Chapter 3

Applying Mindfulness in the Workplace

In This Chapter

![]() Dealing with uncertainty

Dealing with uncertainty

![]() Changing your mindset

Changing your mindset

![]() Discovering that you can rewire your brain

Discovering that you can rewire your brain

![]() Considering ethics in the workplace

Considering ethics in the workplace

Mindfulness is all well and good, but how do you apply it effectively in the workplace? That’s exactly what you find out in this chapter. You also discover why mindfulness is more important than ever in the modern workplace and discover lots of practical ways to start ‘mindfulnessing’ within minutes!

Gaining Perspective in the Modern-Day Workplace

Fifty years ago, a sizeable proportion of the population got a job and worked for that organisation until they retired. The key benefit resulting from this scenario was a sense of security and stability – you knew what to expect.

For students looking for a job today, things are very different. A recent survey of workers found that one in three remains in a job for less than two years. This massive change in people’s working lives is bound to have an impact – sometimes positive, but often negative. In this section, you discover how mindfulness can help you deal with uncertainty in the workplace.

Engaging with a VUCA world

To understand the modern workplace and how mindfulness can help you deal with it, consider an acronym – VUCA. Originally used by the military, VUCA is now used in business.

VUCA stands for:

- Volatility: The high speed and complicated dynamics of change in modern organisations and the markets that they work in. The digital revolution, global competition and connectivity are all contributing to higher levels of volatility.

- Uncertainty: The lack of predictability and prospect of surprise facing many employees. In uncertain situations, forecasting becomes difficult and decision making becomes more challenging.

- Complexity: The wide range of ideas, information and systems that cause confusion and chaos in an organisation leads to complexity.

- Ambiguity: The lack of clarity about what is actually happening within the organisation as well as the environment in which the organisation operates.

To give you an idea of the VUCA world, consider the average working day of Kate, a senior executive. Her alarm goes off at 5 a.m. She turns on her phone as she wakes up and it immediately starts buzzing. She skims through and half answers emails as she gets dressed, has a quick cup of coffee and piece of toast. She jumps into her car and mentally compiles a to-do list on the journey. Half of the emails she read earlier appear urgent, so she wants to deal with them immediately. However, the complexity of the issues makes it almost impossible for her to decide which one to do first. Juggling between phone calls, emails, routine tasks and meetings, she definitely has no time for lunch. She works till late into the evening, keeping herself going with lots of cups of coffee. To ensure that she remains awake for the journey home, she blasts out music on her iPod. As she travels, her phone keeps buzzing with more emails. Kate grabs a takeaway, eats it in front of the television and then goes to bed. She answers a few more emails before turning off the light and then tries to sleep. Unsurprisingly, sleep eludes her as she tosses and turns, going over everything that’s happened during the day and worrying about how she’s going to function the next day if she doesn’t get to sleep soon.

Kate’s working day is certainly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous. How can mindfulness help her? Below are a few changes that she can make to her day, that take up almost no time at all and that increase her effectiveness and efficiency:

- Over breakfast, Kate can keep her phone switched off and eat her toast being mindfully aware of its taste, perhaps looking out into her garden as she does so. The meal would be finished a bit quicker (because she isn’t simultaneously dealing with emails) and the time saved can be used to check emails later in the office.

- She can take three mindful breaths before setting off in her car. Driving with mindful awareness, focusing solely on the road ahead rather than mentally planning her day, means that her mind is rested and ready for work.

- Arriving at the office, she can again take a few deep mindful breaths, instantly calming her fight-or-flight mechanism even if she’s had a difficult journey.

- As she waits for her computer to start up, she can enjoy a mindful stretch in her chair. She can then organise her priorities for the day rather than allow her attention to be captured immediately by emails.

- She can allot time for dealing with emails – after she gets her most challenging task out of the way. She can then feel more in control of her day and is attending to the most difficult job while her mind is still fresh.

- She can mindfully walk to meetings. Rather than rushing, she can walk a little slower, feeling her feet as she does so. Walking in this way will settle her mind and her subsequent air of calmness makes attendees more willing to listen to her.

- She can prioritise lunch. Going to a quiet place and eating her lunch with full attention ensures that she digests the food properly. She can leave her phone on her desk to avoid the temptation of checking emails and texts while she eats.

- She can do her best to give her full attention to colleagues when she’s talking to them. Taking subtle, deeper breaths occasionally will make her more patient because the breaths switch on her relaxation response.

- She can ensure that she goes home on time rather than working late. What she achieves in three hours late at night can be done in an hour when she’s fresh the next morning.

Leaving work on time after a 9-to-5 day can take courage if it flies in the face of your office culture. Sheryl Sandberg, ex-Google executive and current chief operating officer of Facebook, leaves the office at 5.30 p.m. You may think that following her example is impossible but at least consider it. Leaving work earlier, despite making you feel guilty, makes you much more efficient the next day. Finishing work on time is partly a mindset.

Resilience, the ability to effective manage adversity, is the key to managing VUCA at work.

Applying mindfulness in changing times

The current rate of change in the workplace is faster than at any other time in history. The last 15 years have seen an explosion in communications technology and social networking and a rapid rise in economic growth in the emerging economies of India, China, Russia and Brazil. These changes have a big impact on the workplace and affect employees at all levels. How can mindfulness help in managing these changes?

Change isn’t always easy. Sometimes change in the workplace can be met with resistance. The human brain works through habit, which creates a sense of familiarity and security. Poorly managed change can make people feel threatened and they resist it.

Mindfulness is about being aware of the emotional impact of change. You need to prepare employees in advance, providing relevant training if necessary. Following the change, you must be a good listener and respond quickly if employees express frustration or distress.

A unique way of thinking about change is provided by a deeper understanding of the principles of mindfulness. Most mindfulness teaching stresses that the world is in a constant state of flux. Mindfulness exercises demonstrate this perpetual change. Try focusing on one of your senses for more than a few minutes and notice the variety of thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations and distractions that you experience.

The universe is constantly changing. Atoms are continually moving; in fact, scientists are unable to achieve absolute zero, the temperature at which atoms stop moving. If constant change is the way of the world, you need to expect some in your own life. Resisting that change leads to pain.

You need to expect and embrace the change that is bound to come. If you find yourself reacting with sadness or anger to that change, give yourself the time and space to work through those emotions using mindfulness exercises.

- Expect change: If you’re clinging to the hope that change won’t happen, you’re living with greater fear and anxiety. Instead, simply expect change to happen at work. When change doesn’t happen, be pleasantly surprised.

- Embrace change: Jack Welch, ex-CEO of General Electric, advises ‘Change before you have to.’ Try to see change as an opportunity. Write down the benefits of the change and view them as a chance to manage that change. For example, my (Shamash) new boss wanted lots of extra meetings. Initially I didn’t like this change, but then I thought about ways of embracing it. I used frustrating parts of the meeting to practise mindfulness of breath; I enjoyed the extra opportunities to share my ideas. I used some of the time to identify what makes a poor meeting and what makes a good one. You, too, can see change as a chance for growth.

- Anchor yourself in the present: When you’re faced with a torrent of change, you can easily feel flustered. One way of coping with that change is through mindfulness exercises. Even one deep breath taken mindfully can switch on your parasympathetic nervous system, which makes you more relaxed and grounded.

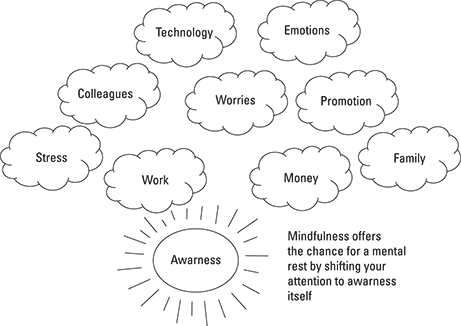

Change can be challenging. But in our experience, regular mindfulness practice makes managing external changes easier because you realise that, beyond your changing thoughts and emotions, that a deeper sense of peace, calm and spaciousness exists that is simply your own awareness. That awareness is always the same, ever present and unchanging. When faced with too much change, you can take refuge in mindfulness to rest your body, mind and emotions in your own, unchanging awareness. Figure 3-1 shows how mindfulness can help you tune in to that unchanging awareness.

Figure 3-1: How thoughts, emotions and the world are constantly changing and how mindfulness can help you to tune into the unchanging awareness that’s underneath all that.

Employing mindfulness for new ways of working

The essence of working with mindfulness is simple: pay attention to the task in hand. By giving work your full attention, the quality and quantity of what you do improves. But there’s more to mindful working than just outcomes. Your level of focus improves, and you give less attention to your normal worries and concerns.

In addition to working with attention, you need to find moments in the day to recharge your mind. The ideal time is between the end of one task and the start of another. After spending an hour writing emails, you can spend a couple of minutes feeling the weight of your body on the chair and your feet on the floor. This mindful awareness of your bodily sensations focuses you on the present moment and is restful for your mind. You feel more energised and prepared for the next task. After a two-hour meeting, you can do a mini-mindfulness exercise (Such as a mindful minute (Chapter 7) or a three step body check (Chapter 6) after everyone has left the room.

Communication is a fundamental aspect of the workplace. On top of giving attention to your own work, and allowing yourself short periods of rest in between, you need to be able to communicate effectively with others. Businesses can be called companies – they involve the companionship of others. As you become more mindful, you’re better able to simultaneously identify the emotions of others and be aware and in control of your own emotions. As a result of this heightened emotional intelligence, people feel drawn to you and are more willing to work with you. A recent survey of 2,600 managers found that 75 per cent of them were more likely to promote an employee demonstrating emotional intelligence than one with a high IQ.

Unmindful use of technology is also impacting success in the workplace. Laptops and phones mean that you can take your work home with you. If you’re not in control of your behaviour, you can end up working through all of your waking hours. That’s not good for you or your work. Having time away from work gives your brain a rest and an opportunity to recharge. Chapter 8 covers how to use technology in a more mindful way.

Building resilience

Too many challenges at work makes you feel overwhelmed and frustrated. In response you trigger your fight or flight mechanism. This threat response, if switched on for too long, leads to inefficient use of your brain and disease in your body. Building resilience is a way of managing challenges more effectively. For more on mindfulness for resilience, see Chapter 5.

Take the example of Thomas Edison, legendary inventor of the light bulb. He famously said that each time he failed, he didn’t view the experiment as a failure; rather he saw it as another way that didn’t work. Seeing failed attempts as stepping stones to success is an example of a resilient attitude. Edison bounced back from attempts that didn’t work to discover what did work. He certainly thrived on success, inventing the phonograph, motion picture and telegraph.

The achievements of Edison may seem hard to emulate. He seemed to be almost born with a positive attitude and destined for success. And, as far as we know, he didn’t formally practise mindfulness! How can mindfulness help you?

As you become more mindful, your tendency to ruminate declines. Rumination is how much you think about and dwell on your problems. Rumination is like a broken record that keeps replaying itself – that argument you had with your colleague, that error you made in your presentation. If you ruminate, you overthink about situations or life events.

Mindfulness may be one of the most effective ways to reduce ruminative thinking because you become more aware of your thought patterns and more skilful at stepping back from unhelpful thoughts.

An online experiment conducted in 2013 in conjunction with the BBC and the University of Liverpool and involving over 32,000 participants, found that people who didn’t ruminate or self-blame demonstrated much lower levels of depression and anxiety, even though they’d experienced many negative events.

Mindfulness helps you to spot those little niggling negative thoughts before they grow too large. And mindfulness helps you to naturally see tough situations at work as challenges to be faced and overcome rather than avoided. If you’re feeling overwhelmed by adversity, mindfulness won’t offer a quick fix. But dealing with each challenge, step by step, combining mindfulness with help from your colleagues and/or a coach, means that you can begin to thrive at work.

- His attitudes and beliefs

- The kind of language he uses to describe a change in the workplace

- The sort of hours he works and what she does to rest and recharge

- How mindful (present) he is when at work

Spending time talking with those who thrive on change in the workplace can help you to see things from their perspective.

Adjusting Your Mental Mindset

‘Your living is determined not so much by what life brings to you as by the attitude you bring to life; not so much by what happens to you as by the way your mind looks at what happens.’

Kahlil Gibran

When I (Shamash) discovered mindfulness, my mindset shifted 180 degrees. Before that first lesson in mindfulness, I was completely goal-orientated. I was halfway through a degree in chemical engineering and wanted a career working for a big corporation. I was only 20 years old, but ever since I was a boy I’d striven to achieve the top grades at school so that I could get into a good university. I aimed to be among the best at university so that I could get a good job, and so on. The obsessive desire for success was draining me. But after that mindfulness class, something shifted. I discovered that life was not only to be enjoyed in the future, after attaining all my goals; life was to be enjoyed right now, here in the present moment. There’s nothing wrong with achieving success and attaining goals, but not at the expense of the here and now. Ironically, by living in a more present-focused way, I’ve been better able to achieve success – the best way to prepare for the future is to live in the present.

Focusing on the present moment

‘The secret of health for both mind and body is not to mourn for the past, worry about the future, or anticipate troubles, but to live in the present moment wisely and earnestly.’

Buddha

We know that our most successful coaching, training and writing sessions occur when we’re fully in the present. Think of someone operating at the highest level of performance: an Olympic athlete. He’s very much in the present moment. Have you ever seen a top Olympic athlete look as if his mind is wandering when he’s performing? I haven’t. He’s fully present because being that way optimises his success. Take the 100-metre sprint. Once the athlete starts running, he’s wholly in the here and now, which leads him to success.

Everyone experiences being fully in the moment at some point. Consider the last time you were fully present at work – what were you doing? How did you feel? How productive were you?

- Do something different: Work can be filled with habits and routines. You sit at the same desk, open the same program, speak to the same people about the same issues. Shake things up a bit. Take a different route to work. Eat something different for lunch or speak to someone on the phone who you normally email. Doing something new makes you switch from auto-pilot to a more present-moment awareness.

- Savour: Living in the present moment can be highly enjoyable. Present- moment living means that you can stop waiting for success in the future. Instead, enjoy the simple pleasures in each moment – the taste of your sandwich, the colour of the autumn leaves on your route to work, the simple smooth feeling of your breath. Don’t dismiss these everyday pleasures – they boost your mood and mental well-being.

- Know that you can always find out more: No matter what you do, room for improvement always exists. Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, Ellen Langer, says we stop paying attention to something when we think that we know it all. Musicians in an orchestra who are told to make their performance subtly different not only enjoy the performance more themselves, so do the audience. By noticing something new, you’ve space to explore, discover and grow – and you shift straight back into the moment. Make work an adventure by seeking to discover subtly new ways to perform your tasks.

Treating thoughts as mental processes

Some people estimate that they have up to 60,000 thoughts a day. If you’ve tried practising mindfulness exercises already, you probably think that’s an underestimate. In the East, the brain’s tendency to constantly go from one thought to another is called the ‘monkey mind’ because it resembles a monkey swinging from branch to branch.

Thoughts can be great. Through the power of thinking, humans have managed to achieve feats way beyond what any other animal on earth has done. We’ve created cities, designed planes and landed on the moon. Unfortunately, we’ve also designed nuclear weapons and heavily polluted the planet.

Thoughts have another disadvantage on a personal level too. If all your thoughts are taken to be true, and if those thoughts are self-critical, your mental well-being suffers. As a result, your performance at work declines too.

- Picture bubbles floating away in the sky. Maintain this image for one minute.

- Imagine that every thought you have can float away in one of those bubbles.

- Let your mind wander. Each time a thought pops into your head, imagine it drifting away in a bubble. Continue to do this for a few minutes. You may have lots of thoughts or very few. It doesn’t matter.

How did you find this exercise? Did your thoughts float away? More importantly, were you able to observe your thoughts? If you were, you’ve demonstrated that you are not your thoughts – you can observe them from a distance.

The thought bubble and similar exercises help to show you an important mindfulness skill: the ability to step back from your thoughts. You may have all sorts of thoughts popping into your head in the workplace, such as:

- I’m useless in meetings.

- I can’t handle this project. It’s too big for me.

- What if Mike tells Michelle about my report? I’ll miss my chance at promotion.

- I hate working with David. He’s too slow for me.

These types of thoughts have an effect on your emotions, bodily sensations and ability to get your work done.

Mindfulness offers a solution. As you become more mindful, you notice these thoughts more often. You are then able to step back from them, seeing them as mental processes in your mind rather than absolute truths.

Being able to step back from your thoughts takes practice, especially in the hustle and bustle of the workplace. For this reason, we recommend that you try out some of these exercises when you’re not under too much pressure. Once your brain gets the hang of how to watch and step back from unhelpful thoughts, you’ve a powerful and life-changing skill.

In the old days of personal development, self-help gurus promoted ‘positive thinking’. For most people, slapping positive thoughts on top of negative beliefs means they just slip off! Instead, you need to become aware of those negative beliefs and see them for what they are – just thoughts.

Use the exercise below to deal with your thoughts and mind state when you’re judging things negatively. It’s a simple process but has long-lasting effects once it becomes a habit for you.

- Notice your thoughts: Focus particularly on unhelpful thoughts about yourself, others or your workplace.

- Step back from your thoughts: See them as simply mental processes arising in your mind that aren’t necessarily true. You can imagine them on clouds, in bubbles or floating away like leaves on a stream. The idea is to create a sense of distance between you and your thoughts – not to just get rid of them.

- Refocus your attention on the task or person in front of you: The more mindfulness exercises you practise, the better your brain gets at dealing with negative thoughts.

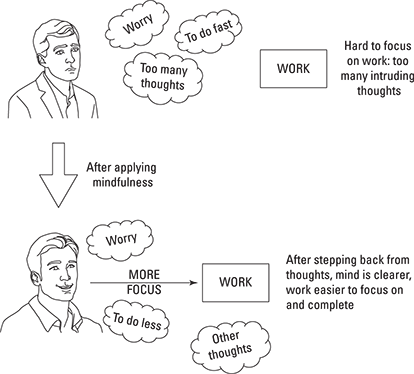

The importance of stepping back from your negative thoughts, and the way they cloud your judgement, is shown in Figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2: The importance of stepping back from the thoughts that cloud your judgement.

Approaching rather than avoiding difficulties

I (Shamash) love the taste of chocolate and don’t like the taste of cauliflower. So I tend to approach chocolate more positively than I do cauliflower. If you could scan my brain when I see these two different foods, you’d probably see different patterns emerging.

Say that work causes you anxiety. You worry about all the meetings you have to attend, the deadlines you have to meet and the colleagues you have to deal with. How do you cope with that feeling of anxiety? Should you continue to face up to the challenges at work and just get on with the uncomfortable feeling of anxiety, or should you avoid anything that makes you feel that way?

You can avoid the feeling by working even harder so that your attention is completely focused on the task in hand and not on your anxiety. Or you can go for a drink every evening after work, causing the emotional sensation to reduce. Or you can start eating every time that feeling arises, so your attention is focused on the food instead of your anxiety.

All these strategies help you to avoid the feeling of anxiety in the workplace. Unfortunately, however, none of them work over the long term. The feeling of anxiety is still there and requires an increasing number of avoidant strategies to help you supress it.

Mindfulness is about approach rather than avoidance. It helps you to approach unpleasant feelings at a pace that’s right for you.

Approaching difficult emotions when you’ve always found a way to avoid them isn’t easy at first. To help you get better at doing so, you need to approach your feeling as you’d approach a kitten. You don’t rush towards a kitten because it gets frightened and runs away. You approach a kitten slowly. First you walk towards it and then you crouch down so that you don’t look too big. Next, you reach out and gently stroke it. Hopefully, the kitten begins to trust you and eventually you can pick it up.

Treat whatever emotion you’re dealing with in the same way. Notice where you’re holding the feeling in your body. Approach the feeling slowly and tentatively, with a sense of curiosity. Gradually you come to fully feel the sensation, just as it is. This experience is like having a kitten in your hand. Unlike a kitten, however, the feeling is likely to change as you approach it.

Sometimes it grows, sometimes it dissolves. But that’s not the point. The point is that you’re willing to feel that emotion and approach rather than avoid it. This empowering move leads to greater emotional regulation – you’ve control over your emotion rather than the emotion controlling you.

Approaching emotions involves a process of non-judgemental acceptance – a key aspect of mindfulness. When you’re practising mindfulness, you’re endeavouring to experience thoughts, emotions, sensations and events as they are in the moment, without trying to judge them as good or bad, desirable or undesirable.

- Sit comfortably and spend a couple of minutes focusing your attention on your breathing or the sounds around you.

- Think of something in the workplace that scares you a little. Bring to mind a difficult presentation, an aggressive colleague or the thought of losing your job, for example.

- Notice any tension in your body resulting from your sense of anxiety.

- Approach that sensation in your body slowly and gently.

- Try feeling the sensation together with your breathing.

- Be aware that you’re approaching rather than avoiding the feeling – a mindful step. Notice whether the feeling changes or stays the same from one breath to the next.

- Refocus on your breathing alone for a couple of minutes before ending the exercise.

Rewiring Your Brain

Your brain is made up of neurons, which are like wires that carry electrical current from one place to another. Each neuron is connected to many others. The brain is the most complex organism in the known universe and scientists still have very little idea about how it works.

If you were at school in the 1970s, you were probably taught that your brain gradually deteriorates as you get older. The prevailing view was that the brain can’t improve itself and that neurons die off as you age. That view was incorrect! We now know that you can create new connections in your brain at any age.

Your brain is unique and shaped by your daily experiences and what you pay attention to. If you’re a violinist, the part of your brain that maps touch in your fingers is actually larger. If you’re a taxi driver in London, the part of your brain responsible for spatial awareness is more pronounced. And if you’re a mindfulness practitioner, the area of your brain that controls focus is more powerful, as is that part which manages emotions. Finally, if you’re a mindfulness practitioner, the area of the brain responsible for higher levels of well-being is more active – the left prefrontal cortex.

Getting to grips with the science of mindfulness

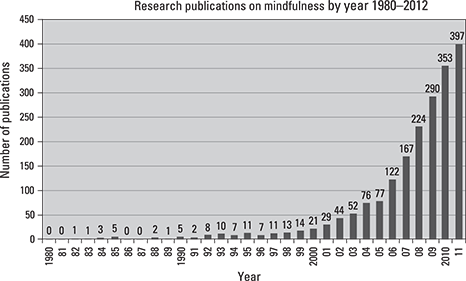

An explosion of interest in the study of mindfulness has recently occurred. Centres for mindfulness have been established at numerous universities (see Chapter 20), both in the UK and all over the world. US examples include the University of Massachusetts Center for Mindfulness, UCLA’s Mindful Awareness Research Center and the UCSD Center for Mindfulness. Figure 3-3 shows the growth in publications on Mindfulness between 1980 and 2011.

Figure 3-3: Growth in research into mindfulness.

Throughout this book we share insights about the effects of mindfulness on the brain. In this section we describe findings from the world of neuroscience. (Chapter 20 provides a list of research articles that you may find interesting.)

Resculpting your brain to make you more productive at work

Most people feel that their mind is all over the place. In fact, some people who practise mindfulness even think that the exercises make them less focused! Studies show that the opposite is actually true. When you sit down to be mindful, you’re much more likely to notice each time your mind gets distracted. Usually, your mind is even less focused – so much so that you don’t even realise it.

Brain scans reveal that even after just a week or so of daily mindfulness practice, the parts of the brain dedicated to the paying attention (which include the parietal and prefrontal structures), become more activated. In other words you are actively improving your brains ability to pay attention. Longer-term practitioners appear to have more permanent changes in the brain, showing a greater propensity to be in the present moment even when in a resting state.

In his most recent book, Focus, psychologist Daniel Goleman argues that incessant use of technology, such as emails and text messages, has rendered young people increasingly distracted. He goes on to say that current research suggests that mindfulness exercises enable the brain to rewire itself and become more focused.

Goleman identifies three types of focus that are required for different types of tasks:

- Concentration: Focusing on one thing only and blocking out distractions – ideal for completing tasks requiring your full attention.

- Open presence: You are receptive to all incoming information – ideal if you’re in a leadership position that requires you to see the big picture and identify how all the different activities help the organisation achieve its goals.

- Free association: Letting go of your old ideas and allowing your mind to drift – ideal when tapping into your creativity.

Mindfulness directly helps to strengthen the networks in your brain associated with concentration and open presence, and allows you to choose to engage in free association when you need to.

If you want to know more about focus, you can find my interview with Goleman on shamashalidina.com

Using mindfulness to increase your present-moment circuitry

Children love stories. Adults love stories. Have you ever wondered why? The brain is designed to be hooked by stories. Stories switch on the visual part of your brain. Because stories are formed of connecting ideas, they tune into the connections in your own brain.

Some people refer to the brain as a story-telling machine. Think about when you first wake up in the morning. Your mind is blank and then, suddenly, whoosh! Who you are and where you live and that long to-do list come to mind.

Your storytelling mind is the ‘default’ network in your brain. In other words, your brain’s normal mode is to tell you stories about yourself and others. For example, ‘I need to finish this project by noon, then I need to have a chat with Paul before I get dressed to meet my editor. I must make sure that I’m on time. That hotel we’re meeting in looks very big. I hope we can find a table. I wonder if my co-author can join us … ?’

That’s the storytelling brain at work – not always terribly exciting and often repetitive. But mindfulness is different and much more interesting. If your brain is in a more mindful state, you’re focused on the present moment, which engages a different circuitry in your brain. You can access the present moment right now by noticing the sensations that your body is experiencing as it sits on a chair. Do you start to become aware of your poor posture or notice tension in your neck? You can now start to notice information from the world around you: the coolness of the book you’re holding, the size of the tree outside, the wispy clouds and hints of a blue sky beyond. That’s present focused attention.

When you’re more present-moment focused, rather than running on your default network all the time, you’re more in control of your life. Instead of finding yourself aimlessly surfing the web, you can catch yourself and choose to get on and finish your work. If you’re lost in thought after thought, you can’t make a choice about what you’re doing until you snap out of the dream. Mindfulness offers you that choice.

- Make a concerted effort to engage your present-moment focus for the next 24 hours.

- Use any free moments in the day to focus your attention on your bodily sensations and breathing or smells, tastes and sights. In any given moment when you’d usually let your mind wander, choose one of the above and observe. Focus your attention on just that one thing.

- Record your observations. What did you discover or notice? Is your mind more clear and focused? How did you cope with the distractions that your mind created? If 24 hours was too challenging, try one hour.

Developing Mindfulness at Work

This book is filled to the brim with mindfulness exercises to do on your own and ways to integrate mindfulness into your workplace. This section describes some of the key principles of true mindfulness, which are important both in the workplace and beyond. Some of these principles have emerged from ancient practices, developed by millions of people over thousands of years. Take a few moments to consider the key aspects of mindfulness at work and whether these ideas resonate with you.

Examining intentions and attitudes

Mindfulness is much more than just paying attention in the present moment. Mindfulness has three aspects: intention, attention and attitude.

Intention is clarifying what you hope to get from mindfulness. Your intention when introducing mindfulness in the workplace may be to:

- Increase focus

- Encourage creativity

- Reduce anxiety or stress

- Improve well-being

- Increase productivity

- Generate bigger profits

- Find greater meaning in your work

- Improve your relationships at work

- Develop your resilience

Your intentions play a huge role in your mindfulness practice. You may practise mindfulness for very personal reasons or to benefit your team, your organisation or even the world!

Your intentions in everyday life may be so subtle that you don’t recognise just how important they are. For example, take the example of breaking a window. A thief may break your window to enter and steal something from your home. A firefighter, however, may break your window to enter your home and rescue you from a fire. The action is exactly the same but the intention is totally different. In the same way, being clear about your intention has a big effect on your practice.

At first, you may practise mindfulness for yourself. And that’s fine. But as you develop your practice, you may like to consider being mindful for the benefit of others too. For example:

- To improve relations in your work team

- To be more productive so you can serve your customers better

- To be more emotionally intelligent so you can relate more effectively with your colleagues

- To help calm the anxious atmosphere in the office

These intentions aren’t right or wrong – but may help you to find greater meaning in your mindfulness practice and your working life. And people whose sense of meaning is connected to their work tend to be happier, healthier and more successful in their role – a triple whammy! See the nearby sidebar ‘Job, career or calling’ for more on what motivates people at work.

In addition to intention, your attitudes are also important. Jon Kabat-Zinn, co-developer of mindfulness-based approaches in the West, recommends developing the following attitudes to life.

Being non-judgemental

Your mind is constantly judging experiences as good or bad. Mindfulness practice offers time for you to let go of those internal judgements and just observe whatever you’re experiencing, accepting the moment as it is.

Being patient

Mindfulness requires patience. You need to bring your attention back to the present again and again. If you’re naturally impatient, mindfulness is probably the best training you can undertake! But it won’t be easy. You need to experience sitting with the discomfort of impatience. With time, the feeling dissolves. Being non-judgemental with your feelings helps you to accept and be with them, no matter how impatient you feel.

Adopting a beginner’s mind

If you adopt a beginner’s mind, you undertake each mindfulness practice as if the experience was a completely new one. And not only mindfulness – to work with a beginner’s mind means that you approach your work with freshness – as if you’ve never done this kind of work before. Adopting this attitude helps you to switch off your habitual, automatic ways of doing things. As you become more experienced in mindfulness, the beginner’s mind is particularly important. Always practise mindfulness as if you’re a beginner!

Developing trust

Mindfulness takes time to show its benefits. In that time, you need to be able to trust the process. If you’re going through a difficult time at work, you also need to be able to trust your own inner capacity to work through the challenge with the support of mindfulness, together with any other support that you can access. Trust is about believing that things can be better. And with that mindset, you’re willing to try something new. Developing trust involves noticing and respecting your doubts, but not letting your doubts run away with you. The greatest of scientists needs to trust that her experiment may lead to new discoveries, otherwise she wouldn’t bother trying it in the first place. Try to adopt the trusting and open attitude of a scientist as you learn to be more mindful.

Learning to be non-striving

To strive means trying to reach a future goal, whether that’s an internal goal of feeling happier or more focused, or an external goal of achieving financial success. Striving engages the ‘doing mode’ in your brain. In this state, you experience a sense of inherent dissatisfaction with the way things are in the present moment. This dissatisfaction drives the action to achieve the goal.

Mindfulness is about non-striving. To be mindful, you need to let go of your constant desire to achieve. Just be with whatever experiences show up; simply observe them with curiosity and make no judgements. You don’t have to feel calm or relaxed; you simply need to be present in your moment-to-moment experiences as best you can.

Being accepting

Acceptance is a fundamental aspect of mindfulness. To accept means to stop fighting with your present-moment experience and just be aware of whatever is happening. For example, if you feel discomfort in your body when you’re practising mindfulness, and shifting your posture doesn’t ease it, just acknowledge the sensation and let it be. Giving presentations may make you feel anxious. Mindfulness lets you acknowledge the anxiety as an interesting feeling and then ignore it.

Letting go

When I (Shamash) was writing my first book, I struggled. I wanted it to be perfect. But the more I strove for that, the longer the book took me to write. When I finally let go of the idea of perfection, the words began to flow. Letting go was the key.

Consider what you’re holding on to. A job that isn’t right for you? Ways of working that are no longer effective? Even more importantly, are you holding on to ideas that are limiting your potential, such as ‘I can’t handle this project’ or ‘I’ll never be able to give a speech’? Perhaps you need to let go of your old ideas.

Letting go is an act of freedom. When you let go of old ideas, beliefs, people, jobs or ways of working, you create space for the new. When practising mindfulness, you need to let go of each stream of thought that you notice. The process is a continuous movement of observation and letting go.

Sometimes mindful awareness results in a complete sense of letting go and being in your moment-to-moment experience, with full acceptance, total peace and joyful effortlessness. If this experience ever happens to you, remember to let it go too!

Remembering that practice makes perfect

Monks practise mindfulness for years. Early scientific research into mindfulness investigated the effect it has on monks. Brain scans revealed that monks’ brains operate far more effectively than those of people who don’t practise mindfulness. The researchers also found that the more practice a monk had undertaken, the greater number of positive changes observed. Monks have an incredible ability to focus, can manage their emotions very well, experience lots of positive emotions (that’s why they’re always smiling!) and rarely, if ever, lose their temper.

The good news is – you don’t need to become a monk to benefit from mindfulness. Positive changes have been observed in the brains of people who’ve been practising mindfulness for just 10–20 minutes a day for a few days.

Daily practice is the key. Consider the process of discovering how to ride a bike. If you spend just one minute a day practising, you eventually get better but doing so takes years! If you practise for 20 minutes a day with a teacher, you may be able to ride within a week or two. Once you get the hang of riding a bike, to be able to cycle faster you need regular practice. You may need to train with a coach, read books about cycling, meet other cyclists to share ideas and so on.

Mindfulness is similar. You need to practise regularly, and the more time you can dedicate to being mindful, the better you get at it. You can start slowly with short mindful exercises and gradually build up to longer sessions. If you want to get really good at mindfulness, you need to read about it, get a coach or trainer and practise diligently.

Experimenting with mindfulness in the workplace lab

What makes a good scientist? Someone who has a theory, tests it out and perseveres until it’s proven.

We encourage you to think of your work as a laboratory – time to pop your lab coat on! Think of your job as a place where you can test out the effect of mindfulness on the quality of your work, your relationships with colleagues, your productivity or whatever outcome you’re hoping for. You’re much more likely to adopt mindfulness if you find out that the exercises work.

- Record how things are for you now, without mindfulness. You can record how much work you’ve achieved every hour or how well you’re getting on with your colleagues, how focused you are or even how much you’re enjoying your work at the end of each day. Measure whatever you’re interested in ultimately changing. As with any good budding scientist, keep clear records. Enter data on a spreadsheet, note data in a journal or even record findings on your phone.

- Integrate mindfulness into your work for a few weeks. You can do a 10-minute mindfulness exercise at the start of the day, or enjoy three mindful pauses spread out over the day, or set reminder alarms on your phone to be mindful and focused while you’re working. Continue to record your productivity or whatever else you’re measuring.

- Analyse your results. What effect did mindfulness have on whatever you’re measuring? Notice what worked for you and stick with it. The longer you practise, the more effective your mindfulness is.

Acting ethically for the organisation and its people

To behave in an ethical manner means doing what you consider to be right. Being ethical is vital for all parts of the organisation, but especially so for its leaders. If the leaders of your company are unethical, other employees are tempted to follow suit. The example set by leaders holds far more weight than all the words in the ethics handbook.

Not only is acting ethically important in itself, it has numerous benefits:

- Safeguarding assets: If your organisation has an ethical culture, the staff respect the company’s assets. So office supplies won’t go missing and employees won’t use the phone for personal conversations. When employees feel proud of their organisation and work with integrity, they respect the company’s supplies and equipment.

- Quality of decision making: Decisions are often based on ethical choices. The more tempting decision may not be the most ethical one. Ethical decisions based on transparency and accountability lead to the long-term health of the organisation.

- Public image: An ethical organisation is far more attractive to the general public. When unethical actions come to light, a company’s image can be destroyed overnight. The public would like to see you value your staff, the environment and those less fortunate rather than profits alone.

- Teamwork: If your organisation communicates its values and ethics to employees, they can better align their own values with those of the company. When these positive values are authentic and acted upon, employees feel proud of their organisation and what it stands for. The quality and quantity of work increase alongside increased intrinsic motivation.

Examples abound of multinationals incurring huge financial losses as a result of acting unethically. Lack of corporate integrity can bring down a whole organisation.

Mindfulness can affect the ethical stance of everyone in the organisation. Ethics are ultimately based on decisions. When mindful, you’re more aware of the decision you’re making and the impact that it has. As all decisions contain an element of emotion, you can use mindfulness to focus on those emotions that result in more ethically sound decisions.

Marc Lampe, Professor at University of San Diego, argues that mindfulness improves cognitive awareness and emotional regulation, positively contributing to ethical decisions.

Common sense agrees. Mindfulness is based on attitudes such as compassion, curiosity and self-awareness. The non-reactive and caregiving stance that mindfulness promotes is bound to lead to morally sensitive choices in the workplace.

Living life mindfully

To get the best results, mindfulness needs to be practised at home as well as at work. If you live mindfully when you’re travelling, at home, with friends or engaging in hobbies, you’re more likely to be mindful when you’re at work too.

If you’re training to run a marathon, you don’t just eat healthily during the day and then pig out in the evening – you need to live a healthy life. To develop mindfulness, you need to live mindfully.

- When conversing with your partner, give them your full attention: Notice your tendencies to interrupt, argue or ignore. Instead, make a concerted effort to step back and see your partner afresh, with a sense of gratitude for what they offer to the relationship. See relationship interactions as a chance for you to grow and develop rather than a means to fix or change others. Seeing the faults in others is often much easier than recognising your own shortcomings.

- When you’re with your children, know that love and attention go hand in hand: When you play with them, listen to their stories about school or help them with their problems. Doing so makes your children feel more loved. You can’t always give them your undivided attention, of course, but if you usually do some work in the evening and always see your kids as a distraction, redress your priorities.

- Housework is a great way to practise mindfulness: The work doesn’t involve too much thinking, the processes are repetitive and there’s a clear focus for attention. Take ironing, for example. Rather than trying to finish it as quickly as possible, take your time. Enjoy the heat coming off the shirt, the sensation of the iron gliding over the material, the smell of a freshly washed garment and the beauty of a pressed shirt. Focusing your attention in this way isn’t only satisfying, but is another way to deepen your mindfulness.

- Cook and eat with awareness: Taking time to cook a meal is a wonderful discipline. Every time you chop a tomato, feel the knife slicing through it. Listen to the onion sizzling in the frying pan and smell the freshly cooked herbs. Cooking is a great way to develop your mindful awareness and improve your health because you decide how much (or little) sugar and fat goes into your cooking, not some restaurant chef. Use fresh, organic, local ingredients when you can and enjoy the taste of your meal. Eating slowly, tasting each morsel and being grateful to have food available is all part of mindful cooking and eating.

- Be aware of your phone, TV and Internet usage: If your work involves looking at screens all day, take a rest when you get home – take a screen break. Spend more time talking to your family and friends; set aside time for walking, reading or going to the theatre. Ensure that you have things to do in your diary that involve getting out and about.

To live mindfully is to live with greater wisdom and compassion. Wisdom is about the choices you make and your attitudes to life. Compassion is responding kindly to your own suffering and that of others. Mindful awareness helps you to wake up to your own life and make living and working with greater wisdom and compassion a reality. You’re able to act with greater integrity and respond with increased empathy. You’re in tune with your inner values and are sensitive to the needs and values of others.

- Think about the wisest people you know. What sort of work do they do? How do they behave when they’re at work? What is their attitude to life? How mindful are they when they’re at work, at home or with friends? How balanced is their lifestyle? Spend time with them and share what you think of them. Find out how they came to be so wise.

- Think about the kindest, friendliest or happiest people you know. How do they behave when they’re with others? What sort of words do they use? How do they measure success? Try spending more time with them and find out what they do to develop these positive qualities.

To better manage change in the workplace, try these tips:

To better manage change in the workplace, try these tips: Think of someone in your workplace who seems to thrive on change and whom you respect. Identify:

Think of someone in your workplace who seems to thrive on change and whom you respect. Identify: Approach a challenge rather than avoid it, if you can, and discover how to accept the sensations that it produces. Being able to approach your difficulties makes you feel more confident and you’re less likely to let your emotions control your life.

Approach a challenge rather than avoid it, if you can, and discover how to accept the sensations that it produces. Being able to approach your difficulties makes you feel more confident and you’re less likely to let your emotions control your life.