A Shortcut

The Answer Key is a tool for helping ensure you have the right answer to your root question. It works with the majority of organizational improvement questions. It will also give you ideas about other areas you may want to measure. You’ll get the most benefit when you use the Answer Key to work on organizational improvement efforts.

What Is the Answer Key?

The Answer Key can be used when your root question concerns the health of the organization. This covers a wide range of questions and needs we usually develop metrics for. Most root questions, especially in a business, revolve around how well the organization is functioning. Most Balanced Scorecards and questions about customer satisfaction fit under this umbrella.

The Answer Key is a shortcut for many of the metrics you’ll encounter. It includes the metrics I recommend organizations start with when they are seeking to implement a metrics program for the first time.

The Answer Key helps you determine where you need to go with your metrics. It also identifies other questions that may relate to the one you’re starting with. It can also help you keep from going in the wrong direction and dispersing your efforts too broadly, with no focus.

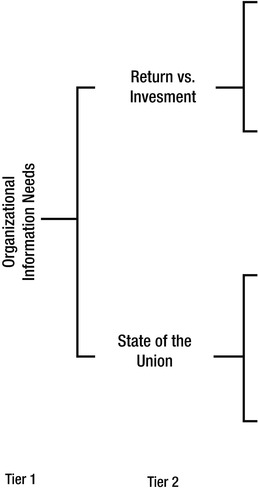

The Answer Key is made up of tiers that branch out from left to right. Each tier has more measures and data than the previous tier. The following sections will describe each of these tiers in more detail.

The first tier isn’t so much of a tier as it is a starting point. Is your root question an organizational information need? Does your root question deal with information about an organization; specifically, about the health of the organization? If so, your question will probably fall under one of the following two concerns:

- How well you provide services and products to your customers

- How healthy the future looks for your organization

If your root question fits within one of the first two tiers of the Answer Key, this tool will help you focus your efforts and find viable measures without spending inordinate amounts of time hunting for them. But, if your question does not fit into the Answer Key, don’t change your question so you can use this shortcut!

Also don’t ignore the need for developing the root question first. In other words, don’t start with the key. If you do, you’ll end up short-circuiting your efforts to develop useful metrics and more importantly, to answer your questions.

Tier two provides a framework for strategic-level root questions. If your root question is at the vision level, the second tier may represent actual metrics. When you find your root question is based on improving the organization, the question is often based on a need to understand “where the organization is” and “where it is going.” The Answer Key shows that this need for information flows into two channels, one to show the return (what we get) vs. our investment (what we put in) and the other to assist in the management of resources. I call these two branches “Return vs. Investment” and “The State of the Union.” Figure 5-1 shows this branching.

Figure 5-1. The Answer Key, tiers one and two

Return vs. Investment is the first of the two main branches of organizational metrics. It represents the information needed to answer questions concerning how well the organization is functioning and how well it is run. Are we doing the right things? Are we doing the right things the right way? These are key focus areas for improvement and, actually, for survival. If you aren’t doing the “right” things, chances are you will soon be out of business or, at the least, out of a job.

If you aren’t doing things the right way, you may find that you can continue to function and the business may continue to survive, but any meaningful improvement is highly unlikely. The best you will be able to hope for is to survive, but not thrive.

Root questions around the return may include

- How well are we providing our key services?

- In what ways can we improve our key services?

Questions around the investment may include

- How much does it cost us to provide our key services?

- How well are we managing our resources?

The breadth of your root question will determine how far to the left you’ll need to go. The farther left on the Answer Key, the more broad or strategic the question.

Once you are effectively and efficiently running the business, you can turn your attention to how you manage your resources. The most valuable assets you have should be maintained with loving care. Yes, I’m talking about your workforce. Every boss I’ve ever had has touted the same mantra: “Our most valuable assets are our people.” Yet it’s amazing to me how poorly we take care of those admittedly invaluable assets.

I observe managers who take their BMWs to their dealers for scheduled maintenance, only use premium gasoline (regardless of the price of gas), and won’t park anywhere near another car—yet do absolutely nothing to maintain their workforce. No training plans, no employee satisfaction surveys, not even a suggestion program. They rarely listen to their staff and devalue them by never asking for input. If people are truly our greatest assets, then we should treat them as such.

This view of the organization tells us how healthy our organization is internally. While Return vs. Investment tells us how healthy the organization is from a customer and business point of view, the State of the Union tells us how healthy the culture is.

Besides the workforce, we also need to focus on the potential for our future. We can determine this by looking at how we are managing our growth toward maturity. Do we have good strategic plans for our future? Are we working toward our goals?

Root questions you may encounter in this area include the following:

- How strong is the culture of recognition in our organization?

- How strong is the loyalty of our workforce?

- How well are our professional-development efforts working?

- What is the expected future of our organization?

- How do we stack up against our competition?

- How well are we achieving our strategic goals?

The further to the right you move on the Answer Key, the more specific and tactical your root questions will become.

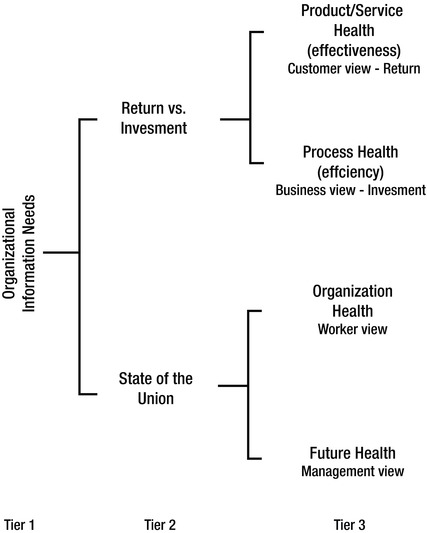

Figure 5-2 shows the next level of the Answer Key, in which we extend the branches to include Product/Service Health (effectiveness), Process Health (efficiency), Organizational Health (employee maintenance), and Future Health (projects and strategic planning).

Figure 5-2. The Answer Key, tiers one, two, and three

Most root questions boil down to wanting to know answers based on one of the views of the organization represented in the third tier. The titles—Product/Service Health, Process Health, Organizational Health, and Future Health—help us to understand the relationship of each branch to the other. They also help us understand where our metric fits. Along with the titles, we find an accompanying viewpoint to further assist in reading the Answer Key. These viewpoints show that each of the titles can be looked at from the perspective of Customers, the Business, the Workers, and finally Management.

Let’s figure out where your root question best fits.

Does your root question deal with how well you provide a service or product? Does it ask if you are doing the right things? Does it ask if the things you are doing satisfy the needs or desires of your customers? Is your root question one the customer would ask? If your question matches any of these, it fits into the Product/Service Health category.

Does your root question touch on how well you perform the processes necessary to deliver the services or products? How efficient you are? How long it takes or how much it costs for you to perform the tasks in the process? Is your question one a frontline manager would ask? If your question can be found in any of these, you are probably looking at a Process Health root question.

If your root question concerns human resources, the staff, or something a compassionate leader would ask, your question may belong in the Organizational Health branch. Root questions here ask about the morale of the workforce, loyalty, and retention rates for employees, among other things. How well do you treat your staff? Is your organization among the top 100 places to work in your industry?

The final area of the third tier represents root questions that are concerned with the Future Health of the organization. Is the organization suffering from organizational immaturity? How useful are the strategic plans, mission statement, and vision of the organization? How well is research and development progressing? This view is primarily one of top leadership—if your leadership and the organization are ready to look ahead.

How would you use the Answer Key to develop your metrics?

The information needed to define the Return vs. Investment is made up of the well-trod paths of “effectiveness” and “efficiency.” Effectiveness is the organization’s health from the customer’s point of view. How well is the organization delivering on its promises? Is the organization doing the right things? This is not only important for the development of viable metrics, but for understanding and growing the culture of the organization. Some organizations may not even know who its customers are. And if the customer base has been well defined, gathering the customer’s view of the components of effectiveness is not seen as important.

Sometimes organizations are forced to ask customers what they think of the company’s effectiveness. Surveys are built, focus groups are formed, and the questions are asked.

- Do you use our products or services?

- Are you satisfied with the delivery of our products and services?

- How satisfied are you with our organization?

While these questions help define viable measures, they also give focus for your own growth. Does the organization have a clearly-defined and documented list of customers? Does the organization know what its products and services are? Is the organization in the business of satisfying the customer? How does the organization “serve” the customer? These are more than guidelines for gathering data points. The Answer Key helps form a picture for an organization seeking to achieve continuous improvement.

While these four sections can describe the metrics themselves (if you have a higher-level root question), chances are your root question is at this level and your metrics won’t start until the fourth tier.

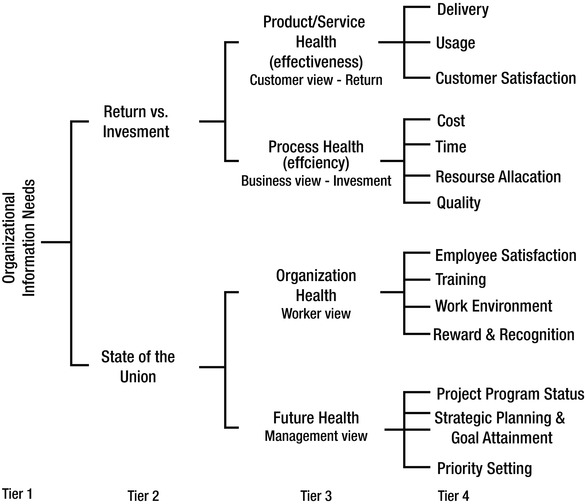

Now we’ll look at the level most organizations start and finish with. When your root question starts here, you have tactical, low-level questions. This is to be expected when an organization is first starting to use metrics. The root questions you’ll encounter will be very specific and may only address a small area. You may have a root question about delivery that asks, “How well are we responding to customers’ requests for updates?” for example.

You may have root questions around specific Process Health issues, like the amount of time it takes to produce a widget, the quality of your output, or the cost for a specific service. Where your root question falls in the Answer Key changes the character of each tier. Figure 5-3 introduces the fourth tier.

Figure 5-3. The Answer Key, tiers one through four

If your root question comes out of the fourth tier, everything to the left is context for the question. As your organization matures, you’ll move your questions to the left, asking questions from a more strategic position. If your root question were in tier two, then tier three would represent the metrics you could use and tier four would represent information. The measures and data would be defined for each information set—and could become a fifth and sixth tier if necessary.

The Answer Key not only keeps you focused and helps you determine what area you’re interested in; it also provides some standard metrics, information, and measures, depending on where your root question falls.

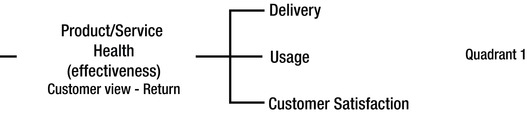

Product/Service Health (effectiveness)

The following are the main components of Product/Service Health (Figure 5-4):

- Delivery: How well are you delivering your products and/or services?

- Usage: Are your products and/or services being used?

- Customer satisfaction: What do your customers think of your products and/or services?

Figure 5-4. The Answer Key, Quadrant 1, Product/Service Health

Each component can be broken down into smaller bits—making it more palatable. Delivery is a good example for this as it is a higher-level concept. I tend to break delivery into the following parts:

- Availability: Is the service/product available when the customer wants it?

- Speed: How long does it take to deliver the service/product?

- Accuracy: Do we deliver what we say we will or are there errors involved?

The driving force behind Product/Service Health is the customer. We don’t care who is “responsible” for the issue. We don’t care if you have any control over the situation or condition. All we’re trying to see is how the customer views our products and services. This simplistic way of looking at your organization is valuable because it makes it easy to focus on what is most important.

The other component of Return vs. Investment is efficiency, or is the organization doing things the “right way?” This (Figure 5-5) captures a business view that all stakeholders should want to claim. The following, tested components of efficiency remain relevant:

- Cost: What is the cost-benefit of the way we perform our processes?

- Time: Time is akin to speed in the customer view. Many times the same data and sources can be reused for this measure. How much time does it take to perform a task or process?

- Resource allocation: How efficiently do we distribute the work? Do we assign work by type and amount?

- Quality: Quality is accuracy from the business point of view. Even if we have redundant systems providing 100 percent uptime, we will need to track that reliability (for each of those systems) so that we can best maintain them.

Figure 5-5. The Answer Key, Quadrant 2, Process Health

Many organizations focus too much on cost and forget that their concerns should first be based around whether the organization is doing the right things (effectiveness) and only then if it is doing them the right way (efficiency). Instead, many organizations latch onto any perceived faults in cost and then react without deep or critical thought. This error is compounded by the lack of information about the costs of services and production. This is especially noticeable in the soft industries. Manufacturing usually has a good handle on cost data, but soft industries like information technology, software development, or education find it very difficult to price out their products and services. This is logical, since these organizations normally have trouble defining what products and services they produce. Ask a dean of a given college what products and services the organization delivers. Then take a step further and see if the cost of those offerings is documented.

Time, especially when it is connected to cost as a delimiter (person/hours), is one of the most abused pieces of information. Managers jump on the metrics bandwagon when they start to believe that they can ask for data that will allow them to manage (not coach or lead) their people without having to actually talk to them or get to know them. Timesheets, time-motion studies, and time allocation worksheets come to be in vogue. In a well-constructed metrics program, you wouldn’t get to this level without starting from the all-important root and all of its listed components, which should prevent one from abusing the data. Time shouldn’t be used to “control” your workforce. It should be used to do the following:

- Improve the organization’s ability to estimate delivery schedules

- Assist in improving process and procedures

- Round out other data, like cost and quality

If “quality” is based on the objective measure of defects, how many defects per a thousand instances equals “quality?” Is high quality the goal? Is quality a “yes or no” decision? Quality is best described in terms of defects and rework, and like “time” it can be misused. It is not a simple way for managers to determine who should get a raise or any other human resources issue. If you abuse metrics, quality can become a weapon instead of a tool.

Ensure your metrics are used as a tool for improvement and not a weapon.

Quality, time, resource allocation, and cost are all components of Process Health and define the business view of the Investment the organization’s processes and procedures represent. Therefore, these views should only be used to improve the business—not people. Product/Service Health was exclusively from the customers’ viewpoint. Process Health is equally exclusive in its focus—and it represents the business view. The customer will most likely never see (and shouldn’t have a need to see) these metrics. These are “internal” metrics, as are the next two areas of the fourth tier.

Metrics should be used to improve the overall business, not people.

Organizational Health

When we look at Organizational Health (Figure 5-6), we look at the organization from the worker’s viewpoint. It takes into account the following:

- Employee satisfaction

- Professional development

- Work environment

- Reward and recognition

Figure 5-6. The Answer Key, Quadrant 3, Organizational Health

When we ensure that our most valuable assets are treated as such, we find that the organization improves. I normally suggest organizations address the Answer Key areas from the top down, making the Organizational Health measures third or fourth. This is in part due to political concerns. When you justify the use of metrics, it’s much easier to gain support if you first address the organization’s health from the customers’ point of view. Without customers, there won’t be a business to improve. Once you’ve tackled the customer’s view, you will need to ensure that you can afford to keep your workforce.

But in an ideal world, one in which perhaps you are the CEO, I’d argue easily that the first place to start your improvement efforts should be with your greatest assets, and then with your customers. Sound blasphemous? If you have a healthy workforce, you can work with them to better define your business model, your future, and where you want to improve.

Employee satisfaction is pretty straightforward. The more satisfied your workforce is with their situation, the organization, and the environment, the harder they will work. The more loyal they will be. The stronger your organization will become.

Along with their satisfaction, you must be concerned with developing their skills and their knowledge base. Professional development measures tell you how well you’re doing in this area. Do you have training plans for each worker? What is the level of skill development for each worker? The stronger your workforce, the more you’ll be able to do. It should be a criminal offense to first eliminate training whenever funding cuts come down. The only way to do more with less is to increase the capacity of our workforce to produce more and produce better. The best way to improve productivity is to improve the worker’s skill set.

The work environment measures are normally captured through subjective tools—like surveys. But there are plenty of objective measures available. Square footage for workspace. Air quality. Lighting. Ergonomics. There are many ways to measure the quality of the physical work environment. There is also the cultural work environment. Is the organization a pleasant place to work? Is it a high stress environment (and if it is, does it need to be)? Again, you can find both subjective (ask the workers) and objective measures. Do workers take a lot of vacation and sick time? Is turnover high?

The final component of Organizational Health is reward and recognition. The simple questions may not require data collection. Do you have a formal reward or recognition program? Is it effective? Does it do what you want it to? How do you reward your workers? How do you recognize their accomplishments? Do you only recognize their work-related achievements? And on a more subtle note, do you inadvertently combine recognition and reward, such that recognition only occurs when there is a reward involved?

The bottom line on Organizational Health is an extremely easy one—do you treat your most valuable asset like they are your most valued asset?

Future Health

The last area of the Answer Key is Future Health (Figure 5-7). It covers the following:

- Project/Program status

- Strategic planning: How well the organization is implementing the strategic plan

- Goal attainment: How well the organization is reaching its goals

- Priority setting: How well priorities are being set, and being met

Figure 5-7. The Answer Key, Quadrant 4, Future Health

This area assumes that you are working on continuous improvement for the organization. Future Health is not listed last because it isn’t as important as the others. It’s last in the list because most organizations are not ready for attempting metrics in this area. Most organizations need to get the first three areas of the fourth tier under control before they start to look at large-scale improvement efforts.

Many organizations bypass this guidance and jump to measures to show how well they are working to improve processes. They jump on the continuous process improvement wagon. I don’t put much faith in such behaviors since these organizations drop these same efforts as soon as funding becomes tight.

The reason you undertake an improvement effort is more important than if you succeed at it. The only way you can truly succeed is to do the right things for the right reasons.

Measures around the organization’s Future Health are mostly predictive, and this makes them “sexy” to leadership. But more important than predicting the future is encouraging and rewarding true process improvement.

Program and project status measures provide insights for leadership into how these efforts are helping improve the organization. You should expect that progress in process improvement is or will be reflected in the measures captured in the other three areas. If you do a good job on continuous process improvement, the customer view should improve. The business view should also see gains, and the workforce should also benefit. If these three areas aren’t improved by your efforts, you aren’t improving the organization.

Strategic planning, goal attainment, and priority setting are all important things to focus on—but in themselves they are meaningless. If these are not part of a bigger effort to improve the organization, you are just spinning your wheels. These efforts are tough because they require true (and sometimes reckless) commitment to succeeding. You have to want to change. Many organizations pay lip service to this area and don’t really see the effort through to the end—and when we’re talking about “continuous” process improvement—there really isn’t an end.

Answer Key: The Fifth Tier and Beyond

The fifth tier would introduce specific measures for each of the “information” within each of the viewpoints presented. While your root question could conceivably be here, it is unlikely. If you find your question starts here, you probably don’t have a need for a metric. Instead, you probably only need a measure.

The elements you’re most likely to find here are measures. For example, extending from the top branch of Usage in the fourth tier you may find the following branching out into a fifth tier:

- Unique customers by month, by type

- Number of purchases, by type

- Number of repeat customers

It is unnecessary to list possible measures for each of the fourth tier’s elements. It won’t make any sense to try to list each of what would be in tier six or seven—lower-level measures or data. In the examples for Usage, we might see data points as follows:

How to Use the Answer Key: Identify Types of Measures

The Answer Key can be used to identify measures you can use to answer your root question. If you have done your homework and defined the root question and developed your abstract design, you are now ready for the next step—identifying possible measures to fill out the metric.

The Answer Key can help with this phase of the process. Take your root question and metric design and determine where you are on the Answer Key. If your question deals with the value of the organization, then you’re on the top tier, Return vs. Investment. If your question is in the realm of managing organizational resources, you’re on the lower tier, State of the Union.

We used some examples of root questions earlier. One was based on the distribution of work. This would fit under the fourth tier, Process Health–Resource Allocation. Using this tool, we not only can identify the type of measures we’ll need, but we understand the area of focus of our question. Moving to the left from Resource Allocation, we can see that our question is dealing with the business view (investment). If our question is a root question, we can use the Five Whys. And now we can also ask if our concerns are bigger than just Resource Allocation (measure centered). Are our concerns actually around Process Health? Are we missing the measures around cost, time, and quality?

If your root question is answered by just one of the measures in the fourth tier, chances are you don’t have the root question. You definitely don’t have a metric.

Using the Answer Key allows us to do a quick and easy quality check on the measures we’ve identified. For example, if the metric is a Worker view (based on the root question), and you find some of the measures you identified are from the Customer view (like delivery measures), then either those measures are wrong for the metric, or, possibly your metric is not the right one for answering the question. As a general rule, I find that the measures are usually misplaced, rather than that the metric is incorrect.

Using the concept of triangulation is essential to creating effective metrics. I bow to Norman K. Denzin, a professor of communications and sociology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, for his using “triangulation” to mean using more than two methods to collect data in the context of gathering and using research data. My definition is much like it—using multiple measures, as well as collection methods, for processing the information used in a metric.

A major reason for using triangulation, according to Denzin, is to reduce (if not eliminate) bias in the research. By using triangulation we ensure that we have a comprehensive answer to the question.

You may have noticed that at the fourth tier of the Answer Key, there were always a minimum of three measures. This is because of triangulation.

Denzin offers that as you increase the number of differing measures used to provide insight on a single issue, the definitions move from an abstract thought, to validated concept, and finally to proven reality. Although Denzin may not have been the first to coin the term “triangulation”—he cites Eugene J. Webb as the father of the term—I like his explanation. It matches very closely to how I use the term in the context of a metrics program.

If you take the time to research Denzin’s use of triangulation, you’ll find that it isn’t an exact match to how I use the term for metrics. That is partly due to the nature of the use of our results. While Denzin is giving guidance for sociological research that has the purpose of finding deeper truths within his field and having those truths debated and challenged within the scientific community in journals and experiments—our needs (yours and mine) are much simpler and more practical.

When I created a metrics program for my organization in 2003, I started with the Product/Service Health quadrant (Effectiveness). Yes, I practiced what I preached.

I knew the quadrant. I knew the possible measures that would fit (or at least a starting point). I also knew how to test the measures for alignment with the Product/Service Health quadrant.

But to ensure we gained a comprehensive picture, I fell upon triangulation—the use of three or more measures to answer the question. In the case of effectiveness, we identified the primary measures—Delivery, Usage, and Customer Satisfaction—from the Answer Key.

Rather than select one or two, I determined that we should use all three, which would provide a fuller picture. Each measure had different characteristics in their sources and methods of collection.

Triangulation of Collection Methods and Sources

Triangulation also requires different collection methods, as follows:

- Delivery is an objective (quantitative) internal measure collected without customer involvement. Most times I was able to use automated collection methods for these measures (like trouble call tracking systems, monitoring systems, or time accounting systems). These do not measure customers, but how well the organization delivers the products and services.

- Usage is an objective (quantitative) external measure based on customer behaviors. What do they buy? Who do they call? How often do they use our services? How did they find out about our services and products? How many one-time customers do we have vs. how many repeat customers?

- Customer Satisfaction is a subjective (qualitative) external measure and the most customer-centric of the group. Here, we directly ask the customer for their opinion. A better title for this item would be “customer direct feedback.” You ask the customer what they thought of the service and product, but you also ask for ideas for improvement. These questions can be asked in a survey, through focus groups, or through individual interviews. There are pros and cons to each, from varying costs to differing volumes of data collected. You should pick the methods that work best for you. Many times the customer base will dictate the best feedback tools.

You can use other groupings for triangulation. I offer these because I know they work, and they are simple to implement. The idea is to address at least three different viewpoints, sources, and methods of collection.

The concept of triangulation can be used at each level of the metric. I don’t suggest you go too deeply or you may find that you are collecting thousands of different measures. I want you to use triangulation at the top level—in the case of effectiveness metrics, at the Delivery, Usage, and Customer Satisfaction level. But, you can use the same concept at the next level down.

For Customer Satisfaction, you could use the following three different methods of collection: surveys, focus groups, and interviews. This can be very expensive, especially interviews. But you could also use two different surveys—the annual survey given to a large portion of your customer base, and the trouble call survey.

You get the idea.

Another example is Delivery. We actually broke Delivery out into three major factors:

- Availability

- Speed

- Accuracy

Each of these were looked at for possible triangulation. Did we have three good ways to measure Availability? How about Speed? Yes. Speed to deliver, speed to resolve, speed to respond for example.

One last way to look at triangulation is through perspectives. We’ve actually already included this in our three areas of measure. Remember? Delivery was an internal perspective. Usage and Customer Satisfaction were external. There are only two choices here, but when we add in the subjective and objective qualifiers we have a total of four possible choices.

We used only three—external objective, external subjective, and internal objective. Since that early program in 2003, I have since chosen to add a fourth measure area to the Effectiveness quadrant. You may have noticed that we are missing an internal subjective measure. We had the other three permutations, but we never thought to ask the service providers what they thought of the service they were providing.

Remember, you don’t have to stop at three. You should use as many different measures, collection methods, sources, and perspectives as necessary to tell the complete story.

Because we use varying methods and data sources, we run the real risk of obtaining conflicting results. But, rather than see this as a negative, you should see it as a positive.

Let’s look at a restaurant example. If our restaurant’s effectiveness metric is made up of Delivery, Usage, and Customer Satisfaction, we may expect that the results of each of these measurement areas should always coincide. If we have good service (Delivery) we should have high Customer Satisfaction ratings. And if we have high Customer Satisfaction, we could assume that we should have high levels of repeat customers, and high usage. We also expect the opposite. If we have poor Customer Satisfaction, we expect that customers won’t come back. If we don’t deliver well (too slow, wrong items delivered, or the menu items are unavailable) we would expect poor ratings and less usage.

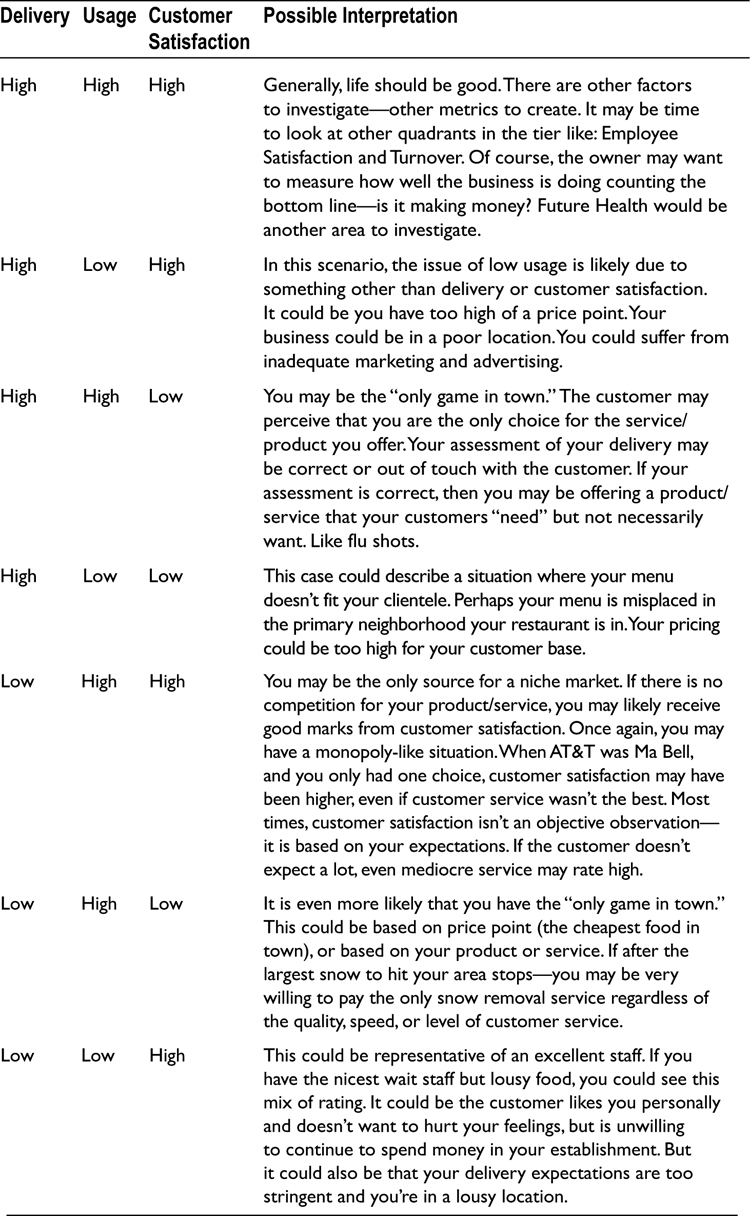

These are logical assumptions, but many times incorrect ones. Each of the permutations tells us something different. In Table 5-1, let’s look at each measure with a simple high vs. low result. Of course, the real results of your measures may be much more complicated—especially when you remember that each can also utilize triangulation. Delivery could have high availability and speed to deliver, but poor accuracy. You could have high usage for one type of clientele and low for another. Customer satisfaction could have high marks for some areas (courtesy of staff) and low for others (efficiency of staff). Rather than complicate it further, let’s look at the measures at the higher level, keeping in mind the complexity possible when taking into account lower levels of triangulation.

Table 5-1. Interpreting Measures: An Example

Besides the interpretation of each of the individual measurement areas, the triangulation itself offers information you would lack if you only collected one or two areas.

Using our restaurant business as an example, let’s interpret some possible measures. In Table 5-1, you can see how different permutations of the results of the measures can tell a different story. While each measure provides some basic insights, it is more meaningful to look at them in relation to each other.

You may argue that triangulation seems to make the results more confusing, not clearer. But in actuality, triangulation assures that you have more data and more views of that data. The more information you have the better your answers will be. But in all cases the next step should be the same. Investigate, investigate, investigate. The beauty of triangulation is that you already have so many inputs that your investigation can be much more focused and reap greater benefits with less additional work.

Imagine if all you measured was Customer Satisfaction. If you ratings in this area were high, what could you determine? You could think life was good. But if you’re not making enough money to keep your business open, you’ll wonder what happened.

Triangulation not only allows you to use disparate data to answer a single question, it actually encourages you to do so.

Recap

The Answer Key can help you check the quality of your work and ensure that you’re on the right track. And if or when you get stumped and you don’t know which direction to go, it can help you get on track.

Most metrics you design, if they fall on the Answer Key, will most likely start at the third tier and belong to one of the following four viewpoints:

- The customers’ viewpoint (effectiveness)

- The business’s viewpoint (efficiency)

- The workers’ viewpoint

- The leadership’s viewpoint

As you move from left to right on the Answer Key, you move from the strategic to the tactical. Another way to look at this is that you move from the root question toward data.

Regardless of where your metric (or root question) falls, you’ll have to move to the right to find the measures and data you need to answer the question. At the fourth tier we found the following:

- Return vs. Investment

- Product/Service Health—Customer View

- Process Health—Business View

- State of the Union

- Organizational Health—Employee View

- Future Health—Leadership View

The fourth tier is the most frequently used by my clients. It is far enough left that root questions starting here are worthy of metrics to answer, and far enough right that they are easy for most organizations to comprehend their use in improving the organization.

In the fifth (and any consecutive) tier, we find mostly information and measures. If we find our root question residing here, the question is probably very tactical and may not require a full-blown metric to answer. Remembering the Metric Development Plan, you should flesh out the metric by identifying not only the information and measures, but also document the individual data points needed.

Triangulation is a principal foundation for a strong metric program. Triangulation has many benefits. The more triangulation used, the stronger the benefits. But the saying “all things in moderation” is also true with triangulation. You can overdo anything. You’ll need to find the happy medium for you. Let’s look at some of the following benefits:

- Higher levels of confidence in the accuracy of the measures used to form the metric

- Higher levels of confidence in the methods used to collect, analyze, and report the measures

- A broader perspective of the answer—increasing the likelihood of an accurate interpretation of the metric

- Satisfaction in knowing that you are “hearing the voice of all your customers”

- A more robust metric (if you lose a measure, data source, or analysis tool, you will have other measures to fall back on)

- Confidence that you are “seeing” the big picture as well as you can

It is important to use triangulation in more than one aspect of the measurement collection and analysis, including the following:

- Multiple sources of data

- Multiple collection methods

- Multiple analysis methods (across measures and the willingness to apply different analytics to the same measures)

- Multiple areas (like Delivery, Usage, and Customer Satisfaction) or categories

With all of this diversity, it is important to stay focused. Collecting data from different quadrants in the Answer Key would not fit the principle of triangulation. If you dilute your answers by mixing the core viewpoint, you will run the risk of becoming lost in the data. If you lose focus and collect data from disparate parts of the Answer Key, it is probable that you are trying to answer multiple questions with only one answer. While meta-metrics use other metrics as part of their input, they must still stay within the context defined by the root question.

A solid metric can lead you in time to metrics in other areas of the Answer Key, but only after you’ve done your due diligence in answering the questions at hand.