Chapter 6

Discovery–Attractiveness of the Business Opportunity1

Let's go back to Insight 7 from Chapter 3 (that not everyone is good at this, you need the right people on board), and tell the story of Dylan and Frank.

Both were highly skilled analysts on my Nortel Business Ventures Group (BVG) team. They were early in their careers, ambitious, and diamonds in the rough that I knew would require my coaching to help them uncover their potential. They were part of the initial core team, and we developed our approach to innovation together. Dylan is an engineer, with an MBA, and Frank has his MBA, with a finance specialization. Their role was to screen and evaluate the ideas that were being submitted from Nortel employees to determine where we wanted to place our investment dollars. In the first few months, there was pent-up demand. A few teams came forward that had already been working on business opportunities, so we had to evaluate the merits of their proposals. We invested in two of these within our first few months, which took considerable time. We also had made a request for proposals from Nortel employees, so we also had to screen their submissions, most of which were simply raw, underdeveloped ideas, not investment opportunities. With the involvement of others on the team, Dylan and Frank screened out a few hundred ideas in the first year.

After about a year and a half of investing in promising Nortel technologies and business models, I received a call from our president of advanced technology, Gedas Sakus. A very disgruntled employee was not pleased that Frank had rejected his idea, and I was asked to look into it. So I spoke with Frank and he explained all the reasons for his rejection of the idea. On the surface, he applied very sound logic on the basis of appropriate assumptions, and yet my instincts told me I was missing something. I decided to ask a little more to get impressions from others on our team and was wondering why Dylan had not run into a similar situation.

What emerged reinforced Insight 3 that there is a lot more to Discovery than evaluating ideas and Insight 7 that not everyone is suited for certain innovation roles. Discovery is about the world of possibilities, not probabilities, where divergent thinking is required to conceive of how ideas can be shaped into opportunities. Frank, with his finance background, lives in the world of probabilities that can be factored into an economic model. He would shut down ideas, often prematurely, before the innovation group could get a better sense of their potential, because possibilities cannot be modeled. Dylan's background, in contrast, makes him more suited to the world of possibilities, and he also has the right mind-set for Discovery. In fact, Dylan is one of the best people I have ever seen, along with Hans Brink Hansen at Grundfos and Jamie Nielsen at NOVA Chemicals, for building upon ideas to shape them into opportunities and articulating their value in a way they can be understood.

Once I realized the skill sets required for Discovery were about opportunity elaboration and connecting the dots, not about evaluation, Dylan became our point person for Discovery and Frank's activities were redirected to the evaluation of business opportunities once they were more developed. And guess what? I never heard from Gedas again—at least not on that issue!

I know what you are thinking. Of course, many ideas do need to be screened out early and there are always going to be people not happy that their idea was not chosen, yet even delivering this message requires a finesse that not many people have. The bottom line is that Discovery is much more suited to people with the mind-set of asking questions to look for possibilities, rather than those who look for the reasons why something will not work. This requires working together with the idea originator to shape the opportunity, compared with asking the idea originator to convince me of why I should pay attention to the idea. Often, those with the ideas lack the skills to make the compelling case, which is where the opportunity recognizers, the Dylans, versus the idea evaluators, the Franks, come in. Both are talented, yet one is more suited to Discovery than the other. Think of the two legal systems in the world: one where you are innocent until proven guilty and the other where you are guilty until proven innocent. Which one do you think offers the best potential for a fair hearing? Which mind-set would you rather be facing when coming forward with an early idea? I know which one I would choose. Do you?

Now let's see how this carries through to Discovery, where we Plant a business vision of what could be, not what will be, since we do not know yet…with far too much uncertainty!

Discovery Principles2

Discovery is about the conceptualization of business opportunities that may have a major impact in the marketplace through the delivery of either new performance benefits or greatly improved performance over what already exists. We are often asked which is better—technology push, where the technology drives the innovation, or market pull, based on a clear market need. The answer is that it is not an either-or situation; rather, it requires that the technical and market considerations be addressed in parallel. Often for opportunities fraught with uncertainty, the potential of the technology or the market potential is not clear. The market needs to learn from the technology, and the technology needs to evolve based on what is learned from the market. For this reason, a serial product development or phase gate process does not work, because it does not support this type of iterative learning approach. Once the product is defined, it is developed and then field-tested prior to a full market launch. Discovery is the starting point to define the business concept that will be iteratively tested during Incubation to arrive at a definable product.

Discovery requires unique skills to uncover technical insights, recognize opportunities, and articulate their value. The technical insights come from understanding the underlying science, demonstrating or making assumptions regarding the feasibility of the technology or business model, as well as the evaluation of emerging or competing technologies and a company's intellectual property (IP) position. Opportunity recognition requires skills in external and internal scouting to clarify the potential of opportunities. For opportunity articulation, networking with potential market collaborators or early market adopters is required to identify sources of perceived value and clarify strategic possibilities for the company. This needs to be communicated in a language senior leaders can understand, which is less about the technology and more about the business potential. An important element of describing this business potential is in identifying a list of potential applications to begin investigating to reinforce that there are many strategic options.

Therefore, the four objectives for moving from Discovery to Incubation are to:

It is worth emphasizing that the most promising opportunity from a market perspective does not mean the biggest. We are looking for markets that can benefit the most from the innovation. This is a common mistake in most companies, which tend to be concerned about what the market can do for them in terms of revenue generation, rather than what they can provide the market in terms of benefits.

See Table 6.1 for the Discovery Focus Areas from Table 3.3, Innovation Business Opportunity Evolution, in Chapter 3.

Table 6.1 Discovery Focus Areas

| Plant | Discovery Conceptualization Output = Opportunity Concept |

| Technical Uncertainty Understanding technology drivers, value, and economic feasibility |

Technical Feasibility and Capabilities, IP Landscape Scoping |

| Market Uncertainty Learning about market drivers, value creation, and business viability |

Application Possibilities, Value Proposition, Business Potential, Business Model Options |

| Resource Uncertainty Accessing money, people, and capabilities internally and externally |

Availability of Funding and Right People, Competency Gaps Identification for Partnering Options |

| Organization Uncertainty Gaining and maintaining organizational legitimacy |

Capacity for Innovation, Fit with Strategic Intent, and Senior Level Commitment |

Source: rInnovation Group

Discovery and Open Innovation

Prior to the breaking up of AT&T in 1984, and early in my telecommunications career, the closed corporate labs, such as Bell Labs, were the ones driving the model for innovation. What I mean by closed is that the source of inventions was internal—research and development (R&D) took place inside these labs, performed by the people working there. They did not look outside for inventions. The belief was that we have the best people working here, so why even look outside?

This is not to suggest that these inventions did not spur the growth of other companies. There were cross-licensing agreements that made these discoveries available to outside parties. In fact, many game-changing inventions came from these labs, such as the transistor, the laser, information theory, and C and C++ programming languages, to name a few. They certainly became the catalysts for the information and communications revolution and the early seeds of Silicon Valley. Other labs, such as those at Westinghouse, General Electric, Kodak, DuPont, British Telecom, Bayer, Merck, and so forth, provided the foundation for our twentieth-century infrastructure and our improved way of life. With the rapid adoption of technology, the world is becoming a much smaller place and all great ideas do not exist within the confines of a corporate research and development lab (they never did, yet it was the prevailing model for innovation of the times).

Interestingly, these monolithic, closed labs are actually a twentieth-century phenomenon, brought on by the two world wars, and they most certainly created many inventions and provided homes for inventors to bring their inventions to life. Now, the model for innovation has evolved to resemble how it was before then (forward or back to the past—history does repeat itself) to combine Invention activities from internally focused research and Discovery activities within and outside of the company. Invention is the creation of something from the laboratories that was previously unknown. Discovery, in contrast, is becoming aware of something known in other venues, but not known to the company or a group within the company. The most common model is where outside technologies are brought into a company to improve its Discovery capabilities. Of course, scientists have collaborated within and outside the company as a professional practice, but outside collaboration on a business level did not exist during the closed lab era, unless it was within the Bell family, for example.

The Open Innovation model combines these Invention and Discovery activities to shorten the time to understand a technology's or business model's market value and accelerate commercialization. Procter & Gamble's Connect + Develop open innovation approach is an excellent example, which brought Swiffer cleaning tools to the world through a partnership with a Japanese company.3 Therefore, Discovery does not equal Invention. Invention is to create something new, whereas one can discover phenomena in the world that are used in other capacities, whether they are existing or new. In addition, Discovery does not equal R&D, as described in the story of Dylan and Frank; technical people often come up with the ideas, but need guidance to articulate their potential business and market value.

Today, the business outcomes of Discovery work depend on this Open Innovation model. While open innovation is not a new phenomenon, it is more widely embraced by the business community. Companies are now realizing that there needs to be a healthy balance between leveraging internal and external expertise to develop innovation opportunities.

Discovery Progression: Capturing Innovation Opportunities4

Ideas are only the beginning of the journey to create business value. While idea generation within the context of strategic intent, themes, or innovation portfolios and platforms is essential, the realizable value is in translating these ideas into business opportunities. An opportunity is defined as a match between a need in the marketplace (hidden or explicit) and a product or service offering that fills that need. Increasing the flow of good ideas requires directed idea generation based on strategic drivers and enablers such as think tanks, connection to external sources, and forecasting based on technology and market trends. It is not about serendipitous idea generation. Of course, accidental discoveries do happen, but these are rare. Most often a good idea comes through hard work, rather than a flash of insight, as in the famous quote from Thomas Edison: “Genius is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.”

Opportunity Recognition

Going back to the story of Dylan and Frank: As we learned in our early years at Nortel, it is all about opportunities, and it is not easy to find them. We would all be extremely wealthy if we could do so. Let's go back to my Netscape story from Chapter 3. Imagine in the early days of the Internet around 1994, when I came upon the Mosaic browser and Netscape at this Bellcore meeting. I was working for Stentor, which was the consortium of Canadian telephone companies. I remember specifically Nick Ciancio at Pacific Bell bringing this opportunity to our attention. He said it would revolutionize the Internet by providing a user-friendly interface. It generated a lot of excitement at the meeting, and we all took the opportunity back to our home companies for consideration. As mentioned previously, not only did others not see the potential, but it was viewed more as a minor threat to our long distance business that could potentially displace some international toll traffic. Even though we were responsible for new business opportunities, it was difficult to make the case for why we should invest, especially with this mind-set and our entrenched long distance and data divisions.

This opportunity was shipped off to another group and eventually became the foundation of the Canadian Internet service provider Sympatico. Of course, Nick was right. It did revolutionize the Internet, and hindsight is 20/20. Yet, one can only imagine where the telephone companies would be today if they could have seen that the Internet was much more than displacing high-priced international long distance traffic. Recognizing opportunities is difficult, but articulating them in a way for others to see them is even more of a challenge.

In case you are wondering since it was such a long time ago…the word ‘Internet’ did exist in the early 90s. In fact, according to Wikipedia, the first use of the word internet was in a scientific paper in 1974 as an adjective and, in 1982, it became the noun it is today. Once again, another word, like innovation, that goes back in time and was used in a different context, as early as 1883! Interesting piece of trivia, now back to opportunity recognition.

Learning how to recognize opportunities requires building up skills to gather and scout for ideas that can then be shaped into attractive opportunities. People who are good at this we call opportunity recognizers or innovation catalysts, as we saw in the case of Dylan and Nick, or even me. They typically demonstrate a high level of technical sophistication to understand the potential of the technology, with a worldly market savvy to connect the dots with market needs. These people are often the mavericks in your company. You know who they are. Are you one of them? We push up against the status quo and are motivated to make a difference and stretch the company in new areas. We also know each other and play critical roles in conducting an informal sanity check of an opportunity's potential, within our well-connected internal and external networks.

Once opportunities have been uncovered, an initial evaluation should take place involving team members with senior management credibility, innovation project experience, deep technical expertise, business development experience, and, perhaps, even specialized expertise from outside the company. The initial decision criteria and assumptions should focus on:

- How the technology will unfold.

- How the markets will develop.

- How the company will respond.

It is important to be clear on the assumptions you are making, given the uncertainty of these early opportunities. Often, these assumptions are misinterpreted as facts, only to surface at the most inopportune time in the innovation life cycle to seriously undermine the potential of the business opportunities. This happened to us at Nortel with our NetActive venture. The team came from the residential broadband area and we believed that residential broadband deployment was imminent. Of course, it is standard today, but it was clearly an assumption that we accepted as a fact in the late 1990s. I will elaborate upon this story in Chapter 10.

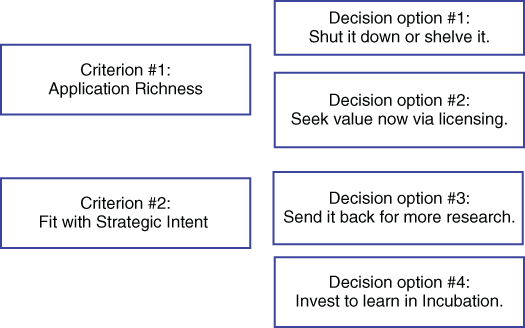

Remember the ABCs: Admit what you don't know. Assumptions count on this mind-set. The outcome of this evaluation process is to decide what to do next. Should we invest in this opportunity to move forward to Incubation and learn more from the market? Does it require additional Discovery work or scoping before this decision can be made? Should we look for revenue streams via licensing, especially for Discoveries that do not fit with our strategy? Or should we simply not pursue it at this time and put it on the shelf or back burner, knowing that there might be a better time or alignment of ideas in the months or years to come. See Figure 6.1 for a summary of decision criteria and decision options.

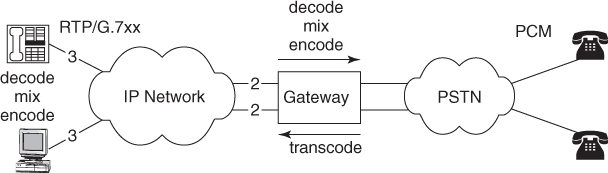

This last point about timing is best illustrated by another story. How many times have you seen seemingly unrelated ideas come together to form a compelling business opportunity? I have seen it happen over and over again. This is why we put certain ideas and opportunities on the shelf, not in the delete file. One of our greatest contributions to a Nortel business division in the late 1990s was a bridging or gateway solution to enable the emerging Internet protocol (IP) network and the public switched telephone network (PSTN) to communicate, as illustrated in Figure 6.2. This business opportunity came to Dylan by combining a fourth idea he was screening with three others he had already screened and rejected. He did not build out this business concept alone, but worked with the originators of the first three ideas and the fourth, who had become key players in the informal opportunity recognizer network. This would have been unlikely to happen without our ideas repository, the opportunity recognition skills we had developed, the richness of our internal networks, and Dylan's organizational memory. What is even more interesting is that discussions are taking place in 2013 to see if now is the time to retire the PSTN networks and transition to networks running IP only. Clearly, the PSTN to IP bridging or gateway concept provided value for a very long time.

Application Generation and the Business Vision

We introduced Discovery as the place where we Plant a business vision of what could be, not what will be, since we do not know yet. So how do we get the game in play, when we most certainly do not have answers to standard product development questions? We do not even know what the product is yet!

This is where the business vision comes in since we are betting on future potential. How do we tell the story in a compelling way to at least have some room to play and experiment with business concept options? The answer is that we require a broad range of application areas to maximize our options since many of these applications will result in dead ends once we test them in the market. With an extensive list of application areas, we can then make an assumption, based on order of magnitude, not detailed market size calculations, that the market is big enough to warrant our attention. We also need to link the opportunity with the company's future ambitions or strategic intent, as Moen did such a superb job in defining. This way we can offer some level of confidence in the potential of the business opportunity, in the absence of a credible business case. It is worth emphasizing that as part of communicating the business vision, applications need to be articulated in terms of the end game of what value they could bring to the market, not necessarily what value would accrue to the company; often it is too early to know.

In generating applications, it requires divergent, not convergent, thinking to generate as many applications as possible. A repository of applications is required. Most often, it takes many application ideas to identify opportunities that could become Incubation projects. So how do companies uncover application ideas? The following are some of the techniques companies have used (and you can, too):

- Interview anyone you believe can be a source of applications ideas. This is how opportunity recognizers, such as Dylan, uncover and shape their opportunities through their specialized networks.

- Interview the originator of the idea.

- Interview others with deep technical or market expertise in the same area of science or business in industries other than the company's.

- Interview others with deep expertise in adjacent areas of science or business involved in your company's industry and in other industries.

- Interview lead users or early adopters of technology.

- Monitor what is going on in the thought leader networks and on the fringes where the disruptions occur. Our Nortel neural network venture, to detect fraud in telecommunications, originated from leading-edge research at a UK university.

- Review governmental requests for proposals or competitions.

- Investigate programs taking place in research institutes and universities.

- Read widely: technology, innovation, business, science, and other publications. Innovation happens at the intersection points.

- Attend professional conferences focused on emerging trends to inspire you. I attended a smart card conference in the early 1980s to develop our Calling Card strategy, long before the commercial application of smart cards.

- Work with companies able to match your Discovery quests with the outside community of experts. Westinghouse and other companies are doing this to tap into the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) companies through the Innovation Development Institute.

For the early evaluation of applications that you generate and positioning of your business vision, there are two major criteria to help you consider the overall business potential:

- Are there many product or process opportunities? Are there whole families of products?

- Will exploration of the application connect the company to new partners? New market domains?

- Are there several differences that the application market values, not just one?

- Could we deliver upon our strategic intent through the pursuit of this business opportunity?

Discovery provides the foundation and Plants the initial business vision of what could be, which is likely to shift over time based on what you learn (see Figure 6.3). This business vision is important to provide you with the credibility and strong footing from which to Pivot in Incubation. Four key insights to carry forward with you from Discovery to Incubation are:

- Skills are required to combine, elaborate, and develop ideas into opportunities.

- The most important critical success factor is the ability to tap into informal internal and external networks.

Figure 6.3 Discovery Insights for Plant

The Discovery Toolkit in Brief

With these Discovery principles and insights in mind, the Discovery Toolkit has been developed to help you transform your ideas into opportunities and learn how to make the case for why more investment is required in Incubation to test business concepts in the market. We want to avoid analysis paralysis in Discovery. The fact is that there will be more questions than answers. Therefore, we need to get the questions right. The answers come by engaging in market experiments during Incubation and doing this as early as possible. This is the only way to uncover the true potential (or lack thereof) of higher-uncertainty innovation opportunities.

Standard Tools

The Discovery Toolkit is available on our website at www.innovation2pivot.com. We hope you take the time to experiment with these tools and maybe even make some progress in turning your idea into an opportunity. The following tools make up the Discovery Toolkit, and each is described in the following subsections:

- Idea Uncertainty Assessment Tool.

- Genesis Pad Opportunity Description.

- Opportunity Screening Criteria.

- Opportunity Potential Questions.

- Uncertainty Identification Checklist for Discovery.

- Opportunity Stakeholder Positioning Steps.

- Plant or Discovery Value Pitch.

Idea Uncertainty Assessment Tool

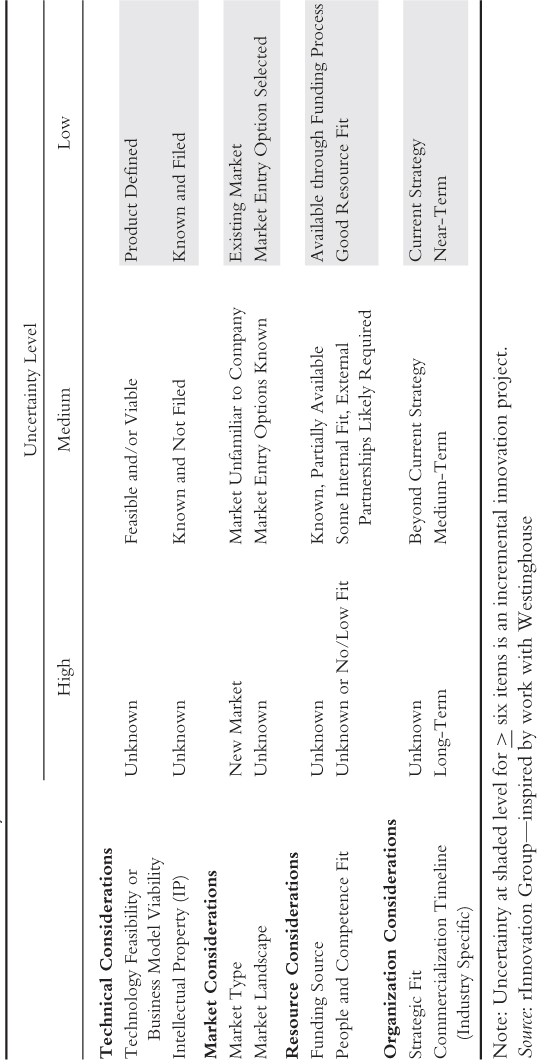

Are you unsure how to determine the level of uncertainty you face with your idea? The Idea Uncertainty Assessment Tool in Table 6.2 has been developed to help you decide. If you are facing medium and high levels of uncertainty, then the D-I-A approach is the right one for your idea and you will benefit by using the Discovery Toolkit. If you are facing low uncertainty, then you are likely dealing with only an incremental improvement, which should be sent to your product development process for consideration. It should also be a lot easier for you to position the value of your idea, since you know a lot more. If you do happen to be struggling with this positioning or with making your case, the Discovery Toolkit might still be able to help. We have been told throughout the years that the principles guiding these tools also help in the incremental innovation space. While this was not our intent, try it on and see if it works for you.

Table 6.2 Idea Uncertainty Assessment Tool

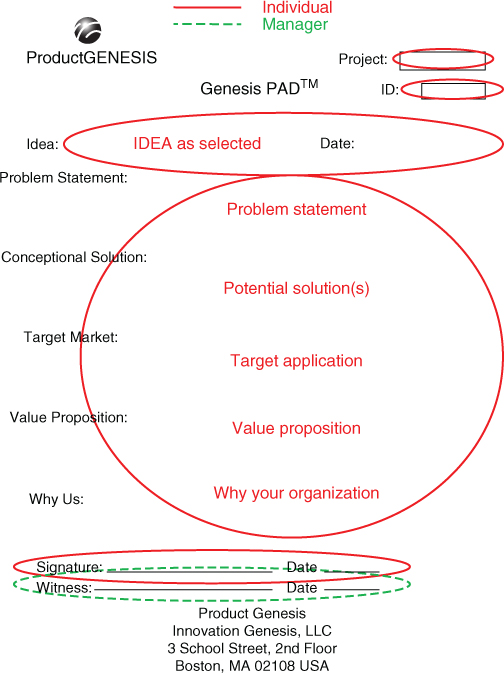

Genesis Pad Opportunity Description

Are you having trouble translating your idea in to an opportunity? The Genesis Pad Opportunity is a tool that enables you to take your raw idea and translate it into a potential opportunity hypothesis. The structure of the Genesis Pad, and the information requested, guides you on how to flesh out your idea in sufficient detail to describe it as an opportunity, without a lot of time and effort on your part!

Questions to help you get there, as covered in Figure 6.4, include:

- Problem statement. What is the problem that needs to be solved?

- Conceptual solution. What are some possible solutions to the problem (or at least solution directions)?

- Target market. Who gets the value from solving this problem—who cares about it?

- Value proposition. What is the value of solving this problem?

- Why us. Why is this our problem to solve? Why is this our opportunity rather than someone else's?

Opportunity Screening Criteria

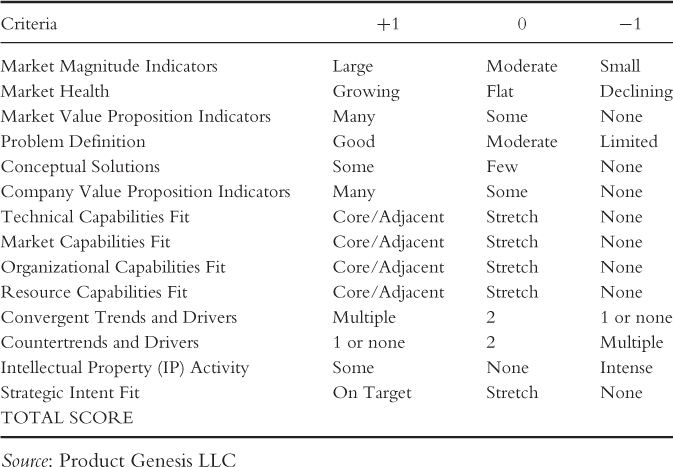

Are you wondering how to conduct an initial screening of your idea to compare its potential as an opportunity with your other ideas or those of colleagues? The Opportunity Screening Criteria are used to quickly evaluate the relative merits of multiple potential opportunities. This tool uses high-level criteria that are relatively easy to apply as a frame of reference without extensive time and effort. The Opportunity Screening Criteria in Table 6.3 include indicators of a given opportunity's potential from a market perspective; its fit with the company's technology, resource, and organization capabilities; and its alignment with the strategic or innovation intent.

Table 6.3 Opportunity Screening Criteria

To score your opportunity, treat all criteria equally. We are not trying to build a computational model! Remember we are in the world of uncertainty and just want to get a sense of whether there is any potential. Score each criterion as either +1, 0, or –1, and then sum up all your scores, adding or subtracting as you go. If you score above +5, then your opportunity has potential, so keep working through the tools. You might also want to include a hard disqualifier for certain criteria, where you must score +1. If you don't score +1, then you set this particular idea or opportunity aside. Grundfos did this to ensure that an opportunity contributed to its innovation intent pillars of Concern, Care, and Create. A positive score was required on at least two of these three pillars to qualify as part of its organizational commitment to sustainability.

Opportunity Potential Questions

Are you having trouble making your case and being heard in a culture that focuses on the short term? The Opportunity Potential Questions in Figure 6.5 are designed to help you think about what you can reasonably address during Discovery based on the uncertainty you face. From our research, getting from idea to business opportunity is the first discontinuity to be overcome to achieve commercial success. You will need to make a number of assumptions to move forward. This will help you to present your opportunity in a compelling way so you can at least make the case for why your opportunity is worthy of consideration based on its richness of applications, a big enough market, and a clear business vision.

I want to mention this vision thing. With hundreds of coaching sessions to reinforce this message, most people struggle with defining a business vision. What we do now is discuss what is possible and what is more likely to occur in the shorter term. We then develop a road map of strategic options, which become more uncertain over time. It is difficult to step out of your comfort zone and challenge the status quo. We are uncomfortable describing any business opportunity without the facts. However, as explained in the story of Dylan and Frank, this is the world of possibilities. We have to paint the picture of what could be based on assumptions, not facts. Do not be afraid to admit what you don't know (remember the ABCs) and step out!

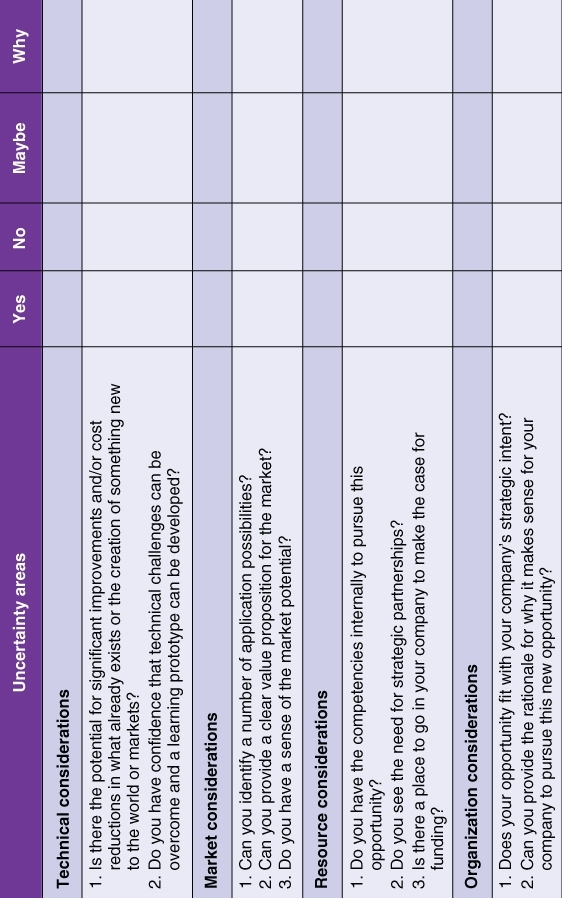

Uncertainty Identification Checklist for Discovery

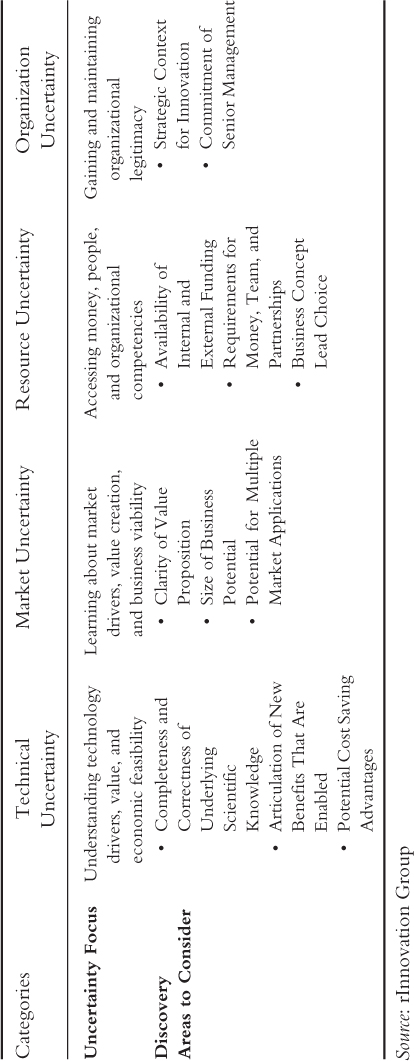

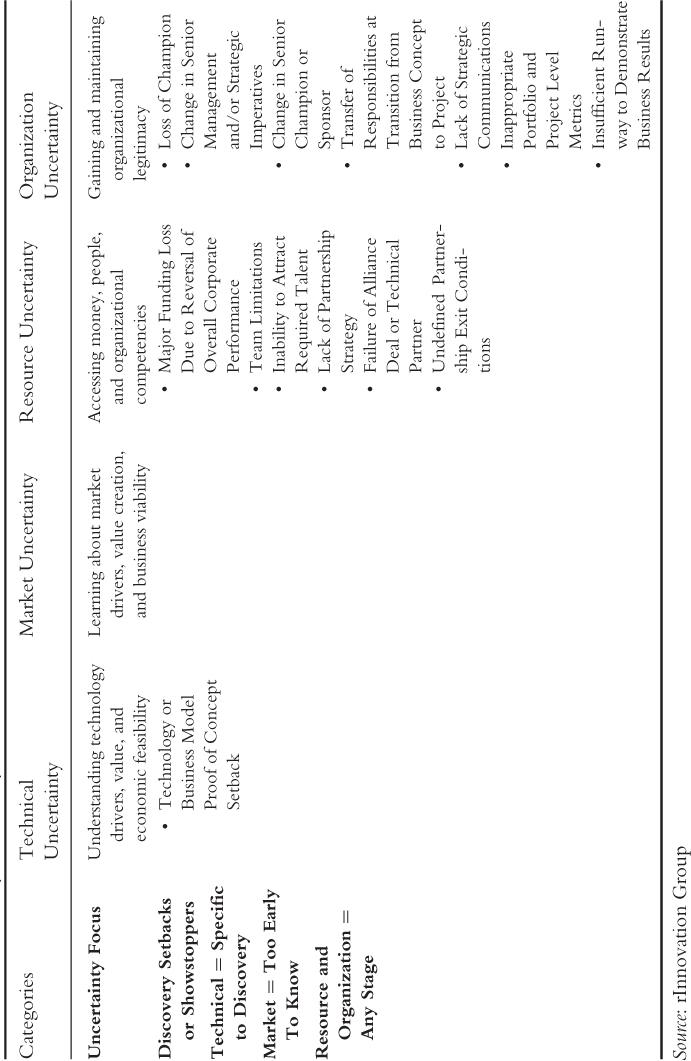

Are you having trouble identifying your uncertainties or even knowing how to think about them, especially in the resource and organization areas? The Uncertainty Identification Checklist for Discovery in Tables 6.4 and 6.5 is a complement to the Opportunity Potential Questions to help you think through technical, market, resource, and organization uncertainties. It has been developed based on the experiences of many projects and has two parts. It identifies areas for you to consider and setbacks or potential showstoppers that could get in the way of your success.

Table 6.4 Discovery Uncertainty Identification Checklist—Areas to Consider

Table 6.5 Discovery Uncertainty Identification Checklist—Setbacks or Potential Showstoppers

Opportunity Stakeholder Positioning Steps

Are you unsure how to position your opportunity to get your stakeholders on board? The Opportunity Stakeholder Positioning Steps in Table 6.6 help you with this positioning. It is your homework to clarify the messages in your value pitch that your stakeholders need to hear. They all have different motivations and expectations, so you need to understand this to put together an effective value pitch, as described in the next subsection.

Table 6.6 Opportunity Stakeholder Positioning Steps

| Strategic Communication Steps | Positioning Questions |

| Objectives | What is required to build organizational alignment and manage stakeholder expectations for your opportunity? |

| Organizational Value | What is the perceived and actual value of your opportunity? |

| Stakeholder Identification | Who needs to be influenced and why? Senior leadership and peers. Supporters and resisters. |

| Stakeholder Motivations and Expectations | What is important for your stakeholders to get their support? |

| Compelling Messages | What are the most important messages to effectively influence your stakeholders? |

| Communication Options | How do you best reach your stakeholders? Face-to-face, social media, other. |

| Positioning Plan | What will you do, by when, and how? |

Source: rInnovation Group

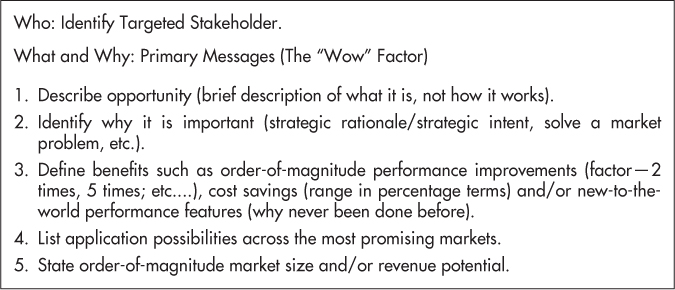

Plant or Discovery Value Pitch

Are you struggling with your value proposition and how to deliver it in a compelling way so it can be heard? The Plant or Discovery Value Pitch (or “reason to believe,” as some companies use in their strategic intent development) is a powerful communication tool and becomes your value proposition intricately linked with your business vision. The goal is to attract interest in further discussions, not provide a detailed explanation of the opportunity's merits. All team members and key stakeholders should be able to deliver an effective value pitch, which evolves and becomes more effective through iterative learning. You should be able to develop an effective value pitch early in the life of your opportunity, even if it is based only on assumptions. If you cannot, you should ask yourself why. Is there an underlying problem with finding the potential value drivers? Or do you perhaps lack the skills to put it together and deliver it effectively?

Our Plant or Discovery Value Pitch guidelines have been adapted from the startup world for the corporate audience. The objective is to address organization and resource uncertainties up front by addressing strategic and organizational alignment issues early. It is amazing how effective it can be when done well, and yet many people struggle with its purpose. Many great ideas go nowhere because the idea originator lacks the skills to make the pitch. Of course, not everyone will be prepared to invest the time to learn this skill. However, if you believe in the potential of your business opportunity, then you should invest that time. If you want to get important stakeholders on board to build organizational support, then you need clear messages. This tool helps you to get there.

It is based on the principle that if one runs into an important stakeholder in a hallway, cafeteria line, airport, or elsewhere (even the elevator, although less likely in Denmark since there are few tall buildings, as I joke with my colleagues there!), you have the amount of time during a brief encounter to convince this person that a meeting would be worth his or her time.

It is now time to build upon the work you have done to translate your idea into an opportunity through Genesis Pad Opportunity, evaluate the potential of your opportunity based on the Opportunity Screening Criteria and Potential Questions, and identify your messages in the Opportunity Stakeholder Positioning Steps to develop your value pitch. Refer to Figure 6.6 to help craft your value pitch and the following tips for its delivery:

- Delivery time should be one minute or less, yet there will often be only 30 seconds before the listener tunes out.

- The pitch needs to start with a point that will attract that person's attention. Therefore, value pitches need to be tailored to the expectations of the listener. This is done through homework by understanding the potential audience, practicing the pitch, and being able to adapt accordingly when encountering a key stakeholder in an impromptu situation.

- It requires developing three main messages that would appeal to a broad interest base. The three most commonly used are linking your opportunity with the company's strategic drivers, describing the opportunity's market attractiveness, and making assumptions about its potential economic value. You should be able to start with any one of these messages and loop back to the other two, depending on the person or group being addressed. This is what we call the media technique, which is what we learn when we answer questions in a potentially intimidating interview situation. One wrong answer could make the company's shares topple!

- The value pitch addresses, as you move through Discovery and Incubation, the following critical questions:6

- What is the market problem that you are looking to solve?

- What would be the economic value of solving that problem?

- Who has the problem?

- Do they have money, and how much would they be willing to pay (Note: Most often, this can only be addressed in Incubation)?

Who: Identify Targeted Stakeholder.

What and Why: Primary Messages (The “Wow” Factor)

Figure 6.6 Value Pitch Checklist for Plant

Source: rInnovation Group

Advanced Tools

We have also designed more advanced tools for the innovation professional, such as the Innovation Ambitions Spider Chart, the Opportunity Scan with Market, Technology, and Intellectual Property Dimensions; the Opportunity Recognition Tool, Opportunity Discovery, the Discovery Questions, the Discovery to Incubation Transition List, and the Business Concept Template. Once you have mastered our standard tools, then you can move to these more advanced tools, available on our website.

Innovation Ambitions Spider Chart: This tool helps you and your organization define the playing field or landscape that you want to explore for new opportunities. The Innovation Ambitions Spider Chart is composed of Opportunity Dimensions (axes) and Opportunity Characteristics (tick marks on the axes). Opportunity Dimensions describe the major attributes of potential opportunities, from a market, technical resource, and organization standpoint. Opportunity Characteristics describe specific capabilities that are needed in each dimension. Capabilities are plotted along each dimension axis, starting at the center with capabilities that are core to your organization today, and moving outward into stretch capabilities and then opportunistic capabilities. The outer bounds of the core and stretch regions are outlined on the chart. Opportunities that use only core capabilities are the easiest to execute on (and may belong in the core business). Opportunities that require some stretch capabilities are the likely target for Discovery activities. Opportunities that require capabilities outside the stretch zone should be approached very cautiously. These are often so foreign to the company that they cannot be evaluated for practical purposes.

Opportunity Scan with Market, Technology, and Intellectual Property dimensions: This set of tools allows for the structured identification of potential opportunities, and provides a framework for conducting these high-uncertainty investigations. These investigations start with defining the playing field or landscape based on a delineation of organizational capabilities, visualized in a spider chart. This is followed by a structured research mining approach to learn how to extract future-oriented information based on meaningful trends and drivers that could create potential opportunities. Convergence screening is then conducted to identify convergent trends with strong potential, divergent trends with weak potential, and fractal trends with unknown potential due to very high uncertainty (this might require use of a scenario-based analysis rather than direct trend and driver analysis).

Opportunity hypotheses are developed from logical combinations of problems to be solved, potential solution approaches, target markets or applications, and market and organizational value propositions that are indicated based on the convergence of trends and drivers. Additional validation research is conducted to fill in gaps in the available information to complete the Opportunity Selection Criteria evaluation. More in-depth opportunity screening is then undertaken to score opportunities based on the Opportunity Screening Criteria in Table 6.3 to decide on which opportunities show the most promise.

Opportunity Recognition Tool: This tool builds upon the Opportunity Potential Questions. It is focused on a more detailed consideration of project initiation requirements. The intent is to stimulate and sustain the flow of ideas generated by internal and external scouting activities into the project initiation pipeline. It lists by order of importance the issues to be considered across technical, market, and strategic areas to make a compelling case for further investment. It is designed to help technical, marketing, and innovation resources work together to make a strong case for pursuing this opportunity.

Opportunity Discovery: This set of tools is designed for both individuals and teams to perform structured exploration of the voice of the market. The approach begins with a carefully crafted research strategy, designed to facilitate the translation of opportunities into market needs, potential solutions, and business concepts. The research strategy is driven by sequential passes of in-market in-depth interviews. The research starts with thought leaders and industry experts to gain an understanding of high-level value drivers in the market, trends creating new needs, and general operating characteristics of the market. From there the research spirals into lead users and lead stakeholders, individuals who represent the extreme-need case within the potential opportunity, and informs the researcher about the strength and depth of the market value drivers, potential early adopter segments, and market entry points. The final spiral of research includes core users and stakeholders, those who may have some needs today but who are much less motivated to action. This research layer helps identify the potential market timing and the total solution requirements for broad adoption within the market.

Discovery Questions: These more in-depth questions help you work more systematically across technical, market, resource, and organization considerations. They are designed to ensure that the right questions are asked during Discovery, with the objective of reducing these four uncertainties to prepare an opportunity for Incubation.

Discovery to Incubation Transition List: This list ensures that all the appropriate Discovery issues have been considered to increase the chances for a successful transition from Discovery to Incubation. It will help with completing the Business Concept Template and building confidence in the business vision, feasibility of the opportunity, and the organizational alignment process.

Business Concept Template: A more formalized Business Concept Template facilitates the decision-making process when faced with high levels of uncertainty. Companies often attempt to design these processes to remove the risk from the equation. This alone will curtail the flow of opportunities and impede the progress of innovation. We promote the principle that uncertainties must be clear up front to reduce them, since the risks are not even identified yet. The Business Concept Template is developed from Discovery learning to provide the rationale for moving an opportunity from Discovery to Incubation.

Words of Caution

The purpose of the tools is to enable your learning. If they are used as a means to control opportunities, innovation will be stifled and application of these learning aids will be perceived as simply another bureaucratic process. You must be mindful of the careful balance between people and process. This is why we focus on the D-I-A mind-set versus process and try to stay away from too much reference to process. Market exploration and experimentation by their very nature require that variation be maximized to gain an understanding of the landscape.

Learning is not a sequential experience, nor is it ad hoc. Rather, it requires situational learning where flexibility, fluidity, and improvisation are the name of the game. These tools and methodologies are to be utilized to enable the process of recording what needs to be or has been learned, identifying where to focus next, and determining how much to invest in terms of money, people, and partnerships. Keep these words of caution in mind as you use the tools throughout the D-I-A model. I have been known to go into coaching situations and reset teams since the process was getting ahead of learning objectives—it's not a good idea to put the cart before the horse!

Plant Your Value Pitch: Making the Transition to Incubation with Your Opportunity Concept

Now it is time to put together your organizational story for why your opportunity has potential and is ready for Incubation. This is your opportunity concept, developed from the elements that make up your value pitch as follows:

- Concise market value proposition.7 This is a statement of what your opportunity could do for or to the market, not necessarily for or to the company at this point, since it is often too early to know.

- Potential lost value. This is a clear statement of what ignoring the opportunity could do for or to the company. Often, the consequences of not pursuing an opportunity are more easily understood than its potential.

- Compelling business vision. Your opportunity is big enough to warrant attention. Some companies even ask, “Is it ‘millionable’ or ‘billionable’?”—interesting terms. It could possibly become a new business opportunity or technology platform for your company. Do not be afraid to step out. Remember, if it is only an incremental improvement, then you should proceed to your product development process. We are in the game of uncertainty reduction first, then managing the risks of product development.

- Market size, growth rate, and application richness. You will most certainly need to make assumptions about market size and growth rate, yet you will also need to look beyond them for a thorough listing of potential applications to ensure robustness of the opportunity. Higher uncertainty leads to higher failure rate. We need to know if there are a number of options to draw from.

- Identification of critical uncertainties. Be clear on your most pressing challenges and potential showstoppers, along with your level of confidence they can be overcome, where low confidence is less than 50 percent, medium is 50 to 75 percent, and high is greater than 75 percent. We want these uncertainties identified up front so we can address them in Incubation.

Are you now ready to Plant your value pitch and move to Incubation?

I hope you are now starting to get a feel for what Discovery is and what it is not. The goal is to help you avoid the ominous valley of death between conceiving of an idea and seeing it realized commercially. Discovery is the first part of your innovation journey to create a common language for and understanding of the innovation life cycle. As we have seen, Discovery can start with any insight, whether it is of a technical nature from scientific work or other. This insight alone is insufficient for you to be heard, and this is where opportunity recognition skills and value articulation come in to help you attract organizational attention. The Discovery Toolkit helps guide you through the uncertainties others have faced in crossing this valley.

In addition to all the principles we have already covered in Discovery, there are two of these principles that you need to bring with you to Incubation—the D-I-A learning mind-set and a razor focus on “learning per dollars spent” (spend the least to learn the most).

Think of “learning per dollars spent” as your Incubation mantra. The phrase came from the vice president of strategy at Air Products, but Dorte Bang Knudsen at Grundfos was the first to call it a mantra. It is now time to move on to Incubation (Pivot). This mantra will become much clearer in Chapters 9 and 10. I am confident you have made a compelling case for transitioning to Incubation, and we are now ready for this next step! Are you?

First, let's see what Remy has to say about opportunity and the entrepreneur in the following chapter and what Gina and Lois have to say about our perspectives on the pursuit of opportunities in Chapter 8.

Notes

1. Material from this chapter is drawn from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) Phase I and II research; Richard Leifer, Christopher M. McDermott, Gina Colarelli O'Connor, Lois S. Peters, Mark Rice, and Robert W. Veryzer, Radical Innovation: How Mature Companies Can Outsmart Upstarts (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000); and teaching, training, and coaching experiences.

2. Gina C. O'Connor, Richard Leifer, Albert S. Paulson, and Lois S. Peters, Grabbing Lightning: Building a Capability for Breakthrough Innovation (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2008), chap. 3.

3. Procter & Gamble website.

4. Mark Rice, Donna Kelley, Lois Peters, and Gina Colarelli O'Connor, “Radical Innovation: Triggering Initiation of Opportunity Recognition and Evaluation,” R&D Management 31, no. 4 (2001); and Gina Colarelli O'Connor and Mark P. Rice, “Opportunity Recognition and Breakthrough Innovation in Large Established Firms,” California Management Review 43, no. 2 (2001): 95–116.

5. Gina Colarelli O'Connor and Mark P. Rice, “New Market Creation for Breakthrough Innovations: Enabling and Constraining Mechanisms,” Journal of Product Innovation Management (JPIM) 30, no. 2 (2013): 209–227.

6. Adapted from “Every Entrepreneur a Salesperson,” MIT Entrepreneurship Development Program (EDP) 2003, Ken Morse, senior lecturer and managing director, MIT Entrepreneurship Center.

7. Gina Colarelli O'Connor, “Market Learning and Radical Innovation,” JPIM 15 (1998): 151–166.