Chapter at a glance

Because individuals join organizations for their own reasons and goals, power and politics are inevitable and must be understood. Here's what to look for in Chapter 12. Don't forget to check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

WHAT ARE POWER AND INFLUENCE?

Interdependence, Legitimacy, and Power

Obedience

Acceptance of Authority and the Zone of Indifference

WHAT ARE THE KEY SOURCES OF POWER AND INFLUENCE?

Position Power

Personal Power

Power and Influence Capacity

Relational Influence

WHAT IS EMPOWERMENT?

Keys to Empowerment

Power as an Expanding Pie

From Empowerment to Valuing People

WHAT IS ORGANIZATIONAL POLITICS?

Traditions of Organizational Politics

Politics of Self-Protection

Politics and Governance

An encyclopedia was once written by "experts" and carefully edited. The person in charge had a formal title, and the authors of each entry worked for the publisher. This encyclopedia was expensive to buy and tightly controlled by the publisher. Wikipedia has not only changed this scene, it has represented a new power dynamic. Not only was it free and open for use by all, it was at first totally open to online editing by its users.

"Errors are human ... Openness is the solution not the problem."

The controversial guru of this new wave offering, Jimmy Wales, does not have a formal title such as CEO or president even though he is on the board of directors of the Wikimedia Foundation that runs the Web site. He is the driving force behind an idea he attributes to libertarian economist F. A. Hayek. The idea: When information is dispersed, decisions should be left to those with the most local knowledge. Thus, hundreds of individuals edited Wikipedia entries every day to provide corrections and update the material. They collectively interacted to update Wikipedia in real time. But not all entries were accurate, and this created controversy. According to Wales, "Errors are human ... Openness is the solution not the problem."

Wikipedia's tremendous growth and popularity, as well as even a few hoaxes, have lead Sue Gardner, Wikipedia Foundations' executive director, to institute a number of editorial controls. She also enforces the rule to take "a neutral point of view." Now there are some 1,000 official editors, and it is more difficult to provide a change to existing material. If you want to modify an entry on a current business CEO, for instance, it will be reviewed by a Wikipedia administrator. Wales's original notion of total user control is fading. Wikipedia's current challenge is to keep the excitement of contributions and openness while exerting some power to protect its integrity.

getting things done while you help yourself

What do power and politics have to do with the interaction among individuals, inside or outside of organizations? Plenty. The basis for both power and politics is the degree of interconnectness among individuals.[529] As individuals pursue their own goals within an organization, they must also deal with the interests of other individuals and their desires.[530] There are never enough resources—money, people, time, or authority—to meet everyone's needs. Managers may see a power gap as they constantly face too many competing demands to satisfy. They must choose to favor some interests over others.[531] For example, you may want a flexible schedule in order to achieve a balance between work and home demands but the organization requires you to be present on a regular basis. Your interests and those of the organization do not appear to be consistent. And your manager may not even have the authority to offer you the flexible schedule you need. The managers see a power gap as they recognize that giving you a flexible schedule means others might also ask for one.

The power gap and its associated political dynamics have at least two sides. On the one hand, power and politics can represent the unpleasant side of organizational life. Organizations are not democracies composed of individuals with equal influence. Some people have a lot more power than others. There are winners and losers in the battles for resources and rewards. On the other hand, power and politics are important organizational tools that managers must use to get the job done. More organizational members can "win" when managers identify areas where individual and organizational interests are compatible.

In organizational behavior, power is defined as the ability to get someone to do something you want done or the ability to make things happen in the way you want them to. The essence of power is control over the behavior of others.[532] Without a direct or indirect connection it is not possible to alter the behavior of others.

Power is the ability to get someone else to do something you want done or the ability to make things happen or get things done the way you want.

While power is the force used to make things happen in an intended way, influence is what an individual has when he or she exercises power, and it is expressed by others' behavioral response to the exercise of power. In Chapters 13 and 14 we will examine leadership as a key power mechanism to make things happen. This chapter will discuss other ways that power and politics form the context for leadership influence.

Influence is a behavioral response to the exercise of power.

It is important to remember that the foundation for power rests in interdependence. Each member of an organization's fate is, in part, determined by the actions of all other members. All members of an organization are interdependent. It is apparent that employees are closely connected with the individuals in their work group, those in other departments they work with, and, of course, their supervisors. In today's modern organization the pattern of interdependence and, therefore the base for power and politics, rests on a system of authority and control.[533] Additionally, organizations have societal backing to seek reasonable goals in legitimate ways.

The unstated foundation of legitimacy in most organizations is an understood technical and moral order. From infancy to retirement, individuals in our society are taught to obey "higher authority." In societies, "higher authority" does not always have a bureaucratic or organizational reference but consists of those with moral authority such as tribal chiefs and religious leaders. In most organizations, "higher authority" means those close to the top of the corporate pyramid. The legitimacy of those at the top derives from their positions as representatives for various constituencies. This is a technical or instrumental role. For instance, senior managers may justify their lofty positions by suggesting they represent stockholders. The importance of stockholders is, in turn, a foundation for our capitalistic economic system.

Some senior executives evoke ethics and social causes in their role as authority figures because ethics and social contributions are important foundations for the power of these institutions. For instance, take a look at Leaders on Leadership and Edward J. Zore, President of Northwestern Mutual. Yet, just talking about the ethical and social foundations for power would not be enough to ensure that individuals comply with their supervisor's orders if they were not prone to obedience.

The mythology of American independence and unbridled individualism is so strong we need to spend some time explaining how most of us are really quite obedient. So we turn to the seminal studies of Stanley Milgram on obedience from the early 1960s.[534]

Milgram designed experiments to determine the extent to which people would obey the commands of an authority figure, even if they believed they were endangering the life of another person. Subjects from a wide variety of occupations and ranging in age from 20 to 50 were paid a nominal fee for participation in the project. The subjects were told that the purpose of the study was to determine the effects of punishment on learning. The subjects were to be the "teachers." The "learner," a partner of Milgram's, was strapped to a chair in an adjoining room with an electrode attached to his wrist. The "experimenter," another partner of Milgram's, was dressed in a laboratory coat. Appearing impassive and somewhat stern, the "experimenter" instructed the "teacher" to read a series of word pairs to the learner and then to reread the first word along with four other terms. The learner was supposed to indicate which of the four terms was in the original pair by pressing a switch that caused a light to flash on a response panel in front of the "teacher."

The "teacher" was instructed to administer a shock to the learner each time an incorrect answer was given. This shock was to be increased one level of intensity each time the learner made a mistake. The "teacher" controlled switches that supposedly administered the electric shocks. In reality, there was no electric current in the apparatus. And the "learners" purposely made mistakes often and responded to each shock level in progressively distressing ways. If a "teacher" proved unwilling to administer a shock, the experimenter used the following sequential prods to get him or her to perform as requested. (1) "Please continue"; (2) "The experiment requires that you continue"; (3) "It is absolutely essential that you continue"; and (4) "You have no choice; you must go on." Only when the teacher refused to go on after the fourth prod would the experiment be stopped.

So what happened? Some 65 percent of the "teachers" actually administered an almost lethal shock to the "learners." Shocked at the results, Milgram tried a wide variety of variations (e.g., different commands to continue, a bigger gap between the teacher and the experimenter) with similar if less severe shocks. He concluded that there is a tendency for individuals to comply and be obedient—to switch off their emotions and merely do exactly what they are told to do.

The tendency to obey is powerful and it is a major problem in the corporate boardroom where the lack of dissent due to extreme obedience to authority has been associated with the lack of rationality and questionable ethics.[535]

Obedience is not the only reason for compliance in organizations. The author of groundbreaking research in management theory and organizational studies, Chester Barnard, suggested that it also stemmed from the "consent of the governed."[536] From this notion, Barnard developed the concept of the acceptance of authority—the idea that some directives would naturally be followed while others would not. The basis of this acceptance view was the notion of an implicit contract between the individual and the firm, known as a psychological contract. These two ideas led Barnard to outline the notion of the "zone of indifference" where individuals would comply without much thought.

Acceptance of Authority In everyday organizational life Barnard argued that subordinates accepted or followed a managerial directive only if four circumstances were met.

The subordinate can and must understand the directive.

The subordinate must feel mentally and physically capable of carrying out the directive.

The subordinate must believe that the directive is not inconsistent with the purpose of the organization.

The subordinate must believe that the directive is not inconsistent with his or her personal interests.

Note the way in which the organizational purpose and personal interest requirements are stated. The subordinate does not need to understand how the proposed action will help the organization. He or she only needs to believe that the requested action is not inconsistent with the purpose of the firm. Barnard found the issue of personal interest to be more complicated and he built his analysis on the notion of a psychological contract between the individual and the firm.

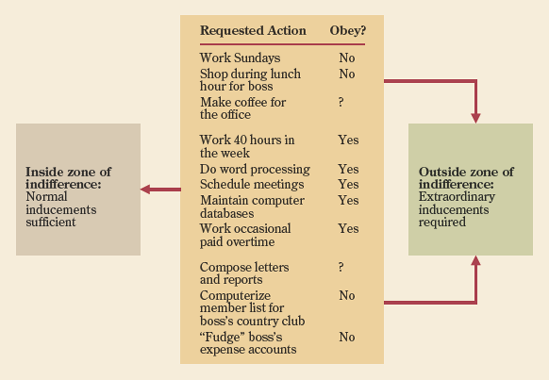

Zone of Indifference Most people seek a balance between what they put into an organization (contributions) and what they get from an organization in return (inducements). Within the boundaries of this psychological contract, therefore, employees will agree to do many things in and for the organization because they think they should. In exchange for the inducements, they recognize the authority of the organization and its managers to direct their behavior in certain ways. Outside of the psychological contract's boundaries, however, things become much less clear.

The psychological contract is an unwritten set of expectations about a person's exchange of inducements and contributions with an organization.

The notion of the psychological contract turns out to be a powerful concept, particularly in the "breach" where an individual feels the contract has been violated. When employees believe the organization has not delivered on its implicit promises, in addition to disobedience, there is less loyalty, higher turnover intentions, and less job satisfaction.[537]

Based on his acceptance view of authority, Chester Barnard calls the area in which authoritative directions are obeyed the zone of indifference. It describes the range of requests to which a person is willing to respond without subjecting the directives to critical evaluation or judgment. Directives falling within the zone are obeyed routinely. Requests or orders falling outside the zone of indifference are not considered legitimate under terms of the psychological contract. Such "extraordinary" directives may or may not be obeyed. This link between the zone of indifference and the psychological contract is shown in Figure 12.1.

The zone of indifference is not fixed. There may be times when a boss would like a subordinate to do things that fall outside of the zone. In this case, the manager must enlarge the zone to accommodate additional behaviors. We have chosen to highlight a number of ethical issues that are within, or may be beyond, the typical zone of indifference. Research on ethical managerial behavior shows that supervisors can become sources of pressure for subordinates to do such things as support incorrect viewpoints, sign false documents, overlook the supervisor's wrongdoing, and conduct business with the supervisor's friends.[539]

Most of us will face such ethical dilemmas during our careers. There are no firm answers to these issues as they are cases of individual judgment. We realize that saying "No" or "refusing to keep quiet" can be difficult and potentially costly. We also realize that you might be willing to do some things for one boss but not another. In different terms, the boss has two sources of power: power position derived from his or her position in the firm, and personal power derived from the individual actions of the manager.[540]

Within each organization a manager's power is determined by his or her position and personal power, his or her individual actions, and the ability to build upon combinations of these sources.

One important source of power available to a manager stems solely from his or her position in the organization. Specifically, position power stems from the formal hierarchy or authority vested in a particular role. There are six important aspects of position power: legitimate, reward, coercive, process, information, and representative power.[541]

Based on our discussion of obedience and the acceptance theory of authority it is easy to understand legitimate power, or formal hierarchical authority. It stems from the extent to which a manager can use subordinates' internalized values or beliefs that the "boss" has a "right of command" to control their behavior. For example, the boss may have the formal authority to approve or deny such employee requests as job transfers, equipment purchases, personal time off, or overtime work. Legitimate power represents the unique power a manager has because subordinates believe it is legitimate for a person occupying the managerial position to have the right to command. If this legitimacy is lost, authority will not be accepted by subordinates.

Legitimate power or formal authority is the extent to which a manager can use the "right of command" to control other people.

Reward power is the extent to which a manager can use extrinsic and intrinsic rewards to control other people. Examples of such rewards include money, promotions, compliments, or enriched jobs. Although all managers have some access to rewards, success in accessing and utilizing rewards to achieve influence varies according to the skills of the manager. While giving rewards may appear ethical, it is not always the case. The use of incentives by unscrupulous managers can be unethical. Check the Ethics in OB for some guidelines.

Reward power is the extent to which a manager can use extrinsic and intrinsic rewards to control other people.

Power can also be based on punishment instead of reward. For example, a manager may threaten to withhold a pay raise or to transfer, demote, or even recommend the firing of a subordinate who does not act as desired. Such coercive power is the extent to which a manager can deny desired rewards or administer punishments to control other people. The availability of coercive power also varies from one organization and manager to another. The presence of unions and organizational policies on employee treatment can weaken this power base considerably.

Process power is the control over methods of production and analysis. The source of this power is the placing of the individual in a position to influence how inputs are transformed into outputs for the firm, a department in the firm, or even a small group. Firms often establish process specialists who work with managers to ensure that production is accomplished efficiently and effectively. Closely related to this is control of the analytical processes used to make choices. For example, many organizations have individuals with specialties in financial analysis. They may review proposals from other parts of the firm for investments. Their power derives not from the calculation itself, but from the assignment to determine the analytical procedures used to judge the proposals.

Process power is the control over methods of production and analysis.

Process power may be separated from legitimate hierarchical power simply because of the complexity of the firm's operations. A manager may have the formal hierarchical authority to make a decision but may be required to use the analytical schemes of others or to consult on effective implementation with process specialists. The issue of position power can get quite complex very quickly in sophisticated operations. This leads us to another related aspect of position power—the role of access to and control of information.

Information power is the access information or the control of it. It is one of the most important aspects of legitimacy. The "right to know" and use information can be, and often is, conferred on a position holder. Thus, information power may complement legitimate hierarchical power. Information power may also be granted to specialists and managers who are in the middle of the information systems in the firm.

For example, the chief information officer of the firm may not only control all the computers, but may also have access to any and all information desired. Managers jealously guard the formal "right to know," because it means they are in a position to influence events, not merely react to them. Most chief executive officers believe they have the right to know about everything in "their" firm. Deeper in the organization, managers often protect information from others based on the notion that outsiders would not understand it. Engineering drawings, for example, are not typically allowed outside of the engineering department. In other instances, information is to be protected from outsiders. Marketing and advertising plans may be labeled "top secret." In most cases the nominal reason for controlling information is to protect the firm. The real reason is often to allow information holders the opportunity to increase their power.

Representative power is the formal right conferred to an individual by the firm enabling him or her to speak as a representative for a group comprised of individuals from across departments or outside the firm. In most complex organizations there is a wide variety of different constituencies that may have an important impact on the firm's operations and its success. They include such groups as investors, customers, alliance partners, and, of course, unions.

Astute executives often hire individuals to act as representatives to ensure that their influence is felt but does not dominate. An example would be an investor relations manager who is expected to deal with the mundane inquiries of small investors, anticipate the questions of financial analysts, and represent the sentiment of investors to senior management. The investor relations manager may be asked to anticipate investors' questions and guide senior managers' responses. The influence of the investor relations manager is, in part, based on the assignment to represent the interests of this particular group.

Personal power resides in the individual and is independent of that individual's position within an organization. Personal power is important in many well-managed firms, as managers need to supplement the power of their formal positions. Four bases of personal power are expertise, rational persuasion, reference, and coalitions.[542]

Expert power is the ability to control another person's behavior through the possession of knowledge, experience, or judgment that the other person does not have but needs. A subordinate obeys a supervisor possessing expert power because the latter usually knows more about what is to be done or how it is to be done than does the subordinate. Expert power is relative, not absolute. So if you are the best cook in the kitchen, you have expert power until a real chef enters. Then the chef has the expert power.

Expert power is the ability to control another's behavior because of the possession of knowledge, experience, or judgment that the other person does not have but needs.

Rational persuasion is the ability to control another's behavior because, through the individual's efforts, the person accepts the desirability of an offered goal and a reasonable way of achieving it. Much of what a supervisor does on a day-to-day basis involves rational persuasion up, down, and across the organization. Rational persuasion involves both explaining the desirability of expected outcomes and showing how specific actions will achieve these outcomes. Relational persuasion relies on trust. OB Savvy 12.1 provides tips to building trust, the key to developing personal power.

Rational persuasion is the ability to control another's behavior because, through the individual's efforts, the person accepts the desirability of an offered goal and a reasonable way of achieving it.

Referent power is the ability to control another's behavior because the person wants to identify with the power source. In this case, a subordinate obeys the manager because he or she wants to behave, perceive, or believe as the manager does. This obedience may occur, for example, because the subordinate likes the boss personally and therefore tries to do things the way the boss wants them done. In a sense, the subordinate attempts to avoid doing anything that would interfere with the boss-subordinate relationship.

Referent power is the ability to control another's behavior because of the individual's desire to identify with the power source.

A person's referent power can be enhanced when the individual taps into the morals held by another or shows a clearer long-term path to a morally desirable end. Individuals with the ability to tap into these more esoteric aspects of corporate life have "charisma" and "vision." Followership is not based on what the subordinate will get for specific actions or specific levels of performance, but on what the individual represents—a role model and a path to a morally desired future. For example, an employee can increase his or her referent power by showing subordinates how they can develop better relations with each other and how they can serve the greater good.

Coalition power is the ability to control another's behavior indirectly because the individual has an obligation to someone as part of a larger collective interest. Coalitions are often built around issues of common interest.[543] To build a coalition, individuals negotiate trade-offs in order to arrive at a common position. Individuals may also trade across issues in granting support for one another. These trade-offs and trades represent informational obligations of support. To maintain the coalition, individuals may be asked to support a position on an issue and act in accordance with the desires of the supervisor. When they do, there is a reciprocal obligation to support them on their issues. For example, members of a department should support a budget increase.

These reciprocal obligations can extend to a network of individuals as well. A network of mutual support provides a powerful collective front to protect members and to accomplish shared interests. Think about all of the required courses you must take to graduate; the list was probably developed by a coalition of professors led by their department chairs. Faculty members who support a required course from another department expect help from the supported department in getting their course on the list.

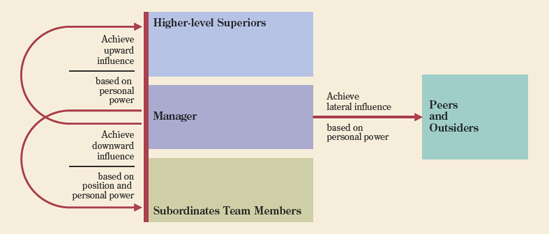

A considerable portion of any manager's time is directed toward what is called power-oriented behavior. Power-oriented behavior is action directed primarily at developing or using relationships in which other people are willing to defer to one's wishes.[544] Figure 12.2 shows three basic dimensions of power and influence affecting a manager and include downward, upward, and lateral dimensions. Also shown in the figure are the uses of personal and position power. The effective manager is one who succeeds in building and maintaining high levels of both position and personal power over time. Only then is sufficient power of the right types available when the manager needs to exercise influence on downward, lateral, and upward dimensions.

Power-oriented behavior is action directed primarily at developing or using relationships in which other people are willing to defer to one's wishes.

Building Position Power Position power can be enhanced when a manager is able to demonstrate to others that their work unit is highly relevant to organizational goals, called centrality, and is able to respond to urgent organizational need, called criticality. Managers may seek to acquire a more central role in the workflow by having information filtered through them, making at least part of their job responsibilities unique, and expanding their network of communication contacts.

A manager may also attempt to increase task relevance to add criticality. There are many ways to do this. The manager may try to become an internal co-ordinator within the firm or an external representative. When the firm is in a dynamic setting of changing technology, the executive may also move to provide unique services and information to other units. A manager may shift the emphasis on his or her group's activities toward emerging issues central to the organization's top priorities. To effectively initiate new ideas and new projects may not be possible unless a manager also delegates more routine activities and expands both the task variety and task novelty for subordinates. Of course, not all attempts to build influence may be positive. Some managers are known to have defined tasks so they are difficult to evaluate by creating an ambiguous job description or developing a unique language for their work.

Building Personal Power Personal power arises from the individual characteristics of the manager. Three personal characteristics—expertise, political savvy, and likeability—have potential for enhancing personal power in an organization. The most obvious is building expertise. Additional expertise may be gained by advanced training and education, participation in professional associations, and involvement in the early stages of projects.

A somewhat less obvious way to increase personal power is to learn political savvy—better ways to negotiate, persuade individuals, and understand the goals and means they are most willing to accept. The novice believes that most individuals are very much the same: they acknowledge the same goals, and will accept similar paths toward these goals. The more astute individual recognizes important individual differences among coworkers. The most experienced managers are adept at building coalitions and developing a network of reciprocal obligations.

Finally, a manager's personal power is increased by characteristics that enhance his or her likeability and create personal appeal in relationships with other people. These include pleasant personality traits, agreeable behavior patterns, and attractive appearance. See Mastering Management for tips on how to bring these factors together.

Building Influence Capacity One of the ways people build influence capacity is by taking steps to increase their visibilities in the organization. This is done by (1) expanding the number of contacts they have with senior people, (2) making oral presentations of written work, (3) participating in problem-solving task forces, (4) sending out notices of accomplishments, and (5) seeking additional opportunities to increase personal name recognition.[545] Most managers also recognize that, between superiors and subordinates, access to or control over information is an important element.

Another way of building influence capacity is by controlling access to information. A manager may appear to expand his or her expert power over a subordinate by not allowing the individual access to critical information. Although the denial may appear to enhance the boss's expert power, it may reduce the subordinate's effectiveness. In a similar manner, a supervisor may also control access to key organizational decision makers. An individual's ability to contact key persons informally can offset some of this disadvantage. Furthermore, astute senior executives routinely develop "back channels" to lower-level individuals deep within the firm to offset the tendency of bosses to control information and access.

Expert power is often relational and embedded within the organizational context. Many important decisions are made outside formal channels and are substantially influenced by key individuals with the requisite knowledge. By developing and using coalitions and networks, an individual may build on his or her expert power. And through coalitions and networks, an individual may alter the flow of information and the context for analysis. By developing coalitions and networks, executives also expand their access to information and their opportunities for participation.

Managers can also build influence capacity by controlling, or at least attempting to control, decision premises. A decision premise is a basis for defining the problem and selecting among alternatives. By defining a problem in a manner that fits the executive's expertise, it is natural for that executive to be in charge of solving it. Thus, the executive subtly shifts his or her position power. Executives who want to increase their power often make their goals and needs clear and bargain effectively to show that their preferred goals and needs are best. They do not show their power base directly but instead provide clear "rational persuasion" for their preferences. So the astute executive does not threaten or attempt to invoke sanctions to build power. Instead, he or she combines personal power with the position of the unit to enhance total power. As the organizational context changes, different personal sources of power may become more important alone and in combination with the individual's position power. There is an art to building power.

Using position and personal power successfully to achieve the desired influence over other people is a challenge for most managers. Practically speaking, there are many useful ways of exercising relational influence. The most common techniques involve the following:[546]

- Reason:

Using facts and data to support a logical argument.

- Friendliness:

Using flattery, goodwill, and favorable impressions.

- Coalition:

Using relationships with other people for support.

- Bargaining:

Using the exchange of benefits as a basis for negotiation.

- Assertiveness:

Using a direct and forceful personal approach.

- Higher authority:

Gaining higher-level support for one's requests.

- Sanctions:

Using organizationally derived rewards and punishments.

Research on these strategies suggests that reason is the most popular technique overall.[547] Friendliness, assertiveness, bargaining, and higher authority are used more frequently to influence subordinates than to influence supervisors. This pattern of attempted influence is consistent with our earlier contention that downward influence generally includes mobilization of both position and personal power sources, whereas upward influence is more likely to draw on personal power.

Truly effective managers, as suggested earlier in Figure 12.2, are able to influence their bosses as well as their subordinates. One study reports that both supervisors and subordinates view reason, or the logical presentation of ideas, as the most frequently used strategy of upward influence.[548] When queried on reasons for success and failure, however, the two groups show similarities and differences in their viewpoints. The perceived causes of success in upward influence are very similar for both supervisors and subordinates and involve the favorable content of the influence attempt, a favorable manner of its presentation, and the competence of the subordinate.[549]

There is, however, some disagreement between the two groups on the causes of failure. Subordinates attribute failure in upward influence to the closed-mindedness of the supervisor, and unfavorable and difficult relationship with the supervisor, as well as the content of the influence attempt. Supervisors also attribute failure to the unfavorable content of the attempt, but report additional causes of failure as the unfavorable manner in which it was presented, and the subordinate's lack of competence.

Empowerment is the process by which managers help others to acquire and use the power needed to make decisions affecting themselves and their work. More than ever before, managers in progressive organizations are expected to be good at and comfortable with empowering the people with whom they work. Rather than considering power to be something to be held only at higher levels in the traditional "pyramid" of organizations, this view considers power to be something that can be shared by everyone working in flatter and more collegial structures.[550]

Empowerment is the process by which managers help others to acquire and use the power needed to make decisions affecting themselves and their work.

The concept of empowerment is part of the sweeping change taking place in today's corporations. Corporate staff is being cut back; layers of management are being eliminated; and the number of employees is being reduced as the volume of work increases. What is left is a leaner and trimmer organization staffed by fewer managers who must share more power as they go about their daily tasks. Indeed, empowerment is a key foundation of the increasingly popular self-managing work teams and other creative worker involvement groups. While empowerment has been popular and successfully implemented in the United States and Europe for over a decade, new evidence suggests it can boost performance and commitment in firms worldwide, as well.[551]

One of the bases for empowerment is a radically different view of power itself. So far, our discussion has focused on power that is exerted over other individuals. In this traditional view, power is relational in terms of individuals. In contrast, the concept of empowerment emphasizes the ability to make things happen. Power is still relational, but in terms of problems and opportunities, not just individuals. Cutting through all of the corporate rhetoric on empowerment is quite difficult, because the term has become quite fashionable in management circles. Each individual empowerment attempt needs to be examined in light of how power in the organization will be changed.

Changing Position Power When an organization attempts to move power down the hierarchy, it must also alter the existing pattern of position power. Changing this pattern raises some important questions. Can "empowered" individuals give rewards and sanctions based on task accomplishment? Has their new right to act been legitimized with formal authority? All too often, attempts at empowerment disrupt well-established patterns of position power and threaten middle- and lower-level managers. As one supervisor said, "All this empowerment stuff sounds great for top management. They don't have to run around trying to get the necessary clearances to implement the suggestions from my group. They never gave me the authority to make the changes, only the new job of asking for permission."

Expanding the Zone of Indifference When embarking on an empowerment program, management needs to recognize the current zone of indifference and systematically move to expand it. All too often, management assumes that its directive for empowerment will be followed because management sees empowerment as a better way to manage. Management needs to show precisely how empowerment will benefit the individuals involved and provide the inducement needed to expand the zone of indifference.

Along with empowerment, employees need to be trained to expand their power and their new influence potential. This is the most difficult task for managers and a challenge for employees, for it often changes the dynamic between supervisors and subordinates. The key is to change the concept of power within the organization from a view that stresses power over others to one that emphasizes the use of power to get things done. Under the new definition of power, all employees can be more powerful and the chances of success can be enhanced.

A clearer definition of roles and responsibilities may help managers to empower others. For instance, senior managers may choose to concentrate on long-term, large-scale adjustments to a variety of challenging and strategic forces in the external environment. If top management tends to concentrate on the long term and downplay quarterly mileposts, others throughout the organization must be ready and willing to make critical operating decisions to maintain current profitability. By providing opportunities for creative problem solving coupled with the discretion to act, real empowerment increases the total power available in an organization. In other words, the top levels don't have to give up power in order for the lower levels to gain it. Note that senior managers must give up the illusion of control—the false belief that they can direct the actions of employees even when the latter are five or six levels of management below them.

The same basic arguments hold true in any manager-subordinate relationship. Empowerment means that all managers need to emphasize different ways of exercising influence. Appeals to higher authority and sanctions need to be replaced by appeals to reason. Friendliness must replace coercion, and bargaining must replace orders for compliance. Given the all too familiar history of an emphasis on coercion and compliance within firms, special support may be needed for individuals so that they become comfortable in developing their own power over events and activities. For instance, one recent study found that management's efforts at increasing empowerment in order to boost performance was successful only when directly supported by individual supervision. Without leader support there is no increase in empowerment and, therefore, less improvement in performance.[552]

What executives fear, and all too often find, is that employees passively resist empowerment by seeking directives they can obey or reject. The fault lies with the executives and the middle managers who need to rethink their definition of power and reconsider the use of traditional position and personal power sources. The key is to lead, not push; reward, not sanction; build, not destroy; and expand, not shrink. To expand the zone of indifference also calls for expanding the inducements for thinking and acting, not just for obeying.

Beyond empowering employees, a number of organizational behavior scholars argue that U.S. firms need to change how they view employees in order to sustain a competitive advantage in an increasingly global economy.[553] While no one firm may have all of the necessary characteristics, Jeffrey Pfeffer suggests that the goals of the firm should include placing employees at the center of their strategy. To do so they need to:

develop employment security for a selectively recruited workforce;

pay high wages with incentive pay and provide potential for employee ownership;

encourage information sharing and participation with an emphasis on self-managed teams;

emphasize training and skill development by utilizing talent and cross-training; and

pursue egalitarianism (at least symbolically) with little pay compression across units and enable extensive internal promotion.

Of course, this also calls for taking a long-term view coupled with a systematic emphasis on measuring what works and what does not, as well as a supporting managerial philosophy. This is a long list. However, it appears consistent with sentiments of John Chambers, CEO of Cisco, and his emphasis on people and interconnections.

Any study of power and influence inevitably leads to the subject of "politics." For many, this word may conjure up thoughts of illicit deals, favors, and advantageous personal relationships. Perhaps this image of shrewd, often dishonest, practices of obtaining one's way is reinforced by Machiavelli's classic fifteenth-century work, The Prince, which outlines how to obtain and hold power by way of political action. For Machiavelli, the ends justified the means. It is important, however, to understand the importance of organizational politics and adopt a perspective that allows work place politics to function in a much broader capacity.[554]

There are two different traditions in the analysis of organizational politics. One tradition builds on Machiavelli's philosophy and defines politics in terms of self-interest and the use of nonsanctioned means. In this tradition, organizational politics may be formally defined as the management of influence to obtain ends not sanctioned by the organization or to obtain sanctioned ends by way of non-sanctioned influence.[555] Managers are often considered political when they seek their own goals, use means that are not currently authorized by the organization or those that push legal limits. Where there is uncertainty or ambiguity, it is often extremely difficult to tell whether or not a manager is being political in this self-serving sense.[556] For example, to earn a bonus, some mortgage brokers often neglected to verify the income of mortgage applicants. It was not illegal but it certainly was self-serving and could be labeled political.

The second tradition treats politics as a necessary function resulting from differences in the self-interests of individuals. Here, organizational politics is viewed as the art of creative compromise among competing interests. Under this view, the firm is more than just an instrument for accomplishing a task or a mere collection of individuals with a common goal. It acknowledges that the interests of individuals, stakeholders, and society must also be considered.

Organizational politics is the management of influence to obtain ends not sanctioned by the organization or to obtain sanctioned ends through nonsanctioned means and the art of creative compromise among competing interests.

In a heterogeneous society, individuals will disagree as to whose self-interests are most valuable and whose concerns should therefore be bounded by collective interests. Politics arise because individuals need to develop compromises, avoid confrontation, and live and work together. This is especially true in organizations, where individuals join, work, and stay together because their self-interests are served. Furthermore, it is important to remember that the goals of the organization and the acceptable means of achieving them are established by powerful individuals in the organization in their negotiation with others. Thus, organizational politics is also the use of power to develop socially acceptable ends and means that balance individual and collective interests.

Political Interpretation The two different traditions of organizational politics are reflected in the ways executives describe the effects on managers and their organizations. In one survey, some 53 percent of those interviewed indicated that organizational politics enhanced the achievement of organizational goals and survival. Yet some 44 percent also suggested that politics distracted individuals from organizational goals.[557]

Organizational politics is not inherently good or bad. It can serve a number of important functions, including overcoming personnel inadequacies, coping with change, and substituting for formal authority. Even in the best-managed firms, mismatches arise among managers who are learning, are burned out, lack necessary training and skills, are overqualified, or are lacking the resources needed to accomplish their assigned duties. Organizational politics provides a mechanism for circumventing these inadequacies and getting the job done. It can also facilitate adaptation to changes in the environment and technology of an organization.

Organizational politics can also help identify problems and move ambitious, problem-solving managers into action. It is quicker than restructuring and allows the firm to meet unanticipated problems with people and resources quickly, before small headaches become major problems. Finally, when a person's formal authority breaks down or fails to apply to a particular situation, political actions can be used to prevent a loss of influence. Managers may use political behavior to maintain operations and to achieve task continuity in circumstances where the failure of formal authority may otherwise cause problems. And as shown in OB Savvy 12.2, political skill has even been linked to lowering executive stress.

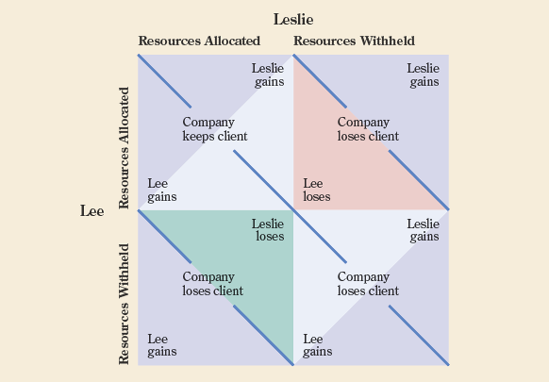

Political Forecasting Managers may gain a better understanding of political behavior in order to forecast future actions by placing themselves in the positions of other persons involved in critical decisions or events. Each action and decision can be seen as having benefits for and costs to all parties concerned. Where the costs exceed the benefits, the manager may act to protect his or her position. Figure 12.3 shows a sample payoff table for two managers, Lee and Leslie, in a problem situation involving a decision as to whether or not they should allocate resources to a special project.

If both managers authorize the resources, the project gets completed on time and their company keeps a valuable client. Unfortunately, if they do this, both Lee and Leslie spend more than they have in their budgets. Taken on its own, a budget overrun would be bad for the managers' performance records. Assume that the overruns are acceptable only if the client is kept. Thus, if both managers act, both they and the company win, as depicted in the upper-left block of the figure. Obviously, this is the most desirable outcome for all parties concerned.

Assume that Leslie acts, but Lee does not. In this case, the company loses the client, Leslie overspends the budget in a futile effort, but Lee ends up within budget. While the company and Leslie lose, Lee wins. This scenario is illustrated in the lower-left block of the figure. The upper-right block shows the reverse situation, where Lee acts but Leslie does not. In this case, Leslie wins, while the company and Lee lose. Finally, if both Lee and Leslie fail to act, each stays within the budget and therefore gains, but the company loses the client.

The company clearly wants both Lee and Leslie to act. But will they? Would you take the risk of overspending the budget, knowing that your colleague may refuse to do the same? The question of trust is critical here, but building trust among co-managers and other workers can be difficult and takes time. The involvement of higher-level managers may be needed to set the stage. Yet in many organizations both Lee and Leslie would fail to act because the "climate" or "culture" too often encourages people to maximize their self-interest at minimal risk.

Subunit Power To be effective in political action, managers should also understand the politics of subunit relations.[558] Units that directly contribute to organizational goals are typically more powerful than units that provide advice or assistance. Units toward the top of the hierarchy are often more powerful than are those toward the bottom. More subtle power relationships are found among units at or near the same level in a firm. Political action links managers more formally to one another as representatives of their work units.

Five of the more typical lateral, intergroup relations a manager may engage with are workflow, service, advisory, auditing, and approval.[559] Workflow linkages involve contacts with units that precede or follow in a sequential production chain. Service ties involve contacts with units established to help with problems. For instance, an assembly-line manager may develop a service link by asking the maintenance manager to fix an important piece of equipment on a priority basis. In contrast, advisory connections involve formal staff units having special expertise, such as a manager seeking the advice of the personnel department on evaluating subordinates.

Auditing linkages involve units that have the right to evaluate the actions of others after action has been taken, whereas approval linkages involve units whose approval must be obtained before action may be taken. In general, units gain power as more of their relations with others are of the approval and auditing types. Workflow relations are more powerful than are advisory associations, and both are more powerful than service relations.

While organizational politics may be helpful to the organization as a whole, it is more commonly known and better understood in terms of self-protection.[560] Whether or not management likes it, all employees recognize that in any organization they must first watch out for themselves. In too many organizations, if the employee doesn't protect himself or herself, no one else will. Individuals can employ three common strategies to protect themselves. They can (1) avoid action and risk taking, (2) redirect accountability and responsibility, or (3) defend their turf.

Avoidance Avoidance is quite common in controversial areas where the employee must risk being wrong or where actions may yield a sanction. Perhaps the most common reaction is to "work to the rules." That is, employees are protected when they adhere strictly to all the rules, policies, and procedures and do not allow deviations or exceptions. Perhaps one of the most frustrating but effective techniques is to "play dumb." We all do this at some time or another. When was the last time you said, "Officer, I didn't know the speed limit was 35. I couldn't have been going 52 miles an hour."

Although working to the rules and playing dumb are common techniques, experienced employees often practice somewhat more subtle techniques of self-protection. These include depersonalization and stalling. Depersonalization involves treating individuals, such as customers, clients, or subordinates, as numbers, things, or objects. Senior managers don't fire long-term employees; the organization is merely "downsized" or "delayered." Routine stalling involves slowing down the pace of work to expand the task so that the individuals look as if they are working hard. With creative stalling, the employees may spend the time supporting the organization's ideology, position, or program and delaying implementation of changes they consider undesirable.

Redirecting Responsibility Politically sensitive individuals will always protect themselves from accepting blame for the negative consequences of their actions. Again, a variety of well-worn techniques may be used for redirecting responsibility. "Passing the buck" is a common method employees and managers use. The trick here is to define the task in such a way that it becomes someone else's formal responsibility. The ingenious ways in which individuals can redefine an issue to avoid action and transfer responsibility are often amazing.

Both employees and managers may avoid responsibility by bluffing or rigorous documentation. Here, individuals take action only when all the paperwork is in place and it is clear that they are merely following procedure. Closely related to rigorous documentation is the "blind memo," or blind e-mail, which explains an objection to an action implemented by the individual. Here, the required action is taken, but the blind memo or e-mail is prepared should the action come into question. Politicians are particularly good at this technique. They will meet with a lobbyist and then send a memo to the files confirming the meeting. Any relationship between what was discussed in the meeting and the memo is "accidental."

As the last example suggests, a convenient method some managers use to avoid responsibility is merely to rewrite history. If a program is successful, the manager claims to have been an early supporter. If a program fails, the manager was the one who expressed serious reservations in the first place. Whereas a memo in the files is often nice to have in order to show one's early support or objections, some executives don't bother with such niceties. They merely start a meeting by recapping what has happened in such a way that makes them look good.

For the truly devious, there are three other techniques for redirecting responsibility. One technique is to blame the problem on someone or some group that has difficulty defending itself. Fired employees, outsiders, and opponents are often targets of such scapegoating. Closely related to scapegoating is blaming the problem on uncontrollable events.[561] The astute manager goes far beyond this natural tendency to place the blame on events that are out of their control. A perennial favorite is, "Given the unexpected severe decline in the overall economy, firm profitability was only somewhat below reasonable expectations." Meaning, the firm lost a bundle of money.

Should these techniques fail, there is always another possibility: facing apparent defeat, the manager can escalate commitment to a losing cause of action. That is, when all appears lost, assert your confidence in the original action, blame the problems on not spending enough money to implement the plan fully, and embark on actions that call for increased effort. The hope is that you will be promoted, have a new job with another firm, or be retired by the time the negative consequences are recognized. It is called "skating fast over thin ice."[562]

Defending Turf Defending turf is a time-honored tradition in most large organizations. As noted earlier in the chapter, managers seeking to improve their power attempt to expand the jobs their groups perform. Defending turf also results from the coalitional nature of organizations. That is, the organization may be seen as a collection of competing interests held by various departments and groups. As each group attempts to expand its influence, it starts to encroach on the activities of other groups. Turf protection is common in organizations and runs from the very lowest position to the executive suite.

When you see these actions by others, the question of ethical behavior should immediately come to mind. Check the Ethics in OB to make sure you are not using organizational politics to justify unethical behavior.

From the time of the robber barons such as Jay Gould in the 1890s, Americans have been fascinated with the politics of the chief executive suite. Recent accounts of alleged and proven criminal actions emanating from the executive suites of Washington Mutual, Bear Stearns, WorldCom, Enron, Global Crossings, and Tyco have caused the media spotlight to penetrate the mysterious veil shrouding politics at the top of organizations.[563] An analytical view of executive suite dynamics may lift some of the mystery.

Agency Theory An essential power problem in today's modern corporation arises from the separation of owners and managers. A body of work called agency theory suggests that public corporations can function effectively even though their managers are self-interested and do not automatically bear the full consequences of their managerial actions. The theory argues that (1) all the interests of society are served by protecting stockholder interests, (2) stockholders have a clear interest in greater returns, and (3) managers are self-interested and unwilling to sacrifice these self-interests for others (particularly stockholders) and thus must be controlled. The term agency theory stems from the notion that managers are "agents" of the owners.[564]

So what types of controls should be instituted? There are several. One type of control involves making sure that what is good for stockholders is good for management. Incentives in the pay plan for executives may be adjusted to align with the interests of management and stockholders. For example, executives may get most of their pay based on the stock price of the firm via stock options. A second type of control involves the establishment of a strong, independent board of directors, since the board is to represent the stockholders. While this may sound unusual, it is not uncommon for a CEO to pick a majority of the board members and to place many top managers on the board. A third way is for stockholders with a large stake in the firm to take an active role on the board. For instance, mutual fund managers have been encouraged to become more active in monitoring management. And there is, of course, the so-called market for corporate control. For instance, poorly performing executives can be replaced by outsiders.[565]

The problem with the simple application of all of these control mechanisms is that they do not appear to work very well even for the stockholders and clearly, some suggest, not for others either. For example, the recent challenges faced by General Motors were met by a very passive Board of Directors. The compensation of the CEO increased even when the market share of the firm declined. Many board members were appointed at the suggestion of the old CEO and only a few board members held large amounts of GM stock.

Recent studies strongly suggest that agency-based controls backfire when applied to CEOs. One study found that when options were used extensively to reward CEOs for short-term increases in the stock price, it prompted executives to make risky bets. The results were extreme with big winners and big losers. In a related investigation the extensive use of stock options was associated with manipulation of earnings when these options were not going to give the CEOs a big bonus. These researchers concluded that "stock-based managerial incentives lead to incentive misalignment."[566]

The recent storm of controversy over CEO pay and the studies cited above illustrate questions for using a simple application of agency theory to control executives. Until the turn of the century, U.S. CEOs made about 25 to 30 times the pay of the average worker. This was similar to CEO pay scales in Europe and Japan. Today, however, many U.S. CEOs are paid 300 times the average salary of workers.[567] Why are they paid so much? It is executive compensation specialists who suggest these levels to the board of directors. The compensation specialists list the salaries of the top paid, most successful executives as the basis for suggesting a plan for a client CEO. The board or the compensation committee of the board, selected by the current CEO and consisting mainly of other CEOs, then must decide if the firm's CEO is one of the best. If not one of the best then why should they continue the tenure of the CEO? Of course, if the candidate CEO gets a big package it also means that the base for subsequent comparison is increased. And round it goes.

It is little wonder that there is renewed interest in how U.S. firms are governed. Rather than proposing some quick fix based on a limited theory of the firm, it is important to come to a better understanding of different views on the politics of the executive suite. By taking a broader view, you can better understand politics in the modern corporation.

Resource Dependencies Executive behavior can sometimes be explained in terms of resource dependencies—the firm's need for resources that are controlled by others.[568] Essentially, the resource dependence of an organization increases as (1) needed resources become more scarce, (2) outsiders have more control over needed resources, and (3) there are fewer substitutes for a particular type of resource controlled by a limited number of outsiders. Thus, one political role of the chief executive is to develop workable compromises among the competing resource dependencies facing the organization—compromises that enhance the executive's power.

To create executive-enhancing compromises, managers need to diagnose the relative power of outsiders and to craft strategies that respond differently to various external resource suppliers. For larger organizations, many strategies may center on altering the firm's degree of resource dependence. Through mergers and acquisitions, a firm may bring key resources within its control. By changing the "rules of the game," a firm may also find protection from particularly powerful outsiders. For instance, before being absorbed by another firm, Netscape sought relief from the onslaught of Microsoft by appealing to the U.S. government. Markets may also be protected by trade barriers, or labor unions may be put in check by "right to work" laws. Yet there are limits on the ability of even our largest and most powerful organizations to control all important external contingencies.

International competition has narrowed the range of options for chief executives and they can no longer ignore the rest of the world. For instance, once U.S. firms could go it alone without the assistance of foreign corporations. Now, chief executives are increasingly leading companies in the direction of more joint ventures and strategic alliances with foreign partners from around the globe. Such "combinations" provide access to scarce resources and technologies among partners, as well as new markets and shared production costs.[569]

Organizational Governance With some knowledge of agency theory and resource dependencies it is much easier to understand the notion of organizational governance. Organizational governance refers to the pattern of authority, influence, and acceptable managerial behavior established at the top of the organization. This system establishes what is important, how issues will be defined, who should and should not be involved in key choices, and the boundaries for acceptable implementation. Students of organizational governance suggest that a "dominant coalition" comprised of powerful organizational actors is a key to understanding a firm's governance.[570]

Organizational governance is the pattern of authority, influence, and acceptable managerial behavior established at the top of the organization.

Although one expects many top officers within the organization to be members of this coalition, the dominant coalition occasionally includes outsiders with access to key resources. Thus, analysis of organizational governance builds on the resource dependence perspective by highlighting the effective control of key resources by members of a dominant coalition. It also recognizes the relative power of key constituencies, such as the power of stockholders stressed in agency theory. Recent research suggests that some U.S. corporations are responding to stakeholder and agency pressures in the composition of their boards of directors.43

This dependence view of the executive suite recognizes that the daily practice of organizational governance is the development and resolution of issues. Through the governance system, the dominant coalition attempts to define reality. By accepting or rejecting proposals from subordinates, by directing questions toward the interests of powerful outsiders, and by selecting individuals who appear to espouse particular values and qualities, the pattern of governance is slowly established within the organization. Furthermore, this pattern rests, at least in part, on political foundations.

While organizational governance was an internal and a rather private matter in the past, it is now becoming more public and controversial. Some argue that senior managers don't represent shareholder interests well enough, as we noted in the discussion of agency theory. Others are concerned that managers give too little attention to broader constituencies. We think managers should recognize the basis for their power and legitimacy and become leaders. The next two chapters are devoted to the crucial topic of leadership.

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 12.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 12 study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

What are power and influence?

Power is the ability to get someone else to do what you want him or her to do.

Power vested in managerial positions derives from three sources: rewards, punishments, and legitimacy or formal authority.

Influence is what you have when you exercise power.

Position power is formal authority based on the manager's position in the hierarchy.

Personal power is based on one's expertise and referent capabilities.

Managers can pursue various ways of acquiring both position and personal power.

Managers can also become skilled at using various techniques—such as reason, friendliness, and bargaining—to influence superiors, peers, and subordinates.

What are the key sources of power and influence?

Individuals are socialized to accept power, the potential to control the behavior of others, and formal authority, the potential to exert such control through the legitimacy of a managerial position.

The Milgram experiments illustrate that people have a tendency to obey directives that come from others who appear powerful and authoritative.

Power and authority work only if the individual "accepts" them as legitimate.

The zone of indifference defines the boundaries within which people in organizations let others influence their behavior.

What is empowerment?

Empowerment is the process through which managers help others acquire and use the power needed to make decisions that affect themselves and their work.

Clear delegation of authority, integrated planning, and the involvement of senior management are all important to implementing empowerment.

Empowerment emphasizes power as the ability to get things done rather than the ability to get others to do what you want.

What is organizational politics?

Politics involves the use of power to obtain ends not officially sanctioned as well as the use of power to find ways of balancing individual and collective interests in otherwise difficult circumstances.

For the manager, politics often occurs in decision situations where the interests of another manager or individual must be reconciled with one's own.

For managers, politics also involves subunits that jockey for power and advantageous positions vis-à-vis one another.

The politics of self-protection involves efforts to avoid accountability, redirect responsibility, and defend one's turf.

While some suggest that executives are agents of the owners, politics also comes into play as resource dependencies with external environmental elements that must be strategically managed.

Organizational governance is the pattern of authority, influence, and acceptable managerial behavior established at the top of the organization.

CEOs and managers can develop an ethical organizational governance system that is free from rationalizations.

Agency theory (p. 297)

Coalition power (p. 285)

Coercive power (p. 283)

Empowerment (p. 289)

Expert power (p. 285)

Influence (p. 278)

Information power (p. 284)

Legitimate power (p. 282)

Organizational governance (p. 299)

Organizational politics (p. 292)

Political savvy (p. 287)

Power (p. 278)

Power-oriented behavior (p. 286)

Process power (p. 284)

Psychological contract (p. 281)

Reward power (p. 283)

Rational persuasion (p. 285)

Referent power (p. 285)

Representative power (p. 284)

Zone of indifference (p. 281)

Three bases of position power are ____________. (a) reward, expertise, and coercive power (b) legitimate, experience, and judgment power (c) knowledge, experience, and judgment power (d) reward, coercive, and knowledge power

____________ is the ability to control another's behavior because, through the individual's efforts, the person accepts the desirability of an offered goal and a reasonable way of achieving it. (a) Rational persuasion (b) Legitimate power (c) Coercive power (d) Charismatic power

A worker who behaves in a certain manner to ensure an effective boss-subordinate relationship shows ____________ power. (a) expert (b) reward (c) approval (d) referent

One guideline for implementing a successful empowerment strategy is that ____________. (a) delegation of authority should be left ambiguous and open to individual interpretation (b) planning should be separated according to the level of empowerment (c) it can be assumed that any empowering directives from management will be automatically followed (d) the authority delegated to lower levels should be clear and precise

The major lesson of the Milgram experiments is that ____________. (a) Americans are very independent and unwilling to obey (b) individuals are willing to obey as long as it does not hurt another person (c) individuals will obey an authority figure even if it does appear to hurt someone else (d) individuals will always obey an authority figure

The range of authoritative requests to which a subordinate is willing to respond without subjecting the directives to critical evaluation or judgment is called the ____________. (a) psychological contract (b) zone of indifference (c) Milgram experiments (d) functional level of organizational politics

The three basic power relationships to ensure success are ____________. (a) upward, downward, and lateral (b) upward, downward, and oblique (c) downward, lateral, and oblique (d) downward, lateral, and external

In which dimension of power and influence would a manager find the use of both position power and personal power most advantageous? (a) upward (b) lateral (c) downward (d) workflow

Reason, coalition, bargaining, and assertiveness are strategies for ____________. (a) enhancing personal power (b) enhancing position power (c) exercising referent power (d) exercising influence

Negotiating the interpretation of a union contract is an example of ____________. (a) organizational politics (b) lateral relations (c) an approval relationship (d) an auditing linkage

____________ is the ability to control another's behavior because of the possession of knowledge, experience, or judgment that the other person does not have but needs. (a) Coercive power (b) Expert power (c) Information power (d) Representative power

A ___________ is the range of authoritative requests to which a subordinate is willing to respond without subjecting the directives to critical evaluation or judgment. (a) A zone of indifference (b) Legitimate authority (c) Power (d) Politics

The process by which managers help others to acquire and use the power needed to make decisions affecting themselves and their work is called ______________. (a) politics (b) managerial philosophy (c) authority (d) empowerment

The pattern of authority, influence, and acceptable managerial behavior established at the top of the organization is called ______________. (a) organizational governance (b) agency linkage (c) power (d) politics

__________ suggests that public corporations can function effectively even though their managers are self-interested and do not automatically bear the full consequences of their managerial actions. (a) Power theory (b) Managerial philosophy (c) Virtual theory (d) Agency theory

Explain how the various bases of position and personal power do or do not apply to the classroom relationship between instructor and student. What sources of power do students have over their instructors?

Identify and explain at least three guidelines for the acquisition of (a) position power and (b) personal power by managers.

Identify and explain at least four strategies of managerial influence. Give examples of how each strategy may or may not work when exercising influence (a) downward and (b) upward in organizations.

Define organizational politics and give an example of how it operates in both functional and dysfunctional ways.