Designing and Documenting Your Metrics

The How

Now that we have a common language, the next step is to discuss how to proceed. I’ve read numerous books, articles, and blog posts on Balanced Scorecards, Performance Measures, and Metrics for Improvement. I haven’t found one yet that puts “how to develop a metric from scratch” into plain English. It’s about time someone did.

In this chapter we’ll cover the following:

- How to form a root question—the right root question

- How to develop a metric by drawing a picture

- How to flesh out the information, measures, and data needed to make the picture

- How to collect data, measures, and information

This may seem like a lot of work (and it is), but I guarantee you that if you follow this method you will save an enormous amount of time and effort in the long run. Most of your savings will come from less rework, less frustration, and less dissatisfaction with the metrics you develop.

Think of it this way: You can build a house by first creating a blueprint to ensure you get the house that you want. Or you can just order a lot of lumber and supplies and make it up as you go along. This process doesn’t work when building a house or developing software. It requires discipline to do the groundwork first. It will be well worth it. I’ve never seen anyone disappointed because they had a well thought-out plan, but I’ve helped many programmers try to unravel the spaghetti code they ended up with because they started programming before they knew what the requirements were.

While programmers have improved at upfront planning, and builders would never think to just start hammering away, sadly those seeking to use metrics still want to skip the requirements phase.

So let’s start working on that blueprint.

Before you can design a metric, you have to first identify the root question: What is the real driving need? The discussion I’ve had many times with clients often goes like the following dialog (in which I’m the metrics designer):

Director: “I’d like to know if our service desk is responsive to our customers.”

The first clue that the metrics designer has to dig deeper for the real root question is that the answer to the given question could be yes or no.

Metrics Designer: “What do you mean by responsive?”

Director: “Are we answering calls in a timely manner?”

Metrics Designer: “What exactly is a ‘timely manner’? Do you mean how many seconds it takes or how many times the phone rings?”

Director: “I guess within the first three rings?”

The designer made a note—that the director guessed calls should be answered within three rings, but that end users had to provide the actual definition of “responsiveness.”

Metrics Designer: “Okay. Why do we need to know this? What’s driving the curiosity?”

Director: “I’ve had some complaints that we aren’t picking up the phone quickly enough. Customers say they can’t reach us or they have to wait too long to get to speak to a person.”

Metrics Designer: “What constitutes ‘not quick enough’? Or, what is a wait that is ‘too long’?”

Director: “I don’t know.”

The designer made some more notes. The director was willing to admit that he didn’t know what the customer meant by “quick enough” and that he didn’t know what would please the customer. This admission was helpful.

Metrics Designer: “I suggest we ask some of your customers to determine these parameters. This will help us determine expectations and acceptable ranges. But we also need to know what you want to know. Why do you want to know how responsive the service desk is?”

Director: “Well, the service desk is the face of our organization—when most customers say ‘Emerald City Services’ they think of the service desk.”

Metrics Designer: “So, what do you want to know about the face of your organization?”

Director: “How well it’s received by our customers. I want to know if it’s putting forth a good image.”

This is a much better starting point for our metric design. With the root question (How well is the service desk representing Emerald Services?) we can decide on a more meaningful picture—a picture that encompasses everything that goes into answering the question.

There are other possible results of our inquisition. Our job is to reach the root question. We have to help our clients determine what their real underlying needs are and what they need or want to know. One tool for doing so is the Five Whys.

The Five Whys is simple in its concept. You ask “why” five times, until the client can no longer answer with a deeper need. Of course, you can’t ask “why” repeatedly like a child being told they can’t play in the rain. You have to ask it in a mature manner. Many times you don’t actually use the word, “why.” As in the earlier example, sometimes you ask using other terms—like “what” and “how” and “what if?”

The process isn’t so much predicated on the use of the word “why” as it is grounded in attempting to reach the root purpose or need. Perhaps the worst error is to jump happily at the first “why” in which you feel some confidence that you could answer. We are all problem solvers by nature, and the possibility of latching onto a question with which we can easily provide an answer is very tempting.

Start with Goals

If you don’t have a list of goals for your unit, you can add value by first developing them. This may seem to be outside of the process for designing metrics, but since you must have a good root question to move forward, if you have to create metrics around goals, you don’t have any choice.

If you have a set of goals, then your task becomes much easier. But be careful; the existence of a documented strategic plan does not mean you have usable goals. Unless you have a living strategic plan, one that you are actually following, the strategic plan you have is probably more of an ornament for your shelf than a usable plan. But, let’s start with the assumption that you’ll have to identify your goals, improvement opportunities, and/or problems.

The best way I’ve found to get to the root questions when starting from a blank slate is to hold a working session with a trained facilitator, your team, and yourself. This shouldn’t take longer than two or three one-hour sessions.

When building metrics from a set of goals, work with the goals (as you would a root question) to get to the overarching goal. Many strategic plans are full of short- to mid-range goals. You want to get to the parent goal. You need to identify the long range goals, the mission, and/or the vision. You need to know why the lower-level goals exist, so that if the strategic plan doesn’t include the parent goal, you’ll have to work with the team to determine it. Again, the Five Whys will work.

We’ve discussed using five “whys” to get to a root need and to get to driving goal behind a strategic plan. However, any method for eliciting requirements should work. The important thing is to get to the underlying need. The root question should address what needs to be achieved, improved, or resolved (at the highest level possible).

What’s important to remember is that you can work from wherever you start back to a root question and then forward again to the metric (if necessary). I told a colleague that I wanted to write a book on metrics.

“Why? Don’t you have enough to do?” She knew I was perpetually busy.

“Yes, but every time I turn around, I run into people who need help with metrics,” I answered.

“Why a book?” She was good at The Five Whys.

“It gives me a tool to help teach others. I can tell them to read the book and I’ll be able to reference it.”

“So, you want to help others with designing metrics. That’s admirable. What else will you need to do?”

And that started me on a brainstorming journey. I captured ideas from presenting speeches, teaching seminars and webinars, to writing articles and proposing curriculum for colleges. I ended up with a larger list of things to accomplish than just a book. I also got to the root need and that helped me focus on why I wanted to write the book. That helps a lot when I feel a little burned out or exhausted. It helps me to persevere when things aren’t going smoothly. It helps me think about measuring success, not based on finishing the book (although that’s a sub-measure I plan on celebrating) but on the overall goal of helping others develop solid and useful metrics programs.

Once you think you have the root question, chances are you’ll need to edit it a little. I’m not suggesting that you spend hours making it “sound” right. It’s not going to be framed and put over the entrance. No, I mean that you have to edit it for clarity. It has to be exact. The meaning has to be clear. As you’ll see shortly, you’ll test the question to ensure it is a root—but beforehand it will help immensely if you’ve defined every component of the question to ensure clarity.

Define the terms—even the ones that are obvious. Clarity is paramount.

Keep in mind, most root questions are very short, so it shouldn’t take too much effort to clearly define each word in the question.

As with many things, an example may be simpler. Based on the conversation on why I wanted to write this book, let’s assume a possible root question is: How effective is this book at helping readers design metrics? You can ensure clarity by defining the words in the question.

- How effective is this book at helping readers design metrics?

- What do we mean by effective? In this case, since it’s my goal, I’ll do the definitions.

- The how portion means, which parts of the book are helpful? Which parts aren’t? Also, does it enable someone to develop high-quality metrics? After all, my goal is to make this book a practical tool and guide for developing a metrics program. “How well can the reader design metrics after reading the book?

- How effective is this book at helping readers design metrics?

- Do we really want to measure the effectiveness of the book or is there something else you want to measure?

- Even obvious definitions, like this one—may lead you to modify the question. If asked, “What do you mean by this book?” I might very well answer, “Oh, actually I want to know if the system is effective, of which the book is the vehicle for sharing.” This would lead us to realize that I really wanted to know if my system worked for others—more so than if this form of communication was effective.

- How effective is this book at helping readers design metrics?

- Does it help? I have to define if “help” means

- Can the reader develop metrics after reading it?

- Is the reader better at developing metrics after reading it?

- Does the reader avoid the mistakes I preach against?

- Readers are another obvious component—but we could do some more clarification.

- Does “reader” mean someone who reads the “whole” book or someone who reads any part of the book?

- Is the reader based on the target audience?

- Does it help? I have to define if “help” means

- How effective is this book at helping readers design metrics?

- What do I mean by “design”? As you have read, for me designing a metric involves a lot more than the final metric. It includes identifying the root need and then ensuring a metric is the proper way to answer it. So, while “design” may mean development, it has to be taken in the context of the definition of a metric.

- What do I mean by metric? Do I mean the metric part of the equation or does it include the whole thing—root question, metric, information, measures, and data? If you’d read the book already, you’d know the answer to this question. The metric cannot be done properly without the root question, and is made up of information, measures, data, and other metrics. Even with that—what I mean in the root question may be a little different than this because the outcome of following the process may be to not create a metric. In that case, using the root question to provide an answer would be a success—although no metric was designed.

Based on this exercise, if I chose to keep the root question the same, I’d now know much better how to draw the picture. Chances are though, after analyzing each word in the question, I would rewrite the question. The purpose behind my question was to determine if the book was successful. And since success could result in not designing metrics, I would rewrite my question to be more in tune with what I actually deem success—the effective use of my system. The new root question might be: How effective is my system in helping people who want or need to design metrics?

If you think you’ve got the root question identified, you’re ready to proceed. Of course, it may be worthwhile to test the question to see if you’ve actually succeeded.

Test 1. Is the “root” question actually asking for information, measures, or data? “I’d like to know the availability of system X.” This request begs us to ask, “Why?” There is an underlying need or requirement behind this seemingly straightforward question. When you dig deep enough, you’ll get to the real need, which is simply a request for data. The root question should not be a direct request for data. The following are examples of requests for data: Do we have enough gas to reach our destination? Is the system reliable or do we need a backup? How long will it take to complete the project?

Test 2. Is the answer to the question going to be simple? Is it going to be a measure? Data? If the answers are either “yes” or “no,” chances are you’re not there yet or the question doesn’t require a metric to provide an answer. It may seem too easy—that you wouldn’t get questions after all this work that could be answered with a yes or no. But, it happens. It may mean only a little rework on the question, but that rework is still necessary. Is our new mobile app going to be a best seller? Should we outsource our IT department? Are our employees satisfied? These may seem like good root questions, but, they can all be answered with a simple yes or no.

Test 3. How will the answer be used? If you’ve identified a valid root question, you will have strong feelings, or a clear idea of how you will use the answer. The answer should provide discernible benefits. Let’s take my question about the effectiveness of this book at helping readers develop metrics. If I learn that it’s highly effective at helping readers, what will I do? I may use the information to gain opportunities for speaking engagements based on the book. I may submit the book to be considered for a literary award. I may have to hold a celebration. If the answer is that the book is ineffective, then I may investigate possible means of correcting the situation. I may have to offer handbooks/guidelines on how to use the book. I may have to offer more information via a web site. If the feedback is more neutral, I may look at ways to improve in a later edition.

The key is to have predefined expectations of what you will do with the answers you’ll receive. When I ask a client how they’ll use the answer, if I get a confused stare or their eyes gloss over, I know we’re not there yet.

Test 4. Who will the answer be shared with? Who will see the metric? If the answer is only upper management, then chances are good that you need to go back to the drawing board. If you’ve reached the root question, many more people should benefit from seeing the answer. One key recipient of the answer should be the team that helped you develop it. If it’s only going to be used to appease upper management—chances are you haven’t gotten to the root or the answer won’t require a metric.

Test 5. Can you draw a picture using it? When you design the metric, you will do it much more as an art than a science. There are lots of courses you can take on statistical analysis. You can perform exciting and fun analysis using complex mathematical tools. But, I’m not covering that here. We’re talking about how to develop a useable metrics program—a tool for improvement. If you can’t draw a picture as the answer for the question, it may not be a root question.

Not all root questions will pass these tests.

I’m not saying that all root questions must pass these tests. But, all root questions that require a “metric” to answer them must. If your question doesn’t pass these tests, you have some choices.

- Develop the answer without using data, measures, information, or metrics. Sometimes the answer is a process change. Sometimes the answer is to stop doing something, do it differently, or start doing something new. It doesn’t have to result in measuring at all.

- Develop the answer using measures (or even just data). This may be a one-time measure. You may not need to collect or report the data more than once.

- Work on the question until it passes the five tests—so you can then develop a metric. Why would you want to rework your question simply to get to a metric? You shouldn’t. If you feel confident about the result, stop. If the client says you’ve hit upon the root question, stop. If the question resonates fully, stop. Wherever you are, that’s where you’ll be. Work from there. Don’t force a metric if it’s not required.

Your task is not to develop a metric—it’s to determine the root question and provide an answer.

It’s an interesting argument: is the process of designing metrics a science or an art? If you read statistics textbooks, you might take the side of science. If you read Transforming Performance Measurement: Rethinking the Way We Measure and Drive Organizational Success by Dean Spitzer (AMACON, 2007), or How To Measure Anything by Douglas Hubbard (Wiley, 2010), you might argue that it’s an art. I propose, like most things in real life (vs. theory), it’s a mixture of both.

One place it’s more art than science is in the design of a metric. I can say this without reservation because to design our metric, you want to actually draw a picture. It’s not fine art. It’s more like the party game where you’re given a word or phrase and you have to draw a picture so your teammates are able to guess what the clue is.

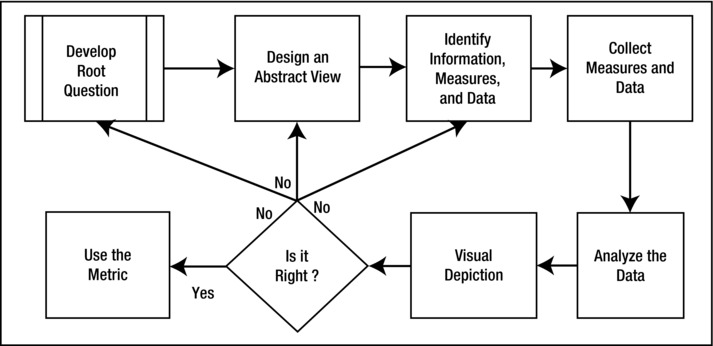

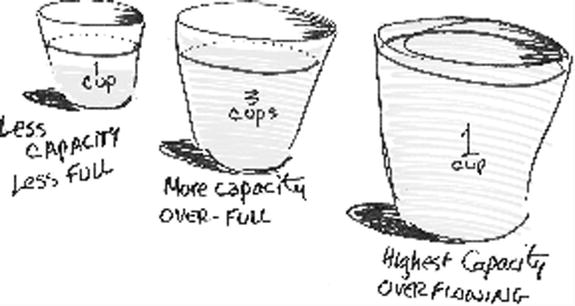

At the first seminar I taught on designing metrics, “Do-It-Yourself Metrics”, I broke the students into groups of four or five. After stepping through the exercise for identifying root questions, I told them to draw a picture to provide an answer to a question. The question was, “How do we divide our team’s workload to be the most productive?” Figure 3-1 shows the best of the students’ answers.

Figure 3-1. Workload division metric

This picture shows how each person (represented by a different cup) has different levels of work. The level of the liquid represents the amount of work “in each person’s cup.” The line near the top is the highest level the liquid should be poured to, because the froth will cause it to overflow. This line represents the most each person can actually handle, leaving room at the top for the “extra”—like illness, lunch, vacation, etc. By looking at the picture, the manager gets an easy-to-understand story of who has too much work, who can take on more, who is more productive, and who needs to improve their skill sets so that they can eventually have a larger cup.

A useful part of drawing the picture was clarity around the question. To ensure that we drew it right, we needed to also define the terms we were using in the picture: productivity, workload, and team.

Define the terms—even the ones that are obvious. Here too, clarity is paramount.

We found out that workers A, B, and C made up the team—they did the same type of work in a small unit of the organization. We also learned that the word “team” didn’t mean that the group normally worked together. On the contrary, this “team” worked independently on different tasks. This simple realization gave the manager more ideas.

Workload was defined as the tasks given to the workers by the manager. It excluded many other tasks the workers accomplished for other people in the organization, customers, and each other. The only tasks that counted in this picture were the ones with deadlines and accountability to the management chain.

Productivity was defined as how many tasks were completed on time (or by the deadline).

These definitions are essential to developing the “right” metric. We could have drawn a good picture and designed a metric without these clarifications, but we would have risked measuring the wrong things.

Don’t assume the terms used in the question are understood.

The metric would also be useful later, when the manager provided training opportunities for the staff. If the training did what was expected, the cups would increase in size—perhaps from a 32-ounce to a 44-ounce super size.

Does this seem strange? Does it seem too simple?

While I can’t argue against things being “strange,” very few things are ever “too simple.” Einstein once said, “Make it as simple as possible, but no simpler.” This is not too simple—like Goldilocks was fond of saying, “it’s just right.”

Once we have clear definitions for the terms that make up the root question, we will have a much better picture! Remember the importance of a common language? It is equally important that everyone fully understands the language used to create the root question.

I work with clients to modify these drawings until it provides the full answer to their question. This technique has excellent benefits. By using a picture:

- It’s easier to avoid jumping to data. This is a common problem. Remember the natural tendency to go directly to data.

- It’s easier to think abstractly and avoid being put in a box. Telling someone to “think outside the box” is not always an effective way to get them to do so.

- We avoid fears, uncertainty, or doubt about the ability to collect, analyze, and report the necessary information. These common emotions toward metrics restrict your ability to think creatively and thoroughly. They tend to “settle” for less than the ideal answer.

- We have a non-threatening tool for capturing the needs. No names, no data or measures. No information that would worry the client. No data at all. Just a picture. Of course this picture may change drastically by the time you finalize the metric. This is essentially a tool for creatively thinking without being restricted by preconceptions of what a metric (or what a particular answer) should be.

One key piece of advice is not to design your metric in isolation. Even if you are your own metric customer, involve others. I am not advocating the use of a consultant. I am advocating the use of someone—anyone—else. You need someone to help you generate ideas and to bounce your ideas off of. You need someone to help you ask “why.” You need someone to discuss your picture with (and perhaps to draw it). This is a creative, inquisitive process—and for most of us, it is immensely easier to do this with others. Feel free to use your whole team. But don’t do it alone.

A good root question will make the drawing easier.

Having a complete picture drawn (I don’t mean a Picasso) makes the identification of information, measures, and data not only easy, but ensures you have a good chance of getting the right components.

The picture has to be “complete.” After I have something on paper (even if it’s stick figures), I ask the client, “what’s missing?” “Does this fully answer your question?” Chances are, it won’t. When I did the conference seminar, the team members had cups—but they were all the same size and there was no “fill-to-here line.” After some discussion and questioning, the group modified the drawing to show the full story.

It’s actually fun to keep modifying the picture, playing with it until you feel it is complete. People involved start thinking about what they want and need instead of what they think is possible. This is the real power of drawing the metric.

Identifying the Information, Measures, and Data Needed

Only after you have a complete picture do you address the components. This picture is an abstract representation of the answer(s) to our root question. It’s like an artist’s rendition for the design of a cathedral—the kind used in marketing the idea to financial backers. When you present the idea to potential donors, you don’t need to provide them with blueprints, you need to pitch the concept.

Next are the specific design elements to ensure the building will be feasible. As the architect, you can provide the artist’s conception and do so while knowing from experience whether the concept is sound. Your next step is to determine what will go into the specific design—the types of structures, wiring, plumbing, and load-bearing walls. Then you will have to determine the materials you need to make it a reality—what do we need to fill in the metric?

Let’s look at the workload example. How do we divide our team’s workload to be the most productive? Remember, the picture is of drink cups—various sizes from 20-ounce, to 32-ounce, to a super-sized 44-ounce. Each cup has a mark that designates the “fill” level—and if we fill above this line, the froth will overflow the cup. Using the picture, we need to determine the following:

- How do we measure our team’s level of productivity?

- How do we currently allocate (divide) the work?

- What are other ways to allocate the work?

Of the three pieces of information listed, only the first seems to need measures. The other two are process definitions. Since our question is driven by a goal (to improve the team’s productivity), the process for designing the metric will produce other useful elements toward the goal’s achievement.

Information can be made up of other information, measures, and data. It isn’t important to delineate each component—what’s important is to work from the complex to the simple without rushing. Don’t jump to the data!

An example of how you can move from a question to measures and then to data follows.

- How do we measure our team’s level of productivity?

- How much can each worker do?

- Worker A?

- Worker B?

- Worker C?

- How much can each worker do?

- How much does each worker do?

- By worker (same breakout as the previous measure)

- How much does each worker have in his or her cup?

- By worker

- How long does it take to perform a task?

- By worker

- By type of task

- By task

I logged a sub-bullet for each worker to stress what seems to be anti-intuitive to many people—most times there is no “standard” for everyone. When developing measures, I find it fascinating how many clients want to set a number that they think will work for everyone.

Machinery, even manufactured to painstakingly precise standards, doesn’t function identically. Why do we think that humans—the most complex living organism known, and with beautiful variety—would fit a standardized behavior pattern?

Of course it would be easier if we had a standard—as in the amount of work that can be done by a programmer and the amount of work each programmer does. But this is unlikely.

You may also be curious why we have the first and second measures—how much a worker can do and how much he accomplishes. But since the goal is to increase the productivity of the team, the answer may not be in reallocating the load—it may be finding ways to get people to work to their potential. A simpler reason is that we don’t know if each worker is being given as much as they can do—or too much.

Looking back at Figure 3-1, we may need to decide if the flavor of drink matters. Do we need to know the type of work each worker has to do? Does the complexity of the work matter? Does the customer matter? Does the purpose of the work matter? Does the quality of the work matter? Should we only be measuring around the manager’s assigned work? If we exclude other work, do we run the risk of improving productivity in one area at the cost of others?

These questions are being asked at the right time—compared with if we started with the data. If we started with a vague idea (instead of a root question) and jumped to the data—we’d be asking these questions after collecting reams of data, perhaps analyzing them and creating charts and graphs. Only when we showed the fruits of our labor to the client would we find out if we were on the right track.

I want to help you avoid wasting your time and resources. I want to convince you to build your metrics from a position of knowledge.

Collecting Measures and Data

Now that we’ve identified the information needed (and measures that make up that information) we need to collect the data. This is a lot easier with the question, metric picture (answer), and information already designed. The trick here is not to leave out details.

It’s easy to skip over things or leave parts out because we assume it’s obvious. Building on the workload example, let’s look at some of the data we’d identify.

First we’ll need task breakdowns so we know what the “work” entails. What comprises the tasks—so we can measure what tasks each worker “can” do. With this breakdown, we also need classifications for the types of tasks/work. When trying to explain concepts, I find it helpful to use concrete examples. The more abstract the concept, the more concrete the example should be.

- Task 1: Provide second-level support

- Task 1a: Analyze issue for cause

- Task 1b: Determine solution set

- Task 1c: Select best solution

This example would be categorized as “support.” Other categories of a task may include innovation, process improvement, project development, or maintenance.

We’ll also need a measure of how long it takes each worker to perform each task, as seen in Table 3-1.

Table 3-1. Amount of Time Workers Perform Tasks

|

Worker |

Task 1 |

Task 2 |

|---|---|---|

|

A |

1 hr average |

15 minutes average |

|

B |

1.5 hrs average |

30 minutes average |

|

C |

1.6 hrs average |

28 minutes average |

If we have measures for the work components, we should be able to roll this data “up” to determine how long it takes to do larger units of work.

Next, we’ll need measures of what is assigned currently to each worker.

Worker A is working on support while workers B and C are working on maintenance.

Since we need to know what each worker is capable of (“can do”) we will need to know the skill set of each worker. With specific identification of what they “can’t” do. Many times we find the measure of X can be determined in part (or fully) by the measure of the inverse value1/x.

Worker A is not capable of doing maintenance work. That’s why he isn’t assigned to maintenance and does the support-level work instead.

Again, it’s a lot easier once we work from the top down. Depending on the answers we would perform investigations to ensure the assumptions we come to are correct. Then we can make changes (improvements) based on these results.

Worker A wants to do more maintenance-type tasks, but doesn’t feel confident in her abilities to do so. The manager chose to develop a comprehensive training program for Worker A.

Workers B and C showed they had the skills necessary to provide support, and were willing to do so. The manager divided the support work more evenly between the team.

These types of adjustments (and new solutions) could be made throughout, depending on the answers derived from the metrics.

It was not necessary to be “perfect” in the identification of all measures and data. If you are missing something, that should become evident when trying to build the information and, finally, the metric. If you’re missing something, it will stand out. If you have data or measures that you don’t need, this, too, will become quickly evident when you put it all together for the metric.

You’re not trying to be perfect out of the gate, but you definitely want to be as effective as possible. You’d like to be proactive and work from a strong plan. This happens when you use the root question and metric as your starting point.

It is truly amazing to see how a picture—not charts and graphs, but a creative drawing depicting the answer—works. It helps focus your efforts and keeps you from chasing data.

The metric “picture” provides focus, direction, and helps us avoid chasing data.

How to Collect Data

Once we’ve designed what the metric will look like, and have an idea of what information, measures, and data we’ll need to fill it out, we need to discuss how to gather the needed parts. I’m not going to give you definitive steps as much as provide guidelines for collecting data. These “rules of thumb” will help you gather the data in as accurate a manner as possible.

Later, we’ll expand on some of the factors that make the accuracy of the data uncertain. This is less a result of the mechanisms used and more a consequence of the amount of trust that the data providers have with you and management.

Use Automated Data When Possible

When I see a “Keep Out, No Trespassing” sign, I think of metrics. A no-trespassing sign is designed to keep people out of places that they don’t belong. Many times it’s related to safety. In the case of collecting data, you want to keep people out.

Why? The less human interaction with the data, the better. The less interaction, the more accurate the data will be, and the higher level of confidence everyone can have in its accuracy. Whenever I can collect the data through automated means, I do so. For example, to go back to the example in Chapter 2, rather than have someone count the number of ski machine or stair stepper users, I’d prefer to have some automated means of gathering this data. If each user has to log in information on the machine (weight, age, etc.) to use the programming features, the machine itself may be able to provide user data.

The biggest risk with using automated data may be the abundance and variety. If you find the exercise machines can provide the data you are looking for (because you worked from the question to the metric, down to the information and finally measures/data), great! But normally you also find a lot of other data not related to the metric. Any automated system that provides your data will invariably also provide a lot of data you aren’t looking for.

For example, you’ll have data on the demographics I already listed (age and weight). You’ll also have data on the length of time users are on the machines, as well as the exercise program(s) selected; the users’ average speed; and the total “distance” covered in the workout. The machine may also give information on average pulse rate. But, if none of this data serves the purpose of answering your root question, none of it is useful.

In our workload example, it will be difficult to gather data about the work without having human interaction. Most work accounting systems are heavily dependent on the workers capturing their effort, by task and category of work.

Beware!

So what happens when your client finds out about all of this untapped data?

He’ll want to find a use for it! It’s human nature to want to get your money’s worth. And since you are already providing a metric, the client may also want you to find a place for some of this “interesting” data in the metric you’re building. This risk is manageable and may be worth the benefit of having highly accurate data.

The risk of using automated data is that management will want to use data that has no relation to your root question, just because this extra data is available.

You should also be careful of over-trusting automated data. Sometimes the data only seems to be devoid of human intervention. What if the client wants to use the weight and age data collected in the ski machine? Well, the weight may have been taken by the machine and be devoid of human interaction (besides humans standing on the machine), but age is human-provided data, since the user of the machine has to input this data.

Collecting data using software or hardware are the most common forms of automated data collection. I don’t necessarily mean software or hardware developed for the purpose of collecting data (like a vehicle traffic counter). I mean something more like the ski-machine, equipment designed to provide a service with the added benefit of providing data on the system. Data collected automatically provides a higher level of accuracy, but runs the risk of offering too much data to choose from. Much of the data I use on a daily basis comes from software and hardware—including data on usage and speed.

Surveys are probably the most common data-gathering tool. They are used in research (Gallup Polls), predictive analysis (exit polls during elections), feedback gathering (customer satisfaction surveys), marketing analysis (like the surveyors walking in shopping malls, asking for a few minutes of your time) and demographic data gathering (the US census). Surveys are used whenever you want to gather a lot of data from a lot of people—people being a key component. Surveys, by nature, involve people.

The best use of surveys is when you are seeking the opinions of the respondents. Any time you collect data by “asking” someone for information, the answer will lack objectivity. In contrast to using automated tools for collecting (high/total objectivity), surveys by nature are highly/totally subjective. So, the best use of the survey is when you purposefully want subjectivity.

Customer satisfaction surveys are a good example of this. Another is marketing analysis. If you want to know if someone likes one type of drink over another, a great way to find out is to ask. Surveys, in one way or another, collect your opinion. I lump all such data gathering under surveys—even if you don’t use a “survey tool” to gather them. So, focus groups, and interviews fit under surveys. We’ll cover the theories behind the types of surveys and survey methods later.

Use People

So far I’ve recommended avoiding human provision of data when accuracy is essential. I’ve also said that when you want an opinion, you want (have) to use humans. But, how about when you decide to use people for gathering data other than opinions? What happens when you use people because you can’t afford an automated solution or an automated solution doesn’t exist?

I try to stay fit and get to the gym on a regular basis. I’ve noticed that a gym staff member often walks around the facility with a log sheet on a clipboard. He’ll visually count the number of people on the basketball courts. He’ll then take a count of those using the aerobic machines. Next, the free weights, the weight machines, and finally the elevated track. He’ll also check the locker room, and a female coworker will check the women’s locker room.

How much human error gets injected into this process? Besides simply miscounting, it is easy to imagine how the counter can miss or double-count people. During his transition between rooms, areas, and floors of the facility, the staff member is likely to miss patrons and/or count someone more than once (for example, Gym-User A is counted while on the basketball court, and by the time the staffer gets to the locker room, Gym-User A is in the locker room, where he is counted again). Yet, it’s not economically feasible to utilize automated equipment to count the facility’s usage by area.

We readily accept the inherent inaccuracy in the human-gathered form of data collection. Thus we must ask the following:

- How critical is it to have a high degree of accuracy in our data?

- Is high accuracy worth the high cost?

- How important is it to have the data at all? If it’s acceptable to simply have some insight into usage of the areas, a rough estimate may be more than enough

Many times you collect data using humans because we need human interaction to deal with the situation that generates the data. A good example is the IT help desk. Since you choose to have a human answer the trouble call (vs. an automated system), much of the data collected (and later used to analyze trends and predict problem areas) is done by the person answering the phone. Even an “automated” survey tool (e-mails generated and sent to callers) is dependent on the technician correctly capturing each phone caller’s information.

Documenting Your Metrics

Now that you’ve designed your metric, you need to document it. Not only what you’ll measure, but how.

In Why Organizations Struggle So Hard to Improve So Little, my coauthors and I addressed the need for structure and rigor in documenting work with metrics. More than any other organizational development effort, metrics require meticulous care. Excellent attention to detail is needed—not only in the information you use within the metric (remember the risks of human involvement), but also with the process involved.

In this chapter, we’ll cover identifying the many possible components of a metric development plan and documenting the metric development plan so that it becomes a tool for not only the creation of the metric, but a tool for using it effectively.

The Components of a Well-Documented Metric

Besides documenting the components of the metric—data, measures, information, pictures, and of course, the root question we will also need to capture how these components are collected, analyzed, and reported. This will include timetables, information on who owns the data, and how the information will be stored and shared. You may also include when the metric will no longer be necessary.

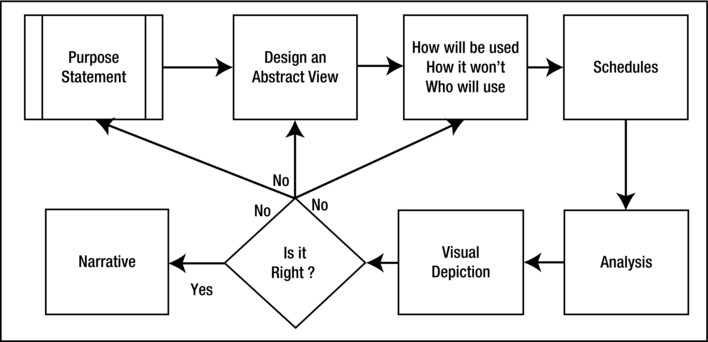

By fully documenting the metric, it will make it well-defined, useful, and manageable. At a minimum, it should include the following:

- A purpose statement

- An explanation of how it will be used

- An explanation of how it won’t be used

- A list of the customers of the metrics

- Schedules

- Analysis

- Visuals or “a picture for the rest of us”

- A narrative

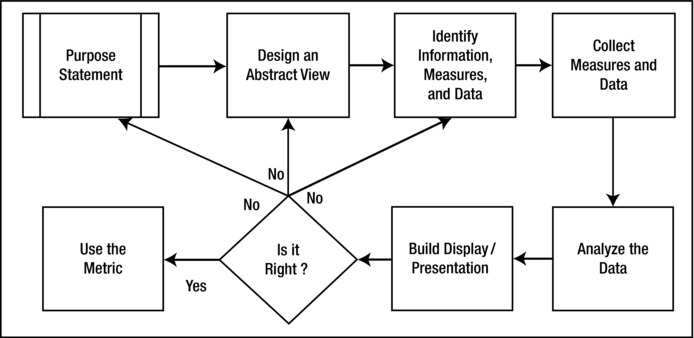

Is the purpose statement the same as your root question? The answer is, “maybe.” You will document the purpose statement when you identify the root question as shown in Figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2. Purpose Statement

If you have a well-formed root question and you have dug as deep as you can, your root question may very well contain the purpose statement. Consider the following example:

Root Question: “How well are we providing customer support using online chat?”

Purpose Statement: “To ensure that we are providing world-class customer support using online chat.”

Not much of a distinction between the two. It does provide a clearer requirement. It gives the underlying reasons for the question, and therefore the metric. The purpose of the metric is usually larger than providing insights or an answer to your root question. There is usually a central purpose to the question being asked. This purpose allows you to pull more than one metric together under an overarching requirement.

This underlying purpose will give us a much clearer guide for the metric. It will also allow us to identify other metrics needed, if you are ready to do so. You may have to settle for working with the question you currently have and get to the bigger-picture needs in the future. But it’s always best to have the big picture—it allows you to keep the end in mind while working on parts of the picture.

Your root question is the foundation of the metric and the purpose statement. If you’ve identified a good root question, the question and your purpose may be one and the same.

When documenting the metric, I make a point to capture both the root question and the purpose. If they are synonymous, no harm is done. If they are not, then I gain more insight into what the metric is really all about.

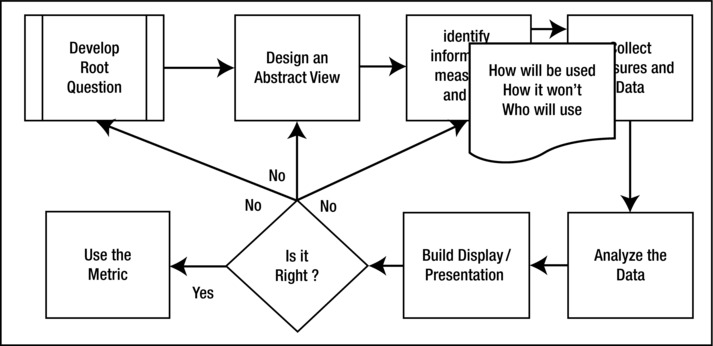

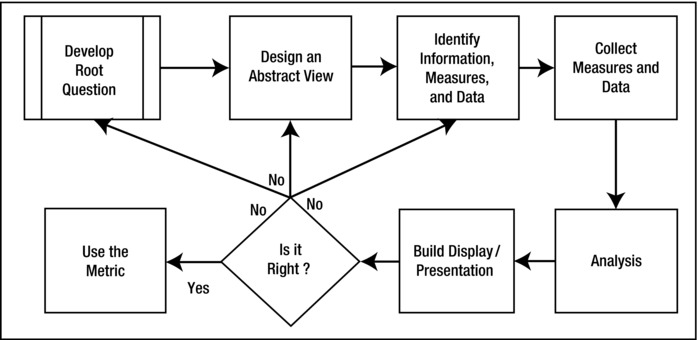

Figure 3-3 shows the three major things to capture during the collection of data, measures and information.

Figure 3-3. The “How” and “Who”

How Information Will Be Used

Along with the root question and purpose, you should articulate clearly how the metric will be used. This provides a key tool in helping overcome the fear people have of providing data. It will also help with the fear, uncertainty, and doubt people have toward the way the data will be used. Again, if you have a well-formed, clear, and foundational root question and purpose statement, this should be easy. While it may be easy to define how the metric will be used, that doesn’t make the definition obvious. You need to ask the question directly: “How will you use the metric?” Your goal is to try and get the most direct answer. The more direct the question, the higher likelihood that you’ll get a direct answer.

- Vague answer: “To improve our processes.”

- Direct answer: “To measure how the changes we implemented affect the process.”

- More specific answer: “To measure how the changes we implemented affect the process and allow for course corrections.”

If public speaking is one of the greatest fears, the use of personal data might be a close second. Not just any numbers and values—but data that can be used to hurt an individual or create negative public perception of our organization. We imagine the worst, it’s in our nature. So when we are asked to provide data, especially data that we believe reflects in any way upon ourselves or our departments, tremendous fear is created.

When we don’t know the reason, we imagine the worst possible scenarios. It’s our nature.

When the data you are collecting (and later analyzing and reporting on) can be indicators about an individual, the fear factor becomes exponentially greater. It doesn’t even matter if you plan to use the data at an aggregate level, never looking at the individual. If the data could be used at the individual level, the fear is warranted.

Time to Resolve can be a good effectiveness measure, used to improve overall customer service. The purpose may be simply to achieve better customer service and, therefore, satisfaction. But if you fail to communicate this purpose, the root question, and how you will use the answers—the individuals providing the data will imagine the worst.

Be forewarned. Even if you have an automated system to collect the data (for example, the day and time the incident was opened and closed), the ones opening and closing the case in that system are still providing the data.

If the staff learns that you are gathering data on resolution speeds, they will “hear” that you are collecting data on how long it takes them to resolve the case. Not how long it takes the team or the organization to resolve most cases, but instead how long it takes each of them individually to do the work. And, if you are collecting data on an individual’s performance, the individual in question will imagine all of the worst possible scenarios for how you will use that data.

So your innocent and proper Time to Resolve measure, if unexplained, could create morale problems due to fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

If fear is born of ignorance, then asking for data without sharing the purpose makes you the midwife.

We need to combat this common problem. To create a useful metric, you have to know, in advance of collecting the data, how the results (answers) will be used. It is essential for designing the metric properly and identifying the correct information, measures, and data. It is also essential if you want accurate data wherever human-provisioning is involved.

The explanation of how the metric and its components will be used should be documented. Don’t get hung up on the need to make it pretty. Another key to getting better answers (or one at all if the respondent is still reluctant), is to communicate how the results won’t be used.

Explain How Information Won’t Be Used

If you want accurate data, you have to be able to assure the people involved in providing the data how you will and how you won’t use the data. And how you won’t use it may be more important to the person providing the data to you than how you will use it.

The most common and simple agreement I make is to not provide data to others without the source’s permission. If you provide the data, it’s your data. You should get to decide who sees it.

Defining how the metrics won’t be used helps prevent fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

Identify Who Will Want to Use the Metrics

While you may believe you are the only customer who wants to view or use the metric, chances are there are many customers of your metrics. A simple test is to list all of the people you plan on sharing your information with. This list will probably include your boss, your workers, and those who use your service.

Anyone who will use your metric is a customer of it. You should only show it to customers.

Everyone that you plan to share your metrics with becomes a customer of that metric. If they are not customers, then there is no reason to share the information with them. You may be a proponent of openness and want to post your metrics on a public web site, but the information doesn’t belong to you. It is the property of those providing the data. It is not public information; it was designed to help the organization answer a root question. Why share it with the world? And today we know that if you share it publicly, it’s in the public domain forever.

The provider of the data should be the primary metric customer.

The possible customers are as follows:

- Those who provide the data that goes into creating the metric.

- Those who you choose to share your metrics with.

- Those who ask you for the metric and can clearly explain how they will use the metric.

It is important to clearly identify the customers of your metrics because they will have a say in how you present the metric, its validity, and how it will be used. If you are to keep to the promise of how it will and won’t be used, you have to know who will use it and who won’t.

Who will and won’t use the metric is as important as how it will and won’t be used.

Schedule for Reporting, Analyzing, and Collecting

The gathering of the data, measures, and information you will use to build the metric requires a simple plan. Figure 3-4 shows the timing for developing this part of the documentation.

Figure 3-4. Schedules

Most metrics are time-based. You’ll be looking at annual, monthly, or weekly reports of most metrics. Some are event-driven and require that you report them periodically. You will have to schedule at least three of the following facets of your metric:

- Schedule for reporting. Look at the schedule from the end backward to the beginning. Start with what you need. Take into account the customers that you’ve identified to help determine when you will need the metrics. Based on how the metrics will be used will also determine when you’ll need to report it.

- Schedule for analysis. Based on the need, you can work backward to determine when you’ll need to analyze the information to finalize the metric. This is the simplest part of the scheduling trifecta, since it is purely dependent upon how long it will take you to get the job done. Of course, the other variable is the amount of data and the complexity of the analysis. But, ultimately, you’ll schedule the analysis far enough in advance to get it done and review your results.

- Schedule for collection. When will you collect the data? Based on when you will have to report the data, determine when you will need to analyze it. Then, based on that, figure out when you will need to collect it. Often, the schedule for collecting the data will be dependent on how you collect it. If it’s automated, you may be able to gather it whenever you want. If it’s dependent on human input, you may have to wait for periodic updates. If your data is survey-based, you’ll have to wait until you administer the surveys and the additional time for people to complete them.

Since you started at the end, you know when you need the data and can work backwards to the date that you need to have the data in hand. Depending on the collection method you’ve chosen, you can plan out when you need to start the collection process and schedule accordingly.

If it’s worth doing right, it’s worth making sure you can do it right more than once. But remember, documenting the metric isn’t just about repeatability, it’s about getting it right the first time by forcing yourself to think it all out.

Documenting analysis happens when you think it does. . .during the analysis phase.

Figure 3-5. Analysis

After data collecting, the next thing most people think of when I mention metrics is analysis. All of the statistics classes I’ve taken lead to the same end: how to analyze the data you’ve carefully gathered. This analysis must include all metric data rules, edits, formulas, and algorithms; each should be clearly spelled out for future reference.

What may be in contention is the infallibility of the analysis tools. There are those that believe if you have accurate data (a few don’t even care if it’s accurate), you can predict, explain, or improve anything through statistical analysis. I’m not of that camp.

I have great respect for the benefits of analysis and, of course, I rely on it to determine the answers my metrics provide. For me, the design of the metric—from the root question, to the abstract picture, to the complete story—is more important than the analysis of the data. That may seem odd. If we fail to analyze properly, we will probably end up with the wrong conclusions and, thereby, the wrong answers. But, if we haven’t designed the metric properly to begin with, we’ll have no chance of the right answers—regardless of the quality of our analysis.

And if we have a good foundation (the right components), we should end up with a useful metric. If the analysis is off center, chances are we’ll notice this in the reporting and review of the metric.

Without a strong foundation, the quality of the analysis is irrelevant.

While the analysis is secondary to the foundation, it is important to capture your analysis. The analysis techniques (formulas and processes) are the second-most volatile part of the metric (the first is the graphical representation). When the metric is reported and used, I expect it to be changed. If I’ve laid a strong foundation through my design, the final product will still need to be tweaked.

A Picture for the Rest of Us

You’ve drawn a picture of your metric. This picture was an abstract representation of the answer to the root question. Another major component of a well thought-out metric is another picture—one your customers can easily decipher. This picture is normally a chart, graph, or table. Plan to include one in your documentation.

It can easily be more than one picture. If you need a dashboard made up of twelve charts, graphs, and tables—then so be it. If you’ve done a good job with the root question and abstract version of your metric, determining how you’ll graphically represent the metric should be an easy step. If you pick a stacked bar chart, and later realize it should have been trend lines—you can change it. No harm done.

This component should be fun. Let your creativity shine through. Find ways to explain visually so that you need less prose. A picture can truly tell a story of a thousand words. No matter how good it is, you’ll want to add prose to ensure the viewer gets it right, but we want that prose to be as brief as possible. We want the picture to tell the story, clearly. Don’t over-complicate the picture.

You may, in fact, have more data than necessary to tell your story. You may find yourself reluctant to leave out information, but sometimes less really is more. Especially if the extra information could confuse the audience. You’re not required to put data into your metric just because you’ve collected it.

I love it when someone asks, “Do I have to spell it out for you?” My answer is frequently, “Thanks! That would be nice.”

Why not? No matter how good your graphical representation is, you can’t afford to risk a misunderstanding. You rooted out the question and you designed the metric so that you could provide the right answer to the right question. You cannot allow the viewer of the metric to misinterpret the story that you’ve worked so hard to tell.

The narrative is your chance to ensure the viewer sees what you see, the way you see it. They will hopefully hear what you are trying to tell them. Any part of the plan can be updated on a regular basis, but the narrative requires frequent documentation. Since the narrative explains what the metric is telling the viewer, the explanation has to change to match the story as it changes. The narration which accompanies the picture and documents what the metric means is critical to how the metric will be used.

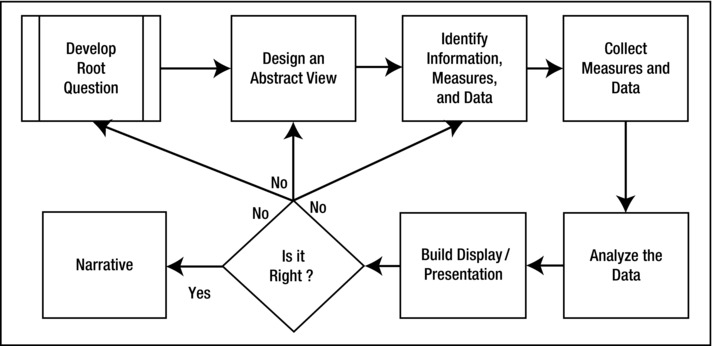

Figure 3-7 shows when the narration is documented.

Figure 3-7. Narrative

Using the Documentation

It’s valuable to put all of the details into one place. This will help you in the following three ways:

- It will help you think out the metric in a comprehensive manner.

- It will help you if you need to improve your processes.

- It will help you if you need to replicate the steps.

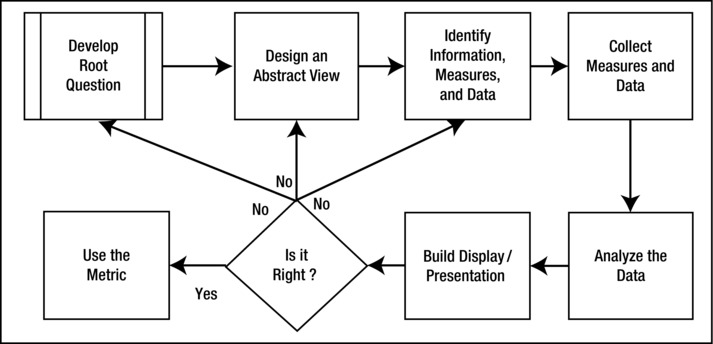

Figure 3-8 shows them all together in coordination with the process for developing the metric.

Figure 3-8. The Metric Development Process

Make the capture of your metric a living document. You will want it for reference and at times for evidence of agreements made. I find it extremely useful when the metrics are reported infrequently. The more infrequently the metrics are reported, the more likely I’ll forget the steps I followed. The collection can be very complicated, cleaning the data can be complex, and the analysis can require even more detailed steps. The more complex and the more infrequent the process, the more likely I’ll need the documentation.

Of course, even if I perform the process weekly, the responsible thing to do is to document it so others can carry it out in my absence. It provides a historical view as well as a “how to” guide. Without repeatability you can’t improve.

Without repeatability, you can’t improve.

When you document the components, don’t be afraid to be verbose. This isn’t a time for brevity. We need to build confidence in the metric and the components. We need to document as much information around each component as necessary to build trust in the following. To build that trust you have to pay special attention to:

- Accuracy of the raw data. You will be challenged on this, and rightfully so. People have their own expectations of what the answer to your root question should be. They will also have expectations regarding what the data should say about that question. Regardless of the answer, someone will think you have it wrong and check your data. Thus, you have to be accurate when you share the data. This requires that you perform quality checks of the data. It doesn’t matter if the errors are due to your sources, your formulas, or a software glitch. If your data is proven to be wrong, your metrics won’t be trusted or used.

Most examples of inaccurate raw data can be found as a result of human error but even automated tools are prone to errors, particularly in the interpretation of the data. When you’re starting, there is nothing more important than accuracy of your raw data and the biggest risk to this accuracy comes when a human touches your data.

- Accuracy of your analysis. Anyone looking over your work should be able to replicate your work by hand (using pen, paper, and a calculator). This documentation is tedious but necessary. Your process must be repeatable. Your process must produce zero defects in the data, analysis, and results.

Without repeatability you don’t really have a process.

How should you mitigate the inevitable mistakes you will undoubtedly make? Save early, save often, and save your work in more than one place. It won’t hurt to have a hard copy of your work as a final safeguard. Along with backing up your data, it’s important to have the processes documented.

You will make mistakes—it’s inevitable. The key is to mitigate this reality as much as possible.

Another tool for mitigating mistakes is to use variables in all of your formulas. If you’re using software to perform equations, avoid any raw data in the formulas. Put any values that you will reuse in a separate location (worksheet, table, or file). Not only does it allow you to avoid mistakes, it makes modifying the formulas easier.

Reference all values and keep raw data out of the equation.

Recap

I have introduced a taxonomy so that we can communicate clearly around the subject of metrics. In this chapter, I covered the theory and concept of designing a metric and the high-level process for collecting, analyzing, and reporting the data, measures, and information that go into making up that metric.

- Getting to the root question: It is imperative to get to the root question before you start even “thinking about” data. The root question will help you avoid waste. To get to the real root, I discussed using Five Whys, facilitating group interventions, and being willing to accept that the answer may not include metrics. Make sure you define every facet of the question so you are perfectly clear about what you want.

- Testing the root question: I provided some suggestions on how you can test if the question you’ve settled upon is a true root question. Even with the tests, it’s important to realize that you may not have reached it when you draw your picture. You may have to do a little rework.

- Developing a metric: This is more about what you shouldn’t do than what you should. You shouldn’t think about data. You shouldn’t design charts and graphs. You shouldn’t jump to what measures you want. Stay abstract.

- Being an artist: The best way I’ve found to stay abstract is to be creative. The best way to be creative is to avoid the details and focus on the big picture. One helps feed the other. Draw a picture—it doesn’t have to be a work of art.

- Identifying the information, measures, and data needed: Once you have a clear picture (literally and figuratively) it’s time to think about information, measures and data. Think of it like a paint-by-numbers picture. What information is required to fill the picture in? What color paints will you need? And make sure you don’t leave out any essential components.

- Collecting measures and data: Now that you know what you need, how do you collect it?

- How to collect data: I presented four major methods for collecting data: Using automated sources, employing software and hardware, conducting surveys, and using people.

I also covered the basics of how and where to document your work. The metric is made up of the following components you need to document:

- A purpose statement

- An explanation of how it will be used

- An explanation of how it won’t be used

- A list of the customers of the metrics

- Schedules

- Analysis

- Visuals or “a picture for the rest of us”

- A narrative

Accuracy is critical. I stressed the importance of accuracy in your data (source dependent), your collection (process dependent) and your analysis (process and tool dependent). I also offered the benefits of making your processes repeatable.