Chapter 6. Communication

Chapter 3 explores the origin of ideas, and Chapters 1 and 2 explore their storage and retrieval. In between, however, there is another step: communication. If an idea in your brain did not originate there, it sprang from the creative act of another person, was imparted to you via communication, and only then was stored in your brain via memory.

This chapter is all about communicating clearly, cryptically, creatively, and in other ways. Whether you’re interested in getting your point across, concealing information from your enemies, or thinking and expressing yourself in novel ways, this chapter has hacks for you.

Put Your Words in the Blender

It may seem counterintuitive, but you can be more expressive if you squish and mangle your language.

James Joyce wrote his last book, Finnegans Wake, in a language for the

third millennium, a language of dreams. He called it nat language, a phrase that blends

night language and not

language. I call it Bl![]() nder, a blend of blender and

blunder, because it mixes up words and people

sometimes speak it by mistake.

nder, a blend of blender and

blunder, because it mixes up words and people

sometimes speak it by mistake.

Consider Lewis Carroll’s (another master of Bl![]() nder) description of portmanteau words:

nder) description of portmanteau words:

Take the two words “fuming” and “furious.” Make up your mind that you will say both words, but leave it unsettled which you will say first. Now open your mouth and speak. If your thoughts incline ever so little towards “fuming,” you will say “fuming-furious;” if they turn, by even a hair’s breadth, towards “furious” you will say “furious-fuming;” but if you have the rarest of gifts, a perfectly balanced mind, you will say “frumious.”1

Bl![]() nder cannot represent reality perfectly, but it

approximates it more closely than ordinary language does. Think of it as

linguistic antialiasing or, to mix a metaphor (since we’re mixing

everything else), a linguistic triangulation on the object of

discussion, pinpointing it along a fuzzy word spectrum [Hack

#34].

nder cannot represent reality perfectly, but it

approximates it more closely than ordinary language does. Think of it as

linguistic antialiasing or, to mix a metaphor (since we’re mixing

everything else), a linguistic triangulation on the object of

discussion, pinpointing it along a fuzzy word spectrum [Hack

#34].

Paradoxically, by blurring the boundaries between words, a portmanteau such as frumious is closer to a certain state of mind (frumiousness) than ordinary English words (furious, fuming) can ever be.

In Action

Most people find Finnegans Wake hard to understand; some consider it mere nonsense. If you examine it closely, however, it uses a form of semantic data compression. Consider the following sentence from the book:

When a part so ptee does duty for the holos, we soon grow to use of an allforabit.2

You can interpret this in a number of ways, all of which can be correct. Ptee means petit, French for small, but also p-t, the letters of the alphabet. Allforabit is a blend of alphabet and all for a bit. When we understand that holos is Greek for whole, we are ready to interpret this sentence as something like this:

When such a small unit as a letter or word does duty for entire objects, we soon grow to use, and grow used to, an alphabet. When small parts do duty for the whole, we soon grow to use (and grow used to) representing everything at once by a small part.

This sentence is Joyce’s critique of language: we cannot represent

reality accurately, because any use of p and

t is bound to reflect only a fragment of it. It

is also his praise of language (we can do so much with so little), and

his description of how nat language or

Bl![]() nder works.

nder works.

The passage is also a good example of the seeming prescience of the Wake. I’m not going to claim that Finnegans Wake has magic powers, but I will point out Joyce’s use of seemingly up-to-the-moment words such as bit (as in 0 or 1, the basic unit of information) and holos, which could be taken as the plural of holo or hologram. The fact that these words, and such postmodern concerns as the relationship of part to whole and information to reality, appear in a book written so long ago suggests to me that it still has much to offer in the 21st century.

How It Works

Paronyms are words that are spelled or pronounced somewhat differently from each other and have somewhat different meanings. If you combine two paronyms, you can create a blend—or as Carroll called it, a portmanteau.

Some research has been done on paronymic blending by psychologists studying production errors in speech, such as malapropisms (speech errors involving paronymic substitution, such as “Stop that! You’re making a speculum of yourself!”). Malapropisms are common among words that sound similar, have the same number of syllables, and are stressed identically.3

This suggests that phonologically similar words are stored near one another in the human neural

lexicon. Researchers have suggested that blending “errors” occur when two words in the lexicon,

such as imposter and

impersonator, are similar semantically and enter

into the later stages of sentence production together, forming a

portmanteau like

imposinator.4 Since

semantically and phonologically similar words seem to be stored near

one another in the brain, it might be possible to learn to communicate

fluently in Bl![]() nder.

nder.

But what if people don’t understand the blends? Certainly,

ordinary static language might be needed for technical communication.

In other situations, people could blend at will, and explain their

blends in ordinary language if necessary. Successful blends might be

reused, and the vocabulary of Bl![]() nder would grow.

nder would grow.

Eventually, Bl![]() nder might be able to describe in a word a

freeform emotion, state of mind, or other complicated phenomenon that

would require a sentence of ordinary language. Dictionaries of

neologisms and foreign words (not necessarily blends),

such as They Have a Word for

It,5 The Deeper

Meaning of Liff,6 and

Family Words,7 do this

already

nder might be able to describe in a word a

freeform emotion, state of mind, or other complicated phenomenon that

would require a sentence of ordinary language. Dictionaries of

neologisms and foreign words (not necessarily blends),

such as They Have a Word for

It,5 The Deeper

Meaning of Liff,6 and

Family Words,7 do this

already

Why not increase the expressiveness of our language, by using and spreading these and other new words?

In Real Life

Here are a few Bl![]() nders I’ve collected over the years.

Swet dreams was produced with a “perfectly

balanced mind” when wishing someone goodnight, and I actually believed

when I was a boy that pless was a common

word.

nders I’ve collected over the years.

Swet dreams was produced with a “perfectly

balanced mind” when wishing someone goodnight, and I actually believed

when I was a boy that pless was a common

word.

- Fashist

Fashion fascist: one who aggressively promotes his own style of dress or anything else

- Pless

To press something into place

- Sedase

To seduce by sedation, or sedate by seduction

- Swet dreams

Sweet, wet, sweaty dreams

Bl![]() nder is not the province of only great writers

of literature such as Joyce and Carroll. Everyone can use it to blur his language and at

the same time enhance its precision. One English translation of the

Joycean phrase nat language is night

language, and Finnegans Wake depicts an epic

dream, so Joyce might have used a tool such as onar [Hack #28] to learn how to

blend fluently. It worked for me.

nder is not the province of only great writers

of literature such as Joyce and Carroll. Everyone can use it to blur his language and at

the same time enhance its precision. One English translation of the

Joycean phrase nat language is night

language, and Finnegans Wake depicts an epic

dream, so Joyce might have used a tool such as onar [Hack #28] to learn how to

blend fluently. It worked for me.

So try onar. Keep a dream diary [Hack #29]. Read Finnegans Wake. Practice punning. Blend a few paronyms. A new form of language might be near.

End Notes

Carroll, Lewis. The Hunting of the Snark. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext91/snark12h.htm.

Joyce, James. 1939. Finnegans Wake. http://www.trentu.ca/jjoyce/fw-19.htm.

Fay, David, and Anne Cutler. 1977. “Malapropisms and the structure of the mental lexicon.” Linguistic Inquiry, 8(3): 505–520.

Foss, D. J., and D. T. Hakes. 1978. Psycholinguistics: An Introduction to the Psychology of Language. Prentice Hall.

Rheingold, Howard. 2000. They Have a Word for It: A Lighthearted Lexicon of Untranslatable Words and Phrases. Sarabande.

Adams, Douglas, and John Lloyd. 1990. The Deeper Meaning of Liff. Three Rivers Press.

Dickson, Paul. 1998. Family Words: The Dictionary for People Who Don’t Know a Frone from a Brinkle. Broadcast Interview Source, Inc.

See Also

Some fans of Finnegans Wake tend to praise it excessively. (You might even think I’m one of them.) As an antidote, Stanislaw Lem has provided a marvelous satire in his collection A Perfect Vacuum (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich). The Wake compacts all of history into the single nightlong dream of an innkeeper; Lem’s imaginary book Gigamesh compresses it into the 36 minutes it takes a condemned man to walk to the gallows.

Allan Metcalf has an excellent book called Predicting New Words: The Secrets of Their Success (Houghton Mifflin Company). He writes, “Whether a new word survives does not depend on whether it fills a perceived gap... [nor] on whether it is useful... [but] rather on whether the word resonates with the speakers of a language, and that depends on a number of factors...” He spends much of the rest of the book exploring those factors.

Learn an Artificial Language

Since the language you speak influences your thoughts, speak some unusual languages and open your mind to unusual thoughts.

A conlang is a constructed language, more commonly known as an artificial language. Unlike C and Java, which are artificial languages created by humans for computers to use, conlangs are created by humans for humans to use.

Over the centuries, hundreds of conlangs have been created, and certainly many more projects that are private have never been published. Many conlangs were created with a specific purpose in mind, such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s Elvish languages Sindarin and Quenya, which were created for their sheer beauty. Others were created for a laugh or to be used in movies or books.

Some languages are working languages, however, designed to liberate and empower human minds in a specific way. Esperanto, for example, was designed to break down cultural barriers between people of different cultures, and Lojban was designed to remove as many limitations on human thought as possible.

In Action

Here are six well-known constructed languages that can help you think and express yourself in novel ways.

Esperanto

Esperanto is the most widely spoken conlang on Earth, with an estimated 2 million speakers, putting it on par with Lithuanian, Icelandic, and Hebrew.1 It was designed in 1887 by Dr. L.L. Zamenhof as a kind of neutral, universal second language that would allow native speakers of all languages to meet one another on even ground, with none having an intrinsic fluency advantage.

Esperanto is extremely simple, regular, and easy to learn. It’s also extremely flexible. To quote Esperantist Ken Caviness, “It’s been used in all conceivable circumstances for over 100 years. Whatever you have to say, you can say it in Esperanto.”

One common complaint about the vocabulary of Esperanto is that it is too Indo-European, and most Esperanto words do indeed come from West European languages. However, Esperanto’s agglutinative grammar is more akin to other language families. In any case, Esperanto speakers come from all over the world—it’s especially popular in China—and I have had mind-opening, preconception-destroying conversations on many subjects with people from many lands in Esperanto.

Esperanto has a wealth of translated world literature, and it can literally open doors for you with its Pasporta Servo, an amazing international hospitality service of friendly people in many different countries who make free lodging available for traveling Esperantists. A wide variety of Esperanto learning materials is available on the Web, as are volunteers who will teach it to you free of charge via email. If you’re waiting for an engraved invitation to the world, one of those could probably be arranged, too—with an Esperanto postage stamp.

Lojban

Lojban is an elaborate constructed language that was designed to test the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (see the “How It Works" section of this hack). It’s the more robust descendant of the original Loglan project, which was designed by Dr. James Cook Brown. The project forked because of an intellectual property dispute; you might say Lojban is to Loglan as GNU/Linux is to Unix.

Lojban is designed to remove as many restrictions as possible on “creative and clear thought and communication.” To this end, its grammar is based on propositional logic, and it has a culturally neutral vocabulary that was algorithmically derived from the six human languages with the most speakers (Mandarin Chinese, English, Hindi, Spanish, Russian, and Arabic).

Lojban’s grammar is more regular than even Esperanto’s, so much so that it can be fully specified on a computer with a program such as YACC. This highly regular grammar leads to Lojban’s famous audiovisual isomorphism, meaning that spoken Lojban can be unambiguously transcribed; you even pronounce punctuation. Lojbanists speculate that this feature might be useful for human-computer communication. Science fiction has beaten them to it, however; the characters in Robert Heinlein’s 1966 novel The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress use Loglan for just that purpose.

In short, Lojban is a kind of super-language designed to shoot off your Sapir-Whorfean linguistic shackles and blow your mind open. Give it a try.

Klingon

Klingon is another popular conlang. Professional linguist Marc Okrand developed it for the Star Trek movies, as the language of the Klingons, an alien race.

Dr. Okrand explicitly designed Klingon to be alien, to stretch the human brain by violating human linguistic universals. For example, its syntax uses a word order seldom observed among human languages. Dr. Okrand has a puckish sense of humor and has added other features that are hard for humans to wrap their minds, lips, and larynxes around, but despite this, Klingon has a devoted fan base.

Here’s an example of how Mark “Captain Krankor” Mandel, Chief Grammarian of the Klingon Language Institute, hacked his mind with Klingon. You can, too!

Mandel offers a story about the way Klingon makes him feel. During one of the annual qep’a’, he went out on a mission to pick something up for the convention. A light rain was falling; he felt wet, tired, and a little droopy. But he strengthened his resolve by saying a Klingon phrase to himself: jISaHqo’, which he says could be translated as “I refuse to care,” “I will not care,” and “I refuse to let this bother me.” In English he would only have had the weaker phrase, “I don’t care,” which wouldn’t have conveyed the strength of his intentions. He smiles at the memory. Thinking in Klingon reminded him that being irritated by a little rain was the sort of thing only a foolish human would do.2

AllNoun

More a constructed grammar than a constructed language, Tom Breton’s AllNoun has a vocabulary and a grammar that consist entirely of English nouns, thus embodying an idea first proposed in Jack Vance’s 1958 science fiction novel, The Languages of Pao.

An AllNoun sentence is a web of relationships with a weirdly static, timeless feel. Here’s an example of a sentence written in AllNoun:

act-of-throwing:whole Joe:agent ball:patient

And here’s a rough transliteration:

In some context, there is an act of throwing, and the agent of that act is Joe, and the patient is some ball.

which conveys this basic intended meaning:

Joe throws the ball.

You might think that act-of-throwing is an attempt to smuggle a verb into the sentence, but in a full constructed language, as opposed to the prototype project that AllNoun is, that hyphenated word would be a timeless, tenseless noun in its own right.

With only one part of speech, AllNoun’s grammar is extremely simple. Paradoxically, if you try hacking your mind with AllNoun, you might find its simplicity to be the most difficult, yet most rewarding, aspect of this language.

Solresol

Solresol was developed in 1817 by Jean Francois Sudre. It was the first international auxiliary language comparable to Esperanto to receive serious attention. Its most salient feature is that it is composed entirely of musical notes. For example, its name, which means simply language, consists of the notes sol-re-sol from the Western solfege scale (do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti (or si), do).3

Although the principle of forming antonyms by reversing the notes in a word is interesting (for example, fasimisi means advance and simisifa means retreat), there’s probably not much in Solresol to broaden your mental horizons.

Its real value instead comes from enabling you to communicate multimodally. You can express Solresol syllable-notes via singing, playing a musical instrument, flashes of light, semaphore, spoken language, written language, musical notation, and so on. You can even use it to add another information “channel” for modifying the meaning of verbal language.

How It Works

The controversial Sapir-Whorf hypothesis4 states that there is a direct relationship between the categories that are available in a language and the way the speakers of that language think and act. While if it were true that language completely determined thought, people would never have any thoughts that they could not express (and we know that’s not true), there have nevertheless been some suggestive experiments in this area. For example, it was recently shown that one Amazonian tribe without words for numbers greater than two cannot count reliably higher than two or three.5 Skeptics have pointed out that causation may run the other way: the tribe never developed words for numbers because they never needed to develop the concepts.6

As mentioned earlier, Lojban was designed to be a comprehensive test of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis that enabled its speakers to think logically, clearly, and creatively. However, it’s doubtful that there will ever be a full-scale experiment of the sort its designers envisioned, because there may never be many fluent speakers of Lojban, and the number of native speakers is approximately none.

Design Your Own

You can learn a lot about language and the human mind by creating your own language. Does that sound audacious? The Language Construction Kit web site7 by Mark Rosenfelder explains how to create your own language sounds, alphabets, words, grammar, even speaking and writing style, as well as an imaginary history for your language, and a family of related languages.

Here are a few tips for doing so, partially inspired by Newitz and Palmer’s flowchart in The Believer 8 but mostly indebted to the Language Construction Kit. For a crash course in linguistics and cross-cultural human thought styles, and much more information than I can possibly convey here, please visit that site.

Models

First, you’ll need a basic model and approach for designing your new language:

Decide whether you want your language to be “natural” (full of irregularities, like English), or “unnatural” (simple and logical, like Esperanto and Lojban).

Steal from some languages very different from English, such as Quechua, Swahili, and Turkish.

Sounds

Give some thought to how you want your language to sound when spoken:

Learn something about the disciplines of phonetics and phonology, so as not to make newbie mistakes with the sounds of your language.

Learn about how vowels and consonants work, including how to invent new ones.

Decide how your language stresses words.

Decide whether your language uses tones (like Mandarin Chinese) and, if so, how they work.

Design your conlang’s phonological constraints. For example, tkivb could never be an English word, but it might be OK in another language.

Are you designing a language for aliens? If so, make sure your conlang sounds really weird.

Alphabets

Every written language needs an alphabet, the basic building blocks of words:

Develop a Roman orthography—that is, a way of spelling your language with the Roman alphabet.

If appropriate (for example, for a fantasy language), develop a new alphabet, too.

Use diacritics and accent marks if you want, but not haphazardly.

Alternatively, invent pictograms, logograms, a syllabary, or some other way of writing your language.

Word building

Once you’ve got your alphabet, consider how the letters will be used to form words:

Determine whether you want a small or a large vocabulary.

Develop a vocabulary that respects your conlang’s phonological constraints. You can write a computer program to generate random words within those constraints.

Determine whether you want to borrow words from other languages a little, a lot, or not at all.

Decide whether your language uses onomatopoeia and other sound symbolism (e.g., buzz, tinkle, gong, rumble, etc.).

Be careful not to just reinvent English idioms.

Grammar

Grammar is one of the most complex aspects of a conlang, and even the Language Construction Kit doesn’t address it fully. Here are a few issues you’ll have to face:

Determine whether you have nouns, verbs, and adjectives. (Lojban makes do with one part of speech for all three, and adverbs, too.)

Determine your pronouns: I, you, he, she, it, and many more are possible.

Determine the order in which parts of speech appear in sentences (in English we use SVO, or subject-verb-object).

Style

Give your language a distinct personality and feel:

How is politeness expressed in your language?

What forms does poetry use in your language? Rhyme and meter? Alliteration, as in Old English? Counting syllables, as in Japanese haiku?

Language families

Assign your language to a group of speakers:

If your language belongs to an imaginary people, is it derived from other imaginary languages? Tolkien’s languages were related in a huge imaginary tree.

Does your language have dialects?

Speaking and writing

Once you’ve created your language and formed a group, get communicating!

End Notes

Esperanto: Frequently Asked Questions. 1999. “How many people speak Esperanto?” http://www.esperanto.net/veb/faq-5.html.

Newitz, Annalee. 2005. “The Conlangers’ Art.” The Believer, May 2005. http://www.believermag.com/issues/200505.

Wikipedia. 2005. “Solfege.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solfege.

Wikipedia. 2005. “Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sapir-Whorf_Hypothesis.

Gordon, P. 2004. “Numerical Cognition Without Words: Evidence from Amazonia.” Science, 306: 496–499. http://faculty.tc.columbia.edu/upload/pg328/GordonSciencePub.pdf.

Gordon, P. 2005. “Author’s Response to ‘Crying Whorf’.” Science, 307: 1722.

Rosenfelder, Mark. 2005. “The Language Construction Kit.” http://www.zompist.com/kit.html.

Newitz, Annalee, and Chris Palmer. 2005. “Build Your Own Conlang.” The Believer, May 2005. http://www.believermag.com/issues/200505.

See Also

Communicate less judgmentally and more dispassionately with E-Prime [Hack #52].

Write faster with Dutton Speedwords [Hack #14].

Expand your idea space [Hack #34] and express fine shades of meaning not present in English with neologisms [Hack #50].

Learn more about Esperanto at http://www.esperanto.net.

Learn more about Lojban at http://www.lojban.org.

Learn more about Loglan at http://www.loglan.org.

Learn more about Klingon at http://www.kli.org.

Learn more about AllNoun at http://www.panix.com/~tehom/allnoun/allnoun.htm.

Learn more about Solresol at http://www.ptialaska.net/~srice/solresol/intro.htm.

Communicate in E-Prime

Eliminate the verb “to be” from your communication to become less dogmatic. Easy to learn, hard to master.

Although almost anyone can speak dogmatically without using the verb “to be” and also speak calmly and rationally with it, many people have found that eliminating “to be” from their speech and writing makes it easier to communicate flexibly and nondogmatically.1

Alfred Korzybski, the founder of the discipline of general semantics, thought that the verb “to be” could lead to confused thought, confused action, and even fascism. Because so much of fascism consists of vilification of the enemy, and because so much of vilification of the enemy consists of calling them subhuman, identifying them with the forces of evil, and so on, fascists might find it hard to write propaganda without “to be.”

Korzybski considered the use of “to be” as an auxiliary verb (“I am going next door”) fairly innocuous, as well as several other uses. He primarily objected to two uses of the verb “to be,” which he called identity and predication.

- Identity

“That is a spaceship!” (Implication: call out the National Guard! Get the White House on Line 1!)

- E-Prime alternative

“That certainly looks like a spaceship to me.” (Implication: it merits further investigation. What does it look like to you?)

- Predication

“Fred is disgusting.” (Implication: ostracize him!)

- E-Prime alternative

“I don’t like Fred; I find him disgusting.” (Implication: but maybe you like him. What do you like about him? Let’s talk.)

Of course, “I find Fred disgusting” contains an implicit form of the verb “to be”:

I find Fred to be disgusting.

Readers might raise other objections. For example, Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy [Hack #57] questions the utility of “rating” human beings at all, instead of their behavior. Even complimenting another person with “to be” can have harmful effects. When you rate someone by saying “he is a good person,” presumably someone else “is a bad person” by comparison—and how will you feel if you rate yourself that way? REBT categorizes rating as a form of labeling and overgeneralization [Hack #58].

Thus, perhaps we should scope the sentence this way instead, criticizing Fred’s behavior rather than his total being:

I find Fred’s constant nose picking and opera singing obnoxious. (On the other hand, I quite like his kindness toward animals.)

Then again, we can consider becoming aware of dogma and absolutism the main thrust of E-Prime, and permit the use of “to be,” properly scoped:

Fred’s constant nose picking and opera singing are obnoxious to me.

By itself, such scoping (“obnoxious to me“) might represent an improvement in most people’s everyday speech and thought. You can treat E-Prime as a tool, whipping it out of your mental toolbox [Hack #75] and putting it away when done. You need not speak or write in E-Prime all the time, although some people do attempt to.

In Action

To use this hack, simply eliminate all uses of the verb “to be” from your communication for a given period of time, whether an hour, a day, or the time it takes you to write an email that you fear will turn into a flame.

People who speak E-Prime often choose to eliminate all forms of “to be” rather than just the so-called is of identity and is of predication. D. David Bourland, Jr. (inventor of E-Prime) and E.W. Kellogg III liken this to the situation faced by someone trying to quit smoking: although the health benefits of cutting down from two packs of cigarettes a day to just two cigarettes a day might amount to almost as much as quitting entirely, almost no one can do it. Similarly, many people who choose to speak E-Prime eliminate “to be” cold turkey because they find it easier than analyzing each use of “to be” to see whether it involves identity or predication.2

As a further exercise, you can try to catch writers in the use of particularly unjustified uses of “to be”; it will alert you to other people’s propagandistic appeals and hone your awareness of your own use of the Verb That Dare Not Speak Its Name.

Kellogg suggests that once you get better at speaking in E-Prime, you offer your spouse or a close friend $1 every time they catch you using “to be” without immediately correcting yourself.3 As a somewhat less costly alternative, try snapping yourself to attention [Hack #74] with a rubber band on your wrist.

You might also find that eliminating “to be” from your speech and writing forces you to express yourself more creatively. Try it! If this phenomenon interests you, you can experiment more with it by constraining yourself further [Hack #24].

In Real Life

I wrote this hack entirely in E-Prime, except for the examples. Of course, I intended this as a purposeful, rather than arbitrary constraint [Hack #24].

End Notes

Kellogg, E.W., III. 1987. “Speaking in E-Prime: An Experimental Approach for Integrating General Semantics into Daily Life,” Etc., Vol. 44, No. 2. Reprinted in To Be or Not to Be: An E-Prime Anthology, published by the International Society for General Semantics, 1991. http://learn-gs.org/library/etc/44-2-kellogg.pdf.

Kellogg, E.W., III, and D. David Bourland, Jr. 1990. “Working with E-Prime: Some Practical Notes,” in To Be or Not To Be: An E-Prime Anthology.

Kellogg, E.W., III. 1987.

See Also

Wallace, Michal. The e-Primer. http://www.manifestation.com/neurotoys/eprime.pl. A CGI script that checks for uses of the verb “to be.”

Wikipedia entry. “E-Prime.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E-prime. Unusually comprehensive, perhaps a result of Wikipedia’s neutral point of view [Hack #64].

Learn Morse Code Like an Efficiency Expert

Learn the Morse code alphabet and numbers painlessly and efficiently in an hour or less—starting now!

Frank Gilbreth, the industrial psychologist who pioneered efficiency and time-motion studies in the early 20th century, invented a quick and simple way to learn Morse code. Only the first four letters of his Morse alphabet have survived, but this hack reconstructs the rest.

In their book, Cheaper by the Dozen, two of Gilbreth’s children, now grown, describe how they learned Morse code:

For the next three days Dad was busy with his paint brush, writing code over the whitewash in every room... On the ceiling in the dormitory bedrooms, he wrote the alphabet together with key words, whose accents were a reminder of the code for the various letters... When you lay on your back, dozing, the words kept going through your head, and you’d find yourself saying, “DAN-ger-ous, dash-dot-dot, DAN-ger-ous.”1

This might not be the best way to learn Morse code—and understanding it when it is sent to you will certainly take practice—but it is the quickest and simplest method I know of. My family members picked up roughly half the alphabet just by hearing me describe this hack while I was writing it.

In Action

Briefly, the mnemonic for each Morse code letter is a word or phrase beginning with that letter. In Table 6-1, unaccented (unstressed) syllables represent dots in Morse code, and accented (stressed) syllables represent dashes.

Letters

To use Table 6-1, first learn the alphabetic mnemonic associated with each letter, and then reproduce the Morse code for that letter by sounding out the stress in the mnemonic.

For example, the mnemonic for R is

ro-TA-tion. This is the English word

rotation with the stress on the second syllable

indicated by capital letters. Because the stresses in this word run

unstressed-stressed-unstressed, you know that the Morse for R is

.-. (dot-dash-dot).

Numbers

Numbers must be learned somewhat differently, but because they are extremely regular, they are also relatively easy. All numbers in Morse code are five symbols (dots and/or dashes) long, and the number of dots corresponds to the numeral that is being transmitted, as shown in Table 6-2.

How It Works

This hack is yet another example of the power of mnemonics (your dear, dear friend). Remembering the dry and abstract dots and dashes of Morse code is like having to remember an arbitrary and cryptic series of commands to a computer’s command-line interface. Creating English mnemonics, however, is like adding a graphical user interface on top of the command line. Simply put, it’s like the difference between Windows and DOS.

In Real Life

Why would you want to learn Morse code, anyway? After all, haven’t telephones and email made Morse obsolete? Not at all. Morse code is still useful in a variety of situations ranging from technological breakdown during emergencies to interfacing with the latest technology, such as texting devices.

Emergencies

You can flash Morse code with a mirror, tap it with two kinds of rock, or use many other methods to send a message far, with few resources.

Assistive technology

Anyone with minimal motor control can send Morse by using whatever they can manage—by tapping a finger or blinking, for example.

Secret communication

You can communicate via hand signals where there might be an audio bug, or by quietly tapping in a room where spoken conversation might be noticed.

Rapid communication

In 2005, the Powerhouse Museum of Sydney, Australia, held a contest between two elderly telegraph operators using Morse code and two teenagers using text messaging on their mobile phones. The telegraph operators beat them handily, despite their not using any texting abbreviations—and being 93 years old.3 The Tonight Show duplicated the stunt on American television.4

After these contests occurred, one clever hacker wrote a free (open source) application for Nokia phones that accepts input in Morse code but sends ordinary text messages, thus allowing users to take advantage of Morse speed, even if the recipient of the message cannot understand Morse.5

End Notes

Gilbreth, Frank B., Jr., and Ernestine Gilbreth Carey. 2002. Cheaper by the Dozen. HarperCollins Publishers.

Anonymous. 1972. A Dictionary of Mnemonics. Eyre Methuen. The mnemonics for L and X came from this book, which contributor James Crook made me aware of after I solicited replacements for my own, fairly unimpressive L and X mnemonics. As it’s a rare British book, I haven’t seen it yet myself.

Dybwad, Barb. 2005. “Morse code trumps SMS in head-to-head speed texting combat.” http://www.engadget.com/entry/1234000463042528.

Video clip from The Tonight Show; http://www.makezine.com/blog/archive/2005/05/video_morse_cod.html.

“Morse Texter.” 2005. http://laivakoira.typepad.com/blog/2005/05/morse_texter.html.

See Also

See the excellent Morse code page in the Wikipedia for information on niceties such as word and sentence spacing and timing, punctuation, special symbols, accented letters, abbreviations, and so on: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morse_code.

Harness Stage Fright

At some point, nearly everyone has to speak to a group about something, but most of us find ourselves overwhelmed with fear when the time comes. However, if you reduce the fear to a manageable level, you can channel its energy into making your presentations more powerful.

If someone walked up to you today and asked you to give a lunchtime talk about your favorite hobby tomorrow, how would you feel? If you’re like most people, you’d probably think fast about an excuse to get out of it, and if you couldn’t, you’d lose sleep tonight. Public speaking is terrifying to many people, even in such a low-pressure setting and with a topic that we find pleasant.

Because so many people fear public speaking, overcoming and harnessing that fear can give you a distinct advantage. It’s a powerful skill, and it comes into play for almost everyone at some time in their lives. Most businesspeople will be called on to give a presentation about something in their careers, for example. Even if you don’t have that kind of job and aren’t an actor, stage fright can sneak up on you if you attend a meeting of your church or neighborhood association, take a class and need to ask questions, or decide to lead a Girl Scout troop.

Tip

Even writer’s block can be a form of stage fright, proving that you don’t need to face a roomful of people to use these techniques.

In Action

The best basic strategy to handling stage fright is to first reduce it to a manageable level and then to use what’s left to make your performance more powerful—to give you “stage presence.” You should perform some of the following techniques well ahead of time, some soon before you speak, and some right before you start and during your performance.

Make notes

As far ahead of time as you can, make notes and know them. Take time to organize your thoughts ahead of time. You’ll reap huge benefits from this in terms of reducing your fear when it’s time to speak. You don’t have to write the whole thing out (and sometimes you won’t really have time), but even a few keywords or an outline will help you find your place if you start to panic. It will also help you be sure that you say everything you want to say without repeating yourself and that you present your ideas in a logical order.

Don’t procrastinate about making your notes, because you’ll want to give yourself some time to use them in preparation. After you make your notes, take some time to go over them so that you know what’s there.

Pay special attention to the beginning and end of your talk and any transitions between sections. Knowing the beginning well will help get you over the obstacle of getting started without panicking; transitions will help you move on if you need to; and knowing the end will help you leave the audience with a good impression, no matter what happens in the middle of the presentation.

Imagine pitfalls

Think about things that could possibly go wrong and figure out an emergency plan. Some people avoid thinking about anything that could go wrong because they think it will make them panic. It can be a little scary to imagine potential problems, but there are two main reasons to do so. The first is to use it as a “dress rehearsal” so that you can figure out ahead of time what you might do in case of trouble. Then, you don’t have to worry so much about the problems, because if one crops up, you already know how to react.

The second reason to imagine what could go wrong is to gain perspective. When it comes down to it, the worst that can happen is usually not that bad. Seldom is a life hanging in the balance on the effects of what you’re getting ready to say. Most of the time, the worst that can happen is that you’ll be slightly embarrassed if something goes wrong. Given how many times all of us are embarrassed in our life, that’s hardly a dire threat. Some of the other hacks in this book can be tremendously helpful in disarming irrational fears, such as learning about the ABC model of emotion [Hack #57] and learning to avoid cognitive distortions [Hack #58].

Remove sources of stress

Anticipate trivial and tangential sources of stress and anxiety, and remove them in advance. In other words, don’t make it any harder than it has to be. Make sure you get enough sleep the night before you speak. Make sure you eat a little beforehand, but not too much. Make sure your clothes are clean and appropriate, and that your appearance is acceptable.

Take care of all the little details that can leach away your attention and energy, so you can focus on the task at hand. Many of these basic concerns, such as paying attention to sleep, nutrition, and exercise [Hack #69], will also improve your general brainpower.

Consider your audience realistically

Remember that the audience wants to be on your side—really! We imagine that when we speak, the audience is ready to criticize and humiliate us, waiting for us to make a mistake, poised to laugh at us. In fact, most of the time, people relate to you when they watch you and hope you’ll do well.

To find evidence, you don’t have to go any further than your own imagination. When you see someone speak or act, and they blunder or forget their lines, don’t you find yourself holding your breath for them, and aren’t you happy and relieved when they recover and go on to do well? Most people are like you: they are basically decent people who don’t want to see anyone hurt or humiliated. They’ll feel the same when you’re the one in the spotlight.

Keep perspective

Take yourself seriously, but not too seriously. If you’re going to speak, you have a reason to do so that matters, either to you or to someone else. Respect yourself or whoever asked you to speak, and approach your task with some appreciation that you’ll make an impression. Don’t be diffident and don’t apologize for speaking at all, or for minor glitches such as coughing or stumbling on a word; doing so only takes up time and puts the focus on the mistake, not on what you’re there to do.

On the other hand, again, most of the time your speech isn’t a life-or-death matter, and it’s certainly not going to change history if your tongue trips. Be ready to brush such things off and see the humor in your situation, and you’ll keep the audience on your side.

Mind your body

Just before you go on, work out physical kinks a little. Don’t go into your speech out of breath, but take a moment to stretch, breathe deeply, and even take a little walk before you start. You’ll relax your body, improve your blood flow, increase oxygen to your brain, and make yourself more alert.

Feel your fear

With preparation, you’ve reduced your fear to a more manageable level. Now, go ahead and let yourself feel it a little. Let yourself get excited and feel it physically. Try not to panic, but go ahead and let through some of the sensations.

Reframe your fear

Rethink your fear-induced physical sensations. This is possibly the trickiest part of the hack, and the heart of it.

Now that you can feel some arousal, try to turn it into excitement. Pull your thoughts away from your fears and fix your imagination on your positive goals. Do you want to change someone’s mind with your arguments? Do you want to express something that’s important to you? Do you want to teach people about something you love? Remember that you have an opportunity now, and isn’t that great? Remember what’s causing you to go through with this, even though you’re scared; there must be something behind it that you care about quite a lot.

Slowly, as you realize and picture everything good that could happen as a result of your performance, you’ll feel the fear changing. The feelings won’t go away completely, but with luck and focus, they will turn into a happier sort of excitement, the kind you feel before you do something fun. Blend your passion for your subject matter and your hoped-for results with the excited feelings, and let that fill you and carry you forward. Again, the ABC model of emotion [Hack #57] can help you do this with more sophistication and control.

Use good body language

Be aware of what you’re projecting with your physical self. Hold your head up, walk with confidence, smile if it kills you, and don’t fidget. Looking the part helps you to project your energy as positive confidence and command of the stage, and that’s what your audience will see, even if you’re still scared inside.

Fake it till you make it

In other words, act like a confident speaker, no matter how you feel. Pretend you’re anyone you admire, move as you imagine a confident person moves, speak like that person would speak, and so on.

Not only will you fool a lot of people into believing that you know exactly what you’re doing, but also the effect will work on you, too. Stepping into that person’s shoes actually makes you feel more confident and able as well.

Keep breathing

Force yourself to pause between sentences to take a good deep breath from time to time while you’re speaking. You might think this takes a long time and looks silly, but the odds are that you’re speaking too fast anyway.

Pausing for breath forces you to slow down and think about what you’re doing, check your notes, and generally be present in the moment. Many times, your audience will read your breath as a dramatic pause anyway, which gives more power to what you’re saying. At the very least, it gives them a moment to take in and understand your words. It can also help you reduce stuttering and bad speaking habits like filling every possible pause with “um” or some other sound.

Move on

If something goes wrong, pick up and go on. Dwelling on a mistake only magnifies it. You don’t want to steal focus from what you’re there to talk about, so correct the mistake if necessary, and move away from it as quickly as possible. Don’t fumble, lose your concentration, apologize, or panic further; just move on.

Finish well

Finish as well as you possibly can. No matter what kind of disasters you believe have happened while you were onstage, make the best impression you can at the end. Plan to end your talk with a good story or a strong argument. Never end by saying, “I guess that’s about it,” or something similarly mushy.

Finally, after you’ve said the last thing you have to say, stop talking, look into the audience, and smile. You can then take questions, walk confidently away, sit down, or do whatever you need to do. Just be sure you remain “in character” until you really are off the stage, in whatever form that takes.

How It Works

Why does stage fright grip us so tightly and irrationally? Probably because we form our feelings about it in childhood. Young children speak to people freely and express their thoughts as well as they can, without reticence. However, most of us got our first experience speaking to a group at school. We probably had in the audience a teacher ready to grade our performance and classmates who would certainly make fun of it if we made a mistake or looked silly at all—partly because making fun of us would help quiet their own fears about speaking.

So, we learned to believe that if someone in authority watched us, we would be judged, and that the rest of the audience was hostile and waiting to pounce on any slip-up. Reminding ourselves that we’re reacting to old information that’s no longer relevant to the present situation can help quell those deep-seated fears.

The technique of channeling stage fright into performance power stems from the idea that the body’s state of arousal is interpreted by the mind within a framework of emotional reaction and knowledge about the current situation. Under stress, the body creates a surge of adrenaline, pounding heartbeat, heightened senses, faster breathing, and related reactions. Whether we feel those physical effects as fear, exhilaration, sexual arousal, rage, or something else depends on how we feel at the time and what we believe is going on. It’s part of the reason that some people are turned on sexually by danger or pain, or have a good time at a scary movie or on a frightening roller coaster.

Psychologists Schachter and Singer showed that situational factors cause us to frame physiological effects.1 They gave a mild stimulant to a group of subjects and then placed some of the subjects with a person who exhibited anger and others with someone exhibiting happiness. In both groups, more of the people who had been given the stimulant self-reported strong feelings mirroring the “emotional leader” than those who hadn’t received the stimulant that produced the physiological effects of arousal.

A similar experiment by Dutton and Aron showed how the mind can shift the effects from one kind of arousal to another.2 In this study, an attractive woman interviewed men, some on a swaying rope bridge 200 feet over a river and some on firm ground. During the course of the interview, she gave the men her phone number. More than 60% of the men who talked to her on the rope bridge phoned her afterward, compared to 30% of the men who talked to her on the ground. They had interpreted the heightened arousal level that was produced by the more dangerous situation as greater attraction.

With the techniques in this hack, you’re replicating the effects of these studies intentionally. By consciously reframing physical sensations, we can often convert one emotional reaction to another, in this case transforming fear into excitement that we can transmit through our performance.

In Real Life

I learned a great deal about acting and public speaking in high school and college. I performed in community and semi-professional theater, took acting classes, and competed in public speaking tournaments. I didn’t grow up to be an actor or a professional speaker, but I’ve found the experiences I had and techniques I learned to be invaluable in later life. To name only a few situations where the skills have served me well, I’ve used them to:

Teach informal classes

Participate well in classes as a student

Make a good impact in job interviews

Conquer social anxiety in meeting new people

Persuade groups about issues I found important

In fact, these techniques have become so much a part of me that it was difficult for me to dissect them to write the hack! I consider it some of the most important training I’ve ever had. If you’re a parent, this is also a strong endorsement to encourage your kids to study some acting, debate, and speech techniques while they’re young.

End Notes

Schachter, S., and J. E. Singer. 1962. “Cognitive, social and physiological determinants of emotional states.” Psychological Review, 69: 379–399.

Dutton, D. G., and A. P. Aron. 1974. “Some evidence for heightened sexual attraction under conditions of high anxiety.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30: 510–517.

Marty Hale-Evans

Ask Stupid Questions

At school or at work, we often feel as though we are “drinking from the firehose” when we have to learn a new extensive or complicated subject or task. In these situations, the least stupid thing we can do is ask stupid questions.

Human beings have acquired several different kinds of learning during the course of our evolution. Being able to acquire short-term disposable knowledge (such as where we left our spear) without cluttering up our brain with useless trivia might have been just as important to our survival as learning the long-term skills (such as building a fire or knowing when to plant crops) commonly associated with survival. As modern humans, if we learn something and then forget it before we want to, it might be because our brain never indexed it for long-term use.

Often, this occurs because information is coming at us so fast that our brain just can’t keep up. Studies have shown that our short-term memory can in fact hold only between five and nine items [Hack #11], depending on the information.1 Thus, if your short-term memory is full and you are given new items to learn, your brain will be forced to sacrifice. This hack provides some advice that will help you control the incoming flow of information so that your brain has a chance to index it in your long-term memory.

Learning is something we do, not something we receive. When we are tasked with learning some large, new body of knowledge, it is up to us to control the flow of information we are receiving, to the best that the situation allows. This will allow our brain to process the information and build the deep structures necessary for true comprehension—learning that stays with us, that we can readily recall in the future.

Failure to stem the flow of input can result in frustration, stress, or short-term learning that can’t be called up the next time we need to apply it. It wastes not only our own time, but also the time of the person teaching us.

In Action

In his book Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman writes about his experience teaching a group of students in Brazil:2

One other thing I could never get them to do was to ask questions. Finally, a student explained it to me: “If I ask you a question during a lecture, afterwards everybody will be telling me, ‘What are you wasting our time for in the class? We’re trying to learn something. And you’re stopping him by asking a question.’”

Because all the students were afraid to ask questions, Feynman got highly frustrated and came away convinced that the students were not actually learning anything at all. Too often, in a learning situation, we tend to just nod and allow the instruction to progress without adequate comprehension. Even when we are in a one-on-one learning situation with just an instructor, the temptation to sit passively often results in a monologue. We do this for several common reasons, each of which is a fallacy:

| Excuse | Reality |

| We don’t want to look stupid or waste the class’s time by asking for something to be repeated. | We will look even more stupid if the instructor sees that her time was wasted. |

| There’s a lot of material to cover, and we don’t have time to waste. | We are wasting more time, perhaps even the whole session, if what we’re learning fails to stay with us. |

| We kind of think we understand a concept and assume that it will “gel” later. | Too often, this momentary learning falls by the wayside as we try to take on new knowledge. |

| The instructor might hit upon the part that we don’t understand at a later point. | What if she doesn’t? |

So, what should you do? A much better method is to be active, not passive:

Interrupt your instructor at every step if you are at all uncertain about what you are learning.

Ask stupid questions, even if you feel it’s something you should have picked up already and it might make you look bad.

Make your instructor start again—from the beginning, if necessary—if your understanding is not complete.

Don’t leave dangling pointers—points that you didn’t quite understand, but for which you are anticipating further elucidation. Dangling pointers have a tendency to get lost.

How It Works

Whether we are studying quantum chromodynamics or just making a new friend, a similar process is occurring in our brain. We are building a mental model of the subject we are learning so that we can run mental simulations against it to predict future behaviors. Indeed, the model we build internally should be robust enough for us to predict behaviors that were never described during the initial learning process, if it is to be considered anything other than rote learning.3

Since there is no way to import mental models directly into the brain (not yet, at least!), we must build them piecemeal, as we might assemble a model airplane. To continue the analogy, the instructor is handing you pieces of the model, and you are assembling them internally. If the instructor is handing you pieces too quickly, you will not have time to assemble them. Further, if you assemble part of the model but are unsure about it, there is no point in continuing to add pieces.

In Real Life

At your new job, you are tasked with helping to maintain a large, complex web site. There is a lot to learn: database structures, passwords, server locations, error-reporting procedures, source code revision-control systems, build procedures, and so on. There’s some documentation, but as is usually the case, it hasn’t been kept up-to-date. So, other employees who are familiar with the project have to teach you.

You are eager to impress your new colleagues, so you start learning your new project with vigor. The person walking you through it all is initially impressed as you quickly fly through the different areas you are supposed to learn. You might have missed some finer points, but you don’t want them to think they’ve made a mistake in hiring you, so you stay mum.

You can still repeat back some of the information you’ve been taught, at least at first. But as the days go by, your initial comprehension seems to vanish in the wind, and your co-workers become less impressed as they have to start answering questions about things they’ve already told you about.

What should you have done? You will ultimately be judged by how quickly you are able to contribute to the project, not by how knowledgeable you seem up front. Stupid questions are to be expected, and would have quickly been forgotten. When you’ve had enough for one day, call it quits, and go back and review what you’ve learned so far. Continuing is just a waste of your and your co-workers’ time, and will ultimately reflect poorly on you.

End Notes

Miller, George A. 1956. “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two.” The Psychological Review, 63: 81–97.

Feynman, Richard P. 1985. Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! (page 194). Bantam Books.

Minsky, Marvin. 1985. The Society of Mind. Simon & Schuster, Inc. A collection of short, readable essays detailing how the human brain builds up mental models and how they might be simulated on a computer.

Mark Schnitzius

Stop Memory-Buffer Overrun

The length of a sentence isn’t what makes it hard to understand; it’s how long you have to wait for a phrase to be completed.

When you’re reading a sentence, you don’t understand it word by word, but rather phrase by phrase. Phrases are groups of words that can be bundled together, and they’re related by the rules of grammar. A noun phrase will include nouns and adjectives, and a verb phrase will include a verb and a noun, for example. These phrases are the building blocks of language, and we naturally chunk sentences into phrase blocks just as we chunk visual images into objects.

This means that we don’t treat every word individually as we hear it; we treat words as parts of phrases and have a buffer (a very short-term memory) that stores the words as they come in, until they can be allocated to a phrase. Sentences become cumbersome not if they’re long, but if they overrun the buffer required to parse them, and that depends on how long the individual phrases are.

In Action

Read the following sentence to yourself:

While Bob ate an apple was in the basket.

Did you have to read it a couple of times to get the meaning? It’s grammatically correct, but the comma has been left out to emphasize the problem with the sentence.

As you read about Bob, you add the words to an internal buffer to make up a phrase. On first reading, it looks as if the whole first half of the sentence is going to be your first self-contained phrase (in the case of the first, that’s “While Bob ate an apple”)—but you’re being led down the garden path. The sentence is constructed to dupe you. After that phrase, you mentally add a comma and read the rest of the sentence...only to find out it makes no sense. Then you have to think about where the phrase boundary falls (Aha, the comma is after “ate,” not “apple”!) and read the sentence again to reparse it. Note that you have to read it again to break it into different phrases; you can’t just juggle the words around in your head.

Now try reading these sentences, which all have the same meaning and increase in complexity:

The cat caught the spider that caught the fly the old lady swallowed.

The fly swallowed by the old lady was caught by the spider caught by the cat.

The fly the spider the cat caught caught was swallowed by the old lady.

The first two sentences are hard to understand, but make some kind of sense. The last sentence is merely rearranged but makes no natural sense at all. (This is assuming it makes some sort of sense for an old lady to be swallowing cats in the first place, which is patently absurd, but it turns out she swallowed a goat, too, not to mention a horse, so we’ll let the cat pass without additional comment.)

How It Works

Human languages have the special property of being recombinant. This means a sentence isn’t woven like a scarf, where if you want to add more detail you have to add it at the end. Sentences are more like Legos. You can break them up and combine them with other sentences, or pop them open in the middle and add more bricks.

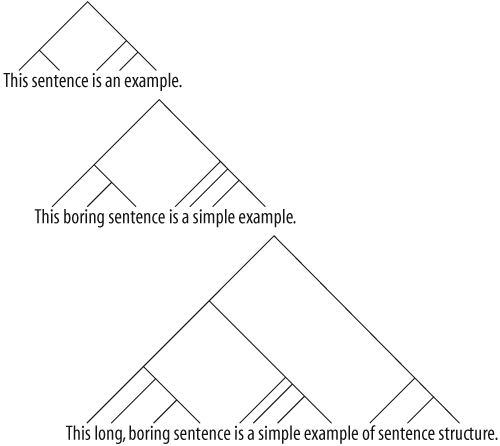

Have a look at these rather unimaginative examples:

This sentence is an example.

This boring sentence is a simple example.

This long, boring sentence is a simple example of sentence structure.

Humans understand sentences by parsing them into phrases. One type of phrase is a noun phrase, the subject or object of the sentence. In “This sentence is an example,” the noun phrase is “This sentence.” For the second, it’s “This boring sentence.”

Once a noun phrase is fully assembled, it can be packaged up and properly understood by the rest of the brain. During the time you’re reading the sentence, however, the words sit in your verbal working memory—a kind of short-term buffer—until the phrase is finished.

Tip

There’s an analogy here with visual processing. It’s easier to understand the world in chunks—hence the Gestalt Grouping Principles. With language, which arrives serially, rather than in parallel, like vision, you can’t be sure what the chunks are until the end of the phrase, so you have to hold it unchunked in working memory until you know where the phrase ends.

Verb phrases work the same way. When your brain sees “is,” it knows a verb phrase is starting and it holds the subsequent words in memory until that phrase has been closed off (with the word “example,” in the first sentence in the previous list). Similarly, the last part of the final sentence, “of sentence structure,” is a prepositional phrase, so it’s also self-contained. Phrase boundaries make sentences much easier to understand. The object of the third example sentence, instead of being three times more complex than the first (it’s three words, “long, boring sentence,” versus one, “sentence”), can be understood as the same object, but with modifiers.

It’s easier to see this if you look at the tree diagrams shown in Figure 6-1. A sentence takes on a treelike structure, for these simple examples, in which phrases are smaller trees within that. To understand a whole phrase, its individual tree has to join up. These sentences are easy to understand because they’re composed of very small trees that are completed quickly.

We don’t use just grammatical rules to break sentences in chunks. One of the reasons the sentence about Bob was hard to understand was that you expect, after seeing “Bob ate,” to learn about what Bob ate. When you read “the apple,” it’s exactly what you expect to see, so you’re happy to assume it’s part of the same phrase. To find phrase boundaries, we check individual word meaning and likelihood of word order, continually revise the meaning of the sentence, and so on, all while the buffer is growing. But holding words in memory until phrases complete has its own problems, even apart from sentences that deliberately confuse you, which is where the old lady comes in.

Both of the first remarks on the old lady’s culinary habits require only one phrase to be held in buffer at a time. Think about what phrases are left incomplete at any given word. It’s clear what any given “caught” or “by” words refer to: it’s always the next word. For instance, your brain read “The cat” (in the first sentence) and immediately said, “did what?” Fortunately the answer is the very next phrase: “caught the spider.” “OK,” says your brain, and it pops that phrase out of working memory and gets on with figuring out the rest of the sentence.

The last example about the old lady is completely different. By the time your brain gets to the words “the cat,” three questions are left hanging. What about the cat? What about the spider? What about the fly? Those questions are answered in quick succession: the fly the old lady swallowed; the spider that caught the fly; and so on.

But because all of these questions are of the same type, the same kind of phrase, they clash in verbal working memory, and that’s the limit on sentence comprehension.

In Real Life

A characteristic of good speeches (or anything passed down in an oral tradition) is that they minimize the amount of working memory, or buffer, required to understand them. This doesn’t matter so much for written text, in which you can go back and read the sentence again to figure it out; but you have only one chance to hear and comprehend the spoken word, so you’d better get it right the first time around. That’s why speeches written down always look so simple to understand.

That doesn’t mean you can ignore the buffer size for written language. If you want to make what you say, and what you write, easier to understand, consider the order in which you are giving information in a sentence. See if you can group together the elements that go together so as to reduce demand on the reader’s concentration. More people will get to the end of your prose with the energy to think about what you’ve said or do what you’ve asked.

See Also

Caplan, D., and G. Waters. 1998. “Verbal Working Memory and Sentence Comprehension.” http://www.bbsonline.org/documents/a/00/00/04/41/.

Steven Pinker discusses parse trees and working memory extensively in The Language Instinct: The New Science of Language and Mind (Penguin Books Ltd.).

Matt Webb and Tom Stafford