Chapter 1

Welcome to Android Gaming

I began developing on Android in early 2008 on the beta platform. At the time, no phones were announced for the new operating system and we developers genuinely felt as though we were at the beginning of something exciting. Android captured all of the energy and excitement of the early days of open source development. Developing for the platform was very reminiscent of sitting around an empty student lounge at 2:00 a.m. with a Jolt cola waiting for VAX time to run our latest code. It was an exciting platform to see materialize, and I am glad I was there to see it.

As Android began to grow and Google released more updates to solidify the final architecture, one thing became apparent: Android, being based on Java and including many well known Java packages, would be an easy transition for the casual game developer. Most of the knowledge that a Java developer already had could be recycled on this new platform. The very large base of Java game developers could use that knowledge to move fairly smoothly onto the Android platform.

So how does a Java developer begin developing games on Android and what tools are required? This chapter aims to answer these questions and more. Here, you will learn how to block out your game’s story into chunks that can be fully realized as parts of your game. We’ll explore some of the essential tools required to carry out the tasks in future chapters

This chapter is very important, because it gives you something that not many other gaming books have—a true focus on the genesis of a game. While knowing how to write the code that will bring a game to life is very important, great code will not help if you do not have a game to bring to life. Knowing how to get the idea for your game out of your head in a clean and clear way will make the difference between a good game and a game that the player can’t put down.

Programming Android Games

Developing games on Android has its pros and cons, which you should be aware of before you begin. First, Android games are developed in Java, but Android is not a complete Java implementation. Many of the packages that you may have used for OpenGL and other graphic embellishments are included in the Android software development kit (SDK). “Many” does not mean “all” though, and some very helpful packages for game developers, especially 3-D game developers, are not included. Not every package that you may have relied on to build your previous games will be available to you in Android.

With each release of new Android SDK, more and more packages become available, and older ones may be deprecated. You will need to be aware of just which packages you have to work with, and we’ll cover these are we progress through the chapters.

Another pro is Android’s familiarity, and a con is its lack of power. What Android may offer in familiarity and ease of programming, it lacks in speed and power. Most video games, like those written for PCs or consoles, are developed in low-level languages such as C and even assembly languages. This gives the developers the most control over how the code is executed by the processor and the environment in which the code is run. Processors run very low-level code, and the closer you can get to the native language of the processor, the fewer interpreters you need to jump through to get your game running. Android, while it does offer some limited ability to code at a low level, interprets and threads your Java code through its own execution system. This gives the developer less control over the environment the game is run in.

This book is not going to take you though the low-level approaches to game development. Why? Because Java, especially as it is presented for general Android development, is widely known, easy to use, and can create some very fun, rewarding games.

In essence, if you are already an experienced Java developer, you will find that your skills are not lost in translation when applied to Android. If you are not already a seasoned Java developer, do not fear. Java is a great language to start learning on. For this reason, I have chosen to stick with Android’s native Java development environment to write our games.

We have discussed a couple of pros and cons to developing games on Android. However, one of the biggest pros to independent and casual game developers to create and publish games on the Android platform is the freedom that you are granted in releasing your games. While some online application stores have very stringent rules for what can be sold in them and for how much, the Android Market does not. Anyone is free to list and sell just about anything they want. This allows for a much greater amount of creative freedom for developers.

In Chapter 2, you’ll create your first Android-based game, albeit a very simple one. First, however, it’s important look behind the scenes to see what inspires any worthwhile game, the story.

Starting with a Good Story

Every game, from the simplest arcade game to the most complex role-playing game (RPG), starts with a story. The story does not have to be anything more than a sentence, like this: Imagine if we had a giant spaceship that shot things.

However, the story can be as long as a book and describe every land, person, and animal in the environment of a game. It could even describe every weapon, challenge, and achievement.

NOTE: The story outlines the action, purpose, and flow of a game. The more detail that you can put into it, the easier your job developing the code will be.

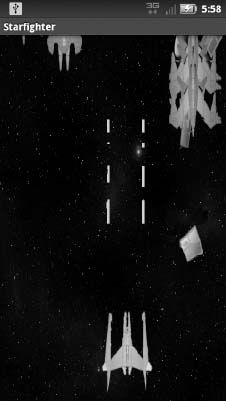

Take a look at the game in Figure 1–1, what does it tell you? This is a screen shot from Star Fighter; the game that you will be developing through the beginning chapters of this book. There is a story behind this game as well.

Figure 1–1. Star Fighter screen shot

Most of us never get to read the stories that helped create some of our favorite games, because the stories are really only important to the people who are creating the game. And assuming the developers and creators do their jobs well, the gamer will absorb the story playing the game.

In small, independent development shops, the stories might never be read by anyone other than the lead developer. In larger game-development companies, the story could be passed around and worked on by a number of designers, writers, and engineers before it ends up in the hands of the lead developers.

Everyone has a different way to write and handle the creation of the story for the games that they want to make. There is no right or wrong way to handle a game’s story other than to say that it needs to exist before you begin to write any code. The next section will explain why the story is so important.

Why Story Matters

Admittedly, in the early days of video gaming, stories may not have been looked upon as importantly as they are now. It was much easier to market a game that offered quick enjoyment without needing to get very deep into its purpose.

This is definitely not the case anymore. People, whether they are playing Angry Birds or World of Warcraft, expect a defined purpose to the action. This expectation may even be on a subconscious level, but your game needs to hook the players so that they want to keep playing. This hook is the driving purpose of the story.

The story behind your game is important for a few different reasons. Let’s take a look at exactly why you should spend the time to develop your story before you begin to write any code for your game.

The first reason why the story behind your game is important is because it gives you a chance to fully realize your game, from beginning to end, before you begin coding. No matter what you do for a living, whether you are a full-time game developer or are just doing this as a hobby, your time is worth something.

In the case of a full-time game developer, there will be an absolute dollar value assigned to each hour you spend coding and create a game. If you are creating independent games in your spare time, your time can be measured in the things you could be doing otherwise: fishing, spending time with others, and so on. No matter how you look at it, your time has a definite and concrete worth, and the more time you spend coding your game, the more it costs.

If your game is not fully realized before you begin working on your code, you will inevitably run into problems that can force you to go back to tweak or completely rewrite code that was already finished. This will cost you in time, money, or sanity.

NOTE: To be fully realized an idea must be complete. Every aspect of the idea has been though out and carefully considered.

As a game developer, the last thing that you want is to be forced to go back and change code that is finished and possibly even tested. Ideally, your code should be extensible enough that you can manipulate it without much effort—especially if you want to add levels or bosses onto your game later. However, you may have to recode something relatively minor, like the name of a character or environment, or you might have to change something more drastic. For example, maybe you realized you never gave your main character the weapon needed to finish the game because you didn’t know how it was going to end when you started building it.

Having a fully developed story arc for your game will give you a linear map to follow when writing your code. Mapping out your game and its details like this will save you from many of the problems that could cause you to recode already-finished parts of your game. This leads us to the next reason why you should have a story before you begin coding.

The story that your game is based on will also serve as reference material as you write your code. Whether you need to look back on the correct spelling of the name of a character name or group of villains or to refresh your memory as to the layout of a city street, you should be able to pull your information from your.

Being able to refer to the story for details is especially key if multiple people are going to be working on the game together. There may be sections of the story that you did not write. If you are coding something that refers to one of those sections, the fully realized story document is an invaluable piece of reference material for you.

Having a story developed to this scale and magnitude means that multiple people can refer to the same source and they will all get the same picture of what needs to be done. If you have multiple people working together in a collaborative environment, it is critical that every person be moving in the same direction. If everyone starts coding what they think the game should be, each person will code something different. A well-written story, one that can be referred to by every developer working on the game, will help keep the team moving toward the same goal.

But how do you get the story out of your head and prepare it to be referenced by either yourself or others? This question will be answered in the following section.

Writing Your Story

There is no trick to writing out your story. You can be as elaborate or rudimentary as you feel is necessary. Anything from a few quick sentences on the scratch pad near your PC to a few pages in a well-formatted Microsoft Word document will suffice. The point is not to try to publish the story as a book; rather, you just need to get the story out of your head and into a legible format that can be referenced and hopefully not changed.

The longer the story stays in your head, the more time you will have to change the details. When you change any details at all in the story, you risk having to rewrite code (and we have already discussed the dangers of this). Therefore, even if you are a one-person, casual-development machine, and you think that it is not necessary to write down a story just for you, think again. Writing down the story ensures that you will not forget or accidentally change any of the details.

No doubt you have a game in mind that you want to develop as soon as you learn the skills in this book. However, you may not have ever really considered what the story for that game would be. Give some thought to that story.

TIP: Take some time now to write down a quick draft of your game, if you have one in mind. When you finish, compare it to the mock story that follows.

Let’s look at a quick example of a story that can be used to develop a game.

John Black steals a somewhat-fast but strong car from a local impound. The bad guys catch up to him quickly. Now, he has to make it out of Villiansburg with the money, avoid the police, and fight off the gang he stole the money from. The gang’s cars are faster, but luckily for John, he can shoot and drive at the same time. Hopefully, the lights are still on at the safe house.

In that quick story, even though there are few details, you still have enough for one casual developer to start working on fairly simple game. What can you get out of this paragraph?

The first concept that comes to mind from this short story would be a top-down, arcade-style driving game; think original Spy Hunter. The driver, or the car, could have a gun to fire at enemy vehicles. The game could end when the player reaches the edge of the town, or possibly a safe house or garage of some sort.

This short story even has enough details to make the game a bit more enjoyable to play. The main character has a name, John Black. There are two sets of enemies to avoid: the police and the gang. The environment is made up of the streets of Villiansburg, and the majority of the enemy vehicles travel faster than the main character’s. There is definitely enough good material here to make a quick, casual game.

Already the metaphoric wheels in your brain should be turning out ideas for this game. A fair amount of good, arcade-style action is described in this one short paragraph. If you can describe the game that you want to make in a short paragraph like this, than as a single, casual developer, you are well on your way to making a fairly enjoyable game.

Where one short paragraph might have enough detail for a fairly convincing casual game, imagine what a longer story could provide. The more detail that you can put into your story now, the easier your job will be as you are coding, and the better your game will be.

Take some extra time with your story to get the details just right. Sure a short paragraph, like the one in this section, is enough to go on, but more details could definitely help you as you are coding. Here is a list of questions that you should already be asking yourself after reading this story:

- What kind of car does John steal and drive?

- Why did he steal the money?

- What kind of weapon does he have?

- What kind of weapons, if any, are on the car?

- Is Villiansburg a city or country environment?

- Is there a boss battle at the end?

- How is scoring accumulated, if at all?

If we go back and answer some of these questions, the story may look like this.

John Black, framed for a crime he didn’t commit, seizes an opportunity to get back at the gang that set him up. He intercepts $8 million that was on its way to Big Boss, the leader of the Bad Boys. He knows he can’t get away on foot, so he steals a somewhat-fast but strong black sedan from a local impound.

This car has everything: twin mounted machine guns, oil slick, and mini missiles.

The bad guys catch up to him quickly. Now, he has to make it out of the crowded city streets of Villiansburg with the money. Dilapidated and boarded up buildings line the streets. The faster John can drive, the better his chances are of making it out alive. All he has to do is avoid the police and fight off the gang he stole the money from.

The gang’s cars might be faster, but luckily for John, he can shoot and drive at the same time. He will need these skills when Big Boss catches up to him at the edge of town in his re-commissioned U.S. Army tank.

If John can defeat Big Boss, he will keep the money, but if he gets hit along the way, Big Boss’s henchmen will take what they can get away with until John has nothing. John better be careful, because Big Boss’s henchmen will be coming at him with everything they have: sports cars, motorcycles, machine guns, and even helicopters.

Hopefully, the lights are still on at the safe house.

Now, let’s take a look at the story again. We have a lot more to go on now, and clearly, the more detailed story would make for more interesting game play. Anyone coding this game would now be able to discern the following game play details.

- The main character’s car is a black sedan.

- The car has two machine guns, missiles, and oil slicks as weapons.

- The environment is a crowded city street lined with rundown, boarded up buildings.

- The player will start with $8,000,000 (8,000,000 points).

- The player will lose money (points) if an enemy catches or hits him.

- The enemy vehicles will be sports cars, motorcycles, and helicopters.

- At the end of the city is a boss battle against a tank.

- The game ends when the play is out of money (points).

As you can see, the picture of what needs to be done is much clearer. There would be no confusion over this game play. This is why it is important to put as much detail as possible into the story that your game will be based on. You will definitely benefit from all of the time you put in before you begin coding.

Now that we’ve addressed some of the reasons why you might want to develop games on the Android platform and reviewed the philosophy behind making your game matter, let’s look at the approach I’ll be taking and what tools you will need to be a successful Android game developer. These will serve as the basis for all projects in the remaining chapters.

The Road You’ll Travel

In this book, you will learn both 2-D and 3-D development. If you start from the beginning of this book and work through the basic examples, building the sample 2-D game as you go, the chapters on 3D graphics should be easier to pick up. Conversely, if you try to jump straight to the chapters on 3-D development, and you are not a seasoned OpenGL developer, you may have a harder time understanding what is going on.

As with any lesson, class, or path of learning, you will be best served by following this book from the beginning to the end. However, if you find that some of the earlier examples are too basic for your experience level, feel free to move between chapters.

Gathering Your Android Development Tools

At this point, you are probably eager to dive right into developing your Android game. So what tools do you need to begin your journey?

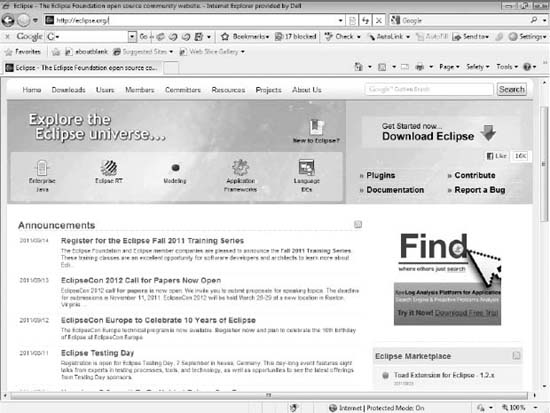

First, you will need a good, full-featured integrated development environment (IDE). I write all of my Android code in Eclipse Indigo (which is a free download). All of the examples from this book will be presented using Eclipse. While you can use almost any Java IDE or text editor to write Android code, I prefer Eclipse because of the well-crafted plug-ins, which tightly integrate many of the more tedious manual operations of compiling and debugging Android code.

If you do not already have Eclipse and want to give it a try, it is a free download from the Eclipse.org site (http://eclipse.org), shown in Figure 1–2:

This book will not dive into the download or setup of Eclipse. There are many resources, including those on Eclipse’s own site and the Android Developer’s Forum, that can help you set up your environment should you require assistance.

TIP: If you have never installed Eclipse, or a similar IDE, follow the installation directions carefully. The last thing you want is an incorrectly installed IDE impeding your ability to write great games.

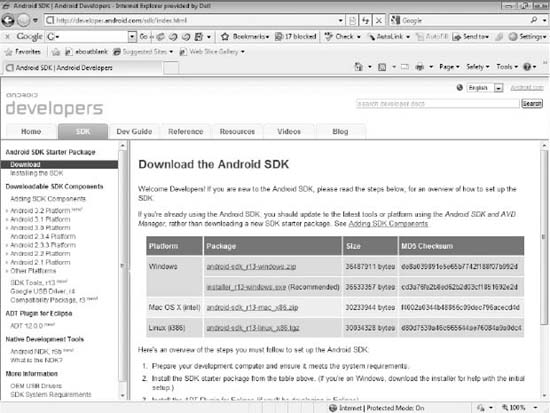

You will also need the latest Android SDK. As with all of the Android SDKs, the latest can be found at the Android developer site (http://developer.android.com/sdk/index.html), as shown in Figure 1–3:

Figure 1–3. The Android developer site

As with the IDE, many resources are available to help you download and install the SDK (and the corresponding Java components that you may need) if you need help doing so.

Finally, you should possess at least a basic understanding of development, specifically in Java. While I do my best to explain many of the concepts and practices used in creating the code for this book, I will not be able to explain the more basic development concepts. In short, my explanations alone should be enough to get you through the code in this book if you are a novice, but a more advanced Java developer will be able to easily take my examples and expand on them.

Installing OpenGL ES

Arguably one of the most important items you’ll be using is OpenGL ES, a graphics library that was developed by Silicon Graphics in 1992 for use in computer-aided design (CAD). It has since been managed by the Khronos Group and can be found on most platforms. It is very powerful and an invaluable tool to anyone who wants to create games.

NOTE: It does bear mention that the version of OpenGL that is provided with, and supported by, Android is actually OpenGL ES (OpenGL for Embedded Systems). OpenGL ES is not as fully featured as standard OpenGL. However, it is still an outstanding tool for developing on Android. Throughout this book, for ease of discussion, I will refer to the OpenGL ES functions and libraries as OpenGL; just be warned that we are actually using OpenGL ES

When most people think of OpenGL, the first things that come to mind are 3-D graphics. It’s true that OpenGL is very good at rendering 3-D graphics and can be used to create some convincing 3-D games. However OpenGL is also very good at rendering 2-D graphics. In fact, OpenGL can render and manipulate 2-D graphics much faster than the native Android calls. The native Android calls are good enough for most application developers, but for games, which require as much optimization as possible, OpenGL is the best way to go.

For those of you who may not have the most OpenGL experience, fear not. In the chapters that deal with heavy OpenGL graphics rendering, I will do my best to fully explain every call you need to make. Therefore, if the following OpenGL code looks like a foreign language to you, don’t worry; it will make sense by the end of this book:

gl.glViewport(0, 0, width, height);

gl.glMatrixMode(GL10.GL_PROJECTION);

gl.glLoadIdentity();

GLU.gluOrtho2D(gl, 0.0f, 0.0f, (float)width,(float)height);

OpenGL is a perfect tool for you to use and learn in this book, because it is a cross-platform development library. That is, you can use OpenGL and the OpenGL knowledge that you learn here across many environments and disciplines. From the iPad and iPhone to Microsoft Windows and Linux, many of the same OpenGL calls can be used across all of these systems.

Using OpenGL for your 2-D game graphics throughout this book has an added benefit.

OpenGL, for all intents and purposes, does not care if you are working with 2-D or 3-D graphics. Many of the same calls are used for both. The only difference is in how OpenGL will render the polygons when it comes time to draw to the screen. This being said, your transition from 2-D to 3-D graphics will be a lot smoother and a lot easier using OpenGL. Keep in mind that this book is not intended to be a complete desk reference on OpenGL ES, nor is it going to show you complex matrix math and other optimization tricks that you would otherwise be using in a profession game house. The truth is, as a casual game developer, the OpenGL methods provided for things like matrix math, while they come with some overhead, are good enough for learning the lessons this book.

In this book, you are going to use OpenGL ES 1.0. There are three versions of OpenGL available to Android users: OpenGL ES 1.0, 1.1, and 2.0. Why use version 1.0? First, there is already a lot of reference material available on the Internet about OpenGL ES 1.0. Therefore if you get stuck, or want to expand your knowledge, you will have a lot of places to turn for help. Second, it is tried and tested. Being the oldest of the OpenGL ES platforms, it will be available to the most devices and will have been extensively tested. Finally, it is just plain easy to pick up and learn. Also, picking up 1.1 and maybe even 2.0 after you already know 1.0 will be a lot easier.

Choosing an Android Version

One of the appeals of developing for Android is that it is so widely used across many different devices, such as mobile phones, tablets, and MP3 players. The games that you develop have a chance to run one dozens of different cell phones, tables, and even e-readers. From different wireless carriers to different manufacturers, the hardware exposure that your game could get is quite varied.

Unfortunately, this ubiquity can also be a tough hurdle for you to jump through. At any given time, there could be up to 12 different versions of Android running on dozens of different pieces of hardware. The latest tablets and phones will be running version 2.3.3, 3.0, 3.1, or 4.0—the most recent versions, which are run on the most powerful devices. Therefore, these will be the versions that we are going to target in this book.

NOTE: If you do not have an Android device to test on you can use the PC emulator. However, I highly recommend that you try to use an actual Android phone or tablet to test your code. In my testing, I have noticed some minor discrepancies when running my code in an emulator versus running it on my phone or tablet.

Most importantly, have fun as you work through the process of creating games. Games, after all, are fun, and you should have fun making them!

Summary

In this chapter, we discussed what you should expect to get out of this book. You learned the importance of story to the creation of a game and how sticking to that story can help you create better code. You also learned about the process of creating games on the Android platform, the versions of Android, and Android’s development environment. Finally, you discovered the key to creating games on the Android platform, OpenGL ES, and we covered a few pertinent details about Android version releases.