4

Recording

4.1 Responsibilities

All the equipment, bells, whistles and toys are of no use whatsoever unless there is something worthwhile to record – something your listeners will want to hear. Acquiring that material is the first task.

At the more complex level, you may be editing something that has been put together in a studio, or maybe a recording of a live event. In the context of this book, this means that the recording has already been done; you are presented with a stereo mix on analogue tape, a DAT or even a multitrack mix on an eight-track video cassette-based digital multitrack. These days it may even be on a removable hard disk.

If you have a suitable sound card, then you may be making the original recording using Cool Edit. In practice, most people, most of the time, are using something external to originate material. It may be off-air from radio, from a CD or any number of delivery formats (see section 5.5, Recording).

Your first responsibility is to ensure that you can handle the delivery format. An eight-track ADAT tape is fine only if you have an ADAT machine and your computer is set up to record its tracks, either by analogue or using the optical ADAT eight-track digital interface.

Even with DAT, you should have specified the sampling rate you require. This should normally be the rate you intend to use for the final edited version: 44.1 kHz for compact disc-related work, or maybe 48 kHz for material destined to be broadcast. Do not use lower sampling rates, or bit rates lower than 16, even if material is destined as a reduced data Internet sound file. You never know when there will be another use for the audio, and the better the input to a poor reproduction system, the better it will sound.

However, much of the material put together with a PC audio editor is likely to be less ambitious, and self-acquired; probably using a portable recorder, preferably digital, with an ability to transfer digitally to your computer.

A common way of obtaining your material is the interview; so here are a few guidelines to get the best out of it. These guidelines are as applicable to the promotional sales interview with the chairman of the company, as for a news interview for local or national radio.

4.2 Interviewing people

Preparation

Editing starts here, so consider the following so as not to waste your own or other people’s time and resources:

- What is the purpose of the interview? Are you interviewing the right person? (Do they have the information you want? Do they have a reasonable speaking voice?) Remember that the boss’s deputy or assistant often has a better finger on the pulse of day-to-day problems, so it can be useful to interview both, if you can.

- Prepare your subject area for questions, rather than a long list of specific questions.

- Choose a suitable and convenient location. A senior manager’s office is usually suitable, if it has a carpet and soft furnishings; but it is extremely important to get the person out from behind the desk. While you will tell interviewees that acoustics is the reason, it is equally vital to be aware that people speak differently across desks. Sitting beside them on a sofa will usually get a much more human response.

Types of interviews

- Hard interviews are performed to expose reasoning and to let listeners make up their own minds. The interviewee comes in cold, with no knowledge of the questions. Hard interviews are commonly used with politicians or those in the public eye.

- Informational interviews are for getting as much information as possible, so these are likely to be a more friendly, conversational style of interview. You may prepare your interviewee with a warm-up by outlining the areas of questioning.

- Personality interviews are intended to reveal the personality of the interviewee.

- Emotional interviews are probably the most difficult type of interview, requiring the greatest tact and diplomacy from the interviewer. Such interviews are of the ‘How do you feel?’ variety used when interviewees may be under great stress following a tragedy, (although try to avoid the actual question ‘How do you feel . . .?’).

Technique

Make sure that you actually know how to use the recorder! Try it out before the day of the interview, and test the recorder before you leave base. Test it when you arrive and are waiting for your interviewee. Test it when you take level. Always keep the test recordings.

Always record useful information, such as the date and who you are going to interview. This will help speed the identification of a recording when the label has fallen off and when it has been transferred to computer (some DAT and Minidisc machines will record a time of day and date code on the recording. This can be useful, provided you remembered to set the clock when you took the machine out of its box).

NEVER say anything rude about the person or company. ‘I’m off to interview that prat Smith of that useless Bloggo company’ might get you a laugh in the office, but loses its edge when you find yourself accidentally playing it back to Mr Smith after he has given you level. Machines that only offer headphone monitoring are a help here, but spill from headphones can be very audible.

If using a handheld microphone, then sit or stand close to the person being interviewed. Again, get the interviewee out from behind the desk! Side by side on a sofa usually works very well. The microphone should be 20–30 cm from each of you; if you have to compromise, favour the interviewee.

Make a short test recording ‘for level’. The nominal task is to set the recording level so that it does not distort or is so low in level as to cause noise problems when amplified for use. For level, do not ask a question that is going to be asked during the interview. Traditionally, interviewers were supposed to ask what their interviewee had for breakfast. These days it is likely to produce either a monosyllabic ‘nothing’, or a long and involved account of some special muesli. No, this is the opportunity to record the interviewee’s name and title. Get the interviewee to say it, and use this as a way of checking the level on the recorder. As well as giving you a factual check – is the interviewee Assistant Manager or Deputy Manager? – it gives you a definitive pronunciation of his or her name; is Mr Smyth pronounced Sm-ith or Sm-eyeth? In some styles of documentary this can be used for interviewees to introduce themselves rather than the presenter doing it.

It is good practice to leave the level set from your previous test recording, so that the level is roughly right if you run in to a major news story on your way to or from the interview and need to ‘crash start’ a recording.

Another function of the level test is check for unnoticed problems. An air-conditioning noise that you do not notice ‘live’ may be very obtrusive on playback. Listen for, and anticipate, external noises – e.g. children playing, dogs barking, telephones ringing, interruptions.

There can also be unexpected electrical interference. Faulty fluorescent tubes can cause interference, as can radio and computer equipment. Beware especially of mobile ‘phones. As well as the obvious annoyance of them ringing during an interview, audio equipment is very prone to interference from the mobile’s acoustically silent ‘handshake’ signals with the network. Switch off your own mobile and ask your interviewee to do the same.

Relax the interviewee, if necessary, by discussing areas of questioning.

Keep eye contact, and make appropriate silent responses such as nodding or smiling. Ask short, clear questions, one at a time. Remember, we want to hear the interviewee not the interviewer.

Listen carefully, and keep your questions relevant to what is being said. Ask open questions – who, what, where, why, how? BBC Radio Four’s first The World at One presenter, William Hardcastle, maintained that he added to this list the non-alliterative ‘Is it on the increase?’.

Pre-recorded interviews

When pre-recording an interview, record the background atmosphere for 15–30 seconds before and after the interview to use when editing. In my experience, leaving a 2-second gap between ‘Right, we’re recording’ and the first question will give you the cleanest pause.

If you are using two microphones with a stereo recorder, then deliberately record the interview ‘two-track’ so that the interviewee’s voice is on one track and the interviewer’s is on the other. Keep to a convention so that questions are always on the same track – ‘the presenter is always right’ was the tongue-in-cheek convention used in BBC Radio. In the days of quarter-inch tape, this also had the advantage that the answers could be heard on an old half-track mono machine that only read the top (left-hand channel) of the tape.

After the interview, play back the last few seconds to ensure that the piece has recorded OK. Ask if the interviewee feels that anything was left out.

Vox pop interviews

In the trade, interviews with people randomly selected in the street are known as vox pops (from the Latin vox populi; voice of the people). They present their own unique problems.

Always test the equipment before leaving base. Follow a closed question (e.g. ‘Do you think. . .?’) with an open question (e.g. ‘Why do you think that?) to get interviewees to justify their opinions. Prepare several forms of the same question to put to interviewees.

Choose a suitable location away from traffic, road works, etc. (unless, perhaps, the item is about the traffic or the chaos caused by the road works). Approach interviewees with a brief explanation of why you’re conducting a survey of public opinion. Keep the recording level the same and adjust the microphone position for quieter or louder interviewees. Record background actuality at the beginning and end of the tape.

(A comprehensive guide to interviewing is contained in Robert McLeish’s Radio Production – A Manual for Broadcasters, 4th edition, published by Focal Press, 1999.)

4.3 Documentary

Documentary material will also use ‘actuality’. This is material recorded on location, of activity, that can be used both for illustration and for bridging passages of time. Record lots of it! It is too easy to be so closely focused on the interview material that the non-vocal material is forgotten. Do not be in the situation of the producer who recorded a feature about a mountain climbing expedition and forgot to record any sounds of people climbing! (In this particular case the situation was saved by a single 2-second sequence being looped, repeated and used in a stylized way.)

Actuality is different from sound effects. Actuality is the real thing, recorded at the actual location. Sound effects come from a library and are used to fake actuality. This is fine for drama, but has only limited use in factual items. Using an FX disc of a Rolls Royce driving off would be fine as an illustration of a car driven by rich people, but not ethical if cued as ‘Joe Smith driving off in his Rolls Royce after my interview’.

Music can enhance an item, but beware of copyright and performance rights. While the sound of a busker playing in the background is unlikely to be a problem, using a complete performance of a piece of music usually is.

4.4 Oral history interviews

In oral history interviews you are interviewing someone, usually an elderly person, about memories of decades before. This is possibly the first and only time the interviewee has been interviewed, and you want the person to be relaxed and speak freely. You need to be relaxed too, as these interviews are likely to be long. Sitting side by side on a sofa can work, but some people are unhappy about sitting so close to a stranger. Here, I have used a tip from Charles Parker who, with the Radio Ballads, pioneered British documentary radio. He suggested actually sitting or kneeling at the interviewee’s feet. This has the effect of lowering your perceived status and emphasizes that the interviewee’s memories and views are important. With one knee on the floor, the other becomes a convenient place to rest the elbow of the arm holding the microphone. Acoustically it is good because the microphone naturally falls about 45 cm from both you and the interviewee, with both bodies providing sound absorption.

4.5 Interviews on the move

Interviews on the move are perhaps not so much interviews as two or more people reacting to an environment – for example, observing badgers at night, a historical house or a carnival. The object is to capture as much of the atmosphere as possible while not making it totally impossible to edit.

In some ways, an ideal medium is a four-track recording. Two tracks can be fed from a stereo microphone to record atmosphere, and the other two by two mono microphones, one for the presenter – possibly a personal ‘tie-clip’ mic – and the other (handheld) for whoever else is talking from moment to moment. An alternative might be two small portables – Minidisc or DAT – one recording atmosphere and the other recording dialogue.

The major disadvantage of such an arrangement is that the technology is in danger of taking over. The person holding the mics and carrying the recorders may be employed for his or her knowledge of the subject, rather than technical skill. Here, a separate recorder operated by the producer can help out with collecting actuality.

It is very possible to get a dramatic and memorable recording using a single handheld stereo mic, but it is vital that the mic is not much moved about with respect to the speakers, as otherwise their voices will go careering around the sound stage. In noisy environments the mic should be as close as is feasible to the voices in order to get as much separation as possible, so that what is being said can be understood. Plenty of actuality should be obtained for dubbing over the edited speech. It is easy to add sound, but it is difficult or impossible to take it away. A sensible discipline is also required so that the unrepeatable sounds of an event are not spoken over, and a commentary is given that is articulate and will not need editing.

When editing a feature about, say, an outdoor market, the buzz of its activity is vital. While some material may be recorded in shops away from the noise of the market, probably the best material, editorially, will be acquired in the crowd. A beat pause before each question (or response) from the presenter is all that is needed to form the basis of a crossfade on atmosphere to a different section. Where the edit causes an abrupt change of character of the background, then a short section of separately recorded actuality can be added to cover the change (see section 9.5, Chequerboarding).

4.6 Recorders

The original portable acquisition format was direct-cut Edison cylinders. Later, 78-rpm lacquer discs were used by reporters during the Second World War. They were heavy – more transportable than portable – and could not be used ‘over the shoulder’. With the perfection of tape recording by the Germans during that war, the 1940s and 1950s saw the rapid appearance of more and more useful portable tape recorders.

Tape (like disc) had the advantage that the recording medium was the same as the editing medium, which was the same as the final user or transmission medium. Removable digital media have the potential to be the same. However, at the time of writing, recorders using this sort of technology tend to be bulky and heavy and there is no agreed standard. Recorders are becoming available that use small hard disks with sufficient capacity not to need to compress the audio. They are either removable or can download their recordings via a USB or Firewire port, and download times of 40 times real time are achievable. The only disadvantage is that the recorder has to be brought back to the computer at base, or it has to have removable media such as a hard disk that plugs in to a PCM-1A socket with a suitable port being provided on the base computer.

Small recorders using Minidisc or DAT are very attractive. Ordinary domestic recorders can produce superb quality at prices a fraction those of professional gear. Also becoming readily available are recorders using memory cards. A problem with these, as well as Minidisc, is that they usually use ‘lossy’ data compression techniques. This can cause problems if the edited recordings are further going to be data compressed, especially using different systems. This is a hazard that especially faces broadcasters. If this is important to you, then use DAT but beware of its fragility and dislike of humid conditions. Although cheap, the trade-off is that domestic recorders use fragile domestic plugs and sockets. This is not a problem if your environment allows you to take care of the machine, or is sufficiently well financed to regard them as disposable.

Alternatively, an option is to purchase a case designed to protect the recorder. These make the whole package larger, but they have professional XLR sockets and also a high-capacity battery for longer recording times. There is also the incidental (but not inconsequential) effect of making the reporter look more ‘professional’. This can make the difference between being granted an interview, or rejection. There are professional versions of both DAT and Minidisc recorders. These have XLR sockets, and are generally more robust than their domestic brethren.

Whatever and wherever you are recording, you need to get the best out of your microphone, and a basic review of acoustics and microphones may be helpful.

4.7 Acoustics and microphones

Acoustics

When making a recording, realize that the microphone will pick up sounds other than the ones you really want. So what does a microphone hear?

- The voice or instrument in front of it

- Reflections from the wall

- Noise from outside the room

- Other sounds in the room, including voices and instruments

- General noises, if outdoors.

Separation

Much of the skill in getting a decent recording is to arrange good separation between the wanted and the unwanted sounds. The classic ways of improving this are:

- Multi-mics

- Booths/separate studios

- Multitrack recording

- Working with the microphone closer

- Using directional microphones.

Multi-mics

There are many ways of reducing the spill of unwanted sound while retaining the wanted. It can seem that the answer to most problems is to have as many microphones as possible, but in fact the opposite is true. If you have six microphones faded up, each microphone will ‘hear’ one direct sound from the sound source it is set to pick up. However, it, and the other five mics, will also get the indirect sound from its own sound source and every other sound source.

In my example, you will be getting six lots of indirect sound for every single direct sound. As a result, multi-mic balances are very susceptible to picking up a great deal of studio acoustic.

With discussions, a lot of mics very close together on a single table can provide extra control and give some stereo positioning. Avoid the temptation to seat contributors to such discussions in a circle with comfy chairs, coffee tables and individual stand mics. The resulting acoustic quality will be excellent; but unfortunately the discussion is likely to be boring and stilted. This is because once you go beyond a critical distance of about 120 cm, people stop having conversations and start to make statements.

A studio designed for multi-mic music recording will have a relatively ‘dead’ acoustic, with reflections much reduced. The disadvantage of this is that the musicians and singers cannot hear themselves properly. In a very dead studio, a singer can go hoarse in minutes! You have to substitute for the lack of acoustic by feeding an artificial one to headphones worn by the artist. Needless to say, such a studio would be a disaster for a discussion.

Booths/separate studios

Booths/separate studios give good separation, but with the penalty of isolating the performers from one another.

Multitrack recording

Laying down one track at a time while listening to the rest on headphones gives good separation, but it can be difficult to realize a sense of the excitement of performance.

Working with the microphone closer

When you work with the microphone closer, the direct sound becomes louder and so you can turn down the fader and therefore apparently reduce the amount of indirect sound from that microphone. This has the disadvantage that the microphone is much more sensitive to movement by the artist and other unwanted noises can become a problem – guitar finger noise is clearly audible, breathing becomes exaggerated, and spittle and denture noises can become offensive.

It is a matter of opinion just how much breathing and action noise is desirable; eliminate these noises totally and it no longer sounds like human beings playing the music, but if there is too much it becomes irritating.

Using directional microphones

Microphones are not particularly directional, and are likely to have angles of pickup of 30–45° away from the front.

High directivity mics will give poor results with an undisciplined performer who moves about a lot. The main value of directional microphones is not the angles at which they are sensitive, but the angles where they are dead. It is more critical to position a microphone so that its dead angle rejects the sound from another source. Here, a few degrees of adjustment can make a lot of difference to the rejection and no audible difference to the sound you actually want.

Orchestral music

Classical and orchestral music tends to be performed in a room or hall with a decent acoustic with a relatively small number of microphones – typically a main stereo mic plus some supplementary mics to fill in the sound of soloists, etc. Not only will the musicians be happier – many non-electric instruments are hard to play if wearing headphones – but also the larger number of musicians involved often makes it impractical to find that number of working headphones, let alone connect them all up and ensure that they are all producing the right sound, at safe levels.

Microphones

There is no such thing as the perfect microphone; a single mic that will be best for all purposes. While expense can be a guide, there are circumstances in which a cheaper microphone might be better.

There is often a conflict between robustness and quality. As a rule, electrostatic microphones provide better quality. They have much lighter diaphragms that can respond quickly to the attack transients at the start of sounds, better frequency responses, and lower noise figures. However, they are not particularly robust. They can be very prone to blasting and popping, especially on speech, where a moving coil microphone can be a better choice. Electrostatic microphones are reliant on some form of power supply, which will either come from a battery within the mic or from a central power supply providing ‘phantom volts’ down the mic lead. These can fail at inconvenient times.

Quality

Yes, of course we want quality, but what do we mean by this? We want a mic that can collect the sound without distortion, popping, hissing or spluttering. With speech, there is a premium on intelligibility that is only loosely connected with how ‘hi-fi’ the mic is. An expensive mic that is superb on orchestral strings may be a popping and blasting disaster as a speech mic.

Directivity

Directional microphones are described by their directivity pattern. This can be thought of as tracing the path of a sound source round the microphone – the source being moved nearer or further away so that the mic always hears the same level. At the dead angle the source has to be very close to the mic, and at the front it can be further away.

Beware that sound picked up around the dead angles of a microphone can sound drainpipe-like and can have a different characteristic from that at the front.

As a rule, the more directional a microphone is, the more sensitive it is to wind noise and ‘popping’ on speech. When used out of doors, heavy wind shielding is essential. Film and television crews usually use a very directional ‘gun’ mic with a pickup angle of about 20° either side of centre. These are invariably used with a windshield – the large furry ‘sausage’ often seen pointing at public figures in news conferences.

The most common directivity mic is the cardioid (Figure 4.1), so called because of its heart-shaped directivity pattern. Cardioid microphones have a useful dead angle at the back. Placing this to reduce spill is more important than ensuring that it is pointing directly at the sound it is picking up.

A so-called hypercardioid mic is slightly more directional (not more heart-shaped!) (Figure 4.2). It has the disadvantage that it has a small lobe of sensitivity at the back and is dead at about 10° either side of the back of the microphone. However, when used for interviews using table stands the dead angle is usually about right for rejecting other people around the table.

Another common type of microphone is called omnidirectional, as it is sensitive equally in all directions (Figure 4.3). Omnidirectional microphones are particularly suitable for outdoor use, as they are much less sensitive to wind noise and blasting. They can be better for very close working, where directivity is not important, as they pop or blast less easily – an important consideration with speech and singing.

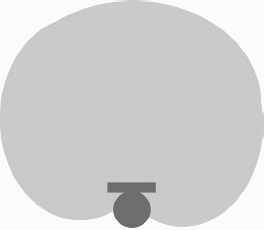

Barrier mics (PZMs) can produce good results with little visibility as a result of being attached to an existing object (Figure 4.4). This can be anything from the stage at an opera to a goal post on a football field. They work best when attached to a large surface such as a wall, floor, table or baffle, and can be slung over stages using transparent sheet plastic as the baffle material to reduce visibility. The resulting pickup pattern is hemispherical; an omnidirectional pattern ‘cut in half’ (Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5 Hemispherical pick-up pattern

A more specialist directivity pattern is the figure-of-eight (Figure 4.6). This microphone is dead top and bottom and at the sides, but ‘live’ front and back. This directivity pattern is most often found in variable-pattern microphones. Figure-of-eight mics can give the best directional separation provided that they can be placed so that the back lobe does not receive any spill, or can be used to pick up sound as well. Ribbon mics have the very best of dead angles and can be very useful when miking an audience that is also being fed sound from loudspeakers.

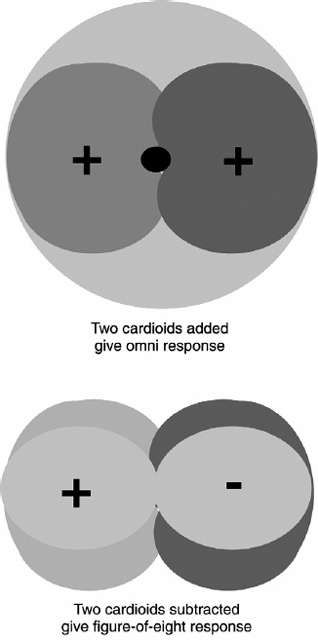

Variable pattern mics

These (usually very expensive) microphones offer nine or so patterns. They work by actually containing two cardioids back to back (Figure 4.7).

If only one cardioid is switched on then, as you would expect, the mic behaves as a cardioid. If both cardioids are switched on and their outputs are added together, then an omnidirectional response is obtained. If they are both switched on and their outputs subtracted, then a figure-of-eight pattern results.

The other intermediate patterns are obtained by varying the relative sensitivities of the two cardioids.

Beware; these derived patterns are never as good as the same pattern produced by a fixed pattern mic. The cardioids retain their physical characteristics, so an omni mic pattern derived from the two cardioids does not have the resistance to wind noise and blasting of a dedicated omni mic. The dead angle rejection or a derived figure-of-eight is not as good as a ribbon. Most microphones are ‘end fire’ – you point them at the sound you want. These mics are ‘side-fire’ with their sensitive angles coming out of the side of the mic.

Figure 4.7 Variable pattern microphone using back-to-back cardioids

Transducers

A microphone is a type of transducer – a device that converts one form of energy into another. In this case, acoustic energy is converted into electrical. Most microphones fall into one of two categories: electromagnetic or electrostatic.

Electromagnetic mics

Most electromagnetic microphones are moving coil. They are often called dynamic mics. They are like miniature loudspeakers in reverse; the acoustic energy moves a diaphragm attached to which is a coil of wire surrounded by a magnet (Figure 4.8). This causes a small audio voltage to be generated.

Figure 4.8 Moving coil electromagnetic microphone

A specialized form of electromagnetic mic is the ‘ribbon’ mic, which once was very widely used by the BBC. These have an inherent figure-of-eight directivity. They consist of a heavy magnet and a thin corrugated ‘ribbon’ of aluminium, which moves in the magnetic field to generate the audio voltage. They are ‘side fire’ mics.

Electrostatic mics

Electrostatic mics, also known as capacitor or condenser microphones, fall into two types. Many require a polarizing voltage of about 50 V for them to work. This is not a problem in a studio that can provide the necessary power as ‘phantom’ volts down the mic cable. Some mics contain 9-V batteries that operate a voltage boost circuit to provide their own polarizing voltage.

Electrostatic mics work by making the diaphragm part of a capacitor. A capacitor consists of two plates of metal placed very close together, and when a voltage is applied a current flows momentarily and the plate acts as a store for this charge. This is due to the attraction between positive and negative electricity across the narrow gap. If the plates are moved closer together, then this attraction increases and the plates can store more charge. If they are moved apart, then the attraction reduces and the amount of charge that can be stored is reduced. The consequence of the plate distance changing is a current through the circuit.

If one of the plates is the capsule of a microphone and the other is the diaphragm, made of a very thin film of conductive plastic, then we have the basis of a high quality microphone. The very lightness of the diaphragm gives it the ability to follow high frequencies much better than the relatively heavy assembly of a moving-coil microphone. As the diaphragm moves out, so the storage of the capacitor is reduced and charge is forced outwards. As the diaphragm moves inwards, the storage increases and the current flows in the opposite direction as the capacitor is ‘filled up’ by the polarizing voltage.

However, particularly for battery-operated mics, an ‘electret’ diaphragm can be used. This does not need the polarizing voltage, as a static charge is ‘locked’ into the diaphragm at manufacture. It is the electrostatic equivalent of a permanent magnet. While the technology is much improved, these tend to deteriorate with age.

There is a variant on the electrostatic mic where the capacitor, that is the diaphragm, is part of a radio frequency oscillator circuit. The changing capacitance changes the frequency of the oscillation, producing a frequency-modulated signal that is converted into audio within the microphone. RF capacitor mics have a good reputation for standing up to hostile environments, and are frequently seen as ‘gun’ mics used by film and TV sound recordists.

Other considerations

Robustness

Is the mic likely to be dropped, blown on, driven over? Does it blast on speech or singing?

Environment

Are you indoors or outdoors? Is the mic going to get wet or blown upon? Non-directional (omnidirectional) mics are least prone to wind noise, and this can be further improved by a decent windshield. In practice, using your own body to block the wind can be the most effective method of reducing wind noise.

Moving-coil (dynamic) microphones are the most resistant to problems caused by moisture or rain. Umbrellas are of little help in rain because of the noise of the rain falling on them! The windshield is usually enough to prevent rain from getting into the mic. If you ever need to record under water or in a shower, then a practical protection is a condom.

Size and weight

Presenters and singers do not like carrying heavy mics. Mics slung above people must be well secured by two fixings, each of which is capable of preventing the mic falling onto the audience or artists.

Visibility

This is affected by the size and weight of the microphone, and also its colour. Television producers of classical music programmes want minimum visibility. This may be helped by using small mics that are painted ‘television grey’.

Operas on stage are often miked by six or so PZM/barrier mics laid on the stage and isolated from stage thumps by a layer of foam plastic (stage mice).

Power requirement

Total reliance on phantom power fed down the mic cable can mean losing everything if the power supply goes down. Batteries fail unpredictably. (Even if you thought you just put a new one in; in the stress of a session, it is easy to put the old one back in. Get into the habit of scratching a mark on the old battery before taking the new one out of the wrapper). Unpowered electromagnetic mics have definite advantages here.

Reliability, consistency and ‘pedigree’

Microphones made by reputable manufacturers and bought through recognized dealers are likely to be more reliable and long lasting than an unknown make bought through a dodgy outlet. They are also likely to be consistent in quality, so one XYZ model mic sounds just like another model XYZ mic.

4.8 Multitrack

While most computers are equipped with single stereo sound cards, it is equally possible to fit cards that can handle more than two channels at a time. The main use for these is in music recording, but they can also be useful for speech, drama and documentary. However, multitrack is very intensive in its use of data. To state the obvious, a CDR with 80 minutes’ capacity of stereo will only have room for 20 minutes of eight-track audio.

Many multichannel systems have quality benefits even if you rarely need multitrack recording. They use ‘break-out’ boxes so the critical audio components are outside the hostile environment of the computer. These boxes can be placed conveniently on the desk, while the computer can be floor standing.

If a long recording run is not required, then Minidisc, hard disk or even tape cassette-based multitrack recorders can be an option. There are also video cassette-based eight-track systems, which can provide about 40 minutes’ continuous running.

While there may be a temptation to record a discussion multitrack with a view to pulling out extracts for a programme, in practice it is quicker (and cheaper) to have the discussion mixed straight down to stereo by an experienced sound balancer. You also save by not having to allocate time for mixing down the material from multitrack to mono or stereo.