Special Notation

In This Chapter

![]()

- Discovering how to notate phrasing with slur marks

- Writing and playing embellished notes, including turns, trills, and grace notes

- Learning how to play music with a swing feel

- Fitting words to music

Some aspects of music theory just don’t fit neatly within traditional categories. Still, you need to know about them, so I have to include them somewhere in this book.

That somewhere is this chapter. It’s kind of a grab bag of more advanced techniques, mainly relating to notation, that you need to have at your fingertips—even if you won’t use them every day.

So settle back and read about some of the oddball aspects of music theory, and that popular musical style we call swing.

When you’re writing music, you sometimes need to connect two or more notes together. You might literally connect them together to form a single, longer note, or you might simply want them played together as a smooth phrase. In any case, whenever you connect two or more notes together, you use a notation effect that looks like a big curve—and is called, alternately, either a tie or a slur.

Ties

You learned about ties back in Chapter 5. When two notes of the same pitch are tied together—either in the same measure, or across measures—the notes are played as a single note.

A tie is made with a small curve, either above or below the note, like this:

Two identical notes tied together equal one long note.

Slurs

A slur looks like a tie between two notes of different pitches, but really indicates that the notes are to be played together as a continuous group. Although you can’t play two different tones as a continuous note, you can run them together without a breath or a space in between. This is called “slurring” the notes together; it looks like this:

Two different notes tied together are slurred together.

NOTE

The curved line used in a slur is called a slur mark.

There’s a subtle difference between two notes that are slurred together and two notes that aren’t. The notes without the slur should each have a separate attack, which ends up sounding like a slight emphasis on each note. The second of the two slurred notes doesn’t have a separate attack, so the sound is much smoother as you play from note to note.

When you see a curved line above several adjacent notes, it’s not a slur—it’s a phrase. You use phrase marks to indicate separate ideas within a longer piece of music. When one idea ends, you end the phrase mark; when a new idea begins, you start a new phrase mark.

Lots of notes grouped together are played as a smooth phrase.

NOTE

Technically, a phrase mark indicates that a passage of music is played legato—which means to play smoothly.

Often, wind instruments (trumpets, clarinets, and so forth) base their breathing on the song’s phrases. They’ll blow during the phrase and breathe between the phrase marks.

Bowed instruments (violins, cellos, and so forth) use phrases to time their bowing. They’ll use a single, continuous movement of the bow for the duration of the phrase; at the end of the phrase mark, they’ll change the direction of their bowing.

The Long and the Short of It

Back in Chapter 7, you learned about some of the embellishments you can make to individual notes—accents, marcatos, and so on. There are a few more marks you can add to your notes; they’re presented here.

Tenuto

A straight horizontal line over a note means to play the note for its full duration. In other words, stretch it out for as long as possible.

This mark is called a tenuto mark, and it looks like this:

The tenuto mark means to play a long note.

The opposite of a long note is a short note; the opposite of tenuto is staccato. A dot on top of a note means to not play it for its full duration; just give it a little blip and get off it.

A staccato mark looks like this:

The staccato mark means to play a short note.

When Is a Note More Than a Note?

There are other marks you can add to your notes that indicate additional notes to play. These notes are kind of musical shorthand you can use in place of writing out all those piddly smaller notes.

Grace Notes

A grace note is a short note you play in front of a main note. In mathematical terms, a grace note might have the value of a sixteenth or a thirty-second note, depending on the tempo of the music. Basically, you play the grace note just ahead of the main note, at a slightly lower volume level. When you note a grace note, write it as a smaller note just in front of the main note, like this:

A grace note is like a little preview note before the main note.

Grace notes are typically written as small eighth notes, with a line drawn through the stem and flag. The grace note can be on the same tone as the main note, or on an adjoining tone. (You play whatever note the grace note is on.)

NOTE

Drummers call a grace note a flam, because (on a drum) that’s what it sounds like—“fa-lam!”

A turn is an ornament used primarily in Baroque and classical music. In a turn, the neighboring notes turn to the main note, “turning it around.”

Let’s look at how a turn works: when you see the turn mark (which looks like a line turned around on itself), you play the diatonic note above the main note, then the main note, then the note a step below the main note, and then the main note again. Here’s how it looks on paper, and how you play it in practice:

A turn “turns around” the main note.

When you’re playing a turn, you have a bit of latitude for how fast you actually play it. You can play a turn as written in the example, as a pure mathematical subset of the note’s noted duration; or you can whip through the turn really quickly, landing back on the main pitch until the note is done. It’s all a matter of interpretation.

TIP

If you’re unsure how to play a turn in a piece of music, ask your conductor for the proper interpretation.

Trills

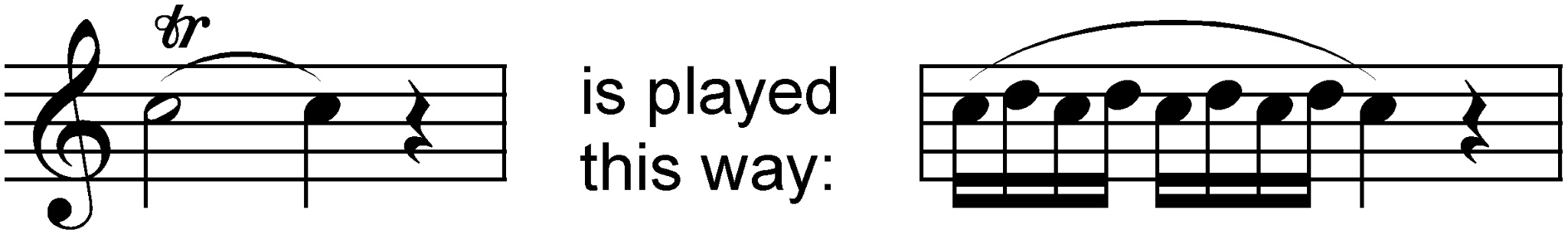

A trill (s) is a way to extend a single note by alternating between two neighboring tones. In particular, you alternate between the main note and the note one step above, like this:

Play a trill with a whole bunch of neighboring notes.

As with turns, there are many different ways to play a trill. The most common approach is to alternate between the two notes as rapidly as possible, although technically a trill can have a preparation in which you play the main note straight before you enter into the “shake.” (You can also terminate the trill—or just trill right into the next note.)

Whereas turns and trills alternate between two or three neighboring notes, a glissando packs a lot more notes into a short space. To be precise, a glissando is a mechanism for getting from one pitch to another, playing every single pitch between the two notes as smoothly as possible.

NOTE

On the piano, you can also “cheat” a glissando by playing only the white keys between the top and bottom tones—which lets you play a glissando with a stroke of your hand.

Depending on the instrument, a glissando can be a continuous glide between the two notes (think trombone) or a run of sequential chromatic notes (think piano). Glissandi (not glissandos!) can move either up or down; typically, both the starting and ending notes are specified, like this:

Glissando up—and down.

Arpeggiated Chords

When you want an instrument to play a chord as an arpeggio, but you don’t want to write out all the notes, you can use the symbol called the role. The role indicates that the instrument is to play an arpeggio—but a rather quick one. This squiggly line tells the musician to play the written notes from bottom to top, in succession, and to hold each note as it is played. The effect should be something like a harp playing an arpeggiated chord, like this:

The quick and easy way to notate an arpeggiated accompaniment.

Getting Into the Swing of Things

The last bit of notation I want to discuss concerns a feel. If you’ve ever heard jazz music, particularly big band music, you’ve heard this feel; it’s called swing.

Traditional popular music has a straight feel; eighth notes are played straight, just as they’re written. Swing has a kind of triplet feel; it swings along, all bouncy, percolating with three eighth notes on every beat.

What’s that, you’re saying—three eighth notes on every beat? How is that possible?

It’s possible because swing is based on triplets. Instead of having eight eighth notes in a measure of 4/4, you have twelve eighth notes—four eighth-note triplets. So instead of the basic beat being straight eighths, the first and third beat of every triplet combine for a spang-a-lang-a-lang-a-lang kind of rhythm.

What’s confusing is that instead of notating swing as it’s actually played (with triplets), most swing music uses straight eighth notation—which you’re then expected to translate into the triplet-based swing.

So if you’re presented a swing tune and you see a bunch of straight eighths, you should play them with a triplet feel instead, like this:

In swing, straight eighths are played with a triplet feel.

Some arrangers try to approximate the swing feel within a straight rhythm by using dotted eighth notes followed by sixteenth notes, like this:

In swing, dotted eights and sixteenths are played with a triplet feel.

Whatever you do, don’t play this precisely as written! Again, you have to translate the notation and play the notes with a triplet feel.

The swing feel is an important one, and you find it all over the place. Swing is used extensively in jazz music, in traditional blues music, in rock shuffles, and in all manner of popular music old and new. Learning how to swing takes a bit of effort; it’s normal to play the stiff dotted-eighth/sixteenth rhythm instead of the rolling triplets when you’re first starting out. But that effort is worth it—a lot of great music is based on that swinging feel.

Getting the Word

Before we end this chapter, let’s take a look at one other notation challenge: how to add words to your music.

Notating lyrics is something that all songwriters have to do, and it isn’t that hard—if you think logically. Naturally, you want to align specific words with specific notes in the music. More precisely, you want to align specific syllables with specific notes.

This sometimes requires a bit of creativity on your part. You might need to split up words into awkward-looking syllables. You also might need to extend syllables within words where a note is held for an extended period of time. This requires a lot of hyphens in the lyrics, as you can see in the following example:

Notating lyrics; split words in syllables, and extended syllables.

Just remember to position your lyrics underneath the music staff. If you have multiple verses, write each verse on a separate line; then break each word into its component syllables and carefully match up each syllable with the proper musical note.

Exercises

Exercise 17-1

Write out how you would play each of these marked-up notes.

Exercise 17-2

Add grace notes to every quarter note in this melody.

Exercise 17-3

Add slurs to each pair of eighth notes in this melody.

Use phrase marks to divide this melody into four natural phrases.

Exercise 17-5

Translate the following straight rhythm into a swing feel using triplet notation.

Exercise 17-6

Compose and play a four-measure melody with a swing feel, in the key of B♭.

Exercise 17-7

Write the following lyrics under the appropriate notes in the melody: “Tangerine elephants high in the sky, crocodile tears in my beer.”

- Curved marks are used to tie identical notes together, slur neighboring notes together, and indicate complete musical phrases.

- A dot above a note means to play it short (staccato); a line above a note means to play it long (tenuto).

- You play grace notes lightly and quickly before the main note.

- Turns and trills ornament a main note by the use of rapidly played neighboring notes.

- A glissando indicates a smooth glide from one pitch to another.

- Swing music is played with a rolling triplet feel, not straight eighth notes.

- Lyrics must be broken down into syllables to fit precisely with notes in the music.