Chapter 8. Mental Fitness

Physical fitness is commonly defined as consisting of strength, flexibility, and endurance. You can also think of mental fitness as consisting of these characteristics. Mental strength is the ability to attack a problem, mental flexibility is the ability to stretch your mind to see all of the problem’s aspects, and mental endurance is the ability to keep at a problem until you solve it.

This last chapter puts together everything you learned in the previous chapters. It contains hacks about caring for your brain with sleep, nutrition, and exercise [Hack #69], and mental warm-ups [Hack #66] and mind sports [Hack #67]. Finally, the last hack in the book enables you to integrate all the previous hacks and carry them around in a big, red, mental toolbox [Hack #75] that you can bring with you, even where there is no electricity or pen and paper.

Warm Up Your Brain

Get the blood flowing to your gray matter with a few mental push-ups.

Sometimes the mind simply doesn’t want to think. The morning caffeine hasn’t kicked in yet, or perhaps it is wearing off. Thought seems like an effort. In this situation, you might normally be inclined to wait until the sluggishness wears off, perhaps by taking a break with someone else’s thoughts (browsing the Web, reading a book, or watching TV, for example).

If you would really rather get busy, you might be able to push past the threshold of resistance by doing a little mental warm-up. If thinking is normally a pleasurable activity for you, a small amount of it that requires only a small effort can remind you of this pleasure and motivate you to begin or resume your thinking in earnest.

A good mental warm-up activity is one that is small in scale and gives you at least a small sense of accomplishment. The smallness of scale is important so that the warm-up is easy to begin and easy to end. Ideally, the warm-up will require no preparation so that you can start on a whim.

You must also be able to stop on a whim. Although this might seem like a fast path to abandoning the warm-up in exchange for the web browser, it is important that you be able to stop once you feel mentally alert. This might be difficult if you get too much pleasure out of the exercise or if it involves a goal that you end up wanting to achieve. For this reason, small puzzles (for example, brainteasers) are good for mental warm-ups, but large puzzles are not. A large puzzle (for example, a crossword puzzle) might warm you up (a crossword puzzle is composed of many small puzzles, after all), but it might also suck you in and not release you until you’ve completed the whole thing.

In Action

Here’s a mental warm-up exercise that requires no preparation:

Pick a small (one- or two-digit) number.

Double it in your head.

Double the result, and continue doubling the result until you can no longer keep track of the math in your head or until you feel warmed up, whichever comes first.

Depending on your memory, your skills at mental math, and how long you feel like warming up, you might want to repeat this process when you get stuck, picking a new small number each time.

The initial calculations might be trivially easy, but the difficulty increases as you go along, until you are juggling several numbers in your head and attempting to carry digits without dropping them. Don’t worry about getting the answers right; the process is more important than the result. It will enhance the value of the exercise, however, if you are reasonably sure that your answers are correct. When you are unsure of a result, write it down and start the series again, double-checking your result when you get to the same place. The point here is that satisfaction is the stimulus that warms up your thinking.

Doubling numbers is essentially a mechanical process, so the mental challenge lies in remembering numbers as you apply the process. If doubling numbers bores you, you can try other forms of mental math, such as calculating second powers (i.e., squares). Memory games in general are a good source of mental warm-up exercises. If you are not naturally good with remembering names, for example, you can practice recalling names of casual acquaintances that you haven’t seen in years. If you have used the Dominic System of mnemonics [Hack #6], you can practice it by picking a four-digit number and working out the mnemonic visualizations that go with that number and each successive number until you are warmed up.

Wordplay is another domain with mental-warm-up value. Try composing a limerick or a haiku to get your mental juices flowing. Puzzling out some rhymes or finding just the right words to fit syllable constraints can give you a small challenge and motivate your thinking. Another idea is to form anagrams using words you discover in your immediate environment.

How It Works

In his book Flow,1 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes the feeling of happiness you get when you engage in an activity that is challenging, but not beyond your abilities, and involves a continuous cycle of effort and success. The feeling of accomplishment motivates you to continue your efforts. This is true regardless of the level of challenge, as long as you do feel some sense of actual effort. Even a trivial success rewards your efforts and makes you more inclined to continue. As with the Swiss cheese technique [Hack #65], it is the small bursts of success that kick you out of your lethargy.

The distinction between a mental warm-up and hacks like the Swiss cheese technique is that a mental warm-up has no requirements. It is like stretching before you exercise. You can stretch at any time, and you need no equipment.

Play Board Games

Increase knowledge and hone a wide range of mental skills, painlessly and effectively, by exploring the fast-growing world of modern board gaming.

Maybe you think you know about board games, but if you’re thinking of that Christmas present from your uncle with the pictures from your favorite cartoon on it that you had as a kid, stop right now. This is not your mom’s Monopoly; board games are enjoying a worldwide renaissance in recent years, emerging in an ever-increasing array of sophistication, complexity, and ingenuity. In Germany, the nexus of modern “designer gaming,” board gaming is so popular that a “game of the year” prize, the Spiel des Jahres, is awarded with great public interest. People everywhere and of all ages are getting hip to the fun, challenge, satisfaction, and intellectual development available for the taking by sitting down at a game table.

Modern board games are an excellent way to exercise and develop a variety of mental skills. In almost any game, you can improve your tactical and strategic ability, as well as learn the difference between tactics and strategy, and when to employ both. You can increase your understanding of statistics and probability, learn how to negotiate and make deals with other people, as well as play together toward a common goal, and become more adept at deduction and problem solving.

You can also learn raw information and gain a deeper, more integrated understanding of geography, sociology, military science, politics, and history. Board games can be the laboratory where you put theoretical mental skills into practice and strengthen them under testing and sparring situations. Board games are the dojo where your brain works out and goes from student to ninja. In short, you might get more out of a box of cardboard pieces and bits of wood and plastic than you might ever have dreamed.

In Action

To play board games, you obviously need other players and games. There are a lot of ways to find other players. You can start the old-fashioned way, by asking friends and family to play. See if any of them are interested in having a regular gaming session, once a month or more; it’s a lot easier to sustain interest and build skills by working out regularly.

If you can’t get your current friends to play games regularly, there are established gaming clubs and groups all over. If you live in a reasonably large metro area, you can almost certainly find more than one group to choose from, and even many smaller towns have a group or a game hangout. Try checking the bulletin board at your local game store, or asking the people who work there. If you live near a university, check the bulletin boards there or the student newspaper. You can also place ads or flyers yourself to attract other players; this is how the established groups get started, after all.

As it is with many other things, the Internet is also a terrific source of information about

gaming groups. Use your favorite search engine to search the Web for

your town and "board games", look under board games in

directories like the Open Directory Project, or check blog and email group

sites (such as Yahoo! Groups) for board-game players.

When you find players, you’ll also need games to play. There are a dizzying number of games to choose from nowadays, so this can be daunting for someone trying to get a feel for what’s available. Fortunately, when you find gamers, they’ll usually have favorite games to suggest, so you can try those first to help narrow down your preferences. Nonetheless, once you get some idea of what you like and dislike, start branching out and trying new games on your own. You may well find a game you love that doesn’t fit your other friends’ tastes. You can’t rely on other gamers, though, if you’re starting up with your own friends and all of you are clueless.

Never fear, I’m here to help you out. Many board games fall into a few broad categories. Some fall into multiple categories at the same time. You’ll probably want to try games from all of them to see what you enjoy:

- Classic board games

Includes chess and its variants, Go, checkers (or draughts), Mancala, and Chinese chess. These games have been played for centuries, for good reason; you can’t go wrong by making their acquaintance, and many people spend their lives trying to master them. They’re also some of the most widely played games, so you can almost always find someone to play them, wherever you go. Because they’re elegant, they’re often simple to learn and will challenge basic skills such as strategy building, timing, assessing a situation accurately, and reading an opponent.

- Modern classics

Includes Settlers of Catan, Puerto Rico, Acquire, Cosmic Encounter, Carcassonne, Magic: The Gathering, Tigris and Euphrates, and Reiner Knizia’s Lord of the Rings. These are some of the most popular and well-respected board games in current play. You can usually find gamers who are happy to teach you, and you’re likely to be rewarded by taking the time to learn them. These games come from many categories, so they cover lots of different skills, including tactical and strategic thinking, risk assessment, negotiation, and planning a sequence of actions.

- Card games

Includes classic games such as bridge, hearts, pinochle, and poker, as well as new games such as Schotten-Totten, Frank’s Zoo, Bohnanza, and Set. These games often improve your communication skills, deductive reasoning, and ability to work in partnerships, as well as strategic and tactical thinking.

- Abstract strategy games

Includes games such as Chinese checkers, Blokus, Focus, Othello, Hex, and Twixt, as well as most of the aforementioned classic games. Abstract strategy games are stripped down to the very basics, removing themes and stories to leave stark and elegant mechanics that often turn on mathematical or geometric ideas. Abstract strategy games are good for developing abstract thinking, of course, as well as understanding geometric and math principles and enhancing problem-solving ability.

- Party games

Includes games such as Taboo, Barbarossa, Pictionary, Cranium, and Balderdash. This is the kind of game that you’ll probably encounter most often among friends who game casually. They tend to be less intellectually challenging, but they’re better for building social skills, thinking quickly on your feet, and tuning creativity.

- Strategic historical games

Includes games such as Age of Renaissance, Diplomacy, Advanced Civilization, Risk and its variants, Vinci, Parthenon, and History of the World. In this type of game, you act as leader of a culture or country (or perhaps several), and you must guide your country through historical pitfalls such as invaders, natural disasters, war, and international trade. This category also includes a whole subgenre of historical war games such as Battle Cry, which tend to focus on a specific time and place of military significance, such as the American Civil War. These games tend to be long and complex, but they can be very rewarding, especially in learning long-range strategy, negotiation, and a deeper understanding of the cultural and geographic underpinnings of history and politics.

- Word games

Includes the classics Scrabble and Boggle, as well as newer games such as BuyWord and UpWords. Word games generally have to do with creating and placing words strategically, and they’re excellent for increasing your linguistic understanding of how words are formed, as well as improving vocabulary and flexible thinking.

There are many, many other ways to categorize games, and this is just a start; I considered including sections about financial and auction games, race games, deduction games, and more, organized by game mechanics, themes, or subjective groupings. As you learn more games, you’ll learn what you like and how other games are similar and different, and you’ll have your own opinions about how to group them. There are also lots of wonderful games that don’t fit into categories easily, but I hope this is enough of a map to get you started.

While you’re exploring, there are a few things you should probably avoid, if you want to game with the goal of improving your brain. You probably won’t get much out of “roll the die and move on the track” games; they generally have very simple mechanisms and high luck factors, and really won’t challenge you much. These include the familiar games Sorry and Parcheesi, most popular themed games (such as games based on TV shows), and pretty much anything ending with “-opoly.” You can learn basic facts and random information from trivia games, but most of them have a minimum of strategic potential and won’t challenge those skills very much. Some games of chance are deep and can teach you a lot about strategy and deduction if you learn them seriously—poker is a good example—but many just revolve around the excitement of luck, and those won’t build brain power either.

How It Works

Gaming, as an aspect of play, is rarely taken seriously as an important activity and a worthwhile way to spend time, but research in anthropology and psychology shows that play is an important method for learning and socialization throughout a person’s life.1,2 Why is it such a powerful way to learn?

First of all, gaming is fun. Rose and Nichols, among others, have shown that the brain is most efficient when it’s enjoying an activity, and that activities that stimulate emotions as well as sensory input (such as shape, color, sound, and texture) are most effective at conveying information so that the brain retains it.3 The colors, stories, laughter, and excitement involved in gaming open your mind to what it can learn as you play.

Gaming also provides a means for people to repeat situations safely and easily so that they can try out different decisions to see if they work. By studying academic courses that were based on games, Knotts and Keys determined that people who honed their skills in games, by trying out different decisions and getting immediate feedback about whether they were good decisions, developed more valid and sound skills than those who learned by more abstract methods.4 By participating in the simulation-type situation that games provide, players also become actively involved with the information as they get into the game. This produces a “mindful” state in which people make more effort to think about what they’re doing and not to rely on automatic reactions, which helps anchor information in their minds. Information also becomes easier to integrate because it’s connected to a concrete situation and given a context, making it meaningful rather than inert.5

Playing games almost intrinsically encourages self-regulated learning, which is one of the most effective learning modes. Self-regulated learners are intrinsically motivated—they seek out learning experiences for their own value—and they participate actively in choosing and modifying the learning situation so that it best suits their needs.6 Because games are fun, we want to play them, and the learning and intellectual challenge are built in as part of the fun. Games also provide a wide selection of attractive learning situations, and choosing them for stimulation as well as fun allows players to provide themselves with the best learning situation.

Much research about games and learning focuses on children, but one body of research related to self-regulated learning provides an important and relevant framework for adult learning and its motivations: the Flow Theory of Optimal Experience developed by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.7 Flow theory gets its name from a particular state of extreme happiness and satisfaction produced by an activity. Flow occurs when people are so engaged and absorbed by an activity that they seem to “flow” along with it in a spontaneous and almost automatic manner, as if they are “carried by the flow” of the activity.

Flow comes from activities that provide enjoyment (as opposed to pleasure), which comes from one or more of the following factors:

Challenge is optimized; the activity is neither too hard nor too easy.

The activity absorbs all of the person’s attention.

The activity has clear goals.

The activity provides clear and consistent feedback about reaching the goals.

The activity is so absorbing that it frees the person from other worries and frustrations.

The person feels completely in control of the activity.

All feelings of self-consciousness disappear.

Time is transformed subjectively during the activity, passing without notice.

This could be a verbatim list of reasons that dedicated gamers might give you if you asked them why they play. Achieving flow state takes a certain amount of effort and dedication, but its rewards in psychological growth and happiness are great, and they’re only compounded by letting the pleasure of the flow state motivate you toward gaining the other intellectual benefits of gaming.

Finally, there is evidence that board games are among the mentally stimulating leisure activities that are associated with a lowered risk of dementia in aged people.8 While the correlation doesn’t prove a protective effect, gaming might have long-term benefits, which only adds a cherry on top of all the other positive effects.

In Real Life

As you might have guessed, I’m an avid board-game player myself. I generally play a minimum of one gaming session a week with my local group, and I often pick up a few games between meetings as well. I’ve played games since I was a child but have really only become deeply involved with them in the past five years or so. It has become such a rewarding and pleasurable experience for me, though, that I never intend to stop playing as much as I can.

One of my favorite games is Age of Renaissance. It’s a long and complex board game, which follows a group of European cultures through several historical eras. Along the way, each develops technologies, endures calamities and bad luck, acquires trade markets and resources, battles and makes deals with the other cultures, and tries to accumulate the highest point score as measured by cultural and technological advancements.

This game challenges just about as many skills as I can bring to the table with me; I often lose, but it’s so interesting and engaging that I’m still eager to play over and over. Playing Age of Renaissance has taught me how to build a long and complex strategy, how to use tactical moves to avoid sudden pitfalls and take advantage of good luck, how to negotiate wisely, how to assess probability and manage risk, and how to keep my focus on a goal instead of being distracted by side issues that might look interesting. I have taken every one of these skills and used it in other parts of my life, to my advantage.

Moreover, I have gotten an intuitive idea of how European culture developed and the cultural, economic, and geographical factors that influenced European history (and thereby the history of much of the world). I find now that when I am exposed to news about world politics, I have a very different view of its implications, which springs from my experiential knowledge of these historical simulations.

From other games, I’ve experienced more different simulated experiences than it would ever be possible for me to have in real life, and I’ve taken away something useful from almost all of them. I find new ways every day in which playing board games has improved my mind and changed my life for the better, and I can’t wait to see what new adventures I’ll have next week.

End Notes

Blanchard, K., and A. Cheska. 1985. The Anthropology of Sport: An Introduction. Bergin & Garvey Publisher, Inc.

Yawkey, T. D., and A. D. Pellegrini (Eds.). 1984. Child’s Play: Developmental and Applied. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rose, Colin, and Malcolm J. Nicholl. 1999. Accelerated Learning for the 21st Century. Dell Publishing.

Knotts, S. Ulysses, Jr., and J. Bernard Keys. 1997. “Teaching Strategic Management with a Business Game.” Simulation & Gaming, 28 (4): 337–393.

Salomon, G., D. N. Perkins, and T. Globerson. 1991. “Partners in cognition: Extending human intelligence with intelligent technologies.” Educational Researcher, 20(3): 2–9.

Zimmerman, B. 1990. “Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview.” Educational Psychologist, 25(1): 3–17.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1990. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

Verghese, J., R. Lipton, M. Katz, C. Hall, C. Derby, G. Kuslansky, A. Ambrose, M. Sliwinski, and H. Buschke. 2003. “Leisure Activities and the Risk of Dementia in the Elderly.” New England Journal of Medicine, 348: 2508–2516.

See Also

BoardGameGeek (http://www.boardgamegeek.com) is a tremendous repository for all things related to board games. Look up games by name and see reviews and supplemental information, chat with other gamers on bulletin boards, see lists of recommended games, and get news about new games, events, and awards. An essential reference.

Board Game Central (http://boardgamecentral.com) is another excellent source for board-game information. It’s particularly notable because it contains several lists of game award winners, such as the Spiel des Jahres winners.

Funagain Games (http://www.funagain.com) is one of the largest game retailers anywhere, and certainly the largest online. You can get almost any game you might want from the virtual shelves of Funagain and have it sent wherever you are. It’s also an excellent information resource; it has listings for the Games Magazine Games 100 winners for several years. (Each year, Games Magazine selects the 100 best games of the year and awards winners in several categories; this is one way to find good games to play.)

Marty Hale-Evans

Improve Visual Attention Through Video Games

Some of the constraints on how fast we can task-switch or observe simultaneously aren’t fixed. They can be trained by playing first-person-shooter video games.

Our visual processing abilities are by no means hardwired and fixed from birth. There are limits, but the brain’s nothing if not plastic. With practice, we can improve the attentional mechanisms that sort and edit visual information. One activity that requires you to practice lots of the skills involved in visual attention is playing video games.

So, what is the effect of playing lots of video games? Shawn Green and Daphne Bavelier from the University of Rochester, New York, have researched precisely this question; their results were published in the paper “Action Video Game Modifies Visual Attention,”1 available online at http://www.bcs.rochester.edu/people/daphne/visual.html#video.

Two of the effects they looked at are the attentional blink and subitizing. The attentional blink is that half-second recovery time required to spot a second target in a rapid-fire sequence. And subitizing is that alternative to counting for very low numbers (four and below), the almost instantaneous mechanism we have for telling how many items we can see. Training can both increase the subitization limit and shorten the attentional blink, meaning we’re able to simultaneously spot more of what we want to spot and do it faster, too.

Shortening the Attentional Blink

Comparing the attentional blink of people who have played video games for four days a week over six months against that of people who have barely played games at all finds that the games players have a shorter attentional blink.

The attentional blink comes about in trying to spot important items in a fast-changing sequence of random items. Essentially, it’s a recovery time. Let’s pretend there’s a video game in which, when someone pops up, you have to figure out whether they’re a good guy or a bad guy and respond appropriately. Most of the characters that pop up are good guys, it’s happening as fast as you can manage, and you’re responding almost automatically—then suddenly a bad one comes up. From working automatically, suddenly you have to lift the bad guy to conscious awareness so that you can dispatch him. The attentional blink says that the action of raising to awareness creates a half-second gap during which you’re less likely to notice another bad guy coming along.

Now obviously the attentional blink—this recovery time—is going to have an impact on your score if the second of two bad guys in quick succession is able to slip through your defenses and get a shot in. That’s a great incentive to somehow shorten your recovery time and return from “shoot bad guy” mode to “monitor for bad guys” mode as soon as possible.

Raising the Cap on Subitizing

Subitizing—the measure of how many objects you can quantify without having to count them—is a good way of gauging the capacity of visual attention. Whereas counting requires looking at each item individually and checking it off, subitizing takes in all items simultaneously. It requires being able to give a number of objects attention at the same time, and it’s not easy; that’s why the maximum is usually about four, although the exact cap measured in any particular experiment varies slightly depending on the setup and experimenter.

Green and Bavelier found the average maximum number of items their non-game-playing subjects could subitize before they had to start counting was 3.3. The number was significantly higher for games players: an average of 4.9—nearly 50% more.

Again, you can see the benefits of having a greater capacity for visual attention if you’re playing fast-moving video games. You need to be able to keep on top of whatever’s happening on the screen, even when (especially when) your attention is stretching.

How It Works

Given these differences in certain mental abilities between gamers and nongamers, we might suspect the involvement of other factors. Perhaps gamers are just people who have naturally higher attention capacities (not attention as in concentration, remember, but the ability to keep track of a larger number of objects on the screen) and have gravitated toward video games.

No, this isn’t the case. Green and Bavelier’s final experiment was to take two groups of people and have them play video games for an hour each day for 10 days.

The group that played the classic puzzle game Tetris had no improvement on subitizing and no shortened attentional blink. Despite the rapid motor control required and the spatial awareness implicit in Tetris, playing the game didn’t result in any improvement.

On the other hand, the group that played Medal of Honor: Allied Assault (Electronic Arts, 2002), an intense first-person shooter, could subitize to a higher number and recovered from the attentional blink faster. They had trained and improved both their visual attention capacity and their processing time in only 10 days.

In Real Life

Green and Bavelier’s results are significant because we continuously use processes like subitizing in the way we perceive the world. Even before perception reaches conscious attention, our attention is flickering about the world around us, assimilating information. It’s mundane, but when you look to see how many potatoes are in the cupboard, you’ll “just know” if the quantity fits under your subitization limit, and you’ll have to count them—using conscious awareness—if it doesn’t.

Consider the attentional blink, which is usually half a second (for the elderly, this can double). A lot can happen in that time, especially in this information-dense world: are we missing a friend walking by on the street, or cars on the road? These are the continuous perceptions we have of the world, perceptions that guide our actions. And the limits on these widely used abilities aren’t locked but are trainable by doing tasks that stretch those abilities: fast-paced computer games.

I’m reminded of Douglas Engelbart’s classic paper “Augmenting Human Intellect,”2 on his belief in the power of computers. He wrote this in 1962, way before the PC, and argued that it’s better to improve and facilitate the tiny things we do every day than it is to attempt to replace entire human jobs with monolithic machines. A novel-writing machine, if one were invented, just automates the process of writing novels, and it’s limited to novels. But making a small improvement to a pencil, for example, has a broad impact: any task that involves pencils is improved, whether it’s writing novels, newspapers, or sticky notes. The broad improvement brought about by this hypothetical better pencil is in our basic capabilities, not just in writing novels. Engelbart’s efforts were true to this: the computer mouse (his invention) heightened our capability to work with computers in a small, but pervasive, fashion.

Subitizing is like a pencil of conscious experience. Subitizing isn’t just responsible for our ability at a single task (like novel writing); it’s involved in our capabilities across the board, whenever we have to apply visual attention to more than a single item simultaneously. That we can improve such a fundamental capability, even just a little, is significant, especially since the way we make that improvement is by playing first-person-shooter video games. Building a better pencil is a big deal.

End Notes

Green, C. S., and D. Bavelier. 2003. “Action video game modifies visual attention.” Nature, 423: 534–537.

Engelbart, D. 1962. “Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework.”http://www.bootstrap.org/augdocs/friedewald030402/augmenting humanintellect/ahi62index.html.

Matt Webb and Tom Stafford

Don’t Neglect the Obvious: Sleep, Nutrition, and Exercise

You know as well as we do that you need to sleep well, eat right, and exercise for your brain to be in peak condition. We’re not going to scold you, but we are going to present some information you might not have known about your brain’s relationship to your body.

Many tips for mental performance concentrate on extending productivity for a short while after tiredness kicks in, or aiming for a slightly higher peak during a work period. Importantly, all of these increases in performance are relative to your normal or baseline level of functioning. You can often obtain more substantial and more widely effective gains in mental ability by making sure that your baseline performance is at an optimum. Tuning sleep, nutrition, and exercise is one effective way of doing this.

The brain, like any other organ in the body, works best when it is optimally fueled and is given adequate time to recover after periods of extended exertion or effort. Here, fuel does not mean energy in the form of only those foods that are broken down into glucose, but also those that provide essential nutrients needed for a wide range of complex functions. Neuroscience research has now identified a number of brain nutrients that can result in varying degrees of mental impairment if a deficiency exists.

On the other hand, sleep is still a bit of a mystery. Despite the fact that it takes up about a third of our time, we know surprisingly little about why we sleep. The nearest to a current consensus among scientists is that sleep, and particularly REM sleep, makes sense of disparate, emotionally fragmented, or weakly coupled memories and weaves them into a coherent structure that the brain can use more effectively during wakefulness. It is not clear, however, whether this theory is popular because memory is easy to test and so provides plenty of supporting evidence, or whether the function of sleep might be much broader, but evidence for the other functions has thus far been harder to come by. Either way, it is clear that lack of sleep causes a whole range of cognitive problems, suggesting that it fulfills an important role in maintaining the mind and brain at their peak.

Exercise is known to have beneficial effects on mental performance, both for the short-term oxygen boost it provides to the brain and for the important role that it plays in maintaining a healthy and efficient blood supply to the brain. The system of arteries and veins is important for providing essential nutrients and for removing dangerous toxins, and is so highly tuned that it can adjust in less than a second to take account of changing mental demands. This, however, requires an efficient, smoothly operating transport system (known as the cerebrovascular system), which is maintained and improved by regular exercise.

In Action

You can take some simple and practical steps with respect to sleep, nutrition, and exercise to improve your mental performance.

Sleep

A lack of sleep produces some of the most striking impairments in mental performance, as anyone who has pulled an all-nighter will know. A good night’s sleep [Hack #70] is particularly important for memory1, and there is now increasing evidence that things learned shortly before sleep are remembered better than those learned earlier in the day. It also seems that as something becomes more complex, the role of sleep is more important in efficiently remembering it. This applies equally to remembering skills involving body movements (for example, learning to juggle) and to remembering verbal or purely mental information.

The corollary of this—that sleep deprivation can negatively affect mental performance and muscle control—has been borne out by a number of studies that have shown that sleep deprivation can also result in mood disturbances.2 This suggests that skimping on sleep to give more time to learn can be counterproductive, as each hour spent sleep deprived is worth only a part of an hour fully rested.

One of the more surprising findings is that lack of sleep does not affect mental function only, but is related to a decrease in almost all measures of long-term health, including risk of heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and inflammation, to name but a few.3 These studies have led doctors to suggest that sleep should not be considered a luxury, but an important component of a healthy lifestyle, and therefore essential as a factor in maintaining cutting-edge brain function.

Nutrition

Following an all-around healthy diet ensures that an organ as sensitive as the brain has all the necessary resources available to work at an optimal level. Some nutrients and diet options have been particularly linked to maintaining a sharp mind. Some of the more unusual ones [Hack #73] are discussed in this book. Here, however, are some of the more well-known nutrients, although not everyone is aware of their importance.

Vitamin B12 and folic acid (also known as folate) are known to be important in mental performance.4 Adequate levels of these nutrients are vital, because they play a role in the functioning of the nervous system, including the creation of neurotransmitters (specifically dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine), as well as keeping levels of a risky amino acid, called homocysteine, to a minimum. High levels of homocysteine are now thought to be a major risk factor for poor health, with consequences including impaired brain function and possible damage to the heart, which can lead to a double whammy if the brain’s blood supply is affected.

Various fats are now known to affect how the brain works. A diet low in saturated fat and high in cereal and vegetable foods is known to promote good cognitive function, as is a diet high in certain omega-3 fatty acids, which are present in flax seed, walnuts, and oily fish.5 These fatty acids are now thought to be so important that omega-3 supplements are now being tested as effective ways of improving mood and cognition in certain types of mental illness.

Antioxidants prevent the oxidation of other chemicals, a process known to produce tissue-damaging substances called free radicals. Several essential nutrients are antioxidants, including vitamins A, C, and E, and the trace element selenium (present in Brazil nuts). Low levels of antioxidants have been linked to an increased risk for a number of brain disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, but it is not clear whether there is a link to mental function in healthy young people. It does seem, however, that a good intake of these nutrients may protect against cognitive decline in later life.6

Breakfast is often called the most important meal of the day, and there is some evidence to support this claim. Missing breakfast has been consistently linked to poor mental performance, particularly on memory and visual recognition tasks,7 at least in children, on whom most of this research has been carried out. There is some evidence that high-fiber foods that release energy slowly (such as some cereals) and high-protein foods may be particularly good for keeping your edge throughout the morning, and low-fiber, high-carbohydrate foods (such as pastries) might cause a period of slower, fuzzier thinking.

Exercise

Walking for 30 minutes a day five days a week is typically recommended as adequate exercise for significantly improving all-around health. It has the medium- to long-term effect of strengthening the heart, reducing blood pressure, and even lifting mood. All of this is good news for sharpening the mind, which does better with a healthy brain and positive outlook. In the short term, any activity that boosts oxygen intake will immediately affect mental performance for the better,8 so as long as it is not too distracting, any light exercise should help you learn while you take part.

In Real Life

The link between brain function and sleep, nutrition, and exercise is still only partially understood, so the recommendations for healthy daily amounts change over time as new research emerges. Keep up with the latest in health advice to make sure you can tune your life for optimal brain function.

One consistent finding is that middle-aged and older adults tend to show a greater detriment in mental function due to poor diet, sleep patterns, and exercise than younger adults do. If you are middle-aged or older, paying particular attention to these health issues will ensure you keep your edge well into old age. If not, there’s no time like the present to establish healthy habits that will bring you benefits for the rest of your life.

End Notes

Stickgold, R., J.A. Hobson, R. Fosse, and M. Fosse. 2001. “Sleep, learning, and dreams: off-line memory reprocessing.” Science, 294: 1052–1057.

Durmer, J.S., and D.F. Dinges. 2005. “Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation.” Seminars in Neurology, 25: 117–129.

Alvarez, G.G., and N.T. Ayas. 2004. “The impact of daily sleep duration on health: a review of the literature.” Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing, 19: 56–59.

Stabler, S. 2003. “Vitamins, homocysteine, and cognition.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78: 359–360. http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/content/full/78/3/359.

Kalmijn, S., M.P. van Boxtel, M. Ocke, W.M. Verschuren, D. Kromhout, and L.J. Launer. 2004. “Dietary intake of fatty acids and fish in relation to cognitive performance at middle age.” Neurology, 62: 275–280.

Gray, S.L., J.T. Hanlon, L.R. Landerman, M. Artz, K.E. Schmader, and G.G. Fillenbaum. 2003. “Is antioxidant use protective of cognitive function in the community-dwelling elderly?” The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 1: 3–10.

Rampersaud, G.C., M.A. Pereira, B.L. Girard, J. Adams, and J.D. Metzl. 2005. “Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105: 743–760.

Scholey, A. 2001. “Fuel for thought.” The Psychologist, 14: 196–201. http://www.bps.org.uk/_publicationfiles/thepsychologist%5CScholey.pdf.

Get a Good Night’s Sleep

By programming the associations your brain makes as you start to feel sleepy, you can set yourself up for a good night’s sleep—or an awful one.

Here’s the straight dope about getting a good night’s sleep. There’s no miracle method here, no secret that will let you survive and thrive on less than four hours a night. But hopefully, you should be able to make sure that you spend more of the time you allocate to sleeping actually asleep, and spend less of the time you want to be awake sleepy.

Everybody has slightly different preferences about when and how they sleep. The idea of morning people and evening people is solid fact, not myth.1 People also vary in how much sleep they need, and how they feel when they don’t get it. We don’t need to be macho about it. If you need nine hours a night, that’s normal; don’t starve yourself. Many of the people who supposedly need very little sleep are nappers, such as Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher, two British prime ministers who famously got by on four hours a night or less. Others kept up sparse sleep habits for short periods only when they had big projects going, such as Leonardo da Vinci, who reported that he’d sleep for 15 minutes every four hours.2

Too little sleep is bad for your health and it will make you feel rotten, even if you are awake. That said, too much sleep is bad for you as well.3 The average is seven to eight hours a night, with variation among individuals about how much and exactly when they want to take it. This hack is about quality and efficiency of sleep, about making sure that when you want to be asleep you are, and that when you do sleep it’s good sleep.

Tip

Sleep is nourishment for your mental life. Although my guess is that we’ve evolved to want more sleep than we really need (as with food), and we all can certainly get by for a few nights with very little sleep, trying to establish a long-term routine that deprives you of sleep will harm your mood, your memory, and your performance during the day. Plus, you’ll be missing out on one of life’s great pleasures. So, beyond a wholesome discipline, I recommend being gentle on yourself.

Sleep Hygiene

Really, this is a story about associations. Your brain constantly scans the environment and puts things together in memory. Mental connections are made between things that occur at the same time, or in the same place, or that are followed by good or bad consequences. Continuously, often unconsciously, your brain is associating.4 We can use this to help get a better night’s sleep and to understand some of the bad sleep habits that you might have fallen into.

The key idea here is sleep hygiene, which means keeping those things you associate with sleep totally separate from those things you associate with being awake. We’ll assume that, being a sensible person, you already do all the obvious things that will help you sleep. As a reminder, some of those are:

- Making a comfortable bed

Create for yourself whatever a comfortable bed means to you, hard or soft, big or small, in whatever location you find most relaxing.

- Being able to keep warm or cool all night

Provide yourself with your favorite blankets, fans, or whatever you need.

- Being somewhere quiet

If your room isn’t quiet enough, lots of people swear by earplugs or white-noise machines.

- Being somewhere dark

Likewise, lots of people swear by eye masks and blackout curtains when they can’t find a dark room.

- Being well nourished, but not eating heavily immediately before sleep

Especially be sure to get enough iron, lack of which can cause daytime fatigue.

- Cutting out caffeine at least eight hours before bed, and not drinking alcohol

Both of these drugs will reduce the quality of sleep you get, even if they don’t reduce the quantity.

Making Associations

So, if your sleep isn’t being artificially affected, and the physical conditions are ripe for a good night’s sleep, the best way to ensure that you get it is to strongly associate when and where you sleep with sleep, and sleep only. You train the associations by your behavior, so your brain picks up the regularities in your experience and ingrains them as habit. Three kinds of associations to think about are those relating to object and location, time, and behavior.

Object and location

Associations in object and location means, simply, that you should use your bed, and the other things around you when you sleep (e.g., nightwear), purely for sleep and nothing else.5 If you wander around in your pajamas in the morning for hours, or sit in bed and read till the small hours (or worse, use a laptop), you’re sending a confusing signal to your brain. “Is this sleep time?” your brain will be asking, “or is it awake time?”

When you get into bed, go to sleep; when you wake up, get out of bed immediately and get changed. If you can’t sleep for 20 minutes, get up and be awake somewhere else. You need to preserve the association of your bed with being asleep, not with trying to get to sleep and worrying about it. This is why study-bedrooms are such a disaster. When you are working, you look at your bed and feel sleepy. When you are trying to sleep, you look at your work and think about work.

Time

Setting aside dedicated space is a good method for any activity that requires a certain frame of mind, not just sleep. Even better is if you can set aside dedicated space and regular dedicated time. Regular time is particularly important if you can’t schedule dedicated space, and vice versa.

A regular bedtime works well for children, but most of us don’t have the lifestyle that permits going to bed at the same time every night, even if we know that this habit would help us sleep better. One thing that works well for many people is to have a fixed wake-up time and being flexible with going to bed.6 This gives you the routine that will train your body to wake up and be awake in the morning, but also the flexibility that lets you go to bed when you are actually tired, rather than when you think you should be.

After a while of doing this, your body will learn to wake you up in the morning, and because your body clock is expecting that fixed waking-up time, it will learn to make you feel tired at an appropriate time the evening before (with accommodation for seasonal variations in sleep requirements, and other personal fluctuations that happen more or less at random). And if you ever do need to stay up late (work? babies? friends who are incorrigible evening people?), you are not breaking the association of your wake-up time with being awake, and the routine you’ve established should carry you through any extra bit of tiredness you incur.

Behavior

The third kind of associative purity is associations between what you do and sleep. Although some of us don’t need any cues to just drop off, most of us need to wind down a bit before we slip away into the land of dreams. If you establish a fixed ritual before you go to bed, it will tell all the unconscious and semiconscious parts of your mind clearly that now it is time to sleep. It doesn’t have to be a long list; maybe just perform your ablutions, change into whatever you wear at night, turn off the light, and then hit the pillow. The important thing is that whatever you do, you don’t do any of these things long before you go to bed, or do them out of order, or mix in anything not sleep related. For example, getting into your pajamas and then doing 30 minutes on the StairMaster is a recipe for troubled sleep in the future.

Likewise, when your alarm goes off in the morning, get up immediately and change clothes. If you’re having particular trouble training yourself in a getting-up habit, you might try incorporating some morning physical exercise, a particularly un-sleeplike association to develop. If you have trouble getting to sleep, you might want to put something in your pre-bed routine to make it longer, preferably something you can do until you are properly ready to go to bed. Something like reading is ideal, because it is gentle and it is an enjoyable way to wait until you are sleepy.

Structure versus flexibility

Setting up and maintaining pure associations between sleeping time and awake time should help you be asleep when you want, and wake up when you want as well. The cost is a loss of flexibility, but the benefit is spending less time trying to sleep and not being able to.

The structure provided by routine should carry you through times when tiredness might otherwise make you fall asleep. You might decide that you value the flexibility of being able to break all these associations more than the benefits of creating and maintaining them. This is great, if it works for you. And there’s some good evidence that when it comes to sleep, whatever you do, it is vital not to take things too seriously and that worrying may be the worst thing of all.

Hacking the Hack

Our perception of time is radically distorted when we are asleep or close to sleep.7 By attaching electronic monitors to insomniacs, it is possible to show that many who report sleeping only two or three hours a night are actually asleep for an average of seven hours—only 35 minutes less than the average for non-insomniacs! So, for insomniacs, or the rest of us on a bad night, when we feel like we “hardly slept at all,” we were probably asleep for most of the night but only remember vividly, and exaggerate, the time when we were trying to get to sleep. Not only this, but if you tell insomniacs that they actually slept better than they did, they then feel and perform better during the day.8

Other results show that it is impossible to prove an extra effect of broken sleep beyond the amount of sleep time you lose from being awake.9 In other words, if a screaming baby wakes you up in the middle of the night for 20 minutes, there’s no reason that this should make you feel any worse in the morning than going to bed 20 minutes later than normal would have. Any discontent you do feel is probably due to stress, rather than lack of sleep per se.

This means that it’s how you feel about how much sleep you got, as well as how much sleep you actually got, that matters. If you can avoid worrying about it, avoid watching the clock and counting the hours, that’s as useful as actually getting a few more minutes. Obviously, most insomniacs don’t want to worry about not getting enough sleep, so does knowing this help? Well, hopefully it helps a little bit. When you think you haven’t slept enough, you probably have. As long as you cover a core minimum of sleep, which is probably a couple of hours less than you normally get, you might feel tired but your performance won’t suffer. If you know that awakening in the middle doesn’t have to matter that much, you are free not to worry excessively about how much sleep you get. And the beautiful thing is that if you don’t worry about it, you’ll sleep better and you truly will require less sleep overall.

End Notes

This post is a highly recommended place to start finding out about the science of sleep, including the details of larks and owls: “Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sleep (But Were Too Afraid To Ask).” http://circadiana.blogspot.com/2005/01/everything-you-always-wanted-to-know.html.

This kind of thing isn’t sustainable over the long term, and would be a nightmare for everyone you knew anyway.

Kripke, D., et al. 2002. Mortality Associated With Sleep Duration and Insomnia. The Archives of General Psychiatry, 59: 131–136. Also, see “Too much sleep ‘is bad for you',” at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/1820996.stm, which notes, “A study that included more than a million participants found people who sleep eight hours or more died younger.” (Although this is just an average, what counts as too much or too little depends on your individual requirement.)

This power of association is called conditioning in psychology. I wrote a bit more about it in Mind Hacks, where I talked about how caffeine, because it is a drug of reward, can rewire our brains to make us obsessive about how our coffee is prepared and served. A PDF of the draft hack is available from the O’Reilly page for the book, at http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/mindhks/chapter/hack92.pdf.

Well, maybe for one other thing!

See Steve Pavlina’s “How to Become an Early Riser” at http://www.stevepavlina.com/blog/2005/05/how-to-become-an-early-riser for a great piece discussing how the author turned himself from an evening person to a successful morning person using the fixed-rising-time method.

Semler, C.N., and A.G. Harvey. 2005. “Misperception of sleep can adversely affect daytime functioning in insomnia.” Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43: 843–856. Also, see “You’re feeling very sleepy” at http://bps-research-digest.blogspot.com/2005/05/youre-feeling-very-sleepy.html.

Tang, N.K.Y., and A.G. Harvey. 2004. “Correcting distorted perception of sleep in insomnia: a novel behavioural experiment?” Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42: 27–39. Also, see “Don’t think, sleep!” at http://www.mindhacks.com/blog/2004/12/dont_think_sleep.html.

Wesensten, N.J., et al. 1999. “Does sleep fragmentation impact recuperation? A review and reanalysis.” Journal of Sleep Research, 8: 237–245.

Tom Stafford

Navigate Around the Post-Lunch Dip

Recognize the differences in your state of mind at different times of the day.

One function of your biological clock is to adjust your level of wakefulness during the day. As a general rule, concentration and logical reasoning peak between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m., and alertness peaks between 4 p.m. and 8 p.m. A sleepy feeling in the early afternoon known as the post-lunch dip is common. A large lunch with alcoholic drinks will clearly contribute to the effect, but the effect is present even without it.

These patterns aren’t the only diurnal fluctuations in awareness, which vary from person to person. Mapping your own variation in mindset over the course of the day will allow you to plan accordingly. The intention is to use the pattern to your advantage, instead of trying to maintain some optimal state.

In Action

People vary a great deal in their chronotype: the way specific times of day affect them. As a rule, older people tend to be morning types and younger people more alert in the early evening, but this is only a general trend. However, the post-lunch dip, a low point of wakefulness in the circadian rhythm that coincides with the process of body chemistry switching to digestion after a meal, is something many people experience.

Here are a few suggestions for dealing with the post-lunch dip:

Experiment with changes in what you eat for lunch. Try reducing the amount of carbohydrate-rich food, as well as increasing the variety and reducing the quantity of your food. Although my colleagues find it a bit odd, I find mugs of hot water through the day help me stay sharper, especially for the hour or so after lunch. Tastes and food sensitivities vary, so try making changes and see what works for you. One tip: the duration of effects of food varies, and the intensity of these general tendencies will vary from person to person. Sugars (in large quantity) have rapid onset, but their effects tail off quite quickly. Hydrogenated oils have a slower onset, and their influence can last for hours.

Tip

You can use the rapid onset of sugar’s effects [Hack #72] to enhance learning.

Have lunch right at the start of your lunch break, and then spend the remainder of the break taking a walk. Less of your post-lunch dip happens while you’re trying to work after lunch, and the exercise helps wake you up and walk off stress. It also speeds the digestion process and can improve your body’s uptake of glucose from the blood, which may shorten the rebound time after eating.

Lastly, adjust the timing of specific tasks so that you work with your mindset. Choose tasks for after lunch that need to be done, but that don’t require especially intense thought. Active tidying-up tasks are a good choice.

How It Works

Taking time to learn how the mind changes during the day allows one to plan for it. The simple act of taking a walk at lunchtime can have much more benefit to thought than it might seem. It is quite effective in reducing work-related stress. Unloading such stress has a positive effect on clarity of thought. The post-lunch dip is an almost ideal time for unwinding. It’s a time of naturally reduced alertness, so it becomes easier to shake off stress than when the body is on alert.

Scheduling tidying-up tasks for after lunch works for similar reasons. Because the tasks aren’t highly demanding of attention, the mind can tidy itself in the background at the same time, making it easier for the tidied mind to be more efficient an hour later.

In Real Life

The variation in mindset within a day also suggests why writers should find a writing routine that suits them, a standard time of day during which to write. I’ve been part of an amateur fiction writers’ group for many years. One problem I’ve often had was picking up a story I’d partly written earlier and continuing it in another session. I’d find the pieces “didn’t join up” at the point where I’d put down the writing and then picked it up again. I was writing in a different mood when I started again.

A factor in this became clearer when, for a couple of months, I started waking early and writing for an hour each morning. My hope was that by writing just after waking, I would be more creative than normal. I found that when I wrote this way I had no problem with the pieces joining up. Unfortunately, at that time in the morning, my style of writing was too surreal and whimsical. It was consistent, but not in a way that I wanted. Although the experiment didn’t work the way I had hoped, it showed me that the principle is valid: mindset changes during the day.

Overclock Your Brain

In some situations, the brain is performance-limited by the available fuel. Increase the fuel and you can temporarily get a performance boost.

The brain is one of the most energy-hungry of the human organs. Despite making up only about 2% of the average body weight, it uses almost 20% of the normal intake of energy. Although the brain comprises mostly fat, this is mainly used to protect and insulate brain cells and is not available as an energy store. It therefore relies on the rest of the body to provide it with a supply of energy, which consists almost entirely of glucose. The brain uses up its own glucose supplies in about 5–10 minutes if they are not replenished, meaning it is particularly sensitive to changes in blood glucose levels.

As part of this process, oxygen is also needed and is another essential component of the brain’s fuel supply. Oxygen is used as part of glucose metabolism to provide brain cells with a number of important chemicals that allow them to support themselves and communicate with other neurons.

Mental performance relies on the functioning of the brain, and like with any other organ, this performance is linked to how many resources are available. Research has shown that in some instances, mental performance is rate-limited by the available glucose and oxygen. In other words, you can increase the rate of mental processing by increasing the available fuel.

It turns out that this effect is not global, and it typically affects some mental abilities more than others. To get the best performance increase, you need to know how quickly glucose and oxygen are metabolized in the body to perfect your timing, and which mental processes are most affected to select your task.

In Action

One of the most reliable findings is that increasing available glucose and oxygen seems to have a beneficial effect on memory. Importantly, the effect is usually found for memory encoding but not memory recall. If you are not familiar with this distinction, think of it in terms of the mental activities involved in memory. Encoding is when you encounter the information and try to commit it to memory, and recall is when you want to retrieve previously committed information.

Increasing glucose and oxygen supplies to the brain seems to allow information to be committed more accurately and fully to memory; in other words, you learn better. This means when you come to recall it at a later stage, you will undoubtedly do better, because the information there is clearer and more comprehensive. The reverse does not seem to be true, however. If you first encoded something without the aid of extra oxygen and glucose, suddenly making more oxygen and glucose available when you try to recall it will not improve your overall memory performance.

Boost oxygen levels

The improvement in oxygen levels on memory1 typically lasts for a few minutes only (five is about the limit), so you need to time your learning to happen shortly after an increase in oxygen, or ensure that you maintain a slightly increased level for the duration of the learning period. Oxygen canisters are available in some shops, although they are often expensive and unwieldy. More usefully, deliberately taking some deep breaths will increase blood oxygen levels for a short time, as will light exercise. Going for a walk while listening to something you want to remember on an MP3 player should do the trick, as long as the environment is not so distracting that you cannot concentrate.

Optimize glucose supplies

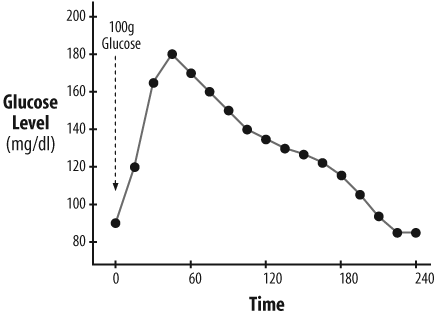

Glucose has a much longer-term effect, as shown in Figure 8-1.2 Here the maximum available glucose peaks at about an hour, although it rapidly becomes available after it has been ingested. All energy-giving foods are broken down into glucose at some stage, although at different rates. This graph charts the rate of pure glucose absorption, so it best matches the effects of sugary drinks.

Glucose is important as a simple fuel, but it is also used in the creation of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. This brain chemical is particularly linked to memory, and it’s no accident that, like oxygen, extra glucose is linked to an increase in memory and learning ability.3 Again, timing is crucial, but not so much effort is needed to constantly maintain glucose levels. A well-timed sugary drink, 30 minutes to an hour before you want to remember or take notice of something particularly closely, should improve how well you remember it.

End Notes

Scholey, A.B., M.C. Moss, and K. Wesnes. 1998. “Oxygen and cognitive performance: the temporal relationship between hyperoxia and enhanced memory.” Psychopharmacology, 140: 123–126.

Messier, C. 2004. “Glucose improvement of memory: a review.” European Journal of Pharmacology, 490 (1-3): 33–57. Figure 8-1 is my own simplified re-creation of a graph from this article.

Meikle, A., L.M. Riby, and B. Stollery. 2004. “The impact of glucose ingestion and gluco-regulatory control on cognitive performance: a comparison of younger and middle-aged adults.” Human Psychopharmacology, 19 (8): 523–535.

See Also

“Fuel for thought” by Andrew Scholey. http://www.bps.org.uk/_publicationfiles/thepsychologist%5CScholey.pdf.

Vaughan Bell

Learn the Facts About Cognitive Enhancers

“Smart drugs” are supposed to make you smart, but it’s not always smart to take them. Until smart drugs are safer and more effective, there are some alternative mental-performance enhancers to try that are both interesting and legal.

Mind-altering substances have been used for millennia to alter how we perceive and understand the world. Some of these substances have been taken because they are thought to enhance specific aspects of our thought and behavior to enable us to become more productive—caffeine is a popular example.

More recently, advances in drug testing and development and a better understanding of how the brain works have resulted in drugs that are intended to boost intelligence or cognition in specific ways. Often, these drugs have been developed to help with specific illnesses or conditions, but they are now gaining notoriety, as they are being used illegally by people hoping to improve performance during intense work or study periods. Others are still in development and are currently only in the experimental stages:

- Pharmaceutical amphetamines (such as Adderall and Ritalin)

These drugs have been used without a prescription, for their tiredness-reducing and concentration-enhancing effects, by about 5% of students in U.S. colleges, according to a recent study, with some colleges reporting rates as high as 25%.1

- Modafinil

Modafinil is a nonamphetamine stimulant, marketed to help people with narcolepsy stay awake. It has been reported as popular with otherwise healthy individuals who are using it to maintain concentration levels and alertness during several days of wakefulness.2

- Ampakines

Ampakines are a class of drugs known to affect the sensitivity of the brain to a neurotransmitter called glutamate, a chemical known to be important in fast information transfer and memory formation. These drugs are still in development, but one, known as CX516 and currently targeted at treating schizophrenia, has been shown to improve cognitive performance in the elderly3, and other ampakines, such as CX717, are being touted as future cognition-enhancing drugs.

- MEM 1003

MEM 1003 is a substance being developed by a company advised by the Nobel Prize–winning neuroscientist Eric Kandel. Although few details are available, it is to be marketed for clinically diagnosable conditions, but also for “age-associated cognitive decline” in healthy individuals. In other words, it’s a chemical pick-me-up for those experiencing the normal decline in memory that typically occurs past middle age. The fact that this drug is being openly promoted for use in people without serious illness suggests that cognitive enhancers may become increasingly mainstream.

Most of these drugs are still in the pipeline, and for the time being most “cognitive enhancers” are officially classed as medicines. Nonmedical uses of these substances are officially frowned upon, and possession could lead to jail time in some countries. For some people, however, a greater risk may be unwanted short- or long-term effects of such drugs. It is well known that amphetamines can trigger psychosis in some users, particularly with heavy use, and the fact that most people will use them without proper medical advice and assessment makes it unlikely that any negative effects will be detected sufficiently early. Newer drugs are typically marketed as being free of side effects, although history tells us that some side effects do not come to light until later on.

For those wanting to avoid pharmaceuticals, the scientific literature has reported some alternative ways of temporarily boosting mental performance, some more unusual than others.

In Action

Some foods and over-the-counter drugs may significantly enhance your mental performance, if taken in moderation.

Glucose

Glucose is the brain’s fuel, and there is plenty of evidence that a well-timed glucose intake increases mental performance and that you can use sugary drinks to overclock your brain [Hack #72]. Glucose is broken down to become an important element in brain-cell function, as well as being important in the creation of a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine. This chemical is particularly linked to memory, and it is no accident that extra glucose is linked to an increase in memory and learning ability.4 In the long term, too much sugar can lead to health problems, but in the short term it can give a brief mental lift.

Ginkgo biloba

Gingko biloba is an ancient plant that has survived many thousands of years and has no living relatives. It’s commonly sold in health-food stores as an herbal supplement, and there is good evidence that in small doses it can increase mental performance, particularly attention, in healthy young adults.5 It is thought to work through direct effects on neurotransmitters and by promoting blood flow and circulation to the brain. Although ginkgo is considered safe enough to be sold in shops, it does not agree with everyone. Some people may find it upsets their stomach. More seriously, it can act as a blood thinner, and it’s usually advised that people with blood circulation disorders, those taking aspirin, pregnant women, and people taking certain forms of antidepressants (known as monoamine oxidase inhibitors or MAOIs) should avoid it as a precaution. If in doubt, discuss it with your doctor.

Chewing gum

Chewing gum? A number of recent studies have found that chewing gum improves mental performance, typically memory.6 It’s still not clear exactly why this happens. Speculations include the fact that chewing causes insulin to be released in the body in anticipation of food digestion, which increases the rate of glucose uptake. This might make more glucose available for the brain, temporarily providing more fuel for cognitive functions. Another theory is simply that chewing increases arousal, making us slightly more alert and therefore that little bit sharper.

Tyrosine

Tyrosine, an amino acid, is one of the building blocks of a group of neurotransmitters called the catecholamines, which include dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. It’s commonly available as a supplement in health-food shops and has been shown to significantly increase mental performance, particularly during periods of tiredness.7 In some people, however, it can trigger migraines and stomach upset, and people taking antidepressants and stimulants are usually advised to avoid it to prevent potentially harmful interactions.

Ginseng

Ginseng is a plant extract that is taken throughout the world, and a number of claims have been made for ginseng’s brain-boosting properties. Nevertheless, controlled studies have shown mixed results,8 suggesting that it may increase memory performance, although this can be accompanied by a decrease in attention. Serious problems can occur from taking too much ginseng, since it has effects involving the adrenocortical hormones. It’s best taken with care, or under the supervision of an experienced medical practitioner, and despite its popularity, the scientific jury is still out on this ancient supplement.

In Real Life

Education and information are the key to the safe and smooth running of your brain. Make sure you are fully informed about the things you put into your body and how they affect your thoughts and behavior, whether they come from multimillion-dollar drug companies or the local grocer. Also, don’t overlook the everyday maintenance [Hack #69] of your body that can keep your mind optimally tuned.

End Notes

McCabe, S.E., J.R. Knight, C.J. Teter, and H. Wechsler. 2005. “Non-medical use of prescription stimulants among U.S. college students: prevalence and correlates from a national survey.” Addiction, 100 (1): 96–106.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A61282-2002Jun16? language=printer.

Johnson, S.A., and V.F. Simmon. 2002. “Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled international clinical trial of the ampakine CX516 in elderly participants with mild cognitive impairment: a progress report.” Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, 19 (1-2): 197–200.

Meikle, A., L.M. Riby, and B. Stollery. 2004. “The impact of glucose ingestion and gluco-regulatory control on cognitive performance: a comparison of younger and middle-aged adults.” Human Psychopharmacology, 19 (8): 523–535.

Kennedy, D.O., A.B. Scholey, and K. Wesnes. 2000. “The dose-dependent cognitive effects of acute administration of ginkgo biloba to healthy young volunteers.” Psychopharmacology, 151: 416–423.

Scholey, A. 2004. “Chewing gum and cognitive performance: a case of a functional food with function but no food?” Appetite, 43: 215–216.

Magill, R.A., W.F. Waters, G.A. Bray, J. Volaufova, S.R. Smith, H.R. Lieberman, N. McNevin, and D.H. Ryan. 2003. “Effects of tyrosine, phentermine, caffeine D-amphetamine, and placebo on cognitive and motor performance deficits during sleep deprivation.” Nutritional Neur oscience, 6 (4): 237–246.

Vogler, B.K., M.H. Pittler, and E. Ernst. 1999. “The efficacy of ginseng. A systematic review of randomised clinical trials.” European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 55 (8): 567–575.

Vaughan Bell

Snap Yourself to Attention

Change your behavior by rewarding your hard work and punishing your slacking off.

As a self-aware animal, you can motivate yourself with the techniques of animal training. You can increase the number of your accomplishments by defining measurable units of achievement, breaking down your project into those units, and then giving yourself either a fixed reward per accomplishment or a fixed negative punishment for each lapse—or both, if you prefer.

First, a word about definitions. Behaviorist and animal trainer Karen Pryor has a concise, classic definition of a behavioral reinforcer:1

A reinforcer is anything that, occurring in conjunction with an act, tends to increase the probability that the act will occur again.

Technically, punishment is not a reinforcer, since it decreases the likelihood an action will occur. (Of course, sometimes that’s what you want.) We won’t go into the intricacies of the behaviorist definitions of positive and negative reinforcement, which probably don’t mean what you think they do.2 There is even debate among behaviorists whether self-administered reinforcement, as in this hack, is a coherent concept or is better defined as something like “self-monitoring.”3 For the purposes of this hack, we’ll just stick with the commonsense definitions of reward and punishment most people already have.

In Action

Break down your task into accomplishment units. If you’re a Getting Things Done 4 fan, you can define these units as being the size of a next action, which is a single task of a few minutes or less that you can easily do to further a project.

When you accomplish one of these task subunits, reward yourself. Here are a few examples of rewards you can give yourself, paired with typical accomplishments you might want to reward:

Surfing the Web for half an hour after writing five pages of your paper

Having a piece of cake after studying 20 pages of your astronomy textbook

Socializing for an hour after cleaning three rooms of your house

If you fail to accomplish one of the units of accomplishment, or exhibit some unwanted behavior, you can punish yourself, although you might find a reward-only system to be effective as well.

Here are a few examples of punishments you can give yourself, paired with typical unwanted behaviors:

It’s important to keep your reward or punishment immediate, consistent,6 and proportionate. Snapping a rubber band every time you bite your nails is OK, but burning a $20 bill every time you do so is probably excessive.

Rewards (such as candy or a kiss) are usually preferable to punishment (such as an electric shock), not only because they’re more ethical, but also because they’re more effective.7 However, since you’ll be rewarding and punishing yourself in this hack, and you presumably know how much is excessive, you can use any combination that works for you.

You might need to experiment to hit the effective zone between excessive punishment or reward, and punishment or reward that’s too weak to be motivational. A good place to start is to monitor your anticipatory feelings: do you look forward to your self-administered reward or cringe at a possible punishment? Do you feel motivated to get on with your task? If your punishment is excessive, you might just give up, so don’t be too hard on yourself.

Excessiveness is only one of the problems that can occur if you’re attempting to change someone else’s behavior. If the subject isn’t human, she might also misunderstand which behavior you’re trying to change. However, when you’re working with yourself, the problem of conveying the reason for the reward or punishment is lessened. As you eat your slice of cake, or hang out with your friends at the coffee house, reflect on your accomplishment to connect your behavior with the way you hacked it.

In Real Life

If you find the carrot and stick aren’t working, maybe they’re not big enough, or maybe you’re not applying them consistently enough. Ask your friends to catch you in the act. They might really enjoy watching you snap yourself with a rubber band or burn a $20 bill. They might also have good ideas about what punishments and rewards you can use; it can be even more fun to solve this kind of problem for someone else.

As far as carrots go, my wife Marty and I are comedy junkies, so every time we finished writing and editing a hack for this book, we allowed ourselves a half-hour of video comedy. (For this reward, it helps to have a TiVo and access to some large video collections.)