Chord Substitutions and Turnarounds

In This Chapter

![]()

- Learning to spice up boring chord progressions with extensions

- Discovering how to alter a chord’s bass note and play two chords simultaneously

- Mastering the art of chord substitution

This section of the book is all about embellishing your music. You can embellish your melody with harmony and counterpoint (as you learned in the previous chapter), embellish individual notes (as you’ll learn in the next chapter), and embellish your chords and chord progressions. That’s what this chapter is all about.

Even if you’re stuck with a boring I-IV-V progression, there is still a lot you can do to put your own personal stamp on things. For example, you don’t have to settle for precisely those chords; you can extend the chords, alter the bass line, and even substitute other chords for the originals. You’ll still maintain the song’s original harmonic structure—more or less—but you’ll really jazz up the way things sound.

All this will impress your listeners and fellow musicians. A few key chord alterations and substitutions will make folks think you have the right touch—and that you really know your music theory!

The simplest way to spice up a boring chord progression is to use seventh chords, or even add a few extensions beyond that. As you learned back in Chapter 9, the basic chord is a triad consisting of the 1-3-5 notes. When you start adding notes on top of the triad—sevenths, ninths, and elevenths—you’re extending the chord upward.

Chord extensions can make a basic chord sound lush and exotic. There’s nothing like a minor seventh or major ninth chord to create a really full, harmonically complex sound.

Seventh chords—especially dominant seventh chords—are common in all types of music today. Sixths, ninths, and other extended chords are used frequently in modern jazz music—and in movie and television soundtracks that go for a jazzy feel. Pick up just about any jazz record from the 1950s on, and you’ll hear lots of extended chords. There are even a lot of rock and pop musicians—Steely Dan comes to mind—who embrace these jazz harmonies in their music. So why not use this technique yourself?

NOTE

Seventh chords have been part of the musical vocabulary from about the seventeenth century. There is a tendency to use the V7 and ii7 chords as much as or more than the triads on those degrees of the scale—even for the simplest musical genres, such as hymns and folk songs. In the blues, it is common to use seventh chords on every scale degree—even the tonic. Other extended chords (ninths, elevenths, and so forth) came into widespread use in the nineteenth century, and are still used in many forms of music today. For example, in many jazz compositions the ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords are used more often than triads and seventh chords.

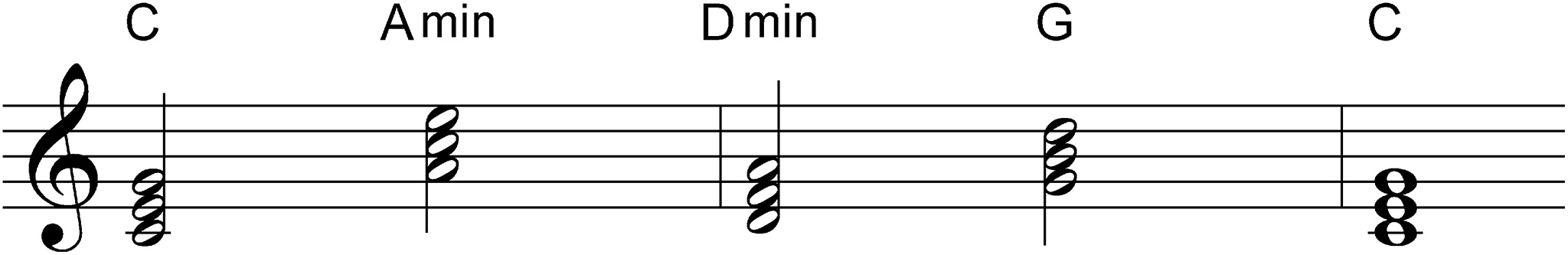

Here’s an example of how extended chords can make a simple chord progression sound more harmonically complex. All you have to do is take the standard I-vi-IV-V progression in the key of C (C-Am-F-G) and add diatonic sevenths to each triad. That produces the following progression: CM7-Am7-FM7-G7—two major sevenths, a minor seventh, and a dominant seventh. When you play this progression—and invert some of the chords to create a few close voicings—you get a completely different sound out of that old workhorse progression. And it wasn’t hard to do at all!

The standard I-vi-IV-V progression (in C) embellished with seventh chords (and some close voicings).

You can get the same effect by adding ninths and elevenths to your chords while staying within the song’s underlying key. The more notes you add to your chords, the more complex your harmonies—and the fuller the sound.

Altering the Bass

Here’s another neat way to make old chords sound new—and all you have to do is change the note on the bottom of the chord.

Back in Chapter 9 we touched briefly on the concept of slash chords, more properly called altered bass chords. With an altered bass chord, the top of the chord stays the same, but the bass, as the name implies, is altered.

Some folks call these chords slash chords because the altered bass note is indicated after a diagonal slash mark, like this: G/D. You read the chord as “G over D,” and you play it as a G chord with a D in the bass.

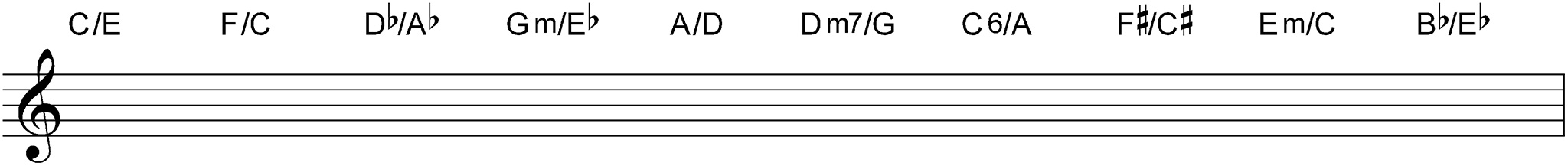

Examples of slash chords.

You can use altered bass chords to achieve several different effects, including the following:

- By putting one of the three main notes (but not the root) in the bass, you dictate a particular chord inversion.

- By treating the bass note as a separate entity, you can create moving bass lines with increased melodic interest.

- By adding a nonchord note in the bass, you create a different chord with a different harmonic structure.

Slash chords are used a lot in jazz, and also in more sophisticated popular music. Listen to Carole King’s Tapestry album, and you’ll hear a lot of altered bass (she’s a big fan of the minor seventh chord with the fourth in the bass); the same thing with a lot of Beach Boys songs, especially those on the legendary Pet Sounds album.

Two Chords Are Better Than One

An altered bass chord uses a diagonal slash mark to separate the chord from the bass note. When you see a chord with a horizontal line between two different chord symbols, like a fraction, you’re dealing with a much different beast.

This type of notation indicates that two chords are to be played simultaneously. The chord on top of the fraction is placed on top of the pile; the chord on the bottom is played underneath. For example, when you see ![]() you know to play a C Major chord on top of a full G Major chord.

you know to play a C Major chord on top of a full G Major chord.

Examples of compound chords.

When you play two chords together like this, you have what’s called a compound chord. You use compound chords to create extremely complex harmonies—those that might otherwise be too complex to note using traditional extensions.

One Good Chord Can Replace Another

When you’re faced with a boring chord progression, you may have no alternative but to substitute the chords as written with something a little less boring. The concept of chord substitution is common in jazz (those jazz musicians get bored easily!) and other modern music.

Chord substitution is a simple concept. You pull a chord out of the song, and replace it with another chord. The substitute chord should have a few things in common with the chord it replaces, not the least of which is its place in the song’s underlying harmonic structure. So if you replace a dominant (V) chord, you want to use a chord that also leads back to the tonic (I). If you replace a major chord, you want to replace it with another major chord or a chord that uses some of the same notes as the original chord.

The key thing is to substitute an ordinary chord or progression with one that serves the same function, but in a more interesting manner.

Diatonic Substitution

The easiest form of chord substitution replaces a chord with a related chord either a third above or a third below the original. This way you keep two of the three notes of the original chord, which provides a strong harmonic basis for the new chord.

This type of substitution is called diatonic substitution, because you’re not altering any of the notes of the underlying scale; you’re just using different notes from within the scale for the new chord.

For example, the I chord in any scale can be replaced by the vi chord (the chord a third below) or the iii chord (the chord a third above). In the key of C, this means replacing the C Major chord (C-E-G) with either A minor (A-C-E) or E minor (E-G-B). Both chords share two notes in common with the C chord, so the replacement isn’t too jarring.

Replacing the I chord (C Major) with the vi (A minor) and the iii (E minor)—lots of notes in common.

You can replace extended chords in the same manner, and actually end up with more notes in common. For example, you can replace CM7 with either Am7 or Em7, both of which have three notes in common with the original chord.

Major Chord Substitutions

Diatonic substitution is the theory; you’d probably rather know some hard-and-fast rules you can use for real-world chord substitution. Don’t worry; they exist, based partially on diatonic substitution theory.

The following table presents three different substitutions you can make for a standard major chord. Remember that the root of the substitute chord must stay within the underlying scale, even if some of the chord notes occasionally wander about a bit.

Major Chord Substitutions

Substitution |

Example (for the C Major Chord) |

Minor chord a third below |

|

Minor 7 chord a third below |

|

Minor chord a third above |

|

The first substitution in the table is the standard “down a third” diatonic substitution. The second substitution is the same thing, but uses an extended chord (the minor seventh) for the substitution. The third substitution is the “up a third” diatonic substitution, as discussed previously.

Minor Chord Substitutions

Substituting a major chord is relatively easy. So what about substituting a minor chord?

As you can see in the following table, some of the same substitution rules work with minor as well as major, especially the “up a third” and “down a third” diatonic substitutions.

Minor Chord Substitutions

Substitution |

Example (for the A Minor Chord) |

Major chord a third above |

|

Major chord a third below |

|

Major 7 chord a third below |

|

Diminished chord with same root |

|

The last substitution falls into the “more of a good thing” category. That is, if a minor chord sounds good, let’s flat another note and it’ll sound even more minor. Some folks like the use of a diminished chord in this fashion; others don’t. Let your ears be the judge.

Dominant Seventh Substitutions

Okay, now you know how to substitute both major and minor chords, but what about dominant seventh chords? They’re not really major, and they’re not really minor—what kind of chords can substitute for that?

The answer requires some harmonic creativity. You can do a diatonic substitution (using the diminished chords a third above or below the dominant seventh), but there are more interesting possibilities, as you can see in the following table.

Dominant Seventh Chord Substitutions

Substitution |

Example (for the G7 Chord) |

Major chord a second below |

|

Minor 7 chord a third below |

|

Diminished chord a third above |

|

Minor 7 chord a fourth below—over the same root |

|

The more interesting substitutions here are the first one and the last one. The first substitution replaces the V7 chord with a IV chord; the use of the sub-dominant (IV) chord results in a softer lead back to the I chord. The last substitution uses an altered chord, so that you’re leading back to tonic with a iim7/V—what I like to call a “Carole King chord.” (That’s because Ms. King uses this type of harmonic structure a lot in her songwriting.) So if you’re in the key of C, instead of ending a phrase with a G or G7 chord, you end with a Dm7/G instead. It’s a very pleasing sound.

Functional Substitutions

Here’s something else to keep in mind. Within the harmonic context of a composition, different chords serve different functions. The three basic harmonic functions are those of the tonic, subdominant, and dominant—typically served by the I, IV, and V chords, respectively. But other chords in the scale can serve these same functions, even if not as strongly as the I, IV, and V.

For example, the subdominant function can be served by either the ii, IV, or vi chords. The dominant function can be served by either the V or vii° chords. And the tonic function can be served by either the I, iii, or vi chords. All these functions are shown in the following table.

NOTE

Just in case you think you found a mistake in the preceding table, the vi chord can serve both the tonic and subdominant functions. It’s a very versatile chord!

When you have a chord serving a specific function in a composition, you can replace it with another chord of the same type. So if you have a IV chord, serving a subdominant function, you can substitute any of the other subdominant-functioning chords—the ii or the vi. Along the same lines, if you have a ii chord, you can replace it with either the IV or the vi.

The same thing goes with the other functions. If you have a V chord, serving a dominant function, you can replace it with a vii° chord—or vice versa. And a I chord, serving a tonic function, can be replaced by either a iii or a vi chord—and also vice versa. It’s actually a fairly easy way to make some simple chord substitutions.

Turnarounds

Chapter 10 also presented a concept of the phrase-ending cadence. Well, in the fields of jazz and popular music, you find a similar concept called a turnaround. A turnaround typically is a two-bar phrase, with two chords per measure, that functions much the same as a traditional cadence, “turning around” the music to settle back on the I chord at the start of the next phrase.

NOTE

Some jazz musicians refer to turnarounds as turnbacks.

There is a wide variety of chord combinations you can use to create an ear-pleasing turnaround, some of which go outside the underlying key to circle back around to the tonic.

The following table offers a few you might want to try.

Turnaround |

Example (in C) |

I-IV-iii-ii |

|

I-vi-ii-V |

|

iii-VI-ii-V |

|

I-vi-♭vi-V |

|

I-♭VII-iii-ii |

|

IV-iii-ii-♭ii |

|

I-vi-♭vi-♭II |

|

I-VI-♭V-♭III |

|

I-♭III-♭VI-♭II |

|

I-♭VII-♭III-♭II |

|

Note that some of these outside-the-key chords take traditionally minor chords and make them major, so pay close attention to the uppercase and lowercase notation in the table. (For example, the III chord is an E Major chord in the key of C, not the expected E minor.)

Also pay attention to flat signs before a chord; this indicates to play the chord a half step lower than normal. For example, a ♭vi chord in the key of C is a half step lower than the standard A minor vi chord, which results in the A♭ minor chord instead.

You can use these turnarounds in any of the songs you write or arrange. It’s an easy way to add harmonic sophistication to your music, just by changing a few chords at the end of a phrase!

Exercises

Exercise 16-1

Write out the notes for the following slash chords.

Exercise 16-2

Write out the notes for the following compound chords.

Exercise 16-3

Write two substitute chords for each chord shown.

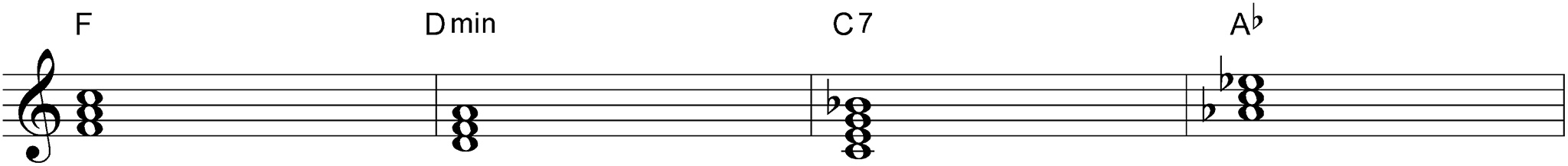

Rewrite the following chord progression (on the second staff), using extended chords.

Exercise 16-5

Rewrite the following chord progression (on the second staff), using various types of chord substitutions.

Exercise 16-6

Add a two-measure turnaround to the following chord progression.

- When you don’t want to play a boring old chord progression, you can use one of several techniques to make the chord progression sound more harmonically sophisticated.

- The easiest way to spice up a chord progression is to change triads to seventh chords or extended chords (such as sixths, ninths, elevenths, or thirteenths), and add sevenths and other extensions to the basic chords.

- Another way to change the sound of a chord is to alter the bass note—to either signal a different inversion, or to introduce a slightly different harmonic structure.

- Substituting one chord for another also can make a chord progression more interesting. The most common chord substitutions are diatonic, in which you replace a chord with the diatonic chord either a third above or below the original chord.

- You can also perform a chord substitution based on chord function. Any chord fulfilling a tonic, subdominant, or dominant function can be replaced by any other chord fulfilling the same function.

- You can add interest to a chord progression by introducing a two-measure turnaround at the end of the main phrase; these chords circle around and lead back to the I chord at the start of the next phrase.