Chapter Five

One Great Big Online Market

Smartphones, the Internet and social media function in many ways like a classic bazaar, where goods, services and experiences of all sorts are for sale and where eager hawkers will do everything they can to get your attention. But unlike the classic bazaar, internet hawkers are automated, fiercely smart and relentlessly focused. It's a trillion-dollar market populated by behemoth whales (Apple, Google, Facebook, Amazon) as well as thousands of smaller fish like Netflix, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, Rentalcars.com, Expedia, Orbitz, Walmart, eBay, Target, Best Buy, Etsy, MoMondo, Ryanair, and Delta, to mention just a few.

All of these sites share a common interest—knowing what you want, grabbing your attention as quickly and cheaply as possible and getting you to make the transaction. They also know that success lies in preaching to the choir—they're not interested in expending resources in trying to sell you a guitar if you don't like guitars to begin with. To attract relevant attention at a reasonable cost, the marketers behind search engines, social media and the Internet have developed a wide range of tools to analyze and understand your propensities and interests. They find their targets based on what can be measured and understood about how you use the Internet.

The complexity and level of sophistication of these tools comes as a surprise to most people but we are under much closer scrutiny than is generally known. The fact is that we are all being targeted by the top brains in behavioral science and digital code, and they know how to match your information to the advertisers that are out to sell you goods, services and entertainment.

B.J. Fogg and the Stanford Persuasion Lab

In 1997, a Stanford PhD by the name of B.J. Fogg posed a very interesting question at a conference in Atlanta. After researching how people interact with computers, he realized that students gravitated toward computers that they had gotten good results from, even though objectively speaking, all of the computers functioned identically. Could it be, he wondered, that people relate to computers just as they would with other people?

This simple idea would have wide-ranging implications. Fogg's simple attempt to create better software for students eventually became known as the “Fogg Behavior Model,” and ended up as the weapon of choice for anyone who wants to hypnotize you online with anything from a sales pitch to a political agenda. As Ian Leslie of The Economist puts it:

Fogg called for a new field, sitting at the intersection of computer science and psychology, and proposed a name for it: “captology” (Computers as Persuasive Technologies). Captology later became behaviour design, which is now embedded into the invisible operating system of our everyday lives. The emails that induce you to buy right away, the apps and games that rivet your attention, the online forms that nudge you towards one decision over another: all are designed to hack the human brain and capitalise on its instincts, quirks and flaws. The techniques they use are often crude and blatantly manipulative, but they are getting steadily more refined, and, as they do so, less noticeable.1

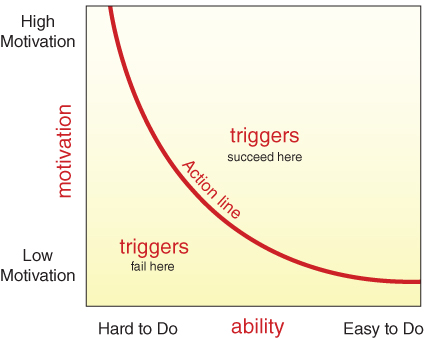

In essence, Fogg's Behavior Model says that three conditions are necessary to persuade you to take an action, such as making a purchase or clicking the “like” button:

- You must want to do it.

- You must be able to do it.

- You must be triggered to do it.

Fogg showed that triggers only work when people are already highly motivated (“I really need a new sweater!”) and when following through is easy (like the one-click checkout on Amazon). If the task is hard, you get frustrated and give up. Without sufficient motivation or ability, there's not enough force to carry you through the task if you meet resistance. And finally, there must be a stimulus.

Fogg had unintentionally found a surefire formula for keeping a user's eye on the ball: Offer them something they want, make it easy for them to get or use it, and continuously create triggers that keep them engaged.

The Fogg Behavior Model shows that three elements must converge at a given moment for a behavior to occur: Motivation, Ability, and Trigger. When a behavior does not occur, at least one of those three elements is missing.2

Reproduced with permission of Dr. B.J. Fogg.

Fogg himself added that the model “shows that motivation and ability can be traded off (e.g., if motivation is very high, ability can be low)” and that it “applies most directly to practical issues of designing for behavior change using today's technology.”3

Let's Take a Look at B.J. Fogg's Model as It Is Being Used Today…

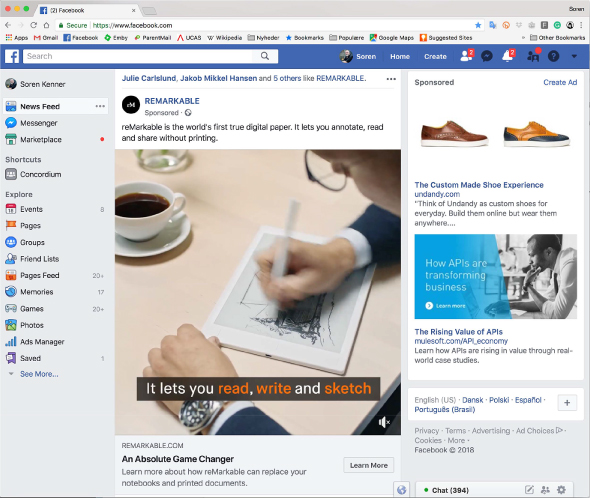

On the following page is a typical Facebook page (belonging to one of the authors). You can observe a lot of B.J. Fogg-based design here. It is also well worth remembering (we will get into this in more depth later) that when you browse on the web the different sites you visit set “cookies” on your PC or phone so they can recognize you and your interests later. Let's take a look at what we see on this Facebook page.

- The blue top bar shows a profile picture to remind the user that this page is “you” (you identify the page as part of “you”).

- The notification flags at the top provide a small dopamine reaction tempting me to discover who wants to friend me or what new notifications I have. These are “triggers,” or actions I am motivated to perform and know how to perform!

- The advertisement for shoes is a piece of “remarketing”—A cookie tracked my recent shoe purchase and is now remarketing shoes to me through a profiling setup. Although the tracker has discovered that I was looking for shoes, it has not figured out that I already bought shoes or perhaps the segmentation model used believes my propensity for buying more shoes will be higher now that I've bought the first pair.

- The so-called “sponsored content” ends up in my feed for the same reason as the shoes: I have been looking for a new tablet and this activity has been captured with a cookie. The targeting probably also reflects cookies that show I buy a lot of kindle books. And you can see that they have used the “friends like” feature that enables them to show names of my friends that have “liked” an ad for their product. This makes me more likely to click on the advert.

- The advert for “How APIs are transforming business” reflects that I have been researching software technology for a project I am involved in.

In other words, everything that is on this particular page is carefully targeted to one of your authors, based on what Facebook and the advertisers know about him and what sites he has visited in the past. Also worth noting is the language used by these adverts: “An Absolute Game Changer” is a hook designed to make you curious and pull you in. And yes, it may be a very fine tablet, but will it change the game? Doubtful. The tagline “The Custom-Made Shoe Experience” works a little better. It conveys the idea that you can pick up a pair of high-class custom-made shoes right here and now, which is a credible trigger, if you are motivated to buy new shoes. The advert for the API is the weakest of the bunch—its call to action is generic instead of specific and our guess would be that this particular ad did not perform well.

A couple of other observations: The notifications on the left side of the screen (pages feed, memories, games) are Fogg-based triggers designed to keep you investing time in Facebook instead of heading somewhere else. And so is one of the finest features and inventions of social media—“the infinity scroll”—with a high success rate for keeping you engaged long past your intended time allotment because you're now hypnotized by the screen unspooling endlessly like a road trip to nowhere. You just blow past a lot of posts, but others cause you to pause and read, perhaps even leaving a comment. In reality, you're being held captive by the same mechanism used in slot machines: you are browsing towards anticipation of reward (a payoff of three cherries, a post you would like to interact with). However, because the reward is dispensed unpredictably the dopamine keeps flowing and you remain engaged with the feed for a longer period of time. This design feature is also known as “stickiness” and is something every tech player in the business reveres and aims for as the pinnacle of efficient design.

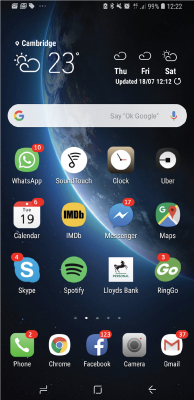

Your Phone Is a Slot Machine!

Here's a screenshot from Soren's Android phone (a Samsung Galaxy S8+ in case you were wondering). It's running an operating system called Android which is designed and owned by Google and it has the usual overload of applications that somehow made it onto the phone by persuading the owner they had something worthwhile to offer. At the last count there were about 100 applications installed on the phone—of which perhaps 15 are being used frequently.

The most obvious stickiness-hooks on the screenshot are the notifications with numbers that pop-up on top of the app-icon. These let the user know that “something” has happened, and you better come check it out (the sooner the better). Other common hooks are the icon designs (they are all colorful and attention grabbing) and the notification bar at the top of the screen where certain apps have gained access. On top of that there are all the lock-screen notifications (those messages that show up on your lock screen)—typically email headers, message headers and so on.

The original idea of notifications was a good one—to notify you of something that might need your attention. However, software developers soon realized that notifications were just another way of interacting with the user and could be designed to increase engagement. As soon as this became apparent, the notification wars began! Before long, every app ever created was clamoring for access to your “notification center” and for access to your screen.

As you know from the previous chapters of this book all of these notifications have an impact on you. They are directed at your “autopilot” or the “fast, impulsive layers” of your brain and they work exactly like waving a red cloth in front of a bull (actually bulls are colorblind, did you know?). They trigger an urge which, along with a small amount of dopamine, makes you want to find out what you are being notified of, in the hope of a “reward” (something that you feel good about engaging with). And because the system is set up so the rewards are unpredictable the pull becomes much stronger than if you knew exactly what you were getting when you click on the app.

The Pew Research Center in Washington has been tracking social media since 2012. In a 2018 report on social media use4 they conclude that roughly two-thirds of US adults are Facebook users and that about three-quarters of those users access Facebook daily.

Interestingly, 40 percent of surveyed users said they'd find it difficult to give up social media, compared to only 28 percent when asked the same question in 2014. Obviously, back then social media was not as much of a prerequisite for engaging socially—but by now social media has become a big enough part of enough people's lives that it becomes hard to give it up, not just because it is addictive, but also because when everyone else uses it as their primary form of communication, giving it up means giving up your ability (or at least limiting it) to communicate with your community.

Whatever the reason, it appears that social media sites' increased use of addictive design is working.

What Do the Companies Targeting You See?

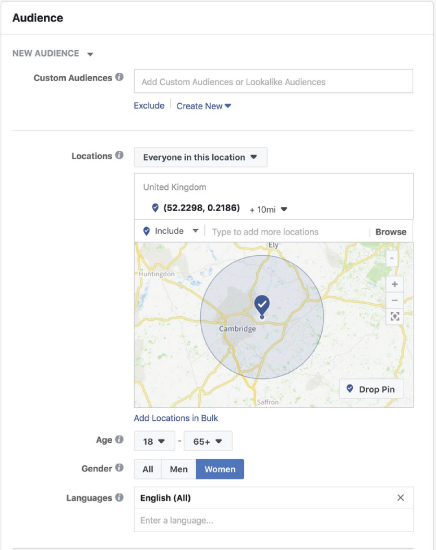

Facebook and many other social media platforms deliver interfaces designed to keep you stuck to their pages. They then open up for adverts that are designed to grab your attention and get you to visit the advertiser's website online store (or landing page). Let's take a look at the Facebook Ads manager store, where advertisers purchase potential customers' attention. Let's build a campaign for the book you are reading right now, just to show you the extent of detailed targeting that is available to advertisers.

Imagine entering a supermarket and looking at a map of the different aisles. As you can see, this campaign can be programmed to target a specific audience and to run at strategic times. It can also be optimized to deliver on a specific set of goals, such as building brand awareness, getting users to download and install apps, generating leads for future sales or getting users to visit your online store and shop.

Here are some examples of how granular you can get in your audience selection.

First off, we've selected Cambridge, UK, as our target and have narrowed our target audience to women between the ages of 18 and 65. We can narrow our target group even further by stipulating what sort of education we would like our targets to have and we can also sort our groups based on interests or behaviors such as going to concerts, eating Chinese food, or going on hikes.

These days, you can target people by pretty much anything, including whether or not you tend to shop online, what sort of mobile phone you use, whether or not you like pets, yoga, travel (and even what kind of travel). Users who've liked or interacted with other Facebook pages are also targeted—so if we find Facebook pages with lots of members and a theme that's in alignment with buying this book, we can target them directly.

But how on earth does Facebook know all this about you? Your interests, your education, your politics, your online behavior, your propensity for shopping? Simple: they collect and correlate every move you make on Facebook with that of other users. From an analytical standpoint you are part of a “cohort” with specific known traits. And if Facebook has solid knowledge that you fit four out of five data points in a given cohort the chances are good that you will fit the fifth as well. Is this way of generating profiling information on you perfect? No. But then again, it doesn't have to be. It just has to be good enough to allow the advertisers to reach you at a cost that still allows them to make money after their online marketing costs have been paid. All of this information about you is continuously collected by Facebook as you interact with it. These data profiles form the basis for the very accurate targeting that Facebook uses to sell about $50 billion-worth of adverts a year.

It's important to understand that in addition to being accurate, this profiling and targeting information is also flexible and continuously upgraded with new knowledge. Imagine that we posted an advert for this book, targeting 25 specific audience groups. Our first step, then, will likely be to monitor how those groups perform. Perhaps 15 of these groups like our offering and buy our book while the other 10 groups are less responsive. In this case, we obviously would quickly turn off the 10 unresponsive groups and instead create new groups based on audiences that look like the ones that are performing well (in Facebook parlance, this is known as “lookalike audiences”).

This is a very nifty feature and it assures that your adverts get better and better at reaching the right audience, allowing you to sell lots of books. Even better (and a little scary as well) this entire process is easy to automate so you can let software programs optimize the targeting of your adverts. And, as it turns out, this software usually ends up doing a better job at targeting potential buyers than we humans can.

Your Personality Can Be Predicted with Great Accuracy

Michal Kosinski is a Stanford assistant professor who holds a PhD in Psychology from the University of Cambridge. During his time at Cambridge he and Cambridge psychologist David Stillwell developed the “MYPERSONALITY PROJECT.” As we shall see, the idea was simple but the ramifications far-reaching.

Kosinski and his colleagues started out with a personality test based on the “Big 5” model of personality traits5 developed by J.M. Digman and Lewis Goldberg in 1990. In essence, the Big 5 model says that your personality can be described as a combination of five different traits: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism (also often known as OCEAN). The typical Big 5 survey consists of about 100 questions that are designed to get an idea of how open, conscientious, extrovert, agreeable and neurotic you are.6 The Big 5 model is widely used, and many studies have been undertaken to determine differences in personalities between men and women, between people hailing from different cultures or from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

But Kosinsky and Stillwell took Big 5 in an entirely different direction. First, they asked volunteers (of which there were hundreds of thousands) to take an online survey scoring their personality profile.7 They also asked the volunteers for access to their Facebook profile, so they could correlate the results of the personality study with the behavior (likes, postings, pictures, groups, etc.) of the volunteer on Facebook. Next, they started running calculations on all this data using some of the same cohort techniques described earlier in this chapter. Before long, the model was refined to where a mere peek at a Facebook profile would provide a very accurate assessment of the user's personality, interests, affiliations, gender, sexuality and so on.

In 2012, Kosinski demonstrated that access to just 68 likes of a user on Facebook would predict skin color (95% accuracy), sexual orientation (88% accuracy), democrat or republican (85% accuracy). And it didn't stop there—grinding away at the data it soon became clear that Facebook data would provide a very good idea about a person's intelligence, religious affiliation, alcohol and drug use or even whether someone's parents were divorced. Eventually Kosinski and his partners tuned their models to a level where access to a mere 70 likes would allow it to deduce more about you than your close friends know, 150 likes more than what your parents know about you, and 300 likes would give them more knowledge about you than your partner has.

The implications of this are more than a little bit sobering. By simply scanning your Facebook page and analyzing your pattern of likes, postings, photos and so forth, a piece of software can now predict your personality, your likes, your interests, your affinities and your behavior more accurately than your friends, your parents and even your life partner.

Scary? We think so. Interestingly, “on the day Kosinski published these findings he received two phone calls. One was the threat of a lawsuit and the other a job offer. Both were from Facebook.”8 Kosinski eventually completed his PhD and went on to become an assistant professor at Stanford but the ramifications of the work he had started would soon turn into a debacle of epic proportions involving whistleblowers, allegations of rigging the US presidential elections (as well as Brexit), hearings in the US Senate and much more.

The Cambridge Analytica Scandal

In 2013, a British behavioral research company called the SLC Group formed a new spinoff company called Cambridge Analytica. The company was partly owned by Robert Mercer, an American computer scientist, who was an early artificial intelligence developer. The purpose of Cambridge Analytica was to do political consulting based on data mining, data brokerage and data analysis.

As it would later turn out, Cambridge Analytica had somehow obtained data associated with more than 87 million Facebook profiles (maybe including yours, who knows?). How did this happen? Well, Kosinski's original survey was designed as a Facebook app that asked users for permission to access their entire network. The survey had 270 000 participants and by asking them for access to not only their own Facebook data but also the data of their friends, and friends of friends, Kosinski gained access to the data of 87 million Facebook users. Facebook has since closed this hole in their privacy management.

How Cambridge Analytica obtained this data is unclear.

However, once Cambridge Analytica had the key to these 87 million profiles they could start untangling an even bigger puzzle—in essence reverse-engineering the results of Kosinski by comparing what was known about this profiling data with other data that they could acquire from many different sources. Using many of the same techniques that Facebook uses to deliver “lookalike audiences” to advertisers, Cambridge Analytica set out to profile as large a portion of the US public as they possibly could—by their own claim, several hundred million people.

All of these profiles were entered into databases that were in turn used to design and drive communication approaches based on individual profiles. If Cambridge Analytica knew the issues occupying you or how you felt about them, then that was what they would write about as they kept focusing adverts and emails on you.

Many claims have been made that the Donald Trump campaign's use of Cambridge Analytica data to drive his campaign garnered him the presidential election. And as most will be aware, the aftermath of the revelation of how Cambridge Analytica misused 87 million Facebook profiles led to a senate hearing, to the bankruptcy of Cambridge Analytica, and to Facebook implementing new and much more strict privacy policies.

Did Cambridge Analytica in fact help Donald Trump win the election?

The authors of this book doubt it. As we shall see a little further down the road, profiling data is extremely handy when it comes to targeting customers and selling them goods and services, but it turns out that getting people to change their values and politics is much harder.

Either way, what we can learn from Kosinski's work on profiling is that once you have enough data on a fairly large group of people, then only very little data is needed to take a very good guess at how a given consumer will behave when presented with an offering, whether it's a product, a service or a group affiliation. And as you will soon see, that insight is being relentlessly used against you by both Facebook and Google, and the advertisers they service.

How You Are Captured and Converted

Obviously, for the thousands of marketers that use the major internet platforms to sell their goods and services, this is just the head of the trail. In order to sell to you, a few more things have to happen, and a lot of it is predicated on B.J. Fogg.

First, advertisers need to entice you temporarily away from Facebook (or Google) and get you into their own domain or shop. Making this work basically consists of several steps: displaying something that piques your interest and makes you click; providing a landing page for your click (the page you are directed to when you click on an advert) that is appealing, and which makes it easy for you to want to part ways with some of your money in return for whatever it is the vendor is selling.

Predictably, enticing you to learn more about a product or service by presenting it as efficiently as possible (from the advertisers' point of view) has given birth to an industry of its own. The picture on the next page is a screen grab from an online marketing platform called “Unbounce”—a company that specializes in templates for advertisers to build efficient landing pages that generate lots of sales. As you can see, Unbounce is brutally honest about its use of addictive design in their landing page templates. The goal: “drive more leads and revenue from any web page by showing targeted popups and sticky bars to specific users.” Unbounce is in no way unique—there are many other companies out there supplying the same sort of service.

In essence, Unbounce helps its customers (advertisers) systemize and optimize their management of your attention. The graphic above describes the process and tools they offer. Behind the Unbounce template is a process and workflow that makes it easier for advertisers to build and test landing pages you can't resist clicking on. Your click converts your interest into sales by a number of mechanisms, including on-screen chatting, emails, remarketing if the sale fails, and a host of other functions. It's all completely automated, and because the software learns by doing, it constantly improves its ability to lasso you with attention-grabbing offers you can't refuse.

At this point you are probably beginning to get a sense of just how efficient the digital manipulation you are being exposed to is. If you find this worrying, just wait till you see just how deep this rabbit hole goes …

Multivariate Testing—Helping Consumers Capture Themselves

Let's assume for a moment—purely theoretical of course—that we have a really interesting book about the side effects of smartphones and social media we want to sell to you. We understand how we can use Facebook or Google to get your attention at a reasonable cost, and we know how to get you to click on an advert generated by one of these services. We also have a pretty good idea of who our core audience might be. But once a potential customer clicks on an advert and ends up on our landing page, marketers still must find the right message and the right look to maximize sales.

In the last century, advertising agencies hired copywriters and art directors to knock together adverts that they thought would have impact. In the early days, they worked on intuition and observation, and because they were experienced professionals they often got it right—but not as right as software can today.

Say hello to “multivariate testing,”9 a very powerful way of letting consumers decide what works best for them. The basic idea is simple. Let's assume you want to build a landing page that sells this theoretical book really well. This landing page will typically consist of a number of elements: a headline, a couple of paragraphs about the book, a picture of the book, perhaps a picture of the authors, endorsements from readers, and so on. Nothing unusual about the recipe—if you buy and read books you have probably already seen some version of it a thousand times.

But imagine that you started out by deciding to test different ways of constructing your landing page in order to find the best-selling one. Let's say you create 10 headlines, 10 different descriptions of the book, 10 different photos, 10 different “calls to actions” and 10 different ways of organizing endorsements, plus you decide to do the layout of all this in 10 different designs (headline at the top, headline under the photo of the book, etc.).

This would be an interesting experiment if not for the fact that you would need to design and test 600 000 landing pages to find out which one was best.

Here's where multivariate testing comes into the picture—via a piece of software it automatically generates landing pages that matches your requirements—and it does not need to run tests on 600 000 pages to tell you which landing pages perform best—thanks to a very smart algorithm that manages to break your possible variates into a number of cells that are then optimized by analysis of how clicks (customers) respond to each cell. The best performing software in this category would only need about 5000 clicks to tell you with 99.9% accuracy which of your 600 000 test pages sell the most books!

And obviously once advertisers harness the power of user-testing on their landing page design (or in their online shop or anywhere else) they realize that the same approach can also be used to divide up audiences and sell more because they can target better and more precisely. This way advertisers can (and do) test their way to realizing that swimwear landing pages with pictures of bikinis sell better in California while one-piece swimwear sells better in the Midwest.

As you are probably beginning to realize, the adverts you see on your screen are designed to target you personally. When you click on them, the pages you reach have most likely been tested extensively and are predictive of your desires. But wait—there's more!

The Strange World of Tracking Pixels, Cookies and Remarketing

There are many different ways websites (such as Facebook and Google or advertiser sites such as Walmart or eBay) can keep track of your comings and goings. This is regardless of whether you access these sites via a smartphone, a tablet or a nice old-fashioned iMac (like the one this book was written on). As you browse the Internet many of the sites you visit leave “cookies” on your device—small files that collect data. Some of these cookies are “tracking cookies” (sometimes also known as third-party cookies) and as the name implies, these cookies track your browsing and they can be read by many different advertisers. These cookies send a log of your online activities to a remote database for analysis. Some cookies only collect and send anonymous information while others actually collect and send specific user information that can include names and addresses to the tracker host.

If you have been browsing online shops, social media and news sites for just a little while and stop to take a look at what your browser has picked up, you should not be surprised to discover several hundreds of these cookies stored in your browser and waiting to track your daily little burst of news, social media and/or dopamine. All of this data (and it is a lot) is collected and used by advertisers in a number of ways—ways that are becoming increasingly more sophisticated. When an advert is about to be loaded to a page you are browsing, the host serving the adverts (this is just another piece of automated software) looks for cookies on your browser it can use to determine what adverts to show and can also send a record of your visit to the advertiser in order to make it possible to target you even more precisely at your next visit. Some ads will even address you by name and mention your location.

The illustration on the previous page is the homepage of a “retargeting” company called Shoelace. Their software enables advertisers to put a stream of adverts in front of you based on what they know about you (information collected via cookies, tracking pixels, IP addresses, and more). So let's say you have been spending some time on Facebook. And you got tracked browsing a group that sells books. Let's further assume I have 10 different books I would like to sell to you.

Shoelace makes it possible to show you my books on other pages you visit—and since I don't want to wear your attention out by showing you the same book over and over again (because that would lead to a lack of interest), I can keep trying to throw different titles at you to see what piques your interest. What's more, Shoelace is smart—it learns from experience. As it keeps track of how you respond, there's a snowball effect and its algorithms get to know you better and better. And that leads to ever more potent advertising.

So, in essence, you are being targeted with adverts based on deep knowledge of your interests, browsing habits, purchasing habits and so forth. And because of the continuous testing and optimization of approaches, content and design used by advertisers they get better and better at hitting their mark. Mind you—not everyone that clicks on a landing page buys a product or service and for most marketers a conversion rate (the percentage of clicks that convert to sales) of around 1–3% is just fine and more than enough to pay for the clicks that did not convert as well as leave a tidy profit.

From the advertiser's perspective this all makes sense. Of course, they're maximizing their advertising dollars. But from your perspective as a consumer, you are part of a precarious balance and you may not like your place in this ecosystem if you see what's really happening. It goes like this: The titans offering the eyeballs (Google, Facebook, etc.) are looking to make as much revenue as they can by keeping your attention riveted. The advertisers would like to purchase your attention as cheaply as possible in order for them to make more money. You are caught in the middle. As long as Google and Facebook can continue to grow their audiences, the balance between the need for revenue growth and delivering a good user experience can be met. At some point, however, when all of the users have been onboarded and the advertisers are paying as much as they can afford to pay while still being able to make money, then what?

It's hard to tell exactly how that dilemma will play out but given the fact that nearly half the world's population is already using these services (and by far the majority of citizens in the countries with the most developed economies) there is little doubt that the “showdown in Techistan” will be taking place sooner rather than later.10

All Aboard the Consumer Journey Train

If you are an entertainment provider, an e-retailer, an online bookshop or any other sort of potential advertiser, the latest trend in online marketing is the construction of complete customer journeys. Think of it as a complete set of rails laid out in front of you and designed to keep you engaged by exposing you to a number of different approaches.

Goal number one is getting you from Facebook or YouTube or Google to a landing page. But what happens if you do not respond to the offer on the landing page? Then there has to be some other trigger that can move you to the online store and get you browsing there.

Let's say you find something you like, and you put it in your “shopping cart.” Let's back up for a sec—of course we mean your online shopping cart, which is a very different breed of cat than the cart you push around at the grocery. Just imagine, for example, that your shopping cart at Whole Foods prompted you to take certain actions without you even realizing it. That's what your online shopping cart is designed for! Just look at what happens if you go to checkout and then have second thoughts. You decide not to purchase that fake fur chinchilla hat after all and leave the site. Needless to say, that's anathema to all stations in this chain of commerce. That's “shopping cart abandonment” and that simply won't do. Luckily for the advertiser, his intelligent customer journey software (often also known as a marketing automation solution) takes care of things. It shoots off a quick email to let you know that it thinks you should come back and complete your purchase. And at the same time it waits and sees if it can catch you somewhere else—oh, hey, there you are browsing an article on a news site—and immediately delivers an advert or even better a “pop-up” window to that site informing you that your shopping cart is still there waiting for your purchase—with a 10 percent rebate but only if you act now!

You're probably starting to see that almost nothing you see online is random, generic or the same for everyone. It is high-precision marketing with a high definition scope that has you in its crosshairs and will plant its message literally inside the base of your skull, using numerous highly sophisticated ploys extracted from psychology and behavioral science.

The Horrible Dark Patterns

On top of all the tracking, the segmentation modeling, the testing, the retargeting and the “customer journeys” there are also a number of ploys that are even more insidious. Here are just a few of them—chances are you have seen many of them before but may not have reflected on what they are designed to do. If you go to the website darkpatterns.org you will get a lot more detail and examples of some of these approaches:

- Disguised Ads: Adverts disguised as other kinds of content or navigation, in order to get you to click on them.

- Confirm Shaming: Guilting users into opting into something. The option to decline is worded in such a way as to shame the user into compliance.

- Forced Continuity: When your free trial with a service comes to an end your credit card is charged without any warning.

- Hidden Costs: At the last step of the checkout process you discover that unexpected charges have appeared, e.g. delivery charges, tax, etc.

- Price Comparison Prevention: The advertiser makes it hard to compare the price of an item with another item, so you cannot make an informed decision.

- Privacy Zuckering: Being tricked into publicly sharing more information about yourself than you really intended to. Aptly named after Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

- Roach Motel: Design that makes it easy for you to get in but difficult to opt-out. Test: See if you can find the button that deactivates your Amazon account in less than 10 minutes, we dare you.

- Sneak into Basket: Somewhere during your purchasing journey the site sneaks an additional item into your basket, often through the use of an opt-out radio button or checkbox on a prior page.

How Google Skews Your Search Results

If you are like most of us, Google is your “go-to” resource when it comes to searching of any kind. But did you know that the search results Google delivers are not generic but rather personalized to you and skewed by Google to fit their idea of what you would like to see?

There is not necessarily anything wrong with Google using the information they have on you to provide search results they think you would like—but there is a very real danger that it promotes “confirmation bias” in your engagement with the online world, causing you to believe fake news, rely on unreliable news sources and ultimately develop a distorted view of reality—if you don't look out. More on this later.

Let's take a look at some of the methods Google uses to personalize your search results.11 Let's say you search for “coffee shop” —Google will consider the following when determining what search results to send back to you:

- Location (captured by IP-number or the GPS in your phone).

- Previous search and browsing history (where you have been).

- Stored social media profile (what your friends have to say).

- The device you are using (are you on the go or stationary).

- Other Google Products you use—for adding later personalization.

Based on these and a number of other and more esoteric factors, the Google Search Engine Ranking Algorithm whips up your personalized search results (and in fact does so 40 000 times per second or a staggering 3.5 billion times a day).

Now this is all good and fine when it helps Google help you find a coffee shop that serves extra hot soy milk (no fat), caffeine-free (skinny) cafe latte. But how about when you are searching to find news of the world around you? How do you feel about getting plugged into news sources, based not on a generalization but on specific profiling of you as a person? Or what about if you use Google to research an ethical dilemma, or the pros and cons of a particular political position? Are you still happy to have search results delivered based on profiling?

And obviously personalized search is not the only area where Google is skewing its search results. As many will be aware, the EU recently fined Google $2.7 billion12 for skewing search results for shoppers to favor outlets that Google has an interest in or have received advertising revenue from.

Google has appealed the fine, claiming no wrongdoing: “While some comparison-shopping sites naturally want Google to show them more prominently, our data shows that people usually prefer links that take them directly to the products they want, not to websites where they have to repeat their searches,” according to Kent Walker, Google SVP and general counsel.

However, a 2015 study undertaken by Harvard Business School professor Michael Luca and Columbia Law School professor Tim Wu finds that Google does indeed skew results. In their preamble, they say that “by prominently displaying Google content in response to search queries, Google is able to use its dominance in search to gain customers for this content. This may reduce consumer welfare if the internal content is inferior to organic search results.”13

So, to recap—now you know just how much the tech industry and advertisers know about you and you have seen some of the techniques they use to keep you riveted to their services. In the next chapter we will take a look at what all this hoopla does to your cognitive apparatus.