4. Monitoring, Regulating, and Disciplining Employees Using Social Media

Given the high potential for damage to an employer’s business that can arise from an employee’s irresponsible use of social media, employers are increasingly monitoring and disciplining workers over such misuse. As detailed below, such activities, although primarily motivated by sound business-related reasons, are nonetheless subject to legal scrutiny, putting employers at risk of monetary fines, reinstatement of terminated employees, payment of lost wages, and other damages.

Social media has been aptly described as a double-edged sword for employers. Despite the obvious work-related benefits, employee use of social media is not without considerable risk.

Employee Monitoring

Monitoring employee use of social media makes sound business sense, but companies need to keep limits in mind, particularly as they relate to employee’s privacy rights under both federal and state law. For instance, accessing password-restricted sites handled by employees can violate many federal and state privacy laws, including the Stored Communications Act (SCA),1 which makes it an offense to intentionally access stored communications without authorization or in excess of authorization.2 Note, however, that the statute also provides an exception to liability with respect to conduct authorized by a user with regard to a communication intended for that user—for example, an employee affirmatively authorizes her employer to access her email account or Facebook page.3

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

An employer’s use of its employees’ personal social media accounts—even accounts which are partially used for business purposes—carries significant risk. In Maremont v. Susan Fredman Design Group,4 for example, the employer, an interior design firm headquartered in Chicago, allegedly accessed its Director of Marketing’s Twitter account and Facebook page, while she was hospitalized following a serious car accident. Although Maremont asked her employer to refrain from posting updates to her Facebook page and Twitter account while she was in the hospital and on medical leave, the employer refused to honor her request. Maremont filed a lawsuit against her employer for improperly using her identity to promote its services, even though these same accounts were used in the past to market the employer’s business. In her Complaint, Maremont asserted, among other claims, false endorsement under the Lanham Act and violations of the SCA. On December 7, 2011, the court refused to dismiss both these claims, reasoning, as to the false endorsement claim, that “Maremont created a personal following on Twitter and Facebook for her own economic benefit and also because if she left her employment with [the interior design firm], she would promote another employer with her Facebook and Twitter followers.”5 In refusing to dismiss Maremont’s SCA claim, the Court concluded that there were questions of material fact concerning whether the employer exceeded its authority in obtaining access to Maremont’s personal Facebook and Twitter accounts. This case serves as an important reminder that companies should adopt social media policies that squarely address issues such as the distinction between personal and business social media accounts, who owns the accounts, and who is authorized to speak for the company on social media sites.

Pietrylo et al. v. Hillstone Restaurant Group6 aptly illustrates the limits of employer monitoring of its employees’ online activities. In this case, two restaurant employees set up an invitation-only MySpace chat room specifically to “vent about any BS we deal with [at] work without any outside eyes spying in on us.” One restaurant manager accessed the chat room through her MySpace profile on an employee’s home computer. Other managers were given the password after an employee felt “she would have gotten in some sort of trouble” if she did not comply. The chat room posts included sexual remarks about management and customers, jokes about some of the specifications that the restaurant had established for customer service and quality, and references to violence and illegal drug use. Because the remarks were found to be offensive and violative of company policy, the two employees principally responsible for the chat room were terminated.

The New Jersey Appeals Court rejected the restaurant’s argument that the SCA did not apply, as the access was authorized. According to the Appeals Court, it was a jury question as to whether, under the circumstances, the obtaining of the password was coerced. At trial, the jury found that the restaurant did, in fact, violate the SCA, and that the employees’ privacy interests were violated as a result of the unauthorized viewing of their chat room posts.7

In 2010, in the case of City of Ontario v. Quon,8 the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously held that a public employer’s review of an employee’s text messages on an employer-issued pager was a reasonable search under the Fourth Amendment. After noticing that its employee Jeff Quon, a City of Ontario, California Police Sergeant and SWAT team member, had an excessive number of text messages, the city asked its service provider for copies of the text messages from Quon’s phone. The city found that many of the messages received and sent on Quon’s pager were not work-related, and some were sexually explicit (between Quon and his wife and his mistress). After being allegedly disciplined, Quon filed suit, claiming that his Fourth Amendment privacy rights had been violated.

After a jury trial, a federal district court in California held that the city did not violate Quon’s Fourth Amendment rights. A U.S. federal Appeals Court disagreed, concluding that, although the search was conducted for “a legitimate work-related rationale,” it “was not reasonable in scope.”9 Notably, the Appeals Court also held that the service provider violated the SCA when it provided the employee’s text messages to the employer, without the employee’s consent.

As to the alleged Fourth Amendment violation (the SCA claim not being accepted for further appeal), the Supreme Court reversed, holding that the employer had a right to see text messages sent and received on the employer’s pager, particularly as the city had a policy providing that text messages would be treated like emails, so employees should have no expectation of privacy or confidentiality when using their pagers. Although the Supreme Court was cautious to narrowly limit its decision (and not to elaborate “too fully on the Fourth Amendment implications of emerging technology before its role in society has become clear”10), the case is nonetheless instructive to public and private employers alike, as it serves as a reminder for employers to have clear policies specifically reserving their right to monitor employee usage of Internet, e-mail and text messages, and establishing that employees should have no expectation of privacy in these communications when conducted on company-issued equipment (such as computers and cell phones).

Monitoring employee’s off-duty social media conduct may also expose the employer to liability under state privacy laws. Several states have enacted lifestyle protection laws that prevent employers from prying too far into the personal lives of their employees, particularly when the information found has no bearing on the employer’s business interest, the employee’s job performance, or a bona fide occupational requirement.

For example, Colorado forbids termination of employees based on any lawful activity conducted off employer’s business premises during nonworking hours;11 North Dakota prohibits discharging, and failing or refusing to hire if based on lawful off-duty conduct during nonworking hours;12 and California provides that “[n]o person shall discharge an employee or in any manner discriminate against any employee or applicant for employment because the employee or applicant engaged in any [lawful conduct occurring during nonworking hours away from the employer’s premises].”13 Note, however, that, except for California, these prohibitions do not apply when an employee’s off-duty behavior undermines a bona fide occupational requirement, an employee’s job responsibilities, or an employer’s essential business interests.

How far an employer may pry into its employees’ off-duty social lives is perhaps best illustrated by the case of Johnson v. Kmart.14 In this case, 55 plaintiffs brought an action for invasion of privacy based on an unauthorized (and secret) intrusion into their seclusion—that is, a tort which generally consists of an intrusion, offensive to a reasonable person, and in an area where a person is entitled to privacy. Kmart hired private investigators to pose as employees in one of its distribution centers to record employee conversations and activities not only at work, but also at social gatherings outside of the workplace. The reports contained highly personal information, including employee family matters (for example, the criminal conduct of employees’ children, incidents of domestic violence, and impending divorces); romantic interests/sex lives (sexual conduct of employees in terms of number/gender of sexual partners); and personal matters and private concerns (employee’s prostate problems, paternity of employee’s child, characterization of certain employees as alcoholics because they drank “frequently”).

The Appellate Court of Illinois denied Kmart’s motion for summary judgment—that is, Kmart’s request for a judgment in its favor as a matter of law—because the court found a material issue of fact (requiring jury resolution) existed regarding whether a reasonable person would have found Kmart’s actions to be an offensive or objectionable intrusion. Although the employees willingly provided these personal details to the investigators, the means employed by Kmart to induce the employees to reveal this information were deceptive, particularly as Kmart admitted that it had no business justification for gathering information about its employees’ personal lives. According to the court, “A disclosure obtained through deception cannot be said to be a truly voluntary disclosure. Plaintiffs had a reasonable expectation that their conversations with ‘coworkers’ would remain private, at least to the extent that intimate life details would not be published to their employer.”15

To avoid a claim of invasion of privacy, employers should generally refrain from monitoring their employees’ off-duty social activity.

Similarly, employees using social media do not expect their employer to covertly or deceptively peer into their private social lives. Rather, employees have a reasonable expectation of privacy that their employers will not secretly spy on them, whether in the real or virtual world. To avoid a claim of invasion of privacy, employers should generally refrain from monitoring their employees’ off-duty social activity.

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

An employee’s reasonable expectation of privacy in an employment setting is a function of a variety of factors, including (most importantly) whether an employer has a policy notifying its employees that the employer monitors their use of internet, email (both web-based, personal email accounts and employer-provided accounts), telephones, and the like, for legitimate work-related reasons. In Stengart v. Loving Care Agency, Inc.,16 for example, the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that an employee did not waive the protection of the attorney-client privilege with respect to personal emails sent to her attorney from a company-issued laptop because she had a reasonable expectation that the correspondence would remain private. In this case, the plaintiff, Marina Stengart, the former Executive Director of Nursing at the defendant’s home care services company, brought a discrimination claim against her former employer.. Prior to her resignation, Stengart communicated with her attorney about a potential action against her employer using her personal, password-protected Yahoo email account. (She never saved her Yahoo ID or password on the company laptop.) After Stengart filed suit, the company extracted and created a forensic image of the hard drive from plaintiff’s computer. In reviewing Stengart’s Internet browsing history, the employer was able to discover and read numerous email communications between Stengart and her attorney. Although the employer had an electronic communications policy disclosing that it may access and review “all matters on the company’s media systems and services at any time,” and that all e-mails, Internet communications, and computer files are the company’s business records and “are not to be considered private or personal” to employees, the New Jersey Supreme Court found that this was insufficient to vitiate Stengart’s reasonable expectation of privacy in the emails she sent to her attorney. According to the court:

• The employer’s policy failed to give express notice to employees that messages exchanged on a personal, password-protected, web-based e-mail account are subject to monitoring if company equipment is used. Although the policy states that the employer may review matters on “the company’s media systems and services,” those terms are not defined.

• The policy does not warn employees that the contents of personal, web-based e-mails are stored on a hard drive and can be forensically retrieved and read.

• The policy creates ambiguity by declaring that e-mails “are not to be considered private or personal,” while also permitting “occasional personal use” of e-mail.

The Stengart decision triggered a paradigm shift throughout the country dispelling the commonly-held belief that companies automatically own all electronic information found on their computers, and can use such information however they desire. Nonetheless, while not full-proof, a clearly worded and consistently enforced policy outlining what electronic communications (including those conducted on social media sites) are subject to employer monitoring is the best means to overcome any expectation of privacy that an employee may have in such communications.

Employer Regulation

As a general rule, courts have found employers will be held liable for the online actions of employees on company computers,17 except where the employers took proactive steps to prevent misuse.

For example, in Yath v. Fairview Clinics,18 an employee of a clinic disclosed to others that a patient had a sexually transmitted disease and a new sex partner other than her husband. This information was later posted on MySpace. The court declined to hold the employer vicariously liable for the acts of the employee in these circumstances because the employee’s actions were not foreseeable, particularly as MySpace is a blocked website at the hospital, meaning that employees cannot access the site on the company’s computer while at work.

Similarly, in Delfino et al. v. Agilent Technologies, Inc.,19 a California Court of Appeals held that the employer was not liable for its employee’s threatening messages (sent by email and posted on Internet bulletin boards), even though the employer’s computers were used to send such messages. The court so ruled because the employer promptly terminated the employee upon discovering its computer systems were being used to send the messages. (The court also held that an employer that provided its employees with Internet access was among the class of parties potentially immune under § 230 of the Communications Decency Act [CDA] for cyber-threats transmitted by its employees.) (The CDA’s impact on social media communications is discussed in Chapter 6, “Managing the Legal Risks of User-Generated Content.”)

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

Social media posts can also give rise to hostile work environment claims, even if the posts were made during off-work hours. Employers have a duty to prevent such misconduct (via policies and training), and to take prompt and reasonable corrective action when they learn of it. For the majority of courts, an employer is deemed to have notice (actionable awareness) of hostile/harassing conduct taking place in any company-sponsored online forum (for instance, an intranet chat room) even if the employer is unaware of such conduct in fact. With regard to private employee conduct online, employers do not have an obligation to persistently monitor or ferret out inappropriate conduct on the Web. However, an employer may be deemed to be on constructive notice (legal term for could have had and should have had actionable awareness) of what is taking place on private social media sites if its managers have access to these sites (for example, a manger is Facebook friends with several of the company’s employees).

Employee Discipline for Social Media Use

Reprimanding or firing employees for comments they make in social networks is justifiable in some circumstances, but illegal in others. Understanding the differences between these scenarios when disciplining your employees for inappropriate conduct in social networks is therefore imperative.

Reprimanding or firing employees for comments they make in social networks is justifiable in some circumstances, but illegal in others.

The National Labor Relations Board’s (NLRB) emerging position that employee discipline over social media usage may violate Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA),20 a federal labor law that prohibits companies from violating a worker’s right to engage in protected, “concerted activity” with co-workers to improve working conditions,21 presents employers with increasing danger when disciplining employees over their use of social media. Although concerted activity generally refers to two or more employees acting together to address a common employment-related concern, the NLRA also protects instances of concerted activity wherein a single employee’s actions, on behalf of others, are a reasonable form of protest that will affect other employees.

![]() Note

Note

The NLRA prohibits employers from disciplining employees for discussing working conditions (such as wages, benefits, and the like), regardless of whether or not the employee is a member of a labor union. In other words, employers of nonunion workforces also have to ensure that adverse employment decisions comply with the law.

The following is a summary of the recent enforcement actions brought by the NLRB regarding possible violations of the NLRA arising from employer discipline for alleged employee misuse of social media. The lesson to be gleaned is that such discipline needs to be conducted with care.

Ambulance Service Provider

In October 2010, the NLRB filed a complaint22 against American Medical Response of Connecticut, Inc. (AMR), an ambulance service, alleging that the company violated Section 7 of the NLRA when it discharged an emergency medical technician for violating the company’s social media policy, which provided, in relevant part, as follows:

• “Employees are prohibited from posting pictures of themselves in any media, including but not limited to the Internet, which depicts the Company in any way, including but not limited to a Company uniform, corporate logo or an ambulance, unless the employee receives written approval from the [Company] in advance of the posting.”

• “Employees are prohibited from making disparaging, discriminatory or defamatory comments when discussing the Company or the employee’s superiors, co-workers and/or competitors.”

In this case, the discharged employee posted disparaging comments on her Facebook page about her supervisor and criticized the company for its decision to make that person a supervisor in the first place, insinuating that the company allowed a “psychiatric patient” to be a supervisor. The Facebook posting drew comments from the employee’s co-workers, to which the employee responded.

The NLRB took the position that the company’s social media policy, along with the discharge of the employee, violates the NLRA because the employee and her co-workers were simply discussing their working conditions. As the NLRB observed, the policy was impermissibly overbroad, in so far as it restricted employees from engaging in protected activities, such as “posting a picture of employees carrying a picket sign depicting the Company’s name, or wearing a t-shirt portraying the company’s logo in connection with a protest involving the terms and conditions of employment.”23

The case was subsequently settled, as part of which AMR agreed to narrow the scope of its social media policy so that it does not improperly restrict employees from discussing their wages, hours, and working conditions with co-workers and others while not at work.

Chicago Luxury Car Dealer

In May 2011, the NLRB issued an unfair labor practice complaint against a Chicago-area luxury car dealer alleging that the company illegally terminated a salesman after he posted photos and comments on Facebook criticizing the dealership for only offering its customers hot dogs and bottled water at a sales promotional event.24 Even after he removed the posts at the dealership’s request, the salesman was still terminated the following week. The NLRB alleged that the employee’s post was voicing the “concerted protest and concerns” of several employees “about Respondent’s handling of a sales event which could impact their earnings.”25

However, on September 28, 2011, an administrative law judge (ALJ) with the NLRB issued an opinion holding that, while the NLRA protected the employee’s sarcastic post, the dealership’s termination decision was still lawful because it was based on other, unprotected Facebook content.26 In the opinion, the ALJ noted that the NLRB had previously rejected the same argument in cases where employees’ protected speech and tone were disparaging, unpleasant, mocking, sarcastic, satirical, ironic, demeaning, or even degrading. The decision is an important reminder for employers that when protected and unprotected content appear on the same social media site the protected content does not immunize the employee from discipline based on the unprotected content, provided that the unprotected speech was the real reason for the disciplinary decision.

Employee rants are hardly a recent phenomenon. However, the proliferation of social media sites targeted at disgruntled employees—such as www.jobvent.com, www.hateboss.com, www.fthisjob.com, and so on—represents a particularly thorny dilemma for employers wanting to curtail such speech. While social media policies often include broad provisions to limit negative, offensive, or disparaging statements related to employment, employers should review their policies for overbroad statements regarding employee speech. Because the NLRA prohibits employers from disciplining employees for discussing working conditions, regardless of whether the employees are members of a labor union (or not), all employers need to reexamine their social media policies to make sure they comply with the law.

Not every job-related grievance an employee may post on the Internet is protected. The NLRB continues to require that the employee’s speech posted on social media be related to protected concerted activity (that is, encouraging workers to engage in activity to better the terms and conditions of their employment) before it will protect that speech from employer discipline. To be considered concerted, the activity must have been engaged in with or on the authority of other employees, and not solely by and on behalf of the employee himself.27 While this is a highly fact-specific determination, concerted activity has been found when the circumstances involve group activities, whether the activity is formally authorized by the group or otherwise.28 Individual activities that are the “logical outgrowth of concerns expressed by the employees collectively”29 are also considered concerted.

Advice Memoranda

In July 2011, the NLRB’s Office of the General Counsel issued three advice memoranda that clarified the NLRB’s position on when it is appropriate to discipline an employee who engages in misconduct through social media.

Advice Memorandum 1: JT’s Porch Saloon

The first advice memoranda, JT’s Porch Saloon,30 addressed a charge filed by a bartender at an Illinois restaurant. Under the employer’s tipping policy, waitresses do not share their tips with the bartenders even though the bartenders help the waitresses serve food. During his employment, the aggrieved employee complained to a fellow bartender about the tipping policy, and she agreed that it “sucked.” However, neither of them, or any other bartender, ever raised the issue with management. Instead, several months later, the aggrieved bartender had a Facebook conversation with his stepsister, a nonemployee, wherein the bartender complained that he had not had a raise in 5 years and was doing the waitresses’ work without the benefit of tips. He also posted derogatory comments about the restaurant’s customers, calling them rednecks and stating that he hoped they choked on glass as they drove home drunk.

Although the bartender’s Facebook comments did address terms and conditions of his employment, the NLRB found that this Internet activity was not concerted in nature and therefore was not protected. The memorandum pointed out that the bartender did not discuss the social media posting with any of his co-workers either before or after it was written and that none of his colleagues responded to the posting. Further, the bartender made no attempt to initiate group action to change the tipping policy or to raise his complaints with management. The comments were simply to his stepsister. The NLRB therefore concluded that the employer’s decision to terminate the employee (via Facebook, ironically enough) was not an unfair labor practice.

Advice Memorandum 2: Wal-Mart

In the second advice memorandum, Wal-Mart,31 the NLRB held that a customer service employee’s Facebook postings criticizing his manager were not concerted action, where the posting included vulgar terms for the manager and subsequent messages of support from fellow employees. In this case, the employee’s postings stated, “I swear if this tyranny doesn’t end in this store they are about to get a wakeup call because lots are about to quit!” The employee also commented, in a posting riddled with expletives, that he would be talking to the store manager about his grievances. A few co-workers responded to his Facebook postings and made supportive replies, such as “hang in there.”

The NLRB General Counsel concluded that even though these posts addressed the employee’s terms and conditions of employment and were directed to co-workers, they did not constitute protected activity. More than “mere griping” is needed. Here, the employee was merely expressing his personal “frustration regarding his individual dispute with the Assistant Manager over mispriced or misplaced sale items.” Therefore, there was no outgrowth of collective concerns, and the employee was not seeking to initiate or induce collective action. The General Counsel also concluded that the co-workers’ humorous and sympathetic responses did not convert the posts to group action because the responses demonstrated their belief that the employee was only speaking on his own behalf.

Concerted activities lose their protection under the NLRA if they are sufficiently opprobrious (outrageously disgraceful or shameful) or if they are disloyal, reckless, or maliciously untrue (that is, made with knowledge of their falsity or with reckless disregard for their truth or falsity). This test may produce seemingly inconsistent and sometimes surprising results. For instance, statements have been found to be unprotected where they are made “at a critical time in the initiation of the company’s” business and where they constitute “a sharp, public, disparaging attack upon the quality of the company’s product and its business policies, in a manner reasonably calculated to harm the company’s reputation and reduce its income.”32 But, stating that a company’s president does his “dirty work ... like the Nazis during World War II”33 or that a supervisor is a “dick” and “scumbag”34 (when not accompanied by verbal or physical threats) was held to be protected.

As a general rule, whether the employee has crossed the line depends on the following:

• Whether the statement was made outside of the workplace and/or during nonworking hours;

• The subject matter of the statement (that is, whether it discusses terms and conditions of employment); and

• Whether the employee’s outburst was provoked by the employer’s unfair labor practices.

Advice Memorandum 3: Martin House

The third advice memorandum, Martin House,35 involved a recovery specialist who worked at a residential facility for homeless people, including those with significant mental health issues. While working an overnight shift, the employee engaged in a conversation with friends on her Facebook wall in which she stated that it was “spooky” to work at night in a “mental institution” and joked about hearing voices and popping pills with the residents. None of the individuals who replied to the recovery specialist’s postings were co-workers, nor was the recovery specialist a Facebook friend with any of her colleagues. She was a Facebook friend, however, with a former client of her employer, who reported her concerns to the employer after she saw the postings. The recovery specialist was discharged for her Facebook postings, which inappropriately used a client’s illness for her personal amusement and which disclosed confidential information about clients.

The NLRB General Counsel determined that the recovery specialist had not engaged in any protected concerted activity. Instead, she had merely communicated with her personal friends about what was happening on her work shift. She did not discuss her Facebook posts with her fellow employees, and only personal friends responded to the posts. The aggrieved employee was not seeking to induce or prepare for group action and her activity did not grow out of employees’ collective concerns. In light of these facts, the employer was within its rights to discharge the employee.

![]() Note

Note

Can an employee’s disparaging 140-character tweet against an employer ever constitute concerted activity protected by the NLRA? In one recent case,36 a Thomson Reuters reporter—in response to a supervisor’s alleged invitation to send Twitter posts about how to “make Reuters the best place to work”—posted the following to Twitter: “One way to make this the best place to work is to deal honestly with Guild members.” This tweet allegedly violated a company policy that prohibited employees from saying anything that would “damage the reputation of Reuters News or Thomson Reuters.” After the reporter was reprimanded for the tweet, the NLRB threatened it would file a case against Thomson Reuters, claiming the employer’s policy and its application to this journalist violated the NLRA because it would reasonably tend to chill employees in the exercise of their right to engage in concerted activity. Rather than face a trial, Reuters agreed to settle the case by adopting a new social media policy that included language referencing employees’ right to engage in “protected concerted activity.”

Lawfully Disciplining Employees

Recognizing the need to clarify when an employer can lawfully discipline an employee for social networking misconduct without violating the NLRA, on August 18, 2011, the NLRB’s Acting General Counsel published a 24-page memorandum summarizing the outcome of investigations into 14 cases involving employee use of social media and employer’s policies governing such use.37 The findings are highly fact specific, but the memorandum emphasized the fact that many of the policies at issue were impermissibly broad, as employees could reasonably construe them to prohibit protected conduct. In other words, a social media policy prohibiting employees from making disparaging remarks when discussing the company or supervisors may be overly broad, whereas the same policy with limiting language informing employees that the policy did not apply to NLRA-protected activity would more likely pass muster.

Further, on January 24, 2012, the NLRB’s Acting General Counsel released a second report38 describing social media cases reviewed by its office, seven of which address issues regarding employer social media policies, and another seven of which involve discharges of employees after they posted comments to Facebook.

The report reconfirms:

• Employer policies should not be so sweeping that they prohibit the kinds of activity protected by federal labor law, such as the discussion of wages or working conditions among employees

• An employee’s comments on social media sites are generally not protected if they are mere gripes not made in relation to group activity among employees.

Based on the continuing wave of legal challenges against social media policies and employment practices, companies should tread carefully before disciplining employees for social networking misconduct. Before an adverse employment decision is made, the following factors (none of which alone are dispositive) should be considered:

• Whether the social media post was submitted during working hours or on the employee’s own time

• Whether the employee is using a social media platform to comment on wages, benefits, performance, staffing levels, scheduling issues, or other terms and conditions of employment

• Whether the social media activity appears to initiate, induce, or prepare for group action (versus mere griping)

• Whether the employee’s co-workers had access to the social media postings

• Whether co-workers responded to or otherwise participated in the social media postings and, if so, whether their responses suggest group action

A policy precluding employees from pressuring co-workers to “friend” them does not violate the NLRA, because such a prohibition is designed to prevent harassment and cannot reasonably be interpreted to preclude social media communications that are protected concerted activity.

In the wake of the first NLRB memorandum, on September 2, 2011, a ruling in the first-ever adjudicated social media firing case was reached in Hispanics United Of Buffalo, Inc. v. Ortiz.39 In this case, an NLRB administrative law judge (ALJ) ruled that Hispanics United of Buffalo, Inc. (HUB) violated the NLRA when it terminated five employees for criticizing a sixth co-worker’s job performance on Facebook, even though the Facebook postings were made on the employees’ own computers outside of working hours.

The first challenged Facebook posting read as follows:

“Lydia Cruz, a coworker feels that we don’t help our clients enough at HUB I about had it! My fellow coworkers how do u feel?”

The co-workers responded through Facebook by making such postings as these:

“What the f. .. Try doing my job I have 5 programs;” What the H..., we don’t have a life as is, What else can we do???;” Tell her to come do mt [my] f...ing job n c if I don’t do enough, this is just dum;” I think we should give our paychecks to our clients so they can “pay” the rent, also we can take them to their Dr’s appts, and served as translators (oh! We do that). Also we can clean their houses, we can go to DSS for them and we can run all their errands and they can spend their day in their house watching tv, and also we can go to do their grocery shop and organized the food in their house pantries ... (insert sarcasm here now)”

The original poster responded:

“Lol. I know! I think it is difficult for someone that its not at HUB 24-7 to really grasp and understand what we do ... I will give her that. Clients will complain especially when they ask for services we don’t provide, like washer, dryers stove and refrigerators, I’m proud to work at HUB and you are all my family and I see what you do and yes, some things may fall thru the cracks, but we are all human love ya guys”

After the targeted employee, Lydia Cruz-Moore, brought the postings to her director’s attention, HUB terminated the employees involved in the posts as they allegedly constituted bullying and violated HUB’s policy on harassment. In concluding that the terminations violated the NLRA, the ALJ stated:

“Employees have a protected right to discuss matters affecting their employment amongst themselves. Explicit or implicit criticism by a co-worker of the manner in which they are performing their jobs is a subject about which employee discussion is protected by Section 7. That is particularly true in this case, where at least some of the discriminatees had an expectation that Lydia Cruz-Moore might take her criticisms to management. By terminating the five discriminatees for discussing Ms. Cruz-Moore’s criticisms of HUB employees’ work, Respondent violated Section 8(a)(1) [which prohibits employers from interfering with, restraining, or coercing employees in the exercise of their Section 7 rights to engage in concerted protests or complaints about working conditions].”40

Notably, the ALJ further concluded, “It is irrelevant to this case that the [terminated employees] were not trying to change their working conditions and that they did not communicate their concerns to [HUB].” 41 According to the ALJ, just as employee complaints to each other concerning schedule changes constitute protected activity, so are discussions about criticisms of their job performance.

![]() Note

Note

Unlike private employers, government employers have the additional obligation of avoiding violating their employees’ First Amendment (and similar) rights by disciplining them for content posted on social media sites, particularly if the online speech is of public concern.

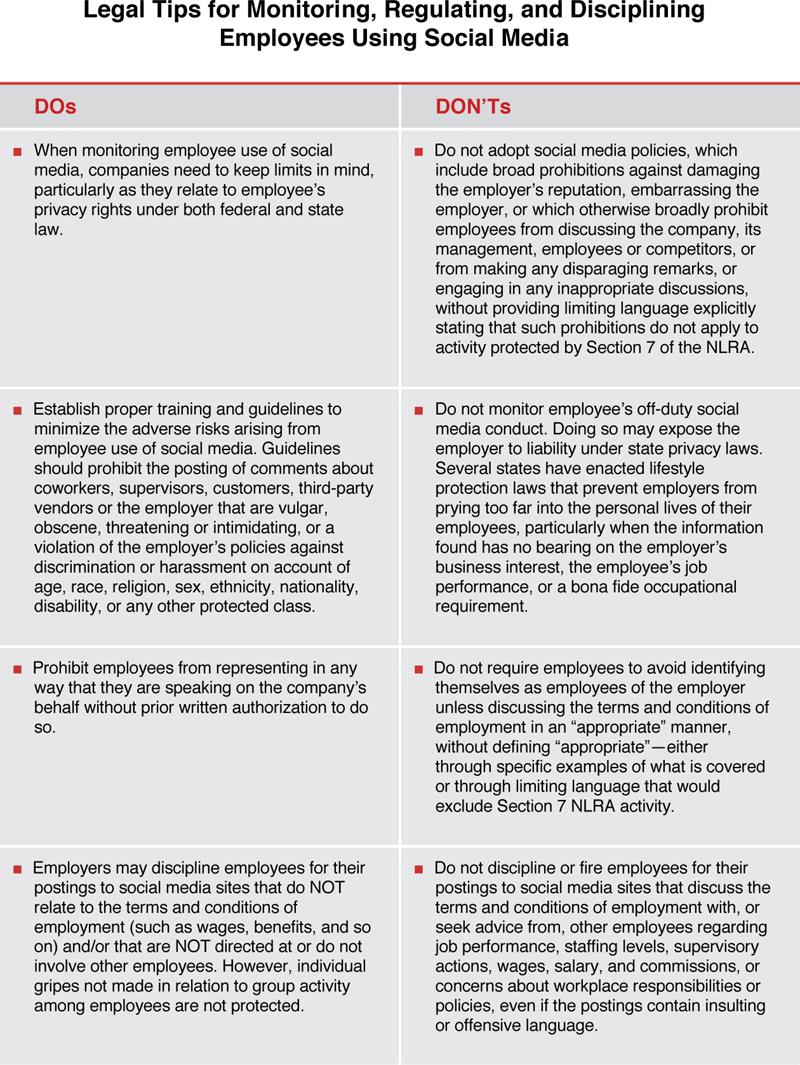

When it comes to mitigating your company’s social media risks, employee monitoring alone is not enough. Here, an ounce of prevention is really worth a pound of cure. Arming employees with social media training and best practices (see Figure 4.1) will not only reduce your company’s legal risks, but also increase the effectiveness of your company’s social media programs and initiatives. Employee social media training therefore makes sense from both a return-on-investment and a legal-compliance perspective.

Figure 4.1 Legal tips for Monitoring, Regulating, and Disciplining Employees Using Social Media.

Chapter 4 Endnotes

1 18 U.S.C. § 2701 et seq.

2 18 U.S.C. § 2701(a)(1):

“(a) Offense. -Except as provided in subsection (c) of this section whoever -

(1) intentionally accesses without authorization a facility through which an electronic communication service is provided;... shall be punished as provided in subsection (b) of this section.”

3 18 U.S.C. § 2701(c)(2):

(c) Exceptions. - Subsection (a) of this section does not apply with respect to conduct authorized - ...

(2) by a user of that service with respect to a communication of or intended for that user;...”

4 Maremont v. Susan Fredman Design Group, Ltd. et al., Case No. 1:10-CV-07811 (N.D.Il. Dec. 9, 2010)

5 See Memorandum Opinion and Order (Document No. 58) (Dec. 7, 2011), in Maremont v. Susan Fredman Design Group, Ltd. et al., Case No. 1:10-CV-07811 (N.D.Il. Dec. 9, 2010)

6 Pietrylo et al. v. Hillstone Restaurant Group, 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 108834 (D.N.J. 2008)

7 Pietrylo v. Hillstone Rest. Group, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 88702, *; 29 THAT ISR. Cas. (BNA) 1438

8 City of Ontario et al. v. Quon et al., 130 S. Ct. 2619 (2010)

9 City of Ontario et al. v. Quon et al., 529 F. 3d 892, 908 (9th Cir. 2008)

10 City of Ontario et al. v. Quon et al., 130 S. Ct. 2619, at 2629 (2010)

11 COLO. REV. STAT. 24-34-402.5 (2006)

12 N.D. CENT. CODE §14-02.4-03 (2004)

13 CAL. LAB. CODE §98.6(a) (2003)

14 Johnson v. Kmart Corp., 723 N.E.2d 1192 (Ill. App. 2000)

15 Id. at 1196

16 Stengart v. Loving Care Agency, Inc., 990 A.2d 650 (N.J. 2010)

17 See, for example, Doe v. XYZ Corp., 382 N.J. Super. 122 (App. Div. 2005) (where employer sued for negligence arising from an employee’s use of company’s computers to post naked pictures of his minor stepdaughter on a child-pornography website, court allowed case to go to trial even though employer had policy against monitoring of or reporting the Internet activities of its employees)

18 Yath v. Fairview Clinics, N. P., 767 N.W.2d 34 (Minn. App. Ct.) (2009)

19 Delfino et al. v. Agilent Technologies, Inc., 145 Cal. App. 4th 790 (Ct. of Appeals of Calif., 6th App. District 2006), cert. denied, 52 U.S. 817 (2007)

20 The National Labor Relations Act, Pub.L. 74-198, 49 Stat. 449, codified as amended at 29 U.S.C. §§ 151–169.

21 Section 7 of the NLRA provides in relevant part:

“Employees shall have the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organization, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection, and shall also have the right to refrain from any or all of such activities....” (29 U.S.C. § 157)

22 American Medical Response of Connecticut, Inc., Case No. 34-CA-12576 (Region 34, NLRB) (Oct. 27, 2010)

23 Id.

24 NLRB v. Knauz BMW, Div. of Advice No. 13-CA-045452 (Jul. 21, 2011)

25 Id.

26 A copy of the ALJ’s opinion is available at http://mynlrb.nlrb.gov/link/document.aspx/09031d45

27 Meyers Industries (Meyers I), 268 NLRB 493 (1984), revd. sub nom Prill v. NLRB, 755 F.2d 941 (D.C. Cir. 1985), cert. denied 474 U.S. 948 (1985), on remand Meyers Industries (Meyers II), 281 NLRB 882 (1986), affd. sub nom Prill v. NLRB, 835 F.2d 1481 (D.C. Cir. 1987), cert. denied 487 U.S. 1205 (1988)

28 Meyers II, 281 NLRB at 887

29 See, for example, Five Star Transportation, Inc., 349 NLRB 42, 43-44, 59 (2007), enforced, 522 F.3d 46 (1st Cir. 2008) (Drivers’ letters to school committee raising individual concerns over a change in bus contractors was a logical outgrowth of concerns expressed earlier at a group meeting.)

30 JT’s Porch Saloon, NLRB Div. of Advice No. 13-CA-46689 (Jul. 7, 2011)

31 Wal-Mart, NLRB Div. of Advice No. 17-CA-25030 (Jul. 19, 2011)

32 Endicott Interconnect Technologies, Inc. v. NLRB, 453 F.3d 532, 537 (D.C. Cir. 2006)

33 Konop v. Hawaiian Airlines, Inc., 302 F.3d 868 (Ct. App., 9th Cir. 2002)

34 American Medical Response of Connecticut, Inc., Case No. 34-CA-12576 (Region 34, NLRB) (Oct. 27, 2010)

35 Martin House, NLRB Div. of Advice No. 34-CA-12950 (Jul. 19, 2011)

36 http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/30/business/media/30contracts.html?_r=1&scp=1&sq=Zabarenko&st=nyt

37 Report of the Acting General Counsel Concerning Social Media Cases Within the Last Year (Memorandum OM 11-74) (August 18, 2011), available at https://www.nlrb.gov/news/acting-general-counsel-releases-report-social-media-cases

38 Updated Report of the Acting General Counsel Concerning Social Media Cases Within The Last Year (Memorandum OM 12-31) (Jan. 24, 2012), available at http://mynlrb.nlrb.gov/link/document.aspx/09031d45807d6567

39 Hispanics United Of Buffalo, Inc. v. Ortiz, NLRB Case No. 3-CA-27872 (Sept. 2, 2011)

40 Id.

41 Id.