chapter at a glance

When we're feeling good there's hardly anything better. But when we're feeling down, it takes a toll on us and possibly others. OB scholars are very interested in emotions, attitudes, and job satisfaction. Here's what to look for in Chapter 3. Don't forget to check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

WHAT ARE EMOTIONS AND MOODS?

Emotions

Emotional Intelligence

Types of Emotions

Moods

HOW DO EMOTIONS AND MOODS INFLUENCE BEHAVIOR IN ORGANIZATIONS?

Emotion and Mood Contagion

Emotional Labor

Emotions and Moods across Cultures

Emotions and Moods as Affective Events

Functions of Emotions and Moods

WHAT ARE ATTITUDES?

Components of Attitudes

Attitudes and Behavior

Attitudes and Cognitive Consistency

Types of Job Attitudes

WHAT IS JOB SATISFACTION AND WHAT ARE ITS IMPLICATIONS?

Components of Job Satisfaction

Job Satisfaction Findings

Job Satisfaction and Behavior

Job Satisfaction and Performance

Some call Don Thompson, president of McDonald's USA, the accidental executive. At the age of 44 he's not only one of the youngest top managers in the Fortune 500, he also may have followed the most unusual career path. After graduating from Purdue with a degree in electrical engineering, Johnson went to work for Northrop Grumman. He did well, rose into management, and one day received a call from a head-hunter. Thompson listened, thinking the job being offered was at McDonnell Douglas Company—another engineering centric firm. After finding out it was at McDonald's he almost turned the opportunity down. But with encouragement he took the interview, and his career and McDonald's haven't been the same since.

Thompson hit the ground running at McDonald's and did well. But he became frustrated at one point after failing to win the annual President's award. He decided it might be time to move on. The firm's diversity officer recommended he speak with Raymond Mines, at the time the firm's highest-ranking African-American executive. When Thompson confided that he "wanted to have an impact on decisions," Mines told him to move out of engineering and into the operations side of the business. Thompson did and his work excelled. It got him the attention he needed to advance to ever-higher responsibilities that spanned restaurant operations, franchisee relations, and strategic management.

Don Thompson, president of McDonald's USA, is described as having "the ability to listen, blend in, analyze and communicate."

The president's office at McDonald's world headquarters in Oak Brook, Illinois has no door; the building is configured with an open floor plan. And that fits well with Thompson's management style and personality. His former mentor Raymond Mines says: "he has the ability to listen, blend in, analyze and communicate. People feel at ease with him. A lot of corporate executives have little time for those below them. Don makes everyone a part of the process." As for Thompson, he says "I want to make sure others achieve their goals, just as I have."

feelings do make a difference

How do you feel when you are driving a car and halted by a police officer? You are in class and find out you received a poor grade on an exam? A favorite pet passes away? You check your e-mail and discover that you are being offered a job interview? A good friend walks right by without speaking? A parent or sibling or child loses their job? Or, you get this SMS from a new acquaintance: "Ur gr8

These examples show how what happens to us draws out "feelings" of many forms, such as happy or sad, angry or pleased. These feelings constitute what scholars call affect, the range of feelings in the forms of emotions and moods that people experience in their life context.[193] Affects have important implications not only for our lives in general but also our behavior at work.[194] Don Johnson, featured in the opening example, might have allowed his "frustration" at slow career progress to turn into negative affect toward McDonald's. Fortunately for him and the company it didn't. With the help of a career mentor, his willingness to work hard was supported by positive affects that surely contributed to his rise to senior management.

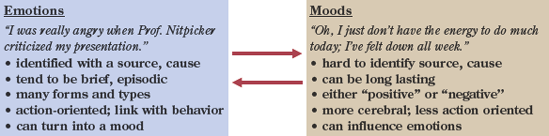

Anger, excitement, apprehension, attraction, sadness, elation, grief ... An emotion is a strong positive or negative feeling directed toward someone or something.[195] Emotions are usually intense, not long-lasting, and always associated with a source—someone or something that makes us feel the way we do. For example, you might feel positive emotion of elation when an instructor congratulates you on a fine class presentation; you might feel negative emotion of anger when an instructor criticizes you in front of the class. In both situations the object of your emotion is the instructor, but the impact of the instructor's behavior on your feelings is quite different in each case. And your behavior in response to the aroused emotions is likely to differ as well—perhaps breaking into a wide smile after the compliment, or making a nasty side comment or withdrawing from further participation after the criticism.

Emotions are strong positive or negative feelings directed toward someone or something.

All of us are familiar with the notions of cognitive ability and intelligence, or IQ, which have been measured for many years. A more recent concept is emotional intelligence, or EI. First introduced in Chapter 1 as a component of a manager's essential human skills, it is defined by scholar Daniel Goleman as an ability to understand emotions in ourselves and others and to use that understanding to manage relationships effectively.[196] EI is demonstrated in the ways in which we deal with affect, for example, by knowing when a negative emotion is about to cause problems and being able to control that emotion so that it doesn't become disruptive.

Goleman's point with the concept of emotional intelligence is that we perform better when we are good at recognizing and dealing with emotions in ourselves and others. When we are high in EI, we are more likely to behave in ways that avoid having our emotions "get the better of us." Knowing that an instructor's criticism causes us to feel anger, for example, we might be better able to control that anger when being criticized, maintain a positive face, and perhaps earn the instructor's praise when we make future class contributions. If the unchecked anger caused us to act in a verbally aggressive way—creating a negative impression in the instructor's eyes—or to withdraw from all class participation—causing the instructor to believe we have no interest in the course, our course experience would likely suffer.

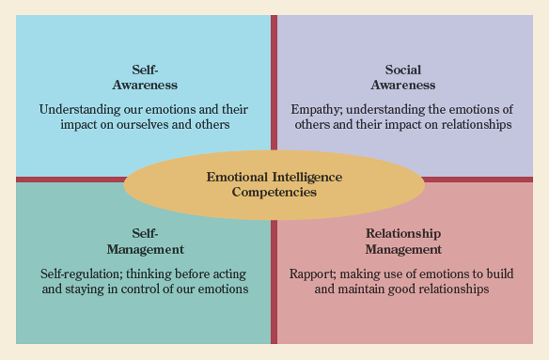

The essential argument is that if you are good at knowing and managing your emotions and are good at reading others' emotions, you may perform better while interacting with other people. This applies to work and life in general, and to leadership situations in particular.[197] Figure 3.1 identifies four essential emotional intelligence competencies that can and should be developed for leadership success and, we can say, success more generally in all types of interpersonal situations.[198] The competencies are self-awareness, social awareness, self-management, and relationship management.

Self-awareness is the ability to understand our emotions and their impact on our work and on others. You can think of this as a continuing appraisal of your emotions that results in a good understanding of them and the capacity to express them naturally. Social awareness is the ability to empathize, to understand the emotions of others, and to use this understanding to better relate to them. It involves continuous appraisal and recognition of others' emotions, resulting in better perception and understanding of them.

Self-management in emotional intelligence is the ability to think before acting and to be in control of otherwise disruptive impulses. It is a form of self-regulation in which we stay in control of our emotions and avoid letting them take over. Relationship management is an ability to establish rapport with others in ways that build good relationships and influence their emotions in positive ways. It shows up as the capacity to make good use of emotions by directing them toward constructive activities and improved relationships.

Self-awareness is the ability to understand our emotions and their impact on us and others.

Social awareness is the ability to empathize and understand the emotions of others.

Self-management is the ability to think before acting and control disruptive impulses.

Relationship management is the ability to establish rapport with others to build good relationships.

When it comes to emotions and emotional intelligence, researchers have identified six major types of emotions: anger, fear, joy, love, sadness, and surprise. The key question from an emotional intelligence perspective is: Do we recognize these emotions in ourselves and others, and can we manage them well? Anger, for example, may involve disgust and envy, both of which can have very negative consequences. Fear may contain alarm and anxiety; joy may contain cheerfulness and contentment; love may contain affection, longing, and lust; sadness may contain disappointment, neglect, and shame.

It is also common to differentiate between self-conscious emotions that arise from internal sources and social emotions that are stimulated by external sources.[199] Shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride are examples of internal emotions. Understanding self-conscious emotions helps individuals regulate their relationships with others. Social emotions like pity, envy, and jealousy derive from external cues and information. An example is feeling envious or jealous upon learning that a co-worker received a promotion or job assignment that you were hoping to get.

Whereas emotions tend to be short-term and clearly targeted at someone or something, moods are more generalized positive and negative feelings or states of mind that may persist for some time. Everyone seems to have occasional moods, and we each know the full range of possibilities they represent. How often do you wake up in the morning and feel excited and refreshed and just happy, or wake up feeling grouchy and depressed and generally unhappy? And what are the consequences of these different moods for your behavior with friends and family, and at work or school?

Moods are generalized positive and negative feelings or states of mind.

In respect to OB a key question relating to moods is how do they affect someone's likeability and performance at work? When it comes to CEOs, for example, a Business Week article claims that it pays to be likable; "harsh is out, caring is in."[200] Some CEOs are even hiring executive coaches to help them manage their affects to come across as more personable and friendly in relationships with others. If a CEO goes to a meeting in a good mood and gets described as "cheerful," "charming," "humorous," "friendly," and "candid," she or he may be viewed as on the upswing. But if the CEO goes into a meeting in a bad mood and is perceived as "prickly," "impatient," "remote," "tough," "acrimonious," or even "ruthless," the view will more likely be of a CEO on the downslide.

Figure 3.2 offers a brief comparison of emotions and moods. In general, emotions are intense feelings directed at someone or something; they always have rather specific triggers; and they come in many types—anger, fear, happiness, and the like. Moods tend to be more generalized positive or negative feelings. They are less intense than emotions and most often seem to lack a clear source; it's often hard to identify how or why we end up in a particular mood.[201] But moods tend to be more long-lasting than emotions. When someone says or does something that causes a quick and intense positive or negative reaction from you, that emotion will probably quickly pass. However, a bad or good mood is likely to linger for hours or even days, is generally displayed in a wide range of behaviors, and is less likely to be linked with a specific person or event.

Not too long ago, CEO Mark V. Hurd of Hewlett-Packard found himself dealing with a corporate scandal. It seems that the firm had hired "consultants" to track down what were considered to be confidential leaks by members of HP's Board of Directors. When meeting the press and trying to explain the situation and resignation of Board Chair Patricia C. Dunn, Hurd called the actions "very disturbing" and The Wall Street Journal described him as speaking with "his voice shaking."[202]

Looking back on this situation, we can say that Hurd was emotional and angry that the incident was causing public humiliation for him and the company. Chances are the whole episode resulted in him being in a bad mood for a while. In the end both he and the company came out of the scandal fine, but in the short run, at least, Hurd's emotions and mood probably had consequences for those working directly with him and for HP's workforce as a whole.

Although emotions and moods are influenced by different events and situations, each of us may be prone to displaying some relatively stable tendencies.[203] Some people seem most always positive and upbeat about things. For these optimists we might say the glass is nearly always half full. Others, by contrast, seem to be often negative or downbeat. They tend to be pessimists viewing the glass as half empty. Such tendencies toward optimism and pessimism not only influence the individual's behavior, they can also influence other people he or she interacts with—co-workers, friends, and family members.

Researchers are increasingly interested in emotion and mood contagion—the spillover effects of one's emotions and mood onto others.[204] You might think of emotion and mood contagion as a bit like catching a cold from someone. Evidence shows that positive and negative emotions are "contagious" in much the same ways, even though the tendency may be underrecognized in work settings. In one study team members were found to share good and bad moods within two hours of being together; bad moods, interestingly, traveled person-to-person faster than good moods.[205] Other research found that when mood contagion is positive followers report being more attracted to their leaders and rate the leaders more highly. Mood contagion can also have inflationary and deflationary effects on the moods of co-workers and teammates, as well as family and friends.[206]

Daniel Goleman and his colleagues studying emotional intelligence consider emotion and mood contagion an important leadership issue that should be managed with care. "Moods that start at the top tend to move the fastest," they say, "because everyone watches the boss."[207] This was very evident as CEOs in all industries—business and nonprofit alike, struggled to deal with the impact of economic crisis on their organizations and workforces. "Moaning is not a management task," said Rupert Stadler of Audi: "We can all join in the moaning, or we can make a virtue of the plight. I am rather doing the latter."[208]

The concept of emotional labor relates to the need to show certain emotions in order to do a job well. It is a form of self-regulation to display organizationally desired emotions in one's job. Good examples come from service settings such as airline check-in personnel or flight attendants. They are supposed to appear approachable, receptive, and friendly while taking care of the things you require as a customer. Some airlines like Southwest go even further in asking service employees to be "funny" and "caring" and "cheerful" while doing their jobs.

Emotional labor isn't always easy; it can be hard to be consistently "on," projecting the desired emotions associated with one's work. If you're having a bad mood day or just experienced an emotional run-in with a neighbor, for example, being "happy" and "helpful" with a demanding customer might seem a little much to ask. Such situations can cause emotional dissonance where the emotions we actually feel are inconsistent with the emotions we try to project.[210] That is, we are expected to act with one emotion while we actually feel quite another.

Using the service setting as an example again, imagine how often service workers struggling with personal emotions and moods experience dissonance when having to display very different ones toward customers.[211] Scholars point out that deep acting occurs when someone tries to modify their feelings to better fit the situation—such as putting yourself in the position of the air travelers whose luggage went missing and feeling the same sense of loss. Surface acting is a case of hiding true feelings while displaying very different ones—such as smiling at a customer even though they just offended you.

Issues of emotional intelligence, emotion and mood contagion, and emotional labor, become even more complicated in cross-cultural situations. The frequency and intensity of emotions has been shown to vary among cultures. In mainland China, for example, research suggests that people report fewer positive and negative emotions as well as less intense emotions than in other cultures.[212] Yet people's interpretations of emotions and moods appear similar across cultures, with the major emotions of happiness, joy, and love all valued positively.[213]

Norms for emotional expression can vary across cultures. In collectivist cultures that emphasize group relationships, individual emotional displays are less likely to occur and less likely to be accepted than in individualistic cultures.[214] Informal cultural standards called display rules govern the degree to which it is appropriate to display emotions. For example, British culture tends to encourage downplaying emotions, while Mexican culture is much more demonstrative in public. When Wal-Mart first went to Germany, its executives found that an emphasis on friendliness embedded in its U.S. Roots, didn't work as well in the local culture. The more "serious" German shoppers did not respond well to Wal-Mart's friendly greeters and helpful personnel. And along the same lines, Israeli shoppers equate smiling cashiers with inexperience; cashiers are encouraged to look somber while performing their jobs.[215] Overall, the lesson is that we should be sensitive to the way emotions are displayed in other cultures; often they may not mean what they do at home.

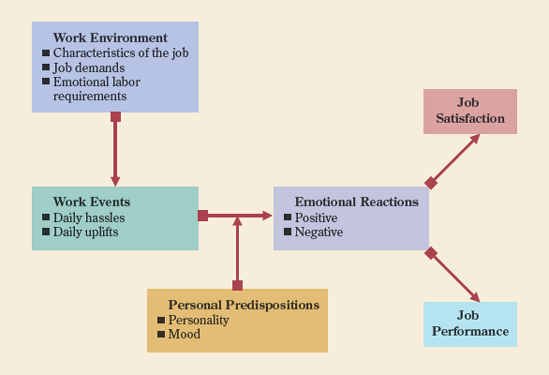

Figure 3.3 summarizes the Affective Events Theory as a way of summarizing and integrating this discussion of emotions, moods, and human behavior in organizations.[216] The basic notion of the theory is that our emotions and moods are influenced by events involving other people and situations, and these emotions and moods, in turn, influence the work performance and satisfaction of us and others.

The left-hand side of Figure 3.3 indicates how the work environment, including emotional labor requirements, and work events like hassles and uplifts create emotional reactions. These, in turn, influence satisfaction and performance.[217]

We have all experienced hassles and uplifts on the job, sometimes many of these during a work day. People respond to these experiences through positive and negative emotional reactions. Personality may influence positive and negative reactions, as can moods. Your mood at a given time can exaggerate the nature of the emotions you experience as a result of an event. For example, if you have just been laid off, you are likely to feel worse than you would otherwise when a colleague says something to you that was meant as a neutral comment.

In the final analysis, we should remember that emotions and moods can be functional as well as dysfunctional. The important thing is to manage them well—the essence of emotional intelligence. Emotions and moods communicate; they are messages to us that can be valuable if heard and understood.[218] Some, such as Charles Darwin, have argued that emotions are useful in a person's survival process. For instance, the emotion of excitement may encourage you to deal with situations requiring high levels of energy, such as special school and job assignments. Although the emotion of anger is often bad, when channeled correctly it might stop someone from taking advantage of you.

At one time Challis M. Lowe was one of only two African-American women among the five highest-paid executives in U.S. companies surveyed by the woman's advocacy and research organization Catalyst.[219] She became executive vice president at Ryder System after a 25-year career that included several changes of employers and lots of stressors—working-mother guilt, a failed marriage, gender bias on the job, and an MBA degree earned part-time. Through it all she says: "I've never let being scared stop me from doing something. Just because you haven't done it before doesn't mean you shouldn't try." That, simply put, is what we would call a can-do "attitude!"

An attitude is a predisposition to respond in a positive or negative way to someone or something in one's environment. For example, when you say that you "like" or "dislike" someone or something, you are expressing an attitude. It's important to remember that an attitude, like a value, is a hypothetical construct; that is, one never sees, touches, or actually isolates an attitude. Rather, attitudes are inferred from the things people say or through their behavior. They are influenced by values and are acquired from the same sources—friends, teachers, parents, role models, and culture. But attitudes focus on specific people or objects. The notion that shareholders should have a voice in setting CEO pay is a value; your positive or negative feeling about a specific company due to the presence or absence of shareholder inputs on CEO pay is an attitude toward it.

An attitude is a predisposition to respond positively or negatively to someone or something.

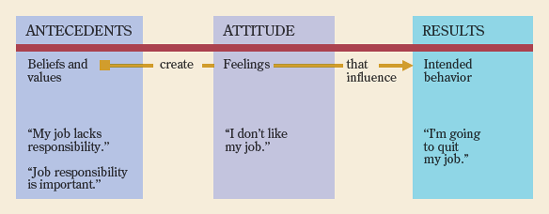

The three basic components of an attitude are shown in Figure 3.4—cognitive, affective, and behavioral.[220] The cognitive component of an attitude reflects underlying beliefs, opinions, knowledge, or information a person possesses. It represents a person's ideas about someone or something and the conclusions drawn about them. The statement "My job lacks responsibility" is a belief shown in the figure. The statement "Job responsibility is important to me" reflects an underlying value. Together they comprise the cognitive component of an attitude toward one's work or workplace.

The affective component of an attitude is a specific feeling regarding the personal impact of the antecedent conditions evidenced in the cognitive component. In essence this becomes the actual attitude, such as the feeling "I don't like my job." Notice that the affect in this statement displays the negative attitude; "I don't like my job" is a very different condition than "I do like my job."

The behavioral component is an intention to behave in a certain way based on the affect in one's attitude. It is a predisposition to act, but one that may or may not be implemented. The example in the figure shows behavioral intent expressed as "I'm going to quit my job." Yet even with such intent, whether or not the person really quits is quite another story indeed.

As just discussed, the link between attitudes and behavior is tentative. An attitude expresses an intended behavior that may or may not be carried out. In general we can say that the more specific attitudes are, the stronger the relationship with eventual behavior. A person who feels "I don't like my job" may be less likely to actually quit than someone who feels "I can't stand another day with Alex harassing me at work." It's also necessary to have the opportunity or freedom to behave in the intended way. In today's recessionary economy there are most likely many persons who stick with their jobs while still holding negative job attitudes. The fact is they may not have any other choice.[221]

An important issue in the attitude-behavior linkage is consistency. Leon Festinger, a noted social psychologist, uses the term cognitive dissonance to describe a state of inconsistency between an individual's attitudes and/or between attitudes and behavior.[222] Let's assume that you have the attitude that recycling is good for the economy; you also realize you aren't always recycling everything you can while traveling on vacation. Festinger points out that such cognitive inconsistency is uncomfortable and results in attempts to reduce or eliminate the dissonance. This can be done in one of three ways: (1) changing the underlying attitude, (2) changing future behavior, or (3) developing new ways of explaining or rationalizing the inconsistency.

The way we respond to cognitive dissonance is influenced by the degree of control we seem to have over the situation and the rewards involved. In the case of recycling dissonance, for example, the lack of convenient recycling containers would make rationalizing easier and changing the positive attitude less likely. A reaffirmation of intention to recycle in the future can also reduce the dissonance.

Even though attitudes do not always predict behavior, the link between attitudes and potential or intended behavior is important for managers to understand. Think about your work experiences or conversations with other people about their work. It isn't uncommon to hear concerns expressed about someone's "bad attitude" or another's "good attitude." Such attitudes appear in different forms, including job satisfaction, job involvement, organizational commitment, and employee engagement.

You often hear the term "morale" used when describing the feelings of a is the workforce toward their employer. It relates to the more specific notion of job satisfaction, an attitude reflecting a person's positive and negative feelings toward a job, co-workers, and the work environment. Indeed, you should remember that helping others achieve job satisfaction is considered as a key result that effective managers accomplish. That is, they create a work environment in which people achieve both high performance and high job satisfaction. This concept of job satisfaction is very important in OB and receives special attention in the following section.

Job satisfaction is the degree to which an individual feels positive or negative about a job.

In addition to job satisfaction there are other attitudes that OB scholars and researchers study and measure. One is job involvement, which is defined as the extent to which an individual is dedicated to a job. Someone with high job involvement psychologically identifies with her or his job, and, for example, would be expected to work beyond expectations to complete a special project.

Another work attitude is organizational commitment, or the degree of loyalty an individual feels toward the organization. Individuals with a high organizational commitment identify strongly with the organization and take pride in considering themselves members. Researchers recognize two primary dimensions to organizational commitment. Rational commitment reflects feelings that the job serves one's financial, developmental, professional interests. Emotional commitment reflects feelings that what one does is important, valuable, and of real benefit to others. Evidence is that strong emotional commitments to the organization, based on values and interests of others, are as much as four times more powerful in positively influencing performance than are rational commitments, based primarily on pay and self-interests.[223]

A survey of 55,000 American workers by the Gallup Organization suggests that profits for employers rise when workers' attitudes reflect high job involvement and organizational commitment. This combination creates a high sense of employee engagement—a positive work attitude that Gallup defines as working with "passion" and feeling "a profound connection" with one's employer.[224] Active employee engagement shows up as a willingness to help others, to always try to do something extra to improve performance, and to speak positively about the organization. Things that counted most toward high engagement in the Gallup research were believing one has the opportunity to do one's best every day, believing one's opinions count, believing fellow workers are committed to quality, and believing there is a direct connection between one's work and the company's mission.[225]

There is no doubt that one of the most talked about of all job attitudes is job satisfaction, defined earlier as an attitude reflecting a person's evaluation of his or her job or job experiences at a particular point in time.[226] And when it comes to job satisfaction there are several good questions that we should answer. What are the major components of job satisfaction? What are the main job satisfaction findings? What is the relationship between job satisfaction and job performance?

Managers can infer the job satisfaction of others by careful observation and interpretation of what people say and do while going about their jobs. Interviews and questionnaires can also be used to more formally examine levels of job satisfaction.[227] Two of the more popular job satisfaction questionnaires used over the years are the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) and the Job Descriptive Index (JDI).[228] Both address components of job satisfaction with which all good managers should be concerned. The MSQ measures satisfaction with working conditions, chances for advancement, freedom to use one's own judgment, praise for doing a good job, and feelings of accomplishment, among others. The five facets of job satisfaction measured by the JDI are

The work itsef—responsibility, interest, and growth

Quality of supervision—technical help and social support

Relationships with co-workers—social harmony and respect

Promotion opportunities—chances for further advancement

Pay—adequacy of pay and perceived equity vis-à-vis others

If you watch or read the news, you'll regularly find reports on the job satisfaction of workers. You'll also find lots of job satisfaction studies in the academic literature. The results don't always agree, but they usually fall within a common range. We can generally conclude that the majority of American workers are at least somewhat satisfied with their jobs, with a recent survey placing this figure at about 65 percent even during a time of economic down-turn.[229] But job satisfaction has been declining for a dozen years or more. It also tends to be higher in small firms and lower in large ones; it tends to be lower among the youngest workers. And, job satisfaction and overall life satisfaction tend to run together.[230] When workers in a global study were asked to report on common job satisfaction or "morale" problems, they identified pay dissatisfaction, number of hours worked, not getting enough holiday or personal time off, lack of flexibility in working hours, and time spent commuting to and from work.[231]

Surely you can agree that job satisfaction is important on quality-of-work-life grounds alone. Don't people deserve to have satisfying work experiences? But is job satisfaction important in other than a "feel good" sense? How does it impact job behaviors and performance?

Withdrawal Behaviors There is a strong relationship between job satisfaction and physical withdrawal behaviors like absenteeism and turnover. Workers who are more satisfied with their jobs are absent less often than those who are dissatisfied. And satisfied workers are more likely to remain with their present employers, while dissatisfied workers are more likely to quit or at least be on the lookout for other jobs.[232] Withdrawal through absenteeism and turnover can be very costly in terms of lost experience, and the expenses for recruiting and training of replacements. In fact, one study found that up or down changes in retention rates result in magnified changes to corporate earnings.[233]

On this issue of turnover and retention, a survey by Salary.com showed not only that employers tend to overestimate the job satisfactions of their employees, they underestimate the amount of job seeking they were doing. Whereas employers estimated that 37 percent of employees were on the lookout for new jobs, 65 percent of the employees said they were actively or passively job seeking by networking, Web surfing, posting resumes, or checking new job possibilities. Millennials in their 20's and early 30's were most likely to engage in these "just-in-case" job seeking activities. The report concluded that "most employers have not placed enough emphasis on important retention strategies.[234]

There is also a relationship between job satisfaction and psychological withdrawal behaviors. These show up in such things as daydreaming, cyber loafing by Internet surfing or personal electronic communications, excessive socializing, and even just giving the appearance of being busy when you're not. Such psychological withdrawal behaviors are forms of work disengagement, something that Gallup researchers say as many as 71 percent of workers report feeling at times.[235]

Organizational Citizenship Job satisfaction is also linked with organizational citizenship behaviors.[236] These are discretionary behaviors, sometimes called "OCBs," that represent a willingness to "go beyond the call of duty" or "go the extra mile" in one's work.[237] A person who is a good organizational citizen does things that although not required of them help others—interpersonal OCBs, or advance the performance of the organization as a whole—organizational OCBs.[238] You might observe interpersonal OCBs in a service worker who is extraordinarily courteous while taking care of an upset customer or a team member who is altruistic in taking on extra tasks when a co-worker is ill or absent. Examples of organizational OCBs are evident as co-workers who are always willing volunteers for special committee or task force assignments, and those who whose voices are always positive when commenting publicly on their employer.

The flip-side of organizational citizenship shows up in a variety of possible counterproductive work behaviors shown in OB Savvy.[239] Often associated with some form of job dissatisfaction, they purposely disrupt relationships, organizational culture or performance in the workplace.[240] Counterproductive workplace behaviors cover a wide range from things like work avoidance to physical and verbal aggression of others to bad mouthing to outright work sabotage to theft.

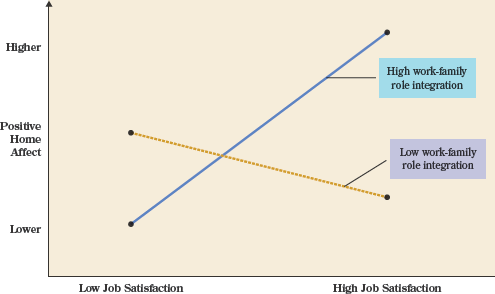

At Home Affect When OB scholars talk about "spillover" effects, they are often referring to how what happens to us at home can affect our work attitudes and behaviors, and how the same holds true as work experiences influence how we feel and behave at home. Research finds that people with higher daily job satisfaction show more positive after-work home affect.[241] In a study that measured spouse or significant other evaluations, more positive at-home affect scores were reported on days when workers experienced higher job satisfaction.[242] Issues of the job satisfaction and at-home affect link are especially significant as workers in today's high-tech and always-connected world struggle with work-life balance.

The importance of job satisfaction can be viewed in the context of two decisions people make about their work—belonging and performing. The first is the decision to belong—that is, to join and remain a member of an organization. This was just discussed in respect to the link between job satisfaction and withdrawal behaviors, both absenteeism and turnover. The second decision, the decision to perform, raises quite another set of issues. We all know that not everyone who belongs to an organization, whether it's a classroom or workplace or sports team or voluntary group, performs up to expectations. So, what is the relationship between job satisfaction and performance?[243] A recent study, for example, finds that higher levels of job satisfaction are related to higher levels of customer ratings received by service workers.[244] But can it be said that high job satisfaction causes high levels of customer service performance?

There is considerable debate on the issue of causality in the satisfaction-performance relationship, with three different positions being advanced. The first is that job satisfaction causes performance; "a happy worker is a productive worker." The second is that performance causes job satisfaction. The third is that job satisfaction and performance are intertwined, influencing one another, and mutually affected by other factors such as the availability of rewards. Perhaps you can make a case for one or more of these positions based on your work experiences.

Satisfaction Causes Performance If job satisfaction causes high levels of performance, the message to managers is: to increase employees' work performance, make them happy. Research, however, finds no simple and direct link between individual job satisfaction at one point in time and later work performance. A sign once posted in a tavern near one of Ford's Michigan plants helps tell the story: "I spend 40 hours a week here, am I supposed to work too?" Even though some evidence exists for the satisfaction → performance relationship among professional or higher-level employees, the best conclusion is that job satisfaction alone is not a consistent predictor of individual work performance.

Performance Causes Satisfaction If high levels of performance cause job satisfaction, the message to managers is quite different. Rather than focusing on job satisfaction as the pathway to performance, attention shifts to creating high performance as a precursor to job satisfaction, that is performance → satisfaction. It generally makes sense that people should feel good about their job when they perform well. And indeed, research does find a link between individual performance measured at one time and later job satisfaction.

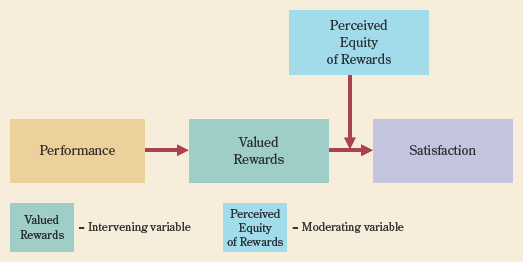

Figure 3.5 shows a basic model explaining this relationship as based on the work of Edward E. Lawler and Lyman Porter. It suggests that performance leads to rewards that, in turn, lead to satisfaction.[245] Rewards are intervening variables that, when valued by the recipient, link performance with later satisfaction. The model also includes a moderator variable—perceived equity of rewards. This indicates that high performance leads to satisfaction only if rewards are perceived as fair and equitable. Although this model is a good starting point, and one that we will use again in discussing motivation and rewards in Chapter 6, we also know from personal experience that some people may perform great but still not like the jobs that they have to do.

Rewards Cause Both Satisfaction and Performance The final position in the job satisfaction-performance discussion builds from and somewhat combines the prior two. It suggests that the right rewards allocated in the right ways will positively influence both performance and satisfaction, which also influence one another. The key issue in respect to the allocation of rewards is performance contingency, or varying the size of the reward in proportion to the level of performance.

Research generally finds that rewards influence satisfaction while performance-contingent rewards influence performance.[246] Thus the management advice is to use performance-contingent rewards well in the attempt to create both. Although giving a low performer a small reward may lead to dissatisfaction at first, the expectation is that he or she will make efforts to improve performance in order to obtain higher rewards in the future.[247]

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 3.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 3 study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

What are emotions and moods?

Emotions are strong feelings directed at someone or something that influence behavior, often with intensity and for short periods of time.

Moods are generalized positive or negative states of mind that can be persistent influences on one's behavior.

Affect is a generic term that covers a broad range of feelings that individuals experience as emotions and moods.

Emotional Intelligence is the ability to detect and manage emotional cues and information. Four emotional intelligence skills or competencies are self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management.

Social emotions refer to individuals' feelings based on information external to them and include pity, envy, scorn, and jealousy; self-conscious emotions include shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride.

How do emotions and moods influence behavior in organizations?

Emotional contagion involves the spillover effects onto others of one's emotions and moods; in other words emotions and moods can spread from person to person.

Emotional labor is a situation where a person displays organizationally desired emotions while performing their jobs.

Emotional dissonance is the discrepancy between true feelings and organizationally desired emotions; it is linked with deep acting to try to modify true inner feelings, and surface acting to hide one's true inner feelings.

Display rules govern the degree to which it is appropriate for people from different cultures to display their emotions similarly.

Affective Events Theory (AET) relates characteristics of the work environment and daily hassles and uplifts to positive and negative emotional reactions and, ultimately, job satisfaction.

What are attitudes?

An attitude is a predisposition to respond in a certain way to people and things.

Attitudes have three components—affective, cognitive, and behavioral.

Although attitudes predispose individuals toward certain behaviors they do not guarantee that such behaviors will take place.

Individuals desire consistency between their attitudes and their behaviors, and cognitive dissonance occurs when a person's attitude and behavior are inconsistent.

Job satisfaction is an attitude toward one's job, co-workers, and workplace.

Job involvement is a positive attitude that shows up in the extent to which an individual is dedicated to a job.

Organizational commitment is a positive attitude that shows up in the loyalty of an individual to the organization.

What is job satisfaction and what are its implications?

Five components of job satisfaction are the work itself, quality of supervision, relationships with co-workers, promotion opportunities, and pay.

Job satisfaction influences withdrawal behaviors such as absenteeism, turnover, day dreaming and cyber loafing.

Job satisfaction is linked with organizational citizenship behaviors that are both interpersonal—such as doing extra work for a sick team mate—and organizational—such as always speaking positively about the organization.

Job dissatisfaction may be reflected in counterproductive work behaviors such as purposely performing with low quality, avoiding work, acting violent at work, or even engaging in workplace theft.

Three possibilities in the job satisfaction and performance relationship are: satisfaction causes performance, performance causes satisfaction, and rewards cause both performance and satisfaction.

Affect (p. 62)

Attitude (p. 70)

Cognitive dissonance (p. 71)

Counterproductive work behaviors (p. 74)

Display rules (p. 68)

Emotions (p. 62)

Emotional dissonance (p. 67)

Employee engagement (p. 72)

Emotional intelligence (p. 62)

Emotion and mood contagion (p. 66)

Emotional labor (p. 66)

Job involvement (p. 72)

Job satisfaction (p. 72)

Moods (p. 65)

Organizational citizenship behaviors (p. 74)

Organizational commitment (p. 72)

Relationship management (p. 63)

Self-awareness (p. 63)

Self-conscious emotions (p. 64)

Self-management (p. 63)

Social awareness (p. 63)

Social emotions (p. 64)

In terms of individual psychology, a/an _____________ represents a rather intense but short-lived feeling about a person or a situation, while a/an _____________ describes a more generalized positive or negative state of mind. (a) stressor, role ambiguity (b) external locus of control, internal locus of control (c) self-serving bias, halo effect (d) emotion, mood

When someone is feeling anger toward something that a co-worker did she is experiencing a/an _____________, but when someone is just "having a bad day overall" he is experiencing a/an _____________. (a) mood, emotion (b) emotion, mood (c) affect, effect (d) dissonance, consonance

Emotions and moods as personal affects are known to influence _____________. (a) attitudes (b) ability (c) aptitude (d) intelligence

In contrast to self-conscious emotions, social emotions such as pity or envy are based on _____________. (a) information from external sources (b) feelings of guilt or pride (c) information from internal sources (d) feelings of shame or embarrassment

The _____________ component of an attitude is what indicates a person's belief about something, while the _____________ component indicates a specific positive or negative feeling about it. (a) cognitive, affective (b) emotional, affective (c) cognitive, mood (d) behavioral, mood

The term used to describe the discomfort someone feels when his or her behavior is inconsistent with an expressed attitude is _____________. (a) alienation (b) cognitive dissonance (c) job dissatisfaction (d) person-job imbalance

Affective Events Theory shows how one's emotional reactions to work events, environment, and personal predispositions can influence _____________. (a) job satisfaction and performance (b) emotional labor (c) emotional intelligence (d) emotional contagion

Deep acting involves _____________ and is linked with the concept of emotional labor. (a) trying to modify your true inner feelings based on display rules (b) appraisal and recognition of emotions in others (c) creation of cognitive dissonance (d) avoidance of emotional contagion

When an airline flight attendant engages in self-regulation to display organizationally desired emotions during his interactions with passengers, this is an example of _____________. (a) emotional labor (b) emotional contagion (c) rational commitment (d) negative affect

A person who is always willing to volunteer for extra work or to help someone else with their work or to contribute personal time to support an organizational social event can be said to be high in _____________. (a) job performance (b) self-serving bias (c) emotional intelligence (d) organizational commitment

Job satisfaction is known from research to be a reasonable predictor of _____________. (a) Type A personality (b) emotional intelligence (c) cognitive dissonance (d) absenteeism

Which statement about employee engagement is most correct? (a) OB researchers are showing little interest in the topic. (b) It can be increased by letting workers know their opinions count. (c) Only persons paid very well show high employee engagement. (d) On any given day as much as 70 percent of workers may be at least somewhat disengaged.

When employers are asked to describe the job satisfactions of their employees and the implications, they often _____________. (a) overestimate job satisfaction (b) underestimate job satisfaction (c) overestimate inclinations to job search (d) underestimate intentions to stay on the job

The best conclusion about job satisfaction in today's workforce is probably that _____________. (a) It isn't an important issue for managers to consider. (b) The only real concern is pay. (c) Most people are not satisfied with their jobs most of the time. (d) Most people are at least somewhat satisfied with their jobs most of the time.

Which statement about the job satisfaction-job performance relationship is most true based on research? (a) A happy worker will be a productive worker. (b) A productive worker will be a happy worker. (c) A productive worker well rewarded for performance will be a happy worker. (d) There is no relationship between being happy and being productive in a job.

What are the major differences between emotions and moods as personal affects?

Compare and contrast the positive and negative aspects of both anger and empathy as common emotions that people may display at work.

List five components of job satisfaction and briefly discuss their importance.

Why is cognitive dissonance an important concept for managers to understand?