Chapter Eight

‘We Felt Magnificent Being up There’ – Ernő Goldfinger's Balfron Tower and the Campaign to Keep It Public

DAVID ROBERTS

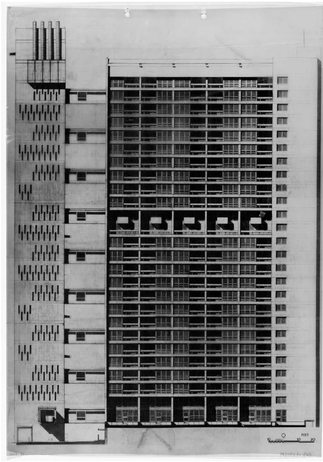

In December 2015, the London Borough of Tower Hamlets approved plans to refurbish and privatise Balfron Tower, a high-rise of 146 flats and maisonettes arranged on 26 storeys built in 1965–7, the first phase of émigré architect Ernő Goldfinger’s work on the Greater London Council’s (GLC) Brownfield Estate in Poplar, east London (Figure 8.1).

In this chapter, I describe my collaborative work with the tower’s current and former residents in the preceding three years, during which we campaigned for Balfron to remain a beacon for social housing. I structure the chapter on the three phases this work followed: an analysis of cultural, academic and archival material, which foregrounds both the persistent accusations of failure that have afflicted the tower and the egalitarian principles integral to its vision and function as social housing; engagement with residents, re-enacting Goldfinger’s own methods of gathering empirical evidence in 1968; and activism drawing on this material and evidence to contribute to a more informed public debate and planning decisions. Through this chapter, I illustrate how Balfron’s history was mobilised to commodify the tower on the one hand, and to interrogate and object to this process on the other. In doing so, I advance an argument that the practice and guidance of heritage of post-war housing estates must not only pay tribute to the egalitarian principles at their foundations, it must enact them.

‘Out of Touch?’: Analysis of Cultural, Academic and Archival Material

Throughout the shifting course of opinion, both popular and expert, certain judgments of Balfron Tower have been accepted uncritically – correlating its architecture of dramatic proportions with a way of life as stark and severe, ill-suited to the needs of families, and at a high density in which socialisation is difficult – prompting one politician to declare it ‘the benchmark of post-war architectural failure’ and a regeneration manager to recommend ‘this and all its ilk should be demolished and consigned to the bin marked “failed experiment’’‘.1

In a paper to the Courtauld Institute 20 years ago, historian Adrian Forty reflected on some of the reasons why the architecture of the post-war period absorbs our interest, and some of the things that stand in the way of our understanding.2 He noted the first, and most awkward, fact faced by the historian is that it is widely considered a failure. This label of failure, he observed, is reserved

FIGURE 8.1,

Balfron Tower, 1971.

almost exclusively for works built by the state, and, most commonly, in reference to social housing schemes. Forty suggested the mistake historians have made is to look in the wrong place for the causes of failure. With very detailed historical attention they have vindicated the architects or buildings themselves by stressing their aesthetic qualities and honourable intentions, though, in doing so, they often overlook social issues or propose causal explanations for their failure on technical or cultural grounds. Instead, Forty offered, it would be better to ‘examine the minds of those who judge these works’.3 We should not, he said, be troubled by whether or not they actually were a failure but that they have been perceived to be.4

I wish to take on Forty’s thorny epistemological and methodological challenge of perception in relation to Balfron Tower. I speculate that most people have not taken the opportunity to visit and gain direct experience of the tower, so how else might they have arrived at the damning conclusion of failure? To answer this, I briefly consider the body of cultural material that broadcasts a certain perception of the tower to the public.

The most famous representations of Balfron Tower are in feature films which go beyond the typical kitchen sink dramas set in housing estates to fictive dystopian wastelands. In Danny Boyle’s harrowing sci-fi horror 28 Days Later, a virus has spread to humans turning them into ‘the infected’, frothing zombies that scale the tower in vicious bands.5 In Elliott Lester’s crime thriller Blitz, Balfron stars as the home of a strutting psychotic serial killer who murders members of the police force.6 Paul Anderson’s Shopping is set in the tower block and follows its gang of feral teenage residents who indulge in joyriding and ram-raiding.7 These films, and countless others, use Balfron as a backdrop for invariably frightening incidents in which the tower appears from acute angles, its warm aggregate stained under filters. They exploit Balfron’s height and style as inherently unsafe and violent, and embellish its neglect, both material and social, by dressing the tower in graffiti and abandoned cars. This is reinforced in the accompanying dialogue: ‘Look at this place, how do people live in this filth? ... This whole estate’s a disgrace.’8 Ben Campkin has characterised this powerful imaginary of decline that has encircled post-war estates and distorted our understanding, ‘taking them into a representational realm of abstract generalisation’.9 Campkin explores this characterisation further here in Chapter Nine.

This is a reading echoed in newspaper reports. In 2014–15, The Mirror described the building as ‘attracting muggers, drug gangs and junkies and rumoured to once be the local council’s go-to solution for problem tenants’;10 Time Out portrayed ‘junkies in the stairwells, domestic violence, drug deals and constant low-level crime’;11 and the Daily Mail summarised Balfron as ‘known for violence, crime and poverty’.12 This is taken even further by the Sunday Times, which identified it as ‘the ugliest building in London’, by LBC radio as the ‘worst eyesore in London’, and upgraded still by The Mirror and Evening Standard who anointed it ‘Britain’s ugliest building’.13 We must question where the evidence for these claims lies. One possible explanation is simply the style it has come to symbolise – its categorisation as a ‘leading example of so-called Brutalist architecture’.14 In 2000, Simon Jenkins in The Times wrote:

The term ‘Brutalism’ was coined by architects Alison and Peter Smithson and theorised by critic Reyner Banham after the French word ‘brut’, referring to the uncompromising use of raw concrete that figured boldly in abstract geometries of late Modernist buildings.16 Goldfinger’s use of bush-hammered concrete and the dramatic style of his designs mean that they are often categorised as Brutalist yet, like many of his contemporaries, he never used, and actively disliked the term. In cultural and media representations like Jenkins’, Brutalism is most commonly used as an intentional conflation of an architectural style and the brutal behaviour that takes place within it. Ike Ijeh in Building wrote:

Alongside the aesthetic condemnation, Ijeh’s insinuation of structural failings is repeated by many other commentators; The Mirror describes it as ‘decayed’, The Evening Standard as ‘asbestos-ridden’ and The Guardian as ‘decaying’ and a ‘crumbling obelisk’.18 These representations amass to create an image of violent intent and material decay, both physical and, by inference, social. Finally, the Architects’ Journal describes the tower as ‘an impenetrable fortress’ in which flats are ‘clad with penitentiary steel bars’,19 and The Mirror depicts Balfron as ‘the kind of place where people rush past with their heads bowed, terrified of making eye contact with their unknown neighbours’. As performance theorists Charlotte Bell and Katie Beswick have noted elsewhere, it makes us, as viewers, speculate in the popular belief that there is ‘a correlative relationship between the council estate environment and “pathological” behaviour of estate residents’ – in this case an architectural determinism so extreme that a brutal building might even breed brutal murderers.20

These images of Balfron Tower have a much less firm place in popular culture than those of its creator. By accident of a bizarre set of circumstances that brought his exotic name to the attention of James Bond author Ian Fleming, Goldfinger is fated to exist as much in fiction as in flesh and blood.21 Indeed, almost every article repeats the trite contention that he provided the inspiration for Fleming’s villain. As the Architects’ Journal has noted, ‘a large part of Goldfinger’s iconic status rests on his name itself, with all its bizarrely descriptive resonance and its filmic associations with evil desires for world dominance’.22 The other part of Goldfinger’s iconic status rests on his forceful personality – a lifelong Marxist with an unmistakable Hungarian accent and famously explosive temperament. When combined, it seems difficult for those depicting the tower to avoid what Michael Freeden has labelled the ‘individualistic fallacy’ which ‘overstresses the function of a particular individual as the creator of a system’.23 In this, it is commonplace for the trope of hero or villain to shape and dominate the discussion. Those inclined to read the story of Balfron Tower as a morality play of tyrannical hubris exaggerate both the intentions of Goldfinger’s architecture and its lived actualities without evidence. The most common conception assumes Goldfinger’s aim was to deliver utopia for its residents – an aim so unachievably high that anything less than the perfect society means failure. In this narrative arc, following the fall from utopia to dystopia, Goldfinger the hero is transformed into Goldfinger the villain. This gives rise to pathetic fallacy in which the architect is his building; Goldfinger, the supercilious or well-intentioned social engineer comes to look like his creation – a terrifying, flawed, tower of a man.

As I discovered further such representations, I came to realise how easy it is to be seduced by this dominating story; to conflate, without any available evidence to the contrary, these perceived experiences for lived ones and assume tenants have been clamouring to escape. Having dwelt in the speculative and the fictional, I too wish to escape, leaving behind the sofa strewn with popcorn kernels to enter the civilised academic spaces of the library and archive. Looking across the literature I gather on the tower, I identify a recent proliferation of accounts with a resurgence of interest in Balfron’s quality, ideals, and social history.

The first trend is a renewed appreciation by historians and critics of the quality and originality of the tower. Andrew Higgott describes a new climate in which ‘once disdained modern buildings such as the housing tower blocks by Goldfinger are now valued, not as curiosities, but as good architecture’.24 Kenneth Powell declares, ‘Aesthetically, London’s best high modern buildings are the two strange housing towers by that tough-minded disciple of Auguste Perret, the late Ernő Goldfinger’.25 Andrew Saint and Elain Harwood cheer these ‘extraordinary’ towers as ‘isolated statements of French monumentalism and concrete technique in the unexpected settings of North Kensington and Poplar’.26 Bridget Cherry recognises ‘superior quality is at once apparent’ when approaching Balfron: ‘The 26-storey block is immediately arresting, with its slender semi-detached tower containing lift, services, and chunky oversailing boiler house’.27 Alan Powers’ lecture to the Royal Academy offered his audience an experiential account of the tower, in which he describes Balfron’s architecture as neither alien nor imposed but well suited to its post-industrial landscape; it ‘is a wonderful landmark, you really know where you are in East London when you see this, it does matter’.28 Similarly, on his ‘walk around Poplar’ a few years later, Owen Hatherley sees Balfron rising vertiginously, ‘animating its attempt to protect residents from the din and ugliness of the Blackwall approach’: its ‘flats are large and simple, the bared concrete is beautiful, detailed with a craftsman’s obsessiveness, the communal areas largely make sense, and the buildings have an impressive sense of order and controlled drama’.29 For these reasons Balfron is selected alongside Trellick Tower, its sister tower by Goldfinger in west London, in Hilary French’s global survey of Key Urban Housing of the Twentieth Century.30

It is notable how many of these accounts reiterate the scholarship and emotional charge of two articles in 1983 by James Dunnett, a former employee of Goldfinger, which still comprise the most definitive texts on Balfron Tower to date. It is worth quoting at length from Dunnett’s prologue to his first article, in which he argues it is time to take Goldfinger’s work seriously:

FIGURE 8.2,

Balfron Tower, west elevation, 1965.

In this, Dunnett uses oxymoron and metaphors as stark and dramatic as the architectural language of the building to advance an intellectual case intended not only to introduce us to Goldfinger’s buildings but to introduce Goldfinger to the architectural canon. In his companion Architectural Review piece, Dunnett develops Goldfinger’s adherence to the moral and aesthetic tenets of the Modern Movement,32 describing Balfron’s design as ‘a highly original synthesis’. In plan and section, the dual aspect flats served by an enclosed access gallery every third floor are a ‘new’ and ‘satisfying’ response to strict LCC briefs; in elevation, the rhythm of windows, slabs and crosswalls is ‘of profound harmony’, connected by access galleries that ‘resemble a row of railway carriages’ to the detached circulation tower set ‘emphatically to one side’ which Dunnett calls ‘perhaps Goldfinger’s most expressive invention’ (Figure 8.2).

This work was cited heavily by English Heritage a decade later in a spot listing instigated by a resident to interrupt the Department of Transport’s plans to replace Balfron’s windows on the east façade because of the Highways Agency’s road-widening of the Blackwall Tunnel approach. Their listing description provides a straightforward account of the arrangement, design and detailing of the tower; offering brief moments of praise for Balfron’s ‘unusually well thought-out’ internal finishes, the ‘distinctive profile that sets it apart from other tall blocks’, and that, ‘more importantly, it proved that such blocks could be well planned and beautifully finished, revealing Goldfinger as a master in the production of finely textured and long-lasting concrete masses’.33

The second trend across these academic accounts measures Balfron against currently held urban ideals today. Conservation specialist Martin O’Rourke’s chapter in Preserving Post-War Heritage (2001) describes how the ‘wave of optimism that characterised the post-war period of fifty years ago is difficult to appreciate in our more guarded and cynical times. It was an era when market forces and spending limits counted for less than social cohesion and better living standards for all.’34 He advocates revisiting ‘earlier modern attempts to reshape the city’ which serve as ‘inspirational beacons against which to test our own feeble attempts at a robust celebration of urbanism’, citing ‘Balfron Tower and its attendant building group’ specifically as they ‘constitute a major achievement of full-blooded modern architecture in the post-war period. It demonstrates that a social housing programme can be achieved with dramatic and high-quality architecture.’ In his entry on the Brownfield Estate to a 2013 Design Museum exhibition, Lesser Known Architecture, Owen Hatherley agrees: ‘These pieces of inner city architectural sculpture are fragments of a better, more egalitarian and more fearless kind of city than the ones we actually live in.’35

Perhaps because of this, the third trend to observe from this scholarship is a desire to piece together Balfron’s social history and the social elements in its design.In his biography Ernő Goldfinger: The Life of an Architect, the philosopher Nigel Warburton quotes some of Balfron’s original inhabitants and reappraises the ‘sociological experiment’ of 1968 in which Goldfinger and his wife Ursula moved to a flat at the top of the tower for its opening two months to diligently gather empirical knowledge.36 Warburton sees this as not only ‘a public commitment to the virtues of high-rise living’ but an opportunity ‘to give a far more informed opinion of the benefits and problems when he had experienced them himself’. In her article for the Twentieth Century Society, historian Ruth Oldham mines the archives further and transcribes Ursula Goldfinger’s diary notes from their stay, concluding an ‘overall feeling one gets is of great support for this huge experimental building that her husband has built, and of absolute conviction that they should learn as much as they can from it’.37

Before concluding on these three academic trends, I wish to turn to Goldfinger’s exceptionally thorough archive, bequeathed to the RIBA upon his death, from which we can build a fuller picture of this ‘sociological experiment’.38 Goldfinger requested privately to live in the block from February to April 1968 to document and assess his designs for high-rise living. Under Housing Committee Chairman Horace Cutler, the GLC accepted and elected to generate publicity around this. At Balfron Tower’s completion in 1968, Goldfinger, not averse to a bit of publicity, informed the assembled group of national and international reporters that he wished to ‘experience, at first-hand, the size of the rooms, the amenities provided, the time it takes to obtain a lift, the amount of wind whistling around the tower, and any problems which might arise from my designs so that I can correct them in the future’ (Figure 8.3).39

Dozens of widely supportive articles quote Goldfinger’s pitch for high-rise living enthusiastically: ‘After six days of life high above the East End, Mr Goldfinger said: “I am enjoying this no end. I would love to live here”’.40

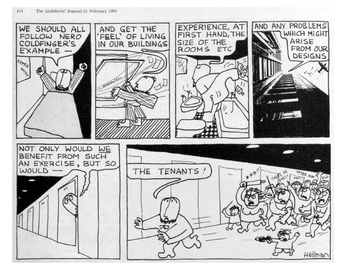

FIGURE 8.3,

Ernő Goldfinger, Desmond Plummer and Horace Cutler at the beginning of the Goldfingers’ sociological experiment, 1968.

A few days later, he told a different reporter: ‘I have created here nine separate streets on nine different levels, all with their own rows of front doors. A community spirit is still possible even in these tall blocks, and any criticism that it isn’t is just rubbish.’41 In these articles, it is most revealing how little the building is mentioned. For the national and architectural press, the drama is instead in the Goldfingers’ eight-week stay, treated with varying measures of amusement and admiration (Figure 8.4). After laughs have subsided, an earnest (but brief ) debate emerges in the editorial pages of the architectural press. One article, entitled ‘Out of Touch,’ muses on the nature of design and the relationship between built environment professionals and their users:

These press articles were collected fastidiously by Goldfinger, cut out and compiled into hardback notebooks available to view alongside private letters, notebooks and receipts (Figure 8.5). When he is not addressing reporters or conducting interviews for the BBC, Ernő Goldfinger attends an array of meetings including with the Tenants’ Association and composes letters in response to sincere queries from members of the public who have contacted him following the news reports. Ursula Goldfinger fastidiously writes a diary which concentrates on the day to day use of the building: whether doors can be opened while pushing a pram, where to store things.43 As well as productively dividing their time, the Goldfingers visit other flats together, recording encounters with those expressing delight at their new homes, as well as famously inviting tenants floor-by-floor to their penthouse for champagne parties where they mingled with notepads, collating opinions on the new homes in order to document and remedy design issues.

FIGURE 8.4,

Louis Hellman cartoon, Architects’ Journal, 21 February 1968.

The records reveal a balance of praise and criticism through observation and conversation with other residents, establishing a strong relationship with residents (who make Goldfinger an honorary member of the Tenants’ Association). The Goldfingers take the building and residents as evidence, conducting far more work than they have ever been given credit for in decades of accounts since, and demonstrating an empirical conviction to their endeavour.

Based on his experiences and residents’ feedback, Goldfinger wrote a report for the GLC dismissing any design issues and organisational difficulties as ‘trivial’ and concluding, ‘On the whole, the general disposition of the buildings and the flats are acceptable. I am prepared to repeat the same design in future schemes.’44 The only time he strays from unadorned observation is when he sets out how to improve communal areas: ‘For teenagers, rooms have been built in the service tower, away from the dwellings for: a) table tennis and/or billiards. b) jazz/pop room. c) hobby room, which can also be used for older people.’ In this description, lifted from ideas in Ursula Goldfinger’s diary, he picks out the spaces and social facilities provided for different age groups, explicitly aligning the form of the circulation tower and the podium in front to the communal activity he wishes to take place there. He places social considerations at the heart of his report:

Fifteen years later, Goldfinger was to bring up the human factor again in a brief interview.46 ‘Of course,’ he replied when asked if he would design his two high-rise housing schemes in the same way again, and proceeded:

- Rehousing is done in a haphazard way. For instance, so called “problem families” are dumped into unfamiliar surroundings, saddled with rents they cannot afford and are given practically no help to adjust

- Maintenance is lamentable

- Supervision is inadequate, incompetent and spiteful

- Vandalism is practically encouraged by persons who are antagonistic to this sort of development

- Tenants who are satisfied just let it be … only those who are dissatisfied complain

- The only complaint I came across – when living on the top floor of one of the buildings I designed and when I had my office at the foot of another for three years – was high rent’.47

These were to be Goldfinger’s last words on Balfron Tower before his death four years later. He could not have imagined the resurgence of admiration and popularity of his towers. His irate and combative response testifies to the hostility with which the public regarded tower blocks. From this we can conclude two points.

The first concerns the importance of this body of scholarship. The vast majority of academic accounts addressing Balfron Tower appeared well after the listing decision in 1996, a time in which post-war high-rises were still very much out of favour. It was Dunnett’s rigorous writings and sustained campaigning against popular opinion in the preceding decades that helped build the case for Balfron to be recognised by English Heritage. Other work since has validated this case and enriched Dunnett’s work. Although academic recognition is by no means enough to sway political agendas, as exemplified by the fate of Alison and Peter Smithson’s neighbouring Robin Hood Gardens (soon to be demolished), such work remains necessary as it is the foundation for any re-evaluation to occur.

The second point concerns what is missing from these accounts. In decades of scholarship on Balfron Tower, the tower’s residents – once the object and focus of Goldfinger’s research on the tower – have been overlooked. This omission is important. It does not make these accounts invalid, but it does make them incomplete. Scholars can justly claim the tower’s distinction compared with the environmental and technical deficiencies that have afflicted other high-rise blocks, but without consulting successive generations of residents and engaging in discussions on Balfron’s social life, persistent accusations of social suitability remain unaddressed. The perception of failure that Forty observed in public opinion of post-war architecture still haunts the tower.

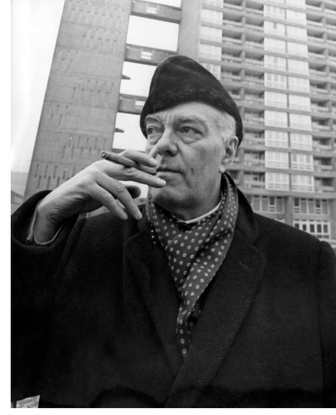

FIGURE 8.5,

Ernő Goldfinger, 1968.

‘It Opened up a New World to Me’: Engagement with Balfron's Current and Former Residents

In 2013, halfway into my doctoral research on another east London housing estate, I was invited by Balfron Tower resident Felicity Davies to assist her in conducting an oral history project as her neighbours were leaving their homes to make way for refurbishment works. The refurbishment was part of an urban regeneration scheme that had begun in 2008 following stock transfer of the public housing estate from Tower Hamlets Borough Council to Poplar Housing and Regeneration Community Association (HARCA). The public focus and funding that accompanied preparations for the London 2012 Olympic Games was the catalyst for a regeneration vision for the borough which aimed to refurbish properties to Decent Homes standards, improve public spaces and add new affordable and private homes to create ‘mixed-communities’. The plans detailed that approximately half of Balfron Tower’s 146 dwellings would be sold to cross-subsidise the costly refurbishment of a Grade II listed building – which had degraded under a piecemeal approach to maintenance and repairs – to heritage standards.48 In 2010, however, the housing association informed the tenants of the 99 socially rented households in the tower (approximately half of which had registered their intention to stay) that it was ‘possible but not probable’ they would have a right of return to their homes following the works, citing ‘the impact of the global financial downturn’ and planning setbacks on the estate as the reasons for this uncertainty.49

We began our project with one-to-one interviews with residents using an oral history approach which opens with residents’ first impressions of the tower and moves backwards and forwards from this point – where had they come from, what has happened since – to build a fuller picture of their relationship with the tower and to understand how profoundly these experiences are shaped by personal circumstance. Without fail, and without prompting, every interview referred back to the most famous resident 47 years ago: the architect himself. As our ambitions for the project developed, we became interested in how to re-stage this archival material on site, and brought in two other practitioners to collaborate. Together with oral historian Polly Rodgers and theatremaker Katharine Yates we conceived of a series of performative workshops, running in parallel with oral history interviews, re-enacting Goldfinger’s own empirical methods during his ‘sociological experiment’ to share collective knowledge and experience. These workshops were informed and inspired by architectural historian and designer Jane Rendell’s praxis of site-writing which ‘enacts a new kind of art criticism, one which draws out its spatial qualities, aiming to put the sites of the critic’s engagement with art first’, and forged new connections with critical acts of re-enactment and engagement articulated in the work of performance theorists Rebecca Schneider, Heike Roms and Jen Harvie.50 We set up a poster at community events and bingo afternoons as an invitation for residents to meet their neighbours of 45 years ago.

We held workshops from September 2013 to March 2014, bringing us into conversation with 30 current and former residents of Balfron Tower. In our first, we hosted a champagne (actually discount cava) party in a neighbouring flat to the Goldfingers’ on the top floor. I scripted the dialogue of actors playing Ernő and Ursula Goldfinger based on archival excerpts as well as other brief exchanges between the couple taken from oral history recordings (Figure 8.6).51‘

The Goldfingers’ mingled throughout the evening, asking current residents the same questions about their everyday experience of the tower as they did 47 years ago, this time using audio recorders, not notepads, to record conversations in a dialogue between past and present. I had dressed each room of the two-bed flat with archival material in situ: isometric sketches alongside press cuttings in the study; the many letters that Ernő had written to members of the public in the bedroom; and early photographs of the tower in the living room. The evening concluded with a set of film screenings and talks, including by James Dunnett who spoke about Docomomo, a conservation organisation that campaigns to raise awareness of the ideas and heritage of modern movement buildings, before a short excerpt of a BBC interview with Goldfinger during his stay in the tower.52

Our final workshop was held at the community centre at the foot of the tower in March 2014. We used the occasion to announce that the RIBA had approved our proposal to add our oral history interviews and any further documents residents wish to donate to their Goldfinger collection – updating the records with 47 years’ lived experience. The event re-enacted an occasion when Goldfinger attended an early Tenants Association meeting but, according to the archival record, contributed to the agenda only once, letting the residents share their thoughts openly and without interruption. The actor playing Goldfinger returned to recount his solitary line and it then opened to a group discussion between this community of outgoing residents who shared stories, opinions and feelings – particularly about the renovation and decant of the tower – as they negotiated the array of archives available around the room and on tables. Performing this construction of evidence made the subjectivity and staging of it explicit, allowing the archive, normally seen as having a fixed, authoritative character, to become alive to a more democratic chorus of voices.

Before I reflect on these oral history interviews and group workshops, I draw on residents’ own words from them to identify how this building has framed residents’ daily life and relationships to each other, categorised under six headings:53

FIGURE 8.6,

Actors playing Ernő and Ursula Goldfinger at workshop, Balfron Tower, 2013.

Domestic experience – Common to residents is a feeling of intimidation upon first seeing Balfron, a building many would have never imagined inhabiting. This evokes negative associations, the ‘kind of thing that you think of with inner-city tower blocks, but actually I found it to be a very different experience when I moved in.’ ‘When I knew I had to live here and I didn’t have any choice, I wanted to run away, I didn’t know anything about the tower. As soon as I moved in to the 21st floor I just totally fell in love with it. ’ Instead of the powerful metaphors of war coined by Dunnett, the terms they invoke are more blunted and benign. ‘I know architects think it’s a marvellous thing but it’s just another building to me. ’ ‘It’s a very trendy thing now, it’s in fashion – what I like about it is being inside it. ’

Interior layouts – Residents value the organisation and character of interior layouts, ‘It’s a lovely size in terms of the flat and I love the design’. ‘I think the flats are wonderful places to live.’ ‘I can’t think of anything I’d change in this flat.’ (Figures 8.7 and 8.8) The flats delighted first tenants as they were bigger and lighter than anything they were used to – ‘it was like a palace’ – and are still recognised as superior today: ‘The flats are a great size, spacious – a luxury considering all the shoe boxes being built’, ‘It’s a better design than anything now,’ offering ‘the space to reflect and create’; ‘to live in I don’t think you can get much better’. However, many households on social rent in the tower, particularly Bengali Muslim families, have come to live in overcrowded conditions and would relish the opportunity to move to dwellings with more bedrooms.

Materials and detailing – Over decades of changing fashions, the interiors have been decorated to different tastes – overlaid brick cladding, thick pile carpets, patterned wallpaper – but many of the original design features remain and have lasted well, such as the full-height timber windows, light switches set into door frames and pre-cast flower boxes that have encouraged wildlife – herons, peregrine falcons and ‘squirrels [that] made it regularly to what I assume was the 23rd floor’. ‘The planters are very useful. Since living here my flatmate and I have really got into tomato and marigold growing.’ Residents admire the ‘tremendous force attached to its material and its detailing’ and the privacy that comes from ‘very good soundproofing’ and ‘low noise from neighbouring flats’ which enable some to feel ‘enclosed and safe’. A mother described how it was a nice environment to raise her baby in Balfron ‘because the flats were quiet’ and ‘really well designed’.

FIGURES 8.7 AND 8.8,

Balfron Tower, floor plans and site layout, 1965.

Quality of light and views – Most flats are double aspect except those on the south-face that are triple, and two-person flats featuring a sash window in the kitchen which opens onto the walkway facing east. Though residents complain that the full-height partially glazed screens can be draughty, they cherish the quantity and quality of light they provide. ‘Goldfinger designed with an awful lot of light. You live in the space in a different way. It affects your being. And that’s critical to your entire existence.’

No matter how high residents live, with different proportions of city and sky, the view has become vital to a sense of spaciousness and belonging. It enhances the space in flats, giving the feeling ‘like you have an outdoor space in your front room’, that ‘extend[s] outside the boundaries of our living room’, but also of the estate, ‘The view, not just outwards towards the London skyline but inwards towards the Brownfield area. It’s a very communal view and often there are kids playing in the sunken playground. It’s been lovely these past few weeks of summer to come home and have a cup of tea on the balcony and just listen to the sound of activity below.’ (Figure 8.9)

The view is a source of personal contemplation and identity. ‘The fact that it’s in the sky is so important to it. I do feel a Londoner up here, ironically, you do see the cranes, you see the horizon as it changes, to see the Gherkin being built, to see the Shard, incredible.’ ‘Especially at night ’cos everything was lit up … To me it was just like fairy lights. It was like fairy land, truly.’ One resident who has lived with the view for 20 years fetched a small postcard print of German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog during our interview: ‘That’s me looking out of the window, that’s how I feel looking out of the window. That’s my image of my life in the flat overlooking London.’

The view is also a backdrop and focus to the conduct of communal relationships: ‘You don’t really watch TV when you live somewhere with a nice view... every time you look out you can see different things.’ Residents often contextualised their experience within the prevailing tendency in London to replace post-war social housing with privatised towers: ‘We felt magnificent being up there. The view – we could see Battersea Power Station on a good day – you see everything from there. I think for social housing tenants to lose the view is such a terrible theft of experience.’

Communal experience – The first to move in remember the sociability concomitant with existing communal ties. ‘I was here 40-odd years. I loved it. Everyone would help one another. You knew your next-door neighbour, you knew everyone. Even in the block, because as we moved the whole street moved into the block with us. So we still knew everyone and there was such a friendship and everything.’ When asked about the communal experience today, residents acknowledge the consequences of long periods of poor social policy and unfailingly mention the two lifts that never appear to have been quick or reliable enough. They stand for the lack of sufficient funds for repair and improvement that has afflicted the building in spite of decades of demands from residents, leading to concrete spalling, corroded wiring conduits, leaking pipes and vermin infestations. The eventual installation of a door-entry system at Balfron curtailed instances of anti-social behaviour, but with the hobby rooms sealed off and long forgotten, residents feel the tower is missing spaces to facilitate communal interaction.

Yet the feeling of neighbourliness is not restricted to Balfron’s early golden age. The nine distinct corridors which lead to three levels of flats offer ‘more chance of meeting neighbours’ and can be a ‘great place to meet the neighbours and chat’. The intimacy these spaces provide is unexpected: ‘it is the first time in my life I’ve got to know my neighbours’, the ‘friendliness isn’t something I’ve experienced in other parts of London’. ‘The ethnic community has changed … I am proud that I am a member of a community that includes a staff sister, a child psychologist, a retired woodworker, Somali artists. People from all walks of life and cultural backgrounds. I am proud to be in Balfron Tower, and to be in Tower Hamlets. This is part of my identity.’

FIGURE 8.9,

Residents on balcony during workshop, Balfron Tower, 2013.

FIGURE 8.10,

Residents in kitchen and living room during workshop, Balfron Tower, 2013.

Collective memory – The longest-serving residents remember meeting Goldfinger at his parties. ‘He introduced himself and he asked our opinion of different things, what we thought of this and that. And he weighed it all in, so that when he built the other building, he done the adjustments, you know what I mean … He noticed it all and he righted it.’ Similar anecdotes have survived generations of new residents through continued conversations between neighbours, that have meant residents are well informed and inspired by its history. ‘Trellick is more famous, but this place is more close to his heart in the fact that he lived here.’ ‘I tapped into the Goldfinger thing, I painted my whole flat gold … I felt I could be really creative here ... [it] opened up a new world to me. ’

In each of the oral history interviews we had conducted, residents lamented the lack of opportunities for communal interaction in the tower today. The workshops opened a social, discursive and imaginative space that brought different residents from different tenures together into one space to talk to one another. In this sense, our re-staging touched on the spirit of the original endeavour; a community was not just re-enacted but, if only temporarily, reconstituted. There was a considerable level of engagement with the material on display. Dressing a flat that is identical to residents’ homes as an archive makes it estranging and uncanny, and it forced people to see their own flats differently and acted as a trigger for memories (Figure 8.10). Alongside the informal theatricality, it created a setting where people stepped outside their daily routine into a mode of critical reflection, to re-examine their estate, their flats and themselves.

Residents engaged enthusiastically with the performative premise and spoke freely in their own terms about their homes and the process of regeneration, to each other and to the actors, telling ‘Goldfinger’ of his inspiration to them or telling him off for the things that did not work. As the interviews and encounters progressed, I witnessed how knowledgeable the residents were about the process of refurbishment and the design and quality of their homes but, despite this, they bemoaned the lack of clarity and certainty about the regeneration and their own place within it.

‘On Both Architectural and Social Grounds, a Place Which Needs Preserving’: Activism

The processes of regeneration that had begun during my engagement with residents accelerated in the year leading up to the submission of refurbishment plans in September 2015. Housing association Poplar HARCA entered a joint venture partnership with property developers Londonewcastle and Telford Homes, recruiting architects Studio Egret West and designer Ab Rogers to develop proposals for external and internal physical alterations that would transform the character and tenure of Balfron Tower.54 Below, I summarise our objections to these plans and actions we took beforehand on the grounds of accountable regeneration and informed heritage.

Accountable Regeneration – The application’s 130 documents do not contain a statement on the future tenure of Balfron Tower’s 146 flats, an omission which indicates full privatisation and a resultant loss of 99 homes on social rent. This was in keeping with Poplar HARCA’s policy after October 2010, as they continued to advise tenants that it was ‘possible but not probable’ they would have a right of return to their homes, offering instead assistance to relocate.55 In this time, tenants had sent moving letters of appeal to local newspapers and all levels of representative democracy, drafted online petitions and submitted Freedom of Information requests, but no further information or financial models were released to justify this decision.

It was during our project of interviews and workshops that I had come to realise this proposed privatisation had escaped media, cultural, intellectual and resident scrutiny, in part because of the difficulty of accessing and understanding material related to these complex and contested processes of change. This chimed with the experience of other campaign groups in London where information has been withheld or legislative definitions invoked ambiguously to cover a chasm between the promises and realities of social housing provision.56 As such, six months before the planning application was submitted, I produced an online archive in the hope that access to the full range of information on the history and future of the tower would enable the regeneration process to be subject to critical scrutiny and the force of informed public debate. Although it was late in the regeneration process, if there was still a potential opportunity to intervene and protect the provision of social housing in Balfron Tower as so strongly desired by current tenants and essential to its principles and purpose, then inaction, to me, seemed unethical.

I collaborated with designer Duarte Carrilho da Graça to make www.balfrontower.org, an open-access website as a vehicle to communicate this volume of material which playfully reflects the aesthetic of Balfron Tower – an impossibly tall tower of 120 documents spanning five decades.57 These include adverts, architectural history accounts, archival records, art projects, blog articles, conservation management plans, council minutes, documentary films, feature films, financial viability reports, freedom of information requests, health reports, listing nominations, literary fiction, music videos, planning applications, press articles, promotional videos, public lectures, regeneration strategies and resident oral history testimonies. In their original form, these documents can be intimidating, difficult to access (because they are hidden behind archival protocols, journal subscription costs and labyrinthine planning portals) or difficult to understand because of bureaucratic, academic or legal language. When the user clicks on these documents they are whisked away to other pages, from which unabridged versions of the documents can be downloaded in full or selected key quotes and explanatory comments viewed. The user can also find a list of 13 questions, each of which, when clicked, provides a short answer and selects relevant documents from the timeline below, assembling quotes which act to provide a more detailed response. The website differs substantially from a typical academic output: rather than an authored article that takes time to polish and publish, it presents all relevant documents for the public to easily draw upon, opening up resources for scrutiny and providing the user the ability to construct their own narrative around the evidence in their own terms. The documents included made clear the statutory affordable housing targets and best practice guidelines on accountable regeneration that the planning application failed to meet.

Informed Heritage – on the second point of our objection, the planning application provides a detailed account of the history of the tower, drawing extensively from the excellent Conservation Management Plan produced by Avanti Architects in 2007, which sets out its evidential, historical, architectural and communal heritage value.58 The Design and Access Statement describes Balfron Tower as having been ‘designed with an exceptional attention to detail for a social housing project’ and ‘conceived with a spirit of 1960s optimism, designed to create contemporary housing for the masses and nurture a sense of community’. The importance of the tower’s purpose as social housing for local communities is reinforced by the ‘Hierarchy of significance’. The first point in this section addresses the ‘social and political context’, noting: ‘The need for high quality housing to serve a modern post-war Britain informed Balfron’s design. This is significant in historic and architectural terms.’59 The ‘Summary of significance’ concludes, ‘The iconic nature of the building, being a major selling point, needs to be conserved in its essence, according to the hierarchy of the above attributes.’60

Before I turn to this ‘major selling point’, it is important to address the three ways in which the planning application diverges from Avanti’s recommendations. Aesthetically, the plans set out the removal of the surviving original white-painted timber windows to be replaced with box-section brown anodised aluminium windows alongside stripping out existing flat plans – except for one of each type to be retained – to be replaced by ‘open plan’ layouts. Functionally, they transform these dwellings that were overwhelmingly allocated for social rent into properties for sale on the private market. Finally, in terms of consultation approach, the plans state, ‘As the building is Grade II Listed with design and refurbishment works needing careful consideration to comply with complex planning and heritage requirements, it was not felt appropriate to consult more widely on detailed design and heritage matters’.61 A number of stakeholders were consulted but these included neither current and former residents of the tower nor the wider estate community. To exclude residents who know the building most intimately and assume they could not engage meaningfully in complex discussions is contemptible, especially considering Ernő Goldfinger’s own methods of resident engagement.

This selective reading of Goldfinger’s principles can be further witnessed in the design approach. The development partners state they intend to ‘help realise the vision that Ernő Goldfinger had for it over half a century ago’,62 adding, ‘We want to invoke Goldfinger’s original optimistic spirit and sensitively refurbish Balfron Tower to be a shining exemplar of contemporary living again, this time for the 21st century.’63 The inference from these statements is that refurbishment plans can deliver a vision Goldfinger himself was unable to achieve, reinforced by the intimation that the tower is no longer fit for purpose. They also position Goldfinger’s ‘optimistic spirit’ as a cultural cache which, along with the ‘iconic nature of the building’, is invoked as a ‘major selling point’ to be marketed instead of principles and homes to preserve. The misconception at the heart of these design proposals is a fundamental distinction between heritage that pays tribute to these egalitarian principles and heritage that enacts these principles.

In anticipation of this, I assisted James Dunnett in writing a Grade II* listing upgrade nomination in August 2014, over a year before the planning application was submitted. Our reasons were threefold; firstly, we believed all of Goldfinger’s work on the Brownfield Estate – including specifically the spaces between the buildings which can be vulnerable to development pressures – should be protected to recognise their exceptional architectural quality. Secondly, an enhanced level of listing would ensure Historic England’s active involvement in assessing any application for listed building consent, and thirdly, the current listing descriptions should be elaborated on to reflect the social elements in the design.

On this final point, the principles and grounds of our argument explicitly emphasised the importance of Balfron’s social context, integral to the vision and function of the building and an intrinsic part of its architectural heritage. I had been inspired by campaigners fighting against the conversion of Berthold Lubetkin’s Finsbury Health Centre, and by architectural writer and local councillor Emma Dent Coad, who represents the residents of the Cheltenham Estate comprising Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower. Dent Coad had issued a rallying cry on preserving such buildings: ‘we must get our hands dirty to engage politically, comprehensively and at the right time… If we determine that social purpose must also be conserved, we must look beyond physical conservation and commit to keeping these homes in the social sector.’64 Dunnett produced a rigorous history of the tower, noting: ‘It would be regrettable if the Tower were to be converted into just more housing units on the private open market – as is in prospect: its architectural “message” would be compromised.’65 I accompanied this with a supplementary document devoted to residents’ experiences, challenging the dominant discourse that Balfron Tower has failed, identifying the aspects of the building that residents cherished, and to testify to its ongoing social function.66 And Owen Hatherley wrote a statement in support, concluding:

By the time Tower Hamlets Development Committee met to consider the planning application in December 2015, the archive website had been viewed by residents, community groups and the wider public 12,000 times. Alongside this, I had drafted a fully referenced statement of objection, which was used as the basis of a petition coordinated by tireless resident and campaign groups (Balfron Social Club and Tower Hamlets Renters), amassing the support of 2,800 people in its first week.68 Our objections were further articulated by an Architects’ Journal article by residents;69 enriched by objections on aesthetic grounds by Docomomo-UK and the Twentieth Century Society;70 and amplified by a speech drawing explicitly on our research by Baron Cashman in a debate to the House of Lords on the regeneration of east London.71 This was consolidated by a decision from the other side of the Houses of Parliament. While Balfron Tower Developments had been preparing this planning application, Historic England were completing their year-long assessment of our listing upgrade nomination. One month after the planning application was submitted, the Culture Minister ratified this upgrade to Grade II*.72 The new listing statement recognised the social ideals and purpose of the tower as a key component of its heritage: ‘Balfron Tower was designed as a social entity to re-house a community, according with Goldfinger’s socialist thinking’. And among its ‘principal reasons’ for listing, Historic England noted ‘Architectural interest: a manifestation of the architect’s rigorous approach to design and of his socialist architectural principles’ and ‘Social and historic interest: designed to re-house a local community’.73

I had been driven by the conviction that if all the archival, academic and empirical evidence was presented alongside relevant policy, guidance and precedent, councillors could not help but demand accountability for their socially housed constituents and demand a more informed approach to heritage. Devastatingly, and unanimously, the Development Committee vote to refurbish, and with it any opportunity to prevent the privatisation, passed.74 As we left the council chamber I had in my mind the words of a Municipal Dreams blogpost whose author had foreseen this outcome:

‘An Exemplar’: Concluding Remarks

This sustained engagement with residents reaffirmed the duty we have to put our work at the service of those whose lives we seek to improve. Bringing archival, bureaucratic and academic material into their homes opened access for residents to speak to these debates, and to one another, as peers. Residents’ fuller historical accounts challenge the dominant discourse that Balfron Tower has failed. Their testimonies neither reinforce stereotypical images of high-rise housing estates nor hide their faults; instead they display the liveliness, diversity and vibrancy of such estate communities. In doing so, they advance an argument for the continued and urgent need for public housing as these communities and the qualities they bring to London are diluted or dispersed. By collaborating to produce the online archive, listing nomination and campaign we transformed what had been framed and suppressed for five years as a marginal and private issue into a matter of legislative and public concern which held Balfron Tower as a beacon for public housing, against which current regeneration policy was found wanting.

In the planning application, the development partners define Balfron Tower as ‘an exemplar of post-war social housing’. They introduce their plans to ‘sensitively refurbish [it] to be a shining exemplar of contemporary living again’, and declare their aim to ‘deliver an exemplar project and provide a legacy that all will be proud of’.76 Rather than an exemplar (this word is repeated 18 times in total), the proposals exemplify the current practice of heritage which strips social housing estates of their egalitarian principles and purpose, exemplify contemporary developments that segregate and stratify local communities, and exemplify an unethical dispossession of social housing in London that constitutes a major contributing factor to the city’s housing crisis.

It is perhaps too late for the housing association to reconsider its approach and deliver a truly exemplary project at Balfron Tower, but it is certainly not too late for other developments in London. These could set the benchmark for regeneration and heritage schemes by addressing: accountable regeneration – opening full access to information in order to justify decisions; affordable housing – retaining a proportion of social housing genuinely affordable to local communities; inclusive consultation – developing proposals together with residents in which everyone is able to fully participate; and informed heritage – identifying and preserving shared historical and communal values.