Chapter 4: Selecting and Using Lenses with the Nikon D7100

By far the most important accessory that you can buy for your D7100 is a good lens. Your lenses have a tremendous effect on your image quality, especially with the high-resolution sensors of dSLRs today. The D7100 sensor resolves high amounts of detail and therefore it is important to put high-quality glass in front of it. The lens not only impacts image sharpness but also affects contrast and color. A quality lens is a valuable investment as your lens will likely be in your kit through a number of camera bodies.

A key feature of the D7100 is that the lenses are interchangeable. You can use lenses to achieve visual effects. You can use a wide-angle lens to distort spatial relations and lines, a telephoto to make far-off objects appear closer, or a macro lens to get close up and show detail that can’t be perceived by the unaided human eye.

A high-quality lens is an investment that should outlast many dSLR camera bodies.

Deciphering Nikon Lens Codes

One of the first things that is apparent when shopping for lenses is that there are a lot of letters in the names, such as AF-S DX NIKKOR 18-105mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR. That’s a pretty big name for the kit lens that comes bundled with the D7100. So, what do all of these letters mean? Here’s a straightforward list to help you decipher them:

• AI/AI-S. These are Auto Indexing lenses. They automatically adjust the aperture diaphragm down to the selected setting when you press the shutter-release button. All lenses, including autofocus (AF) lenses made after 1977, are Auto Indexing, but when referring to AI lenses, most people generally mean the older, manual-focus (MF) lenses.

• E. These are Nikon’s budget series lenses. They were made to be used with lower-end film cameras, such as the EM, FG, and FG-20. Although these lenses are compact and often constructed with plastic parts, some of them — especially the 50mm f/1.8 — are of quality. These lenses are also manual focus only. E lenses are not to be confused with Nikon’s Perspective Control (PC-E) lenses.

AI/AI-S and Series E lenses do not allow for auto-exposure or metering because they don’t have a CPU to communicate data with the camera body.

• D. Lenses with this designation convey distance information to the camera to aid in metering for exposure and flash.

• G. These newer lenses lack a manually adjustable aperture ring, so you must set the aperture on the camera body. Like D lenses, G lenses also convey distance information to the camera.

• AF, AF-D, AF-I, and AF-S. All of these codes denote that the lens is an autofocus (AF) lens. The AF-D code represents a distance encoder for distance information; AF-I indicates an internal focusing motor; and AF-S represents an internal Silent Wave Motor.

• DX. This code lets you know that the lens is optimized for use with Nikon’s DX-format sensor.

In Nikon terminology the term FX is used to differentiate full frame cameras from crop-sensor (DX) cameras. FX lenses do not carry the designation on the lens as they can be used effectively on both FX and DX cameras, but the opposite isn’t true.

• VR. This code tells you that the lens is equipped with Nikon’s Vibration Reduction image-stabilization system. Nikon is constantly improving on this feature, and some newer lenses employ a technology known as VR-II or VR-III, which is capable of detecting side-to side, as well as up-and-down motion. All these technologies are simply designated as VR.

• ED. This code indicates that some of the glass in the lens is Nikon’s Extra-Low Dispersion glass, which is less prone to lens flare and chromatic aberrations.

• Micro-NIKKOR. This is Nikon’s designation for its line of macro lenses.

• IF. IF stands for internal focus. The focusing mechanism is inside the lens, so the front of the lens doesn’t rotate when focusing. This feature is useful when you don’t want the front of the lens element to move, such as when using a polarizing filter. The internal focus mechanism also allows for faster focusing.

• DC. DC stands for Defocus Control. Nikon offers only a couple of lenses with this designation. They make the out-of-focus areas in the image appear softer by using special lens elements to add spherical aberration. The parts of the image that are in focus aren’t affected. Currently, the only Nikon lenses with this feature are the 135mm and the 105mm f/2. Both of these are considered portrait lenses.

• N. On some of Nikon’s higher-end lenses, you may see a large golden N. This means the lens has Nikon’s Nano-Crystal Coating, which is designed to reduce flare and ghosting.

• PC-E. This is the designation for Nikon’s Perspective Control lenses. The E means that it has an electromagnetic Auto Indexing aperture control instead of the typical mechanical one found in all other AI lenses.

Lens Compatibility

Nikon has been manufacturing lenses since about 1937 and is well known for making some of the highest-quality lenses in the industry. You can use almost every Nikon lens made since about 1977 on your D7100, although some lenses will have limited functionality. In 1977, Nikon introduced the Auto Indexing (AI) lens. Auto Indexing allows the aperture diaphragm on the lens to stay wide open until the shutter is released; the diaphragm then closes down to the desired f-stop. This allows maximum light to enter the camera, which makes focusing easier. You can also use some of the earlier lenses, now referred to as pre-AI, but the camera’s auto-exposure functions and metering will not work. All exposure settings must be calculated and set manually.

There are a number of apps that allow you to take exposure readings with your smart phone. I use a free one called LightMeter.

In the 1980s, Nikon started manufacturing autofocus (AF) lenses. Many of these lenses are very high quality and can be found at a much lower cost than their 1990s counterparts, the AF-D lenses. The main difference between AF lenses and AF-D lenses is that the AF-D lenses provide the camera with distance information based on how far away the subject is when focused on. Both types of lenses are focused with a screw-type drive motor that’s found inside the camera body.

Nikon’s current line is the AF-S lens. AF-S lenses have a Silent Wave Motor that’s built in to the lens. The AF-S is an ultrasonic motor that allows lenses to focus much more quickly than the traditional, screw-type lenses. It also makes focusing very quiet. Most of these lenses are also known as G-type lenses. These lenses lack a manual aperture ring; you control the aperture by using the Sub-command dial on the camera body.

Nikon’s first incarnation of the Silent Wave Motor is termed AF-I. These lenses are all long, expensive telephoto lenses, but work perfectly with the D7100.

Nikon offers a full complement of AF-S lenses for the D7100, ranging from the ultrawide 10-24mm f/3.5-5.6G to the super-telephoto 800mm f/5.6E.

The DX Crop Factor

The crop factor is a ratio that describes the size of a camera’s imaging area as compared to another format; in the case of SLR cameras, the reference format is 35mm film. If you are newer to photography or are unfamiliar with 35mm film photography, this concept can be confusing. SLR camera lenses were initially designed around the 35mm film format. Photographers use lenses of a certain focal length to provide a specific field of view. The field of view, also called the angle of view, is the amount of the scene that’s captured in an image. This is usually described in degrees. For example, when you use a 16mm fisheye lens on a 35mm camera, it captures almost 180 degrees of the scene, which is quite a bit. Conversely, when you use a 300mm focal length, the field of view is reduced to a mere 6.5 degrees, which is a very small part of the scene. The field of view is consistent from camera to camera because all SLRs use 35mm film, which has an image area of 24mm × 36mm.

With the advent of digital SLRs, the sensor was made smaller (15.6mm × 23.5mm) than a frame of 35mm film to keep costs down because full-frame sensors are more expensive to manufacture. This smaller sensor size was called APS-C or, in Nikon terms, the DX-format. When these same lenses are used with DX-format dSLRs they have the same focal length they’ve always had, but because the sensor doesn’t have the same amount of area as the film, the field of view is effectively decreased. This causes the lens to provide the field of view of a longer focal lens when compared to 35mm film images.

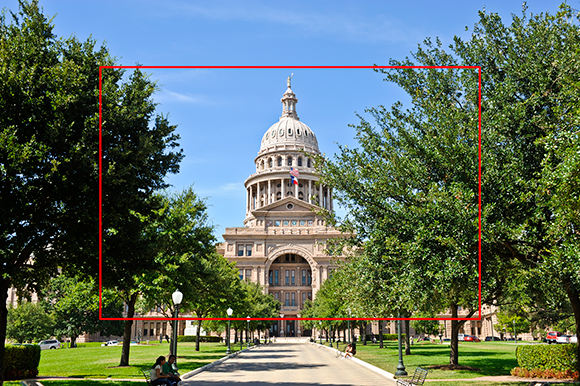

4.1 This image was shot with a 28mm lens on a D700 FX camera, which has a full-frame sensor. The area inside the red square is what would be captured with the same lens on a DX camera, like the D7100.

Fortunately, the DX sensors are a uniform size, thereby supplying consumers with a standard to determine how much the field of view is reduced on a DX-format dSLR with any lens. The digital sensors in Nikon DX cameras have a 1.5X crop factor, which means that to determine the equivalent focal length of a 35mm or FX camera, you simply have to multiply the focal length of the lens by 1.5. Therefore, a 28mm lens provides an angle of coverage similar to a 42mm lens, a 50mm is equivalent to a 75mm, and so on.

An easy way to figure out the DX equivalent focal length is to divide the focal length by 2, and then add the quotient to the original focal length. For example, 10 divided by 2 is 5, and 10 plus 5 equals 15. The equivalent focal length in 35mm (or FX) is 15mm.

Nikon has created specific lenses for dSLRs with digital sensors. These lenses are known as DX-format lenses. The focal length of these lenses was shortened to fill the gap to allow true super-wide-angle lenses. These DX-format lenses were also redesigned to cast a smaller image circle inside the camera so that the lenses could actually be made smaller and use less glass than conventional lenses. The byproduct of designing a lens to project an image circle to a smaller sensor is that these same lenses can’t effectively be used with FX-format and can’t be used at all with 35mm film cameras (without severe vignetting) because the image won’t completely fill an area the size of the film or FX sensor.

There are some upsides to this crop factor. Because all lenses are affected by the crop factor, long focal-length lenses also provide a bit of extra reach. A lens set at 200mm now provides the same amount of coverage as a 300mm lens, which can offer a great advantage for sports and wildlife photography or when you simply can’t get close enough to your subject. Also when using a lens designed for FX cameras, the sensor is only recording image information from the center of the lens where the image is generally sharper.

Another advantage with DX lenses is that with the relative smaller size of DX lenses they can be manufactured with less expense so DX lenses are less expensive than their full-frame counterparts.

Third-Party Lenses

In addition to Nikon, there are other companies that make lenses for Nikon cameras. These lenses are referred to as third-party lenses or sometimes, albeit less frequently, nonmanufacturer lenses. What this means is that the company that makes the lenses isn’t affiliated with the manufacturer (first party) or the purchaser (second party), but is its own entity (third party).

Previously, third-party lenses were considered inferior substitutes to OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) lenses and, in the past that was true. However, in the last 10 years, the digital revolution has brought about a huge resurgence in photography and third-party lens manufacturers have begun to provide very high-quality lenses at lower prices than those sold by Nikon. While most third-party lenses don’t stand up to Nikon’s professional grade lenses as far as build quality, third-party lenses are great alternatives to Nikon’s high-end to lower-level consumer lenses. If you’re looking for a relatively inexpensive, fast, constant-aperture zoom with good image quality that won’t break the bank, a third-party lens is likely the answer.

There are three major players in the third-party lens game: Sigma, Tokina, and Tamron. You may see other brands such as Vivitar and Promaster, but these lenses are usually made by one of the three and rebranded.

Sigma is a company that has been making lenses for more than 50 years and was the first lens manufacturer to make a wide-angle zoom lens. Sigma makes excellent, high-quality lenses. Almost all current Sigma lenses are available with what Sigma calls an HSM, or Hyper-Sonic Motor. This is an AF motor that is built inside the lens and operates in a similar fashion to the Nikon AF-S or Silent Wave Motor. This enables almost all current Sigma lenses to autofocus perfectly with the D7100.

Sigma has recently announced some new high-end lenses: the 30mm f/1.4 DC HSM, 35mm f/1.4 DG HSM, a redesigned 17-70mm f/2.8-4 Macro OS DC HSM, and the 120-300mm f/2.8 DG OS HSM. These are the first lenses that you can plug in to your computer via a USB dock and use Sigma’s proprietary software to update firmware and make microadjustments for focusing. With this is amazing new feature, Sigma is blazing new trails in lens technology. Sigma lenses are a viable and affordable alternative to Nikon’s professional offerings.

Tokina only offers a few lenses that are well regarded. The wide-angle lenses are the 11-16mm f/2.8 Pro DXII, the 12-24mm f/4 Pro DXII, and the 16-28mm f/2.8 Pro FX (this lens also works with full-frame cameras, such as the Nikon D600).

Tamron is another major player in the third-party lens market. Its 17-50mm f/2.8 is one of the most popular inexpensive fast zoom lenses. Tamron has been working out some kinks with its built-in focus motor technology, so there are a few iterations of its most popular lenses. It has a standard screw-type focus technology; a technology referred to as Built-in-Motor (BIM), which focuses very slowly and loudly with an internal focus motor; and the Piezo Drive (PZD) and the Ultrasonic Drive (USD), which are recent additions that are comparable to Nikon’s Silent Wave or AF-S lenses.

Types of Lenses

As I mentioned in the beginning of the chapter, one of the key features of SLR cameras is the ability to use different types of lenses, which allows you to control the aspect in which the image is displayed. There are different types of lenses, which are designed specifically to provide certain effects. Your lens selection allows you to control the artistic direction of your photography.

Wide-angle lenses

The focal-length range of wide-angle lenses starts at about 10mm (ultrawide) and extends to about 24mm (wide angle). Many of the most common wide-angle lenses on the market today are zoom lenses, although a few prime lenses are available. Wide-angle lenses are generally rectilinear, meaning that the lens has molded glass elements to correct the distortion that’s common with wide-angle lenses; this keeps the lines near the edges of the frame straight rather than curved. Fisheye lenses, which are also a type of wide-angle lens, are curvilinear; the lens elements aren’t corrected, resulting in severe optical distortion (which is desirable in a fisheye lens).

Wide-angle lenses have a short focal length, which projects an image onto the sensor that has a wide field of view; this allows you to fit more of the scene into your image. In the past, ultrawide-angle lenses were rare, prohibitively expensive, and out of reach for most nonprofessional photographers. These days, it’s easy to find a relatively inexpensive ultrawide-angle lens. The following list includes some of the ultrawide-angle lenses that work best with the D7100:

• AF-S NIKKOR 10-24mm f/3.5-4.5G. This is a great compact, ultrawide-angle lens. It’s nice and sharp, and balances well on the D7100. The only downside is that it is a little pricey in comparison to third-party lenses of the same caliber.

• Sigma 10-20mm f/3.5 and f/4-5.6 DC HSM. Sigma offers two lenses in this range, the f/3.5 constant-aperture version and the variable-aperture f/4-5.6 version. Neither of these is quite as good as the Nikon lens, but they are more affordable. If you do a lot of low-light, handheld shooting, the f/3.5 version is the better option. If you shoot mostly in daylight or photograph landscapes at smaller apertures with a tripod, the less expensive f/4-5.6 lens is a good option.

• Tokina 11-16mm f/2.8 Pro DXII. This is one of the only ultrawide-angle lenses available with a fast constant aperture. The zoom range is rather limited, but when using an ultrawide lens, most photographers tend to stay at the wide end of the range anyway.

Image courtesy of Nikon, Inc.

4.2 The NIKKOR 10-24mm f/3.5 -4.5G lens.

Wide-angle lenses are great for a variety of subjects. The perspective you get from a wide-angle lens isn’t like anything that can be seen with the human eye. You can use this to create some very bold and interesting images. Once you get used to seeing the world through a wide-angle lens, you may find that you look at your subjects and the world in general in a different way. Whenever I look around I always try to find interesting lines and angles for use with my wide-angle lenses. There are many factors to consider when you use a wide-angle lens. Here are a few examples:

• Deeper depth of field. Wide-angle lenses allow you to get more of the scene in focus than you can with a midrange or telephoto lens at the same aperture and distance from the subject.

• Wider field of view. Wide-angle lenses allow you to fit more of your subject into your images. The shorter the focal length is, the more of the subject you can fit into a shot. This can be especially beneficial when you shoot landscape photos and want to fit an immense scene into your photo, or when photographing a large group of people.

• Perspective distortion. Using wide-angle lenses causes things that are closer to the lens to look disproportionately larger than things that are farther away. You can use perspective distortion to your advantage to emphasize objects in the foreground if you want the subject to stand out in the frame.

• Handholding. At shorter focal lengths, it’s possible to hold the camera steadier than you can at longer focal lengths. At 14mm, it’s entirely possible to handhold your camera at 1/15 second without worrying about camera shake.

• Environmental portraits. Although using a wide-angle lens isn’t the best choice for standard close-up portraits, wide-angle lenses work great for environmental portraits where you want to show a person in his or her surroundings.

Wide-angle lenses can also help pull you into a subject. With most wide-angle lenses, you can focus very close to a subject while creating the perspective distortion that wide-angle lenses are known for. Don’t be afraid to get close to your subject to make a more dynamic image. The worst wide-angle images are the ones that have a tiny subject in the middle of an empty area.

Wide-angle lenses are very distinctive in the way they portray your subjects, but they also have some limitations that you may not find in lenses with longer focal lengths. Here are some pitfalls that you need to be aware of when using wide-angle lenses:

• Soft corners. The most common problem with wide-angle lenses, especially zooms, is that they soften the images in the corners. This is most prevalent at wide apertures, such as f/2.8 and f/4.0; the corners usually sharpen up by f/8.0 (depending on the lens). This problem is most noticeable in lower-priced lenses. The high resolution of the D7100 can really magnify these flaws.

• Vignetting. This is the darkening of the corners in an image. Vignetting occurs because the light necessary to capture such a wide angle of view must come in at a very sharp angle. When the light comes in at such an angle, the aperture is effectively smaller. The aperture opening no longer appears as a circle, but more like a cat’s eye (you can see this effect in the bokeh at the edges of very fast lenses). Stopping down the aperture reduces this effect, and reducing the aperture by 3 stops usually eliminates any vignetting.

• Perspective distortion. Perspective distortion is a double-edged sword: it can either make your images look very interesting or very terrible. One of the reasons that a wide-angle lens isn’t recommended for close-up portraits is that it distorts faces, making the nose look too big and the ears too small. This can make for a very unflattering portrait.

• Barrel distortion. Wide-angle, and even rectilinear, lenses are often plagued with this specific type of distortion, which causes straight lines outside the image center to appear to bend outward (similar to a barrel). This can be undesirable when doing architectural photography. Fortunately, Photoshop and other image-editing software enable you to fix this problem relatively easily.

4.3 A wide-angle shot taken with a Nikon 10-24mm f/3.5-4.5G wide-angle lens at 10mm. Exposure: ISO 500, f/4.5, 1/250 second.

Standard zoom lenses

Standard, or midrange, zoom lenses fall in the middle of the focal-length scale. Zoom lenses of this type usually start at a moderately wide angle of around 16mm to 18mm and zoom in to a short telephoto range between 50mm and 85mm. The 18-105mm kit lens that comes bundled with the D7100 falls under this lens category. These lenses work great for most general photography applications and can be used successfully for everything from architectural to portrait photography. This type of lens covers the most useful focal lengths and will probably spend the most time on your camera. For this reason, I recommend buying the best quality lens you can afford.

Some of the options for midrange lenses include:

• NIKKOR 17-55mm f/2.8G. This is Nikon’s top-of-the-line standard zoom lens. It is a professional lens, and has a fast aperture of f/2.8 over the whole zoom range. It is extremely sharp at all focal lengths and apertures. As with most Nikon pro lenses, the build quality on this lens is excellent. The 17-55mm f/2.8G features the super-quiet and fast-focusing Silent Wave Motor, as well as ED glass elements to reduce chromatic aberration. This is a top-notch lens and is worth every penny of the price tag.

• NIKKOR 16-85mm f/3.5-5.6G VR. This lens is Nikon’s upgrade to the standard DX kit lens (the 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6G VR). This lens offers a little better build quality. It’s also a bit wider at the short end, but you do lose a little bit of reach at the telephoto end when compared to the kit lens.

Image courtesy of Nikon, Inc.

4.4 The NIKKOR 16-85mm f/3.5-5.6G lens.

• Tamron 17-50mm f/2.8 Di II. This is a very popular alternative to the Nikon lens for a fast aperture zoom. There are two versions of the Di II lens: the VC (Vibration Compensation) and non-VC. However, you should be aware that the regular Di version doesn’t have a built-in focus motor and won’t autofocus with the D7100.

• Sigma 17-70mm f/2.8-4 DC HSM OS Macro “C”. This is one of my favorite lenses for DX cameras. It’s easily the most versatile lens I’ve ever owned. It’s relatively fast and good for low-light shooting with Optical Stabilization, it’s very sharp and, although not a true macro lens, it gets you close enough. The best part is that it’s not overly expensive. I recommend this lens over all other standard lenses in its class.

In the standard range for primes, the most popular are the 30-35mm normal lenses. They are referred to as normal because they approximate about the same field of view as the human eye. The Nikon 35mm f/1.8 is a great inexpensive fast normal lens as is the even faster Sigma 30mm f/1.4. I think every photographer should carry a fast prime in his camera bag.

4.5 The The new Sigma 17-70mm f/2.8-4 “C” lens is one of the sharpest zoom lenses I used on the D7100. The macro feature allows you to get great close-up detail especially when using the 1.3X DX crop feature. Exposure: ISO 100, f/16, 1/60 second with SB-900 Speedlight off camera Sigma 17-70mm f/2.8-4 “C” at 70mm (approx. 140mm equiv. with 1.3X DX crop).

Telephoto lenses

Telephoto lenses have very long focal lengths that are used to get closer to distant subjects. They provide a very narrow field of view and are handy when you’re trying to focus on the details of a far-off subject. Telephoto lenses have a much shallower depth of field than wide-angle and midrange lenses, and you can use them to blur out background details to isolate a subject. Telephoto lenses are commonly used for sports and wildlife photography. The shallow depth of field also makes them one of the top choices for photographing portraits.

Like wide-angle lenses, telephoto lenses also have their quirks, such as perspective distortion. As you may have guessed, telephoto perspective distortion is the opposite of wide-angle distortion. Because everything in the photo is so far away with a telephoto lens, the lens tends to compress the image. Compression causes the background to look closer to the subject than it actually is. Of course, you can use this effect creatively. For example, compression can flatten out the features of a model, resulting in a pleasing effect. Compression is one of the main reasons photographers often use a telephoto lens for portrait photography.

A standard telephoto zoom lens usually has a range of about 70 to 200mm. If you want to zoom in close to a subject that’s very far away, you may need an even longer lens. These super-telephoto lenses can act like telescopes, really bringing the subject in close. They range from about 300mm up to about 800mm. Almost all super-telephoto lenses are prime lenses, and they’re very heavy, bulky, and expensive. To keep costs lower, some super-telephoto lenses have a slower aperture of f/4.0.

There are quite a few telephoto prime lenses available. Most of them, especially the longer ones (105mm and longer), are expensive, although you can sometimes find older Nikon primes that are discontinued or used — and at decent prices — such as the NIKKOR 300mm f/4.

4.6 The A long zoom like the Nikon 200-400mm f/4 provides enough reach to bring you close to the action. Exposure: ISO 220, f/5, 1/320 second with Nikon 200-400mm f/4 VR at 360mm.

The following list covers some of the most common telephoto lenses:

• NIKKOR 70-200mm f/2.8G VR II. Nikon’s top-of-the-line standard telephoto lens features Vibration Reduction (VR), which is useful when photographing far-off subjects handheld. This is a great lens for shooting sports or portraits, as well as wildlife.

• NIKKOR 70-200mm f/4G VR III. Nikon’s latest affordable alternative to the 70-200mm f/2.8G VR lens. It is sharp and has a constant f/4.0 aperture. This makes for a smaller, lighter lens when speed isn’t a necessity.

• Sigma 50-150mm f/2.8 DC OS HSM. A more affordable alternative to the 70-200mm VR lens, this Sigma lens is sharp and has a fast, constant f/2.8 aperture.

• NIKKOR 200-400mm f/4G VR. This is a high-power, VR image-stabilization zoom lens that gives you a lot of reach. Its long zoom range makes it especially useful for wildlife photography when the subject is far away. While this lens is quite pricey it’s an invaluable tool for a professional sports or wildlife photographer.

Close-up/Macro lenses

A macro lens is a special-purpose lens used in macro and close-up photography. It allows you to have a closer focusing distance than regular lenses, which in turn allows you to get more magnification of your subject, revealing small details that would otherwise be lost. True macro lenses offer a magnification ratio of 1:1; that is, the image projected onto the sensor through the lens is the exact size as the object being photographed. Some lower-priced macro lenses offer a 1:2 or even a 1:4 magnification ratio, which is one-half to one-quarter of the size of the original object. Although lens manufacturers refer to these lenses as macro, strictly speaking they are not.

Nikon macro lenses are branded Micro-NIKKOR.

One major concern with a macro lens is the depth of field; when you focus at such a close distance, the depth of field becomes very shallow. As a result, it’s often advisable to use a small aperture to maximize your depth of field and ensure everything is in focus. Of course, as with any downside, there’s an upside: you can also use the shallow depth of field creatively. For example, you can use it to isolate a detail in a subject.

Macro lenses come in a variety of focal lengths, and the most common is 60mm. Some macro lenses have substantially longer focal lengths that allow more distance between the lens and the subject. This comes in handy when the subject needs to be lit with an additional light source. A lens that’s very close to the subject while focusing can get in the way of the light source, casting a shadow.

When buying a macro lens, you should consider a few things: How often are you going to use the lens? Can you use it for other purposes? Do you need AF? Because newer dedicated macro lenses can be pricey, you may want to consider some less expensive alternatives.

It’s not absolutely necessary to have an AF lens. When shooting extremely close up, the depth of focus is shallow, so all you need to do is move slightly closer or farther away to achieve focus. This makes an AF lens a bit unnecessary. You can find plenty of older manual-focus (MF) macro lenses that are inexpensive, but that have superb lens quality and sharpness.

Image courtesy of Nikon, Inc.

4.7 The Micro-NIKKOR 40mm f/2.8G macro lens.

Nikon has a strong lineup of macro lenses that offer full functionality with the D7100. They range from normal to telephoto in both VR and non-VR versions and can be found at all price points. The choices range from the 40mm f/2.8G, 60mm f/2.8G, 85mm f/3.5G VR, and the 105mm f/2.8G VR and 200mm f/4 when you need some extra reach.

While Nikon makes a plethora of macro lenses, there are some well regarded third party options available as well. Sigma and Tamron both have good offerings in macro lenses as well. I sometimes use an old Pentax Macro lens, which allows a very high magnification factor of 4:1.

4.8 A macro shot taken with a Pentax Macro-Takumar 50mm f/4.0 at 3:1 magnification. I used an M42 to Nikon adapter to mount the lens. Exposure: ISO 250, f/4, 1/200 second.

Fisheye lenses

Fisheye lenses are ultrawide-angle lenses that aren’t corrected for distortion like standard rectilinear wide-angle lenses. These lenses are known as curvilinear, meaning that straight lines in your image, especially near the edge of the frame, are curved. So, what makes fisheye lenses appealing is the very thing we try to get rid of in other wide-angle lenses — fisheye lenses have extreme barrel distortion. Fisheye lenses cover a full 180-degree area, allowing you to see everything that’s immediately to the left and right of you in the frame. You need to take special care so that you don’t get your feet in the frame, which often happens when you use a lens with a field of view this extreme.

Fisheye lenses aren’t made for everyday shooting, but with their extreme perspective distortion, you can achieve interesting, and sometimes wacky, results. You can also de-fish or correct for the extreme fisheye by using image-editing software, such as Photoshop, Capture NX or NX 2, and DxO Optics. The end result of de-fishing your image is that you get a reduced field of view. This is akin to using a rectilinear wide-angle lens, but it often yields a slightly wider field of view than a standard wide-angle lens.

Two types of fisheye lenses are available: circular and full frame. Circular fisheye lenses project a complete 180-degree spherical image onto the frame, resulting in a circular image surrounded by black in the rest of the frame. A full-frame fisheye completely covers the frame with an image. The 10.5mm NIKKOR fisheye is a full-frame fisheye on a DX-format dSLR. Sigma also makes a few fisheye lenses in both the circular and full-frame variety. The Russian company Peleng also manufactures a decent-quality and relatively affordable, manual-focus fisheye lens. Autofocus is not truly a necessity on fisheye lenses given their extreme depth of field and short focusing distance.

4.9 An image taken with a Nikon 10.5mm fisheye lens. Exposure: ISO 1400, f/4, 1/5 second.

Lens Accessories

A number of lens accessories are designed to work with your existing lenses to make them more useful for different applications. These accessories allow you to save room and weight in your camera bag by essentially allowing you to use one lens for numerous purposes.

Teleconverters

A teleconverter (sometimes referred to as a TC) is a small lens element situated between the camera and the lens. A teleconverter magnifies the incoming image to increase the effective focal length. Teleconverters are quite small, which is why some photographers prefer to use them rather than buy a longer lens. They are generally used to extend telephoto lenses rather than wide-angle or standard lenses; in fact, they aren’t generally recommended for use with those types of lenses.

Teleconverters come in three standard magnifications — 1.4X, 1.7X, and 2X — which magnify your images by 40 percent, 70 percent, and 100 percent. So when using a teleconverter with a 70-200mm f/2.8G, you get effective focal lengths of 98-280mm, 199-340mm, and 140-400mm, respectively. The 1.5X crop factor still applies, which makes the apparent reach of the lens even longer giving you the final equivalent of 147-420mm, 299-510mm, and 210-600mm.

Not all lenses are designed to work with teleconverters. I recommend carefully trying out the teleconverter with your lens before purchasing. With some lenses the rear elements may protrude out far enough to damage the lens or teleconverter so caution is recommended when attempting to couple them.

The upside of using a teleconverter is that you can get more reach out of the lens. This is obvious, of course, but it can get you in closer to unapproachable subjects to capture more detail. You can get more reach without a lot of extra weight (a 600mm telephoto lens is very sizeable). You maintain the lens’s minimum focus distance, which allows you to get near-macro shots.

Another upside is that when coupled with a macro lens, the teleconverter increases your magnification ratio. With a 2X converter you can increase the ratio to 2:1, or double life size.

Of course, there’s no free lunch. The main drawback is that you lose light when using a teleconverter. A 1.4X teleconverter costs you 1 stop of light, a 1.7X about 1.5 stops, and a 2X reduces it by 2 stops. So your 200mm f/2.8 becomes a 400mm f/5.6 with a 2X teleconverter. This may not be bad in daylight, but it can become a liability in low light. A lens with a maximum aperture of f/4, such as a 300mm f/4, would be reduced to an effective aperture of f/8, which is the threshold of the D7100’s ability to autofocus. Previous Nikon cameras only allowed AF on lenses that were f/5.6 or faster, so the D7100 outshines some earlier models when it comes to using teleconverters.

Another drawback to using teleconverters is that the extra glass elements have a detrimental effect on image quality. Images shot with a teleconverter can often appear hazy and lack sharpness. This is why you should purchase the best teleconverters you can get. Unfortunately, the Nikon telelconverters are quite expensive, but they are the best. I’ve used third-party teleconverters that cost much less, and much to my chagrin, none of them holds a candle to the Nikon offerings.

At the end of the day, using teleconverters is an exercise in give and take. If you need the extra length, you need to ask whether the advantages are worth the drawbacks.

Extension tubes

Extension tubes are often mistaken for teleconverters. The placement is the same, but their purpose is much different. Extension tubes are placed between the camera body and the lens, but there are no optical elements involved. An extension tube is an empty tube, the sole purpose of which is to move the lens farther away from the focal plane, allowing it to focus closer on the subject. This allows a standard lens to focus at macro ratios of 1:1 or better.

Extension tubes are an inexpensive add-on to make any lens a macro lens. The upside to extension tubes is that there are no optical elements involved, so there is no degradation in image quality at all, aside from a shallower depth of field. As with teleconverters, there are different sizes that allow different magnifications, and increasing magnification brings a loss of light.

Extension tubes are more effective with wide-angle to standard lenses than telephotos.

There are two kinds of extension tubes: CPU and non-CPU, with the cheapest being non-CPU. Similar to Nikon’s older MF lenses, these tubes have no electrical contacts to relay data to the camera. For extension tubes, you need to use lenses with manual aperture control. If you don’t, the aperture stops down automatically to the minimum aperture. Manual focus and manual exposure are also necessary.

Stepping up a bit, you can get extension tubes with electrical contacts that allow you to autofocus and control your aperture and other settings from the camera as you normally would. Extension tubes are a great alternative to buying a dedicated macro lens, and they also provide excellent image quality because there’s no additional glass between the lens and sensor to interfere.

Close-up filters

On the bottom tier of lens accessories are the close-up filters. They screw right into the filter ring on the front of the camera lens. Similar to extension tubes, close-up filters allow you to focus closer on your subject for getting macro shots. They essentially act as a magnifying glass for your lens. These filters come in a variety of magnifications and can be stacked or screwed together to increase magnification exponentially.

The upside to using close-up filters is that you don’t lose any light. The effectiveness of the lens aperture is also not reduced at all. The downside is that close-up filters reduce image quality and can produce soft images. The image quality degrades further as the lenses are stacked.

As with teleconverters, you are better off purchasing high-quality filters. The glass in the more expensive filters is manufactured more precisely and gives much sharper results than inexpensive filters with low-quality glass. Quality brands include B+W and Heliopan.

Ultraviolet filters

Current dLSR cameras, such as the D7100, have a built-in ultraviolet, or UV, filter in front of the sensor, therefore the usefulness of a UV filter is negated when it comes to the purpose for which it was originally designed. However, many photographers, myself included, still use them. Why, then, would someone decide to use a seemingly useless filter on a lens? The answer is to protect the front element of your lens.

This is one of those hot-button issues that you will find photographers on Internet forums arguing vehemently about — both for and against. The bottom line is that there are good reasons why you should use UV filters and good reasons why you shouldn’t.

The main pro for using a UV filter is the protection you get against scratches on the front element of the lens. Dust, dirt, and debris can get on your lens causing abrasions when you clean the glass using a lens cloth. The UV filter provides a barrier against the debris. This is especially important when shooting near the ocean, as the salty sea spray is extremely abrasive to glass. If you shoot in dusty environments or in damp weather frequently as I do you will appreciate the protection of a UV filter. Take a look at your UV filter after about six months of constant use and you will see what kind of damage it prevents.

There are, however, some cons to using UV filters as well. First thing is that any extra glass you put in front of your lens is going to degrade the image quality. For this reason I only use the best quality multicoated filters. My personal choice is the Rodenstock HR Digital. B+W and Zeiss also make some of the top-rated filters.

Another con to using a UV filter is that adding another piece of glass into the mix also gives light another surface to reflect from, which can lead to increased flare and ghosting. This is another reason I recommend using a high-quality multicoated filter. The coating helps to quell this problem.

It is really up to you to decide whether a UV filter is a necessity. If you find yourself shooting outside in the elements a lot and you need to clean your lens frequently, you may benefit from a UV filter. However, if you’re an indoor shooter mainly working in a clean environment such as a studio you may never need the protection of a UV filter.

Neutral density filters

A neutral density, or ND, filter reduces the amount of light that enters the lens without coloring or altering it in any way. These filters are used in bright sunlight to allow slower than normal shutter speeds to be used to create special effects, such as motion blur. ND filters are also used to reduce light so that a wide aperture can be used in bright sunlight; this technique is used quite a bit in filmmaking.

ND filters come in different densities, called filter factors. These are measured in 1-stop increments and, just as when reducing the aperture or shutter speed by 1 stop, the light is halved. An ND2 filter reduces the light by 1/2, or equal to 1 stop; an ND4 allows only 1/4 of the light to reach the sensor, which is 2 stops; an ND8 permits only 1/8 of the ambient light, which is 3 stops, and so on.

4.10 This photo was taken using a standard neutral density ND8 filter to achieve a slow shutter speed in bright daylight. Exposure: ISO 200, f/11, 1/5 second, using a Sigma 17-35mm lens.

Some filter manufacturers (mostly the high-end ones) use a different scale to measure the density — .01 for 1/3 stop, .02 for 2/3 stop, and .03 for a full stop.

There is also a type of filter called a gradual neutral density filter, or GND for short. This type of filter has a gradient that goes from clear to dark. This type of filter is mostly used in landscape photography to balance the exposure from the bright sky with the darker land, although HDR photography is supplanting this technique for the most part.

A third type of filter, which is becoming increasingly more common these days, is the Variable Neutral Density filter. With this filter you can adjust the amount of ambient light anywhere between 2 and 8 stops by rotating the filter. This allows much more flexibility for different light intensities and you only have to carry around one filter.