Chapter Five

South Acton Unsustained

PETER GUILLERY

This chapter is a sort of memoir – a reflective and partly rueful account, more than a decade later, of a largely unsuccessful attempt to mobilise housing history. It is about the recidivism of obsolescence, about how serviceable buildings of entirely different types are repeatedly misidentified as the causes of social problems, and about the difficulty of confronting discourses and economic structures that prioritise renewal over continuity. It is also about the importance of retrospection, about how time colours research and knowledge. In 2004–5 I was responsible for an English Heritage survey of South Acton, an area that comprised one of the largest post-war public housing estates in west London, 2,152 homes for about 5,200 people (Figures 5.1–2). There had not previously been any real historical study of the place – the Buildings of England described South Acton as ‘soulless wastes’.1 English Heritage’s own account of London’s suburbs paid regard locally only to the late nineteenth-century development of the Mill Hill Park Estate, seen as compromised by ‘the proximity of the working-class South Acton area with its piggeries and laundries’.2 The South Acton survey came about following an approach from local residents amid intense local debate about regeneration. The South Acton Residents Action Group (SARAG), formed in 1997 as a direct response to regeneration initiatives, found itself alienated from Ealing Borough Council’s plans for partial demolition, new mixed-tenure housing and higher overall densities.3 Fearing the loss of good buildings and open spaces, and the destabilisation of established communities, SARAG initiated its own masterplanning study. Its aims included recognition of the distinct character of various neighbourhoods within South Acton, and concluded by quoting John Ruskin – ‘When we build, let us think that we build for ever.’ SARAG asserted that ‘the history, continuity and community spirit of the area is important and should inform what happens and which buildings are retained’.4

Introduction

The objective for English Heritage (then bearing the responsibilities for the historic environment that have since passed to Historic England) was to take a historical look at the place, to produce what was called ‘historic environment characterisation’. Characterisation was defined by English Heritage as building up ‘area-based pictures of how places in town and country have developed over time. It shows how the past exists within today’s world. These fascinating insights into the historic environment, however, are about the future, not the past. Characterisation is not an academic exercise but a vital tool for developers and planners to make sure that a place’s historical identity contributes properly to everyone’s Quality of Life.’5 In spite of knowledge built up from years of work on the post-war listings programme, English Heritage had no internal models for this kind of assessment in this kind of place. Here was a chance to test the ideals of characterisation against the realities of regeneration and to explore an approach to the historical investigation of post-war housing that would extend beyond hierarchical judgments of architectural quality or significance. It was obvious from the outset that South Acton lacked the distinction that would warrant listing or conservation-area designation. This was not about designation, but about providing a model for the sympathetic assessment of comparable ordinary places. The report did not make specific recommendations. It was, like this book, about what had happened, and only indirectly about what should happen.6

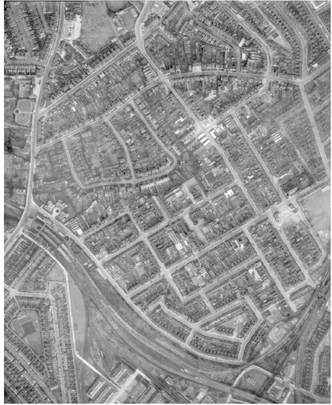

FIGURE 5.1,

Aerial view of South Acton, 1946.

Ealing Council, however, was not just uninterested, but overtly hostile, unable to see beyond the notion that English Heritage equalled preservation, and keen to minimise the complexities of managing an already fraught regeneration programme. Undeterred, we hastened to catch up, taking the buildings as the starting point, and undertaking fieldwork combined with documentary research, photography and phase mapping to construct a historical account. The resulting report, ‘South Acton: Housing Histories’, was basically a chronological story, blending social and economic contexts with details of topographical change and building development, architectural motivation and contexts assessed in passing, and character areas defined in conclusion. There were two appendices, a chronological list of major events and a gazetteer of public housing.7

This was half of a dual approach, the other half being public engagement. A parallel study was commissioned from Fluid, an architectural practice with an admirable track record in community consultation. With the same tight time constraints, Fluid started with a local publicity blitz in schools, churches, clubs and through gatherings at community centres, as well as with a poster campaign. This was accompanied by the distribution of hundreds of cards canvassing responses to seven questions about perceptions of South Acton. A selection of the respondents was then invited to in-depth interviews, of which around 20 took place, lasting around an hour each. This more detailed material was collated and analysed to identify themes that could be said to characterise South Acton. From this, Fluid created an oral history-based synthesis of local residents’ thoughts, memories and feelings about South Acton, presented as another report entitled South Acton Stories: Sharing Histories, Revealing Identity, and as what was called (in retrospect rather quaintly) a ‘digital documentary,’ a CD of short films made up of archive material and interviews with local residents. The two approaches combined in many interesting ways to provide complementary explorations of convergence and divergence between architectural intentions and lived experience, academic and popular histories, official and what Raphael Samuel called ‘unofficial knowledge’.8 Informed by this experience, the abbreviated historical account presented here attempts to integrate official and unofficial knowledge.

FIGURE 5.2,

Aerial view of South Acton, 1971.

What was special about South Acton was, in great measure, its typicality. The place had a subtly unique disposition of familiar and widespread forms, representing virtually all approaches to public housing through the post-war period. Its buildings, most of which dated from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, were high-and low-rise flats, varying in scale, materials and architectural and constructional quality, jumbled together and laid out with lots of open space that had not existed previously. All this arose from a programme of ‘comprehensive redevelopment’ initiated by Acton Borough Council to clear dense late nineteenth-century terraces that had come to be considered slums. Acton and its post-1965 successor, Ealing Borough Council, were entirely responsible for carrying this through. Acton was outside the London County Council (LCC) area, and after 1965 the Greater London Council (GLC) did not get involved. Over the 1980s and 1990s, here as elsewhere, the problems and costs of maintaining public housing mounted, repairs became backlogged, and in 1996 Ealing began to plan ‘comprehensive regeneration’, still utterly typical. In 2001 a 21-storey tower, Barrie House, was demolished for low-rise houses to be built on its site.

South Acton could be looked at as a kind of architectural zoo, an exhibition of housing types, dissonant in its combinations, and instructively representative of changing approaches through a long period. Post-war housing is seldom treated by architectural historians other than like this: in isolation, as a subject in its own right. It is rarely connected to nearby earlier and later developments, private, public or social.9 Linking housing across historical periods, and across building types in a specific broader local context, helped make sense of the place, characterising mix rather than highlights, and revealing that South Acton was not, in fact, an exhibition, but rather a vernacular settlement. Finally, the extents to which reception, use and adaptation as opposed to design have affected (or failed to affect) what was initially provided were taken into account. Alterations can obviously be as revealing as original form.10

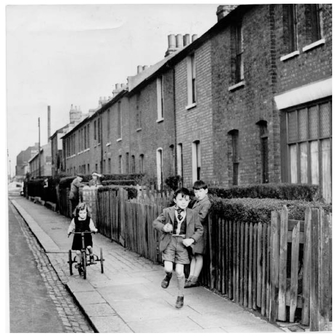

FIGURE 5.3,

Osborne Road, houses of the 1860s in 1954.

South Acton is a suburb, and suburbs are maddeningly mutable things, geographically, architecturally and temporally. Contingency is in their nature, and multiple identities and boundaries are not only possible, but inevitable. The placing of a peripheral place like South Acton at the centre of attention is itself a play with identity, a trick of the map. So we treated the area’s boundaries as soft, to reflect changing perceptions as to what actually constitutes South Acton. For example, an area between Acton High Street and Avenue Road was not considered a part of South Acton until it was redeveloped for public housing in the 1970s – thereafter it was lumped together with the rest of the estate. On the other hand, the area southeast of the railway was thought to be South Acton before the Second World War. However, it was not comprehensively redeveloped thereafter and had come to be known as Acton Green – lacking Modernist housing and having been gentrified, it seems it could no longer be South Acton.

A major finding – though not a surprise – was how important, and how utterly forgotten, Victorian development, industry and demography had been in determining the separation, or, in professional jargon, impermeability, of the neighbourhood in the first place. South Acton’s ghettoisation had been assumed to be nothing but a product of post-war redevelopment. In fact, it has much deeper roots, even though boundaries have shifted.

South Acton's Housing Histories

The story starts, as usual, with the arrival of the railways. After the Enclosure Act of 1859, an 85-acre estate was acquired by the British Land Company. This enterprise was an offshoot of the National Freehold Land Society, which had been formed by Liberals in the 1840s to buy land to sell to humbler party members, in plots just large enough to make them eligible to vote, incidentally facilitating the building of homes for artisans. New roads (Mill Hill Road and Avenue Road) were formed, and a number of villas were built in the early 1860s. Middle-class housing proved difficult to let, and subsequent development into the 1870s was on a smaller scale. The area south of Avenue Road was laid out on a grid as a firmly working-class district (Figures 5.1, and 5.3). Local employment (principally in laundries) and housing, as well as shops and pubs, were all intimately and densely integrated. Unlike neighbouring areas, South Acton was not a commuter suburb; its comparatively poor transport links made it self-contained and self-sufficient. By the 1890s the area had more than 200 laundries, small domestic concerns. It came to be called ‘Soapsud Island’. From about 1880 many houses were built with integral workshops, cart entrances leading to yards and long rear ranges with wash-houses below mangling and ironing rooms (Figure 5.4). There was also a good deal of pig-keeping.

FIGURE 5.4,

59–63 Osborne Road in 1964, shortly before demolition.

Meanwhile, just to the north-west, William Willett began in 1877 to develop the Mill Hill Estate as a select suburb, emulating Bedford Park. This was deliberately sealed off from the rest of South Acton, brick walls creating an impermeable enclave. Willett could not override South Acton’s entrenched working-class character, however, and the estate was not a big success, stagnating in the mid-1880s. Houses were subdivided and in many cases became overcrowded. Other late nineteenth-century and Edwardian development, further east, was largely in the form of cottage flats, two-storey terrace ‘houses’ designed as flats (see pp41–42).11

In the early twentieth century, ambitious developments in London’s western suburbs signalled idealistic, even utopian, approaches to the improvement of working-class housing. A famously progressive local model was the Brentham Garden Estate in north Ealing, a project begun in 1901 by a co-operative society, Ealing Tenants, as self-help housing for working people, and boosted from 1907 by the involvement of Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker.12 A new role for local government was also soon locally evident. From 1911 the LCC built the Old Oak Estate in East Acton, which was among the best of the picturesque cottage estates that grew out of Arts and Crafts and garden-city ideals to become admired throughout Europe. After the First World War and the homes ‘fit for heroes’ Addison Act of 1919, the Wormholt Estate followed. But in South Acton proper, council housing did not appear until the early 1930s, and then only in small blocks. Alongside co-operatives and council housing there were also ‘public utility societies’ (what would now be called housing associations). The United Women’s Homes Association provided housing for single professional women near London’s stations, as on the west side of Gunnersbury Lane in the late 1920s and early 1930s; across the road, Gunnersbury Court, a private development designed by cinema architect J Stanley Beard, followed on from the rebuilding of Acton Town Station for the Piccadilly Line in 1936. Flat living was fashionable.

South Acton, however, had declined. Its late nineteenth-century building stock, then about 50 years old, suffered from poor maintenance and, with sub-division of houses to flats, population densities increased to around 70 people per acre (ppa) in 1919, compared with only about 15ppa in adjacent wards to the north. In assessing this density it must be recalled that South Acton also contained all its laundries and other industry (Figure 5.4), and that ‘the streets were wide, there were no back-to-back houses or courts, and every dwelling had its own garden and yard’.13 There were spaces between the houses, but South Acton was no garden suburb (Figure 5.1). Of private garden space in the 1930s, Reg Dunkling recalled that ‘some enthusiasts cultivated a few flowers and vegetables but most just used it to store their unwanted junk … The poet who wrote about England’s “green and pleasant land” never lived in South Acton between the wars. Except for one small recreation area besides All Saints Church the green fields of yesteryear were covered by houses and laundries, and “pleasant” would in no way be the word to describe the life of the inhabitants. In the winter time, the smoke from industry and domestic chimneys added to the general gloom that existed in the area and even in the bright days of summer the grimy, featureless streets had little to commend them.’14

Bomb damage in the Second World War exacerbated housing shortages, while also creating open space. Densities rose to about 100ppa around 1950 and in 1956 Acton still claimed to be ‘the largest laundry town in Britain’.15 The post-war consensus, here as elsewhere, was that the slums needed to be swept away to improve the lives of their poor and exploited residents. The Greater London Plan of 1944, devised under the leadership of Sir Patrick Abercrombie, proposed population dispersal and declining densities from centre to edge, from 200ppa at the centre to 50 at the periphery. It suggested 136ppa for inner suburban districts, which included much of the LCC area. In these terms South Acton presented an interesting case, outside the County of London, but entirely urban, and thus essentially ‘inner suburban’. In a ‘flats versus houses’ debate it was clear that the former were inescapable for such densities, though prospective tenants generally always preferred the latter. Flats were also thought necessary to admit light and air, and to get away from the ‘confined’ limitations of streets. The new climate of centralised state planning represented a marked contrast to the uncontrolled speculative building and private landownership that had failed to sustain amenity in South Acton. But there was not yet a fundamental shift to planned as opposed to opportunistic development. Abercrombie knew that flexibility and pragmatism was necessary, noting too that ‘it is in relation to density that so many planning schemes tell the gaudiest lies’.16

Renewal was not easily or rapidly achieved. The Council acquired land in South Acton in 250 separate and largely compulsory purchases between 1908 and 1975. Early infill blocks included Bollo Court (1949–50), 32 maisonettes on the south side of Bollo Bridge Road that were among the earliest council homes to have central heating. Another, further north, was St Margaret’s Lodge. There, it was said, ‘children threw rubbish through the lower windows and generally made themselves a nuisance’.17 Acton Council urged more intensive policing while for some there was a belief that rebuilding would bring social reform. A Bollo Court resident wrote, ‘Never has a re-housing plan been so desperately needed from the moral welfare point of view of the young teenagers of South Acton. Never have I seen so many youngsters with so much time to create so much noise, managing to break so many gas lamps and milk bottles and generally make such a nuisance of themselves.’18

FIGURE 5.5,

Woolf Court, 1952–4, and Maugham Court, 1961–2, in 2004.

FIGURE 5.6,

Hanbury Estate, 1955–9, in 2004.

As this suggests, plans for ‘comprehensive redevelopment’ had been promulgated. These marked the beginning of a 30-year programme that was repeatedly adjusted to take account of changes in central government policy along the way. In 1947, striking a cautionary note against the notion of rebuilding as reform, the parish vicar Reverend Harry Nicholson commented:

This was later reinforced from the same pulpit by the Bishop of London, Dr JWC Wand, who warned that ‘it did not matter how splendid the buildings were after redevelopment[;] if there was no centre around which the people could gather there would be no community spirit’.20 Buildings at the estate’s south end, which had been the area’s roughest district, marked South Acton’s first shift towards height and Modernism, initially in a somewhat Danish stock-brick manner, then taking more of a cue from Powell and Moya’s Churchill Gardens in Westminster (Figure 5.5). Design was overseen by Stanley Slight, Acton’s Borough Engineer.

The project’s third stage in the late 1950s, still under Slight, was the Hanbury Estate (Figure 5.6). High- and low-rise blocks were arrayed in what had become an orthodox manner. Post-war deliberations on the relative needs for houses, flats and maisonettes resolved around 1950 into a progressive consensus for ‘mixed development’, which referred to variety in visual and architectural effect as well as to building or dwelling size, but crucially also carried implications of a diluted social-condenser ideal that Nye Bevan articulated in 1948: ‘We have to have communities where all the various income groups of the population are mixed.’ For the integration of blocks of flats with new social amenities, the LCC’s late 1940s development of Woodberry Down was a model. There working-class housing in Zeilenbau (parallel slab blocks) was introduced into a middleclass district to create mixed tenure. Government stopped using the term ‘working-class housing’ in 1949.21

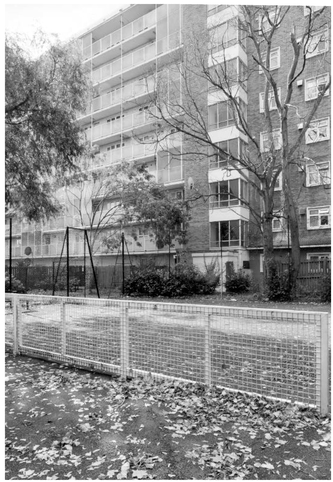

FIGURE 5.7,

Tennis court adjoining Grahame Tower, Hanbury Estate, in 2004.

South Acton had none of the social engineering tensions of Woodberry Down, and Acton Council was deliberately not aiming at the 1944 plan’s ‘inner suburban’ (136ppa) measure. Density was held stable at around 100ppa for the sake of generous open space. The objective was the rebuilding of an already working-class area for a working-class population, yet the principles of ‘mixed development’ – dominated by tall blocks and landscaped open space which had come to be seen as ideal for ‘inner suburban’ areas – were applied. However, where houses and blocks of flats came together, few people ever wanted flats, houses always being much preferred – a preference that density requirements and subsidy regimes overrode.

Novel features on the Hanbury Estate included frosted and toughened glass on balconies, as used by Powell and Moya, and an amplifier ‘to eliminate the unsightly appearance of individual television and wireless aerials’.22 An elaborately planted central courtyard had a playground with a concrete ship, and there was a tennis court (Figure 5.7). The spacious ‘multi-coloured “skyscraper” flats’ were well received when new: the kitchens were thought ‘a housewife’s delight’ and ‘Bathrooms for several of the families were something they read about in glossy magazines: separate bedrooms for children and parents unknown; and as for central heating, well, it was a dream.’23 As Alfred Harms witnessed, ‘Our rent has nearly doubled now, but we are glad to move.’24 A three-bedroom flat in one of the towers had 871 sq ft (78 sq m), more space than many of the area’s nineteenth-century houses, many of which had anyway been divided, and more than the area’s three-bedroom flats of the early 1930s which had been laid out according to the Tudor Walters report space standards.25 There were also refrigerators and ‘caged’ flat roofs for clothes drying on the taller blocks (though not on the lower blocks, to avoid unsightliness). The drying of clothes on balconies was strictly forbidden; ‘if you dare hang one item on your balcony, she [council official]’d be up like a shot, and if you argued with her and said you weren’t going to take it down you’d be threatened with eviction.’26

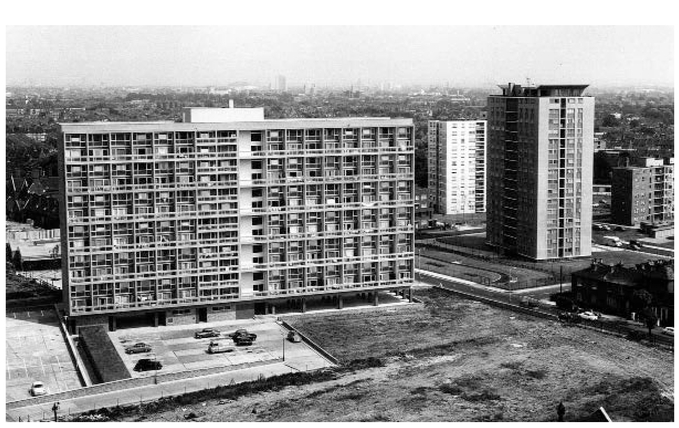

FIGURE 5.8,

Charles Hocking House (1965–7), with Blackmore and Kipling towers (1963–5) to the south, in 1967; demolished c.2012.

From 1955 onwards there were objections from the Mill Hill Park Estate to what was happening South Acton, especially as regards the height of new blocks. When plans were made public for Doyle House, just south of Mill Hill Park, it was asked, ‘are we going to have a laundry on the top with washing flapping about on Sundays?’27 It was conceded that private gardens should not be overlooked. Immigration, too, began to become an issue. In 1956 an anonymous tenant urged action ‘before the flats are flooded with coloured people’.28 The South Acton Tenants Association was formed in 1960 because, as was said, ‘The people round here just do not know what is happening’.29

True tower blocks followed, largely as a result of central government subsidy rules and density obligations. The first, Jerome Tower (1962–3), of 16 storeys, was built with pride. On a spring Saturday in 1964, Acton Council issued tickets to the general public for access to its newly completed roof terrace – with an aerofoil, just for stylish fun.30 After local government reorganisation, several more towers and slabs were seen through on the estate’s east side (Figure 5.8). Thomas Norman I’Anson, Ealing Council’s first Borough Architect, was influenced here by the LCC’s slab blocks at Alton West, Roehampton. There was no landscaping to match that, but there was a deliberate and typical eradication of the old street pattern to separate vehicles and pedestrians for the sake of safety and amenity (Figures 5.1 and 5.2).31 A new shopping parade, Hardy Court, was welcomed in 1965 by resident Doris Swinfield, as ‘one of the finest things that have ever happened down here in South Acton. The shops are clean and the service is much quicker now. I can remember queueing up for an hour in the old grocer’s shop, but shopping takes no time at all in the supermarket. I have lived here for 15 years and it is only now with the new shops and flats being built that the terrible stigma that has been over South Acton for years is being lifted. The area is becoming so much cleaner and more respectable.’32

With the Council under great political and demographic pressure to get more housing built, the mixed-development approach had broken down in the pursuit of volume. There were no more enclosed courts, rather a shift towards parallel ranks – the Zeilenbau approach. Densities were increasing, by virtue of the sheer size of the buildings, but the spaces between the blocks had also increased (otherwise the attempt to increase light would have been defeated). Open space was anyway still regarded as a virtue in and of itself.33 These changes, as much as changes in the elevational design and materials of the buildings, undermined whatever residual coherence there might have been in the continuing staged comprehensive redevelopment.

As generous as the architecture was in terms of space, indoors and outdoors, upkeep was immediately a problem. Windows were leaky and uncleaned; the Council suggested tenants should clean them from the inside. ‘The Green has been left in a mess for six years’, one resident complained in 1963. ‘It is miserable to look out on.’34 There were also persistent grumbles about anti-social behaviour, litter, urination in lifts, and dogs fouling playgrounds. ‘Instead of living in pleasant and pretty surroundings the estate is being turned into slumland, caused by the “little darlings” [who] pull up the flowers by the roots … after the hard work and money spent by the Town Council.’35 In 1966, nearly 600 Hanbury Estate residents signed a petition protesting about lack of maintenance, especially to the lifts.36 One resident who was then a child has since reminisced, ‘It was a great place for children, but … it was one of the most dangerous places anybody could ever mess around in. It was like playing in a minefield. Whole streets derelict. All windows smashed, because it was us, the kids, who smashed them. Any plain glass that’s whole you pick up a stone and smash it, you see. We used to run in and out of the houses. We used to play run outs. No-one wants to be caught so you find any means of escape, so we were running around on the roofs.’37

Towers continued to be built, with three to the north that came to be known as the Castles (Corfe, Harlech and Beaumaris) completed in 1971. Cost-cutting from 1964 onwards, especially after the introduction of central government controls (yardsticks) in 1967, accelerated a decline in the quality of the housing. Minima became maxima.38 Densities in South Acton’s post-yardstick blocks rose to 138ppa, above the 1944 plan’s ‘inner suburban’ measure. By this time, and before the Ronan Point disaster of 1968, a reaction against towers had set in. First plans for the area north of Avenue Road, hitherto not regarded as part of South Acton, envisaged more high-rise in 1967. The scheme was repeatedly revised up to 1971, first to omit towers, but then gradually reinstating them to achieve necessary densities. What came to be called the ‘red brick’ was built with facings in that material in 1974–81 as a mostly low-rise post-Lillington Gardens warren. It was largely welcomed, some new residents still having previously lacked indoor baths and toilets.39 The estate as a whole had already been stigmatised. In 1973 Sir George Young, a Conservative representative for Ealing on the GLC who became MP for Acton from 1974 to 1997, sponsored a survey of tenants. Fewer than 20% responded, but, of those, 90% thought tower blocks were a mistake. The Acton Gazette splashed the headline ‘The Awful Truth About Life in Acton’s Tower Blocks – It’s sheer misery, say tenants in shock survey’.40 The newspaper followed up a year later with, ‘It’s hell – they want to get out: Caretakers’ wives tell of threats, filth and terrorism.’ Iris Fogelberg, wife of the caretaker of Barwick House, said:

Even in this tower-phobic context, ‘other people’ are represented as a bigger grievance than building heights, suggesting there was already the problem of what has been called ‘residualisation’.42

The implicit contract with the future that the great post-war building programme had made was that the results of its housing crusade, its investment, would be appreciated and nurtured. But social and housing policies changed and this did not happen. Finding money for expenditure on maintenance and management was increasingly difficult. It was a cruel irony for much of the nation’s council housing that heavy maintenance costs began to kick in heavily in the 1970s just as there was a shift away from large-scale public investment. Attempts at improvement followed, but these were doomed by a fundamental lack of investment in maintenance and repair through the 1980s and 1990s. South Acton was addressed in a report of 1977 commissioned by Young from Simon Morris, a student member of the Tory Reform Group. The report chronicled the extent of crime, vandalism, poor maintenance, anti-social noise and racial problems, though overlooked contrary evidence such as tenant rotas to clean common areas, allegedly without interviewing either those then defined as ‘black’ tenants or council officers. Having recommended reduced densities, it concluded:

This reflects the influence of Oscar Newman’s Defensible Space: People and Design in the Violent City (1972), which blamed architectural design for increases in criminal activity. But again it is social fluidity (residualisation), not the buildings, that is said to be the ‘root cause’ of ‘troubles.’ Sadly less influential than Newman, though more insightful, was the observation in 1974 from Colin Ward, then education officer at the Town and Country Planning Association, that ‘It won’t work without dweller control … The only solution I can see to the malaise of the municipal estate is to transform it into a co-operative housing society.’44 In 1979, insensitively following Newman’s suggested strategies rather than Ward’s, Ealing Council brought in the National Association for the Care and Rehabilitation of Offenders to advise on defensible space. Security was repeatedly thereafter readdressed (Figure 5.9).

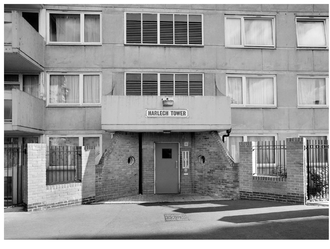

FIGURE 5.9,

Harlech Tower entrance, built 1968–71, enclosed 1980–2, and further altered in 1989–90 and 2002–3.

In considering adaptations and alterations to buildings it should first be acknowledged that an absence of alterations tends to reflect a kind of sustainability, or at least inhabitability. On the other hand, interventions, sometimes serial, do not necessarily reflect more than perceived failure or uninhabitability. Negative perceptions have in themselves undermined sustainability, most notably in tower blocks. Inadequate maintenance and management created an impression of inflexibility, and a vicious circle in which piecemeal and half-hearted alterations chased solutions to problems that need not have been allowed to get out of hand. In 1999 Clive Soley, Acton’s Labour MP, said, ‘There were too many false starts in the past and not surprisingly, residents became cynical.’45

Crime remained an external preoccupation. Yet over time, and for many in late twentieth-century South Acton, social and racial mix became itself a source of security and safety. ‘I’ve never felt threatened … if you’re living in it you don’t see it that way. You see it as your neighbours, friends … you don’t see it as a place of danger. [South Acton is] perceived in a horrible way by other people who don’t live here.’46 There had been ‘phases of different countries coming in. Every time a new country starts sending their people in the animosity changes to the next race.’47

Starting in the 1960s, a new kind of separation had developed – one in which immigration was only an incidental scapegoat. Redevelopment had hastened the end of the area’s self-sufficiency; industry and jobs had moved away. The old houses had themselves been stigmatised, but in some respects the new housing intensified the area’s impoverishment. Poorer and often unemployed people arrived, and shops and pubs declined, for local and wider reasons. The strangulation of streets, intended to make the area safer, ensured a degree of quiet, but quickly became unpopular and reinforced the already existing impermeability. Despite the enduring consciousness of South Acton as a distinct place, people sometimes perceived their own neighbourhood within the estate positively, while viewing other neighbouring localities negatively.48 The deliberate intricacies of the 1970s ‘red brick’ came to be especially disdained – ‘it is an almost impenetrable maze to those unfamiliar with it’.49

South Acton had unintentionally been transformed from a place characterised by diversity of use in a relatively uniform built environment to one with a diverse built environment sustaining uniformity of use. The clear differences between housing types and the absence of overall architectural integration arose not by design, but from the protracted and stuttering realisation of post-war plans. The extension across 30 years of what had been intended as a ten year ‘comprehensive redevelopment’ programme – for reasons that are not at all peculiar to South Acton – increased the impact of changes in central regulation and architectural design.

The post-war redevelopment of South Acton had taken 30 years to see through. Less than 20 years later, another comprehensive fresh start was seen as necessary. In 1996 plans for what was called ‘comprehensive regeneration’ were brought forward. The first fruit was a neo-vernacular row of four-bedroom houses on Bollo Bridge Road, built for the Ealing Family Housing Association (later part of the Catalyst Housing Group) with SARAG, and John Thompson and Partners as architects. In 2002–4, the same parties minus SARAG replaced 21-storey Barrie House with more low-rise housing. Meanwhile Ealing Council began work on an Urban Design Framework and appointed masterplan architects, ECD Architects and Proctor and Matthews. The result was an outline plan for a five-phase ‘fundamental overhaul’ of the estate to make it a new ‘high-density urban quarter’. It envisaged selective demolition, new mixed-tenure housing and higher overall densities. Ealing Homes (an Arm’s Length Management Organisation) was formed to manage all Ealing Council’s housing from 2004.

There things stood at the time of the English Heritage and Fluid reports of 2005. If any lessons were drawn from that work by those responsible for the forward movement of ‘comprehensive regeneration’, they did not lead to a more conservative approach. In 2009 Ealing initiated a new round of masterplanning through HTA Design; as the Council’s website relates, ‘Acton Gardens (a collaboration between L&Q, one of the largest housing associations in the UK, and house-builder Countryside Properties) won a competitive competition to become the council’s developer partner in 2010, and a widely-consulted “master plan” to guide future development was given the go-ahead in 2012 after one of the most comprehensive consultation programmes of its type.’ Complete replacement of the post-war housing had emerged as the preferred approach and the redevelopment programme was extended – the new ten-phase masterplan for around 2,500 homes designed by a number of eminent architects now anticipates completion in 2026. Once again, what had begun as a ten-year project had been recalibrated to take 30 years. Redevelopment south of Bollo Bridge Road was seen through by Catalyst (Communities Housing Association) to form the Liberty Quarter; the freeholds of the sites yet to be redeveloped were to transfer to the London & Quadrant Housing Trust in phases, and South Acton thus moved on to a multiple landlord future. HTA’s mixed-tenure redevelopment of the Hanbury Estate, ‘Phase 5’ of Acton Gardens, began in 2015 (Figure 5.10).

Overall, half of the new housing is forecast to be ‘affordable’, the other half not – though for many South Acton residents, as across London, what is deemed ‘affordable’ is in fact not. While this ratio of ‘affordability’ is good by the standards of early twenty-first-century London, it means that if the redevelopment is seen through, South Acton will have around 900 fewer affordable dwellings than it did in its council housing, for an overall gain of only about 350 homes.

A large mural, Big Mother by Stik, depicting a mother and child 125 ft tall, arrived in 2014 to grace the end wall of Charles Hocking House, scheduled to be demolished in 2017, and to comment on housing provision. The artist has said: ‘Affordable housing in Britain is under threat, this piece is to remind the world that all people need homes,’ and ‘I won’t get any more commissions from Ealing Council, that’s for sure.’50

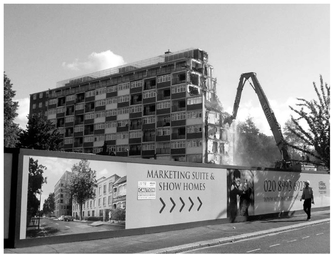

FIGURE 5.10,

Hanbury Estate demolition, 2015.

Conclusion

South Acton’s first development was a product of Victorian Liberal and democratising capitalism. A strong social fabric resulted, but private ownership allowed built fabric to decay. Post-war socialism replaced the built fabric to uphold the social fabric, but in the absence of follow-through both suffered, though not without resilience. Neoliberalism is now replacing the built fabric and transforming the social fabric. The latest masterplan aspires to the creation of a sense of place, to open spaces and to distinct character areas – all of which already existed.

South Acton has been in almost constant flux, and will have been, ‘comprehensively’ so, for 60 of the 80 years up to 2026. Yet it had until recently also kept a continually distinctive and separate identity. Much of the area’s historical character and many of its perceived strengths derived from its relative isolation and long-standing impermeability. The notion of community, always questionable, can be rooted in class or ethnicity; underneath, however, it frequently and obviously has a topographical sense. If strongly felt this can override other more divisive and identity-based senses, and cope with social fluidity. That happened in South Acton, in part precisely because of outside stigmatisation. If a place is opened up, its separate history eradicated, perceptions of community will abandon topography and retreat to other identities, not least class. Oppositional conservationism in this context is not about the preservation of artefacts, but the mediation of change in everyday social environments for continuity and solidarity.

That, at least, had been our hope, and our work was for the most part well received. Local exhibitions, walkabouts and lectures elicited comments like, ‘Learning a bit about the history of the blocks themselves, you do start looking for certain things, you just start thinking.’51 But it would be naive to claim that our characterisation met the high ideals posted on the English Heritage website. With breathtaking cynicism, a councillor welcomed the study as affirming that the Council was heading in the right direction because English Heritage made no recommendations for listing – hoist with our own corporate petard.

Disjunctions of architectural scale, materials and forms can be enjoyed for their drama, or decried for their dissonance. But the substantial difference in scale between pre- and post-war buildings is not fundamentally a matter of taste or style; it was the result of a consistent commitment through the comprehensive redevelopment period to the introduction to the area of open space without a reduction in population density. This was only slowly and painfully achieved – a point that it seemed vital should be appreciated in 2005 if the even greater difficulties inherent in intended increases in density alongside the maintenance of green space and a reduction of architectural scale were to be confronted. Questions about density and mixed tenure that were being posed then were remarkably similar to those posed half a century earlier, but lacked awareness of the precedent. These questions still hang heavy and there are already complaints about reductions in indoor space and light, as well as of poor maintenance, from those recently rehoused south of Bollo Bridge Road.52

A long historical view of South Acton shows the present ‘regeneration’ to be just the latest phase in an almost continuous sequence of restless and deliberate subversions of sustainability, similar in their desire for new building, but reconditioned by ideological shifts within capitalist frameworks. Whatever the complications of tax regimes, energy efficiency, mixed tenure, densification, space standards, or affordability, if sustainability means anything it must mean making what exists work, whatever its flaws – in other words, maintenance. In attempts at renewal mistakes are inevitable, now as much as then; technological, environmental, social and political change in the next 30 years will render what is being built now obsolescent, or seemingly so, until and unless there is a basic acceptance that to keep replacing buildings and displacing people is itself unsustainable. ‘Capital loathes the old, for anchoring us in the reality of the lived’53 – or, to quote Ruskin again, ‘I cannot but think it an evil sign of a people when their houses are built to last for one generation only.’54

Since our survey, redevelopment has proceeded with scant regard to history: neither to the built environment it supplies, nor to the lessons it teaches. Yet more than 40 years after Colin Ward first saw the need, SARAG moved on to spark the transfer of control of aspects of a shrinking estate (including the public realm) to the tenants themselves, establishing South Acton Community Builders Co-operative Ltd, a Tenants’ Management Organisation (and one of ten national Guide TMOs). Historical awareness played a role in building impetus for that, and has been a seed in discussions with tenants of estates elsewhere. More than ten years on, our survey is seen and used as a point of educational reference, as in an annual ‘Ruskinian Walk through Shared Heritage’. SCBC could yet play a role in holding South Acton together. In the face of such great forces, that is how and where housing history can be mobilised: to bear witness and to shift incrementally the way places are perceived, working towards a future in which architectural imagination can align positively with social justice and self-determination.