chapter at a glance

Organizations today run on the foundation of teams and teamwork. Teams that achieve synergy bring out the best in their members in respect to performance, creativity, and enthusiasm. Here's what to look for in Chapter 7. Don't forget to check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

WHY ARE TEAMS IMPORTANT IN ORGANIZATIONS?

Teams and Teamwork

What Teams Do

Organizations as Networks of Teams

Cross-Functional and Problem-Solving Teams

Virtual Teams

Self-Managing Teams

WHEN IS A TEAM EFFECTIVE?

Criteria of an Effective Team

Synergy and Team Benefits

Social Loafing and Team Problems

WHAT ARE THE STAGES OF TEAM DEVELOPMENT?

Forming Stage

Storming Stage

Norming Stage

Performing Stage

Adjourning Stage

HOW CAN WE UNDERSTAND TEAMS AT WORK?

Team Inputs

Diversity and Team Performance

Team Processes

The world of collegiate athletics is a good place to study teams and teamwork, both the upsides and the downsides. And when talking about the positives, the experience of Sasho Cirovski as head coach of the University of Maryland men's soccer team is worth a look. He has been through many team wins and losses, and he has learned a lot in the process.

There was a time when Cirovski's "Terps" struggled to win after having a series of winning seasons. What was going wrong? Cirovski attributed the problem to a lack of team leadership. So he appointed his two best players to be the leaders. But still the team lagged. The impact of the team leaders wasn't showing up on the playing field. Cirovski says: "I was recruiting talent. I wasn't doing a good job of recruiting leaders."

"I was recruiting talent. I wasn't doing a good job of recruiting leaders."

For help, Cirovski turned to the business world and sought advice from his brother, Vancho, a human resources vice president at Cardinal Health. His brother suggested taking a survey of team members to find out who they most relied on for advice and motivation. The goal was to find the natural team leaders, not just the most visible star players. This shifted the focus toward identifying players who were already acting as natural leaders and who would be supported by the whole team. The survey revealed that one of the players was a huge positive influence—Scotty Buete, a sophomore whom Cirovski had not thought about. He was "off the leadership radar," so to speak.

Cirovski moved quickly and appointed Scotty Buete to be the third team captain, telling him: "Everyone is looking for you to lead." And lead Buete did. Cirovski says "Scotty was the glue, and I didn't see it." From that point on the Terps were back in contention. And as a side benefit, Cirovski's team survey also identified two other younger players with strong leadership potential.

synergy is the goal, but it's not guaranteed

The fact is that there is a lot more to teamwork than simply assigning members to the same group, calling it a "team," appointing someone as "team leader," and then expecting them all to do a great job.[349] That's part of the lesson in the opening example of Sasho Cirovski and the University of Maryland soccer team. And it is a good introduction to the four chapters in this part of the book that are devoted to an understanding of teams and team processes. As the discussion begins, it helps to remember that the responsibilities for building high-performance, teams rest not only with the manager, coach, or team leader, but also with the team members themselves. If you look now at OB Savvy 7.1, you'll find a checklist of several must-have team contributions, the types of things that team members and leaders can do to help their teams achieve high performance.[350]

When we think of the word "team," a variety of popular sporting teams might first come to mind, perhaps a college favorite like the University of Maryland "Terps," or professionals like the Cleveland Cavaliers or the St. Louis Cardinals. Just pick your sport.

- Scene—NBA Basketball:

Scholars find that both good and bad basketball teams win more games the longer the players have been together. Why? They claim it's a "teamwork effect" that creates wins because players know each other's moves and playing tendencies.[351]

But let's not forget that teams are important in work settings as well. And whether or not a team lives up to expectations can have a major impact on how well its customers and clients are served.

- Scene—Hospital Operating Room:

Scholars notice that the same heart surgeons have lower death rates for similar procedures when performed in hospitals where they do more operations. Why? They claim it's because the doctors spend more time working together with members of these surgery teams. The scholars argue it's not only the surgeon's skills that count: "the skills of the team, and of the organization, matter."[352]

What is going on in these examples? Whereas a group of people milling around a coffee shop counter is just that—a "group" of people—teams like those in the examples are supposed to be something more: "groups+" if you will. That is what distinguishes the successful NBA basketball teams from the also-rans and the best surgery teams from all the others. In OB we define a team as a group of people brought together to use their complementary skills to achieve a common purpose for which they are collectively accountable.[353] Real teamwork occurs when team members accept and live up to their collective accountability by actively working together so that all their respective skills are best used to achieve important goals.[354]

A team is a group of people holding themselves collectively accountable for using complimentary skills to achieve a common purpose.

Teamwork occurs when team members live up to their collective accountability for goal accomplishment.

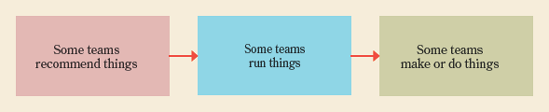

When we talk about teams in organizations, one of the first things to recognize is that they do many things and make many types of performance contributions. In general we can describe them as teams that recommend things, run things, and make or do things.[355]

First, there are teams that recommend things. Established to study specific problems and recommend solutions for them, these teams typically work with a target completion date and often disband once the purpose has been fulfilled. These teams include task forces, ad hoc committees, special project teams, and the like. Members of these teams must be able to learn quickly how to work well together, accomplish the assigned task, and make good action recommendations for follow-up work by other people.

Second, there are teams that run things. Such management teams consist of people with the formal responsibility for leading other groups. These teams may exist at all levels of responsibility, from the individual work unit composed of a team leader and team members to the top-management team composed of a CEO and other senior executives. Key issues addressed by top-management teams include, for example, identifying overall organizational purposes, goals, and values, as well as crafting strategies and persuading others to support them.[356]

Third, there are teams that make or do things. These are teams and work units that perform ongoing tasks such as marketing, sales, systems analysis, or manufacturing. Members of these teams must have effective long-term working relationships with one another, solid operating systems, and the external support needed to achieve effectiveness over a sustained period of time. They also need energy to keep up the pace and meet the day-to-day challenges of sustained high performance.

When it was time to reengineer its order-to-delivery process to streamline a noncompetitive and costly cycle time, Hewlett-Packard turned to a team. In just nine months, they had slashed the time, improved service, and cut costs. How did they do it? Team leader Julie Anderson said: "We took things away: no supervisors, no hierarchy, no titles, no job descriptions ... the idea was to create a sense of personal ownership." One team member said, "No individual is going to have the best idea, that's not the way it works—the best ideas come from the collective intelligence of the team."[357] This isn't an isolated example. Organizations everywhere are using teams and teamwork to improve performance. The catchwords of these new approaches are empowerment, participation, and involvement.

The many formal teams found in organizations are created and officially designated to serve specific organizational purposes. Some are permanent and ongoing. They appear on organization charts as departments (e.g., market research department), divisions (e.g., consumer products division), or teams (e.g., product-assembly team). Such teams can vary in size from very small departments or teams of just a few people to large divisions employing a hundred or more people. Other formal teams are temporary and short lived. They are created to solve specific problems or perform defined tasks and are then disbanded once the purpose has been accomplished. Examples include the many temporary committees and task forces that are important components of any organization.[358]

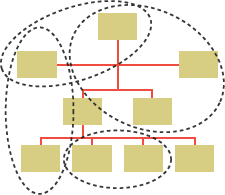

One way to view organizations is as interlocking networks of permanent and temporary teams. On the vertical dimension the manager is a linchpin serving as a team leader at one level and a team member at the next higher level.[359] On the horizontal dimension, for example, a customer service team member may also serve on a special task force for new product development and head a committee set up to examine a sexual harassment case.

In addition to their networks of formal teams, Figure 7.1 also shows that organizations have vast networks of informal groups that emerge and coexist as a shadow to the formal structure and without any formal purpose or official endorsement. These informal groups form spontaneously through personal relationships or special interests and create their own interlocking networks of relationships within the organization. Friendship groups, for example, consist of persons with natural affinities for one another. They tend to work together, sit together, take breaks together, and even do things together outside of the workplace. Interest groups consist of persons who share common interests. These may be job-related interests, such as an intense desire to learn more about computers, or nonwork interests, such as community service, sports, or religion.

Although informal groups can be places where people join to complain, spread rumors, and disagree with what is happening in the organization, they can be quite functional as well. Informal networks can speed up workflows as people assist each other in ways that cut across the formal structures. They can also help satisfy needs, for example by providing social companionship or a sense of personal importance that is otherwise missing in someone's formal team assignments.

A tool known as social network analysis is used to identify the informal groups and networks of relationships that are active in an organization. Such an analysis typically asks people to identify co-workers who help them most often, who communicate with them regularly, and who energize and de-energize them. When results are analyzed, social networks are drawn with lines running from person to person according to frequency and type of relationship maintained. This map shows how a lot of work really gets done in organizations, in contrast to the formal arrangements depicted on organization charts. Managers use such information to redesign the formal team structure for better performance and also to legitimate informal networks as pathways to high performance for people in their daily work.

Management scholar Jay Conger calls the organization built around teams and teamwork the management system of the future and the best response to the needs for speed and adaptability in an ever-more-competitive environment.[360] He cites the example of an American jet engine manufacturer that changed from a traditional structure of functional work units to one in which people from different functions worked together in teams. The new approach cut the time required to design and produce new engines by 50 percent. Conger calls such "cross-functional" teams "speed machines."[361]

A cross-functional team consists of members assigned from different functional departments or work units. It plays an important role in efforts to achieve more horizontal integration and better lateral relations. Members of cross-functional teams are expected to work together with a positive combination of functional expertise and integrative or total systems thinking. The expected result is higher performance driven by the advantages of better information and faster decision making.

A cross-functional team has members from different functions or work units.

Cross-functional teams are a way of trying to beat the functional silos problem, also called the functional chimneys problem. It occurs when members of functional units stay focused on matters internal to their function and minimize their interactions with members dealing with other functions. In this sense, the functional departments or work teams create artificial boundaries, or "silos," that discourage rather than encourage interaction with other units. The result is poor integration and poor coordination with other parts of the organization. The use of cross-functional teams is a way to break down the barriers among functional units by creating a forum in which members from different functions work together as one team with a common purpose.[362]

The functional silos problem occurs when members of one functional team fail to interact with others from other functional teams.

Organizations also use any number of problem-solving teams, which are created temporarily to serve a specific purpose by dealing with a specific problem or opportunity. They exist as the many committees, task forces, and special project teams that are common facts of working life. The president of a company, for example, might convene a task force to examine the possibility of implementing flexible work hours for employees; a human resource director might bring together a committee to advise her on changes in employee benefit policies; a project team might be formed to plan and implement a new organization-wide information system. Temporary teams like these are usually headed by chairpersons or team leaders who are held accountable for meeting the task force goal or fulfilling the committee's purpose, much as is the manager of a formal work unit.

The term employee involvement team applies to a wide variety of teams whose members meet regularly to collectively examine important workplace issues. They might discuss, for example, ways to enhance quality, better satisfy customers, raise productivity, and improve the quality of work life. In this way, employee involvement teams mobilize the full extent of workers' know-how and gain the commitment needed to fully implement solutions. An example is what some organizations call a quality circle—a small team of persons who meet periodically to discuss and develop solutions for problems relating to quality and productivity.[363]

An employee involvement team meets regularly to address workplace issues.

A quality circle team meets regularly to address quality issues.

Information technology has brought a new type of group into the workplace. This is the virtual team, whose members convene and work together electronically via computers.[364] It used to be that teamwork was confined in concept and practice to those circumstances in which members could meet face to face. The advent of new technologies and computer programs have changed all that. Working in electronic space and free from the constraints of geographical distance, members of virtual teams can do the same things in computer networks as do members of face-to-face groups: share information, make decisions, and complete tasks.

Members of virtual teams work together through computer mediation.

In terms of potential advantages, virtual teams bring together people who may be located at great distances from one another.[365] This offers obvious cost and time efficiencies. The electronic rather than face-to-face environment of the virtual team can help focus interaction and decision making on objective information rather than emotional considerations and distracting interpersonal problems. In addition, discussions and information shared among team members can also be electronically stored for continuous access and historical record keeping.

Many of the downsides to virtual teams occur for the same reasons they do in other groups. Members of virtual teams can have difficulties establishing good working relationships. When the computer is the go-between, relationships and interactions among virtual team members are different from those of face-to-face settings. The lack of face-to-face interaction limits the role of emotions and nonverbal cues in the communication process, perhaps depersonalizing relations among team members.

Some steps to successful teams are summarized in Mastering Management, and in many ways they mirror in electronic space the essentials of good team leadership in face-to-face teams.[366] Managers and team leaders should also understand that the computer technology should be appropriate to the task, and that team members should be well trained in using it. Finally, researchers note that virtual teams may work best when the tasks are more structured and the work is less interdependent.

In the last chapter we discussed job enrichment and its implications for individual motivation and performance. Now we can talk about a form of job enrichment for teams. A high-involvement work-group design that is becoming increasingly well established is known as the self-managing team. Sometimes called self-directed work teams, these are small groups empowered to make the decisions needed to manage themselves on a day-to-day basis.[367]

Self-managing teams basically replace traditional work units with teams whose members assume duties otherwise performed by a manager or first-line supervisor. Figure 7.2 shows that members of true self-managing teams make their own decisions about scheduling work, allocating tasks, training for job skills, evaluating performance, selecting new team members, and controlling the quality of work.

A self-managing team should probably include between 5 and 15 members. The teams need to be large enough to provide a good mix of skills and resources but small enough to function efficiently. Because team members have a lot of discretion in determining work pace and in distributing tasks, multiskilling is important. This means that team members are expected to perform many different jobs—even all of the team's jobs—as needed. Ideally, the more skills someone masters, the higher his or her base pay. Team members should also be responsible for conducting training and certifying one another as having mastered various skills.

The expected benefits of self-managing teams include productivity and quality improvements, production flexibility and faster response to technological change, reduced absenteeism and turnover, and improved work attitudes and quality of work life. But just as with all organizational changes, the shift from traditional work units to self-managing teams may have its difficulties. It may be hard for some team members to adjust to the "self-managing" responsibilities. And higher-level managers may have problems dealing with the loss of the first-line supervisor positions; they must learn to deal with teams instead of the individual supervisors as direct reporters. Given all this, self-managing teams are probably not right for all organizations, work situations, and people. They have great potential, but they also require a proper setting and a great deal of management support. At a minimum, the essence of any self-managing team—high involvement, participation, and empowerment—must be consistent with the values and culture of the organization.

There is no doubt that teams are pervasive and important in organizations; they accomplish important tasks and help members achieve satisfaction in their work. But we also know from personal experiences that teams and teamwork have their difficulties; not all teams perform well, and not all team members are always satisfied. Surely you've heard the sayings "a camel is a horse put together by a committee" and "too many cooks spoil the broth." They raise an important question: Just what are the foundations of team effectiveness?

Teams, just like individuals, should be held accountable for their performance. And to do this we need to have some understanding of team effectiveness. In OB we define an effective team as one that achieves high levels of task performance, member satisfaction, and team viability.

With regard to task performance, an effective team achieves its performance goals in the standard sense of quantity, quality, and timeliness of work results. For a formal work unit such as a manufacturing team this may mean meeting daily production targets. For a temporary team such as a new policy task force this may involve meeting a deadline for submitting a new organizational policy to the company president.

With regard to member satisfaction, an effective team is one whose members believe that their participation and experiences are positive and meet important personal needs. They are satisfied with their tasks, accomplishments, and interpersonal relationships. With regard to team viability, the members of an effective team are sufficiently satisfied to continue working well together on an ongoing basis and/or to look forward to working together again at some future point in time. Such a group has all-important long-term performance potential.

When teams are effective, they offer the potential for synergy—the creation of a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. Synergy works within a team and it works across teams as their collective efforts are harnessed to serve the organization as a whole. As noted in the chapter subtitle, synergy is the goal, and it always should be. It creates the great beauty of teams: people working together and accomplishing more through teamwork than they ever could by working alone. In general we can say that:

Synergy is the creation of a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

Teams are good for people.

Teams can improve creativity.

Teams can make better decisions.

Teams can increase commitments to action.

Teams help control their members.

Teams help offset large organization size.

The performance advantages of teams over individuals acting alone are most evident in three situations.[368] First, when there is no clear "expert" for a particular task or problem, teams seem to make better judgments than does the average individual alone. Second, teams are typically more successful than individuals when problems are complex, requiring a division of labor and the sharing of information. Third, because of their tendencies to make riskier decisions, teams can be more creative and innovative than individuals.

Teams are beneficial as settings where people learn from one another and share job skills and knowledge. The learning environment and the pool of experience within a team can be used to solve difficult and unique problems. This is especially helpful to newcomers, who often need help in their jobs. When team members support and help each other in acquiring and improving job competencies, they may even make up for deficiencies in organizational training systems.

Teams are also important sources of need satisfaction for their members. Opportunities for social interaction within a team can provide individuals with a sense of security through work assistance and technical advice. Team members can also provide emotional support for one another in times of special crisis or pressure. And the many contributions individuals make to teams can help members experience self-esteem and personal involvement.

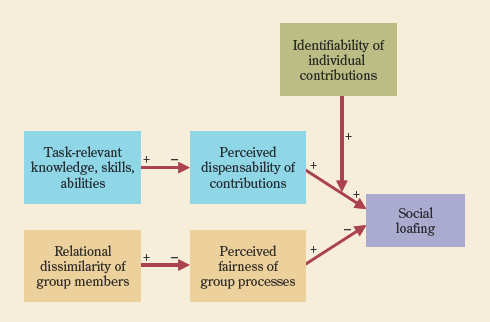

Although teams have enormous performance potential, they can also have problems. One concern is social loafing, also known as the Ringlemann effect. It is the tendency of people to work less hard in a group than they would individually.[369] Max Ringlemann, a German psychologist, pinpointed the phenomenon by asking people to pull on a rope as hard as they could, first alone and then as part of a team.[370] He found that average productivity dropped as more people joined the rope-pulling task. He suggested that people may not work as hard in groups because their individual contributions are less noticeable in the group context and because they prefer to see others carry the workload.

You may have encountered social loafing in your work and study teams, and been perplexed in terms of how to best handle it. Perhaps you have even been surprised at your own social loafing in some performance situations. Rather than give in to the phenomenon and its potential performance losses, social loafing can often be reversed or prevented. Steps that team leaders can take include keeping group size small and redefining roles so that free-riders are more visible and peer pressures to perform are more likely, increasing accountability by making individual performance expectations clear and specific, and making rewards directly contingent on an individual's performance contributions.[371]

This discussion moves us to another concept known as social facilitation—the tendency for one's behavior to be influenced by the presence of others in a group or social setting.[372] In a team context social facilitation can be a boost or a detriment to an individual member's performance contributions. Social facilitation theory suggests that working in the presence of others creates an emotional arousal or excitement that stimulates behavior and therefore affects performance. The effect works to the positive and stimulates extra effort when one is proficient with the task at hand. An example is the team member who enthusiastically responds when asked to do something she is really good at, such as making Power Point slides for a team presentation. But the effect of social facilitation can be negative when the task is unfamiliar or a person lacks the necessary skills. A team member might withdraw or even tend toward social loafing, for example, when asked to do something he isn't very good at, such as being included among those delivering the team's final presentation in front of a class or larger audience.

Social facilitation is the tendency for one's behavior to be influenced by the presence of others in a group.

Other common problems of teams include personality conflicts and differences in work styles that antagonize others and disrupt relationships and accomplishments. Sometimes team members withdraw from active participation due to uncertainty over tasks or battles about goals or competing visions. Ambiguous agendas or ill-defined problems can also cause fatigue and loss of motivation when teams work too long on the wrong things with little to show for it. And finally, not everyone is always ready to do group work. This might be due to lack of motivation, but it may also stem from conflicts with other work deadlines and priorities. Low enthusiasm may also result from perceptions of poor team organization or progress, as well as from meetings that seem to lack purpose. These and other difficulties can easily turn the great potential of teams into frustration and failure.

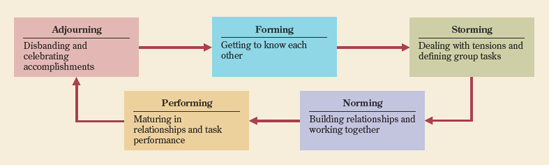

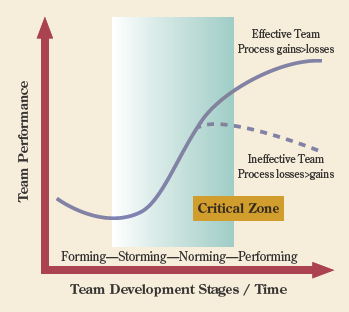

There is no doubt that groups can be great resources for organizations, creating synergies and helping to accomplish things that are far beyond the efforts of any individual. But the pathways to team effectiveness are often complicated and challenging. One of the first things to consider, whether we are talking about a formal work unit, a task force, a virtual team, or a self-managing team, is the fact that the team passes through a series of life cycle stages.[373] Depending on the stage the team has reached, the leader and members can face very different challenges and the team may be more or less effective. Figure 7.3 describes the five stages of team development as forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning.[374]

In the forming stage of team development, a primary concern is the initial entry of members to a group. During this stage, individuals ask a number of questions as they begin to identify with other group members and with the team itself. Their concerns may include "What can the group offer me?" "What will I be asked to contribute?" "Can my needs be met at the same time that I contribute to the group?" Members are interested in getting to know each other and discovering what is considered acceptable behavior, in determining the real task of the team, and in defining group rules.

The storming stage of team development is a period of high emotionality and tension among the group members. During this stage, hostility and infighting may occur, and the team typically experiences many changes. Coalitions or cliques may form as individuals compete to impose their preferences on the group and to achieve a desired status position. Outside demands such as premature performance expectations may create uncomfortable pressures. In the process, membership expectations tend to be clarified, and attention shifts toward obstacles standing in the way of team goals. Individuals begin to understand one another's interpersonal styles, and efforts are made to find ways to accomplish team goals while also satisfying individual needs.

The norming stage of team development, sometimes called initial integration, is the point at which the members really start to come together as a coordinated unit. The turmoil of the storming stage gives way to a precarious balancing of forces. With the pleasures of a new sense of harmony, team members will strive to maintain positive balance. Holding the team together may become more important to some than successfully working on the team tasks. Minority viewpoints, deviations from team directions, and criticisms may be discouraged as members experience a preliminary sense of closeness. Some members may mistakenly perceive this stage as one of ultimate maturity. In fact, a premature sense of accomplishment at this point needs to be carefully managed as a stepping stone to the next level of team development—performing.

The performing stage of team development, sometimes called total integration, marks the emergence of a mature, organized, and well-functioning team. Team members are now able to deal with complex tasks and handle internal disagreements in creative ways. The structure is stable, and members are motivated by team goals and are generally satisfied. The primary challenges are continued efforts to improve relationships and performance. Team members should be able to adapt successfully as opportunities and demands change over time. A team that has achieved the level of total integration typically scores high on the criteria of team maturity as shown in Figure 7.4.

A well-integrated team is able to disband, if required, when its work is accomplished. The adjourning stage of team development is especially important for the many temporary teams such as task forces, committees, project teams, and the like. Their members must be able to convene quickly, do their jobs on a tight schedule, and then adjourn—often to reconvene later if needed. Their willingness to disband when the job is done and to work well together in future responsibilities, team or otherwise, is an important long-term test of team success.

Procter & Gamble's former CEO A. G. Lafley says that team effectiveness comes together when you have "the right players in the right seats on the same bus, headed in the same direction."[375] This wisdom is quite consistent with the findings of OB scholars. The open systems model in Figure 7.5 shows team effectiveness being influenced by both inputs—"right players in the right seats," and by processes—"on the same bus, headed in the same direction."[376] You can remember the implications of this figure by this equation:

| Team effectiveness = Quality of inputs + (Process gains − Process losses) |

The inputs to a team are the initial "givens" in the situation. They set the foundations for all subsequent action; the stronger the input foundations, the better the chances for long-term team effectiveness. Key team inputs include resources and setting, the nature of the task, team size, and team composition.

![An open-systems model of team effectiveness. [Source: John R. Schermerhorn, Jr., Management, Tenth Edition (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), used by permission].](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/business/42/9780470294413/9780470294413__organizational-behavior-11th__9780470294413__figs__0705.png)

Figure 7.5. An open-systems model of team effectiveness. [Source: John R. Schermerhorn, Jr., Management, Tenth Edition (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), used by permission].

Resources and setting Appropriate goals, well-designed reward systems, adequate resources, and appropriate technology are all essential to support the work of teams. Just as an individual's performance, team performance can suffer when goals are unclear, insufficiently challenging, or arbitrarily imposed. It can also suffer if goals and rewards are focused too much on individual-level instead of group-level accomplishments. In addition, it can suffer when resources—information, budgets, work space, deadlines, rules and procedures, technologies, and the like—are insufficient to accomplish the task. By contrast, having a supportive organizational setting within which to work can be a strong launching pad for team success.

The importance of setting and support in the new, team-based organization designs is evident in the attention now being given to things like office architecture and how well it supports teamwork. At SEI Investments, for example, employees work in a large, open space without cubicles or dividers. Each person has a private set of office furniture and fixtures, but all on wheels. Technology easily plugs and unplugs from suspended power beams that run overhead. This makes it easy for project teams to convene and disband as needed and for people to meet and converse intensely within the ebb and flow of daily work.[377]

Nature of the Task The tasks they are asked to perform can place different demands on teams, with varying implications for group effectiveness. When tasks are clear and well defined, it is easier for members to both know what they are trying to accomplish and to work together while doing it. But team effectiveness is harder to achieve when the task is highly complex.[378] Complex tasks require lots of information exchange and intense interaction, and this all takes place under conditions of some uncertainty. To deal well with complexity, team members have to fully mobilize their talents and use the available resources well if they are to achieve desired results. Success at complex tasks, however, is a source of high satisfaction for team members.

One way to analyze the nature of the team task is in terms of its technical and social demands. The technical demands of a group's task include the degree to which it is routine or not, the level of difficulty involved, and the information requirements. The social demands of a task involve the degree to which issues of interpersonal relationships, egos, controversies over ends and means, and the like come into play. Tasks that are complex in technical demands require unique solutions and more information processing; those that are complex in social demands involve difficulties reaching agreement on goals or methods for accomplishing them.

Team Size The size of a team, as measured by the number of its members, can have an impact on team effectiveness. As a team becomes larger, more people are available to divide up the work and accomplish needed tasks. This can boost performance and member satisfaction, but only up to a point. As teams grow in size, communication and coordination problems often set in due to the sheer number of linkages that must be maintained. Satisfaction may dip, and turnover, absenteeism, and social loafing may increase. Even logistical matters, such as finding time and locations for meetings, become more difficult for larger groups and can hurt performance.[379] Amazon.com's founder and CEO, Jeff Bezos, is a great fan of teams. But he also has a simple rule when it comes to the size of product development teams: No team should be larger than two pizzas can feed.[380]

A good size for problem-solving teams is between five and seven members. Chances are that fewer than five may be too small to adequately share all the team responsibilities. With more than seven, however, individuals may find it harder to join in the discussions, contribute their talents, and offer ideas. Larger teams are also more prone to possible domination by aggressive members and have tendencies to split into coalitions or subgroups.[381] When voting is required, odd-numbered teams are preferred to help rule out tie votes. But when careful deliberations are required and the emphasis is more on consensus, such as in jury duty or very complex problem solving, even-numbered teams may be more effective because members are forced to confront disagreements and deadlocks rather than simply resolve them by majority voting.[382]

Team Composition "If you want a team to perform well, you've got to put the right members on the team to begin with." Does that advice sound useful? It's something we hear a lot in training programs with executives. There is no doubt that one of the most important input factors is the team composition. You can think of this as the mix of abilities, skills, backgrounds, and experiences that the members bring to the team.

The basic rule of thumb for team composition is to choose members whose talents and interests fit well with the tasks to be accomplished and whose personal characteristics increase the likelihood of being able to work well with others. In this sense ability counts; it's probably the first thing to consider in selecting members for a team. The team is more likely to perform better when its members have skills and competencies that best fit task demands. Although talents alone cannot guarantee desired results, they establish an important baseline of high performance potential.

Surely you've been on teams or observed teams where there was lots of talent but very little teamwork. A likely cause is that the blend of members caused relationship problems over everything from needs to personality to experience to age and other background characteristics. In this respect, the FIRO-B theory (with FIRO standing for "fundamental interpersonal orientation") identifies differences in how people relate to one another in groups based on their needs to express and receive feelings of inclusion, control, and affection.[383] Developed by William Schultz, the theory suggests that teams whose members have compatible needs are likely to be more effective than teams whose members are more incompatible. Symptoms of incompatibilities include withdrawn members, open hostilities, struggles over control, and domination by a few members. Schultz states the management implications of the FIRO-B theory this way: "If at the outset we can choose a group of people who can work together harmoniously, we shall go far toward avoiding situations where a group's efforts are wasted in interpersonal conflicts."[384]

FIRO-B theory examines differences in how people relate to one another based on their needs to express and receive feelings of inclusion, control, and affection.

In homogeneous teams where members are very similar to one another, teamwork usually isn't much of a problem. The members typically find it quite easy to work together and enjoy the team experience. But researchers warn about the risks of homogeneity. When team members are too similar in background, training, and experience, they tend to underperform even though the members may feel very comfortable with one another.[385]

In homogeneous teams members share many similar characteristics.

In heterogeneous teams where members are very dissimilar, teamwork problems are more likely. The mix of diverse personalities, experiences, backgrounds, ages, and other personal characteristics may create difficulties as members try to define problems, share information, mobilize talents, and deal with obstacles or opportunities. Nevertheless, if, and this is a big "if," members can work well together, the diversity can be a source of advantage and enhanced performance potential.[386]

In heterogeneous teams members differ on many characteristics.

Another issue in team composition is status—a person's relative rank, prestige, or social standing. Status within a team can be based on any number of factors, including age, work seniority, occupation, education, performance, or reputation for performance on other teams. Status congruence occurs when a person's position within the team is equivalent in status to positions the individual holds outside of it. Any status incongruence can create problems for teams. In high-power-distance cultures such as Malaysia, for example, the chair of a committee is expected to be the highest-ranking member of the group. When this is the case the status congruity helps members feel comfortable in proceeding with their work. But if the senior member is not appointed to head the committee, perhaps because an expatriate manager from another culture selected the chair on some other criterion, members are likely to feel uncomfortable and have difficulty working. Similar problems might occur, for example, when a young college graduate in his or her first job is appointed to chair a project team composed of senior and more experienced workers.

Status congruence involves consistency between a person's status within and outside a group.

As discussed in respect to team composition, team diversity in the form of different values, personalities, experiences, demographics, and cultures among the members, is an important team input. And it can pose both opportunities and problems.[387] We have already noted that when teams are relatively homogeneous, displaying little or no diversity, it is probably easier for members to quickly build social relationships and engage in the interactions needed for teamwork. But the lack of diversity may foster narrow viewpoints and otherwise limit the team in terms of ideas, perspectives, and creativity. When teams are more heterogeneous, having a diverse membership, they gain potential advantages in these latter respects; there are more resources and viewpoints available to engage in problem solving, especially when tasks are complex and demanding. Yet these advantages are not automatic; the diversity must be tapped if the team is to realize the performance benefits.[388]

Performance difficulties due to diversity issues are especially likely in the initial stages of team development. What is called the diversity—consensus dilemma is the tendency for the existence of diversity among group members to make it harder for them to work together, even though the diversity itself expands the skills and perspectives available for problem solving.[389] These dilemmas may be most pronounced in the critical zone of the storming and norming stages of development as described in Figure 7.6. Problems may occur in this zone as interpersonal stresses and conflicts emerge from the heterogeneity. The challenge to effectiveness in a multinational team, for example, is to take advantage of the diversity without suffering process disadvantages.[390]

Diversity—consensus dilemma is the tendency for diversity in groups to create process difficulties even as it offers improved potential for problem solving.

Working through the diversity-consensus dilemma can slow team development and impede relationship building, information sharing, and problem solving. But if and when such difficulties are resolved, diverse teams can emerge from the critical zone shown in the figure to achieve effectiveness and often outperform less diverse ones. In this regard Scholar Brian Uzzi reminds us to take a broad view; diversity in team dynamics means more than gender, race, and ethnicity. He points out that when teams lack diversity of backgrounds, training, and experiences, members tend to feel comfortable with one another, but their teams tend to underperform.[391] For example, research shows that the most creative teams include a mix of experienced people and others whom they haven't worked with before.[392] The "old timers" have the experience and connections; the newcomers bring in new talents and fresh thinking.

Casey Stengel, a famous baseball manager, once said: "Getting good players is easy. Getting them to play together is the hard part." His comment certainly rings true in respect to the discussion we just had on diversity and team performance. There is no doubt that the effectiveness of any team requires more than having the right inputs. To achieve effectiveness, team members must work well together to turn the available inputs into the desired outputs. Here again, it's helpful to remember the equation: Team Effectiveness = Quality of inputs + (Process gains − Process losses).

When it comes to analyzing how well people "work together" in teams and whether or not process gains exceed process losses, the focus is on critical group dynamics—the forces operating in teams that affect the way members relate to and work with one another. George Homans described group dynamics in terms of required behaviors—those formally defined and expected by the team—and emergent behaviors—those that team members display in addition to any requirements.[393]

You can think of required behaviors as things like punctuality, respect for customers, and assistance to co-workers. An example of emergent behaviors might be someone taking the time to send an e-mail message to an absent member to keep her informed about what happened during a group meeting. Such helpful emergent behaviors are often essential in moving teams toward effectiveness. But emergent behaviors can be disruptive and harmful as well. A common example is when some team members spend more time discussing and laughing about personal issues than they do working on the team tasks. Another disturbing example involves unethical practices such as the "cheating" discussed in the Ethics in OB box.

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 7.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 7 study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

What do teams do in organizations?

A team is a group of people working together to achieve a common purpose for which they hold themselves collectively accountable.

Teams help organizations by improving task performance; teams help members experience satisfaction from their work.

Teams in organizations serve different purposes—some teams run things, some teams recommend things, and some teams make or do things.

Organizations consist of formal teams that are designated by the organization to serve an official purpose and informal groups that emerge from special interests and relationships but are not part of an organization's formal structure.

Organizations can be viewed as interlocking networks of permanent teams such as project teams and cross-functional teams, as well as temporary teams such as committees and task forces.

Virtual teams, whose members meet and work together through computer mediation, are increasingly common and pose special management challenges.

Members of self-managing teams typically plan, complete, and evaluate their own work, train and evaluate one another in job tasks, and share tasks and responsibilities.

When is a team effective?

An effective team achieves high levels of task accomplishment, member satisfaction, and viability to perform successfully over the long term.

Teams help organizations through synergy in task performance, the creation of a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Teams help satisfy important needs for their members by providing them with things like job support and social interactions.

Team performance can suffer from social loafing when a member slacks off and lets others do the work.

Social facilitation occurs when the behavior of individuals is influenced positively or negatively by the presence of others in a team.

What are the stages of team development?

Teams pass through various stages of development during their life cycles, and each stage poses somewhat distinct management problems.

In the forming stage, team members first come together and form initial impressions; it is a time of task orientation and interpersonal testing.

In the storming stage, team members struggle to deal with expectations and status; it is a time when conflicts over tasks and how the team works are likely.

In the norming or initial integration stage, team members start to come together around rules of behavior and what needs to be accomplished; it is a time of growing cooperation.

In the performing or total integration stage, team members are well-organized and well-functioning; it is a time of team maturity when performance of even complex tasks becomes possible.

In the adjourning stage, team members achieve closure on task performance and their personal relationships; it is a time of managing task completion and the process of disbanding.

How do teams work?

Teams are open systems that interact with their environments to obtain resources that are transformed into outputs.

The equation summarizing the implications of the open systems model for team performance is: Team Effectiveness = Quality of Inputs × (Process Gains − Process Losses).

Input factors such as resources and organizational setting, the nature of the task, team size, and team composition, establish the core performance foundations of a team.

Team processes include basic group dynamics, the way members work together to use inputs and complete tasks.

Important team processes include member entry, task and maintenance leadership, roles and role dynamics, norms, cohesiveness, communications, decision making, conflict, and negotiation.

Cross-functional team (p. 159)

Diversity-consensus dilemma (p. 172)

Effective team (p. 163)

Employee involvement team (p. 160)

FIRO-B theory (p. 171)

Formal teams (p. 158)

Functional silos problem (p. 159)

Group dynamics (p. 173)

Heterogeneous teams (p. 171)

Homogeneous teams (p. 171)

Informal groups (p. 158)

Multiskilling (p. 161)

Problem-solving team (p. 159)

Quality circle (p. 160)

Self-managing team (p. 161)

Social facilitation (p. 164)

Social loafing (p. 164)

Social network analysis (p. 159)

Status congruence (p. 171)

Synergy (p. 163)

Team (p. 156)

Teamwork (p. 156)

Virtual team (p. 160)

The FIRO-B theory deals with ____________ in teams. (a) membership compatibilities (b) social loafing (c) dominating members (d) conformity

It is during the ____________ stage of team development that members begin to come together as a coordinated unit. (a) storming (b) norming (c) performing (d) total integration

An effective team is defined as one that achieves high levels of task performance, member satisfaction, and ____________. (a) coordination (b) harmony (c) creativity (d) team viability

Task characteristics, reward systems, and team size are all ____________ that can make a difference in group effectiveness. (a) group processes (b) group dynamics (c) group inputs (d) human resource maintenance factors

The best size for a problem-solving team is usually ____________ members. (a) no more than 3 or 4 (b) 5 to 7 (c) 8 to 10 (d) around 12 to 13

When a new team member is anxious about questions such as "Will I be able to influence what takes place?" the underlying issue is one of ____________. (a) relationships (b) goals (c) processes (d) control

Self-managing teams ____________. (a) reduce the number of different job tasks members need to master (b) largely eliminate the need for a traditional supervisor (c) rely heavily on outside training to maintain job skills (d) add another management layer to overhead costs

Which statement about self-managing teams is correct? (a) They can improve performance but not satisfaction. (b) They should have limited decision-making authority. (c) They should operate without any team leaders. (d) They should let members plan their own work schedules.

When a team of people is able to achieve more than what its members could by working individually, this is called ____________. (a) distributed leadership (b) consensus (c) team viability (d) synergy

Members of a team tend to become more motivated and better able to deal with conflict during the ____________ stage of team development. (a) forming (b) norming (c) performing (d) adjourning

The Ringlemann effect describes ____________. (a) the tendency of groups to make risky decisions (b) social loafing (c) social facilitation (d) the satisfaction of members' social needs

Members of a multinational task force in a large international business should probably be aware that ____________ might initially slow the progress of the team in meeting its task objectives. (a) synergy (b) groupthink (c) the diversity-consensus dilemma (d) intergroup dynamics

When a team member engages in social loafing, one of the recommended strategies for dealing with this situation is to ____________. (a) forget about it (b) ask another member to force this person to work harder (c) give the person extra rewards and hope he or she will feel guilty (d) better define member roles to improve individual accountability

When a person holds a prestigious position as a vice president in a top management team, but is considered just another member of an employee involvement team that a lower-level supervisor heads, the person might experience ____________. (a) role underload (b) role overload (c) status incongruence (d) the diversity-consensus dilemma

The team effectiveness equation states: team effectiveness = _____________ + (process gains − process losses). (a) nature of setting (b) nature of task (c) quality of inputs (d) available rewards.

In what ways are teams good for organizations?

What types of formal teams are found in organizations today?

What is the difference between required and emergent behaviors in group dynamics?

What are members of self-managing teams typically expected to do?

One of your Facebook friends has posted this note. "Help! I have just been assigned to head a new product design team at my company. The division manager has high expectations for the team and me, but I have been a technical design engineer for four years since graduating from college. I have never 'managed' anyone, let alone led a team. The manager keeps talking about her confidence that I will be very good at creating lots of teamwork. Does anyone out there have any tips to help me master this challenge? Help!" You smile while reading the message and start immediately to formulate your recommendations. Exactly what message will you send?