Chapter 3. Your Moral Compass

As we've just seen, nearly all of us have an inborn “talent” to be moral. But talent is never enough. Think of the major league baseball teams who spend fortunes on rookies and then send them off to farm teams for a few years to hone their skills. Professional ball players begin with baseball intelligence, but they must train hard to turn their baseball intelligence into on-the-field baseball competence. So they practice technical skills such as batting or pitching, along with non-technical skills such strategy, judgment, and emotional composure. Why do they work so hard? Because they want to satisfy their goals and desires. Maybe they like winning, or money, or adulation, or they love playing the game. Successful ball players know that getting what they want means doing whatever it takes to reach their goals. In other words, the best ball players make sure that their talents, skills, and actions are aligned with their goals.

Reaching our own personal goals also requires alignment. When we decide to start a daily exercise program but never get on the treadmill, we feel uneasy because our actions are inconsistent with our goals. If we want to go on vacation, we feel good when we book the flight because we're doing something to reach our goal. Similarly, most of us want to be moral because we crave that experience of consistency between our moral values, our goals, and our actions. We call that state of moral consistency “living in alignment.”

Think of living in alignment as the interconnection of three frames:

Figure 3.1. Living in Alignment

The first frame contains your moral compass—basic moral principles, personal values, and beliefs. The second frame holds your goals. Your goals range from the lofty (your life's purpose) to the ordinary (a new house). The third frame contains your behavior, including inward thoughts, emotions, and external actions. Living in alignment means that your behavior is consistent with your goals and that your goals are consistent with your moral compass. Living in alignment keeps you on course to accomplish your life purpose and achieve the best possible performance in all your life roles.

Dale Lauer is an executive vice president with Safeco Insurance Company. Living in alignment is key to his success and longevity with his company. “The fact that I work for Safeco,” says Dale, “and that I've been here for a long time is because the company aligns well personally with my own moral code. You need to work for a company that you're aligned with or you'll have stress every day.” Dale believes that alignment was at the heart of Safeco's heralded turnaround. According to Dale, “The turnaround at Safeco is a clear financial result of practicing values of trust, honesty, loyalty, and responsibility. People on the front line, who really make the company what it is, responded because the leadership exhibited those values.” But living in alignment isn't always easy, especially when personal values conflict. Dale had to lay off a number of people he'd worked with for years, including a close friend and weekly golf partner. Balancing personal loyalty with his responsibility to his company was painful. It meant doing the right thing for Safeco's future and, at the same time, doing whatever he could to ease laid-off employees' transition to other employment.

Living in alignment may sometimes be difficult, but it doesn't require superhuman acts. It is about the day-to-day steps we take to do what we need to do to reach our goals. One of our colleagues used to avoid speaking engagements before large audiences, preferring to work with people one on one or in small groups. Eventually, he realized that he could not effectively communicate his values and beliefs if he limited himself to small group presentations. So he joined Toastmasters, the worldwide organization that helps people develop their public-speaking abilities. Our friend's desire to have a positive impact on the world led him to work on overcoming the anxiety of large group presentations.

Living in alignment is not accidental. It requires doing things on purpose and for a purpose. How to begin? Living in alignment is a two-part process: First, build your own personal alignment model:

• Moral Compass—What do you value, and what are your most important beliefs?

• Goals—What do you want to accomplish personally and professionally?

• Behavior—What actions will allow you to achieve your goals?

Then, after you've built your own alignment model and know what ideally should be in each frame, you do your best to maintain alignment among your frames.

Your Moral Compass. Your moral compass consists of principles, values, and beliefs that guide your aspirations and your actions. Everyone has one. Suppose we asked you to tell us about your moral compass. What would you say? What is the set of values that anchors you? How would you want others to think of you? Our guess is that you would describe an interesting and accomplished person, one whose actions are guided by a set of admirable values, not unlike the ones we heard earlier.

Everyone is predisposed to be moral. That doesn't mean that we always act in accordance with our values, just that it is very difficult to find someone who doesn't have positive values, even where you would least expect to find them—behind prison walls. Consider this dialogue from a personal effectiveness seminar conducted for inmates in a work/study program at a maximum security prison in Minnesota:

Seminar Leader: “How many of you know people in here that you would describe as having praiseworthy values?”

Inmates: All raise their hands.

Seminar Leader: “What do you suppose it was that you found in each other that caused you to feel this way?”

An Inmate: “I think what we found was the little boy in each other.”

This exchange is touching but not surprising if you factor in what psychologists tell us about the formation of values. Most people, assuming their brains are intact, have developed good core values by the time they reach the age of four. Nearly everyone, no matter how they actually behave, wants to be a good person. As we saw earlier, everyone with a normally functioning brain has one, and nearly everyone's moral compass bears a striking resemblance to everyone else's. That's because our moral compass is based largely on universal principles.

Embracing Universal Principles

As we discussed in the last chapter, researchers have identified several overlapping principles that they judge to be universal. You might want to use the following worksheet to chose the words that describe universal principles that you embrace.

WORKSHEET 1 Embracing Universal Principles

Please look at the list and identify the principles that you embrace—the ones that clearly resonate with you as being very important or even the most important to you in your daily life. If you feel important values are missing, feel free to add your own at the bottom of the list. Select a total of four. Then, rank the four you selected in the box to the right.

Now, list your chosen principles in rank order:

- ______________

- ______________

- ______________

- ______________

After you list the principles, check out your understanding of the principles with a trusted colleague, friend, or family member. Most of us don't make a habit of discussing universal principles in the course of a normal day, but if you do, you will discover the similarities in your and others' lists. You will validate the universal quality of the principles and will likely forge deeper connections with the people around you.

Universal Principles. When you wrote down your guiding principles, how many of these did you include in your top four—integrity, responsibility, compassion, forgiveness? The leaders studied and interviewed for this book consistently demonstrated the importance of these principles. They were at their most effective when acting in alignment with principles. When they ignored them, business results suffered. Integrity and responsibility are essential minimum requirements for effective leadership. Ed Zore, CEO of Northwestern Mutual, for example, attributes his personal success to his decision to work in a business that he thought added value to society.

Compassion and forgiveness may not be absolutely necessary, but they make the difference between a good leader who is essentially moral and a great leader who inspires exceptional performance in others. Consider the following examples of the business value of compassion.

Don MacPherson, co-president of the measurement company, Modern Survey, tells this story:

We lost a big client and went through some difficult times. One of my partners was getting married, and we were cutting salaries, including his. I knew he was facing a lot of stress. I left a note on his desk for him and his fiancée, along with a cash loan to help with the wedding expenses. They were both elated. He could have left the company during that difficult time, but he chose not to. Our business got healthy again. His salary was restored. He's a valuable part of our company to this day, and he has repaid the loan!

Lynn Sontag, CEO of MENTTIUM Corporation, which helps companies nationwide coordinate mentoring programs for women with high potential, recalls:

Everyone here knows we walk our talk. We are both passionate and compassionate and that comes through. One of our women employees has had some health problems. She is a single parent with no extended family nearby. Other employees take her to medical appointments and we all chip in to make sure her work gets done when she can't be here. Another employee's husband had cancer requiring a bone marrow transplant. We agreed to and supported her working from home for six months. We've gained tremendous loyalty from our employees because of our approach. Our workforce is fully engaged, which contributes significantly to our company's performance.

Discovering Your Values

When we grew up, we learned a set of values, those qualities or standards that parents or caregivers considered important to our well-being and that of others. Over time, we came to adopt those values as guides to our own behavior. Families vary in the weight they place on certain values. Lori Kaiser, former VP for supercomputer maker Cray, Inc., came from a large family where grandparents, great aunts and uncles, and even older siblings all got involved in teaching moral lessons. They emphasized that telling the truth was not about avoiding getting caught in a lie and that the most important persons she had to answer to were herself and her higher power. When Lori was young, her mother once caught her telling a lie. Instead of punishing her like many parents might, Lori's mother simply told her, “That's your issue, not mine! Now what are you going to do about it?” Like Lori, most of us were raised to value honesty. Families often emphasize a variety of values, such as helping others, creativity, knowledge, or wealth accumulation. We may begin by adopting our families' values, and as we mature, we often add our own. By selecting, interweaving, and prioritizing our values, we define who we are—or at least who we want to be. Just as we recognize people by their physical characteristics such as hair color, height, or the way they laugh, we also come to know people by the values they embody. As we get to know friends or colleagues, we begin to recognize what means the most to them. Do they crave excitement, care about the environment, or seek status? We evaluate others based on how well our values mesh. You might value personal time for creative work more than social activities, while I might value relationships and family time more than professional recognition. We feel comfortable around people who share our most important values and often avoid those who don't.

Unlike universal principles, which by definition apply to everyone, values are individual. They are personal. There is an especially urgent reason for identifying your most important values. Life is finite. Values help us to be selective about how we spend our precious time. Without values, how would we decide what goals are worth having? From all the opportunities that life presents us, which are most important to us? While values can help us tell right from wrong, they can also help us to decide right from right by guiding our choice from among more than one attractive option. Suppose you had a choice between a job with a high salary and a lower paying overseas assignment that offered considerable opportunities for adventure and growth. How would you decide? Now suppose that both jobs would require that you spend a considerable amount of time away from your family. What would your decision be? Neither option is necessarily right or wrong in itself. To make the right decision, you would have to weigh the relative importance of personal values such as wealth, personal development, adventure, and family.

The Morality of Values

Not all values are created equal, as in the previous example. Without some context, values are neither moral nor immoral. It is only when we need to make decisions that have moral consequences that values take on moral significance. Being moral means more than honoring your personal value system. Because we choose our values, it is possible that personal values may be out of alignment with the principles. Try to imagine the contents of Osama bin Laden's moral compass. No one would deny that bin Laden has a strong value system, one that probably includes some admirable beliefs. But his willingness to harm innocent victims, including members of his own Islamic faith, in pursuit of his values, violates the universal principle of compassion. Osama bin Laden “walks his talk;” that is, his goals and actions are consistent with his values, but some of his values violate our universal moral compass. We don't have to travel half-way around the world for examples of values misalignment, as demonstrated in 2004 when several bankrupt U.S. airline companies used Chapter 11 to skip mandatory pension contributions, putting retirees' livelihoods in jeopardy.

When we make a decision that does not have any particular moral significance, as in deciding where to go on vacation, we might indulge our desire for adventure without a second thought. But when we are making a decision that involves others, as is the case when considering a career move that would affect family members, the priorities we assign to our values must be consistent with universal principles. In that instance, we must honor the principle of responsibility. We may realize that our desire for adventure, growth, or more money would come at the cost of our responsibility to family.

Identifying Your Values. As with every element of effective leadership, good decision-making requires clarity about your personal values. You can use the following worksheet to better understand your values and their relative importance in your life.

WORKSHEET 2: Identifying Your Core Values

Please circle the number at the left of each personal value you believe to be one of your core values. If you feel important values are feel important values are missing, feel free to add your own at the bottom of the list.

Now, select five you believe to be your most important core values and list them here:

- ._____________

- ._____________

- ._____________

- ._____________

- ._____________

This short list of five most important values probably represents the aspects of life you hold most dear. That does not mean you will always behave in ways that are consistent with your ideal values. But if you consistently behave in ways that are in conflict with what you say you value, it may be useful to reexamine your values statement. Do you espouse a value because it is politically correct in your organization or because you were brought up to believe in it?

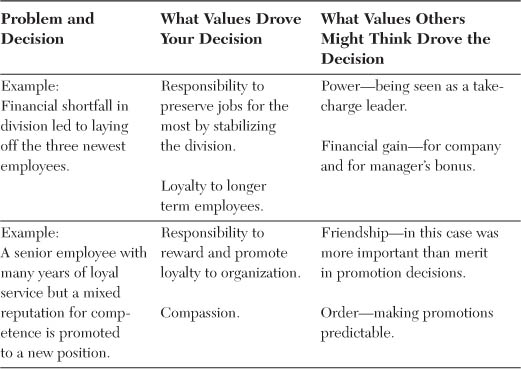

What Your Decisions Reveal About Your Values. Sometimes, we don't actually value what we say we do. If, over time, you find yourself behaving inconsistently with your espoused values, you have a choice. You can learn to better align your behavior with your values by developing your moral and emotional competencies, or you may simply accept that you value some things that you did not realize were important to you. Either path is fine, as long as your actions don't violate the universal principles.

To find out what your outward behavior can tell you about your values, keep a running log of all your decisions over the course of a few weeks. For each decision:

• Write down the values that influenced your decision.

• Ask yourself, “If people who did not know my inner motivations saw the outcome of this decision, what value or values would they think this decision reflected?

This exercise can give you some insight into personal motivations that you might not have admitted to yourself before. Consider whether the values others might attribute to your decision may actually have some bearing on your choices.

Uncovering Values Conflicts. After you identify what you value, ideally and really—look at your list of values and compare it with the universal principles. To ensure that your values are consistent with principles, ponder questions like these:

• Is my desire to achieve financial results so strong that I behave as if the end justifies the means?

• Does my desire for high achievement lead me to lack compassion for an employee whose family crisis takes him away from work at a critical time?

• Does my need for economic security discourage me from speaking out with integrity about an unethical corporate practice?

If you accept that universal principles universally apply, you must—as a morally intelligent leader—reprioritize your values in line with the principles. We are not saying that you should not value what you value. But in some cases, it will be important to find a way to honor your values while upholding principles. You can honor both principles and personal values when you look for answers to questions such as, “How can I arrange my financial affairs so that I am protected if my ethical position gets me fired? Or, “How can I creatively allocate resources to preserve or improve group productivity while an employee is out on leave?”

It should be clear by now that values can be applied in a morally bad, neutral, or positive way. We are not encouraging you to abandon your values in favor of certain values that may have a more obvious moral veneer.

Beliefs

Beliefs are the third component of our guidance system. For each of us, our beliefs are the “executive summary” of our individual world view. Beliefs represent our self-understanding about what we think is important and how we think of ourselves in relation to the outer world. They are the condensed version of our moral compass. Beliefs capture our larger list of principles and values in a streamlined form that is easier to communicate. Beliefs are the language we use to describe our values and our understanding of principles to ourselves and others. They connect our understanding of principles with our choice of values. You can't really know what your values are unless you can make a statement about what you believe.

Identifying Your Beliefs

You probably have 10,000 beliefs about yourself, your world, and human nature. But most people have a relatively short list of beliefs that they hold as their “convictions”—beliefs they use to guide decision-making when the going gets rough. Many of these might even operate at an unconscious level most of the time, but with a little thought, most people can bring them up to the surface. What do you believe? You can use Worksheet 3 to record your “top ten” beliefs.

WORKSHEET 3 My Top Ten Beliefs

Please take a few minutes to record your “top ten” beliefs in the following spaces. Remember…try to focus on your beliefs about yourself, your world, and human nature.

By this point, you have identified the key elements of your moral compass. You have chosen the universal principles you embrace, you have articulated your values, and you have summarized your beliefs. Understanding your moral compass is essential to effective decision-making. Living in alignment means that you hold yourself accountable for decisions consistent with your moral compass. But before you take action, you need to understand your goals and wants.

Goals

Scientists who study behavior tell us that humans have an innate need to make sense out of our lives. We constantly develop theories to explain why things happen as they do.

Say you see a cloud-like substance billowing out of a window. Maybe you hypothesize that something is on fire. If you're an astute observer, you might notice that the substance is pale and there is no smell of smoke and realize that it's actually steam. Whether you're right or wrong about the nature and origin of the billowy substance, in both cases you are trying to create meaning out of your observations. We have a similar need to attribute meaning to our lives. How do our day-to-day events combine to create a coherent whole? What is the point of doing what we do? If we can begin to answer those questions, we have the beginning of our highest goal—our life's purpose. Not everyone develops and follows a life purpose. People who were injured or severely neglected or abused might lack the capacity to formulate a meaningful purpose. But most of us are hungry to make sense out of our lives, so we create goals. Everyone's life purpose is distinctively theirs, but each must be consistent with universal principles of integrity, responsibility, compassion, and forgiveness. Albert Schweitzer once said, “I don't know what your destiny will be, but one thing I do know: the only ones among you who will be really happy are those who have sought and found how to serve.” Oprah Winfrey, who created one of the wealthiest entertainment empires in the United States, says this about purpose: “I've come to believe that each of us has a personal calling that's as unique as a fingerprint—and that the best way to succeed is to discover what you love and then find a way to offer it to others in the form of service, working hard, and also allowing the energy of the universe to lead you.”1 So take a few minutes to reflect on your life purpose using the following worksheet.

WORKSHEET 4 My Purpose2

Be patient. The discovery of purpose can take some time. But when you come to “feel it,” you'll know it was worth the wait.

These questions might help:

- What are my talents?

- What am I passionate about?

- What do I obsess about, daydream about?

- What do I wish I had more time to put energy into?

- What needs doing in the world that I'd like to put my talents to work on?

- What are the main areas in which I'd like to invest my talents?

- What environments or settings feel most natural to me?

- In what work and life situations am I most comfortable expressing my talents?

Now, draft your purpose statement:

What Do You Want for Yourself? WDYWFY (pronounced “widdy wiffy”) is a process developed to help people clarify their goals.3 WDYWFY is an acronym for “What Do You Want for Yourself?” First, let us dispose of a myth. Wanting is ok. Being moral does not mean that you must be an anti-materialistic saint. Wanting is part of human nature. Being human means that you are a wanting being. In their book, Driven, Harvard Business School professors Paul Lawrence and Nitin Nohria argue that fulfillment in life depends on finding ways to satisfy our inborn instinctual drives.4 It's the way we satisfy our instinctual drives that makes the difference between being morally intelligent and morally impaired. For example, as humans, our sex drive is instinctual, but there's a big difference between consensual love-making and date rape.

Getting what we want is good. But if we don't channel our instinctual drives, we get in trouble. That is why goal-setting is vital to living in alignment. Without goals, it's hard to create meaning out of our actions. Without goals, our ability to fulfill our life's purpose would be a matter of chance. Setting deliberate goals allows us to satisfy our wants in a way that is aligned with our moral compass.

Not only does your goal frame help you satisfy your wants within a moral framework, paying attention to goals also increases the odds that you will actually accomplish what you desire. If you don't work on your goal frame, there is a random occurrence of achieving your goals. Career expert David Campbell made that point famously in his book If You Don't Know where You're Going, You'll Probably End Up Somewhere Else.5 Apparently, it's not enough to have a set of goals in your head. You will boost your ability to achieve your goals when you write down your goals and your plans to achieve them. Why do written goals have such a positive impact? The most basic reason is that we tend to forget things. The physical process of writing helps our brain retain and recall the things we want to accomplish. When we write down goals, we have an opportunity to reflect carefully on what we really want and consider the best ways to accomplish them. When we record our goals, we can use our list as a reminder to stay on track. The process of writing down goals enhances our commitment and capacity to be responsible for the choices we make. We have all known of highly intelligent individuals who never lived up to their potential. Similarly, moral intelligence is wasted unless you use it in service of positive results, and goal setting will help you leverage the power of your moral intelligence to have a positive impact on your organization and the world.

Why Leaders Love Goals

Every effective leader we know has crystal clear goals. Goals are crucial to effective leadership because they move you beyond awareness or good intentions to specific actions. Effective leaders accept responsibility for their choices by “getting on the record” with their goals. Effective leaders have goals that they really care about. They also encourage their followers to develop personally satisfying goals. One of the most powerful motivational tools of a good leader is to show that you care about the wants and goals of the people who work with you.

Employees with that rare boss who shows genuine interest in their goals—and who spends time helping them chart a course to reach those goals—respond with loyalty and commitment. Brian Heath, General Sales Manager of American Express Financial Advisors, is a body builder who does a mean impression of Arnold Schwarzenegger. Brian's sheer size and dominating demeanor fool some people into thinking he's nothing more than a tough guy. But Brian is also a people builder. When Brian was a regional vice president, he spent a lot of time listening to his employees. He learned that they wanted to be very successful but that many of them lacked confidence that they could achieve their goals. He learned a lot about what bothered them and how their fears got in the way of their performance. Brian decided that his employees needed him to help them overcome their insecurities and demonstrate confidence in their ability to accomplish their goals. So he decided on a regional goal that would reflect the ambitions the advisors had for themselves: They would set a goal that would require above average performance from everybody. Going forward, they would expect the average performance of all the division's advisors to equal the current level of performance of the top five percent. Brian presented it to his group in a speech titled, “Our Ridiculous Goal”—ridiculous because the bar was set so high. But Brian knew that all his advisors wanted to be top performers, and in the end they achieved their ridiculous goal.

Your Goals

What exactly do you want for yourself? What are your goals? The majority of us want to play the roles we have in life well. Most people who are parents want to be good at it. Even terrible parents want to be good at it. There are very few of us who don't care about how we perform. How many of you want to be part of a family that you are proud of? How many of you want to be part of an organization that you are proud of? What do you have to do to accomplish that?

Put It in Writing

Whether you are developing new goals or reinforcing long-standing goals, writing your goals down here will make them more real. Keep in mind that there are two kinds of goals. Some goals are a state of being goal, such as “I have three children. I want to be a good father now.” Another type of goal is a future based goal, for example, “I want to retire within five years” or “I want to lose weight.” We recommend that you include goals of both types.

WDYWFY (What Do You Want For Yourself?) Follow these steps to decide on the goals that are most important to you:

Step 1: Goal Identification. Decide what your top three to five life goals are and record them on Worksheet 5.

WORKSHEET 5 My Most Important Life Goals

- _______________________________________________________________

- _______________________________________________________________

- _______________________________________________________________

- _______________________________________________________________

- _______________________________________________________________

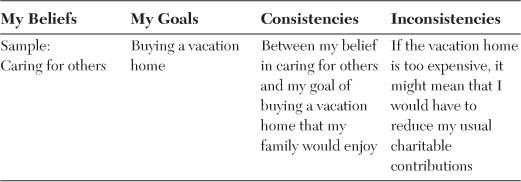

Step 2: Goal Alignment. Think about your top long-term goals. How well do your goals fit with your principles, values, and beliefs?

You don't need to abandon any goal that would make you wildly happy. But you will find that your overall happiness and effectiveness will be enhanced if each of your goals is strongly aligned with your moral compass.

Behavior

The behavior frame puts the “living” in “living in alignment.” Your behavior frame represents what you actually do, including your thoughts, emotions, and outward actions. Your behavior frame is what inspires people to follow you as a leader. People will not know you as a moral leader unless you communicate what you stand for—and act accordingly. When we act stupid, we give ourselves the benefit of the doubt, but others might not. So keeping your behavior in alignment with your moral compass and goals is essential for effective leadership.

Thoughts. What makes thoughts part of our behavior frame? Psychologists recognize thoughts as a form of cognitive behavior. They can't be seen by the outside observer, but like outward actions, they are within our control. We can act on them—we can change what we think. Most important, thoughts profoundly affect your emotions and your outward behavior. In a later chapter you will explore in greater detail about how to manage thoughts in ways that keep you in alignment.

Emotions. Everyone has them, even the most rational and composed of us. Emotions are neither good nor bad. They are simply emotions. But because strong emotions, whether positive or painful, can get in the way of effective behavior, emotions must be managed. The most effective leaders know how to regulate their own and others' emotional responses in a way that promotes a positive and high-performing work environment. If leaders lack emotional control or insight into the emotional needs of their followers, the work environment suffers. Earlier in her career, when MENTIUM CEO Lynn Sontag was a senior leader in executive development at a Fortune 100 company, she once made the mistake of transferring a call from an irate executive spouse to her boss. The caller, who had considerable clout, was having a temper tantrum about something that the organization wouldn't as a matter of policy give her. Lynn realized too late that she should have prepared her boss for the call so he wouldn't get stuck in a political bind. She still has vivid memories of his reaction and the impact on her subsequent performance:

I can visualize the whole thing. My office was kitty corner from the executive director, and I could see his expressions as he talked to her, and it was pretty visual. His door was closed, but I could see him through his window, and I knew where he was heading as soon as he opened the door. He blew up in front of me and everyone else around. The next day he calmed down, and we walked through it and processed it so that it wouldn't happen again. We got through it, but I was derailed on a personal level for a long time. I still had to work with the woman for another year and a half. It took me more than a couple months to let go. It hit me right where my confidence was. I didn't trust my own judgment, and I became unwilling to make decisions without checking with a lot of people first.

Actions. We all know they speak louder than words. Having a moral compass and admirable goals is worthless unless we do what it takes to make them real. In fact, failure to act in concert with our values and goals is worse than worthless. It does us harm. It makes us untrustworthy. Whom do we trust? People who do what they say they will do. People we can count on to behave with integrity and compassion.

In Search of Alignment. Now that you see the canvas inside each of your frames, how do you keep your frames aligned? In the next chapter, we turn to the skills that connect our frames and the obstacles that interfere with living in alignment.