Chapter One

Urban Design in Victorian London: The Minet Estate in Lambeth C.1870 to 1910

DAVID KROLL

The Minet Estate is a mainly residential area of around 60 hectares in south London in today’s London Boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark. This chapter examines the planning and design process of the Minet Estate and discusses the roles and relationships of those involved in creating the housing: surveyors, architects, builders, landowners and developers. The focus is on the main phase of its development, which took place from c.1870 to 1910. The research is based on an unusually comprehensive archive of a Victorian housing estate in London, a detailed study of which has not previously been undertaken. The Minet Estate provides an example of Victorian housing development that is architecturally more diverse than is generally the case with housing projects today. It involved a large number of different small builders, designers and architects, and a level of complexity and sophistication in its planning that is rarely appreciated in the literature. This case study contributes to a more detailed understanding of the planning and design of late Victorian speculative housing, which has proven to be unusually long-lasting, adaptable and desirable – key measures of sustainability.

Why the Minet Estate?

At the time when the Minet Estate was built up in the late nineteenth century, London was still expanding rapidly in area and most new housing was built on ‘green fields’, on land that was previously agricultural. The height of the housing on the Minet Estate varies, ranging from a mixture of terraced, semi-detached and detached houses of two to four storeys to several blocks of flats of four to five storeys. In contrast, most recent large-scale development within Greater London, such as the Athletes’ Village in Stratford and the Millennium Village on the Greenwich Peninsula, takes place on brownfield or greyfield land, and often at significantly higher densities. What, then, can we learn from a past that took place within a very different urban, economic and political context? What are the parallels to the challenges we face today?

Firstly, new greenfield development at densities such as the Minet Estate can still take place today, but usually outside Greater London. In fact, new large-scale housing development at various densities outside the Green Belt has been one of the approaches to the tackling of London’s housing crisis.1 Furthermore, a highly controversial government consultation proposes to allow councils to allocate land on the Green Belt for starter homes.2 In light of these discussions, it is worth remembering a particularly productive period of house building that has left us with such a remarkable legacy.3 The Victorian houses that survived post-war slum clearance are today among the most popular housing types in London and have demonstrated an extraordinary longevity.4 The Minet Estate has all those qualities and characteristics that Christopher Costelloe has described as exemplary about ordinary Victorian housing: ‘density, cohesiveness, quality of materials, walkability, generally good public transport, and their infrastructure of pubs, corner shops and public buildings’.5 A recent research study on ‘sustainable suburbia’ by MJP Architects underlined Costelloe’s assessment and praised Victorian terraced housing as particularly positive for ‘sustainable’ densities of generally over 50 dwellings per hectare that promote walkability.6

The example of the Minet Estate is also pertinent considering that not all new development within Greater London is necessarily high-rise. Current discussions of how to build more housing also involve suggestions to raise densities in existing low-density areas, but in a way that allows them to retain their ‘family friendly’, suburban character.7 The Minet Estate is a successful example of such an area with housing at varied densities. It could be an appropriate model in particular for the outer suburbs of Greater London and the commuter belt. The houses built on the estate range from two to four storeys and are examples of the kind of Victorian terraces, detached and semis that are familiar in many areas of London. Unusually for this part of London at the time, the estate also has a number of blocks of flats, which were built around the turn of the century when the estate was running out of available land. The Minet Estate hence comprises an interesting mix of housing at different densities, originally built for varied occupant groups.

Apart from parallels to the present in terms of densities and housing types, a case study of the Minet Estate is also interesting with regard to the general processes of how housing was planned and developed, taking account of the roles and relationships of those involved in production such as surveyors, architects, builders, landowners and developers. Recent UK governments have tried to involve a greater variety of stakeholders in the planning and production of the built environment, as is reflected in legislation such as the Self-build and Custom Housebuilding Act 2015 and the Localism Act 2011. And yet, large-scale housing projects in the UK are generally built up by one house-builder in a centrally managed and planned process. In light of this discourse, it is interesting to note that in the nineteenth century, areas like the Minet Estate were developed by a large number of different stakeholders with wide-ranging influences on matters of design and construction. In the case of the Minet Estate, these diverse influences resulted in considerable variety in the architecture, ranging from variations in style and detailing to those in dwelling type and layout. The lessons that can be learnt are not only relevant to government and planning policy, but also to the growing custom-build movement.

A final point to learn from the Minet Estate is linked to the other points above and concerns the finance of house building. This point is particularly relevant as the London housing crisis is firstly an affordability crisis. In terms of cost, the financial entry threshold to house building for a builder-developer or owner-occupier was much lower on the Minet Estate than it is today because there was no up-front fee for the land. Instead, the land was rented on an annual ground rent. This was an important reason why small builders without large initial capital were able to become house-builders. The case of the Minet Estate suggests that involving a greater number of stakeholders and decision-makers in the production of housing is also a matter of finance, in particular in relation to land costs, which are at a historic high.8 Otherwise, initiatives such as localism remain only a token to stakeholder involvement. For custom-build to have a chance at a larger scale, for example, and for people without significant capital like young, first-time buyer families to start building their own homes, financial thresholds to obtain suitable land would need to be lower than at present.

What then makes the Minet Estate more worthy of study than other exemplary late nineteenth-century estates? One key reason is the archival material available.9 The Minet Estate archive is one of the most comprehensive archives of a London Victorian housing estate that is accessible to the public, yet it has so far not been discussed in the literature in detail. The estate also presents a suitable case study because decisions taken in the early stages of its development, as well as their influence on the architecture, can be reconstructed from the archival sources. Finally, the Minet Estate is useful as a case study because it was in many respects ordinary, rather than avant-garde, and many of the findings are transferable to other London estates of the period.

While the ‘ordinary’ Minet Estate is not pioneering or experimental like Bedford Park or Hampstead Garden Suburb, it is in some ways quite unusual. For example, the later phase of the development was not purely profit-driven but partly philanthropic, which can be seen in the donation of a public park (Myatt’s Fields) and a library (the Minet Library) by the owner, William Minet. The estate was also probably unusually well managed and resourcefully planned, which has left us with largely very attractive and still very popular residential architecture. Although the housing on the estate accommodated people with varied income levels, many of the larger houses in particular were built for, and initially occupied by, fairly well-to-do tenants. Thus the estate is not representative in every respect. However, the way it was built up by following the then typical English leasehold development system means that there are similarities with other housing estates of the time. Many of the basic conclusions of this chapter are therefore also often applicable to other privately developed Victorian and Edwardian housing estates.

Systems of Estate Development in the Nineteenth Century

While it is difficult to define what constitutes a typical Victorian estate, certain generalisations can be made. As a fundamental distinction, speculative housing estates of the period were developed in one of three ways:

- By contracting builders directly to construct the houses

- By selling the land as freehold to builders

- By letting the land as leasehold to builders

Each of these systems of estate development had an impact on the resulting architecture and on the degree to which the estate owner influenced the development. As a context to the Minet Estate case study, it will be useful to touch briefly on these different methods of development.10

The first of these three methods – to contract builders directly to build all the houses on an estate – was uncommon in the late nineteenth century because of the high risk and initial investment involved. Exceptions can be found, such as some of the houses built on the estates developed by Archibald Cameron Corbett. But even with the financial resources of one of London’s largest developers of speculative housing at the time, Corbett abandoned his experimentation with direct contracting of building work and reverted to the leasehold and freehold development that was standard for housing estates in late nineteenth century London.11

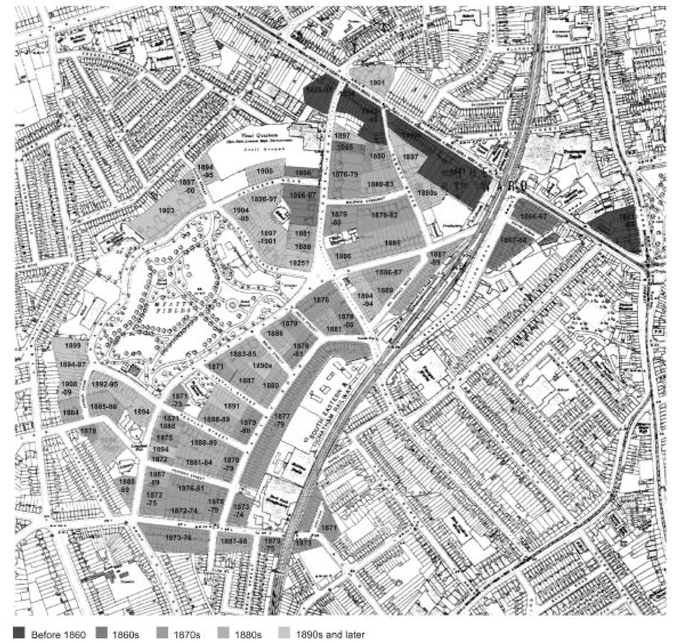

FIGURE 1.1,

This map of the Minet Estate was begun in 1843 by Messrs Driver, the estate surveyors, and updated until about 1890 to record all leases. It was an essential estate-management tool. A smaller separate plot to the top right was sold off in 1872.

In this more conventional practice, rather than financing the building of the houses themselves, the estate owner spread the financial risk to a number of different builders by letting individual building plots as leasehold or by selling plots as freehold. The pattern of dividing the land along roads into small adjacent plots (large enough for the construction of a house) was ideal for these systems: a small speculative builder could raise the funds for building a house on one of the plots; larger builders who were able to raise sufficient capital could take on a number of plots and sometimes entire streets, or occasionally even a number of streets. Large house-builders who purchased, developed and built whole estates, however, were rare until the inter-war period, when it became easier for builders and also buyers of houses to obtain finance.12

The third method – to develop an estate by letting land to different builders as leaseholds – was very common in the nineteenth century, but was in decline towards the end of the century and seems to have been hardly used after 1914.13 Land was leased to speculative builders in the same way as it would have been leased to farmers when it was in agricultural use. The estate owner would charge an annual ground rent which was paid by those who owned the leasehold at the time. After the lease fell in, often after 99 years, the land returned to the freeholder, often an heir of the estate owner who agreed the lease.

By letting land as leasehold, the estate owner usually had a longer-term interest in the development, and it was therefore in his interests to retain a higher degree of control over the planning and design of the housing. This control could range from a detailed masterplan to a more indirect influence consisting of the management and approval of the builders’ own designs. The long-term financial return from a leasehold development was potentially significantly higher than from selling the freehold: the annual ground rent could provide a continuous source of income for the estate owners and their heirs. Most of the Minet Estate was developed using this third method, by letting land as leaseholds to various builders (Figure 1.1). Only the blocks of flats were constructed with the first method of directly contracting the work to builders.

History of the Minet Estate before 1870

The Minet family descended from Huguenot refugees fleeing persecution in France in the 1680s.14 Hughes Minet bought the estate in 1770 after retiring from a successful career in banking. Until the nineteenth century, most of the area and its surroundings remained agricultural, with the exception of a few buildings on Camberwell Green and Camberwell Road. From 1819 onwards, the first speculative housing on the estate was built along Camberwell New Road, soon after it had been constructed to connect Camberwell Green with Kennington Common. However, building activity on the estate was still minor with most of the houses on Camberwell New Road dating from much later, 1838 to 1845.15 James Lewis Minet, the estate owner at that time, did not initiate any significant building activity on the remainder of the land until the late 1860s. By then, much of the surrounding area had already been built up.16

The approximate 1870 start date for the main phase of the estate’s development was due to a combination of factors. One was simply that the growth of London had reached the area, another that a railway line was constructed in the early 1860s on the edge of the estate. For the railway tracks, station and associated buildings, James Lewis Minet sold part of the estate to the London Dover and Chatham Railway, which disrupted established leases and prompted the first substantial phase of housing development on the estate.17 Camberwell New Road Station,

located in the north-east part of the estate, opened in 1862 and a number of houses and shops were built across from the station by 1870.18 However, the main phase of development started when James Lewis Minet began to implement a long-term plan by leasing a large part of the estate to the builders Parsons & Bamford.19

Building on the Minet Estate 1870 to 1885

Most of the estate was built between c.1870 and 1910 in two principal phases, first under James Lewis Minet’s ownership and then under that of his son William Minet (Figure 1.2). In both of these phases, the leasehold system was a key planning mechanism which provided the legal framework and also shaped the architectural form and layout. The two phases, however, were also distinctly different.

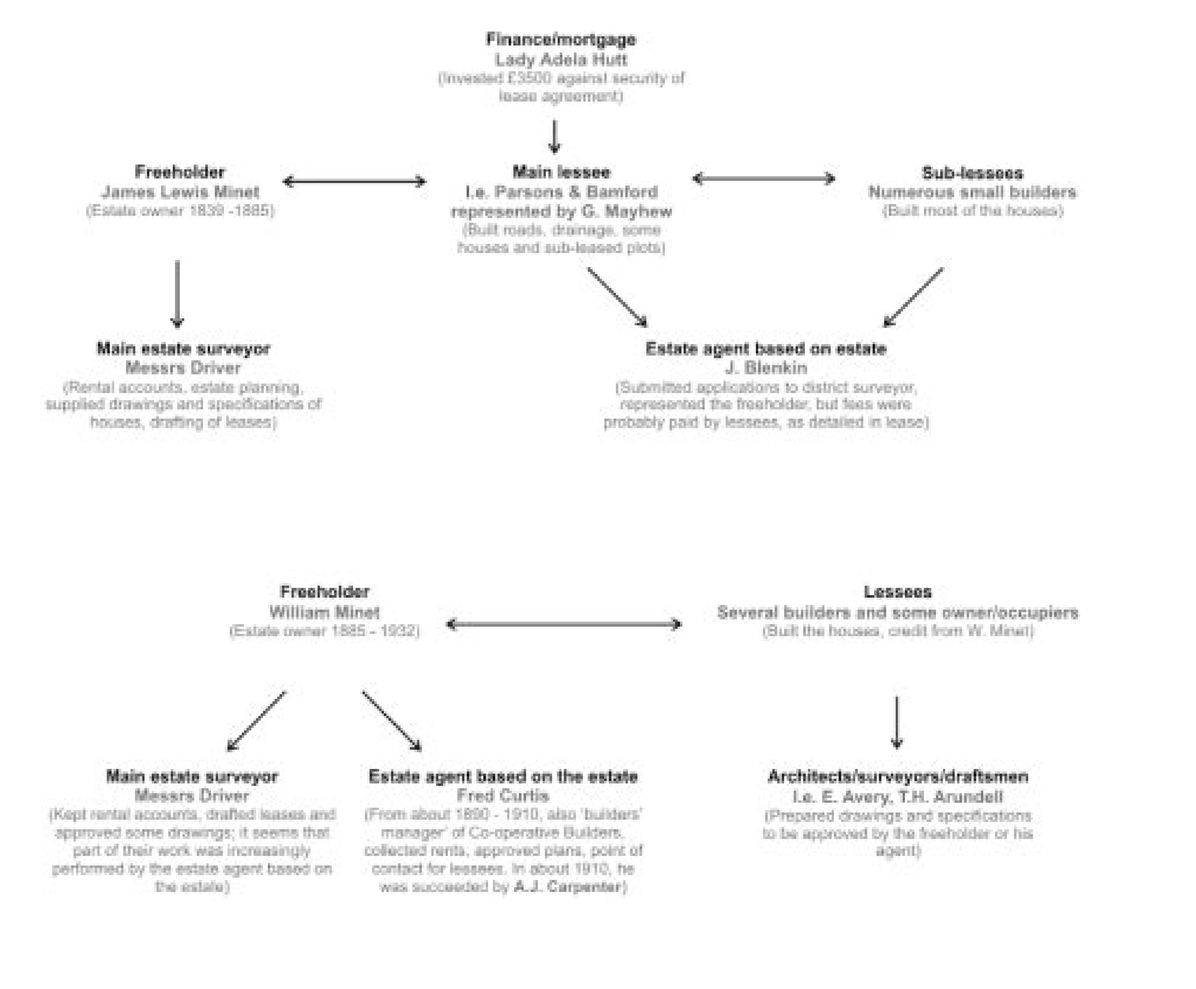

The planning of the first phase (c.1870–85) was more controlled in that there was an overall masterplan to which house builders needed to adhere. The lease agreement between James Lewis Minet and the builders James Henry Parsons and Samuel Bamford, with the solicitor George Mayhew as their representative, had a key influence on this first phase.20 The agreement was drafted by Messrs Driver, surveyors who had an important role in the development of the estate. The firm had managed the estate on behalf of the Minet family since 1818 (then trading as A & E Driver), and Messrs Driver not only prepared maps and surveys of the property, but were also responsible for drafting and administering lease agreements, and for collecting and keeping a record of the ground rents on the Minets’ behalf. The Minet Estate was one of many properties that Messrs Driver managed in the nineteenth century. In 1869 the firm was, in fact, one of the most eminent surveyors, auctioneers and land agents in London, involved in many high-profile

FIGURE 1.2,

This map shows how the Minet Estate was developed and leased in segments. Construction generally started soon after the lease start dates shown.

property transactions of the time.21 The size of the Drivers’ business suggests that the Minet Estate was not unique, and that it was probably managed in a similar way to other estates on the company’s books. Surveyors at the time also had an ‘urban design’ role on estates to be developed, as they were generally responsible for the layout of roads and building plots – and often even for the design of houses.22

As context for what I am, with conscious anachronism, referring to as the urban design of the estate, it should be noted that planning approval by the local council, as we know it today, did not yet exist. Building applications in the 1870s were subject to compliance with the Metropolitan Local Management Act (in its 1862 revision), but the process was closer to today’s building control application than to a planning or development control application.23 A building application then was about compliance with health and safety concerns such as structural safety, fire safety and public health (drainage). The Metropolitan Local Management Act, and later the London Building Acts, also contained basic urban planning rules on building heights, minimum street width and alignments of street facades with a building line.24 However, a building application would pass as long as it complied with these basic general rules. This lack of development control in the sense we understand it today, however, also meant that the role of the estate owner – or the estate surveyor as the owner’s agent – was particularly significant in coordinating the architecture.

In relation to the process of Victorian urban design, the Parsons & Bamford lease agreement is a useful document in many regards. At first glance, it simply appears to set out the conditions of sale, but a careful read of its ten handwritten pages of legal jargon reveals that there is more to it. Besides its legal and financial implications, the leasehold agreement also entailed a meticulous plan for the development of the estate – what we might now call an architectural masterplan. The Parsons & Bamford lease agreement was accompanied by a map which set out streets, plot sizes and also house types (Figure 1.3). Elevations and floor plan templates for the houses were provided by Messrs Driver for use by the builders.

The distribution of the houses by cost reflected economic demands and also social hierarchies of the time. Cheaper houses were allocated on less desirable plots, expensive houses on the more desirable plots. A similar layering of the cost of houses around the railway can be found in other areas in London: the housing between Hither Green Station and Manor House Gardens in south-east London, for example, shows a similar gradual transition from small working class terraced housing near the railway to upper middle class semi-detached and detached houses nearer the park. The 1891 census confirms that in Carew Street on the Minet Estate (house type E, the least expensive house type, with a minimum value of £300), for example, those listed as household heads generally held manual occupations, such as plumber, builder, cabinetmaker, milkman, laundry man or painter.25

It is interesting to note that one of these type E houses, originally built for those on lower incomes, was sold in November 2015 for £735,000.26 The houses along Paulet Road (house types C and D, with a minimum value of £600) were rented by a higher number of those with clerical occupations (Figure 1.4). The houses with shops (house type F) were located near Camberwell New Road Station. Unsurprisingly, with the station closed, many of the shops have since been converted for residential use.

FIGURE 1.3,

Map of the Minet Estate reconstructed from Parsons & Bamford lease agreement, setting out the types of houses to be constructed by cost, as well as the location of other buildings such as pubs and shops.

FIGURE 1.4,

Houses in Paulet Road, an example of D-type houses with a minimum value of £600. Built in the 1870s by different builders using the floor plan and elevation template as defined in the Parsons & Bamford lease agreement.

What is particularly interesting about the Drivers’ map is that there was in fact a blueprint setting out the type and cost of the houses (and with it a social structure) before they were built. The architecture was the result of a conscious and well-coordinated effort of planning it in this way. The type and size of houses to be built was not, as often assumed, simply left to the builders. When the houses were designed in the 1860s and 1870s, their typology and sizes were also no longer determined by the building acts. They were, however, probably still influenced by them, as the house classes, established for taxation purposes in the 1774 Building Act, had only been abolished with the 1844 Metropolitan Building Act.27

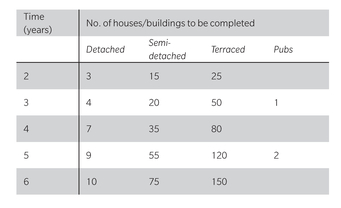

When the Minet lease was drafted in 1869, most of this new part of the estate was expected to be completed within six years, in line with gradually increasing ground rents, to which Parsons & Bamford agreed (Table 1).28 The remainder – about another 65 houses – was to be completed after nine years. The pace at which sub-leases were taken up by other builders, however, was not in line with the expectations of the lease agreement. The six-year plan with an annual ground rent increasing to £1,008 was therefore never put in place. It took nearly two decades for the whole of the Parsons & Bamford plot to be built up, rather than the expected nine years.

Despite the uniform appearance of the houses determined by the Drivers’ scheme, they were not built by one contractor, as would usually be the case today. Parsons & Bamford only completed a few of the houses themselves. On their behalf, Mayhew sub-leased most of the building plots to other builders at an annual ground rent for a period of 99 years from 1869. For 27 Paulet Road (the rear of which was facing the railway depot), for example, Mayhew paid £1 to James Lewis Minet in annual ground rent, but he sub-leased the same plot to the builder Richmond Nurse for £2.29

Of course, in return for this increase in value, Mayhew, Parsons & Bamford had the additional costs and responsibilities of building the roads and services, and of managing the development. This system of leasehold development helped to facilitate construction by a multitude of builders and also acted as a de facto financial lending mechanism (Figure 1.5). On the Minet Estate, there was no up-front fee for leasing the land and also no rent in the first year. This meant that the initial financial outlay required for building houses was much lower than it is today, when prices of land in London are generally higher than the cost of a house built on it. The only funds that builders needed were those for materials and labour.

TABLE 1

Completion schedule from Parsons & Bamford Agreement, 1869

The reason that the houses constructed in the first phase have a uniform, controlled appearance was because the street facades had to be built to elevations provided by the estate surveyors. An estate agent, J Blenkin, was based in an office on the estate, and part of his role was to check that the houses were completed in line with these elevations.

On closer scrutiny, however, it becomes apparent that, as specified in the lease agreements with the builders, only the elevations were tightly controlled. The leaseholders appear to have had influence on layout, interior decorations and fit-out, which is reflected in variations of the standard floor plan types in the building applications to the district surveyor. The leaseholder-builders largely lived locally and were also often occupants of their own houses while construction of their next one was under way.30 They therefore had a significant stake in the success of their product, both as occupiers and because it formed the basis of their livelihood. Even in a tightly controlled and ‘masterplanned’ housing development, such as the first phase of the Minet Estate, the freedom for customisation and stakeholder involvement appears greater than is usually the case in house building in England today, when houses are generally sold as finished, standardised products.

This degree of customisation of the layout and fit-out did not cease when the houses were first built. While the street facades have remained nearly unchanged to this day, the interiors of the houses have changed significantly. These changes range from updates of the décor and building services, to substantial reconfigurations of the dwellings.

Many of the houses of this first phase of the Minet Estate development have since been converted into flats, reflecting today’s greater demand for smaller dwellings in the area.31 That the buildings can accommodate such reconfigurations is a testimony to their adaptability and durability. Despite those changes, the intentions of the original masterplan and lease agreement are still reflected in the buildings today; the facades remain largely unchanged, but the interiors have been customised and adapted to suit changing occupation patterns, fashions and ownership.

FIGURE 1.5,

Map of the Minet Estate (detail of Figure 1.1) with names of first leaseholders, often but not always the builder. This does not clearly distinguish between lessee and sub-lessee. The map is therefore only indicative. Even so, it illustrates the number of different lessees and the builders involved.

Building on the Minet Estate 1885 to 1910

The second phase of house building on the Minet Estate was distinctly different from the first. James Lewis Minet took a hands-off approach to the development of the estate and left the day-to-day management of design and construction to others, such as the estate surveyors, Messrs Driver. After 1885, however, with the succession in ownership to William Minet, the planning of the estate changed fundamentally. William Minet took a much more active interest in the day-to-day work of estate development and also directly appointed his own estate agent, Fred Curtis, who was based on the estate. William Minet visited weekly, approved many of the drawings personally, and Curtis did not take any significant decision without first consulting him.32 Curtis was responsible for rent collection and the management of building agreements and maintenance work. Curtis’s role was also to manage the Cooperative Builders, who William Minet helped to set up in 1889 to construct a number of blocks of flats on the estate and provide continued maintenance of the buildings.33

A key change in relationships occurred after 1885. During James Lewis Minet’s ownership, the elevations and house types had been imposed on the various lessees by the freeholder (Figure 1.6); under William Minet, however, house designs would now be proposed by the leaseholders and then approved by the freeholder. These two systems were not unique to the Minet Estate: most leasehold housing at the time would have been developed in either one of these two ways, with the design either imposed on the lessee by the freeholder or proposed by the lessee and then approved by the freeholder.

The difference between these two systems might seem like a mere formality, but it had clearly visible architectural consequences and explains why the parts of the estate planned and built before 1885 are more uniform in appearance, and why the parts built afterwards appear more diverse. For example, in Paulet Road, built up before 1885, all the houses have the same facade, while in Calais Street, built up in the 1890s and 1900s, each house or pair of houses looks different (Figure 1.7). After 1885, rather than being based on a masterplan by Messrs Driver, designs of the individual houses came from the leaseholders themselves (Figure 1.8). Some of these designs were prepared by the builders if they had the skills. Some were prepared by architects or surveyors appointed by the

FIGURE 1.6,

Organisational flow charts during James Lewis Minet’s ownership 1839–85 (top) and William Minet’s ownership 1885–1932 (bottom). They summarise roles and relationships for the two major phases of the estate development.

FIGURE 1.7,

On Calais Street each house or pair of houses was custom-built to a different design and by different builders. No. 11, for example, the house in the middle, was built by the Cooperative Builders for WH Spragge, 1901.

FIGURE 1.8,

Drawing for house in Cormont Road, built by Peter Arundell and designed by Ernest Avery, ‘Architect & Surveyor’, c.1897.

leaseholder. While the architecture was evidently inspired by various sources, there is no evidence to suggest that the designs were copies of pattern book examples; instead the houses were generally custom-designed, even if their style and detailing relied heavily on inspirations from similar precedents.34

A letter of April 1904 from Fred Curtis to the builder and lessee Peter Arundell reflects the system for the second phase of the estate build-up under William Minet:

The majority of the houses on the estate were built by speculative builders constructing for an anticipated demand in response to which they would then sell them on or rent them out. Peter Arundell & Sons and Andrew McDowall & Son were the most prolific speculative house-builders on the estate after 1885. Peter Arundell & Sons constructed more than 50 houses there over a period of about twenty years, beginning in the late 1880s as a sub-lessee to Mayhew in Upstall Street; Andrew McDowall & Son constructed just over 90 houses, and one of the streets on the estate bears the name McDowall.36

However, some of the houses – those facing Myatt’s Fields Park along Calais Street and Cormont Road – were developed by owner-occupiers rather than by speculative builders. The system for those houses is explained in more detail in a letter of September 1901 from Fred Curtis to WJ White, a potential lessee and owner-occupier for 14 Calais Street:

Curtis’s letter also reveals that William Minet assisted leaseholders on occasions with finance to facilitate building work. Minet would advance the mortgage amount to the lessee so they had the funds for the construction of the house; once the house was built, the lessee could take out a mortgage against it and pay Minet back. It was a system that allowed him to keep his investments and risk low, but at the same time encouraged potential tenants to take on the leasehold and enabled them to build their own houses.

A centrepiece in the planning of the estate was the creation of Myatt’s Fields Park as part of the second phase of the estate development. William Minet donated the park to the newly formed London County Council (LCC) in 1889, soon after he inherited the estate.38 The park itself was designed by England’s first professional woman landscape gardener Fanny Rollo Wilkinson.39 While undoubtedly a generous, philanthropic gesture, Myatt’s Fields Park also became an important asset for the estate. It contributed significantly to establishing an attractive, leafy surrounding for the adjacent housing and helped to attract well-to-do tenants. This effect can be seen on the Booth maps of 1899 of the area, which show a particularly high concentration of wealthier tenants around the park.40 Although the houses facing the park were occupied by and probably intended for upper-middle class tenants, those planned after 1885 were generally in terraces rather than semi-detached or detached houses. Experience of earlier development had shown that smaller terraced housing was more quickly taken up by lessees than larger, more expensive detached and semi-detached houses.

Beyond its effect on its immediate surroundings, Myatt’s Fields Park was also important in linking the estate in character to the generously spaced, largely semi-detached, wealthier and more desirable area to the south-west, rather than the poorer area to the north-west. This link was reinforced in the layout of the new roads Brief Street, Calais Street and Cormont Road, which were approved by the LCC in 1891.41 Cormont Road and Brief Street are both orientated to the south-west, while avoiding as much as possible any links to the north-west. The only road connection to the north-west, the extension of Calais Street towards Lothian Road, was not part of the original layout and only added later, receiving approval from the LCC in 1893.42

The greener, more loosely planned later phase (after 1885) and the more rigidly planned earlier phase were also products of their time. By the late nineteenth century, the density and rigidity of Victorian speculative terraced housing – so-called by-law housing – was often blamed for poverty and squalor. Long before it became official town planning policy in the inter-war period, more green space around houses was a widely propagated solution to create healthier places in which to live. In 1865, for example, GL Saunders stated in a paper to the influential National Association for the Promotion of Social Science: ‘It is already clearly demonstrated that the more you pack the people together, the greater is the amount of disease and death.’43

Bedford Park, begun in 1875, was one of the first housing estates to give form to such ideas.44 While the Minet Estate could not be considered part of this architectural avant-garde, its planning after 1885 still seems to have been influenced by such ideas; the more spacious later phase of the estate, with generous vegetation and meandering roads, not only has similarities with the planning of the area south-west of the estate but also with the green and somewhat irregular layout of Bedford Park, which seems more than coincidental. William Minet was probably aware of Bedford Park and envisaged a similarly spacious, greener surrounding for the housing on his estate.

FIGURE 1.9,

Brief Street, built in the 1890s, showing the transition from houses to blocks of flats and the increase in density during the estate’s final development phase. The houses to the left were constructed by AB Gee. The block of flats to the right was by the Cooperative Builders.

Even if the urban design of the Minet Estate was not avant-garde, its planning was nevertheless clever and forward-thinking in many respects. One of these was its mixture of low-rise housing with blocks of flats, which was fairly unusual at the time. When available building sites became scarce, William Minet broke with the typically low-rise house building of the area and took a risk by commissioning the construction of five blocks of flats (Figure 1.9). The flats increased the overall density and gave Minet a higher rental income than from the land alone. At the same time, the area still retained a village-like quality, supported by Myatt’s Fields Park in the centre with mainly low-rise housing around it.

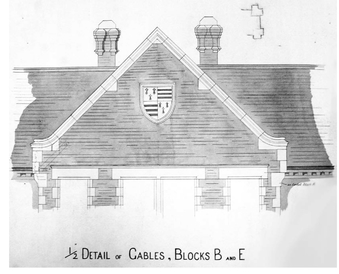

All the blocks of flats were built around the turn of the century: Burton House (1892), Calais Gate (1903), Orchard House (1897), Dover House (1899) and Hayes Court (1900). The blocks were generally well built with careful architectural detailing, which is particularly apparent in the Calais Gate building, which was constructed by the Cooperative Builders under the guidance and supervision of Fred Curtis (Figures 1.10–1.11).45 The attention to detail in the architecture of these buildings reflects the pride that William Minet took in every aspect of the estate: the signs of personal attachment are ubiquitous on the estate, which is full of references to Minet family history, ranging from family crests with a cat (referring to the French meaning of the word minet: ‘kitty'), to names of streets and buildings (Calais Street) and to family references in decorative stone mouldings (Calais Gate).

Unlike the houses, the flats were not sold on long leases of 99 years but were instead rented to tenants on annual leases.46 The blocks of flats also did not have the same degrees of customisation and adaptability of the houses built on the estate. Victorian and Edwardian blocks of flats were built with largely load-bearing walls, so subsequent changes have probably only been cosmetic apart from updates to building services and technology.

FIGURE 1.10,

Calais Gate, built 1903. One of the blocks of flats built on the Minet Estate in the last phase of its development.

FIGURE 1.11,

Detail drawing for Calais Gate, 1903.

Conclusions and Lessons from the Minet Estate

A perhaps all too obvious but key conclusion from this case study is that it was indeed planned. The housing was not somehow generated through by-laws and pattern books: it was actively planned and designed, and its development managed, at times with a high degree of sophistication – reflected, for example, in the Parsons & Bamford lease agreement. Formal planning tools were used, mainly building or lease agreements, drawings and specifications. Various stakeholders – landowners, estate surveyors and agents, builders and architects – played key roles at different stages of this process.

And the estate was also planned in that its arrangement and layout were carefully considered. As has been shown, the roads, green spaces, types and sizes of housing were deliberately laid out to respond to their surroundings and also to market conditions of the time. This process itself was, of course, not always linear and often driven as much by commercial considerations as by architectural ones.

Overall, the considered planning and management of the development was an important reason for the success and quality of the housing on the estate to which William Minet contributed considerably during his ownership. His intentions were not simply to create as many houses as quickly as possible, but instead he took a long-term view of the impact of his decisions.

The contrast between the earlier development phase under James Lewis Minet and the later phase under William Minet is striking, and is only partly due to the changing architectural preferences of the time. As outlined above, the nature of the lease agreements with the builders had an important impact on the architecture. In the earlier stages of development before 1885, the design was prepared by the freeholder’s agent, the estate surveyor, and imposed on the lessees. In the later phase after 1885, the main responsibility for design was with the leaseholder, and the freeholder only approved it. This duality can also be related to other speculative housing in London. Any speculative housing estate in the nineteenth century that was consciously planned would have had to adopt one of these two extremes – either the design was led by the estate owner or it was led by the builder of the individual houses.

The Minet Estate case study also shows that Victorian and Edwardian estate planning could support degrees of diversity, customisation and adaptability in its architecture. These qualities were not accidental but part of the original conception of the buildings, and they continue to contribute to the houses’ desirability today. The structure or framework for this openness was the simple layout of building plots along roads. Customisation was driven by the leaseholders who built and often also occupied the houses; coherence in the architecture was achieved either by controlling street elevations or by a process of approval from the estate owner or agent.

In terms of potential lessons for London today, it would be naive and also undesirable to propose that the positive qualities of the Minet Estate’s development could simply be transplanted into the present to provide easy answers to current issues. There are, however, aspects of Victorian house building as shown in this case study, that could provide inspiration for housing today. One key aspect is that the development allowed for and promoted diversity in its architecture and stakeholders, which was supported by the leasehold development system and financing model, as well as in a simple yet responsive development control framework. It is conceivable, for example, that a local authority could procure a similarly coherent, but individually diverse estate like the Minet Estate today using custom builders and Local Development Orders. Custom-build developments in the Netherlands, such as those in Amsterdam and Almere, as well as Graven Hill in the UK, could be cited as successful precedents with many similarities.47 Certain aspects of the Minet Estate’s development were controlled, while others were left to those who occupied and built the houses, which helped to facilitate a degree of openness to future user adaptations and changes. This approach could provide inspiration for today’s planning system in England. The design of the buildings on the Minet Estate simply complied with the Building Acts and was coordinated by an estate surveyor and agent. The Minet Estate could therefore be built up without lengthy planning negotiations, which today can often take years even for small buildings in London, further adding to the unaffordability of housing. It is conceivable that today’s planning process could be simplified for particular developments, making a swifter, more predictable decision process possible again.48

Another aspect of the Minet Estate’s development and Victorian housing that could provide ideas for addressing today’s housing affordability crisis is the financing. More than construction costs, a significant barrier to custom- and self-build today is prohibitively high land costs. Any attempt to involve more small-house builders, as well as custom- and self- builders with low capital like first-time buyers, would need to address this barrier of high land costs and find ways to lower the financial entry threshold. On the Minet Estate this happened through the leasehold system. The price for the land was nil initially, but then a ground rent was charged over a 99-year period. In some cases, William Minet even provided a loan to help with construction costs (as reflected in the letter above from Fred Curtis to WJ White).

For example, one way of lowering this financial threshold could be to offer suitable sites – such as those owned by local councils or philanthropic landowners – to custom- and self-builders at an affordable initial cost as leaseholds; the lessees would then be responsible for the design and building of the houses. The initial purchasing cost for the land could be kept low by transferring it to affordable annual ground rents. Land that can be rented at secure ground rents would significantly lower the threshold for house building and make initiatives such as custom- and self-build accessible to a much larger part of the population.49 Such a leasehold development system could be profitable for both the landowner and the leaseholder who builds the housing. This idea may sound like fiction in the current market, but one does not need to look far to see that it is feasible: a similar model, the so-called Erfpacht system, has been successfully employed on a large scale in the Netherlands, making custom-build an affordable and real option.50

These are some suggestions drawn out of the case study of the Minet Estate; there may be others. The crucial point seems to be this: the Minet Estate shows that diversity in scale, stakeholders and architecture was possible then, creating a lasting, adaptable and attractive built environment. If the Victorians could do it, why can’t we?