Chord Progressions

In This Chapter

![]()

- Understanding scale-based chords

- Learning the rules of chord leading

- Figuring out how to end a progression

- Discovering the most common chord progressions

- Fitting chords to a melody—and a melody to a chord progression

In Chapter 9, you learned how to group notes together to form chords. Individual chords alone are interesting, but they become really useful when you string them together to form a succession of chords—what we call a chord progression. These chord progressions provide the harmonic underpinning of a song, “fattening out” the melody and propelling the music forward.

Of course, to create a chord progression that sounds natural, you can’t just string a bunch of chords together willy-nilly. Certain chords naturally lead to other chords; certain chords perform distinct functions within a song. You have to use your chords properly, and arrange them in the right order, to create a piece of music that sounds both natural and logical.

Chord progressions don’t have to be complex, either. The simplest progressions include just two or three chords—which are easy enough for any beginning guitarist to play. How many songs, after all, do you know that use only the G, C, and D chords? (A lot, I bet.) Those three chords comprise one of the most common chord progressions—which should show you how easy all this is.

Chords for Each Note in the Scale

To better understand the theory behind chord progressions, you need to understand that you can create a three-note chord based on any of the seven notes of a major key or scale. You start with the note of the scale (one through seven) as the root of the chord; then build up from there in thirds—using only the notes within the scale.

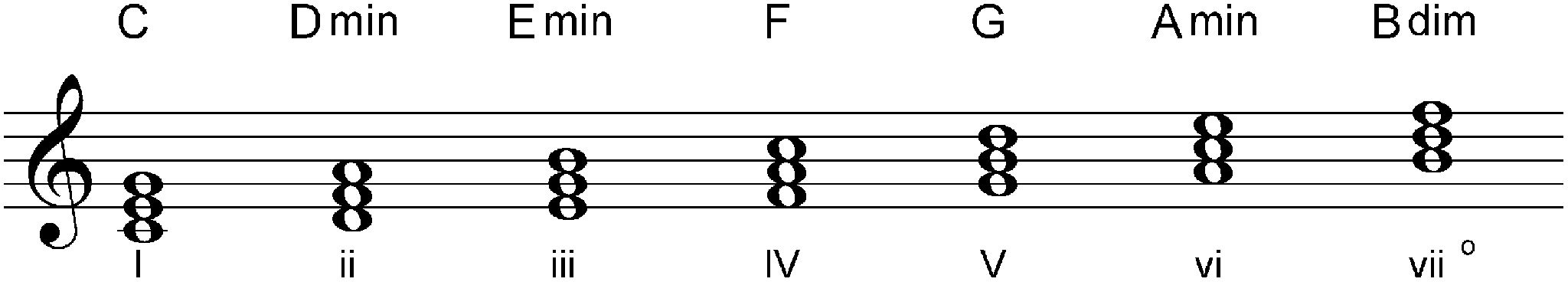

Let’s use the key of C as an example, because it’s made up of only the white keys on a piano. When you play a triad based on C (the tonic of the scale), you play C E G—a C Major chord. Now move up one white key on the keyboard, and play the next triad—D F A, or D minor. Move up another key, and you play E G B, the E minor chord. Move up yet another key, and you play F A C—F Major. Keep moving up the scale and you play G Major, A minor, and B diminished. Then you’re back on C, and ready to start all over again.

This type of chord building based on the notes of a scale is important, because we use the position within a scale to describe the individual chords in our chord progressions. In particular, we use Roman numerals (I through VII) to describe where each chord falls in the underlying scale. Uppercase Roman numerals are used for major chords; lowercase Roman numerals are used for minor chords. To indicate a diminished chord, you use the lowercase Roman numeral plus a small circle (a degree sign: °). To indicate an augmented chord, use the uppercase Roman numeral plus a small plus sign.

Thus, within a major scale, the seven chords are notated as follows:

I ii iii IV V vi vii°

If you remember back to Chapter 2, each degree of the scale has a particular name—tonic, dominant, and so on. We can assign these names to the different chords, like this:

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii° |

Tonic |

Supertonic |

Mediant |

Subdominant |

Dominant |

Submediant |

Leading Tone |

Of these chords, the primary chords—the ones with the most weight—are the I, IV, and V. These also are the only major chords in the major scale—and often the only chords used within a song.

When describing chord progressions, we’ll refer to chords by either their Roman numerals or their theoretical names (tonic, dominant, and so forth). You can figure out which specific chords (C Major, D minor, and so forth) to play, based on the designated key signature.

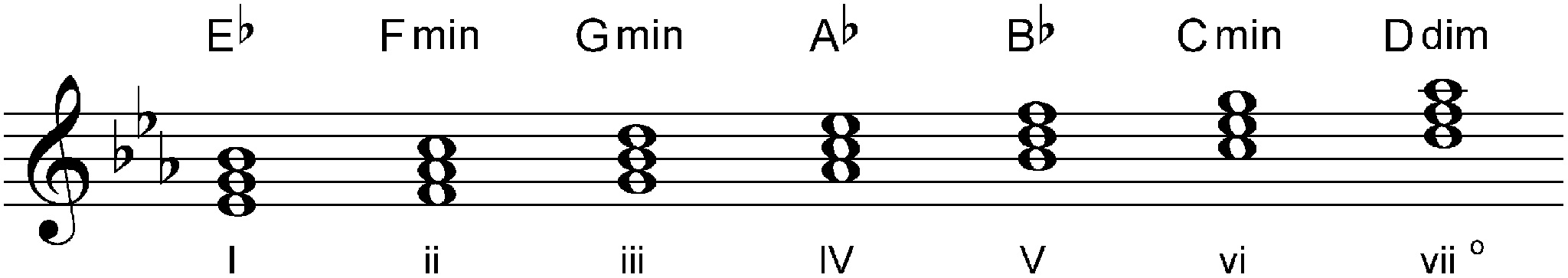

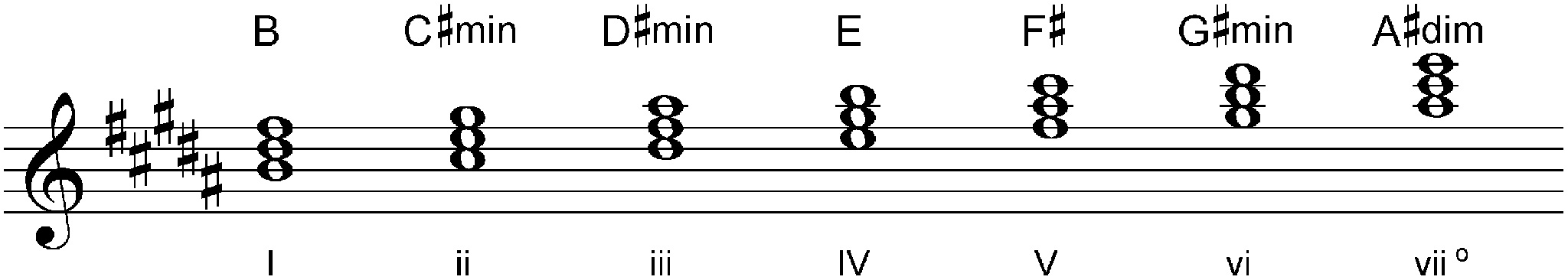

To make things easier, you can refer to the following table, which lists the seven scale-based chords for each major key signature.

Key Signature |

Chords |

| C |  |

| C# |  |

| D♭ |  |

| D |  |

| E♭ |  |

| E |  |

| F |  |

| F# |  |

| G♭ |  |

| G |  |

| A♭ |  |

| A |  |

| B♭ |  |

| B |  |

| C♭ |  |

Let’s see how you can use these Roman numerals to create a chord progression. For the time being we won’t pay attention to the underlying harmonic theory; we’ll just concentrate on the mechanics of creating a progression.

I mentioned earlier the popularity of the G, C, and D chords. In the key of G Major, these chords happen to fall on the first (G), fourth (C), and fifth notes of the scale. This makes these the I, IV, and V chords—or, more technically, the tonic, subdominant, and dominant.

If you’ve ever played any rock, country, or folk songs, you know that one of the more common chord progressions goes like this:

G / / / C / / / G / / / D / / /

(Naturally, the progression repeats—or ends with a final G chord.)

NOTE

These examples use slash notation, where each slash (/) equals one beat. Measures are separated by spaces.

Because you know that the G = I, C = IV, and D = V, it’s easy to figure out the Roman numeral notation. It looks like this:

I IV I V

There—you’ve just written your first chord progression!

The benefit of using this type of notation is you can apply the chord progression to other keys. Let’s say you want to play this I-IV-I-V progression in the key of C. Referring back to the Scale-Based Chords table earlier in this chapter, you can translate the progression to these specific chords:

C / / / F / / / C / / / G / / /

This definitely makes things simpler.

It’s All About Getting Home

The goal of most major chord progressions is to get back to the home chord—the tonic chord, or I. All the other chords in the progression exist as part of a roadmap to deliver you back to the I chord. The route can be simple (just a chord or two) or complex (lots and lots of different chords), but ultimately you want to end up back on I.

As you’ll learn in the next section, certain chords naturally lead to the I chord. In addition, you can employ multiple-chord progressions to get you back to I—these are called cadences and are also discussed later in this chapter.

One Good Chord Leads to Another

Although you can write a song using any combination of chords that sounds good to your ears—even chords from other keys—in most cases chord progressions are based on a few simple rules. These rules come from a concept called chord leading, which says that certain chords naturally lead to other chords.

You can hear chord leading for yourself by playing some chords on the piano. To keep it simple, we’ll stay in the key of C—so you don’t have to play any of the black keys.

Start by playing a C Major chord (C-E-G). This is the I chord, which doesn’t necessarily lead anywhere because, based on chord-leading rules, the I chord can be followed by any chord in the scale.

Now play a G Major chord (G-B-D). This is the V chord in the scale, and it definitely wants to go somewhere. But where? You could follow it with an F Major chord (F-A-C), but that isn’t fully satisfying. Neither is D minor (D-F-A) or E minor (E-G-B) or even A minor (A-C-E). The only chord that sounds fully satisfying—the chord that V naturally leads to—is the I chord, C Major.

The rule here is that the V chord naturally leads back to the I chord. Although you can write another chord after a V, the best resolution is to follow the V with the I.

Other chords also have related chords that they naturally lead to. Some chords can even lead to more than one chord. To learn which chords lead where, take a look at the following table.

Chord Leading Reference

These Chords … |

Lead to These Chords … |

I |

Any chord |

ii |

IV, V, vii° |

iii |

ii, IV, vi |

IV |

I, iii, V, vii° |

V |

I |

vi |

ii, IV, V, I |

vii° |

I, iii |

Although there are exceptions to these rules, you can create a pleasing chord progression by following the order suggested by this chart. This means if you have a iii chord, you follow it with either a ii, IV, or a vi chord. Or if you have a vi chord, you follow it with either a ii, IV, V, or I chord, and so on.

Let’s put together some of these combinations. We’ll start, of course, with the I chord. Because I leads to any chord, let’s go up one scale note and insert the ii chord after the I. According to our chart, ii can lead to either IV, V, or vii°. We’ll pick V. Then, because V always leads to I, the next chord is a return to the tonic.

The entire progression looks like this:

I ii V I

When you play this progression in the key of C, you get the following chords:

C / / / Dm / / / G / / / C / / /

Sounds good, doesn’t it?

Let’s try another example. Again, we’ll start with the tonic, but this time we’ll use the vi chord as the second chord. According to the chart, vi can lead to either ii, IV, V, or I; let’s pick IV. Then, because IV can lead to either I, iii, V, or vii°, we’ll pick V as the next chord—which leads us back to I as our final chord.

The entire progression looks like this:

I vi IV V I

When you play this progression in the key of C, you get the following chords:

C / / / Am / / / F / / / G / / / C / / /

You should recognize that progression as the chords that drove thousands of doo-wop tunes in the 1950s and 1960s.

Let’s return to that progression, and make an alternate choice for the third chord—ii instead of IV. Because ii also leads to V, we can leave the rest of the progression intact, which creates the following alternate progression:

I vi ii V I

This, when played in the key of C, results in these chords:

C / / / Am / / / Dm / / / G / / / C / / /

When you’re playing a chord progression, the number of beats or measures allotted to each chord isn’t set in stone. For example, you could play the I-IV-V progression with a single measure for each chord. Or you could play two measures of I, and a measure each of IV and V. Or you could play three measures of one and then two beats each of IV and V. It all depends on the needs of the song—and helps provide an almost infinite variety of possible chord combinations.

You can also work backward from where you want to end up—your final chord. Because in most cases you want the final chord to be the tonic (I), all you have to do is work through the options that lead to that chord. Consulting the Chord Leading Reference table, you find that four chords can lead to the I: IV, V, vi, and vii°. The obvious choice is the V chord, so that’s what we’ll use. Now we have to pick a chord to lead to V; the choices are ii, IV, vi, and I. Let’s pick ii. Now we pick a chord that leads to the ii; the choices are I, iii, and vi. Let’s pick iii. Now we pick a chord that leads to the iii; the choices are I, IV, and vii°. Let’s pick I, which is also a good chord with which to start our phrase. When you put all these chords together, you get the following progression:

I iii ii V I

Play this progression in the key of C, and you use these chords:

C / / / Em / / / Dm / / / G / / / C / / /

Pretty easy, isn’t it?

Ending a Phrase

When you come to the end of a musical phrase—which can be anywhere in your song, even in the middle of your melody—you use chords to set up a tension, and then relieve that tension. This feeling of a natural ending is called cadence, and there are some accepted chord progressions you can use to provide this feeling of completion.

Perfect Cadence

The most common phrase-ending chord progression uses the V (dominant) chord to set up the tension, which is relieved when you move on to the I (tonic) chord. This progression, called a perfect cadence, is notated V-I. In the key of C, it looks like this:

G / / / C / / /

You could probably see this cadence coming, from the chord leading shown in the table named Chord Leading Reference earlier in this chapter. There’s no better way to get back home (I) than through the dominant chord (V).

TIP

The V-I progression can be enhanced by using the dominant seventh chord (V7) instead of the straight V. This progression is notated V7-I.

Plagal Cadence

A slightly weaker ending progression uses the IV (subdominant) chord in place of the V chord. This IV-I progression is called a plagal cadence; in the key of C, it looks like this:

F / / / C / / /

Although this is an effective cadence, it isn’t nearly as strong as the perfect V-I cadence. For that reason, you might want to use a plagal cadence in the middle of your song or melody, and save the stronger perfect cadence for the big ending.

Imperfect Cadence

Sometimes, especially in the middle of a melody, you might want to end on a chord that isn’t the tonic. In these instances, you’re setting up an unresolved tension, typically by ending on the V (dominant) triad.

This type of ending progression is called an imperfect cadence, and you can get to the V chord any number of ways—I-V, ii-V, IV-V, and vi-V being the most common. In the key of C, these progressions look like this:

I-V: |

C / / / |

G / / / |

ii-V: |

Dm / / / |

G / / / |

IV-V: |

F / / / |

G / / / |

vi-V: |

Am / / / |

G / / / |

Interrupted Cadence

Even less final than an imperfect cadence is an ending progression called an interrupted cadence. In this progression, you use a V chord to trick the listener into thinking a perfect cadence is on its way, but then move to any type of chord except the tonic.

V-IV, V-vi, V-ii, and V-V7 progressions all are interrupted cadences—and, in the key of C, look like this:

V-IV: |

G / / / |

F / / / |

V-vi: |

G / / / |

Am / / / |

V-ii: |

G / / / |

Dm / / / |

V-V7: |

G / / / |

G7 / / / |

NOTE

In classical music theory, an interrupted cadence is more often called a deceptive cadence.

Common Chord Progressions

Given everything you’ve learned about chord leading and cadences, you should be able to create your own musically sound chord progressions. However, just in case you get stuck, let’s take a look at some of the most popular chord progressions used in music today.

I-IV

It doesn’t get much simpler than this, just the tonic (I) and the subdominant (IV) chords repeating back and forth, over and over. This is a cyclical progression, good for songs that don’t really have a final resolution point.

In the key of C, the progression looks like this:

C / / / F / / /

I-V

If you can cycle between the tonic and the subdominant (IV), why not the tonic and the dominant (V)? Like the first progression, the simplicity of this one makes it quite common in folk and some forms of popular music.

In the key of C, the progression looks like this:

C / / / G / / /

Unlike the I-IV progression, this one has a bit more finality, thanks to the V-I relationship. But since you keep going back to the V (and then the I, and then the V again, and then the I again, and on and on), it still is very cyclical sounding.

You can’t get any more popular than the old I-IV-V progression. This is the progression (in the key of G) you’re playing when you strum the chords G, C, and D on your guitar.

There are many different variations on the I-IV-V progression. You can leave out the IV, insert an extra I between the IV and the V, and even tack on another I-V at the end to wrap things up with a perfect cadence. You also can vary the number of beats and measures you devote to each chord.

One example of I-IV-V in a four-measure phrase might look like this, in the key of C:

C / / / C / / / F / / / G / / /

You could also bunch up the IV and the V into a single measure, like this:

C / / / C / / / C / / / F / G /

The progression also could be used over longer phrases, as in this eight-measure example:

C / / / C / / / C / / / C / / /

F / / / F / / / G / / / G / / /

TIP

This progression is often played with a dominant seventh chord on the fifth (V7), which provides increased tension before you return to the tonic.

The point is, these three chords are used in a huge number of modern songs—and make up the core of what many refer to as “three-chord rock and roll.” They’re not limited to rock, of course; many folk, country, jazz, rap, and even classical and show tunes are based on these three chords.

It’s an extremely versatile progression.

I-IV-V-IV

This progression is a variation on I-IV-V. The variation comes in the form of a shift back to the subdominant (IV), which then forms a plagal cadence when it repeats back to the tonic. In the key of C, the progression looks like this:

C / / / F / / / G / / / F / / /

It’s a nice, rolling progression—not too heavy—without a strong ending feeling to it—which makes it nice for tunes that repeat the main melody line again and again.

I-V-vi-IV

This progression is another rolling one, good for repeating again and again. (That’s because of the ending plagal cadence—the IV repeating back to I.)

In the key of C, it looks like this:

C / / / G / / / Am / / / F / / /

I-ii-IV-V

This progression has a constant upward movement, resolved with a perfect cadence on the repeat back to I. In the key of C, it looks like this:

C / / / Dm / / / F / / / G / / /

I-ii-IV

This is a variation on the previous progression, with a soft plagal cadence at the end (the IV going directly to the I, no V involved). In the key of C, it looks like this:

C / / / Dm / / / F / / /

As with all progressions that end with a plagal cadence (IV-I), this progression has a rolling feel, and sounds as if it could go on and on and on, like a giant circle.

I-vi-ii-V

This was a very popular progression in the 1950s, the basis of a lot of doo-wop and jazz songs. It’s also the chord progression behind the song “I’ve Got Rhythm,” and sometimes is referred to (especially in jazz circles) as the “I’ve Got Rhythm” progression.

In the key of C, it looks like this:

C / / / Am / / / Dm / / / G / / /

This is a variation on the “I’ve Got Rhythm” progression, with a stronger lead to the V chord (IV instead of ii). It looks like this, in the key of C:

C / / / Am / / / F / / / G / / /

This progression was also popular in the doo-wop era and in the early days of rock and roll. The defining factor of this progression is the descending bass line; it drops in thirds until it moves up a step for the dominant chord, like this: C-A-F-G. You’ve heard this progression (and that descending bass line) hundreds of times; it’s a very serviceable progression.

I-vi-ii-V7-ii

This is another variation on the “I’ve Got Rhythm” progression, with an extra ii chord squeezed in between the final V and the return to I, and with the V chord played as a dominant seventh. In the key of C, it looks like this:

C / / / Am / / / Dm / / / G7 / Dm /

By adding the ii chord between the V7 and the I, almost in passing, it takes the edge off the perfect cadence and makes the progression a little smoother.

IV-I-IV-V

As this progression shows, you don’t have to start your chord progression on the tonic. In the key of C, it looks like this:

F / / / C / / / F / / / G / / /

This progression has a bit of a rolling nature to it, but also a bit of an unresolved nature. You can keep repeating this progression (leading from the V back to the IV), or end the song by leading the progression home to a I chord.

NOTE

The IV-I-IV-V progression is also frequently played at the end of a phrase in many jazz tunes. Used in this manner, it’s called a turnaround. (See Chapter 16 to learn more.)

This progression is quite popular in jazz, often played with seventh chords throughout. So you might actually play a ii7-V7-I progression, like this (in the key of C):

Dm7 / / / G7 / / / CM7 / / /

Sometimes jazz tunes cycle through this progression in a variety of keys, often using the circle of fifths to modulate through the keys. (That’s the term you use any time you change the key within a song.)

Circle of Fifths Progression

There’s one more chord progression that’s fairly common, and it’s based on the circle of fifths you learned about back in Chapter 4. Put simply, it’s a progression where each chord is a fifth above the next chord; each chord functions as the dominant chord for the succeeding chord. The progression circles back around on itself, always coming back to the tonic chord, like this: I-IV-vii°-iii-vi-ii-V-I.

Here’s what the progression looks like in the key of C:

C / / / F / / / Bdim / / / Em / / / Am / / / D / / / G / / / C / / /

You can also play this progression backward, creating a circle of fourths, but that isn’t nearly as common as the one detailed here.

Chromatic Circle of Fifths

The circle of fifths progression we just discussed is a simple one you can use without getting into nonscale chords. But there’s also another, longer, circle of fifths progression, based on chromatic chords, that you might want to play around with.

This progression is a little too complex to write out in Roman numeral notation, but it works by having each chord function as the precise subdominant of the next chord—that is, the chords move in perfect fifths around the chromatic scale. Even more fun, each chord is turned into a dominant seventh chord, to make the dominant-tonic relationship more explicit.

Here’s how it looks, in the key of C:

C / / / |

C7 / / / |

F / / / |

F7 / / / |

Bb / / / |

Bb7 / / / |

|

Eb / / / |

Eb7 / / / |

Ab/ / / |

Ab7 / / / |

Db / / / |

Db7 / / / |

|

Gb / / / |

Gb7 / / / |

B / / / |

B7 / / / |

E / / / |

E7 / / / |

|

A / / / |

A7 / / / |

D / / / |

D7 / / / |

G / / / |

G7 / / / |

C |

You can jump on and off this progression at any point in the cycle. Kind of neat how it circles around, isn’t it?

Singing the Blues

There’s a unique chord progression associated with the genre of music we commonly call the blues. This blues form isn’t relegated solely to blues music, however; you’ll find this form used in many jazz and popular tunes, as well.

The blues progression is a 12-measure progression. (It’s sometimes called a “12-bar blues.”) This 12-measure progression repeats again and again throughout the melody and any instrumental solos.

The form is essentially a I-IV-I-V7-I progression, but spread over 12 measures, like this:

I / / / |

I / / / |

I / / / |

I / / / |

IV / / / |

IV / / / |

I / / / |

I / / / |

V7 / / / |

V7 / / / |

I / / / |

I / / / |

In the key of C, the blues progression looks like this:

C / / / |

C / / / |

C / / / |

C / / / |

F / / / |

F / / / |

C / / / |

C / / / |

G7 / / / |

G7 / / / |

C / / / |

C / / / |

Although these are the basic blues chords, you can use lots of variations to spice up individual songs. (Turn to Chapter 16 to see some of these variations.)

NOTE

The blues progression is sometimes played with a V7 chord in the final measure.

Chords and Melodies

Although chords fill out a tune and provide its harmonic underpinning, you still need a melody to make a song.

The relationship between chords and melody is complex—and works a little like the proverbial chicken and the egg. You can start with one or the other, but in the end you have to have both.

This means you can write a melody to a given chord progression, or you can start with the melody and harmonize it with the appropriate chords. There’s no set place to start; whether you start with the melody or the chords is entirely up to you.

Fitting Chords to a Melody

If you write your melody first, you then have to figure out which chords fit where. In many cases, it’s a simple matter of applying one of the common chord progressions to your melody; more often than not, you’ll find one that’s a perfect fit.

To demonstrate, let’s look at the chords behind some of the melodies we first examined back in Chapter 8.

“Michael, Row the Boat Ashore”

We’ll start with “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore,” which is a great example of a progression that relies heavily on the I, IV, and V chords—but with a few twists. Here’s the song, complete with chords:

The chords to “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore.”

The first twist in the chord progression comes in the fifth full measure (the start of the second phrase), which uses the iii chord (F#m) instead of the expected I. The second twist is the sixth measure, which moves down to the ii chord (Em). From there the melody ends with a perfect cadence (I-V-I), just as you’d expect.

So, if you started your hunt for the perfect progression for this melody by applying a standard I-IV-V progression, you’d be in the right neighborhood.

Bach’s Minuet in G

Next, let’s examine Bach’s Minuet in G. Again, if you apply the standard I-IV-V progression, you’ll be pretty much on the mark, as you can see here:

The chords to Bach’s Minuet in G.

Old Johann was able to wring the most out of a very simple chord progression; in this case nothing more than I-IV-I-IV-I-V-I. Of course, this shows that you don’t need a complex chord progression to create great music.

Dvořák’s New World Symphony

Dvořák’s New World Symphony uses another relatively simple chord progression, as you can see here:

The chords to Dvořák’s New World Symphony.

The chord progression is basically I-V-I, with a neat little ii-V-I imperfect-to-perfect cadence at the end. There’s also a unique non-scale twist in the second half of the third measure, where the I chord (D♭) suddenly gets a raised fifth and goes augmented. (In the orchestral score, the fifth is in the bass in this measure, for a very dramatic effect.) The use of the augmented tonic sets up an unexpected tension, without messing up the harmonic structure by throwing in something like a IV or a V chord where it wouldn’t really belong.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D

Even more simple is the chord progression behind Pachelbel’s Canon in D, as you can see here:

The chords to Pachelbel’s Canon in D.

Note how the chords flow, one into the next, based more or less on established chord leading rules—I-V-vi-iii-IV-I-IV-V—and then back to the I, again and again. You can play this progression all night long and not get tired of it; that’s what makes it such a classic.

“Mary Had a Little Lamb”

Finally, let’s figure out the chords to “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Just as the melody is a simple one, so is the accompanying chord progression—nothing more than I-V-I, repeated once. Sometimes the simplest progressions are the best!

The chords to “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

Chord Writing Tips

When it comes to fitting a chord progression to an existing melody, here are some tips to keep in mind:

- Try some common chord changes first. You’d be surprised how many melodies fit with the I-IV-V progression!

- The main notes in the melody (typically the notes that fall on the first and third beats of a measure) are the first, third, or fifth note of the underlying chord.

- Try to simplify the melody by cutting out the passing and neighboring tones (typically the shorter notes, or the notes not on major beats); the main notes you have left often will suggest the underlying chord.

- Make sure you’re in the right key. In most cases, the “home” note in the melody is the tonic note of the underlying key.

NOTE

Jazz musicians sometimes refer to chord progressions as chord changes—as in, “Dig those crazy changes, man!”

- Generally, the slower the tempo, the more frequent the chord changes. (So if you have a long whole note, or a note held over several measures, expect to find several different chords played behind that single note.)

- Work backward from the end of a melodic phrase, remembering that melodies almost always end on the I chord. You then can figure out the cadence leading to the I, and have half the song decoded fairly quickly.

- Chord changes typically fit within the measure structure, which means you’re likely to see new chords introduced on either the first or third beat of a measure.

Writing a Melody to a Chord Progression

You don’t have to start with a melody; you can base your tune on a specific chord progression and compose a melody that best fits the chords.

If you prefer to work this way, it helps to get a good feel for the chord progression before you start writing the melody. Play the chords again and again on either a piano or guitar. In many cases, you’ll find a melody forming in your head; if this type of natural melody comes to you, you only have to figure out the notes and write them down.

If no natural melody occurs, it’s time to roll out the theory. You don’t want to work totally mechanically, but there are some basic approaches you can use. Take a look at these tips:

- Stay within the notes of the chords—at least for the main notes in the melody. If you’re holding an A minor chord in a specific measure, work with the notes A, C, and E for your melody.

A simple melody for the popular I-IV-V chord progression—note the heavy use of chord notes in the melody. The notes indicated with a (p) are passing tones.

NOTE

In this example, the C in measure 3, beat 4 is technically an anticipation, not a passing tone. An anticipation is, in effect, an “eager” note—a note from the next chord that is sounded just a little earlier than the chord itself.

- Try to find a logical line between the main notes in different measures. For example, if your chord progression goes C-Am-F, realize that these chords have one note in common—the C. So you can base your melody around the C note. Conversely, if your chord progression goes C-F-G, you might want to pick three notes (one from each chord) that flow smoothly together—E to F to G, for example; or G to F to D.

- Use notes that emphasize the quality of the underlying chords. For example, when you’re writing to a V7 chord, emphasize the tension by using either the root or the seventh of the chord in the melody.

- Once you pick your main tones, fill in the gaps with passing tones.

- Come up with an interesting rhythmic motif, and repeat that rhythm throughout the melody.

I wish there were a more complete set of rules for adding a melody to a chord progression, but we’re getting into an area that is more art than science. As it should be! The best way to hone your skill is simply to work at it—play a lot of chord progressions, and practice writing different types of melodies over the chords. (And remember to read my companion book, The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Music Composition, for lots more advice and instruction.)

Over time, you’ll figure out your own rules for writing melodies—and develop your own melodic style.

Exercises

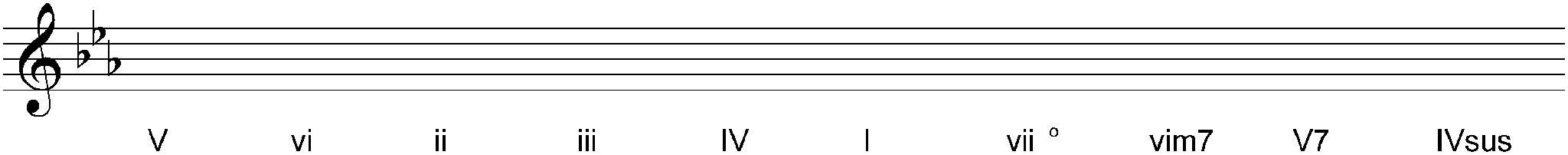

Exercise 10-1

Write the following chords in the key of F.

Exercise 10-2

Write the following chords in the key of D.

Write the following chords in the key of E♭.

Exercise 10-4

Write the chords that lead from the following chords, in the key of C.

Exercise 10-5

Create the following types of cadences in the key of A.

Exercise 10-6

Figure out which chords go with the following melody. (Hint: there are two chords in every measure.)

Exercise 10-7

Write a melody to the following eight-measure chord progression.

- Every note of the scale has an associated chord, notated by a Roman numeral (uppercase for major; lowercase for minor).

- Chord progressions naturally lead back to the tonic, or I, chord of the underlying scale.

- Every chord naturally leads to at least one other chord; for example, the V chord naturally leads to the I.

- The final chords in a progression—the ones that ultimately lead back to I—are called a cadence.

- The most common chord progressions include I-IV, I-V, I-IV-V, I-IV-V-IV, I-V-vi-IV, I-ii-IV-V, I-ii-IV, I-vi-ii-V, I-vi-IV-V, I-vi-ii-V7-ii, IV-I-IV-V, and ii-V-I.