Chapter Eleven

Lessons of the Past for My Architectural Practice

SIMON HUDSPITH

There is something very concerning about the recent race for numbers. It seems that whoever you speak to – whether a local councillor concerned about the lack of affordable housing, a planner wondering how on earth we are going to meet the housing targets, or a commercial ‘house builder’ thinking site value, speed and profit – the conversations eventually sound the same: ‘How many and how quickly?’ What is more alarming is the way in which this mantra has become part of a collective subconscious, distorting our judgments and our decisions about how we should live. Throughout London and the south-east the results of this attitude, while initially manifest as quotas or targets, are now being delivered at an alarming rate. ‘Denser, higher, quicker’ is reshaping our built environment beyond any domestic recognition, and the race for numbers has become the default justification for politicians, property developers and planning departments. Standardisation and repetition are synonymous with faster and cheaper which, when translated into residential buildings, results in the systematised planning of living space and the mass production of the building components that enclose it. Homes become units, and the more they are stacked both horizontally and vertically, the more can be fitted onto the land on which they stand. If materials and components are the same, then the buildings are cheaper and quicker to construct. When ten becomes 100 and 100 becomes 1,000, the relentless uniformity results in anonymity and ultimately the loss of identity. Which is my house? Where do I live? The very values of place and home are being lost.

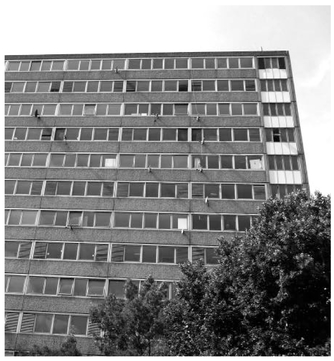

The race for numbers, however, is not a new phenomenon. The very same issues existed in post-war Britain where the demand for housing married perfectly with the Modernist movement and the need to build cheaply and quickly. Discussed in the 1950s, built in the 1960s, and inhabited in the 1970s, projects had similar justifications and of course very similar results. The slab blocks of the 1960s and 1970s were the prefabricated winning formula, realised with great pride in almost every major city in the country. After only a decade or so, however, the solution to the numbers problem was showing signs of social failure, and was eventually considered to be an insoluble problem to which it seemed the only answer was to move out, demolish and start again. The costs are catastrophic and no local authority has the appetite – or even dares – to quantify what this figure really is. Instead, the removal of council estates is now a key part of urban regeneration as it aligns perfectly with the race for numbers in that it provides an opportunity for densities to be increased (Figure 11.1). In the past, however, there have been countless instances where increased densities have been addressed by communities with very simple technologies, limited resources and challenging living conditions.

FIGURE 11.1,

Aylesbury Estate, 1963–1977, currently being redeveloped.

FIGURE 11.2,

Mansion flats of the 1890s on Prince of Wales Drive, Battersea.

During the Italian Renaissance, Florence, Verona and Venice all expanded rapidly yet maintained a sense of community. In seventeenth-century Amsterdam, economic growth pushed the city to create the new community of Jordaan to house the increasing numbers of working-class and immigrant people. And in late nineteenth-century London, high-density elegant mansion blocks were built in Battersea, Maida Vale and Knightsbridge, with clear identity and character to accommodate changing demographics and rapid population growth. Although these examples were expressed through different architectural styles and made from different materials, they have one thing in common – a collective sense of community that is identifiable and allows each generation to feel ‘part of’ and to ‘contribute to’ this community (Figure 11.2).

As an architect, I have worked for much of my career in medieval and historic towns, observing and trying to understand why they have such integrity, with communities having developed over hundreds of years, and why each generation maintains a strong affinity with the place. So, when confronted with our first high-density housing project, my instinct was to look more closely at these historic examples rather than many of the principles of contemporary housing defined in the theories of the Modern Movement and built during the second half of the twentieth century.

The first question is ‘Where do I live?’ – or, more importantly, ‘Where is my home?’ In any city, and particularly a large city like London, the answer is more often than not the name of a part of the town or what used to be a village before they all joined up: Camden, Maida Vale, Islington, Brixton, Clapham, Dulwich and many more (Figures 11.3 and 4). This is important not just for location purposes; what seems much more important is the type of community that exists within these places, and the established strength of this community, whether you grew up there or moved there as an outsider. Some communities have existed for centuries and others for a handful of generations; in either case, however, they are reliant on the time it takes for members of these communities to contribute in a way that makes a difference. These contributions or differences then build on each other, becoming readable through what is built or changed. When successful, this is reinforced over time, each generation contributing something new while at the same time reinforcing the values of the existing community. Whether this takes 20 years or 200, the time factor for the expression of the community is crucial to its success.

FIGURE 11.3,

Brailsford Road, Tulse Hill, terraces of the 1880s with unusual and varying rooflines.

FIGURE 11.4,

Carlton Avenue, Dulwich Village. Variation and repetition in semi-detached houses.

The challenge of contemporary residential developments is that they are immediate, with large numbers of residents taking occupation in very short periods of time. There is no time for a community to develop, for the individual to make their mark or respond to the contributions of others. To counter this problem, by expressing buildings as a collection – or as groups of homes rather than as a unified block – inherently suggests that there might be a ‘coming together’ rather than an imposed system. It also suggests that there may be an opportunity for differences within the group. The concept of the group, by its very nature, is synonymous with the idea of community, as it relates directly to our own experiences and understanding of the ‘family’, and in turn is how groups of families might underpin the idea of community. In practical terms, this could manifest itself as repeated similar, but not identical, forms, or a single material that may vary in colour or texture or be assembled in a slightly different configuration.

The idea of group also suggests that there is an opportunity to accommodate differences. This raises the next key need: the expression of the individual within a community. In historic terms, this expression probably starts with the vernacular, which in its simplest form grows out of an understanding of working with readily available materials, but then technically develops over time to produce quite sophisticated techniques for building. During this process each generation or individual interprets the principles in a slightly different way, which in turn creates a natural variation or an individual expression within a common set of rules. This same principle seems to apply across the skill set. Whether through self-builders or master builders (medieval to eighteenth century) or through the relatively recent emergence of the architect as designer: individual expression within a common set of rules is a building block for establishing communities.

Jordaan is a glorious example. The principal building form of the houses is repeated through plot facades of three to six storeys, primarily made from brick with pitched gables, and with wooden window frames often lined in stucco or stone. The place has intensely powerful collections of buildings producing infinite variety that at the same time allow individual expression to be an integral part of the community. Subsequent generations immediately relate to this – not just builders, but also as buyers, primarily because it answers the two fundamental questions, ‘Where do I live?’ (‘In this identifiable strong community’) and ‘Which is my home?’ (‘The house with the brown bricks and tall windows, next to the one with blue bricks. ’) A century later, Georgian architects in Britain were applying a more controlled approach to the same principles. And despite the common view that what is great about Georgian architecture is its consistency, the great squares of London are full of subtle differences within a common language (Figure 11.5).

FIGURE 11.5,

Camberwell Grove Conservation Area houses a variety of eras and architectural expression.

FIGURE 11.6,

Criffel Avenue, Streatham. Elaborate features on a corner detached house.

Another century on and the Victorians were rolling out mass housing across London. They used very similar house plans and the houses were almost exclusively made from London stock bricks and red bricks, and elaborated with bay windows and gables. The streets are the basis of the community and, although the consistent language creates uniformity, there are endless subtle differences to give the individual a sense that their home is unique. Rarely is there more than a handful of houses exactly the same. When combined with the opportunity of individual expression through front doors gates and gardens, each house is unique (Figure 11.6).

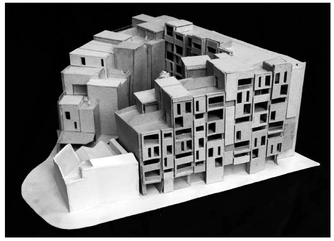

During the early design stages of our first high-density housing scheme in Bear Lane, Southwark, about 10 years ago, I was not consciously thinking of these principles in the way I have described above. Ideas were collected from a number of different sources, including Italian hill towns, the Giants’ Causeway, and even 1960s housing developments, and explored through a series of sketches and models at various scales, then gradually refined into a final design. Subconsciously, however, those two questions ‘Where do I live?’ and ‘Which is my house?’ were guiding many of the ideas and subsequent decisions. The principles that emerged were: a group of townhouses clustered around a courtyard, responding both to the constraints of the site and more importantly to their neighbours, as members of a community; facades that express each house with subtle change in size, recess and projection, suggesting that they may have been built at different times by different people; the use of a vernacular language of brickwork, present in the warehouses that previously existed and were prevalent building types in the area; windows expressive of hierarchy within each facade so that bedrooms, kitchen and living rooms have a relative importance and work around an inset and primarily private balcony that engages with the primary living spaces; varied colours of brick and window configuration with details that don’t quite make sense, alluding to the idea that these buildings could have developed over time and that every home is unique (Figures 11.7 and 8).

FIGURE 11.7,

Bear Lane, Panter Hudspith Architects, completed 2009, stacked multi-storey forms contort the reality of single-storey flat planning inside.

FIGURE 11.8,

Design model for Bear Lane. Architecture divides building volume into distinct bays with unique frontages.

Following shortly after Bear Lane, Royal Road was another high-density residential scheme comprising 96 affordable homes near Kennington Park in South London. This project was the result of a competition run by Southwark Council to re-house residents from the Heygate Estate, which was about to be demolished as part of the regeneration of the Elephant and Castle area. The Heygate Estate was in many ways the quintessential 1960s slab block, with all of the associated problems, and the subject of great debate on the relative benefits of urban renewal through demolition – especially in relation to the loss of affordable housing numbers on the site. For us, it was the perfect opportunity to see if a new community could be created that embodied many of the ideas that had been explored at Bear Lane, and hopefully to raise the bar for the standard of affordable housing. It was also an opportunity to further develop a clearer understanding of how ‘Where do I live?’ and ‘Which is my house?’ could inform our design.

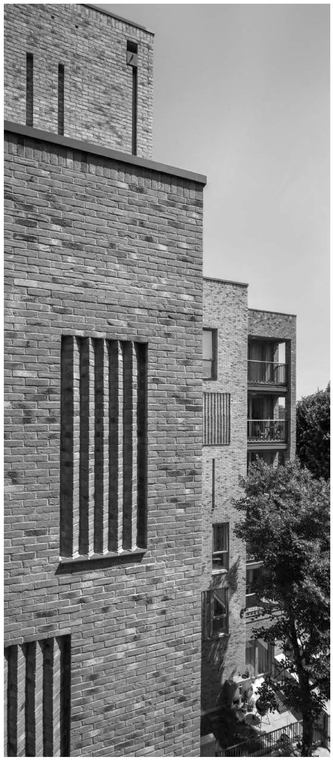

Luckily there was a group of mature trees around the periphery of the site that helped establish an immediate character and setting. In trying to keep as many of these trees as possible, we pulled the mass of the building back from the edge of the site, with a core at each corner centred on a cruciform plan with radial apartments projecting in each direction. The circulation space is covered, although open to the elements to allow the free movement of air and long views to the surrounding area. Each apartment has its own front door and is detached from its neighbours, providing a triple-aspect living room with views over the retained mature trees (Figures 11.9 and 10).

On the east and west sides of the scheme, the cores are then linked with a series of four-and five-storey ‘town houses’, again with their own front doors, that complete the enclosure to a central communal courtyard which is the heart of the community. Three-and four-bedroom maisonettes with front and back gardens occupy the lower storeys, while the upper floors are connected by individual bridges from each of the four cores. At the top of the building the stepping of blocks provides a roof terrace for the apartment above and at the very top of each core there are three-bedroom maisonettes with roof gardens over the apartment below. Although there was some repetition of apartment plans on the middle floors, the need to make every apartment unique was still central to designing the architecture.

FIGURE 11.9,

Royal Road, Panter Hudspith Architects, completed 2013. Divided into distinct blocks with articulated elevations.

As at Bear Lane, two similar tones of bricks were used, although – instead of shifting the planes of the facade – this time the masonry was carved into, using ‘saw-tooth’ brickwork. A set of simple rules was established for how the saw-tooth brickwork could amplify the more important windows, or suggest that windows may have once existed but had subsequently been blocked up. Each of the three architects working on the project was asked to design various parts of the elevations using these rules, although they worked in semi-isolation. This created a natural variation within a given language, alluding to the idea of a community changing over time with each generation contributing something slightly different and making the elevation of each apartment unique. The design aims to support this important sentiment among residents to be able to say: ‘This is my home!’

FIGURE 11.10,

Royal Road. Articulated elevations create unique frontages for each of the 96 homes in the development.

I would not begin to claim that the ideas we have explored in Bear Lane and Royal Road are solutions to the problems that I have identified in the high-density housing of the 1960s and its current resurgence in the race for numbers. Nor do they begin to have the equivalent vitality and deep-rooted sense of community and identity that exists within our historic towns and cities – that can only develop over time. I do hope, however, that these example projects are built examples responding to the questions of ‘Where do I live?’ and ‘Which is my house?’ And I hope they show that affording a little more thought and sensitivity to the design of our housing could help to make a new building feel less anonymous and more like a home – a place that is identifiably unique but also part of a local community.