Chords

In This Chapter

![]()

- Understanding major, minor, diminished, and augmented triads

- Extending chords to sevenths, ninths, and beyond

- Creating altered, suspended, and power chords

- Inverting the chord order

- Writing chords into your music

Lesson 6, Track 41

Lesson 6, Track 41

More often than not, music is more than a single melodic line. Music is a package of tones, rhythms, and underlying harmonic structure. The melody fits within this harmonic structure, is dependent on this harmonic structure, and in some cases dictates the harmonic structure.

The harmonic structure of a piece of music is defined by a series of chords. A chord is a group of notes played simultaneously, rather than sequentially (like a melody). The relationships between the notes—the intervals within the chord—define the type of chord; the placement of the chord within the underlying key or scale defines the role of the chord.

This chapter is all about chords—and it’s a long one, because there are many, many different types of chords. Don’t let all the various permutations scare you off, however; at the core, a chord is nothing more than single notes (typically separated by thirds) played together. It’s as simple as that. If you can play three notes at the same time, you can play a chord.

This chapter, then, shows you how to construct many different types of chords, with a particular emphasis on the type of harmonic structure you find in popular music. (This is important; the study of harmony in classical music is much more involved, with a slightly different set of rules.) And, when you’re done reading this chapter, you can find a “cheat sheet” to all the different chords online at idiotsguides.com/musictheory, a quick yet comprehensive reference to every kind of chord imaginable—in every key!

Forming a Chord

Okay, here’s the formal definition: a chord is a combination of three or more notes played together.

Let’s do a little exercise: sit down at the nearest piano and put your right thumb on one of the white keys. (It doesn’t matter which one.) Now skip a key and put another finger on the third key up. Skip another key and put a third finger on the fifth key up from the first. You should now be pressing three keys, with an empty key between each finger. Press down and listen—you’re playing a chord!

Basic chords consist of just three notes, arranged in thirds, called a triad. The most common triads are constructed from notes plucked from the underlying scale, each note two steps above the previous note. So, for example, if you want to base a chord on the tonic of a scale, you’d use the first, third, and fifth notes of the scale. (Using the C Major scale, these notes would be C, E, and G.) If you want to base a chord on the second degree of a scale, use the second, fourth, and sixth notes of the scale. (Still using the C Major scale, these notes would be D, F, and A.)

Building a three-note triad.

Within a specific chord, the first note is called the root—even if the chord isn’t formed from the root of the scale. The other notes of the chord are named relative to the first note, typically being the third and the fifth above the chord’s root. (For example, if C is the chord’s root, E is called the third and G is called the fifth.) This is sometimes notated 1-3-5.

NOTE

The notes of a chord don’t always have to be played in unison. You can play the notes one at a time, starting (usually, but not always) with the bottom note. This is called arpeggiating the chord, and the result is an arpeggio.

Let’s go back to the piano. Putting your fingers on every other white note, form a chord starting on middle C. (Your fingers should be on the keys C, E, and G.) Nice sounding chord, isn’t it? Now move your fingers one key to the right, so that you’re starting on D. (Your fingers should now be on the keys D, F, and A.) This chord sounds different—kind of sad, compared to the happier C chord.

You’ve just demonstrated the difference between major and minor chords. The first chord you played was a major chord: C Major. The second chord was a minor chord: D minor. As with major and minor scales, major and minor chords sound different to the listener, because the intervals in the chords are slightly different.

In most cases, the type of chord is determined by the middle note: the third. When the interval between the first note and the second note is a major third—two whole steps—you have a major chord. When the interval between the first note and the second note is a minor third—three half steps—you have a minor chord.

It’s no more complex than that. If you change the middle note, you change the chord from major to minor.

Read on to learn all about major and minor chords—as well as some other types of chords that aren’t quite major and aren’t quite minor.

WARNING

You should always spell a triad using every other letter. So D♭-F-A♭ is a correct spelling (for a D♭ Major chord), but the enharmonic spelling of C♯-F-A♭ is wrong.

Major Chords

A major chord consists of a root, a major third, and a perfect fifth. For example, the C Major chord includes the notes C, E, and G. The E is a major third above the C; the G is a perfect fifth above the C.

Here’s a quick look at how to build major chords on every note of the scale:

Major triads.

There are many different ways to indicate a major chord in your music, as shown in the following table.

Notation for Major Chords

Major Chord Notation |

Example |

Major |

C Major |

Maj |

C Maj |

Ma |

C Ma |

M |

CM |

Δ |

CΔ |

In addition, just printing the letter of the chord (using a capital letter) indicates that the chord is major. (So if you see C in a score, you know to play a C Major chord.)

TIP

When you play a chord based on the tonic note of a major scale or key, that chord is always a major chord. For example, in the key of C, the tonic chord is C Major.

Minor Chords

The main difference between a major chord and a minor chord is the third. Although a major chord utilizes a major third, a minor chord flattens that interval to create a minor third. The fifth is the same.

In other words, a minor chord consists of a root, a minor third, and a perfect fifth. This is sometimes notated 1-♭3-5. For example, the C minor chord includes the notes C, E♭, and G.

Here’s a quick look at how to build minor chords on every note of the scale:

Minor triads.

There are many different ways to indicate a minor chord, as shown in the following table.

Notation for Minor Chords

Minor Chord Notation |

Example |

minor |

C minor |

min |

C min |

mi |

C mi |

m |

Cm |

Diminished Chords

A diminished chord is like a minor chord with a lowered fifth. It has a kind of eerie and ominous sound. You build a diminished chord with a root note, a minor third, and a diminished (lowered) fifth. This is sometimes noted 1-♭3-♭5.

TIP

In this and other chord charts in this book, the accidentals apply only to the specific chord; they don’t carry across to successive chords.

For example, the C diminished chord includes the notes C, E♭, and G♭.

Here’s a quick look at how to build diminished chords on every note of the scale:

Diminished triads.

NOTE

Note the double flat on the fifth of the E♭ diminished chord.

There are many different ways to indicate a diminished chord, as shown in the following table.

Notation for Diminished Chords

Diminished Chord Notation |

Example |

diminished |

C diminished |

dimin |

C dimin |

dim |

C dim |

° |

C° |

Augmented Chords

An augmented chord is like a major chord with a raised fifth; thus an augmented chord consists of a root, a major third, and an augmented (raised) fifth. This is sometimes notated 1-3-♯5.

For example, the C augmented chord includes the notes C, E, and G♯.

Here’s a quick look at how to build augmented chords on every note of the scale:

Augmented triads.

NOTE

Did you spot the double sharp on the fifth of the B augmented chord in the illustration of augmented chords?

There are many different ways to indicate an augmented chord, as shown in the following table.

Notation for Augmented Chords

Augmented Chord Notation |

Example |

augmented |

C augmented |

aug |

C aug |

+ |

C+ |

Although it’s important to learn about diminished and augmented chords, you won’t run into too many of them, especially in popular music. If you base the root of your chord on the notes of a major scale, as you’ll learn in Chapter 10, only the seventh degree triad forms a diminished chord. (Triads based on the other degrees of the scale form major or minor chords.) There is no augmented chord found on any degree of the major scale.

Chord Extensions

Chords can include more than three notes. When you get above the basic triad, the other notes you add to a chord are called extensions.

Chord extensions are typically added in thirds; so the first type of extended chord is called a seventh chord because the seventh is a third above the fifth. Next up would be the ninth chord, which adds a third above the seventh, and so on.

Chord extensions are nice to know, but you can simplify most pieces of music to work with just the basic triads. The extended notes add more color or flavor to the sound, kind of like a musical seasoning. Like a good meal, what’s important is what’s underneath—and you can always do without the seasoning.

So if you see a piece of music with lots of seventh and ninth chords, don’t panic—you can probably play the music without the extensions and still have things sound okay. Of course, for the full experience, you want to play the extended chords as written. But remember, the basic harmonic structure comes from the base triads; not from the extensions.

That said, it helps to have a full understanding of extended chords, just as a good chef must have a full understanding of all the different seasonings at his or her disposal. That means you need to know how to build extended chords, so you can throw them into the mix when necessary.

Sevenths

The seventh chord is the most common chord extension—in fact, it’s so common that some music theorists categorize it as a basic chord type, not as an extension. In any case, you need to be as familiar with seventh chords as you are with triads. They’re that important.

Creating a seventh chord within a specific key or scale is normally as simple as adding another third on top of the fifth of the base triad. This gives you a 1-3-5-7 structure—the equivalent of playing every other note in the scale.

There are actually three basic types of seventh chords: major, minor, and dominant. Major and minor seventh chords are kind of sweet sounding; the dominant seventh chord has its own internal tension.

The dominant seventh chord—sometimes just called the “seventh” chord, with no other designation—takes a major triad and adds a minor seventh on top. In other words, it’s a major chord with a lowered seventh; the chord itself consists of a root, major third, perfect fifth, and minor seventh. This is sometimes notated 1-3-5-♭7.

For example, a C7 chord includes the notes C, E, G, and B♭.

The dominant seventh chord is an especially important—and frequently used—extension, as this is what you get if you play a seventh chord based on the fifth (dominant) tone of a major scale. As you’ll learn in Chapter 10, the dominant chord is frequently used to set up the tension leading back to the tonic chord; when you add a seventh to the dominant triad (with its mix of major triad and minor seventh), you introduce even more tension to the music. So when you want to get back home to the tonic, you set it up with a dominant seventh chord. (Although it’s possible, of course, to also form dominant seventh chords on any note of the scale—it’s not limited to the fifth tone.)

Here’s a quick look at how to build dominant seventh chords on every note of the scale:

Dominant seventh chords.

There’s really only one way to notate a dominant seventh chord: by placing a single 7 after the name of the chord. For example, you notate a C dominant seventh chord like this: C7.

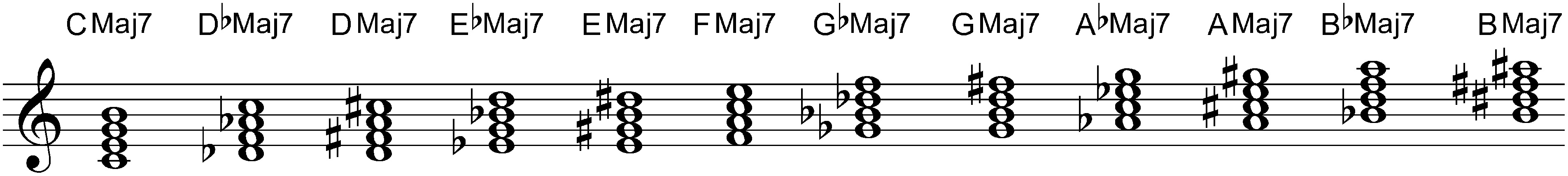

Major Sevenths

The major seventh chord takes a standard major chord and adds a major seventh on top of the existing three notes. This gives you a chord consisting of a root, major third, perfect fifth, and major seventh. For example, a C Major 7 chord includes the notes C, E, G, and B.

Here’s a quick look at how to build major seventh chords on every note of the scale:

Major seventh chords.

There are several ways to indicate a major seventh chord, as shown in the following table.

Notation for Major Seventh Chords

Major Seventh Chord Notation |

Example |

Major 7 |

C Major 7 |

Maj7 |

C Maj7 |

M7 |

CM7 |

Δ7 |

CΔ7 |

Minor Sevenths

The minor seventh chord takes a standard minor chord and adds a minor seventh on top of the existing three notes. This gives you a chord consisting of a root, minor third, perfect fifth, and minor seventh. (This is sometimes notated 1-♭3-5-♭7.)

For example, a C minor 7 chord includes the notes C, E♭, G, and B♭.

Here’s a quick look at how to build minor seventh chords on every note of the scale:

Minor seventh chords.

There are several ways to indicate a minor seventh chord, as shown in the following table.

Notation for Minor Seventh Chords

Minor Seventh Chord Notation |

Example |

minor 7 |

C minor 7 |

min7 |

C min7 |

m7 |

Cm7 |

When I said there were three basic types of seventh chords, I left the door open for other types of less frequently used seventh chords. Indeed, you can stick either a minor or a major seventh on top of any type of triad—major, minor, augmented, or diminished—to create different types of seventh chords.

For example, a major seventh stuck on top of a minor triad creates a minor major seventh chord. (That is, the base chord is minor, but the seventh is major.) This is notated 1-♭3-5-7; a C minor Major 7 chord would include the notes C, E♭, G, and B (natural).

Other types of seventh chords.

A minor seventh on top of a diminished triad creates what’s called a half-diminished seventh chord, like this: 1-♭3-♭5-♭7. It’s sometimes notated as a minor 7 with a flatted fifth. (This is the chord you get if you play a seventh chord based on the seventh tone of a major key.) If you want a full diminished seventh chord, you need to double-flat the seventh, like this: 1-♭3-♭5-♭♭7.

Put a minor seventh on top of an augmented triad and you get an augmented seventh chord, like this: 1-3-♯5-♭7. A major seventh on top of an augmented triad creates a major seventh chord with a raised fifth (♯5), like this: 1-3-♯5-7 … and so on.

Other Extensions

Although the seventh chord is almost as common as an unadorned triad, other chord extensions are less widely used. That doesn’t mean you don’t need to bother with them; when used properly, sixths and ninths and other extended chords can add a lot to a piece of music.

Let’s look, then, at the other extensions you can use to spice up your basic chords.

Sixths

I said previously that all chords are based on notes a third apart from each other. There’s an important exception to that rule: the sixth chord. With a sixth chord (sometimes called an added sixth chord), you start with a basic triad; then add an extra note a second above the fifth—or a sixth above the root. You can have major sixth and minor sixth chords, as well as sixths above diminished and augmented triads, as shown in the following figure:

Different types of sixth chords.

NOTE

Later in this chapter, you’ll learn about chord inversions, where the order of the notes in a chord is changed. Interestingly, a sixth chord can be viewed as nothing more than the first inversion of a seventh chord. For example, the C Major 6 chord (C E G A) contains the same notes as the A minor 7 chord (A C E G), just in a different order. For that reason, you sometimes might see sixth chords notated as seventh chords with a separate note (the third) in the bass. (C Major 6 could be notated like this: Am7/C.) This is a little advanced—come back to this sidebar after you’ve read the section on inversions. It’ll make sense then.

Ninths

A ninth chord adds another third on top of the four notes in the seventh chord. That makes for five individual notes; each a third apart. You can have ninth chords based on both major and minor triads, with both major and minor sevenths. Here’s just a smattering of the different types of ninth chords you can build:

Different types of ninth chords.

Seventh, ninth, and eleventh chords see frequent use in modern jazz music, which often employs sophisticated harmonic concepts.

NOTE

When you get up to the ninth chord, you assume that the chord includes both the underlying triad and the seventh.

An eleventh chord adds another note a third above the ninth, for six notes total: 1-3-5-7-9-11. You can set an eleventh on top of any type of triad, along with all sorts of seventh and ninth variations—although the most common eleventh chord always uses the unchanged note from within the underlying key or scale.

As with the ninth chord, you have to make a few assumptions with the eleventh chord. You have to assume the underlying triad, of course, but you also have to assume the presence of both the seventh and the ninth.

Different types of eleventh chords.

It’s also possible to construct a thirteenth chord by adding another third above the eleventh. But that’s as high as you can go because the new note for the next chord up—the fifteenth chord—is exactly two octaves up from the chord root. There’s no point in calling it a new chord when all you’re doing is doubling the root note.

Altered, Suspended, and Power Chords

To ensure that you have a comprehensive background in chord theory, there are three other chord types you need to know about. These are variations on the basic chord types that crop up from time to time—and can help you notate more complex musical sounds.

Altered Chords

When you get into seventh and ninth and eleventh chords, you run into the possibility of a lot of different variations. It’s math again; the more notes in a chord, the more possible combinations of flats and sharps and such you can create.

This is why we have something called altered chords. Altered chords take standard, easy-to-understand chords and alter them. The alteration—a lowered fifth, perhaps, or maybe an added ninth—is typically notated in parentheses, after the main chord notation. (By the way, don’t confuse altered chords with the altered bass chords discussed in Chapter 16. The names are similar but they’re completely different beasts.)

For example, let’s say you wanted to write a C Major seventh chord, but with a lowered fifth. (I know … that’s a really weird-sounding combination.) To notate this, you start with the basic chord—CM7—and add the alteration in parentheses, like this: CM7(♭5). Anyone reading this chord knows to start with the basic chord and then make the alteration shown within the parentheses.

Here’s another example: let’s say you have a C minor chord and want to add the ninth but without adding the seventh. Now, if you wanted to include the seventh, you’d have a Cm9 chord, which is relatively standard. But to leave out the seventh takes a bit more planning. Again, you start with the underlying triad—in this case, Cm—and make the alteration within parentheses, like this: Cm(add9). Anyone reading this chord knows to play a C minor triad and then add the ninth—not to play a standard Cm9 chord.

The difference between a ninth chord and a triad with an added ninth.

TIP

Added notes can be notated by the word add plus the number, or just the number—within parentheses.

There are an endless number of possibilities you can use when working with altered chords. You can even include more than one variation per chord—all you have to do is keep adding the variations onto the end of the chord notation. Just remember to start with the base chord and make your alterations as clear as possible. (And, if all else fails, you can write out the notes of the chord on a staff—just to make sure everybody understands.)

Suspended Chords

We’re so used to hearing a chord as a 1-3-5 triad that any change to this arrangement really stands out like a sore thumb to our ears. (Not that you should put your thumbs in your ears, but you know what I mean.) This is what makes a suspended chord so powerful, especially when used properly.

A suspended chord temporarily moves the normal major third of a major chord up a half step to a perfect fourth. This suspension of the second note of the triad is so wrong to our ears, we want to hear the suspension resolved by moving the second note down from the fourth to the third—as quickly as possible.

For example, a C suspended chord includes the notes C F G—instead of the C E G of C Major. This sets up an incredible tension, as the fourth (F) sounds really out of place; your ears want the F to move down to the E to create the more soothing C Major triad.

In fact, most often you do resolve suspended chords—especially at the end of a musical phrase. You can use the suspended chord to set up the desired end-of-phrase tension, but then quickly resolve the suspended chord to the normal major chord, like this:

Resolving a suspended chord—the F in the first chord drops down to the E in the final chord.

NOTE

As you can see from the example, you notate a suspended chord with the phrase sus4, or more simply sus.

The resolution from the perfect fourth to the major third is just a half-step movement, but that little half step makes a world of difference; until you make the move, you’re sitting on the edge of your seat waiting for that incredible tension to resolve.

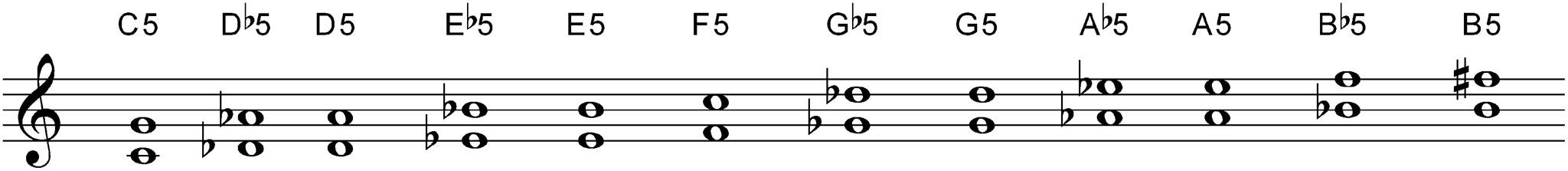

Power Chords

If you want a really simple chord, one with a lot of raw power, you can play just the root and the fifth, leaving out the third. This type of chord is called a power chord; it is noted by adding a “5” after the chord note. (For example, a G power chord is notated G5, and includes only the notes G and D.) Power chords are used a lot by guitarists in certain types of popular music, in particular the hard rock and heavy metal genres.

NOTE

In classical music theory, a power chord is called an open fifth, and is technically an interval, not a chord.

Here’s one bad thing about power chords: if you use a bunch of them in a row, you create something called parallel fifths. As you’ll learn, parallel fifths are frowned upon, especially in classical music theory. So use power chords sparingly and—if at all possible—not consecutively.

Power chords, up and down the scale.

Inverting the Order

Although it’s easiest to understand a chord when the root is on the bottom and the fifth is on the top, you don’t have to play the notes in precisely this order. Chords can be inverted so that the root isn’t the lowest note, which can give a chord a slightly different sound. (It can also make a chord easier to play on a piano, when you’re moving your fingers from chord to chord; inversions help to group the notes from adjacent chords closer together.)

When you rearrange the notes of a chord so that the third is on the bottom (3-5-1), you form what is called the first inversion. (Using a C Major chord as an example, the first inversion is arranged E G C.) The second inversion is where you put the fifth of the chord on the bottom, followed by the root and third (5-1-3). (Again using C Major as an example, the second inversion is arranged G C E.) The standard triad form, with the root on the bottom, is called the root inversion.

The first and second inversions of a C Major chord.

If you’re working with extended chords, there are more than two possible inversions. For example, the third inversion of a seventh chord puts the seventh in the bass; the fourth inversion of a ninth chord puts the ninth in the bass.

The particular order of a chord’s notes is also referred to as that chord’s voicing. You can specify a voicing without writing all the notes by adding a bass note to the standard chord notation. You do this by adding a slash after the chord notation, and then the name of the note that should be played on the bottom of the chord.

For example, if you want to indicate a first inversion of a C Major chord (normally C E G, but E G C in the first inversion), you’d write this: C/E. This tells the musician to play a C Major chord, but to put an E in the bass—which just happens to be the first inversion of the chord. If you wanted to indicate a second inversion (G C E), you’d write this: C/G. This tells the musician to play a C Major chord with a G in the bass.

You also can use this notation to indicate other, nonchord notes to be played in the bass part. For example, Am7/D tells the musician to play an A minor seventh chord, but to add a D in the bass—a note that doesn’t exist within the A minor seventh chord proper.

An A minor seventh chord with a D in the bass—not your standard seventh chord.

WARNING

Don’t confuse the chord/bass notation with the similar ![]() (like a fraction with a horizontal divider, as opposed to the chord/bass diagonal slash). The

(like a fraction with a horizontal divider, as opposed to the chord/bass diagonal slash). The ![]() notation tells a musician—typically a pianist—to play one chord over another. For example, if you see

notation tells a musician—typically a pianist—to play one chord over another. For example, if you see ![]() you should play a Cm chord with your right hand, and a Dm chord with your left.

you should play a Cm chord with your right hand, and a Dm chord with your left.

Adding Chords to Your Music

When you want to indicate a chord in your written music, you add the chord symbol above the staff, like this:

Write the chord symbol above the staff.

The chord applies in the music until you insert another chord. Then the new chord applies—until the next chord change. For example, in the following piece of music you’d play a C Major chord in measure 1, an F Major chord in measure 2, a C Major chord in the first half of measure 3, a G7 chord in the second half of measure 3, and a C Major chord in measure 4.

Changing chords in your music.

If you’re writing a part for guitar, or for a rhythm section (bass, piano, and so forth) in a pop or jazz band, you don’t have to write out specific notes on the staff. A guitarist will know to strum the indicated chords, a piano player will know to comp through the chord progressions, and the bass player will know to play the root of the chord.

DEFINITION

Comping is a technique used by jazz and pop musicians to play an improvised accompaniment behind a particular piece of music. A piano player might comp by playing block or arpeggiated chords; a guitarist might comp by strumming the indicated chords.

You write a comp part by using slashes in place of traditional notes on the staff. Typically, you use one slash per beat, so a measure of 4/4 will have four slashes, like this:

Writing chords for a rhythm section.

You can indicate specific rhythms that should be played by writing out the rhythm, but with slashes instead of note heads. The result looks something like this:

Indicating a specific rhythm for the chord accompaniment.

If you’re writing specifically for guitar, you also have the option of including guitar tablature. (A guitar part with tablature is sometimes called guitar tab.) Tablature shows the guitarist how to fret the chord, and is very useful for beginning-level players. More advanced players probably don’t need this assistance, unless you’re indicating a particularly complex chord.

A guitar part with tablature added.

If you go to idiotsguides.com/musictheory, you’ll find a comprehensive reference to just about every kind of chord you can think of—major chords, minor chords, extensions, you name it. You’ll find out how to construct each chord, learn the guitar tablature, and discover alternate ways to describe the chord. Keep this website bookmarked—you’ll get a lot of use out of it!

Exercises

Exercise 9-1

Name the following major chords.

Exercise 9-2

Name the following minor chords.

Exercise 9-3

Write the following major chords on the staff.

Exercise 9-4

Write the following minor chords on the staff.

Name the following extended chords.

Exercise 9-6

Write the following extended chords on the staff.

Exercise 9-7

Write the first and second inversions of the following chords.

Exercise 9-8

Resolve the following suspended chords by lowering the suspended note (the middle note of the chord) to the note a half step below.

- A chord consists of three or more notes (called a triad) played simultaneously—with each note typically a third above the previous note.

- A major chord includes the root note, a major third, and a perfect fifth.

- A minor chord includes the root note, a minor third, and a perfect fifth.

- Extensions above the basic triad are typically added in thirds, and can be either major or minor.

- A minor seventh chord is a minor triad with a minor seventh; a major seventh chord is a major triad with a major seventh; a dominant seventh chord is a major triad with a minor seventh.

- When you play a chord with a note other than the root in the bass, you’re playing a chord inversion.

- When you write for guitar, piano, or bass, you don’t have to write out all the notes; all you have to do is specify the chord, along with rhythmic slashes on the staff.