3

Active Threat and Opportunity Management—The ATOM Risk Process

The benefits of formal risk management are undeniable and clear for all those who care to see. Even though this fact is recognized by many organizations, the reality is that risk management is rarely implemented effectively, often despite well-defined processes, the existence of proven tools and techniques, and many training opportunities for those who need it. If this is the case, then where is the problem? It appears that ineffectiveness stems largely from project managers and their teams not knowing how to actually do risk management. Clear, practical “how-to” guidance is obviously needed; this also meets one of the four Critical Success Factors (CSFs) for risk management outlined in the previous chapter: a simple to use, scalable, and documented process that removes many of the barriers to the use of risk management for projects and provides invaluable help to those who believe it to be important but are struggling to make it effective.

First, we must determine what such a simple, scalable process should cover. A number of important steps must be included:

• If risk is defined as “any uncertainty that, if it occurs, would have a positive or negative effect on achievement of one or more objectives,” then clearly the first step in a risk management process is to ensure that the objectives at risk are well defined and understood. These objectives might have been clarified outside the risk process (for example, in a project charter, business case, or statement of work), but risk management cannot begin without them, so if there is no clear list of project objectives, the risk process must produce one.

• After defining objectives, determining the uncertainties that might affect them is possible. As discussed in Chapter 1, potentially harmful uncertainties (threats) must be identified, as must those that might assist the project in achieving its objectives (opportunities).

• Of course, not all of the uncertainties identified in this way are equally important, so the risk process must include a step for filtering, sorting, and prioritizing risks to find the worst threats and the best opportunities. Examining groups of risks to determine whether there are any significant patterns or concentrations of risk is also useful. It might also be good to determine the overall effect of all identified risks on the final project outcome.

• Once risks have been identified and prioritized, the risk challenge faced by the project will be clear and the risk process can move from analysis to action. At this point attention turns to deciding how to respond appropriately to individual threats and opportunities, as well as considering how to tackle overall project risk. A range of options exists, from radical action such as canceling the project to doing nothing. Between these extremes lies a wide variety of action types: attempting to influence the risk, reducing threats, embracing opportunities, etc.

• The important step of planning responses is not enough to actually change risk exposure, of course; it must be followed by action, otherwise nothing changes. Planned responses must be implemented in order to change the risk exposure of the project, and the results of these responses must be monitored to ensure that they are having the desired effect.

• These steps in a risk process might be undertaken by just a few members of the project team, but the results are important for everyone, so it is essential to communicate what has been decided. Key stakeholders should be kept informed of identified risks and their importance, as well as what responses have been implemented and the current risk exposure of the project.

• Clearly the risk challenge faced by every project is dynamic and changing. As a result, the risk process must continually revisit the assessment of risk to ensure that appropriate action is being taken throughout the project.

• A fully effective risk process does not end at this point, because the learning organization wants to take advantage of the experience of running this project to benefit future projects. The normal Post-Project Review step must, of course, include risk-related elements so that future threats are minimized and opportunities captured in the most efficient and effective manner.

Introducing ATOM

The logical story outlined above is not rocket science, but it does offer a simple, structured way to deal with the uncertainties that might affect achievement of project objectives. Any project risk management process should follow these eight steps:

1. Define objectives

2. Identify relevant uncertainties

3. Prioritize uncertainties for further attention

4. Develop appropriate responses

5. Report results to key stakeholders

6. Implement agreed-upon actions

7. Monitor changes to keep up to date

8. Learn lessons for the future.

Active Threat and Opportunity Management (ATOM) is designed to meet the need for a simple, scalable risk management process and to be applicable to all projects. It also embodies the steps described above in a generic risk management process that can be applied to all projects in any industry or business sector, whatever their size or complexity. ATOM brings together recognized best practices and tried and tested methods, tools, and techniques, combining them into an easy-to-use yet structured method for managing project risk.

The ATOM process is composed of the following eight steps:

1. Initiation

2. Identification

3. Assessment

4. Response Planning

5. Reporting

6. Implementation

7. Review

8. Post-Project Review.

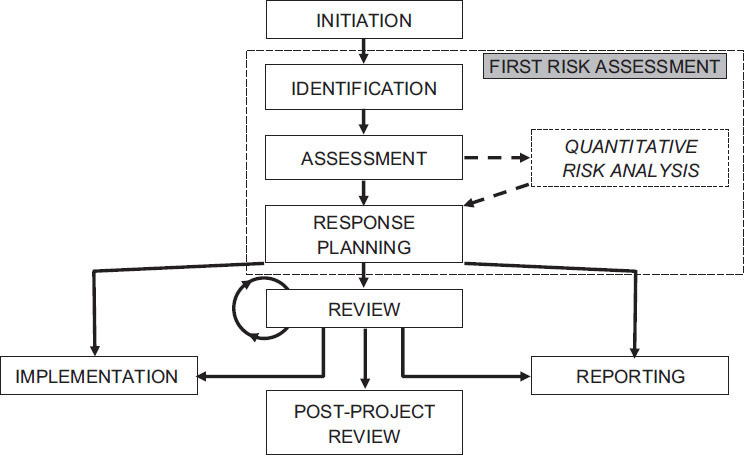

The Assessment step might also include quantitative risk analysis (QRA) to determine the effect of risks on overall project outcome, though this is not always required (as discussed below). Figure 3-1 shows how these steps fit together into a cohesive process, which is described in detail later in this chapter.

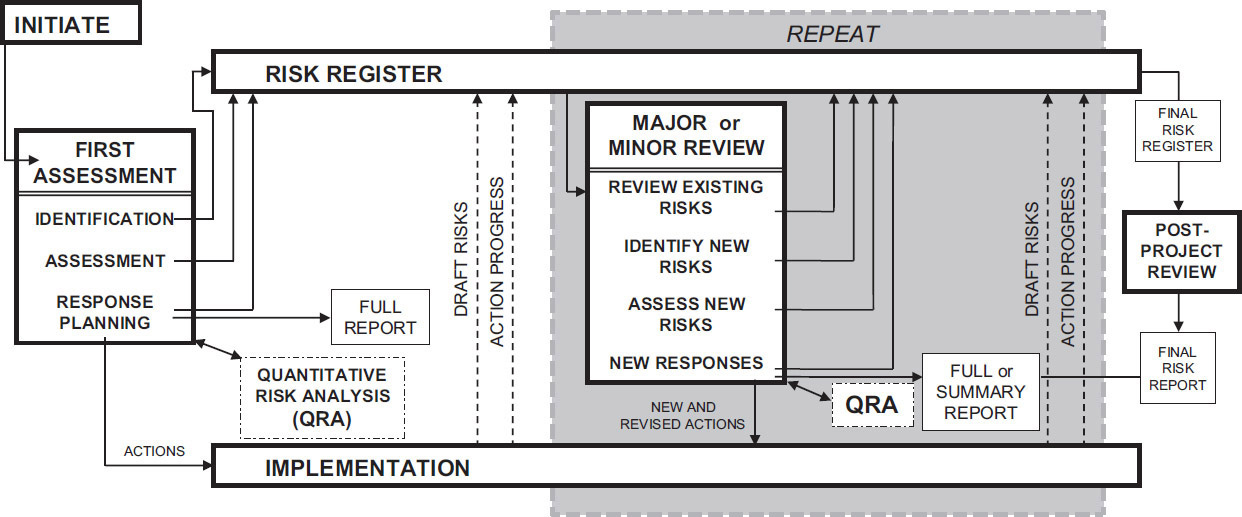

Of course, risk does not appear just at the beginning of a project and then go away, so a risk management process cannot be performed just once. The ATOM approach recognizes the undeniable need to carry out risk management throughout the project life cycle, from concept to completion, or from the business justification to handover, as shown in Figure 3-2. Risk management is all too often seen as something done at the beginning of the project and then cast aside as other “proper project management processes” take over. This is clearly wrong. ATOM demands that, following an initial risk assessment, a series of reviews are undertaken through the life cycle of the project to keep the process alive. It is also important to recognize that part of any project’s value is the organizational learning it offers to the business, which is why ATOM places emphasis on lessons learned as an essential part of project management. The ATOM risk management process also includes a final step to capture risk-related lessons at the end of a project, concluding with a formal Post-Project Review.

Figure 3-1: Steps in the ATOM Process

Figure 3-2 shows how the ATOM risk process might be conducted through the various phases of the project life cycle. For most projects, ATOM starts before the project is sanctioned or approved, by undertaking the Initiation step, leading to a Risk Management Plan, followed by a First Risk Assessment to determine the risks associated with implementing the project. After the project sanction or approval, ATOM continues with a series of reviews throughout the project life cycle. The project life cycle is different for a contracting organization, which bids for work and only conducts the project if it wins it. For some contractors, ATOM starts when they win the work, which is when they undertake the Initiation and First Risk Assessment steps. For other contractors, ATOM starts during the bid process and is an integral part of putting the bid together. It is likely that a contractor that carries out Initiation and First Risk Assessment as part of the bid process will repeat the process if the bid is successful.

Figure 3-2: ATOM Steps through the Project Life Cycle

Project Sizing

No two projects are the same. Projects vary vastly in size and complexity. Some projects are started and finished in a few weeks, while others take a decade or more to complete. Some projects have budgets of a few thousand dollars (or even no budget at all), while others cost billions. Some projects are relatively routine, using tried and tested strategies, while others are totally innovative and groundbreaking.

In response to this wide variety of projects, ATOM offers a fully scalable risk management process that recognizes that simple or low-risk projects may need just a simple risk process, while complex or high-risk projects require more rigor and discipline. ATOM provides scalability in three ways: through the number and type of reviews required during the project life cycle, through the optional use of QRA techniques, and through the range of tools and techniques used during each of the ATOM steps.

• Reviews. Sometimes simply revisiting the risk process to determine changes to existing risks and whether any new risks have arisen is sufficient. At other times a full repeat of the entire risk process might be appropriate. ATOM uses two types of reviews to meet these needs: a Major Review and a Minor Review. These can be used in various combinations depending on the size of the project.

• Quantitative risk analysis (QRA). ATOM suggests reserving use of QRA for projects that are large or high-risk, where the investment in such techniques can be justified.

• Tools and techniques. Many techniques exist for the identification and assessment of risks. An appropriate set of techniques should be selected to meet the risk challenge of a particular project.

Figure 3-3 presents the full scalable ATOM risk process, indicating where reviews and QRA might occur.

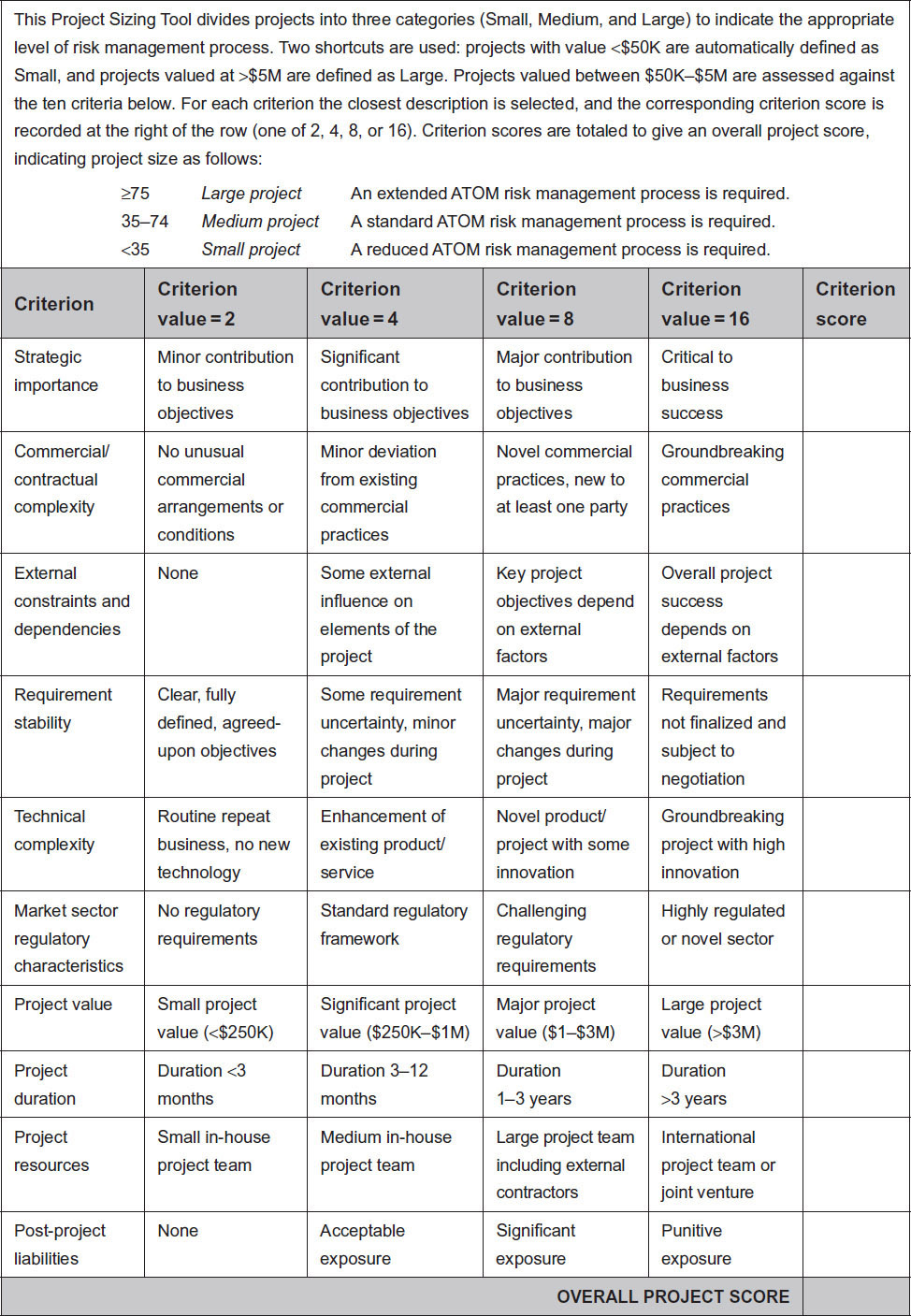

With a scalable process, a method of deciding what level of process is appropriate for any particular project is clearly important. “Project size” is a multidimensional concept, with many factors to be considered. It is also a continuous variable, rather than one with a small number of discrete values. However, it is useful to have a simple tool that uses various criteria to characterize a given project, perhaps dividing projects into three groups that we can call small, medium, or large. This tool has several uses, not just relating to risk management, because many project management processes can also be scalable depending on the size of the project.

One key question is how many criteria should be used in such a sizing tool. If too few criteria are used, then it is difficult to distinguish between projects of different sizes. On the other hand, too many criteria can become overly complex and can lead to insufficient discrimination due to the averaging effect. Experience suggests that using 10 to 12 criteria is about right, giving a good compromise between detail and usability. Each organization should define those criteria that best describe the relative size and importance of a project within the business. One organization’s “small” will be another organization’s “large.”

Even where sizing criteria are well defined, an organization may wish to allow shortcuts to describe circumstances in which project size can be determined without use of the project sizing tool. For example, projects of very low value or very short duration might always be deemed small, while business-critical projects might always be large.

Figure 3-4 presents a sample project sizing tool to illustrate the approach that an organization might adopt in order to size a project. This example uses a Likert scale to translate qualitative descriptions of the sizing criteria into quantitative values that can be combined into a sizing score. Thresholds are then set to define small, medium, and large. Any given project can then be scored against the criteria in order to determine its size.

The example in Figure 3-4 is specific to a particular business, but can be tailored by another organization to include those criteria that reflect the types of projects it undertakes, because the general principles should apply. Other criteria could include “relationship with other projects,” “exposure to the wider business,” or “political sensitivity.” Note that the numerical thresholds used in the example in Figure 3-4 are scaled to work with 10 criteria and must be adjusted if more or fewer criteria are used.

Of course, there are exceptions to every rule, and it is important not to be process-driven when making important decisions on projects. There will always be projects that score as medium or small using a project sizing tool, but that are so strategically important or commercially sensitive that it would be foolhardy not to treat them as large. Such decisions to contradict the output of the project sizing tool should only be made by the project sponsor in consultation with the project manager.

Figure 3-3: The Full ATOM Process

Figure 3-4: Example Project Sizing Tool

Most project-based organizations have a portfolio of projects of various sizes, including small, medium, and large ones, all of which require active management of risk, though at different levels. A reduced level of risk management attention is appropriate for small projects because they matter less to the business and the potential for variation is usually small. By contrast, large projects require a higher level of risk management attention because any variation is likely to be significant.

The typical ATOM process is designed for medium-sized projects, though it is scalable for small and large ones. Taking the basic ATOM process as shown in Figure 3-3, the main differences for the three project sizes are as follows:

• Small projects require a reduced ATOM risk management process that is integrated into the normal day-to-day management of the project without using dedicated risk meetings.

• Medium projects require the application of the standard ATOM risk process with risk-specific activities in addition to the normal project process. These are led by a risk champion who oversees the use of specific risk meetings, including workshops, interviews, and ongoing reviews.

• Large projects require an extended ATOM process, which includes QRA and a more rigorous review cycle in addition to the elements applied for medium projects.

It is important for the depth of the risk process to match the risk challenge of the project. For example, applying a reduced risk process to a medium or large project is likely to result in failure to properly resource the process and ineffective management of risk.

The ATOM process for a medium-sized project is described in detail in Part II (Chapters 4 through 12) and is summarized below. Recommended variations in using ATOM for small and large projects are covered in Chapters 13 and 14, respectively.

ATOM for the Medium-Sized Project

The ATOM process for a medium-size project requires a structured approach, as follows.

Like most other risk management processes, ATOM starts with an Initiation step. This step, described in Chapter 4, considers project stakeholders and their relationship to the project. A fundamental part of the Initiation step is confirmation of the project objectives to ensure that they are clearly understood and documented, and as a result the uncertainties that matter can be determined and subsequently prioritized. The size of the project, and therefore the degree to which ATOM should be applied, is also confirmed. Initiation culminates with the preparation of a Risk Management Plan.

This is followed by three sequential steps that make up the First Risk Assessment, namely Identification, Assessment, and Response Planning. A formal two-day risk workshop is used to identify project risks (see Chapter 5) as well as to assess their probability and impacts against predefined scales as set out in the Risk Management Plan (see Chapter 6). The aim of the Identification step is to identify and properly describe relevant uncertainties, including both positive opportunities and negative threats that could affect project objectives. Assessment provides the means to determine which uncertainties matter most to the project, by considering the probability of the risk occurring and its potential impact on the defined project objectives. During Identification and Assessment, all identified risks and their assessment data are recorded in a newly created project Risk Register. Following the risk workshop, Response Planning takes place via a series of interviews with identified Risk Owners, during which responses are identified with their associated actions (see Chapter 7). The appropriateness of the response is paramount to this step to ensure that responses are not only physically effective but also timely and cost-effective.

Once the First Risk Assessment step is complete, the next two steps in the ATOM process take place in parallel. A risk report documenting the results from the First Risk Assessment is prepared and disseminated to those who need to receive it; this Reporting step is described in Chapter 8. Reporting is one of the ways in which the dynamic nature of risk is communicated, because reports highlight significant changes to project risk exposure.

At the same time as the Reporting step, the ongoing step of Implementation of responses via their associated actions also starts (see Chapter 9). Implementation of responses continues throughout the project, only concluding when the project ends. Without effective implementation, the risk exposure of the project remains unchanged.

Fundamental to keeping the process alive throughout the project life cycle is the use of formal risk reviews. At predetermined points in the life cycle, as set out in the Risk Management Plan, a Major Review (see Chapter 10) takes place that includes the same elements as the First Risk Assessment but on a reduced scale. All key stakeholders attend a risk workshop to review existing risks, and to identify and assess new risks, resulting in an update to the Risk Register. Risk responses and their associated actions are identified by interviewing Risk Owners as soon as possible after the risk workshop. Agreed-upon responses and actions are recorded in the Risk Register. New and revised actions are implemented through the ongoing Implementation step. A full report is produced at the end of the Major Review.

At regular points in the project, usually in line with the normal project reporting cycle, risk management is formally revisited as part of a Minor Review (see Chapter 11). A Minor Review may take place as part of a normal project review or as a separate meeting. During a Minor Review all high-priority risks are reviewed, new risks are identified and assessed, and responses are planned; the Risk Register is then updated. As for the Major Review, new and revised actions are implemented through the ongoing Implementation step. A summary report is produced at the end of each Minor Review.

The ATOM process concludes either at the formal Post-Project Review meeting or at a separate meeting, during which a “risk lessons learned” report is produced and the final Risk Register agreed upon. Chapter 12 describes this conclusion to the ATOM process.

The ATOM process for the medium-sized project is purely qualitative, with no use of statistical processes to predict the overall effect of risk on project outcome. QRA techniques are an important part of project risk management, but ATOM suggests that they should only be mandatory for large projects. This does not, however, mean that QRA cannot be used effectively on medium or even small projects, but this analysis should be at the discretion of the project manager and considered during the ATOM Initiation step. QRA is valuable because it models the effect of identified risks on the project schedule and budget, calculating the range of possible completion dates (and interim milestones) and final project cost. It is also possible to predict ranges of outcomes for other project criteria, such as net present value (NPV) and internal rate of return (IRR). This information can be beneficial when determining the correct strategy for the project and for understanding the effects of managing individual risks. Chapter 15 describes how to apply QRA to projects.

Comparison to Existing Standards

There are a number of standards documents in the project risk management area, offering different approaches to the subject, as well as more general risk standards that include projects in their scope. The most popular of these include:

• ISO 31000:2018—Risk Management—Guidelines, from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

• Management of Risk (M_o_R), from the UK Office for Government Commerce (OGC)

• The Standard for Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs and Projects, from the Project Management Institute (PMI®)

• Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), from the Project Management Institute, particularly Chapter 11, “Project Risk Management”

• Project Risk Analysis and Management (PRAM) Guide, from the Association for Project Management (APM)

• Risk Analysis and Management for Projects (RAMP), from the UK Institution of Civil Engineers, Faculty of Actuaries and Institute of Actuaries

• BS IEC 62198:2014—Managing Risk in Projects—Application Guidelines.

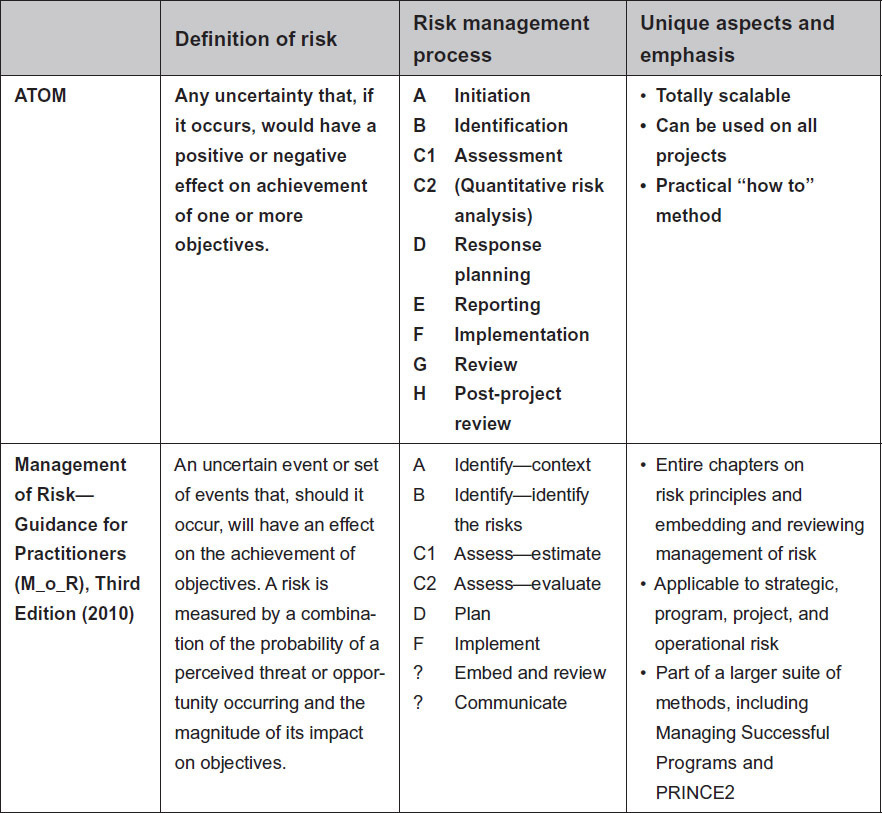

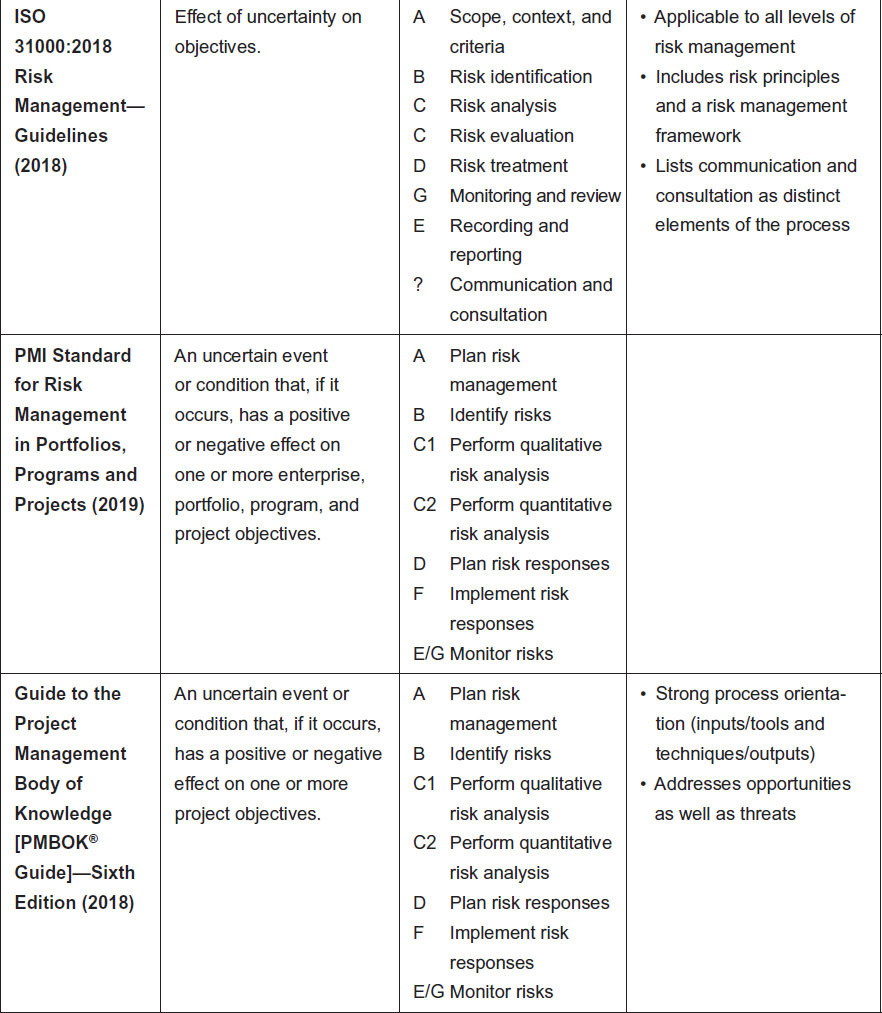

Although there are several different standards covering the topic, there is good agreement between their content, with the main differences being the terminology used. Those familiar with these standards should have no problem in understanding or applying the ATOM process, since it is fully consistent with them all. The key differences between ATOM and the other standards are summarized in Figure 3-5, which compares their use of terminology, the different constituent stages of each process (mapped to ATOM steps labeled as A–H), and the unique aspects of each approach.

Figure 3-5: Comparison of Different Standards

The fact that ATOM is consistent with the main project risk management standards raises the question of why it should be used instead of what already exists. The main difference is that ATOM is not a standard. Instead, it is a practical method that describes how to do risk management for a real project, rather than a theoretical framework or set of principles. It is intended to make project risk management accessible to all and easy to use, with enough detail to support practical implementation on any project in any organization or industry type.

Conclusion

One of the main Critical Success Factors for effective risk management is a simple, scalable process. ATOM offers such a process, and following it allows any organization to identify and manage risks to its projects in a way that is appropriate and affordable. Using ATOM provides assurance that the main risks will be exposed, thereby minimizing threats, maximizing opportunities, and optimizing the chance of achieving project objectives.