Introduction

George Kline was a venture capitalist. For those who knew him in the business world, he seemed to be a person of high integrity and truly “Minnesota nice.” But in 2003, George was sentenced to six and a half years in federal prison and fined $5.25 million for insider trading. His two sons were also convicted of felonies. News reports at the time recounted how trading stock tips over coffee breaks at the IDS Center in downtown Minneapolis had mushroomed into a massive deception that engulfed George, his sons, and several business associates.

Contrast this to Craig Ueland's story. Craig is the CEO of the Russell Investment Group in Tacoma, Washington, a highly respected and admired international financial services company with over $125B in assets under management. It is owned by Northwestern Mutual in Milwaukee. Craig told us that when he was in college, it occurred to him that it would be useful for him to decide what principles and values he would honor as he entered his business career. He was an undergraduate at Stanford at the time and said he can still recall where he was walking on campus when he had this insight. Craig explained, “I decided that I would live by three principles. First, when faced with a major decision, I would try to do what was best for society, next what was best for the business and finally, I would consider my own needs. Secondly, I decided that until I was 30 (later he changed this to age 35), when faced with a career decision, I would choose the opportunity that allowed me to learn the most and secondarily would consider the money involved.” Then Craig told us his third principle. “I vowed that I would take all my vacations!” This formula has obviously worked very well for Craig. He's at the peak of his career, is happily married, and is a very engaged father for his two small children.

When George and Craig were both young college students, we imagine it would have been difficult to see any major differences between them—both from good homes, both very ambitious, and both excited about moving into a business career. But Craig deliberately charted his life course in a way that George apparently neglected. One is now the CEO of a major global business and the other is participating in a government-sponsored residential program—a federal prison camp!

In the mid-1990s, well before the scandals of Enron and WorldCom and before the dot.com bubble burst, we had a conversation both authors vividly recall. Doug was then executive vice president, Advice and Retail Distribution for American Express Financial Advisors. Doug was well-known for developing a high performing sales force of approximately 10,000 financial advisors and was an early champion of emotional intelligence skills training at American Express. Fred, a pioneer in the field of executive coaching, was a psychologist and co-founder of a leading executive development company and then as now, actively engaged in helping senior executives improve their personal performance as leaders.

As we talked, we realized that we had some common ideas about the ingredients of high performance that we were both struggling to conceptualize. We agreed on the importance of emotional intelligence—the constellation of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management skills that are now commonly regarded as critical to success in the workplace.1 We discovered, though, that neither of us thought emotional intelligence was sufficient to assure consistent, long-term performance.

In the course of nearly 30 years, we had collectively worked as business executives, entrepreneurs, and leadership consultants to chief executives and senior leaders of Fortune 500 companies, large privately held companies, and start-ups. We had each coached hundreds of leaders. The most successful of them all seemed to have something in common that went beyond insight, discipline, or interpersonal skill. We also spoke about noted public figures with masterful emotional intelligence skills who would sway like reeds in the wind when faced with morally loaded decisions. We hypothesized that there was something more basic than emotional intelligence skills—a kind of moral compass—that seemed to us to be at the heart of long-lasting business success. We decided to label this “something more” moral intelligence.

Moral intelligence is “the mental capacity to determine how universal human principles should be applied to our values, goals, and actions.” In the simplest terms, moral intelligence is the ability to differentiate right from wrong as defined by universal principles. Universal principles are those beliefs about human conduct that are common to all cultures around the world. Thus, we believe they apply to all people, regardless of gender, ethnicity, religious belief, or location on the globe.

Our shared notion that moral intelligence was key to effective leadership led us to wonder: How do leaders get to be moral—or not? Are people born that way? Does our human “hardwiring” predispose us to be concerned for others? What accounts for the wide differences in moral behavior among leaders? Have we learned anything new about human nature over the past few decades that could help us understand the impact of moral sensibilities on leadership behavior? What do the fields of philosophy, social biology, developmental psychology, cultural anthropology, and the neurosciences have to say about these questions?

Before progressing to further develop our hypothesis, we hired crackerjack researcher, Orlo Otteson, to help us review the academic literature on the moral dimensions of human nature and experience. Orlo first reviewed over 1,800 article abstracts referencing moral leadership from the fields of business, religion, philosophy, anthropology, sociology, and political science but found few in-depth moral leadership discussions. Most articles focused on a specific kind of leadership (business, political, religious), on a specific leadership problem, or on the general need for honest and upright leadership. He then surveyed nearly 400 books and articles on morality from the disciplines of philosophy, psychology, biology, and neuroscience, distilling their insights as they applied to leadership and organizations.

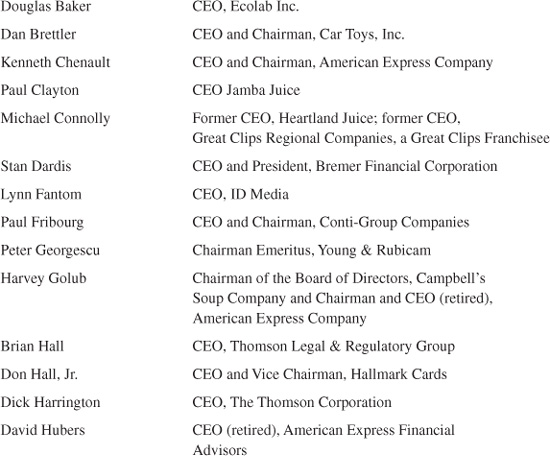

Meanwhile, we began to organize our observations of the many hundreds of leaders we had encountered in our work. As our conviction about the importance of moral intelligence grew, we conducted in-depth interviews with 31 CEOs and 47 other senior executives to learn the precise ways that they deployed their moral intelligence to achieve important personal and business goals. We also discussed our ideas with many talented leaders and colleagues whose penetrating feedback helped us deepen and refine our approach to moral leadership.2

Scientific research supported our initial notions about the importance of moral intelligence for individuals, organizations, and societies. But it was our interviews and observations of leaders that taught us exactly how the best of them used their moral intelligence to overcome obstacles, consistently outperform their rivals, and quickly pick up the pieces when they occasionally missed the mark.

Having analyzed their experiences, we concluded that strong moral skills are not only an essential element of successful leadership, but are also a business advantage. Indeed, the most successful leaders in any company are likely to be trustworthy individuals who have a strong set of moral beliefs and the ability to put them into action. Furthermore, even in a world that occasionally rewards bad behavior, the fastest way to build a successful business is to hire those people with the highest moral and ethical skills you can find.

Business leaders have gotten a bad rap in the first years of this decade. Yes, of course, there are the “bad eggs,” and they get a lot of press. But most business leaders are not like those in the newspapers. Consider, for example, a story we heard from Peter Georgescu, chairman emeritus of Young & Rubicam, who built a large advertising and marketing company and is widely known as an inspiring leader.

“Back in the 1980s, Warner Lambert approached us because they wanted to diversify their consumer products by selling sunglasses. They already had a celebrity spokesperson lined up, and they wanted us to advise them on how to roll out the new product. They told us we were competing with five other agencies to produce the best campaign. After we did the research, our group concluded that Warner Lambert wasn't going to be able to get enough market share to make the new product line successful. We had significant debate about whether to present a campaign anyway, but finally our group went to Warner Lambert and said, “We know this isn't what you want to hear, but we think the sunglasses line is a bad idea.” We explained our reasoning. They looked a little surprised, said, “Thank you,” and that was the end of the meeting—we had no idea what they thought.

Then a few weeks later, Warner Lambert called us and said, “You know, we agree with your analysis. No other agency was smart enough or honest enough to tell us, but you did. We have decided not to launch the line. Because of your honesty, though, we are going to give you some other business with us, and you won't have to compete for it.”

Of all the executives we have queried about their beliefs and values, not one has hinted that they are driven to get to the top at all costs or that diddling with the books is a reasonable tactic for achieving results. Likewise, none have stated that their work is only about increasing shareholder value. True, we might have been hearing politically correct answers, but with only a little bit of further questioning, we discovered all the leaders we interviewed have a moral compass—a set of deeply held beliefs and values—that drives their personal and professional lives. They revealed beliefs such as being honest no matter what; standing up for what is right; being responsible and accountable for their actions; caring about the welfare of those who work for them; and owning up to mistakes and failures. They told us vivid stories about how such beliefs played into the choices they made and the way they behaved. For some, it was the first time they had spoken out loud about their moral compass and its contribution to their business performance because many of those we interviewed think they shouldn't wear their beliefs on their sleeves and that discussions of moral values don't belong at work. We think work is exactly where moral values should be—and be discussed.

Why? All the leaders we interviewed recognize the importance of values to their business success. But the courageous ones who routinely communicate about their core beliefs and values—personal values as well as universal human principles they endorse—have discovered a great source of organizational energy. When a leader is explicit about what he or she believes and values, it becomes much easier for others to hold him or her accountable. Furthermore, it allows others who share those beliefs and values to say to themselves, “Hey, I agree with that. This is why I come to work, too! This is a place I can be myself and really be inspired to produce results.” When a leader is explicit about what he or she believes and values, creates a vision, strategy and goals aligned with those values, and then behaves in alignment with all of that—followers respond with deep trust of their leader.

Four years into our research and experimentation with moral intelligence tools, the new century began and with it the corporate accounting scandals that dominated its headlines. We realized it was time to go public with our findings about the relationship between morality and business performance. While business practitioners were now defensively eager to discuss compliance-based ethics, no one we knew was focusing on the personal character, principles, and moral skills that must be baked into every leader and every organization that wants to ensure long-term sustainable results. The research that forms the basis of this book is largely observational and case study-based. Over the next several years, we plan to conduct quantitative research in partnership with academic and business institutions. We will be studying the relationship between leaders' moral intelligence and the long-term financial performance of their companies. But leaders who face today's urgent business challenges can't afford to wait for further research to confirm the importance of moral intelligence to their success. Countless leaders we have coached and trained in the last few years have told us that our methods for enhancing moral intelligence are making a difference in their own performance, helping them inspire higher performance in their workforces, and contributing to better financial results.

We offer this book as a roadmap for leaders to find and follow their moral compasses. Although we believe that doing the right thing is right for its own sake, we are convinced that leaders who follow their moral compasses will find that it is the right thing for their businesses as well. This book is not about telling you what is right or wrong. It's not about helping you try to become a moral paragon. We are all imperfect, none more so than your authors. Though we all want to be our best, most ideal selves, we face daily obstacles and temptations that threaten our performance as leaders and our integrity as human beings. In this book, we hope you will find the tools to become the best leader you can be. You—and your organization—deserve nothing less.

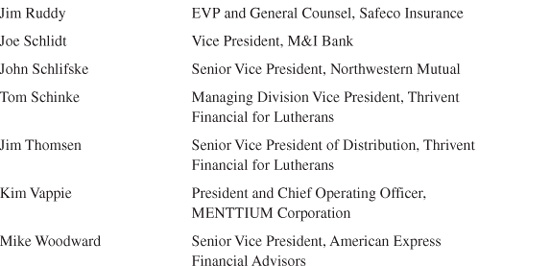

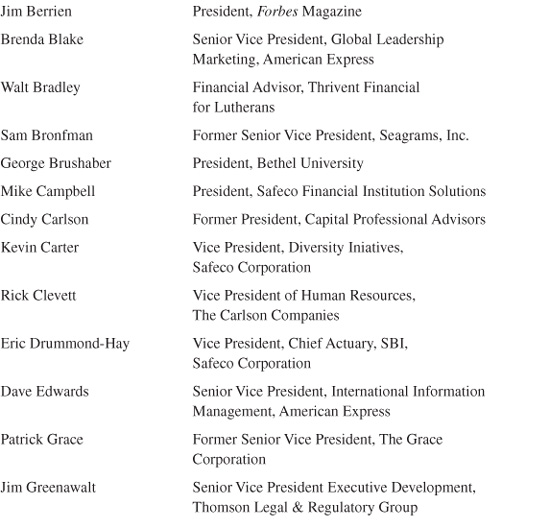

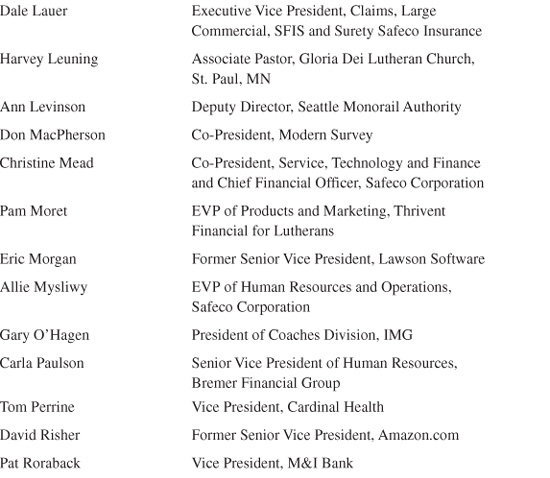

Leaders Interviewed

We are deeply indebted to the large group of leaders who contributed to our thinking and research. Our interview subjects were especially generous with their time and candid in their self-assessments.

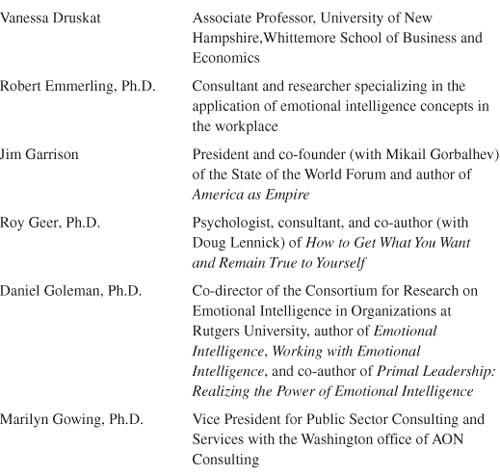

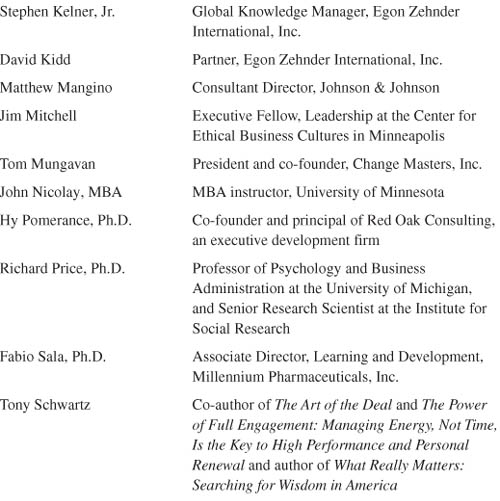

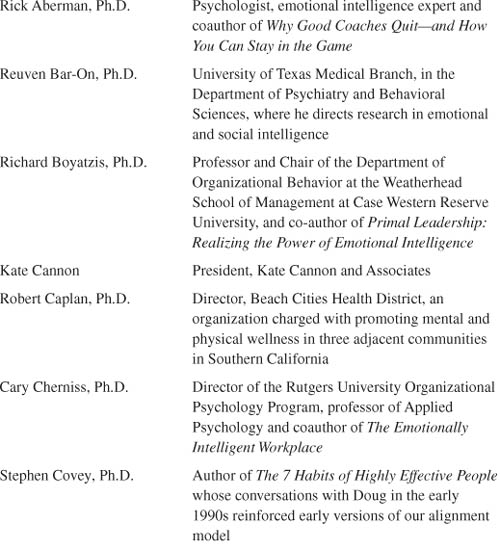

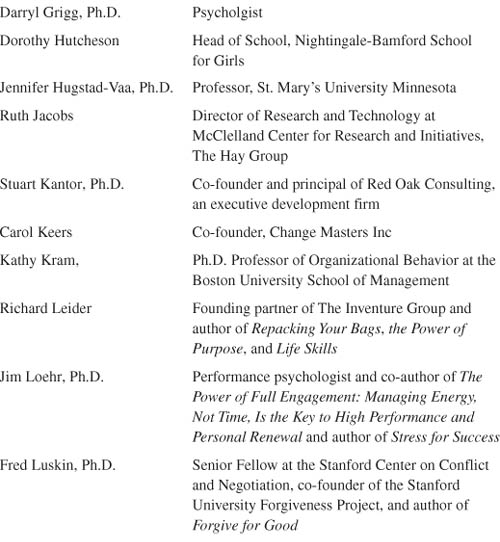

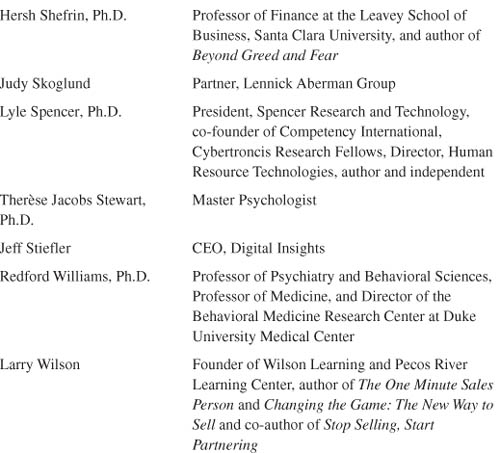

Thought Partners

We greatly appreciate our many colleagues and mentors whose input has helped sharpen our thinking about the moral dimensions of leadership. They include