Chapter 2

What We Know Now That We Didn’t Know Then

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding how consumer behavior has been viewed and tested for years

Understanding how consumer behavior has been viewed and tested for years

![]() Discovering how people perceive and interpret the world around them

Discovering how people perceive and interpret the world around them

![]() Thinking about people as intuitive consumers, not rational consumers

Thinking about people as intuitive consumers, not rational consumers

Understanding neuromarketing means accepting some radical new ideas that are very different from traditional ways of thinking about consumers, marketing, and advertising. Neuromarketing asks marketing professionals to look at what they do in a very different way.

In this chapter, we give you all the basics you need to know about the old way of thinking about thinking, and the new way that led to neuromarketing. We start by looking at advertising, because advertising research was the first type of marketing research to appear. We review how people have looked at advertising for years, so you have a sense of how this kind of research developed. We show that this research was based on a picture of how the consumer thought and made decisions, called the rational consumer model. Then we show you what brain science has discovered about how people actually perceive and interpret the world — because when you understand that, you know why neuromarketing has emerged hand-in-hand with the new science. Finally, we end the chapter by proposing a new way of thinking about the consumer, the intuitive consumer model.

How We Used to Think about Consumers

In the “good old days” — before brain science started making things more complicated — marketers tended to think of consumers as basically rational information processors, with a little bit of irrational emotion thrown in. This rational consumer model may remind you of a character from Star Trek, pointy-eared and super-logical Mr. Spock. In this section, we use Spock to explain the rational consumer model. Then we explain how early ideas about advertising and marketing were designed around this model of the consumer. We delve into how the effectiveness of marketing and advertising was tested. And we point out the flaws of this old way of viewing consumers.

The rational consumer: Mr. Spock goes shopping

Mr. Spock aspires to be a purely rational and logical decision maker, often to the irritation of fellow crewman Dr. McCoy, the ship’s physician, who relies more on emotions to make decisions. Although consumers actually act a lot more like Dr. McCoy than Mr. Spock, the rational consumer model was the gold standard for years. Consider the attributes that logical Mr. Spock would bring to the shopping experience:

![]() Mr. Spock thinks in terms of information. His brain seeks information, stores information, and retrieves information to make decisions. Emotions play no important role in these processes. Mr. Spock is aware of different brands and products because he’s been collecting and remembering information about them throughout his lifetime.

Mr. Spock thinks in terms of information. His brain seeks information, stores information, and retrieves information to make decisions. Emotions play no important role in these processes. Mr. Spock is aware of different brands and products because he’s been collecting and remembering information about them throughout his lifetime.

![]() Mr. Spock can retrieve this information, completely and accurately, at any point after he has encountered it. His brain operates like a computer hard drive.

Mr. Spock can retrieve this information, completely and accurately, at any point after he has encountered it. His brain operates like a computer hard drive.

![]() Mr. Spock rationally determines his preferences. Among any set of alternatives, Mr. Spock’s preferences are clear, unambiguous, and unchanging (as long as the attributes of the alternatives don’t change).

Mr. Spock rationally determines his preferences. Among any set of alternatives, Mr. Spock’s preferences are clear, unambiguous, and unchanging (as long as the attributes of the alternatives don’t change).

![]() Mr. Spock uses cost-benefit calculations to make a purchase decision at the point of purchase. These calculations determine, for example, whether Mr. Spock will place brand A or brand B in his shopping cart.

Mr. Spock uses cost-benefit calculations to make a purchase decision at the point of purchase. These calculations determine, for example, whether Mr. Spock will place brand A or brand B in his shopping cart.

![]() Mr. Spock’s preferences can be changed if, and only if, he is presented with new information that alters his beliefs about products. Mr. Spock can be influenced to change his behavior, but only if he’s persuaded that his previous beliefs were wrong.

Mr. Spock’s preferences can be changed if, and only if, he is presented with new information that alters his beliefs about products. Mr. Spock can be influenced to change his behavior, but only if he’s persuaded that his previous beliefs were wrong.

![]() Marketing and advertising communications are messages that present rational, logical arguments about brands and products. These communications are designed to persuade Mr. Spock to choose product A over product B at the point of purchase.

Marketing and advertising communications are messages that present rational, logical arguments about brands and products. These communications are designed to persuade Mr. Spock to choose product A over product B at the point of purchase.

![]() The only way marketing and advertising communications can influence Mr. Spock is if he consciously recalls their persuasive arguments. When he remembers them, he can apply them in his purchase decision cost-benefit calculation.

The only way marketing and advertising communications can influence Mr. Spock is if he consciously recalls their persuasive arguments. When he remembers them, he can apply them in his purchase decision cost-benefit calculation.

Modern neuroscience, social psychology, and behavioral economics have raised powerful objections to each of these assumptions. In the next section, we show how these assumptions have impacted marketing and advertising research for over a century.

Rational models for rational marketing to rational consumers

Early pioneers of marketing and advertising research must have had something very similar to this rational consumer model in mind when they formulated the first “advertising effectiveness” theories at the start of the 20th century. These theories were derived from the best model of successful persuasion available at the time, the door-to-door salesman.

In 1903, advertising was famously defined as “salesmanship in print.” Most advertising in those early days was designed to simulate the door-to-door salesman — rapidly conveying a persuasive message for the purpose of converting a prospect into a buyer. Selling through advertising was viewed as a rational, information-based process with no place for emotional appeals or what we now call “creative” in advertising. Like a good door-to-door salesman, a good ad delivered as much information as required, made a persuasive argument for the product, and then explained how to buy the product. That was how it worked.

1. Attention: First, make your customer aware of your product.

2. Interest: Next, pique your customer’s interest by demonstrating the advantages and benefits of your product.

3. Desire: When interest is established, convince your customer that he or she wants or desires your product to satisfy his or her needs.

4. Action: Finally, lead your customer to take the actions required to purchase your product.

Several other models were developed over the following decades by both academics and practitioners that presented different kinds of hierarchy of effects models, all of which were variations of the original AIDA model. For example, in 1961 Roger Colley wrote that “advertising moves people from unawareness, to awareness, to comprehension, to conviction, to desire, to action.”

All these formulas for advertising success viewed the consumer as a rational, information-processing Mr. Spock. Information triggered attention, generated interest, drove desire, and motivated action. The trick of advertising (and later, marketing) was to send messages to the consumer that would guide this journey from unawareness to purchase. The trick of advertising and marketing research, in turn, was to measure whether these effects were occurring.

Measuring effectiveness the old-fashioned way

Over the last century, researchers developed and refined various tools and methodologies to test marketing and advertising effectiveness based on the principles covered in the previous sections. Because researchers believed that the rational consumer was engaged in conscious, rational calculations, the natural way for them to learn about those calculations was to ask consumers what they were thinking.

![]() Interviews: Interviewing techniques include a wide variety of methods, from quick mall intercepts to intensive “depth interviews” that probe the deep sources of consumer desires and needs. All are characterized by a face-to-face interaction between a subject (the person being interviewed) and an interviewer (the person asking the questions).

Interviews: Interviewing techniques include a wide variety of methods, from quick mall intercepts to intensive “depth interviews” that probe the deep sources of consumer desires and needs. All are characterized by a face-to-face interaction between a subject (the person being interviewed) and an interviewer (the person asking the questions).

![]() Focus groups: Focus groups are a natural extension of interviewing. Instead of interviewing one consumer at a time, focus groups bring a group of consumers together under the direction of a moderator who guides a group discussion of the topic under consideration (such as candidate ads, a new product idea, or a comparison of product brands in a particular category). The idea is that the interactive nature of the discussion will uncover additional insights that interviewing consumers in isolation would miss.

Focus groups: Focus groups are a natural extension of interviewing. Instead of interviewing one consumer at a time, focus groups bring a group of consumers together under the direction of a moderator who guides a group discussion of the topic under consideration (such as candidate ads, a new product idea, or a comparison of product brands in a particular category). The idea is that the interactive nature of the discussion will uncover additional insights that interviewing consumers in isolation would miss.

![]() Consumer surveys: Consumer surveys are structured questionnaires designed and administered to elicit answers to questions in a controlled and generalizable way. Properly executed, surveys can accurately estimate the opinions of millions of people from a sample of hundreds. From door-to-door surveys, to telephone surveys, to online surveys, this technique has been the mainstay technique of market research since the 1940s.

Consumer surveys: Consumer surveys are structured questionnaires designed and administered to elicit answers to questions in a controlled and generalizable way. Properly executed, surveys can accurately estimate the opinions of millions of people from a sample of hundreds. From door-to-door surveys, to telephone surveys, to online surveys, this technique has been the mainstay technique of market research since the 1940s.

All these methods share two important attributes: They rely on people’s verbal self-reports (what people say) to identify their attitudes, preferences, and behaviors, and they depend on people’s memories to accurately recall what they’ve done or thought in the past.

When rational models fail

Everybody in the market research business knows that self-reporting measures — whether derived from interviews, focus groups, or surveys — often produce misleading results, send researchers in the wrong direction, and result in ads that don’t have any impact or in products that linger on the shelves.

Traditional market researchers tend to see these problems as fixable with better techniques and controls — for example, more clever question wording in surveys, or larger, more representative samples of consumers being surveyed. These improvements are worthwhile, and they continue to have a positive impact on the quality and usefulness of these methodologies.

Neuromarketing researchers take a more radical view and see things somewhat differently. They recognize a number of flaws in the self-reporting model that can’t be fixed with incremental improvements. These flaws revolve around the concept of accessibility.

Self-report measures assume — following the rational consumer model — that people have conscious accessibility to their mental states (that is, they know what they know). A vast amount of research shows conclusively that people don’t actually know what they know. In fact, people often don’t know the real reasons why they do things, or have certain attitudes or opinions. Their mental processes involving perception, evaluation, and motivation may never reach the level of conscious awareness.

This is the fundamental dilemma of market research that neuromarketing addresses. By bringing the insights of brain science to the world of consumer attitudes and behaviors, neuromarketing is building a portfolio of research techniques and methodologies that are grounded in more realistic assumptions than the models that underlie traditional market research tools.

How People Really See and Interpret the World

In contrast to earlier models, modern neuroscience, social psychology, and behavioral economics give us a much more realistic, but also more complex, understanding of how people think, decide, and act in the real world.

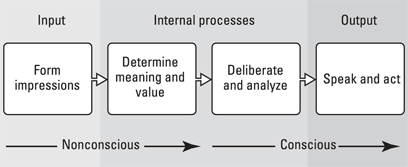

In this section, we present a simplified version of this new model. It doesn’t contain every nuance that academic researchers dwell upon, but it does show how neuroscience and related disciplines provide a more realistic foundation for looking at consumer thinking and behavior. Our model has four key steps (see Figure 2-1):

1. Forming impressions: As we interact with the world around us, our brains form impressions from input we receive through our senses.

2. Determining meaning and value: We determine the meaning and value of the impressions we’ve formed by making rapid mental connections to other things we have stored in memory.

3. Deliberating and analyzing: We deliberate and analyze by engaging in internal “mental conversations” with ourselves.

4. Speaking and acting: We express ourselves by speaking and acting — that is, we engage in actual behavior.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 2-1: Four ways we use our brains.

This model helps us understand the roles played by conscious and nonconscious brain processes, and how they interact:

![]() Our perceptual systems produce impressions in a completely nonconscious way. We have no conscious access to how our brains take in visual, auditory, or other sensory information and turn them into perceived sights, sounds, smells, and so on.

Our perceptual systems produce impressions in a completely nonconscious way. We have no conscious access to how our brains take in visual, auditory, or other sensory information and turn them into perceived sights, sounds, smells, and so on.

![]() Similarly, how we determine meaning and value by connecting our impressions to other concepts and ideas in our long-term memory occurs outside our awareness.

Similarly, how we determine meaning and value by connecting our impressions to other concepts and ideas in our long-term memory occurs outside our awareness.

![]() Deliberating and analyzing are usually conscious processes. They include a wide variety of thinking activities we’re directly aware of, such as memorizing and remembering, calculating, and planning.

Deliberating and analyzing are usually conscious processes. They include a wide variety of thinking activities we’re directly aware of, such as memorizing and remembering, calculating, and planning.

![]() Speaking and acting are usually conscious. Expressions are behaviors that are observable by others, through hearing and seeing us.

Speaking and acting are usually conscious. Expressions are behaviors that are observable by others, through hearing and seeing us.

This simple model has some interesting variations. For instance, it’s possible to get from determining meaning and value to speaking and acting without intervening deliberation or analysis. This is what people normally mean by “doing something without thinking about it.” Examples include learned skills like driving or riding a bicycle.

Forming impressions: How we take in the world around us

“Common sense” tells the average non-scientist that our eyes and ears act like video recorders, creating an accurate recording of the world around us that we then access through memory when and where we need to. The feeling we all have in our conscious minds is that we pretty accurately perceive everything in the world around us, directly and objectively.

But modern brain science tells a different story: People’s impressions of the world are largely created by processes they aren’t aware of, and are very different from the physical signals that enter their sensory organs. For example, the visual images that hit the back of the human eye are actually upside down, but our brains automatically turn them right side up so we can see the world in the most advantageous orientation. Experimenters have put upside-down glasses on people to test this capability, and sure enough, after a couple hours, the brain flips the visual image back to right side up. And when the glasses are taken off, it flips the image back again.

Determining meaning and value: Creating connections in our minds

When we bind impressions with meanings and value, we create concepts or conceptualizations of those impressions. This process of conceptualizing is so fast and automatic that we barely realize it’s happening. But it’s incredibly important to how we interpret and respond to the world.

Early psychologists used to think of conceptualization as just another part of a perception or impression. They assumed that when a person saw a dog, recognizing it as a dog was just a part of seeing it.

What modern brain science tells us is that the process of forming concepts is quite complicated and far from obvious. It involves the rapid and automatic association of a network of category and attribute memories to an impression. The result is that people usually feel that they “know” what they’re looking at instantaneously. Only when our brains encounter impressions at the edge of our implicit categorization models do we become aware of the mental processing involved.

For example, you can usually distinguish a man from a woman without mental effort. But we’ve all been in situations where we’ve seen someone and not been sure if the person was male or female. (Saturday Night Live created a skit about this, with the character Pat.) When you meet a person whose gender isn’t obvious right off the bat, you find yourself searching for attribute cues — body shape, depth of the voice, and so on.

![]() Facilitation: When we bring an idea to conscious awareness, our brains automatically “facilitate” concepts that are related to that idea in memory. These related concepts are not brought to conscious awareness directly, but they are, in effect, prepared for conscious activation if needed.

Facilitation: When we bring an idea to conscious awareness, our brains automatically “facilitate” concepts that are related to that idea in memory. These related concepts are not brought to conscious awareness directly, but they are, in effect, prepared for conscious activation if needed.

![]() Natural assessment: This refers to the brain’s ability to automatically and nonconsciously attach many attributes or characteristics to perceived objects. Some of these are physical properties like size, distance, and loudness, but others are more abstract and can have a big impact on consumer attitudes and behavior, such as similarity, causal tendencies, novelty, emotional assessment (liking and disliking), and mood.

Natural assessment: This refers to the brain’s ability to automatically and nonconsciously attach many attributes or characteristics to perceived objects. Some of these are physical properties like size, distance, and loudness, but others are more abstract and can have a big impact on consumer attitudes and behavior, such as similarity, causal tendencies, novelty, emotional assessment (liking and disliking), and mood.

Facilitation produces distinct signals in the brain, and these signals can be used to determine the strength of association between concepts as they’re being activated. This provides the basis for new measures of brand and product associations in the consumer’s brain, and new tools for monitoring the impact of marketing and advertising on brand concepts over time.

Natural assessment of liking and disliking is an especially important process that people perform innumerable times per day to assign value to the things and situations they experience. Experiments have shown that human beings can translate a positive or negative emotional response into an approach or avoidance physical reaction (for example, leaning forward or away) in less than a quarter of a second — all without being consciously aware that they’re doing it.

The formation of meanings and values involves critical brain processes that neuromarketing methods and tools allow us to observe and measure directly for the first time. Peering into these nonconscious processes creates the potential for a much deeper understanding of the conscious processes we discuss in the next two sections: deliberating, analyzing, speaking, and acting.

Deliberating and analyzing: What we say when we talk to ourselves

Before the discovery of the nonconscious, people believed they had full access to their thoughts and feelings, or at least access enough to be able to express accurate observations about their internal mental states. In the process of deliberation, people simply query their own minds to determine what they’re thinking or feeling about something. Market researchers used to believe that this process was accurate enough to provide good guidance for predicting future consumer attitudes and actions. And so the multi-billion-dollar survey research industry was born.

Modern brain science has demolished this hopeful assumption. People are able to retrieve some things with good accuracy, such as a relatively recent physical action like “Did I take out the garbage yesterday?” But we’re notoriously bad at identifying the causes of our behavior through deliberation. This isn’t because we’re forgetful, but because those causes are literally outside our conscious awareness. We haven’t forgotten them — we just never knew what they were in the first place.

People still use deliberation pretty much every moment of every day. They engage in a constant internal dialog, activating a spectrum of mental activities like:

![]() Retrieving memories: “There’s Marge and her husband. I think his name is Bill.”

Retrieving memories: “There’s Marge and her husband. I think his name is Bill.”

![]() Interpreting the past: “I wonder what she meant by that.”

Interpreting the past: “I wonder what she meant by that.”

![]() Anticipating the future: “What should I make for dinner tonight?”

Anticipating the future: “What should I make for dinner tonight?”

![]() Planning: “If I’m going to make spaghetti, I need to pick up some tomato sauce on the way home from work.”

Planning: “If I’m going to make spaghetti, I need to pick up some tomato sauce on the way home from work.”

![]() Forming intentions: “I’ll pick up some ice cream, too. I usually get vanilla, but today I feel adventurous, so I’ll get chocolate!”

Forming intentions: “I’ll pick up some ice cream, too. I usually get vanilla, but today I feel adventurous, so I’ll get chocolate!”

![]() Evaluating/judging: “That clerk in the grocery store sure was rude.”

Evaluating/judging: “That clerk in the grocery store sure was rude.”

![]() Simulating: “Maybe I would’ve reacted the same way if someone spilled orange juice all over me.”

Simulating: “Maybe I would’ve reacted the same way if someone spilled orange juice all over me.”

![]() Calculating: “Six times $2.49 for each bottle of orange juice is. . . .”

Calculating: “Six times $2.49 for each bottle of orange juice is. . . .”

![]() Reasoning: “If I complain to the clerk, he’ll call his boss. If he calls his boss, I’ll have to admit I dropped the orange juice bottle. If I admit that, his boss will. . . .”

Reasoning: “If I complain to the clerk, he’ll call his boss. If he calls his boss, I’ll have to admit I dropped the orange juice bottle. If I admit that, his boss will. . . .”

![]() Rationalizing: “I must’ve been in a bad mood at dinner tonight because of that upsetting incident at the grocery store.”

Rationalizing: “I must’ve been in a bad mood at dinner tonight because of that upsetting incident at the grocery store.”

Sometimes people seem to jump directly from concepts to actions, with very little deliberation in between. There are two main circumstances in which this happens:

![]() When our actions are derived from acquired skills: Acquired skills are capabilities we’ve learned through practice that become automatic over time. Examples are skills like riding a bicycle or driving a car. Through repetitive learning, these activities convert from conscious, deliberate actions to automatic actions. Acquired skills don’t play much of a role in consumer behavior.

When our actions are derived from acquired skills: Acquired skills are capabilities we’ve learned through practice that become automatic over time. Examples are skills like riding a bicycle or driving a car. Through repetitive learning, these activities convert from conscious, deliberate actions to automatic actions. Acquired skills don’t play much of a role in consumer behavior.

![]() When our actions are derived from habits: Habits, in contrast, play a huge role in consumer behavior. Habits are formed through use and experience. If you’ve been using the same brand of toothpaste for years, and you have no reason to be dissatisfied with it, you’ll probably completely ignore all the other toothpastes on the shelf — despite their bright packaging, promotional displays, and price discounts — and just grab your usual brand.

When our actions are derived from habits: Habits, in contrast, play a huge role in consumer behavior. Habits are formed through use and experience. If you’ve been using the same brand of toothpaste for years, and you have no reason to be dissatisfied with it, you’ll probably completely ignore all the other toothpastes on the shelf — despite their bright packaging, promotional displays, and price discounts — and just grab your usual brand.

Speaking and acting: Finally, we act! (Or maybe just talk about it)

Two kinds of expressions are critical to marketing and market research:

![]() Verbal expression: Self-reporting of opinions, attitudes, preferences, and predictions of future behavior

Verbal expression: Self-reporting of opinions, attitudes, preferences, and predictions of future behavior

![]() Consumer behavior: Shopping, buying, and using products and services

Consumer behavior: Shopping, buying, and using products and services

Market researchers used to think that these two kinds of expressions were closely connected. The rational consumer model assumes that all our decisions and actions are based on conscious deliberative reasoning, which naturally leads to the idea that we can accurately access and verbally express our true reasons for acting one way or another. Much of traditional market research is built on this assumption — if you want to know whether people will buy your product, just ask them.

Alas, this is another hopeful belief that modern brain science has demolished. What the most recent research tells us is that “doing” and “thinking about doing” are only weakly connected. Neuroscience today is busy mapping the paths of these processes through the brain, and social psychology and behavioral economics are busy determining the implications of these differences for individual and collective behavior. The results to date paint a very different picture from the one depicted in the rational consumer model.

Self reporting: “Say it ain’t so”

Verbal expressions, scientists have found, are, in fact, very poor reflections of actual internal mental states. This is hard to accept if you embrace the rational consumer model, but it’s completely understandable if you take into account recent discoveries about nonconscious processes.

The mismatch between verbal expressions and actual mental processes has been known among psychologists for some time. It was first documented by Richard Nisbett and Timothy Wilson in 1977. The gist of what Nisbett and Wilson said is that, when asked what we think, we guess in exactly the same way we guess when trying to figure out what other people are thinking.

Perhaps the fact that we don’t have access to our nonconscious brain processes wouldn’t be so bad for market research if people recognized that they didn’t have access to their nonconscious brain processes and showed some humility in talking about those processes to market researchers. But what Nisbett and Wilson documented way back in the era of disco, and what mountains of later research has confirmed, is this: Not only do we make up plausible explanations of our mental states — what we remember, what we like, why we like it, what we’ll do in the future, and so on —but we vastly overestimate the accuracy of our own reports.

So, not only do we make up stories, but we firmly believe the stories we make up. And we tell those stories to market researchers with the utmost sincerity. And those market researchers take us at our word and produce products that we sincerely told them we would buy. Then everybody scratches their heads when those products sit on the shelf because people didn’t really want them after all.

Consumer behavior: The gold standard of market research data

In contrast to verbal expressions, actual consumer behavior is the real deal of market research. This is data that all marketers ultimately care about — where consumers shop, how they shop, what they buy, how much they pay, how often they buy, what they tell their friends about what they buy, and so on.

Large research companies collect huge amounts of direct consumer behavior data detailed down to the level of individual point-of-sale (POS) purchases by store and by time of day. That data gets crunched through complex algorithms to identify patterns in the fluctuating relationship between how much gets spent on marketing and advertising and how products perform in the marketplace.

A lot of research on consumer behavior — often called market mix modeling in the trade — looks for correlations or causal relationships between marketing expenditures and marketplace performance. In effect, this research “cuts out the middle man” in the process — that is, it cuts out the mental processes in the minds of the millions of consumers who are exposed to the marketing messaging and then spend the money that produces the marketplace performance. It assumes, for the purposes of the analysis, that all those mental processes average out to a “zero effect” over the full dataset of millions of individual instances of consumer behavior.

What we see when we look at this purely input-output behavioral model of marketing is instructive. Gerard Tellis is a researcher who has studied this problem for decades. What Tellis has found is that, when you take the mind of the consumer out of the equation, advertising spending has very little impact on sales.

Tellis has tracked a metric called elasticity of advertising, which measures the percentage impact on sales of a 1 percent change in the level of advertising. In other words, the metric answers the question, “If I increase my spending on advertising by 1 percent, by what percent will my revenues increase?”

The results are rather startling. In his latest calculation of this measure (in 2010), Tellis and his co-authors found that, on average, a 1 percent increase in advertising generates a 0.12 percent increase in short-term sales. This number, calculated in 2010, is over 20 times less than the elasticity of price discounts (calculated in 2005), which showed that a decrease of 1 percent in price resulted — on average — in an increase of 2.62 percent in sales.

With the billions of dollars spent on advertising every year, the net short-term return is minimal. Clearly, we still have much to learn about how to produce more effective advertising.

Although this average figure is rather disappointing, it has a large variance (range of values), because it’s made up of some fabulously successful advertising campaigns, some real dogs, and a lot of campaigns that had no effect on sales whatsoever. What this type of research doesn’t show is why some ad campaigns perform well above average and others perform well below average. From the perspective of marketers and marketing researchers, this is the important question. They don’t want their advertising to be average; they want it to be wildly above average.

In order to separate the winners from the losers, we have to reintroduce the key missing variable in the equation — the mind of the consumer. But as we’ve seen, the mind of the consumer is not well represented by just asking the consumer what he or she was thinking. We need to look for other ways to probe these sources of consumer behavior, and that means going beyond self-reports to understand the nonconscious sources of consumer decisions and behaviors.

Replacing the Rational Consumer Model with the Intuitive Consumer Model

We began this chapter by referencing Mr. Spock, the super-logical first officer on the Starship Enterprise on the TV show Star Trek. We made the case that Mr. Spock could be the poster boy for the rational consumer model that has informed marketing and market research for most of the last century.

Given what we’ve learned from the brain sciences of neuroscience, social psychology, and behavioral economics, it makes sense to consider retiring the rational consumer and replacing it with the much more realistic intuitive consumer model. Once again, we have a character from Star Trek who nicely represents this new ideal — the emotion-driven chief medical officer on the Starship Enterprise, Dr. McCoy. Unlike Mr. Spock, Dr. McCoy makes his decisions based on his emotional responses to situations. He knows in his gut the right thing to do, even if he can’t articulate it clearly. In contrast to Mr. Spock, let’s imagine how Dr. McCoy would go shopping:

![]() Unlike Mr. Spock, Dr. McCoy doesn’t do a lot of deliberate thinking about the products he buys at the grocery store. His brain uses habit, experience, and emotional cues as shortcuts to making decisions. Emotions play the dominant part in these processes. He doesn’t have deep explicit memories about different products and brands, nor could he tell you what claims were made in most advertising he sees.

Unlike Mr. Spock, Dr. McCoy doesn’t do a lot of deliberate thinking about the products he buys at the grocery store. His brain uses habit, experience, and emotional cues as shortcuts to making decisions. Emotions play the dominant part in these processes. He doesn’t have deep explicit memories about different products and brands, nor could he tell you what claims were made in most advertising he sees.

![]() Dr. McCoy retrieves feelings about products and brands and — to a limited extent — factual information, in a loose and spotty manner. Much of this process is below his conscious awareness, so he can’t recount it accurately.

Dr. McCoy retrieves feelings about products and brands and — to a limited extent — factual information, in a loose and spotty manner. Much of this process is below his conscious awareness, so he can’t recount it accurately.

![]() Dr. McCoy’s preferences are largely implicit and based on habit, his friends’ opinions, and his own product experience. He doesn’t usually subject his preferences to careful logical analysis. In fact, he often infers his preferences from his behavior, rather than the other way around. Among any set of alternatives, Dr. McCoy’s preferences may be logically inconsistent — he may prefer brand A to brand B and brand B to brand C, but also prefer brand C to brand A.

Dr. McCoy’s preferences are largely implicit and based on habit, his friends’ opinions, and his own product experience. He doesn’t usually subject his preferences to careful logical analysis. In fact, he often infers his preferences from his behavior, rather than the other way around. Among any set of alternatives, Dr. McCoy’s preferences may be logically inconsistent — he may prefer brand A to brand B and brand B to brand C, but also prefer brand C to brand A.

![]() Dr. McCoy makes most of his purchase decisions spontaneously and without much deliberate thought at the point of purchase. If you asked him why he put brand A instead of brand B in his shopping cart, he probably couldn’t give you a good reason, unless he made one up.

Dr. McCoy makes most of his purchase decisions spontaneously and without much deliberate thought at the point of purchase. If you asked him why he put brand A instead of brand B in his shopping cart, he probably couldn’t give you a good reason, unless he made one up.

![]() Dr. McCoy’s product and brand preferences can be changed, not so much by providing new information as by changing the situation within which he does his shopping. Dr. McCoy’s shopping behavior can be changed, but overt persuasion through logical argument is surprisingly ineffective. When he recognizes that you’re trying to persuade him, he tends to put up cognitive defenses and becomes less, not more, receptive to your message.

Dr. McCoy’s product and brand preferences can be changed, not so much by providing new information as by changing the situation within which he does his shopping. Dr. McCoy’s shopping behavior can be changed, but overt persuasion through logical argument is surprisingly ineffective. When he recognizes that you’re trying to persuade him, he tends to put up cognitive defenses and becomes less, not more, receptive to your message.

![]() Marketing and advertising can have a significant impact on Dr. McCoy, but they tend to do so in nonconscious ways outside his awareness. Dr. McCoy will swear to you that advertising has no effect on his behavior, but like most of his self-assessments, this one will probably be wrong.

Marketing and advertising can have a significant impact on Dr. McCoy, but they tend to do so in nonconscious ways outside his awareness. Dr. McCoy will swear to you that advertising has no effect on his behavior, but like most of his self-assessments, this one will probably be wrong.

![]() The primary way that marketing and advertising influence Dr. McCoy is indirectly, through repetitive association of positive themes and images with the advertised brand or product. Only if he’s actively considering the purchase of a particular product will he consciously seek out, pay attention to, and commit to memory information and persuasive arguments about products in his area of interest.

The primary way that marketing and advertising influence Dr. McCoy is indirectly, through repetitive association of positive themes and images with the advertised brand or product. Only if he’s actively considering the purchase of a particular product will he consciously seek out, pay attention to, and commit to memory information and persuasive arguments about products in his area of interest.

The intuitive consumer model represented by Dr. McCoy creates many new research challenges, but it also provides a much more realistic guide for marketing and market research professionals. Neuromarketing is about embracing and exploring how this model works to develop better predictive theories and measures of how real consumers make real decisions and take real actions in the modern marketplace.

The AIDA model was one of the first translations of sales strategy into advertising strategy. It’s usually attributed to E. St. Elmo Lewis, who formulated it in various writings over the first decade of the 20th century. Lewis’s insight was that advertising worked through a

The AIDA model was one of the first translations of sales strategy into advertising strategy. It’s usually attributed to E. St. Elmo Lewis, who formulated it in various writings over the first decade of the 20th century. Lewis’s insight was that advertising worked through a  Three methodological traditions form the bedrock of traditional market research techniques used to gather information about what consumers think about messages, products, and brands:

Three methodological traditions form the bedrock of traditional market research techniques used to gather information about what consumers think about messages, products, and brands: