Chapter 10

Creating Products and Packages That Please Consumers’ Brains

In This Chapter

![]() Looking at the balance between standing out and fitting in on the shopping shelf

Looking at the balance between standing out and fitting in on the shopping shelf

![]() Understanding what makes product and package designs emotionally compelling to the brain

Understanding what makes product and package designs emotionally compelling to the brain

![]() Tackling the big problem of product innovation that so often fails

Tackling the big problem of product innovation that so often fails

![]() Identifying neuromarketing principles and methods to apply in each of these areas

Identifying neuromarketing principles and methods to apply in each of these areas

In this chapter, we look at how brain science and neuromarketing can help companies create products that people want to buy and packages that stand out on the shelf alongside dozens if not hundreds of alternatives.

First, we examine the precarious balancing act between novelty and familiarity that optimizes a product’s ability to attract attention and consideration on the shelf. Then we reveal some general principles of processing fluency that can be applied to the challenging tasks of product and package design. Finally, we look at product innovation and the ongoing dilemma of why 80 percent of new products fail.

Throughout the chapter, we show how brain science principles introduced in Chapters 5 through 8 can be applied to understand these very practical product and packaging questions, and how neuromarketing techniques can augment and reinforce traditional research techniques.

How New Products Get Noticed

When a shopper approaches a typical shelf in a typical aisle in a typical grocery store or other retail outlet, he can easily find himself gazing at hundreds of different products and packages. Not only are different brands and products competing for attention on the shelf, but a single product may have many variants. A popular laundry detergent, for example, might have 50 different packaging and ingredient variants displayed on the shelf together.

Brands are intangible concepts that build value through creating and reinforcing associations in the brain, but the battle between new and established brands really begins in the tangible world of physical products and packages. In that world, a new product must first get noticed before it can be chosen and bought. And to do that, brain science tells us that it must find a “sweet spot” between novelty and familiarity, two automatic assessments our human brains assign to every object or experience we encounter through our senses (these reactions are described in detail in Chapter 5).

Standing out versus blending in

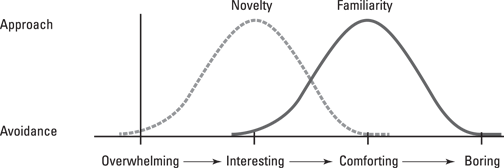

The tension between novelty and familiarity is an old marketing battleground. Marketers know intuitively that too much familiarity leads to boredom and eventual consumer defection, while too much novelty causes a new product to be rejected because consumers can’t see how it fits into a product category they know well. This balance between novelty and familiarity relates to approach and avoidance motivations and is illustrated in Figure 10-1.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 10-1: The spectrum from novelty to familiarity.

Ideally, a new product on the shelf wants to occupy the “interesting” point on the novelty curve — not so novel as to be overwhelming and not so familiar as to be the same as the established products. Similarly, the established product wants to occupy the “comforting” point on the familiarity curve. If it becomes too novel (“interesting”) it can disrupt habitual buyers (as described in Chapter 9) and trigger variety seeking (a response that leading products generally want to avoid), but if it doesn’t refresh itself from time to time, it risks becoming boring, which also opens it up to challenges from alternatives.

![]() Be physically distinct enough to draw involuntary attention at the point of sale

Be physically distinct enough to draw involuntary attention at the point of sale

![]() Signal — either implicitly or explicitly — the goals it helps the consumer achieve

Signal — either implicitly or explicitly — the goals it helps the consumer achieve

Let’s consider an example of how these factors may work together to help a new product stand out on the shelf.

Imagine a consumer approaching her grocery store’s yogurt aisle, where a new yogurt product is present on the shelf. Yogurt is not a habitual purchase for her, nor does she have a product or brand preference in mind. Her initial scan of the shelf typically gives each package only a few milliseconds of gaze time. In that brief moment, the new yogurt needs to make its case — it either attracts her attention or gets passed over, unnoticed. Three package attributes are most important at this moment: color, shape, and brightness.

Standing out is important, but it’s only a first step on the path to purchase. The new yogurt can’t afford to be different simply for the sake of being different. It also must communicate meaningful signals that the consumer can interpret as addressing one of her goals. For example, the package of the new yogurt must easily convey attributes like freshness, tastiness, and healthy eating. This process can have both conscious and nonconscious aspects.

At a nonconscious level, products, brands, and other cues in the shopping environment (like signs and displays) can all trigger nonconscious goal pursuit that may result in a consumer paying more attention to one product on a shelf than others. This type of attention is called bottom-up attention, because it occurs involuntarily as a result of the process of motivational priming described in Chapter 7. Because it’s triggered below the level of conscious awareness, consumers can’t report if or to what extent it impacted their attention to a particular product.

New products can take advantage of learned codes to increase their sense of familiarity. For example, light colors are associated in many markets with various kinds of physically light product attributes, such as reduced fat in a food product. Consumers know that a picture of rising steam communicates a hot bowl of soup, or that stretchy strands of melted cheese communicate tasty, hot pizza. Because of these learned codes, new products can establish some degree of familiarity in their parent category to counterbalance the new and different attributes they also bring to the category.

At a conscious level, consumers also have explicit goals for a product like yogurt that the new product must anticipate in order to attract top-down attention. Unlike bottom-up attention, top-down attention is voluntary, controlled, and driven by conscious goals. In the yogurt example, the consumer comes to the yogurt shelf with existing knowledge, expectations, and goals regarding yogurt, including things like favorite tastes, favorite brands, and previous positive or negative consumption experiences with different yogurt products.

Create and reinforce positive emotional connections through priming, processing fluency, or the activation of existing nonconscious emotional markers

In the next two sections, we look at ways in which both positive and not-so-positive emotional connections can be activated for both new and established products.

Watching out for your neighbors

Products are rarely displayed by themselves. They’re typically grouped into categories — physically in the retail outlet, as well as in the consumer’s mind. Consumers like categorization because it makes it easier for them to make a choice. Whole categories can be eliminated and just one or two may be selected for an in-depth assessment instead of having to make a decision with respect to each individual product. Research has shown that consumers even prefer to have meaningless categories (such as A, B, and C) than no categories at all.

Research suggests that consumers’ implicit reactions to the category in which a product resides can impact their emotional response to the product itself. For example, when a category is well defined in the consumer’s mind, products that conform to established category expectations (learned codes) benefit from processing fluency and are more liked. But when a category is ill formed and vague in the consumer’s mind (for example, think about when you saw your first iPod), novel products can draw more positive emotional responses if they help the consumer better understand the category and its structure.

Context matters in another important way that operates completely outside conscious awareness, through a mechanism called product contagion. In Chapter 7, we describe goal contagion (a tendency for people to nonconsciously “catch” goals being pursued by others in their immediate vicinity). Researchers have identified a similar process operating with products on shelves and in shopping carts.

Leveraging emotional connections

As discussed in Chapter 6, emotional responses — both positive and negative — can drive attention. This is especially true for emotional valence (the perception of an object as more or less liked). Marketers generally recognize that their products and packages can enhance attention in crowded environments like grocery store shelves by activating positive emotions using shape, color, form, symbolism, and other signals. What marketers may be less aware of is the brain science insight that positive emotional connections can also be invoked indirectly through priming, processing fluency, or the activation of existing nonconscious emotional markers (see Chapter 5).

Consider the simple chair: Its shape, its materials, and the room in which it’s located may trigger associations with comfort, health, authority, prestige, nature, youthfulness, nostalgia, and much more. The likelihood that a consumer will notice one chair over hundreds of others in a furniture showroom is increased if — in addition to being visually distinctive and conforming with learned codes that match the consumers’ conscious or nonconscious goals — that chair also triggers an automatic positive emotional response.

Micro-valences appear to emerge from an integration of perceptual fluency and learned associations. These two sources reinforce each other because it’s easier to develop a liking for an object that incorporates positive perceptual features. For example, a consumer might more easily develop positive associations with a shiny, curved, symmetrical teapot than a dull, angular, asymmetrical teapot. In the next section, we show how product and package designs can take advantage of positive associations based on processing fluency to enhance not only attention, but also preference and choice in consumer decision making.

Sometimes a product can trigger emotional connections that aren't typical for the product category. For example, the Italian "gadget" company Alessi (www.alessi.com) creates everyday items for use around the home and office like corkscrews, toothpick holders, nutcrackers, clocks, baskets, fruit bowls, or paperclip holders, adding fun and enjoyment through quirky design elements, which often associate unexpected but meaningful and likeable properties with the product (see Figure 10-2). This is an excellent example of combining emotional triggers and novelty to increase attention and approach motivation.

Photographs courtesy of Photo Alessi Archive

Figure 10-2: Simple items can trigger emotions with surprising associations.

In some instances, the packaging rather than the product is what needs to leverage emotional connections to attract attention at the point of sale. Perfume is an example of a product that’s difficult to distinguish visually but can stand out through distinctive packaging designed to trigger a wide range of associations like sexy, youthful, intriguing, powerful, desirable, confident, playful, eclectic, stylish, traditional, and so forth. To the extent that these associations align with consumers’ goals and learned codes, they can enhance both top-down and bottom-up attention to the package.

![]() Familiarity: Familiar products are less likely to be noticed because of their packaging but more likely to attract attention because of consumers’ prior experience with them or repeated marketing exposures.

Familiarity: Familiar products are less likely to be noticed because of their packaging but more likely to attract attention because of consumers’ prior experience with them or repeated marketing exposures.

![]() Processing fluency: Easy-to-process products and packages can compensate for the negative emotional responses that often accompany novelty by creating a sense of familiarity and trust in the absence of actual prior experience or repeated marketing exposure.

Processing fluency: Easy-to-process products and packages can compensate for the negative emotional responses that often accompany novelty by creating a sense of familiarity and trust in the absence of actual prior experience or repeated marketing exposure.

![]() Approach and avoidance: Emotional micro-valences can influence consumers’ focus of attention and likelihood to select different products.

Approach and avoidance: Emotional micro-valences can influence consumers’ focus of attention and likelihood to select different products.

![]() Nonconscious and conscious goal activation: Products and packages can act as primes to trigger nonconscious goal pursuit. Alignment with learned codes can attract top-down attention and better position a product to satisfy conscious purchasing goals.

Nonconscious and conscious goal activation: Products and packages can act as primes to trigger nonconscious goal pursuit. Alignment with learned codes can attract top-down attention and better position a product to satisfy conscious purchasing goals.

These neuromarketing approaches provide new ways to explore the nonconscious roots of emotion and attention during shopping. They help researchers identify and assess the signals that products and packages send to consumers through subtle design elements like style, color, shape, material, feel, and scent. They provide new metrics for estimating the degree to which a new product or package is making an emotional connection, addressing consumer goals, and standing out on a shelf or display area alongside dozens of competing products.

Neurodesign of Everyday Things

Neuromarketing focuses on understanding how the nonconscious mind influences conscious judgments and decisions. Certain kinds of nonconscious responses, like the degree to which an object can be efficiently and easily understood in the mind (processing fluency), get translated into positive or negative emotional reactions toward that object, or to a feeling of familiarity. Some researchers have begun exploring this relationship from the object side rather than the brain-response side, asking if particular attributes of objects make them more or less easy to process and, therefore, more or less likely to evoke positive emotional responses.

Asking these questions has led to a neuroscience subfield called neurodesign, the study of common design elements of physical objects that people tend to view as beautiful, aesthetically pleasing, and attractive. This work has come to the attention of neuromarketers and has been used to develop insights about design principles for products and packages, as well as new tests to identify winners and losers among candidate designs.

We’re hard-wired for good design

A consumer in a kitchenware shop, looking at displays of coffee cups, glassware, or cutlery, is drawn to some of the products on display while others are immediately excluded from consideration. The same happens when looking across dozens of yogurt containers in the supermarket cooler or when browsing in a furniture or toy store.

Consumers have immediate reactions — positive or negative — as they scan a range of alternatives in a shopping situation. Brain science helps us understand not only how and why these reactions occur (processing fluency, familiarity, novelty, priming), but which characteristics of the items on display tend to trigger those positive or negative reactions, and most powerfully impact the choices and actions that follow from them.

The authors suggest that this effect, which seems to be a part of impression formation and precedes conscious evaluation of the object, may be an evolutionary mechanism that helps us learn the difference between objects that promote safety and objects that represent potential threats. This automatic nonconscious emotional response can be seen as part of the brain’s adaptive “early warning system” that protected our ancestors from thinking too much in the face of danger.

Design tips from the lab

Research on the topic of design and processing fluency is extensive. Much of it has emerged out of work addressing a much loftier question: What is beauty?

Research in social psychology has proposed reconciling these two views by invoking the idea of processing fluency. In a series of studies led by Rolf Reber, Norbert Schwartz, and Piotr Winkielman, evidence has been compiled to show that many objective attributes associated with beauty operate on people’s subjective evaluations because they support processing fluency. In other words, beauty has both objective and subjective sources.

Whether applied to art or everyday objects, this insight has profound implications for design. In the world of product and packaging design, it implies that consumers are hard-wired to prefer designs that can be processed with minimum effort.

Here are some of the key objective features of physical objects that have been found to lift processing fluency, perceived attractiveness, and preference:

![]() Conservation of information: Objects containing less information are easier to process and tend to be judged as more attractive than objects containing more information. Repetitive visual patterns, for example, minimize the amount of information that must be processed to form an accurate impression of an object.

Conservation of information: Objects containing less information are easier to process and tend to be judged as more attractive than objects containing more information. Repetitive visual patterns, for example, minimize the amount of information that must be processed to form an accurate impression of an object.

![]() Symmetry: Objects that are symmetrical around a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal axis contain less (non-redundant) information than asymmetrical objects, so they’re easier to process and usually preferred. Vertical symmetry is easier to process than horizontal, which, in turn, is easier to process than diagonal, so objects arranged vertically are likely to be more appealing than objects arranged horizontally or diagonally.

Symmetry: Objects that are symmetrical around a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal axis contain less (non-redundant) information than asymmetrical objects, so they’re easier to process and usually preferred. Vertical symmetry is easier to process than horizontal, which, in turn, is easier to process than diagonal, so objects arranged vertically are likely to be more appealing than objects arranged horizontally or diagonally.

![]() Contrast and clarity: Figure-ground contrast is the term used to describe the extent to which an object is clearly distinguishable from its background. Higher figure-ground contrast improves perceptual fluency and, therefore, contributes to judged attractiveness. Similarly, objects with crisp, clear lines are easier to process and are judged as more attractive than objects with blurry or indistinct lines.

Contrast and clarity: Figure-ground contrast is the term used to describe the extent to which an object is clearly distinguishable from its background. Higher figure-ground contrast improves perceptual fluency and, therefore, contributes to judged attractiveness. Similarly, objects with crisp, clear lines are easier to process and are judged as more attractive than objects with blurry or indistinct lines.

Additional research has shown that these features only lead to greater liking and judgments of attractiveness when they contribute to processing fluency, but they fail to have this effect when they do not. For example, figure-ground contrast should be more helpful for processing objects when they’re viewed for short periods of time, but not so much when they’re viewed for longer periods. Testing this hypothesis, researchers found that more contrast increased judgments of attractiveness when objects were viewed for less than a second, but didn’t when they were viewed for ten seconds.

Other factors that lift processing fluency, perceived attractiveness, and preference have less to do with the objective features of an object and more to do with a person’s experience and prior exposure to the object:

![]() Repeated exposure: According to the mere exposure effect (see Chapter 5), the more often we’re exposed to an object — almost any object — the more familiar it becomes and the easier it is to process. As a result, we tend to like it more and perceive it as more attractive compared to objects we’re less familiar with.

Repeated exposure: According to the mere exposure effect (see Chapter 5), the more often we’re exposed to an object — almost any object — the more familiar it becomes and the easier it is to process. As a result, we tend to like it more and perceive it as more attractive compared to objects we’re less familiar with.

![]() Implicit pattern recognition: Objects are easier to process when their structure is understood. People’s liking of complex visual patterns is higher when the pattern is predictable than when it isn’t. Sentences that follow known grammatical rules are easier to process than sentences that violate grammatical rules.

Implicit pattern recognition: Objects are easier to process when their structure is understood. People’s liking of complex visual patterns is higher when the pattern is predictable than when it isn’t. Sentences that follow known grammatical rules are easier to process than sentences that violate grammatical rules.

![]() Typicality (average or ideal form): Items that represent an average or ideal version of a category are easier to process and more liked than items that are less typical. This has been shown to hold for a wide variety of objects, including color patches, music, works of art, and human faces.

Typicality (average or ideal form): Items that represent an average or ideal version of a category are easier to process and more liked than items that are less typical. This has been shown to hold for a wide variety of objects, including color patches, music, works of art, and human faces.

![]() Priming: As discussed in Chapter 5, objects that are preceded by an associative prime are more easily processed than non-primed objects, tend to be more liked than non-primed objects, and may even be judged as more familiar than they really are. This effect highlights the importance of context on judgments of attractiveness and liking.

Priming: As discussed in Chapter 5, objects that are preceded by an associative prime are more easily processed than non-primed objects, tend to be more liked than non-primed objects, and may even be judged as more familiar than they really are. This effect highlights the importance of context on judgments of attractiveness and liking.

Expectations play an important role in translating processing fluency into a subjective experience of liking or preference. Researchers have found that fluency has a more powerful impact on liking when its source is unknown and the experience of fluent processing comes as a surprise. In both experimental and real-world settings, if people are aware of the origins of processing fluency, such as an obvious repetition scheme or very simple predictive pattern, fluency’s impact on perceived attractiveness, liking, and preference may be muted. Also, the effect of fluency on subjective judgments and preferences may be diminished if the experience is attributed to an irrelevant source. For example, the usual effect of repetition on perceived liking disappears when people are told that they may like some items more because pleasant music is playing in the background.

Beauty is in the wallet of the beholder

Aesthetic attraction wouldn’t be relevant to marketing if it didn’t translate into consumer decisions and actions.

Apple is often held up as the best example of how good design can translate into exceptional performance in the marketplace. Although there are many elements in Apple’s formula for success, product design is clearly one of them. When Apple introduced the iPod in 2001, it was a $5-billion-per-year computer company. In 2011, following the introductions and several generations of iPhones and iPads, along with new computer designs like the MacBook Air, it was a $150-billion-per-year company. Apple designs across its product lines consistently embody the three aesthetic principles that contribute to processing fluency: conservation of information, symmetry, and contrast and clarity. Apple favors rounded corners, too.

Similar expressions of processing fluency are seen in many other successful product designs, such as those from companies like Bang & Olufsen, BMW, and IKEA. In each of these cases, distinctive product designs are not the only source of the company’s success, but they’re part of a larger pattern of brand connotations and associations that together build a strong brand concept in the consumer’s mind. Apple’s design innovations are naturally reinforced by its strong association with creativity, for example (see Chapter 9).

The impact of product and packaging design on sales can also be illustrated by negative examples. An especially painful case occurred in 2009 for the orange juice brand Tropicana. Seeking to create a new package design that would reinforce the product’s attributes, Tropicana introduced a radical package redesign that replaced the brand’s iconic “orange with a straw coming out of it” central image with a half-revealed glass of orange juice. The new design was launched with heavy marketing, but after two months on the shelf, sales of Tropicana dropped 19 percent, or $33 million, with competitors picking up the lost market share. The company quickly withdrew the new package and reinstated the old one, at a huge (unrevealed) cost. Significantly, when the old packaging reappeared, sales quickly returned to their old levels.

A number of factors may have led to this disaster. Many consumers buy orange juice habitually. Although the company claimed the new packaging failed because consumers had a previously unappreciated (by Tropicana) emotional bond to the old packaging, a neuromarketing assessment probably would’ve revealed that the new package simply got lost among its competitors in the orange juice cooler. The radical change in the appearance of the package made it hard for shoppers engaged in a relatively automatic process to find it, which disrupted their habitual purchasing pattern and triggered a considered purchase decision of an alternative product.

A relatively simple neuromarketing test using eye tracking to trace the gaze patterns of shoppers viewing shelf images with the new and old packaging in place, and then asking them what product on the shelf they would buy, could’ve tested this hypothesis early on in the package design process. If Tropicana marketers and researchers had been more aware of the dynamics of habitual shopping and the importance of implicit decision making in their category, they may have demanded such a simple perceptual test as part of their evaluation process.

Neuromarketing and New Product Innovation

New products are the lifeblood of brands, but more than 80 percent of new products fail, sometimes with a devastating impact on the company’s balance sheet. In this section, we explore why new products fail and what can be done to lift the success rate, drawing on neuromarketing insights, concepts, and methodologies.

Why 80 percent of new products fail

People are terrible at predicting what they’ll do in the future. Research has shown that more than 90 percent of consumers who go on a diet give up the diet and put the weight back on within a year. Similarly, most people don’t follow through with their New Year’s resolutions, despite the sincerity with which they make their plans and commitments on New Year’s Eve.

Apply these lessons to the typical product evaluation focus group. A dozen or so consumers spend 90 minutes in a group discussion, usually dominated by one or two “alpha participants” who feel their opinions are more important than anyone else’s. Toward the end of the session, the moderator asks everyone how likely they are to buy the new product they’ve been discussing. In addition to their general inability to predict what they might do, their answers may be primed by the money they received for their participation, their desire to appear intelligent and insightful, and the fact that they just spent 90 minutes talking about a product they would normally waste little time thinking about.

It isn’t surprising that predictions based on traditional market-research techniques such as focus groups often turn out to be less than accurate. Here are some classic examples of successful products that never would’ve seen the light of day if someone hadn’t chosen to ignore the dismal focus group results:

![]() The Herman Miller Aeron chair was rejected in every market research study, yet when launched, it became the best-selling office chair ever.

The Herman Miller Aeron chair was rejected in every market research study, yet when launched, it became the best-selling office chair ever.

![]() Baileys Irish Cream was rejected by consumers in group after group, but it developed into a huge and enduring success when launched.

Baileys Irish Cream was rejected by consumers in group after group, but it developed into a huge and enduring success when launched.

![]() Researchers told Bang & Olufsen that they could expect to sell 65 units of a new sound system, which, once launched, became its best-selling product.

Researchers told Bang & Olufsen that they could expect to sell 65 units of a new sound system, which, once launched, became its best-selling product.

![]() More than 80 percent of Australian consumers said they would never use an automated teller machine (ATM) when research was conducted prior to their introduction. Today, more than 80 percent of Australian consumers use ATMs on a regular basis.

More than 80 percent of Australian consumers said they would never use an automated teller machine (ATM) when research was conducted prior to their introduction. Today, more than 80 percent of Australian consumers use ATMs on a regular basis.

![]() One of the most popular products in history, the Sony Walkman, was rejected in every market research study but went on to revolutionize the way consumers listened to music while on the move.

One of the most popular products in history, the Sony Walkman, was rejected in every market research study but went on to revolutionize the way consumers listened to music while on the move.

Overcoming bias against the new

Novelty draws attention, but familiarity instills comfort. Processing fluency promotes liking, creates an impression of familiarity, and encourages approach motivation. Novelty violates expectations, promotes vigilance rather than comfort, and, therefore, is associated with caution and avoidance motivation. Novelty also triggers learning, because we try to absorb the lessons of the new and commit those lessons to memory.

In summary, these workings of the human mind reveal that we’re hard-wired to notice new and different things, we focus conscious attention on them, but we tend to distrust them. Over time, as novelty gives way to familiarity and vigilance is replaced by comfort and habit, new things become a part of our everyday lives. But they don’t start out that way.

Within these relationships and associations between novelty, familiarity, vigilance, comfort, learning, motivation, and habit, the brain science explanation for our inability to predict our future likes and dislikes becomes clear. We simply don’t know how and when today’s novelty will translate into tomorrow’s familiarity.

But all is not lost for product and package designers. After all, consumers accept new and innovative products all the time. Old product leaders get displaced and new leaders arise. Whole new categories appear on the scene and sweep the old and familiar aside. How does product innovation overcome our built-in bias against the new?

In what might be called a Goldilocks effect, three key innovation response variables — attention, recall, and liking — have been found to be lowest when an innovation is either insignificant (that is, changes things too little) or disruptive (that is, changes things too much), and highest when an innovation is seen as in between those extremes, neither too big nor too small.

A number of studies in different product categories like furniture, kitchen appliances, and cars have replicated these results. In a 2012 study in the International Journal of Design, researchers found that when participants evaluated a set of chair designs with different levels of novelty in three dimensions (trendiness, complexity, and emotional engagement), the relationship of novelty and aesthetic preference formed an inverted U-shaped curve on each dimension. Chairs rated near the middle on trendiness, complexity, and emotional engagement were all seen as the most aesthetically pleasing.

There are three neuromarketing keys to this approach:

![]() Use design principles that lift processing fluency.

Use design principles that lift processing fluency.

![]() Use messaging (advertising and other marketing communications) to establish new associations between the new product and existing consumer expectations, needs, and wants.

Use messaging (advertising and other marketing communications) to establish new associations between the new product and existing consumer expectations, needs, and wants.

![]() Use repetition to reinforce familiarity and liking through the mere exposure effect.

Use repetition to reinforce familiarity and liking through the mere exposure effect.

When a product is unfamiliar, designers are well advised to include as many familiar design touchpoints as possible. For example, the success of the iPhone and iPad may be due in part to the products mimicking the way consumers are familiar with turning pages in magazines. This familiarity not only makes navigation more intuitive, but also helps trigger positive emotions associated with relaxing with a magazine and a cup of coffee.

The importance of repetition has been documented in many studies. For example, when consumers are exposed to an innovative product for the first time, they tend to favor the familiar. But when they’re exposed to a previously rejected innovation again after a period of time, they tend to prefer the new to the familiar. Studies have confirmed this repetition effect using objective measures (electrodermal activity), as well as subjective ratings by consumers. These findings underline the importance of familiarity and associated processing fluency for increasing perceived liking of new and innovative products.

In the next chapter, we drill down into the relationships among repetition, association building, and advertising to identify ways in which new product ideas can break through the clutter of existing, familiar products to gain consumer acceptance and market share against strong brand and product leaders.

Using Neuromarketing to Test Product and Package Designs

Two neuromarketing methodologies are especially well suited for product and package testing: eye tracking and forced-choice testing. Each of these methods can be supplemented by more complex (and more expensive) brain and body measures to gain additional understanding of the emotional underpinnings of gaze and choice behavior, if such deeper insights are required by the research questions being asked.

The eyes have it: Eye tracking and design testing

Because much of the purpose of product and package design is to attract attention, eye tracking is a natural technology for testing. Modern eye-tracking solutions provide a real-time record of where and when visual attention is directed, as well as how pupil dilation changes over time, a useful indicator of emotional arousal.

Eye tracking records three main types of eye movement data that provide a glimpse into the mental processes that underlie eye movement while looking at an object or scene, such as a product in isolation or a store shelf full of competing products:

![]() Fixations: These are moments when eye movement is relatively stationary. Fixations tend to be associated with information acquisition. The frequency, locations, durations, and order of fixations are all useful measures for understanding how attention is being allocated while viewing an image.

Fixations: These are moments when eye movement is relatively stationary. Fixations tend to be associated with information acquisition. The frequency, locations, durations, and order of fixations are all useful measures for understanding how attention is being allocated while viewing an image.

![]() Saccades: These are rapid eye movements from one point in a scene to another. Information acquisition isn’t occurring during saccades, but different types of saccades provide clues to engagement and effort in interpreting an image. For example, saccades that backtrack to points in an image previously viewed may indicate confusion or processing difficulty (lack of fluency).

Saccades: These are rapid eye movements from one point in a scene to another. Information acquisition isn’t occurring during saccades, but different types of saccades provide clues to engagement and effort in interpreting an image. For example, saccades that backtrack to points in an image previously viewed may indicate confusion or processing difficulty (lack of fluency).

![]() Blink rate and pupil size: If brightness doesn’t vary while viewing, pupil dilation can be a measure of interest or engagement. Blink rates are also indicative of mental processes. Slower blink rates can indicate processing effort, and faster blink rates can indicate fatigue or confusion.

Blink rate and pupil size: If brightness doesn’t vary while viewing, pupil dilation can be a measure of interest or engagement. Blink rates are also indicative of mental processes. Slower blink rates can indicate processing effort, and faster blink rates can indicate fatigue or confusion.

The two most important types of tasks consumers perform while shopping are search tasks and choice tasks.

In product and package testing, search tasks usually ask consumers to “find the product on the shelf.” When a consumer is engaged in such a task, eye-tracking results become meaningful and informative. Measuring the “time to first fixation” on the target product is a simple and intuitive indicator of product standout in a competitive set. By varying the size and number of items in the surrounding shelf, and comparing search times in the different contexts, a measure of bottom-up attention can be calculated based on how much longer it takes to find the target item as context size increases.

Choice tasks ask consumers to make a selection or judgment from a set of alternatives, displayed either together or individually. A product “lineup” image is often an excellent source for eye-tracking analysis. How viewers scan the image when asked to select the “best” or the “worst” package can be highly informative, above and beyond the actual choice. When viewing package images individually, eye tracking will reveal different information if consumers are asked different questions (giving them different choice tasks). Researchers have found, for example, that people will scan a package much differently when asked “How attractive is this package?” than when asked “How likely would you be to buy this product?”

Choosing in the blink of an eye

Another neuromarketing technique that’s very useful for evaluating product and package designs is forced-choice testing. In this type of test, consumers are shown images that may differ by only one or two attributes, such as ketchup bottles that are identical except for different-shaped tops or different-colored labels. These images are usually presented two at a time on a screen. Viewers are asked to pick the one they like the best, and to do so as quickly as possible.

The rapid response requirement forces people to rely on their immediate “gut reactions,” thus diminishing the role of conscious deliberation and increasing the impact of nonconscious processes. By creating a sequence of rapid comparisons that vary a small number of attributes at a time, and then reassembling the results into an overall assessment of complete design alternatives, this approach can bypass many of the self-reporting biases that cause overall product or package assessments to go awry.

Forced-choice results are easier to interpret than brain or body measures because they represent actual behavior. This technique has been used to test many aspects of products and packages, including different designs, different elements within a single design, micro-valences, and price sensitivity.

In

In  Because products typically are part of a familiar category, we have to consider the product’s novelty or familiarity in relation to that category. A new product enhances its ability to stand out among more familiar competitors in its category if it can do two things:

Because products typically are part of a familiar category, we have to consider the product’s novelty or familiarity in relation to that category. A new product enhances its ability to stand out among more familiar competitors in its category if it can do two things: Nonconscious goal-priming is learned through the implicit memory process of

Nonconscious goal-priming is learned through the implicit memory process of  Eye-tracking data is critically dependent on the

Eye-tracking data is critically dependent on the