2

Making It Work

Risk management is too important to be left to chance. For risk management to work, it must be applied consistently, and this is best achieved using a structured or formal approach that requires a number of components to be in place, including:

• A supportive organization

• Competent people

• Appropriate supporting infrastructure

• A simple to use, scalable, and documented process.

These factors, which are discussed later in this chapter, are often referred to as Critical Success Factors (CSFs), for two reasons:

1. Their absence leads to a failure of risk management to deliver its full benefit to the organization.

2. Their presence increases the chances of risk management being effective and successful.

Putting Critical Success Factors in place may sound simple to achieve, but in practice making risk management work is a real challenge. This chapter explores some of the main reasons for this—not to be negative but to provide possible ways to counteract the most common reasons. Forewarned is forearmed.

A research project by The Risk Doctor Partnership in collaboration with KLCI investigated how organizations perceive the value of risk management. The survey addressed several different aspects, but two questions were particularly interesting. The first question asked “How important is risk management to project success?” with possible answers including extremely important, very important, important, somewhat important, and not important. The second question asked “How effective is risk management on your projects?” with answers ranging from extremely effective to very effective, effective, somewhat effective, or ineffective.

With 561 responses, the raw data is interesting in itself, but the correlation between answers to these two questions is fascinating. Simplifying the answers to each question into two options (positive or negative) gives four possible combinations, presented here along with the percentage of respondents who fell into each category (see Figure 2-1).

Figure 2-1: Importance and Effectiveness of Risk Management

Perhaps the combination “Not important but effective” is not really feasible because it would be unusual for risk management to be effective if the organization does not consider it to be important; indeed, less than 1 percent of people responding to the research questionnaire believed themselves to be in this situation. Indeed, if risk management is viewed as unimportant, it might not be done at all. But the other three combinations represent different levels of risk management maturity, and organizations in each of these three groups might be expected to act in very different ways.

Organizations that consider risk management to be “Important and effective” in delivering the promised benefits could become champions for risk management, demonstrating how it can work and persuading others to follow their lead. These risk-mature organizations might be prepared to supply case studies and descriptions of best practice, allowing others to learn from their good experience. Encouragingly, more than 40 percent of respondents in the research project reported being in this position. An organization that believes risk management is “Important but not effective in practice,” which is the position reported by about 41 percent of respondents (about the same as those reporting “Important and effective”), should consider launching an improvement initiative to benchmark and develop its risk management capability. Tackling the CSFs for effective risk management leads to enhanced capability and maturity, allowing the organization to reap the expected benefits.

Not surprisingly, risk management is ineffective in organizations that believe it is unimportant (“Not important and not effective”), because it is not possible to manage risk effectively without some degree of commitment and buy-in. Only 17 percent of respondents admitted to this, perhaps recognizing that it is not a particularly good place to be. These risk-immature organizations should be persuaded and educated about the benefits of risk management to the business— a task best performed by convinced insiders who can show how to apply proactive management of risk to meet the organization’s specific challenges.

It is a good idea for every organization to review its position on risk management against the two dimensions of importance and effectiveness, and to take appropriate action to move up the scale of risk management maturity. Risk management offers genuine and significant benefits to organizations, their projects, and their stakeholders, but these benefits will never be achieved without recognition of the importance of managing risk at all levels in the business, matched with operational effectiveness in executing risk management in practice.

Why Don’t We Do It?

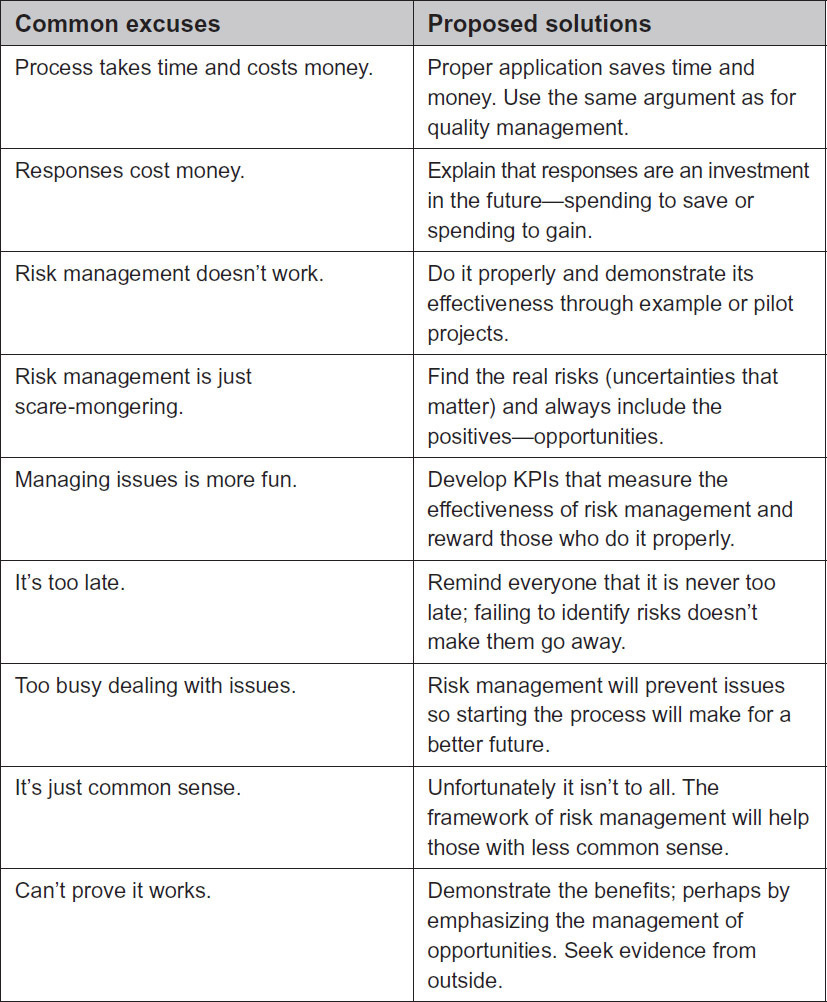

Most people would agree that risk management should be useful. If this is true, why is it not more widely used? Some of the more frequently cited reasons or excuses are listed in Figure 2-2 and described in the following paragraphs.

THE RISK PROCESS TAKES TIME AND MONEY

Risk management is not a passive activity, and there is a cost associated with executing the upfront risk process—the cost of assessing risk. Risk management requires involvement of the project sponsor, project manager, members of the project team, and other stakeholders over and above what some would consider their normal level of commitment to the project. This causes a double problem: finding time for the risk process in an already overloaded working environment is difficult; and even when time is found, the risk process costs money, as effort is spent in risk workshops and review meetings.

RISK RESPONSES COST MONEY

A central purpose of the risk process is to identify risks and determine appropriate responses, which inevitably results in the need to do new and unplanned things. This introduces a second type of cost to the risk process: the cost of addressing risk. Risk responses are in reality new project activities that were not originally considered necessary. Because risk responses were not included in the original project scope, they add to the resource requirement and budget. As a result, risk management adds to the project workload while at the same time increasing the required budget.

Figure 2-2: Excuses and Solutions

RISK MANAGEMENT DOESN’T WORK FOR US

Although risk management is not difficult, many people have unfortunately experienced it being applied ineffectively, leading them to believe that risk management doesn’t work. This situation often arises when risk management is performed without proper commitment, perhaps by organizations merely complying with a regulatory, contractual, or procedural requirement.

RISK MANAGEMENT IS JUST SCAREMONGERING

Until recently, risk management was commonly concerned only with threats. As a result, the risk process focused only on the bad things that might occur, examining every possible cause of failure and listing every potential problem. This can demotivate and create a sense of doom for the project team, which believes that the project cannot succeed given the number of identified negative risks. This can also affect senior management, project sponsors, and customers, who might believe that the project team is merely scaremongering, raising potential problems that might never happen, possibly trying to engender sympathy, or maybe even paving the way for project failure.

MANAGING ISSUES IS MORE FUN AND REWARDING

Some believe that dealing with issues, problems, or even crises is more interesting and rewarding. Individuals might gain considerable satisfaction from solving a problem, especially if it’s a big one, even if it could have been prevented by proactive risk management. In addition, many organizations reward those macho project managers who successfully resolve a major crisis and then deliver their project in line with its objectives. By contrast, the project manager who has avoided all problems by effectively applying risk management is often ignored, with the implication that “it must have been an easy project because nothing went wrong.”

IT’S TOO LATE TO CARRY OUT RISK MANAGEMENT

Some projects simply involve implementing predefined solutions in which all key objectives (time, cost, and quality) are pre-agreed and unchangeable. Where this is true, the project manager might see little point in taking time to identify risks that require additional work and more money to manage, when neither more resources nor more budget will be made available because the objectives are fixed and agreed upon in advance. The risk process might even reveal that achieving the agreed-upon project objectives is impossible—an “unacceptable” conclusion. Although many would say that part of the purpose of risk management is to expose unachievable objectives, in reality this could put the project manager in a difficult position and could result in statements like “Don’t give me problems, just give me solutions,” or “Stop complaining, just do it.”

I’M TOO BUSY DEALING WITH ISSUES

When projects are badly planned in the first place, issues and problems will quickly arise that can dominate the project’s day-to-day management. In these situations, project managers easily become consumed with the “now” problems and find it difficult, if not impossible, to worry about potential future events, even though identifying and proactively managing them would clearly be beneficial to the project. Frequently the result is that risk management never even gets started.

IT’S JUST COMMON SENSE

Everyone looks both ways when they cross the road, don’t they? Nobody would ever consider climbing a mountain without ropes, would they? The majority of people should surely carry out risk management on a day-to-day basis; it’s just common sense. If this is true, then we should expect that risk management will be applied intuitively to all projects, and that project managers will always do it without needing a formal or structured risk process.

WE CAN’T PROVE THAT RISK MANAGEMENT WORKS

Some risks that are identified never materialize, and as a result some people think that considering things that might not happen is just a waste of time. In addition, it is difficult to prove that risk management is working on a project because there is never an identical project that can be run without risk management as a control. And where the risk process only addresses threats, successful risk management means nothing happens! Since it is impossible to prove a negative, the absence of unusual problems cannot be firmly linked with the use of risk management—the project team might just have been lucky that no problems occurred.

Turning Negatives into Positives

Each of the excuses described above represents a potential barrier to implementing effective risk management. Where project stakeholders hold these views, it is important to address their concerns, correct their misperceptions, and allay their fears so that they can engage with the risk process and make it work. The following paragraphs outline possible solutions to deal with each point (summarized in Figure 2-2).

THE RISK PROCESS TAKES TIME AND MONEY

Implementing risk management does take time and does cost money. However, when applied properly, risk management actually saves time, saves money, and produces outputs of the required quality. The argument is similar to that supporting the use of quality procedures in project management, where proactive attention to potential problems ensures the best possible results by reducing wasted effort and materials caused by rework or solving problems.

RISK RESPONSES COST MONEY

The cost of implementing new activities in order to manage risks is a fundamental part of applying the risk process. Failing to respond to risks through planned response activities means that risks will go unmanaged, the risk exposure will not change, and the risk management process will not be effective. The cost of risk responses should be seen as an investment in the project’s success—“spending to save.” A similar argument exists for the cost of quality, where rework or fixing noncompliances is recognized as being more expensive than doing the job right the first time. Equally for risk management, addressing a threat pro-actively usually costs less than it does to resolve a problem when it happens. And addressing an opportunity is clearly more cost-effective than missing a potential benefit.

RISK MANAGEMENT DOESN’T WORK FOR US

Ineffective or badly applied risk management can cause more problems than it solves. Where this is the case, measures must be put in place to make the risk management process more effective, perhaps by training project team members or improving risk processes. Once these changes have been made, then the organization must ensure proper application of the changed ways of working. If the excuse that “risk management doesn’t work” is based on poor practice, the answer is to do it properly and it will work. Sometimes the belief that risk management is not applicable or helpful arises from a view that “our projects are different,” a feeling that risk management might work for others but “it doesn’t work for us.” Here, a pilot project can be particularly useful in demonstrating the benefits of doing it properly on a real project.

RISK MANAGEMENT IS JUST SCAREMONGERING

Overemphasis on identifying every potential threat to the project can be overcome in two ways. The best solution is to ensure that the risk process also pro-actively identifies and addresses upside risks (opportunities) that counteract the threats. This also helps the project stakeholders realize that the project is not all “doom and gloom,” and that things might get better as well as worse. The second part of the answer is to ensure that identified threats really do matter. Often many so-called threats may have little or no impact on the project, or might not even be risks at all. And of course, where threats are identified that really could affect the project adversely, effective responses must be developed to reduce the risk exposure. The answer to the charge that risk management is merely scaremongering is to ensure that the risk assessment is realistic and presents genuine threats and opportunities together with appropriate responses.

MANAGING ISSUES IS MORE FUN AND REWARDING

It is undoubtedly stimulating to tackle problems and crises, and it is right for organizations to reward the staff who have the skills to rescue troubled projects. However, the reward scheme should not incentivize macho behavior at the expense of prudent risk management. Organizations should also find ways to reward project managers who successfully manage the risks on their project. This may be through the creation of key performance indicators (KPIs) that mea sure the effectiveness of the risk process, linked to a risk-based bonus. One KPI related to effective risk management might be the number of issues that arise during the project: the greater the number of issues, the less effectively the risk management process has been applied.

IT’S TOO LATE TO CARRY OUT RISK MANAGEMENT

The reality is that it’s never too late, because failing to identify risks doesn’t make them go away; a risk identified is a risk that can be managed. Failing to identify and manage risks means that projects are taking risks blindfolded, leading to a greater number of problems and issues, and more missed opportunities. Even where project objectives are presented as “fixed,” this does not guarantee that they are achievable, and the aim of the risk process is to maximize the chances of achieving objectives.

I’M TOO BUSY DEALING WITH ISSUES

This excuse can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. If risk management never starts, then more issues will arise that require immediate attention, reinforcing the problem. This downward spiral must be nipped in the bud. Making risk management mandatory might solve the problem, though there is a danger that imposing a risk process will result in project teams only paying lip service to it. A better strategy is to make a convincing argument that risk management is actually good for the project, and that carrying it out will prevent further issues and make life easier.

IT’S JUST COMMON SENSE

The problem with common sense is that it’s not very common. Risk management cannot be left to intuition because the stakes are too high. Of course, some people are very good at managing risk intuitively, and these individuals might be able to trust their common sense instead of following a structured approach to risk management. However, most people require some assistance in taking the necessary steps to identify and manage risk effectively. For the majority, having a framework within which to conduct the risk process is both helpful and necessary. A structured approach to risk management helps everyone do what the best practitioners do intuitively.

WE CAN’T PROVE THAT RISK MANAGEMENT WORKS

This excuse might exist where the risk process is focused entirely on threats, since it is difficult to prove unambiguously that an absence of problems resulted from successful risk management. However, when the risk process also addresses upside risks (opportunities), a successful risk process results in measurable additional benefits, including saved time, reduced cost, and reduced rework. We recommend a broad approach to risk management covering both threats and opportunities; where this is implemented, evidence that risk management works can be gathered. It should also be recognized that risk management delivers a range of “soft” benefits in addition to those that are directly measurable, as discussed in the previous chapter. Finally, evidence can be sought either from within the organization or from other similar organizations by reviewing case studies of successful projects where the results are attributed to effective risk management.

Four Difficult Challenges

All of the excuses mentioned earlier can be addressed and overcome. Unfortunately, there are other reasons why project risk management is not undertaken where the solutions are less obvious. These are often a deep-rooted part of entrenched organizational culture. The following four challenges fall into this category. There are no simple solutions for overcoming these, but awareness of their existence can help us to manage any negative consequences.

WE HAVE RISK-PROOFED OUR PROJECTS

It is easy for us to say that all projects are risky and therefore they must include risks. Common definitions of a project emphasize that each project is unique, and uniqueness clearly implies risk. However, some project-based organizations claim to be so familiar with the projects they undertake that there can be no surprises and therefore no risks. They believe that because they are project professionals, they are immune from risk and its effects. While this may seem ridiculous, there is no denying that this perception exists. It is only when something goes seriously wrong that such an organization may recognize the need to change.

WE HAVE A “CAN-DO” CULTURE

Many organizations, and indeed many individuals as well, believe that they can cope with any situation they encounter. Anything unforeseen that occurs on their project (or in life) can just be dealt with reactively. If we have absolute confidence that we can tackle anything that arises, why should we waste time identifying risks or trying to manage them? Let’s just wait and see, and if anything happens, we’ll fix it then. This way of working can be sustainable when the surprises are minor, but it will be problematic when major, unforeseen circumstances arise.

ADMITTING TO RISKY PROJECTS WILL AFFECT OUR REPUTATION

Some organizations are unwilling to admit that their projects are risky and that they might have difficulties in delivering them on time and on budget. They fear that their reputation will be damaged if clients or the industry think they are unable to handle risk. This is specifically relevant if they think that a risky project might not get approval or might be canceled. Such a position often leads to false promises being made in respect to delivery dates and cost estimates. This might be due to “optimism bias,” unconsciously expecting a better-than-average outcome, or to “strategic misrepresentation,” a term first cited by Flyvbjerg, Holm, and Buhl in 2002—where promises are knowingly made that are unlikely to be achieved in order for the project to go ahead or continue. Flyvbjerg, Holm, and Buhl actually referred to strategic misrepresentation as lying! Such knowingly made false promises will always be found out.

WE USE AN AGILE METHODOLOGY, SO WE DON’T NEED RISK MANAGEMENT

Agile methodologies have been used for many years and have been proven to be excellent for delivering specific types of project, particularly in the IT sector, such as a new app for a mobile phone or a new e-banking product. One misconception of agile is that it does away with the need for formal project risk management. Agile itself is in many ways a response to the risks of using a waterfall life cycle. It reduces risk by adopting an iterative approach, short time frames, involvement of stakeholders, users, and so on, plus the ability to cut scope/ functionality to meet deadlines or budget restrictions. But this doesn’t mean that risk management isn’t needed at all.

There are two ways in which risk management should be used in a project using an agile approach:

1. When the project team is reviewing the product backlog to decide what functionality to include in the next iteration (sometimes called sprint or leap), one important consideration is to address high-risk elements first. But how can the project team know which elements are high-risk? This requires an assessment of the risk level of each element on a consistent basis, and then the high-risk elements can be included when the project team constructs the iteration.

2. Once the iteration is launched, it can be treated as a micro-project. There will be threats and opportunities even during the short time span of an iteration, and these need to be identified and managed. This requires a fast and simple risk process that can be performed quickly by the project team to keep the iteration on track.

For both of these, a reduced ATOM process can be used, as described in Chapter 13.

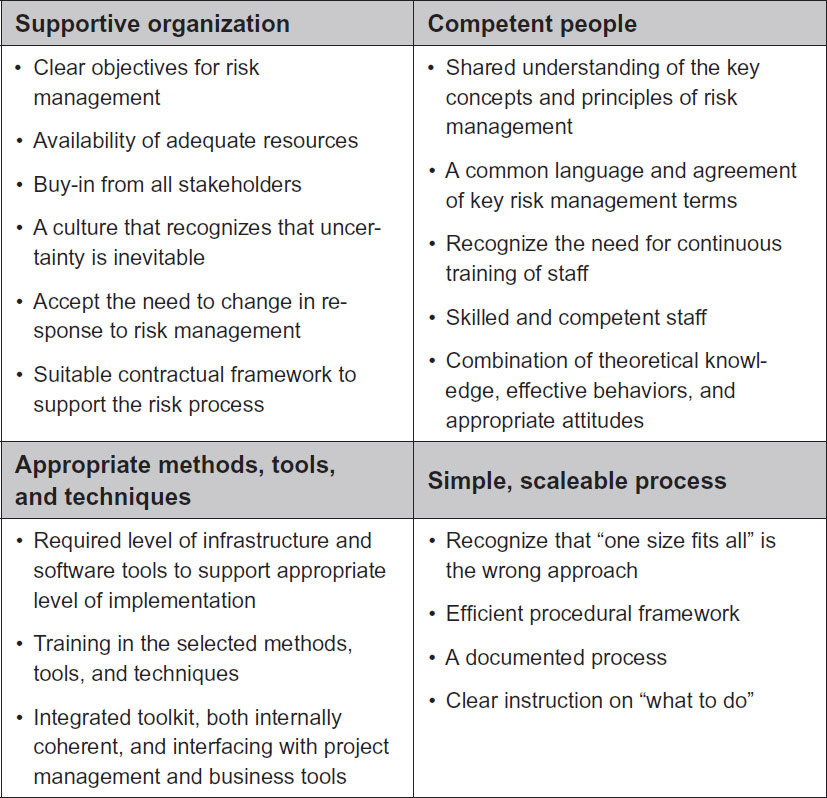

The Critical Success Factors for Risk Management

All of the common reasons/excuses/challenges for not applying risk management can be overcome by focusing on CSFs. It is possible to generate a long list of CSFs (for example, Figure 2-3); these have been grouped into four main categories for discussion in the following paragraphs.

Figure 2-3: Critical Success Factors for Effective Risk Management

SUPPORTIVE ORGANIZATION

A supportive organization behaves in such a way that it is seen to be fully behind risk management and all it entails. The organization “walks the talk.” It ensures that there are clear objectives for risk management and that these objectives are bought into by all stakeholders, who also contribute inputs and commit to using the outputs of the process. The organization allows time in the schedule for risk management, and it ensures that risk management occurs as early as possible in the project life cycle. The organization also provides the necessary resources and funding to carry it out. Supportive organizations recognize that the extra work identified to manage risks is fundamental to ensuring project success and needs to be adequately resourced. These organizations also accept the need to change in response to risk, and, where appropriate, provide a suitable contractual framework to enable the process.

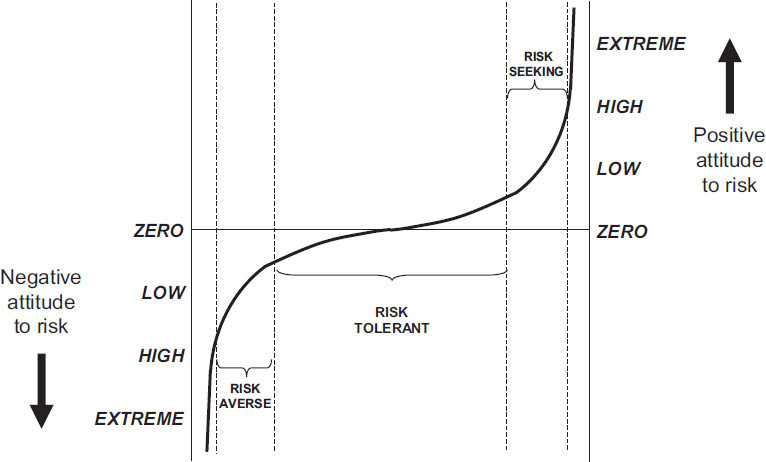

In the same way that individuals have an attitude to risk that affects their participation in the risk process, organizations also have a “risk culture” that reflects their preferred approach to dealing with uncertainty. There is a range of organizational risk cultures, as illustrated in Figure 2-4.

Figure 2-4: Range of Organizational Risk Cultures (based on Hillson and Murray-Webster 2007)

Organizations with a negative attitude to risk might be labeled as “riskaverse”; those with no strong response could be called “risk-tolerant”; “risk-seeking” organizations have a positive attitude toward risk. These cultures have a significant influence on the risk management process. For example, extreme risk aversion can sometimes develop into hostility: “We don’t have risk in our projects; we’re professionals/engineers/scientists. . . .” Denial results in important risks being ignored and decisions being made without cognizance of the associated risks. At the other end of the scale, the risk-seeking organization might adopt a “gung-ho” attitude to risk, which will likely lead to disaster if the amount of risk exposure taken on exceeds the organization’s ability to manage it.

The preferred risk attitude for an organization is neither risk-averse nor risk-seeking; rather, it is “risk-mature.” This attitude produces a supportive culture in the organization, which recognizes and accepts that uncertainty is inevitable, and welcomes it as an opportunity to reap the rewards associated with effective risk management. These organizations set project budgets and schedules with the knowledge that uncertain events can influence project progress and outcomes, but also with a commitment to provide the necessary resources and support to manage these events proactively. Project managers and their teams are rewarded for managing risks appropriately, with the recognition that some unwelcome risks occur in even the best-managed project.

Culture is the total of the shared beliefs, values, and knowledge of a group of people with a common purpose. Culture, therefore, has both an individual and a corporate component. For risk management to be effective, the culture must be supportive, meaning that individuals’ risk attitudes must be understood and managed, and the organization’s overall approach must value risk management and commit to making it work.

COMPETENT PEOPLE

For many people, risk management seems to be neither common sense nor intuitive. Project sponsors, project managers, team members, and stakeholders must be trained in applying the process, participating in it, or both. Training also needs to be at the right level and depth to suit the role involved. Effective training creates a shared understanding of the key concepts and principles of risk management. It enables the establishment of a common language and agreement on key risk management terms. Properly delivered training also helps to convince participants of the benefits of the process.

Training should not be viewed as a one-off event carried out when formal risk management is first introduced. It must be a continual process, bringing new members of the organization up to speed as soon as is practical. The end benefit of effective training is skilled and competent staff who contribute effectively to the risk process.

Attention should also be paid to ongoing competence development, with on-the-job training, job rotation, mentoring, and coaching, in addition to focused formal training courses. The aim is to develop practical skills as well as theoretical knowledge, encouraging effective behaviors and appropriate attitudes.

APPROPRIATE METHODS, TOOLS, AND TECHNIQUES

Different organizations may implement risk management in varying levels of detail, depending on the type of risk challenges they face. The decision about implementation level may also be driven by organizational risk appetite—the overall willingness or hunger to expose the organization to risk—and by the availability of funds, resources, and expertise to invest in risk management. The objective is for each organization to determine a level of risk management implementation that is appropriate and affordable. Having chosen this level, the organization then needs to provide the necessary infrastructure to support it.

Having selected the level of implementation, providing the required level of infrastructure to support the risk process is then possible. This might include choosing techniques, buying or developing software tools, allocating resources, providing training in both knowledge and skills, developing procedures that integrate with other business and project processes, producing templates for various elements of the risk process, and considering the need for support from external specialists. The required level for each of these factors will be different depending on the chosen implementation level.

Failure to provide an appropriate level of infrastructure can cripple risk management in an organization. Too little support makes efficient implementation of the risk process difficult, while too much infrastructure and process can be overly bureaucratic and fail to add value, in fact reducing the overall benefit. Getting the support infrastructure right is, therefore, a Critical Success Factor for effective risk management, because it enables the chosen level of risk process to deliver the expected benefits to the organization and its projects.

A SIMPLE, SCALABLE PROCESS

Risk management is not “one size fits all.” While all projects are risky, and risk management is an essential feature of effective project management, there are different ways of putting risk management into practice. At the simplest level is an informal risk process in which all the phases are undertaken, but with a very light touch. In this informal setting, the risk process might be implemented as a set of simple questions. For example:

• What are we trying to achieve?

• What could hinder or help us?

• Which of these are most important?

• What shall we do about it?

If these questions are followed by action and repeated regularly, the full risk process will have been followed, though without use of formal tools and techniques.

At the other extreme is a fully detailed risk process that uses a range of tools and techniques to support the various phases. For example, using this in-depth approach, stakeholder workshops might be used for the definition phase, followed by multiple risk identification techniques involving a full range of project stakeholders. Risk assessment would be both qualitative (with a Risk Register and various structural analyses) and quantitative (using Monte Carlo simulation, decision trees, or other statistical methods). Detailed response planning at both strategic and tactical levels might include calculation of risk-effectiveness, as well as consideration of secondary risks arising from response implementation.

Both of these approaches represent extremes, and the typical organization will wish to implement a level of risk management somewhere in between these two. These approaches do, however, illustrate how it is possible to retain a common risk methodology while selecting very different levels of implementation. Each organization wanting to adopt risk management consistently must first decide what level of implementation is appropriate.

A simple to use, scalable, and documented process ensures that each project does not have to work out the best way to apply risk management in its situation. An efficient procedural framework that supports the process and outlines “what to do” ensures support from the organization, and makes the most of the investment in training, tools, and techniques.

Conclusion

This chapter has presented some of the common difficulties expressed by people who feel that risk management belongs in the “too difficult” category. It also offered counterarguments to each objection, suggesting that attention to CSFs can make the difference between wasting time on an ineffectual process and implementing risk management that works. If any of these supporting elements (see Figure 2-5) are weak or missing, then the implementation of risk management becomes unstable and may even fall over.

Figure 2-5: Critical Success Factors to Support Effective Risk Management

Of the four groups of CSFs discussed, the one that seems easiest to address is the last—implementation of a simple, scalable process. This CSF allows project teams to apply risk management theory to their particular risk challenge. It also deals most directly with the main difficulty expressed by so many: “How exactly do we do risk management?” The rest of this book presents a detailed answer to this question, describing a simple, scalable risk process that can be applied on any project in any industry. The next chapter introduces this process, known as Active Threat and Opportunity Management (ATOM), and Part II of the book describes the ATOM process in detail.