how much Nutmeg’s investors would pay in fees to have a portfolio of index funds built and managed for them.

Table 7.8 Nutmeg’s Annual Fees, Based on Account Sizes

| Account Size | Annual Account Management Fee | Estimated Expense Ratio Charges for Index Funds | Total Annual Costs, Including Management and Fund Expense Ratios |

| Below £25,000 | 0.95% | 0.19% | 1.11% |

| £25,000 to £100,000 | 0.75% | 0.19% | 0.94% |

| £100,000 to £500,000 | 0.50% | 0.19% | 0.69% |

| £500,000+ | 0.30% | 0.19% | 0.49% |

Source: Nutmeg.com13

Intelligent Investing Firms for Australians

Ask an Australian on the street this question: What has performed better, Australian shares or Australian property? Nine out of ten will say that property prices have run circles around Aussie stocks.

Australian property values have certainly soared. But their stock market hasn’t been too shabby, either.

According to Philip Soo, a Master’s research student at Deakin University’s School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Australian property prices rose 400 times faster than inflation between 1900 and 2012.14 He sourced such data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Over the same 112 years, Australian shares have risen 2,208 times faster than inflation. Both asset classes have also done well over the five-year period ending May 31, 2016. According to GlobalPropertyGuide.com, the average house price change measured over eight capital cities saw an increase of about 28 percent.15 Vanguard’s Australian stock market index increased by 37 percent.

Australians who want a diversified portfolio of indexes could also choose Vanguard. Vanguard Australia offers five Life Strategy funds. They rebalance each of them once a year. The investment costs (as a percentage of the overall assets) decreases as each account grows.

Each of Vanguard’s Life Strategy funds, which I’ve listed in Table 7.9, cost 0.9 percent per year for the first $50,000 invested; 0.6 percent for the next $50,000 and 0.35 percent for balances above $100,000.

Table 7.9 Vanguard Australia’s Life Strategy Funds

| Fund | Percentage in Stocks | Percentage in Bonds | This fund is best suited for . . . |

| Vanguard Life Strategy High Growth Fund | 90.2% | 9.8% | Aggressive and young investors |

| Vanguard Life Strategy Growth Fund | 70.3% | 29.7% | Moderately aggressive and young investors |

| Vanguard Balanced Index | 50.2% | 49.8% | Conservative investors |

| Vanguard Life Strategy Conservative Fund | 30% | 70% | Very conservative investors |

Source: Vanguard Australia

Intelligent Investment Firms on the Rise

Several intelligent investment firms (robo-advisers) are set to challenge Vanguard. I’ve listed some below. Costs vary, as do their services. But over time, fees for all of these firms, including Vanguard’s, could get reduced as competition ramps up.

Each of the firms listed in Table 7.10 builds and rebalances portfolios of exchange-traded index funds. Fees differ based on the amount that’s invested. For example, Stockspot doesn’t charge an annual fee for the first 12 months on accounts that are valued below $10,000. They charge 0.924 percent per year for accounts valued below $50,000. They charge 0.528 percent per year for accounts valued above $500,000.

Table 7.10 Intelligent Investing Firms In Australia

| Firm | Annual Fee | Additional Annual Percentage on Assets Fee | Estimated Total Annual Fees Including Fund Expense Ratio Costs |

| Stockspot | $77 | 0.528% to 0.924% | 0.828% to 1.224% |

| Ignition Wealth | $198 to $396 | 0 | 0.3% |

| Proadviser | $75 | 0.79% | 1.09% |

| Quietgrowth | $0 | 0.40% to 0.60% | 0.70% to 0.90% |

| Vanguard’s Life Strategy Funds | $0 | 0.35% to 0.9% | 0.35% to 0.9% |

Let me further explain the above table. Stockspot charges a $77 fee per year to every account holder. They then charge the client a percentage of the account’s value each year. Depending on the account size, that ranges from 0.528 percent to 0.924 percent per year. But the fund companies charge small fees for their ETFs. Stockspot doesn’t take this money. It would go to Vanguard, iShares, or the chosen ETF provider. When adding these estimated fund charges, investors would pay the annual $77 per year plus 0.828 percent to 1.224 percent of their account values each year, depending on their account size.

Ignition Wealth offers a great deal for investors with larger accounts. It charges a flat fee between $198 and $396 per year. That fee would eat aggressively into a small investment account valued below $10,000. But Ignition Wealth doesn’t charge an annual fee based on the investment account size. It reminds me of what a friend once told me about his Jaguar sports car. “Anyone can keep up with me up to 60 miles per hour. But God help anyone who tries to keep up after that.”

Intelligent Investment Firms in Singapore

In late 2016, a couple of robo-advisers were getting ready to launch in Singapore. One of them is called Smartly. They promise to build portfolios of low-cost ETFs.

This is a big, positive step. Singaporeans deserve a low-cost platform for a portfolio of index funds. But if such firms take shortcuts, somebody might get bit. Based on e-mail exchanges that I have had with these firms, they are planning to use some US-based ETFs.

For taxable reasons, that’s a dangerous game to play. It’s like saying, “We care about our investors. But let’s toss their heirs in front of an MRT train.” Such firms should build portfolios of ETFs that trade on the Singaporean, Canadian, British, or Australian stock market.

Here’s why.

If a Singaporean dies owning US-based assets, the investor’s heirs may have to pay a hefty US estate tax bill if their assets exceed the equivalent of $60,000 USD.

I can hear what you’re thinking. “I’m not an American. I’m not even using a US brokerage.” That might not matter. The IRS states that “Nonresident’s stock holdings in American companies are subject to estate taxation even though the nonresident held the certificates abroad or registered the certificates in the name of a nominee.”16

And the tax could be hefty, starting at 18 percent and rising to 40 percent for accounts exceeding $1 million.17

Table 7.11 lists three portfolios. Each has similar asset allocations that provide exposure to US stocks, international stocks, and international bonds. US estate taxes could slap the first portfolio once the investor dies. But the other two would be safe because the ETFs trade on the Canadian and UK stock exchanges.

Table 7.11 Singaporeans, Why Take The Extra Risk?

| Could Be Subject to US Estate Taxes | Would Not Be Subject to US Estate Taxes | Would Not Be Subject to US Estate Taxes | |

| US Equity | Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI) | Vanguard US Total Market ETF (VUN) | Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VUSA or VUSD) |

| International Equity | Vanguard FTSE Developed Markets ETF (VEA) | Vanguard FTSE Developed Markets ETF (VDU) | Vanguard FTSE Developed World ETF (VEVE or VDEV) |

| Fixed Income | iShares 1–3 Year International Treasury Bond ETF (ISHG) | Vanguard Global (ex US) Bond ETF (VBG) | iShares Global Government Bond UCITS ETF (IGLO) |

| Trading Exchange | US | Canadian | UK |

Don’t let a teething robo-adviser in Singapore threaten the money you could bequeath. If you do use such a firm, make sure they don’t build you a portfolio with an ETF that trades on a US stock exchange.

Don’t Ask about Another Lover

What would happen if a man asked his lover about the seductive woman who lives across the street? “Should I make the switch?” he might ask. If he asks such a question, he should record his stupidity and upload it onto YouTube.

He would get millions of hits if he got beaten to a pulp.

That won’t happen if you ask your financial adviser about index funds. But the same rule applies. If the adviser invests using actively managed funds, she’s not going to be happy.

She’ll also be armed with a handful of arguments to keep you away from index funds. In the next chapter, I explain what she’ll say. It’s always best to peek inside a pilferer’s playbook.