16

The ATOM Risk Workshop

The risk workshop is central to the ATOM methodology, whether as a stand-alone facilitated meeting or as part of a regular project team meeting. It is the prime means by which risks are identified and prioritized. In some instances, the risk workshop is also used to develop risk responses. Chapter 5 (“Exposing the Challenge”) and Chapter 6 (“Understand the Exposure”) detail everything that should take place in a two-day risk workshop for a medium-sized project. In Chapter 13 (“ATOM for Small Projects”) and Chapter 14 (“ATOM for Large Projects”), we describe how the standard two-day risk workshop should be adapted to suit small and large projects. This chapter provides additional details on how the ATOM risk workshop is implemented in practice and how it might be varied in different circumstances. Figure 16-1 summarizes the scope of the risk workshop and risk meetings for projects of different sizes, as set out in the previous ATOM chapters. For this purpose, risk workshops are considered fully facilitated events, while risk meetings are often less formal and therefore unfacilitated, and may be included as part of a normal team meeting. Note that it is still expected that all risk meetings will be chaired by either the project manager or the risk champion.

When undertaking a risk workshop or risk meeting, there are a number of factors that need to be considered so that the best results are obtained. Perhaps the most important of these factors is facilitation—see Chapter 17 for more on facilitation. Other factors that need to be considered are detailed in the following paragraphs.

Variants on the ATOM Risk Workshop

While the focus of the ATOM methodology is primarily a facilitated two-day workshop, it needs to be recognized that taking two days out of many individuals’ working calendar can be both difficult and expensive. In addition, trying to arrange a two-day workshop when and where all necessary participants (team members and key stakeholders) can attend may take some time (perhaps weeks), and in doing so may actually be too late. Where this is the case, alternative approaches can be used.

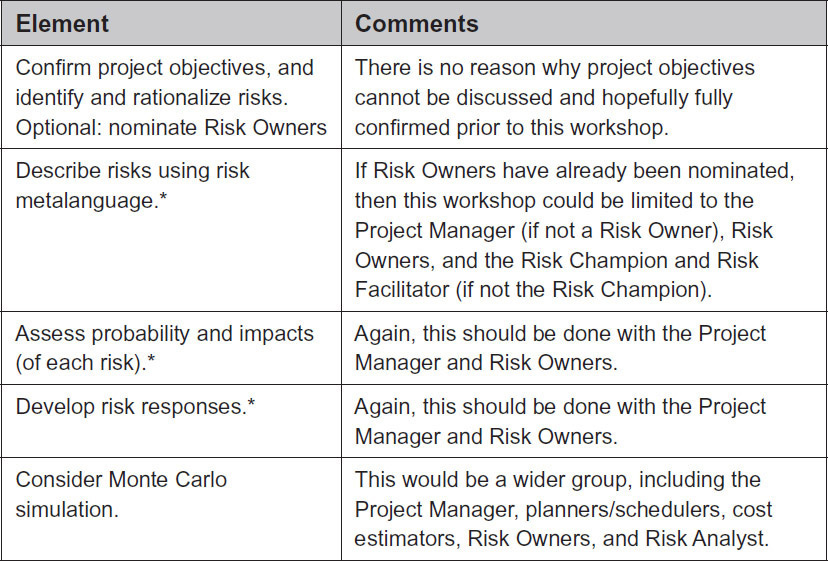

Figure 16-1: Scope of the ATOM Risk Workshop or Risk Meeting

PRE-WORKSHOP

Prior to attendance at the workshop, participants should be asked to do some preparatory work. This should not be a last-minute request. Ideally, this request should be made around seven days before the workshop takes place. This preparatory work should take the form of a series of questions. Here are some examples of the questions that could be asked:

• What might happen that would make it harder to achieve the project’s objectives?

• What might happen to make it easier?

• What assumptions are key to the project being a success?

• What constraints are having the greatest influence on the project?

A choice needs to be made as to whether this preparatory work is forwarded to the workshop facilitator in advance or brought along to the workshop by the participants. We recommend that it is forwarded in advance as this will allow the facilitator to consolidate the data received, so that it can be used in the early part of a standard workshop. Preparatory work will not only benefit a two-day workshop, but it will also benefit smaller, focused workshops.

SMALLER, FOCUSED WORKSHOPS

Facilitated risk workshops are both an efficient and an effective aspect of risk management. If desired, a full-blown, multiday risk workshop can be used to deliver the outputs listed below:

1. Confirm project objectives

2. Identify and rationalize risks

3. Describe risks using risk metalanguage

4. Assess probability and impacts (of each risk)

5. Categorize risks

6. Nominate risk owners

7. Develop risk responses

8. Consider Quantitative Risk Analysis.

However, achieving the outputs listed above would be time-consuming and would certainly take longer than the standard two-day workshop as it includes more elements. In many instances it will be beneficial to break the risk workshop into smaller, more manageable chunks while still achieving the same outputs (if required). These “chunks,” or smaller, focused workshops, should be kept to a maximum of three to four hours so they can be completed in either a morning or an afternoon. Figure 16-2 suggests the elements of a standard two-day workshop that can be dealt with in smaller, focused workshops.

REMOTE METHODS

Virtual Workshops Risk workshops do not need to take place face to face. Using interactive web-based software allows virtual risk workshops to take place. Such workshops are best used to identify risks but are less useful for risk assessment.

Virtual risk workshops need to be even more focused than a smaller, focused, face-to-face workshop. Constraints of the media being used, and the isolation of each participant, mean that they should ideally be kept to a maximum of two hours and be limited to eight to ten participants. Expert virtual facilitation is needed to make them work, and ideally they should be recorded for later analysis.

Free-for-all brainstorming doesn’t work, but hearing and perhaps reading (using some form of virtual messaging or whiteboard) what others have to say is still very important. The workshop facilitator will need to ensure that all participants contribute to the conversation, and if they don’t then they should be prompted to do so. The use of pre-work can put participants in the right frame of mind and perhaps form the basis for the early part of the discussion, and in this instance the pre-work should definitely be forwarded to the facilitator.

Figure 16-2: Elements of Smaller, Focused Workshops

* Note: These elements could also be achieved by directly interviewing Risk Owners and, where appropriate, Action Owners as well.

Before the workshop starts, the facilitator should read all the pre-work and also gain insight into each of the participants: where they work, what they do, how senior they are, and their level of experience. This will allow the facilitator to ask perhaps pertinent questions as the workshop proceeds. One facilitation tip for a virtual workshop is for the facilitator to imagine they are in a conference room with a large, round table. The facilitator should draw a circle on a large piece of paper and sit each participant around the table by writing their names in their “sitting positions.” As the workshop progresses, the facilitator can note who is contributing and who is not. Those who are quiet can be prompted to speak out. It also provides a constant reminder of who is in the workshop.

After the workshop is over, the facilitator should consider the notes they have taken and, if recorded, listen to the recording to document the outcomes of the workshop. This should be in the form of a report accompanied by an initial list of risks. It is not appropriate to provide an exact list of contents for the report, but it should include the names of those who attended, their role, function, and so on, and, where valid, the main points raised earlier regarding what might make it harder or easier to achieve the project’s objectives, as well as key assumptions and greatest constraints. It should conclude with any follow-up actions that have been agreed upon. The list of risks should include the risk descriptions, using risk metalanguage, and any other salient information, for example, the proposed risk owner.

The list of risks can then be used to populate the risk register and form the basis for risk assessment. It is not recommended that risk assessment be carried out in the same e-meeting. Risk assessment usually involves a small number of people such as risk champion, risk owner(s), and project manager, and it is likely that the majority of attendees will be unable to contribute. Therefore, risk assessment would be best carried out by interview, either by telephone or face to face, or a by conference call when more than two people need to be involved.

The Delphi Technique There are instances where it is either impractical or impossible to get all necessary participants together, even for a two-hour virtual workshop. The Delphi technique is a method that can be used in such circumstances.

The Delphi technique was originated at the Rand Corporation as a means of predicting the consequences of the then current policy decisions. The technique lends itself to risk management, and in particular to risk identification and the assessment of risk events. The Delphi technique operates by using a qualified group to gather and respond to opinions. An advantage is that it can be carried out remotely and/or anonymously, such as by email or in real time using online platforms. This overcomes some of the group biases and logistical limitations of a facilitated workshop, while retaining at least some scope for the exchange of ideas. The Delphi technique can be quite time-consuming if not managed appropriately. Consequently, experience also shows that more than two rounds of data gathering can result in a high dropout rate among participants.

The Delphi technique can be used in situations where the people needed to take part in risk identification (or assessment) are geographically dispersed and where it would be too expensive to hold a face-to-face workshop, or where running a virtual workshop is inconvenient due to time differences. In using such a process, it is vital that no individual is ever aware of any other individual’s inputs, that is, who identified which risk.

A typical approach to risk identification using Delphi would be to email all participants a pro forma (see Figure 16-3) for them to fill in and return via email. Once all inputs are received, the risk champion should prepare a consolidated list (removing non-risks and duplicates while ensuring that all risks are described properly using metalanguage). The consolidated list should then be emailed back to all participants for review, comment, and the identification of further risks prompted by the review. As previously mentioned, it is important that no participants know who identified each individual risk. Once returned for the second time, the risk champion can prepare a final list of risks that can be taken further into the ATOM process.

Using the Delphi technique for risk assessment can follow almost the same process as for risk identification, but the two must not be carried out at the same time. Doing the assessment at the same time as identification can become a distraction and reduce the quality of both processes. The consolidated list of properly described risks from risk identification will form the input to the assessment. However, rather than sending the complete list to a wide group, a subset of risks should be sent to those with particular expertise in that subset. This would include those who identified the risks, potential risk owners (this may be the same person who identified the risk), and other interested parties, as determined by the project manager and risk champion.

Figure 16-3: Pro Forma for Risk Identification Using the Delphi Technique

Each contributor should be asked to suggest the probability and impacts for each risk, where they believe they can. “Dont know” is a valid response. As in risk identification, this should be done using a pro forma that includes the risk description but extends to include the probability and positive or negative impacts on each of the agreed-upon project objectives. Comments will also be allowed.

Once returned, the risk champion will again consolidate the inputs, and where there is general agreement on probability and impact, take no more immediate action. Where there is disagreement, the risk champion should work with the chosen risk owner to finalize the probability and impacts to be used going forward, while considering all inputs.

While this section discusses using email as the mechanism to enable use of the Delphi technique for risk identification and assessment, it is recognized that other approaches and platforms can be used, including apps and social media. The risk champion should be aware of such tools and consider whether their use would be more appropriate than email and also of benefit to the ATOM process.

Assessment of Probability and Impacts during the Assessment Step

FACTORS INFLUENCING THE RISK WORKSHOP

There has been and continues to be considerable debate on the best way to assess risks, and in particular whether probability and impact should be assessed at the same time or separately, and if separately, which one should come first.

Probability and Impact at the Same Time Assessing probability and impact together may seem the most natural thing to do. Unfortunately, there can be an undesired side effect of doing this. Humans are known to play down the chance of adverse events as part of survival instinct: “If it’s really bad, it probably won’t happen to us.” Evidence exists that when a threat with a potentially very high impact is identified, the chance of it occurring is always perceived as being very low. The same can be said for opportunities. If an opportunity was identified that could save 50 percent of the project budget, then team members are likely to be skeptical and conclude that it is highly unlikely, even if that isn’t the case.

Having said this, the quickest way to assess risks is indeed to consider probability and impact together for each risk in turn, and then move on to the next risk. When this is done, the facilitator must look for any biases that are in play and try to overcome them; see below.

Probability First For each risk, looking at probability first, and once agreed-upon, looking at impact second can remove the bias that says if the impact is really bad, it won’t happen to us. This method is also our recommended approach.

• The probability of occurrence is first estimated using the agreed-upon set of probability definitions, for example, very high, high, medium, low, or very low. Since a risk is an uncertain event or set of circumstances, it has just one probability, representing the level of uncertainty associated with the risk.

• Second, the participants in the meeting or workshop imagine that the risk occurs, and determine its impacts on project objectives, again choosing from the agreed-upon set of defined scales, for example, very high, high, medium, low, or very low. Of course, a risk may have different levels of impact on different objectives; for example, a risk may have a medium probability of occurrence, and if it happened, it might then have a low impact on project timescale, high impact on project budget, and no impact on quality.

Impact First Not only can a risk affect multiple objectives, it can also have a range of impacts on those objectives. For example, consider a risk that there might be a delay in the delivery of a key piece of equipment that would lead to an overall schedule delay of one to eight weeks. The probability of a one-week delay is likely to be higher than for an eight-week delay. Agreeing on the impact before the probability overcomes this complication. (In quantitative risk analysis this complication is overcome by allowing risks to have a range of impacts modeled by the use of a distribution curve, as discussed in the previous chapter.)

A variant of looking at probability and impact separately is to have two separate groups looking at each aspect and then combining the results. This can lead to some very interesting discussions in respect to the probability of high or very high impact risks. This is particularly true where very high impact risks have been assessed as having a probability of medium or higher (see above discussion on playing down the chance of adverse events). This can lead to pressure to reduce the probability of high or very high impact risks, which of course should be resisted, as this would make the process meaningless.

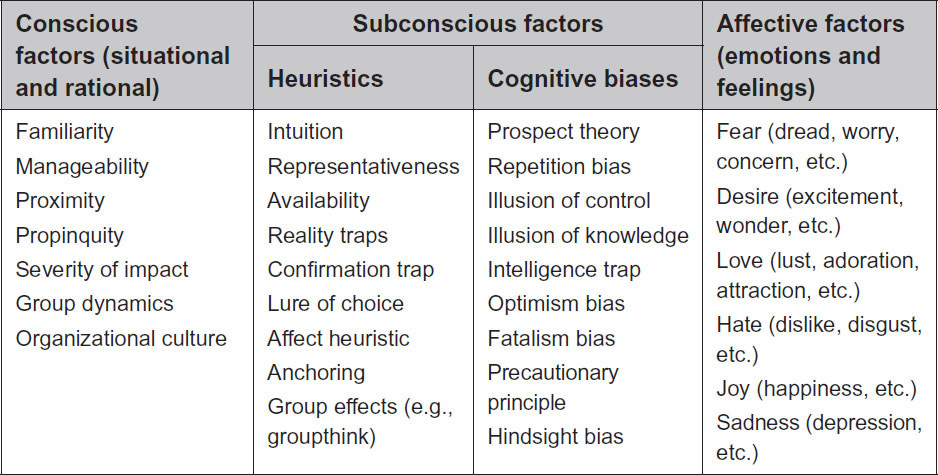

THE EFFECT OF SUBCONSCIOUS BIASES

Subconscious biases can have a marked effect on the ATOM process, in particular on identification and assessment. A facilitator must be able to identify any subconscious biases that might arise from perceptual factors or heuristics. Heuristics are shortcuts or “rules of thumb” used to make decisions or judgments in cases of uncertainty. Three common heuristics that might operate in the identification and assessment step are:

• Representativeness (or “the same risk will always occur in similar circumstances”). Although this might be true, it might not take into account any local differences or changes in circumstances.

• Availability (or “most recent is most memorable”). A person’s belief that a risk has a high probability or high impact may stem from the risk having occurred recently in their experience.

• Anchoring and adjustment (or “the first answer is always nearly right”). This can make the group reluctant to disagree on or change the first value expressed by someone, even if they feel it is wrong.

Knowledge of heuristics allows the facilitator to identify when they are coming into play. When the facilitator believes that one or more heuristics is in evidence, he or she should challenge workshop attendees. This must be done sensitively, without personal criticism or offense, by using questions such as the following:

• Representativeness

• When was the last time you experienced this risk?

• Could things have changed since then?

• Availability

• When did that risk last occur? And previous to that?

• Could it really happen again on this project?

• Anchoring and adjustment

• Are you sure? Why do you say that?

• What do the rest of you think?

In addition to the three common heuristics described above, there are many other influences on the perception of probability and impact as well as risk in general. These can be grouped under three headings: conscious factors, subconscious factors (which include heuristics and other cognitive biases), and affective factors (see Figure 16-4). Awareness of these can further improve the overall facilitation of the risk management process and its effectiveness.

Figure 16-4: Common Influences on Risk Perception (adapted from Murray-Webster and Hillson 2008)

Conclusion

The risk workshop is central to the ATOM process and can take the form of a fully facilitated or as part of a routine meeting. It therefore needs to be conducted in a manner that ensures successful outcomes. In order to do this, it must be properly facilitated (see Chapter 17) and specific approaches adopted, in particular relating to the assessment of probability and impact. Additionally, the effect of subconscious biases must be acknowledged and, where possible, dealt with by the facilitator.

While the risk workshop is central to ATOM, it is recognized that carrying out a two-day, face-to-face workshop (or meeting) may not always be possible. In order to reduce the time spent face to face, more work can be done pre-workshop. Workshops can also be smaller and focused on particular steps of the ATOM process.

Where it is impossible or impractical to meet in a face-to-face event for half a day, then remote methods need to be considered, such as web-based virtual workshops for risk identification or the Delphi technique for risk identification and assessment.