Chapter 9

Incubation—Discipline Together with Chaos1

Do you have time for a few more stories about the corporate entrepreneur before jumping into the Incubation principles? In my days as a corporate entrepreneur, I learned only too well that this world of uncertainty requires thick skin. After my experiences at Nortel, I wrote an article remarking that there is a unique passion and commitment (along with an element of masochism) required to ride the wave of chaos, change, and uncertainty. Change is not easy. Getting someone to believe in the potential of your opportunity is the easy part, or at least it was for our Nortel team.

It is also the view of Alan Schrob, who was director of new business development at NOVA Chemicals, when we worked together. As he described, “Incubation for us was the most critical phase. The learning we did during Discovery was incredibly important in terms of understanding the opportunity, but Incubation is when the risk profile changes dramatically, investments begin, agreements are constructed, and prototypes are tested in the marketplace.”

While we did not call it Incubation in our early Nortel days, this is what we were aiming for. It is where the rubber hits the road, and a long and winding road (borrowed with appreciation from the Beatles) at that, due to all the uncertainty we have to deal with. It is the time when patience wears thin because people are looking for more immediate results.

This goes back to all those resource and organization uncertainties that we were not good at describing back then…if I had only known then what I know now. I wanted to get these points raised now, as we step into Incubation. This chapter and the next provide insights and tools for living with this inevitable chaos.

I have asked Alan and other colleagues to share their Incubation insights and stories to make this as real for you as possible. I selected three companies committed to getting Incubation right that I know well—NOVA Chemicals, Moen, and Grundfos. Let's start with Grundfos, one of the world's leading pump manufacturers. Some of you will be “out there,” as Lars Spicker Olesen, chief incubation officer at Grundfos, will explain next, and some of you will not. We call it the missing link in companies for a reason. There are still too few who do it well, and this becomes a large contributor to the high failure rate in product development. How many meetings have you been in where you speak of learning loops and uncertainty reduction? Incubation is about getting out in the market to learn. It requires the ability to learn quickly, redirect, and improvise. It is about reducing uncertainties early to increase the success rate of product development.

Lars shares three of his many Incubation experiences to best illustrate these points.

Engage the experts—thinking behind a desk has a limit. In one of our projects, we were targeting an application relevant for dairy farming. To assist in getting to the very first technical solution, we contacted a consultant. He brought with him a colleague who had established an entire business around the exact same concept (based on another technology, though), and from her we learned all about market drivers and barriers, technical benchmarks, relevant progressive first customer partners, and how to tackle legislation for our new approach. Needless to say, luck also came into play, but it is difficult to get lucky if you do not play or, in other words, are not out there.

Decide—often. I made a motto after having run several projects of a highly uncertain nature. One should not underestimate the effect of actually doing something, instead of just talking about it. Sometimes (quite often in these projects, actually), we simply cannot think it up. But by trying just something, we get a little bit wiser and understand more about what it is we don't understand. Short learning loops and building on learning are the easiest things to say, and the hardest things to actually do. So decide also about things that are not nice, like closing a project; but still, decide. The Learning Plan (described later in the chapter) has been a great tool for helping us to do this.

Go with the flow of learning. To keep an open mind and keeping options for a business in play is difficult, once one gets the first few successes. When something is not working, it is easy to try something else. When something is working, it is hard to not hammer only on that thing and perhaps not see the full potential. In developing a concept that had interfaces toward two existing systems, owned by different entities, we learned that our exact same technical solution could be used in another application, where marketwise we only had to convince one entity. And yet, we still went after our first, more complex market positioning concept because we were already on this path with a functional, technical prototype. I am still not sure whether that was the right idea.

Lars must be wondering if this could lead to yet another failed product development or, at the very least, an opportunity that is incrementalized in terms of its overall business potential, because the opportunity to revisit the scope and redirect to, perhaps, a better learning application area has not been fully considered.

Let's see how these experiences carry over to the Incubation principles.

Incubation Principles2

While Discovery is about the conceptualization of business opportunities, Incubation is a competency based on experimentation to uncover latent or hidden needs and next-generation concepts. This requires the ability to experiment with multiple technology and business concepts or models simultaneously. The objective is to arrive at a demonstrated model of a new business opportunity and bring game-changing value to the market and, consequently, to the company. Integrating the technology and market learning together differentiates this approach from the serial product development process, where, most often, the product is developed and then brought to the market.

There is an acceptance of failure as integral to the learning process—failure by design, as it is often called. Despite these failures, we expect experiments to continue. Incubation reinforces the need for the creation and pursuit of options, with movement in multiple directions simultaneously. There is a focus on learning and redirecting. Critical to this is enriching and extending internal and external networks. This is required to enlarge the scope of the company's knowledge base and commercial opportunity space. This must be done in the market to really be “out there,” as described by Lars.

In Incubation, many application possibilities are tested, yet few enter Acceleration. Incubation requires working through tests in parallel through iterative learning, not the serial product development or phase gate approach many companies have in place today. The Incubation competency encompasses strategic coaching, opportunity and relationship brokering, portfolio thinning and enriching, and nurturing skills.

Coaching is required to help people make strategic linkages and to understand the uncertainty-reduction process and how to deal with an ambiguous environment. Brokering provides connections to sources of knowledge, resources, and politically important players to build project support and to access the right internal and external networks. Thinning and enriching of the portfolio are undertaken frequently, due to the high churn rates associated with iterative or spiral learning. Options are tested, then redirected or eliminated, as this learning occurs. This is difficult to manage, because the need for failure is not well accepted. We see evidence for this by the corporate pressure for high success rates. There is also a tendency toward incrementalization by force-fitting a concept to what is known, to lower the risk and, therefore, the potential for failure. When faced with all this uncertainty, teams need to be nurtured through compassionate leadership and by establishing the line of sight, with the company vision to provide a sense of direction and a reason to believe.

Let's revisit a few stories to illustrate these points, starting with coaching based on Alan's experiences. “We leveraged coaching sessions with project teams to work through uncertainties and ensure the correct learning took place. These sessions allowed the project teams to step back from the detail and project activities to review their progress in uncovering uncertainty, in the technology and the proposed market, as well as resource and organizational uncertainty. We designed these sessions to not be critical but more to allow the teams to think more strategically about the opportunities they were working on.”

And how do companies deal with failure and tap into expertise?

Steve Pierson, chief business innovator at Grundfos, shares this story with us.

Learning loops were invaluable for reducing uncertainty in an efficient manner. Learning loops can yield success, failure, and learning. The first learning loop for one of our projects was a complete failure, but we didn't want to admit it. We should have made the call to kill the project as soon as the project began to show it would not be a good learning platform, but this would have created embarrassment and an admission that we didn't take into account the unknowns in our planning. While we did identify them, we dismissed them and went on with business as usual. As our experience grew in the use of the D-I-A approach, we actually focused on addressing these unknowns and embraced failure as much as success, because we viewed it as learning.

From our failures, we decided to experiment in our second learning loop and use an external partner who specialized in building controls in the wastewater and water treatment industry. This partner built what we needed in a fraction of the time and cost that it took us in our first learning loop, and it performed as specified. By sensoring the system to measure key performance indicators we determined that the project was a complete success and saved between 30 and 40 percent in energy costs for the commercial building owner. Furthermore, we had an unintended consequence of our experimentation and found a faulty component with one heat pump, which would not have been discovered without sensoring the energy usage of each heat pump. Now the facilities manager calls me to ask how his system is performing. He has put trust in me that I have his back and will let him know if any issues arise. We have also found an internal ambassador who values what we do.

Hmmm…Have we also uncovered another opportunity, a service business model for monitoring system health?

The story Lars told us also reinforces that you cannot always think it up; you need to be “out there” experimenting. There could even be unexpected positive outcomes. In Incubation, we also legitimize failure as a source of learning and that success can be just as much about uncovering what will not work as what will.

Incubation Objectives

Based on the principles, let's spend a little more time on the “learning per dollars spent” mantra. Remember Dorte Bang Knudsen calling it a mantra in Chapter 6. This really sets the stage for our Incubation objectives. Business concept or project costs should increase through the early, middle, and late stages of Incubation commensurate with learning. This is an excellent test of whether we are truly focused on reducing uncertainties. The focus is to maximize learning and minimize spending, and to test a number of market-entry options to arrive at a market-entry strategy. As uncertainties decrease, we can then feel more comfortable spending more, because we know more. This mantra is also tied to how we manage the number of learning loops and the length of each one, which we cover in the next section. I simply know by the budget assumptions if someone has a D-I-A or product development mind-set, and in coaching sessions I have forced teams to reevaluate what they really need to spend to learn! Developing a learning prototype requires significantly less investment than building a product prototype for development. When we get to Soren Bro's story in the next section about the German research institute, which mind-set do you think it had?

One time, I almost jumped out of my chair when one young, recently hired entrepreneur, lacking corporate experience, recommended building 10 prototypes in early Incubation at over $100,000 each. In the software world, it is easier to test many options since the costs are lower, yet even these tests need to be carefully managed. If too many variables are being tested simultaneously, then how do we really know what the tests are telling us?

With this philosophy of maximizing learning and minimizing spending, we aim for the Incubation objectives to be about uncovering and nurturing a portfolio of opportunities (or options) of a highly uncertain outcome yet with immense possibility for the market and the company. With the higher failure rate, we need more options to test, yet we have to be creative in the ways we do it, to keep the costs down. This portfolio or options approach also provides the foundation for the development of a serial corporate entrepreneur. When one fails, it is time to move to the next opportunity, building on the skills already developed and leveraging networks to bring in the new expertise required. Since we are still facing too much uncertainty, we also want to develop proposals (not plans) for new business areas based on the outcomes of experiments in the market, with the technology, production processes, value chain, and potential customers. We seek to clarify new strategic growth opportunities for the company and to gain clarity of the value proposition for the market, as well as for other stakeholders. We also look to establish market or customer pull to measure market interest, validated through early trial revenue with customer partners or cost-sharing arrangements with development partners. If others are willing to invest early, this helps to build the case for why we should.

Incubation Activities and Processes

In terms of Incubation activities, our goal is to experiment on many dimensions, including market, technology, and strategic impact. We begin by investigating promising Discovery opportunities where technical feasibility is proven, or we have confidence that it can be, and applications seem robust. Often, the market needs to be educated about the technology or business model. How the technology or business model evolves comes from what is learned in the market. We are looking to interact with the market through application trials in two or three domains to test our options. We work with partners and potential customers to test whether the perceived value founded on assumptions aligns with the team's expectations through the probe and learn approach, which will be described in Chapter 10.

Additional activities include stimulating new market creation and value chain development via partners. This is required because it takes time and money to create a new market, so it is better to share the risks. It is important to emphasize that as business concepts and formulations continue to evolve during Incubation, iterative technical development is required based on what is learned in the market. Remember Lars wondering whether they should have gone after a potentially easier learning application or stayed the course as they did. We do not lock in technical specifications until the end of Incubation. Throughout Incubation, we focus on developing learning simulations or prototypes to test concepts, not develop products.

In mid to late Incubation, once uncertainties have been significantly reduced, we can then conduct credible business case analyses based on the outcomes of market and technical experimentation, with the objective of clarifying the economics of the potential business model. There could also be some initial yet very small revenue generated through trials, along with more substantial partner investment. It is time to establish revenue targets and start the calculations for how this business opportunity could be profitable. While strategic fit and market interest remain the main discussion points, it is now time to start focusing on more traditional financial measures.

Before that, we focus on keeping the game in play by clearly outlining what this opportunity could be. This is why the business vision, as described in Chapter 6, is so critical. By design, higher-uncertainty investments are more strategic. We need to tell a compelling story of what is possible until we have sufficient learning to convert assumptions into knowledge. Finally, as the last of our Incubation activities, we must not lose sight of our near-term and longer-term options in terms of applications, markets, and products to deliver upon our business vision.

As you might expect, the processes to support these activities are nontraditional. They have little resemblance to phase gate processes and involve:

- Learning Plans, which are described in the next section.

- Early market participation with lead users, partners, and innovative customers.

- Market probes that become market launches by creating a potential path to market, and where the company can begin to commercialize early market opportunities. Market probes help to:

- Identify potential new applications to enhance the business vision.

- Build internal credibility due to external interest.

- Learn about cost structures and partnership options.

- Creating a pipeline of opportunities, accepting that failure is part of the design. When one shuts down, there is a better or more promising one to work on. This pipeline helps:

- Provide psychological safety to teams working on projects that are not working out—serial corporate entrepreneurs mentioned earlier.

- Make stop or put on shelf decisions much easier and more efficient since there is more to draw upon. The decision to stop a project should come from the project leader and team since they are in the best position to know.

Let's be clear. Shutting down projects is not easy. The corporate culture is to keep projects alive, even if they have to go underground. I have seen millions of dollars or euros wasted on development projects that seem to have a life of their own. My observation is that once a project is being managed through the product development process, there is incredible pressure to pass each gate and a reticence to ask the difficult questions. Again, it's this fear of failure thing.

Companies also set inappropriate metrics for measuring success. Soren Bro, an Incubation manager at Grundfos, shares the story of his project shutdown experience.

My boss asked me to participate in a meeting with a prominent German research institute. The project was about developing our own microwave UV system together with this institute—a high-uncertainty project on all four MOTR (market, organization, technical, and resource) levels. I was asked to challenge the process with my D-I-A mind-set, and I had a lot of critical questions! A few months after the first meeting, I was put in the project management role. The project was facing fundamental technical uncertainties at that point, and essential benchmarks had not been done.

The institute suggested addressing the performance uncertainty by designing and building a $200,000 test rig and doing the benchmark in the lab. The D-I-A mind-set and tools pushed us to look for an alternative way to test the assumption about whether we would be able to compete with existing players. We knew we did not need to spend $200,000 to figure this out, especially since we were early on in the project. We found an expert in Russia who knew the fundamental limits of the core technology we were utilizing, and in a single phone call and a little e-mailing, this person provided us with the evidence to make the decision to close the project. A great and very fast learning, for little cost!

In the middle of the project, Grundfos introduced personal incentives for all its employees. My personal incentive was decided by my boss and sounded like this: “Finish the scheduled test rig according to time plan.” When the time came to discuss if I had fulfilled this target incentive, I was first told, “You did not make the test rig, which means no incentives.” Of course, I argued that I had actually saved Grundfos a lot of time and money by making the decision to close the project. After further discussion, my boss corrected the result to “full incentives.”

This story I use now to exemplify what the mind-set can do for our organization and that traditional metrics are not suited for this uncertain world of business. The closedown of this project led to investigation into other UV opportunities and finally our Enaqua competency-based acquisition.

So shutdown was not easy for Soren, yet it did lead to an important strategic investment. Fortunately, with his powers of persuasion, which I have seen in our coaching sessions, he did get the incentives he deserved. More often than not, however, this is not the case. This is either because people are not quite so skilled in making their case or because companies simply refuse to accept that traditional metrics are inappropriate when dealing with high-uncertainty projects.

Therefore, the objectives for moving from Incubation to Acceleration are to:

- Ensure that the “learning per dollars spent” mantra has been successful in reducing uncertainty.

- Validate market interest through partner investment, emergence of new applications, invited lectures, press inquiries, technical leadership, and so forth.

- Establish revenue targets and secure early revenue, if possible.

- Provide market evidence that the business opportunity can be profitable.

- Find and develop people with the competencies for growing these business opportunities.

- Revisit strategic fit.

See Table 9.1 for the Incubation Focus Areas from Table 3.3, Innovation Business Opportunity Evolution, in Chapter 3.

Table 9.1 Incubation Focus Areas

| Pivot | Incubation Experimentation Output = Concept Proposal |

| Technical Uncertainty Understanding technology drivers, value, and economic feasibility |

Technology Prototypes, Simulation, IP Strategy and Plan Execution, Product or Solution Specifications |

| Market Uncertainty Learning about market drivers, value creation, and business viability |

Early Adopter Experience, Market Learning, Business Model and Market Entry Strategy |

| Resource Uncertainty Accessing money, people, and capabilities internally and externally |

Innovation Talent and Partnership Development |

| Organization Uncertainty Gaining and maintaining organizational legitimacy |

Structure and Process to Support D-I-A Mindset and Effectively Transition Concepts or Projects |

Source: rInnovation Group

Incubation and Living with Chaos: The Learning Plan3

As covered in the previous section, Incubation is about maintaining alignment with and influencing the strategic intent via the business vision. It also requires ensuring that the right type and level of resource commitment is in place and that the pacing of projects is driven by learning and redirection. Projects should be assessed based on Incubation (not traditional) evaluation criteria and metrics. Internal and external networks are essential to access new sources of knowledge and capabilities, and we cannot lose sight of the importance of uncertainty reduction in market and technical areas as well as resource and organization ones. This is certainly a tall order. How do we manage all of this chaos and uncertainty? This is where the Learning Plan comes in.

First you must accept the premise that chaos exists and we can bring some order or discipline to it. At a presentation I made in London many years ago, I had a discussion about the difference between complicated and complex. I was basically told that we were making innovation complicated, whereas it was not complex. This conversation has stayed with me throughout the years. In the dictionary, the two words are considered synonyms, yet I think of them slightly differently. I agree we do make things complicated. On the other hand, complexity just is. I have tested this over the years. What we are dealing with is definitely complex, when considering four dimensions of uncertainty, having more questions than answers, shifting capacities for innovation, and so forth.

The Learning Plan methodology provides a disciplined approach for managing this very chaotic world by acknowledging its complexity and seeking a way to make it as simple as possible. This methodology is specifically designed for the Incubation environment. We are experimenting with options to uncover the best path for market entry. This is unlike the commercialization focus of product development, which is specific to a target market. This testing of options runs counter to most corporate cultures, yet is essential prior to making the large investments required to commercialize a business opportunity. This is likely why we see such high failure rates in product development and mostly incremental innovation investments.

Short, Quick, Inexpensive Learning Loops

Let's get back to Louise Quigley, director of strategic innovation, and Mike Pickett, vice president of global strategic development, at Moen, from Chapter 3. Louise, Mike, and I spoke of their experiences with the D-I-A systematic approach to learning. Mike has seen a big difference in learning speed.

There is a perception that Learning Plans are slow, but in my experience they can be incredibly fast. In the early stages of development, Learning Plan methodologies can improve the speed of execution by a factor of 10 over typical Stage-Gate processes. The Learning Plans keeps us focused on what we need to know next. We can systematically and iteratively test and reshape our market hypotheses until we arrive at the right solution. In my 25 years of product development experience, this is the most effective tool I have found for working on highly uncertain innovative projects.

Moen has also added an interesting twist to keep up its speed of learning. Louise facilitates regular Learning Plan sessions and explains:

In our Learning Plan sessions, we start with an initial plan and focus on what is most critical to learn next. We go out, conduct learning loop exercises against critical unknowns, review the outcomes, and use the learnings to adjust our hypotheses. Then we go through the process again. You could say we have big learning loops when there is a significant change and small learning outcome loops when there is not. This iterative approach enables us to learn quickly and helps us arrive at the most compelling innovation opportunities.

We are finding that companies are adapting the Learning Plan methodology for their unique circumstances, while respecting the principles of the methodology. With Moen's consumer product focus, it makes sense to consider which steps are essential to maintaining and accelerating learning speed in a fast-paced market. This might be about regularly reviewing learning outcomes but not designing a new Learning Plan until there is a change in course brought on by learning. However, before deciding which approach might work for you, I would highly recommend you first read what the methodology is all about and consider the benefits of training and coaching addressed in Chapter 10. Moen has been on this journey for some time and has been through a number of these sessions to get to where it is today.

The Learning Plan Methodology

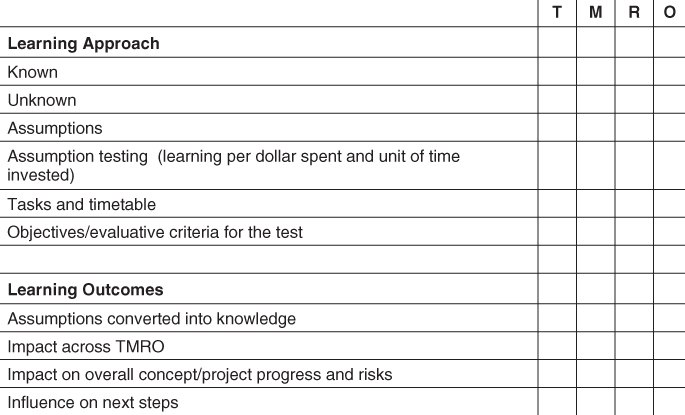

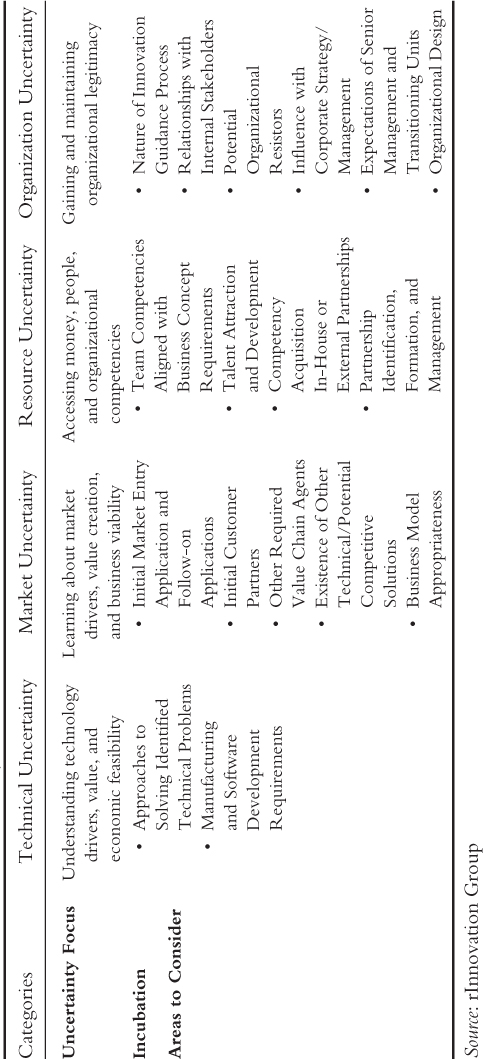

The Learning Plan in Figure 9.1 has been designed as the project management mechanism for higher-uncertainty innovation projects. The objectives are to help with the articulation of project value, serve as a communication vehicle, establish a common language for innovation, and make the learning process more efficient by having a record of the past and a clearly defined path forward. The Learning Plan is to be used for learning at the project level. It is a tool to work through uncertainties. The Incubation Uncertainty Identification Checklist in Table 9.2 is a complement to the Learning Plan to help teams think through technical, market, resource, and organization uncertainties. It was developed based on the experiences of many projects and serves to identify areas to consider and setbacks or potential showstoppers.

Table 9.2 Incubation Uncertainty Identification Checklist—Areas to Consider

The Learning Plan is designed in two parts. The first is the learning approach, and the second is the learning outcomes. The learning loop is the combination of these two parts. The design also ensures that one considers all four uncertainties—technical, market, resource, and organization. Uncertainties will be further elaborated upon in the next section.

In the learning approach, we focus on identifying what we know, what we do not know, and our assumptions. We confirm what we know by asking if we have evidence to support it. If we do not have this evidence, we are likely making an assumption, which becomes an unknown. Based on what we do not know and our assumptions, we then decide what is most critical to address next. We convert our assumptions into hypotheses to provide insights into what tests might be conducted. The nature of these tests can also help define what is most critical. We confirm what is most critical by asking ourselves whether, if we do not address it, it will it get in the way of learning progress and success or have the potential to become a showstopper. We also factor in the amount of learning that can come from these tests and the time needed to get that information.

These become our tests. We set them up based on “learning per dollars spent”—how can we learn the most and spend the least? The goal is the most quality learning for the least amount of time. We also define the tasks and timetable. The timetable is defined by what we need to learn, not a calendar event. How long will it take us to learn this? Therefore, learning tests can take one week or a number of months. Some showstopper tests do take time, or you might have a number of yellow or red flags but no obvious showstoppers in the beginning. This gets back to the focus on what is most critical for us to learn next. We need to develop objectives and evaluative criteria for these tests so we know how to evaluate the learning outcomes to determine if we have been successful. In the learning outcomes part, we evaluate assumptions that have been converted to knowledge and review their impact across the four categories of uncertainty. We also evaluate the outcomes of our tests to see how they are different from what we expected. Learning in one area will have an impact on another, due to their interdependencies. We also need to step back and look at what this learning is telling us about overall project progress and risks. This is where we ask ourselves if we should stay the course or redirect, which will then have an influence on next steps (or even stop the project). These next steps then become the starting point for the next learning loop. With this approach, project reviews are driven more by learning loop completion than by calendar events, as mentioned previously.

This methodology was designed with the steps of a scientific research method in mind: Loop 1—Assumptions or background, hypotheses, data gathering, analysis, results, and their impact on future hypotheses to be tested in Learning Loop 2; Loop 2—Assumptions or background, hypotheses, data gathering, analysis, results, and their impact on future hypotheses to be tested in Learning Loop 3; and so forth. The basis is that we are systematically testing cause and effect around not only technical considerations, but also market, resource, and organization ones, which means we are testing perceptions to see if they have any basis in fact.

Let's get back to another insight, courtesy of Jesper Ravn Lorenzen, Incubation manager at Grundfos, which confirms this.

Many people consider innovation and NBC (new business creation) as quite fluffy, “the fluffy front end.” My reflection is that the D-I-A mind-set and methodology are actually a replication of the scientific method, albeit on another abstraction level.

I acknowledge that NBC requires special professional and personal traits to handle the uncertainty, but my observation of what makes me an efficient and competent innovation manager is actually something else. I am not very creative in a conventional way; I neither draw nor play an instrument, but I am good at creative problem solving to develop and set up cheaper, quicker experiments than most others can. And this gives me an edge when reducing project uncertainties.

So it seems the Learning Plan is proving to be an effective tool to bring a disciplined approach to uncertainty reduction and make the innovation world a little less chaotic place.

Dimensions of Uncertainty

With all this discussion about uncertainty—even starting in Chapter 2 I said innovation is all about uncertainty—perhaps we should spend a little more time on this topic. I have already introduced the four categories of uncertainty—technical, market, resource, and organization—and we know, through the RPI research and our innumerable experiences with companies, that these resource and organization uncertainties are highly problematic. There are two other dimensions of uncertainty that we also need to address: latency, or what is hidden, and criticality.

Once again, for the categories of uncertainty, the technical component is about understanding technology drivers, value, and economic feasibility. The market component covers learning about market drivers, value creation, and business viability. The resource component covers accessing money, people, and organizational capabilities (internal and external). The organization component is about gaining and maintaining organizational legitimacy.

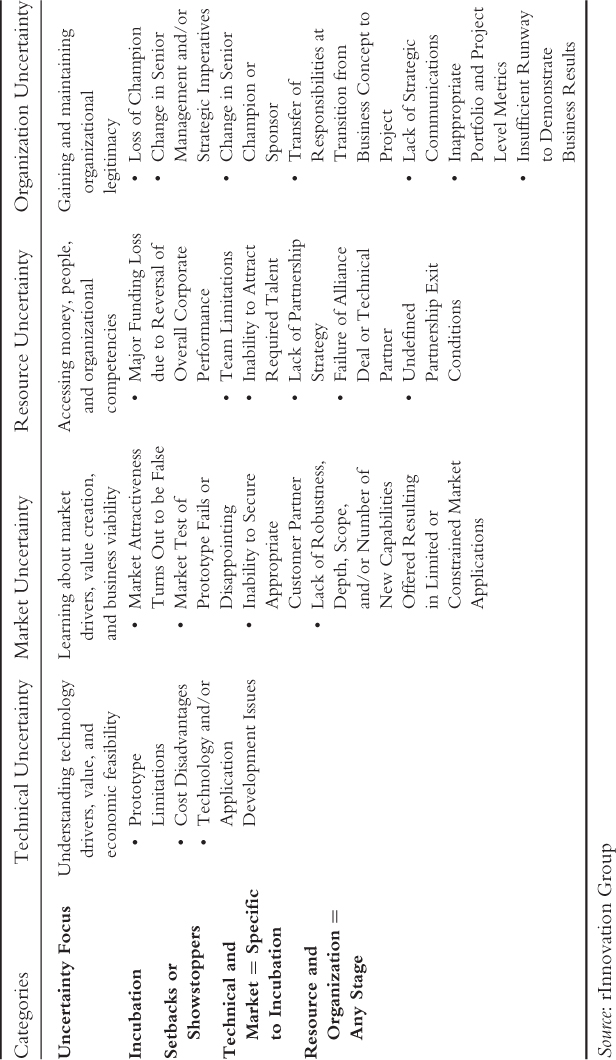

While we have spoken about the importance of identifying potential showstoppers and introduced the Incubation Uncertainty Identification Checklist to help with this, we have not covered how to surface them. This is where the second and third dimensions of uncertainty, latency, and criticality come in.4 This is going to get somewhat technical, and many people still struggle with making these distinctions. See Figure 9.2 for a visual representation of this.

Latency is about uncertainties we can anticipate and those we cannot. Common latent assumptions are: “Our sales force can sell this” (despite this being a solution versus component sale) or “We can find the engineering resources for our project” (despite a limited number of people and skills in the resource pool). Criticality is about understanding what is routine and what are showstoppers. What is routine, whether it be anticipated or unanticipated, will not get in the way of success, but the showstoppers will. A common criticality assumption is: “This fits with our strategy.” This is despite there being no clearly defined strategic intent, and we know lack of fit is definitely a potential showstopper. Therefore, converting the unanticipated showstoppers to ones that can be anticipated and addressing all anticipated showstoppers during a learning loop are priorities. Surfacing the unanticipated showstoppers is facilitated by the Incubation Uncertainty Identification Checklist in Table 9.3, which is a collection of showstoppers captured from the experiences of actual projects. While certainly far from comprehensive, it helps direct your thinking in what could get in the way of your success. Based on experiences over the past 10 years and a company's need to prioritize and focus, there will typically be no more than two to four potential showstoppers or most critical issues to address per learning loop.

Table 9.3 Incubation Uncertainty Identification Checklist—Setbacks or Potential Showstoppers

Before moving on to the next section, where we look at the learning loop development process, Arun Ramasamy, chief innovator at Grundfos, shares his story of the value of focusing on critical uncertainties.

When I took over the responsibility of incubating our water heater opportunity, as is to be expected, uncertainty was fairly high in all four categories—technical, market, resource, and organization. Despite having an engineering background, I had never built or designed a heat pump, let alone led a very capable multidisciplinary team to build a radically innovative heat recovery system. The task was complex in every imaginable respect. The “simple” task of figuring out where one should start in the project would have been overwhelming but for the thinking behind the Learning Plan, a favorite part of the entire D-I-A framework. One of the key insights I drew from this experience was that being focused on critical uncertainties actually led to more clarity on the project. Let me illustrate this with an example.

We were preparing to design and build our prototype system when my boss and I had a difference of opinion. He felt that my claim of designing and building the prototype in 30 days was simply not possible. It should be noted that I'm a product of the software industry and a complete outsider when it comes to heat pumps. Perhaps I was being naive in my estimates. “Arun, you'd need at least four to six weeks to pull together the engineering drawings alone.” To his credit, he let me proceed anyway with my “uninformed approach.” After all, this was supposed to be the first learning loop of the Incubation phase.

What gave me confidence was that similar systems had been built by others and that the objective was to prove that the technology would work, not design a manufacturing-ready system. The engineering drawings, in my mind, were not relevant until much later in the Incubation phase. The prescription to focus on critical uncertainties provided additional impetus to move forward. To make a long story short, we ended up building our prototype in 30 days—and, yes, without one engineering drawing. By focusing on the critical uncertainty of developing a learning prototype to make it real and to demonstrate feasibility, this led us to more clarity than an engineering drawing would have provided.

Now let me jump in here and make a very important point. This discussion happens all the time, especially when people come from product development and operational backgrounds. Coming up with the engineering drawings would have been appropriate for the product development process. How would we get quality products out the door otherwise? Yet, that was not Arun's objective in the early days of Incubation. He was merely taking the next step beyond the proof of concept, knowing there were similar systems out in the market and focusing on what was most critical to learn next.

So everyone has been speaking about these wonderful learning loops. Let's get to it.

Learning Loop Development Process

There are three steps involved in the learning loop development process, and they can seem academic. I encourage you to experiment with this process. Practice makes perfect, and it takes time to perfect the process. It is intuitive for some and not for others. We are going to cover the basics. What is most important to focus on is being systematic. In preparation for a learning loop initiation session, the starting point is your opportunity concept or Plant Value Pitch from Chapter 6.

The first step is to initiate your learning loop.5 The second step is to evaluate your learning outcomes. The third step is to understand the general guidelines to gauge the effectiveness of your learning loop development.

Initiating a Learning Loop

Let's start with your opportunity concept. For each of the four uncertainties, create a page (or use a flip chart) and divide the page into knowns on the top and unknowns at midpage. If you want to get creative, you might want to color code the uncertainties. I like to use black for technical, green for market, and bold colors such as purple and red for resource and organization so they stand out. We cannot forget that they are the ones that get in the way of success.

For each of these four categories of uncertainties, list each of your knowns and provide the source for this evidence of fact to ensure it is not an assumption. Now list your unknowns and your assumptions. Remember to work on what is not immediately obvious or latent using the Incubation Uncertainty Identification Checklist. You will need to go back and forth across the technical, market, resource, and organization areas since one thought will trigger a dependency with another.

Once you feel you have a good sense of what you know and don't know, then identify what is most critical to address next. Remember the test is: Will this get in the way of my success? Set up your tests for these most critical areas across the four categories with objectives and evaluative criteria for the tests. Then develop a plan for what resources are required, how much it will cost, and how long is required to learn what you need to know.

From this exercise, the objective is to identify your critical uncertainties and assumptions and the required tests for addressing them, including what it will take. Remember to use the Learning Plan Design template in Figure 9.1 as a guide. It might also be a good approach for recording your learning.

Evaluating Learning Outcomes

Once you have completed your tests, it is time to update your learning. As part of this, you want to look for any insights on the need to redirect or stay the course. You also want to see if any new uncertainties have emerged, as they invariably do. Remember to look across all the categories of uncertainties for the interdependencies. Now you are ready to complete your learning loop and set up the next one based on what are your next most critical uncertainties, associated tests, and resource requirements (people and money). The cardinal rule is that this process is learning dependent, not calendar dependent. You drive the direction of your learning. There are no predetermined gates. Set your time line always with this in mind. Your goal is not to go through set gates but rather to begin to determine what they might look like.

General Guidelines

Finally, let's consider a few guidelines to help you gauge the progress you are making. It typically takes two to three learning loops to see evidence of gaining traction or market interest and decide whether to continue with a project or application area. If you have multiple applications to test, you need to conduct a learning loop for each application that appears interesting. Combining two or more applications becomes difficult to manage since often different tests are required. Applications can still be tested in parallel, but I recommend you record them separately on the Learning Plan Design template should you choose to use this format. I say “should you choose” because you might even come up with a template of your own. We have experimented over the years on how best to record this learning. It is a very dynamic process that is difficult to capture in a static tool. We have developed Excel spreadsheets and Word documents. Grundfos is using a mind-mapping tool. We are now taking the next leap to an online tool that you will be able to play around with in its standard form or even choose to upgrade to its more advanced version. I will expand upon the Incubation Toolkit in Chapter 10. In the meantime, feel free to experiment!

The final guideline is that your project requires multiple learning loops to be ready for Acceleration. In our experience, there are no fewer than three and no more than seven. These are averages only. The number of loops required will vary by your industry, where software will require fewer loops than renewable energy, for example. It will also depend on your level of project uncertainty. Breakthrough opportunities will require more loops than evolutionary ones. Consider this a rule of thumb only. The final outcome of the learning loop process is the preparation of your concept proposal to move to Acceleration.

As you can see, Incubation is much more involved than Discovery. Let's move on to Chapter 10 so we can elaborate on the road map for getting to your concept proposal. As we tackle the management challenges of how to engage in market learning and think about business models, let's keep in mind this mantra of “learning per dollars spent.”

Notes

1. Material for this chapter is drawn from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) Phase I and II research; Richard Leifer, Christopher M. McDermott, Gina Colarelli O'Connor, Lois S. Peters, Mark Rice, and Robert W. Veryzer, Radical Innovation: How Mature Companies Can Outsmart Upstarts (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000); and teaching, training, and coaching experiences.

2. Gina C. O'Connor, Richard Leifer, Albert S. Paulson, and Lois S. Peters, Grabbing Lightning: Building a Capability for Breakthrough Innovation (San Franciso: Jossey-Bass, 2008), chap. 4.

3. Mark P. Rice, Gina Colarelli O'Connor, and Ronald Pierantozzi, “Implementing a Learning Plan to Counter Project Uncertainties,” Sloan Management Review 49, no. 2 (Winter 2008): 54–62.

4. Hollister B. Sykes and David Dunham, “Critical Assumption Planning: A Practical Tool for Managing Business Development Risk,” Journal of Business Venturing 10 (1995): 413–424.

5. The term learning loop comes from the Sykes and Dunham paper, as referenced in Chapter 4.