Chapter 2

What Is Driving Private Banking?

There are numerous forces at work shaping the private banking industry. Market volatility following the financial crisis of 2008 has led to a demand for simpler, more transparent types of investments among clients. Regulatory matters are also affecting the business. Concerns about the safety and soundness of banks have increased the pressure for stricter regulations to protect clients and to ensure that banks are adequately capitalised. As for clients, growth in nontraditional markets along with a shift taking place as a new generation takes over wealth planning also have affected how the business develops.

Competition, too, is undergoing change. Today’s competitor is no longer interested only in clients but also in securing the necessary talent to serve these clients in a market in which demand for relationship managers has increased. Where capital is concerned, banks that can demonstrate that they are able to exceed regulatory minimum requirements are at an advantage. Those that lack capital or the size necessary to compete in new markets are likely to join a wave of consolidation already underway in the industry.

How these forces together are shaping the industry makes private banking both exciting and challenging. The clock cannot be turned back. Private banks must accept that the world is changing and must seek to adapt. This chapter explores the issues that are critical for an understanding of how the industry will evolve in the future and to answering the questions that must be addressed to succeed in this new environment.

AN INDUSTRY IN THE MIDST OF CHANGE

Private banks are among the few service providers just as relevant to clients now as they were decades or even a century ago. In today’s dynamic marketplace, changes on numerous fronts are profoundly affecting how these banks approach their business. To take advantage of opportunities and anticipate risks, it is becoming increasingly important to assess the forces shaping the industry. This is done to get a clear idea of what lies ahead and which areas might offer the best avenues for growth. Due to its global nature, private banking is influenced by developments all over the world, in virtually every market and in real time. Today, it is no longer enough to wait for events and then respond to them. It is vital to understand the trends sweeping through the industry. Numerous factors come into play. The rising level of wealth in emerging markets has altered the client mix, making the business more interesting and varied. At the same time, it adds a new layer of complexity. Intense competition in some markets is challenging both new and established players. The financial crisis has led to a host of initiatives aimed at reducing risks, adding to an already intricate set of rules and regulations. Meanwhile, governments, concerned about undisclosed assets, are stepping up pressure on private banks to divulge information on assets that are held cross-border.

Although the private banking business model and geographic focus might undergo occasional changes, the central focus of the business remains the same. Its main goal continues to be to ensure that the wealth of clients is preserved, not just for a few quarters but for generations, providing growth on a sustainable basis without jeopardising assets. Delivering a high standard of service in a sustainable way, meeting and trying to exceed client expectations, maintaining their privacy, serving them with integrity, and deserving their trust remain the raisons d’être of any private bank. Due to the internal and external forces affecting the industry, private banks must make choices and take decisions now that will have a far-reaching impact for years to come in order to best serve new and existing clients. The speed at which events unfold today along with the implications that developments may have means that any actions must be carefully weighed. It is important to plan and to act when necessary, rather than face an uncertain future.

A note here is in order regarding the term “private banking.” Traditionally private banking was viewed as a sub-service of wealth management, a category that could include many other types of businesses. Today, however, private banking is often used as a term interchangeable with wealth management. Unless a clear distinction is made, this book uses both of these terms to describe the activity of managing the wealth of high-net-worth individuals.

The next section of this chapter looks at the key forces having the greatest impact on how private banking is developing from a business perspective. The four drivers—markets, regulatory environment, clients, and competition—are the main forces that are shaping the industry today and most likely will be for years to come. To gain a better understanding of what these factors are and their potential impact, this chapter touches on many of the main themes that are explored in greater detail elsewhere in this book.

Swiss Industry, International Perspective

Switzerland has a long history as a financial centre. The country’s financial industrya accounts for 10.7 percent of the GDP and employs in total nearly 246,000 people both within and outside of Switzerland. The financial centre pays each year an estimated 14 billion to 18 billion Swiss francs in taxes, equal to 12 to 15 percent of total tax revenue.(1) Swiss private banking enjoys a reputation unparalleled in terms of quality and client discretion. The country’s modern and efficient infrastructure, educated population, sound currency, and stable government all contribute to its attractions as a banking centre. The Swiss law governing banking secrecy, adopted in 1934, though subject to much debate over the years, has certainly played a role as well.

Switzerland, with a population of about 7.8 million people, roughly equal to that of Greater London, provides only a small home market. The strong growth of private wealth during the 1990s led many Swiss and foreign banks, especially larger players, to expand their private banking operations on an international basis, both onshore and offshore.b Where the larger Swiss banks are concerned, this means going to where their customers are, including both Europe and some rapidly growing emerging markets.

Changes in the regulatory environment at home and expanding wealth in emerging markets are factors that are leading Swiss banks to rapidly expand their international presence, especially in Asia. A survey conducted by the University of St. Gallen found that no less than 63 percent of Swiss banking CEOs believed that having an international presence would be “important” or “very important” for private banks in the future. Furthermore, nearly two-thirds of CEOs “effectively believe that banks that increase their international presence meet a precondition for future success in private banking.”(2)

Evolution of the Business Model

Providing personalised money management and advisory services to wealthy individuals or families is what a private bank does. But defining what a private bank is, in terms of its business model, is more difficult. Today there is a diverse set of models under which private banking services are offered. In Switzerland, the classic definition of a “private bank” is one in which its owners are partners who share unlimited liability. This type of structure has become increasingly rare over the years. In 2010 there were just 12 such private banks in Switzerland matching this description.c The classic private banking model aims to provide integrated services, meaning offering only products developed by the bank itself. Such an approach encompasses all parts of the value chain (production and delivery).

A key reason for taking this approach has been privacy. In other words, private banks saw a risk in having client information handled by outside parties. Beyond that, it was considered “a sign of weakness” if external products were employed, according to a study published by Hans Geiger, a professor of banking at the University of Zurich, and Harry Hürzeler, managing director of the Swiss Banking School.(3) Things have changed, however. One reason is that clients’ needs have become more complex and sophisticated. This affects their requirements regarding financial expertise, taxation, and legal compliance. The range of product offerings and services likewise demands increasingly specialised know-how. A model whereby a single private bank offers the best possible solutions in all categories is growing less feasible. In fact, today third-party products and services are a sign of strength, in that they give clients what truly represents the top of the range in terms of quality.

This is leading to a business model that more often is characterised by different forms and various types of ownership. A private bank today might be owned by partners in the traditional sense, or it might just as easily be part of another, larger publicly traded financial group. Such an institution may offer private banking as its sole dedicated service, as a so-called pure-play private bank. Alternatively, private banking may be one of a number of multiple services offered to clients on an integrated basis, alongside asset management, investment banking, and retail services. In Switzerland, private banking can also be offered by regional banks in which the Swiss cantons hold a majority stake, serving both retail and wealthy clients. To add to the complexity, private banking services even might be by “non-banks” or companies having their core competencies in different fields, such as independent asset managers or insurers. Thus, while there may be only a few independent private banks in the traditional sense, the private banking industry in the broader sense has grown tremendously in size and scale, reflecting its attractiveness as a business, along with the increase in the level of overall wealth, which has drawn a variety of companies to this industry.

Global Financial Centres

As part of their activities, most private banks engage in cross-border business. Offshore wealth management comprises a significant share of global wealth. According to the Boston Consulting Group, the offshore component was estimated to amount to some $7.8 trillion in 2010, increasing from $7.5 trillion in 2009.(4) However, that study noted that the proportion of global wealth held offshore slipped to 6.4 percent, down from 6.6 percent in 2009. This was attributed partly to growth in markets such as China, where the offshore wealth business is less common, as well as to stricter regulations in Europe and North America, which prompted outflows from offshore assets. While onshore wealth management is a major business, it attracts little public attention compared with offshore wealth management. Offshore banking is often associated in the public’s mind with money that has not been declared to tax authorities. It is often presumed by the public to be money belonging to criminals and dictators or other “politically exposed persons” (PEPs). This may have been one of the original motivations for depositing money in offshore bank account. Yet other legitimate reasons exist for holding funds offshore—assets that are fully declared to local tax authorities. Such assets might belong to an entrepreneur concerned about political stability and financial risk in his or her home country. Worries about capital controls, concerns about soaring inflation, or currency devaluations might all lead private clients to keep money in an offshore account. It is worth noting that, independent of why wealth might be held offshore, the distinction between “offshore” and “onshore” refers simply to where the money is booked. And due to mounting pressure from regulators, tax amnesties, and agreements hammered out between governments to force citizens to report foreign assets, it is becoming increasingly likely that money will be kept in such accounts only if it is declared.

In terms of offshore wealth, Switzerland is a global leader. The Boston Consulting Group has ranked it as the world’s largest offshore centre. In 2010, banks in the country managed an estimated $2.1 trillion in offshore client assets, representing 27 percent of all global offshore wealth held in accounts. This was followed by the UK, the Channel Islands, and Ireland, with a combined $1.9 trillion in offshore assets for a share of 24 percent.

The globalisation of wealth, together with changing demographics and increasing regulatory pressure, are encouraging a rise in nontraditional centres. This is reflected in the growing dominance of Singapore and Hong Kong as major financial hubs.

In recent years, Singapore’s role as a major private banking centre has grown tremendously. According to a study published by TCP The Consulting Partnership AG based in Zurich, the total volume of offshore assets managed in Singapore was in excess of $500 billion.(5) Singapore has long aspired to be “the Switzerland of Asia,” and in that sense it has become the uncontested leader, due to its modern regulatory environment, stable economy, a friendly and stable government, and an outstanding infrastructure.

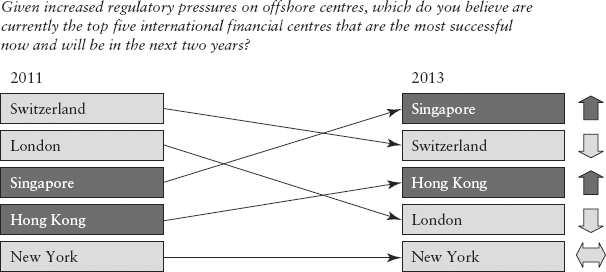

According to the Global Private Banking and Wealth Management Survey 2011 by PricewaterhouseCoopers International (PwC), Singapore could very well become the leading international wealth management centre worldwide by 2013, surpassing both Switzerland and London (see Figure 2.1).

FIGURE 2.1 The Center of Gravity for Wealth Management Is Shifting

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited. June 2011. “Anticipating a New Age in Wealth Management.” PwC Global Private Banking and Wealth Management Survey 2011

In addition, competition is intense. While Singapore and Hong Kong pose a genuine challenge to established centres and offer a wealth of opportunities, the costs to enter these markets are high and rising. This goes not only for hiring relationship managers (RMs), front office managers, and product specialists, but increasingly also for legal, compliance, and risk specialists as well, according to PwC.

Wealth Management in Transition

The 2008 financial crisis changed the banking industry. For one thing, clients have grown far less willing to put faith in markets, or, in many cases, the wealth management industry. Regulators meanwhile must reassess risks to financial institutions, especially those considered “too big to fail.” Banks need to pay strict attention to regulatory regimes that will play a major role in determining how business develops. New wealth being created in emerging markets increases the resources that must be devoted to legal and compliance knowhow, infrastructure, and technology of a bank along with acquiring local experience. At the same time, taxpayers in many countries who were already under scrutiny before the crisis now face mounting pressure to declare their assets held abroad to tax authorities. Governments are putting pressure on banks to divulge information about foreign clients.d The slowdown in industrialised economies in the wake of the financial crisis serves to highlight the importance of new financial centres in emerging markets, leading banks to look increasingly to these regions for business. In terms of banking, such growth provides a catalyst, leading the industry down new paths in terms of regions and clients.

THE FOUR KEY DRIVERS

As mentioned, the main forces shaping the private banking industry can be viewed in terms of four main drivers: markets, regulatory environment, clients, and competition. Examining each of these in turn will help provide a better understanding of where the greatest opportunities (and risks) lie and how a bank might best deploy its resources. The order in which these four are discussed in this chapter should not be taken as any indication of their relative importance.

Markets

Banking is a business whose cycles track fluctuations in financial markets. A private bank’s earnings are closely correlated with client assets, because a large proportion of the fees and resulting revenues are based on the assets under management. If the market drops significantly, reducing the value of client assets, this also might in some cases cause clients to be more concerned about the company managing their wealth, leading them to question the advice they have received. They are thus more prone to switch banks in periods of market distress than they would be when markets are steadily trending upward.

The problems that destroyed wealth in 2007–2008 were partly due to a failure within the financial system, making investors more prone to question the banking industry’s safety and soundness. In addition, an increase in new types of financial firms further complicated matters. Traditionally, money has circulated in the system between savers, borrowers, and banks. However, the rise of specialist non-bank financial intermediaries (“shadow banks”) over the years facilitated a complicated series of transactions outside normal channels, in which credits were created, sold, and funded by a number of different participants. Instruments designed to work well in liquid markets can come under pressure if one link in the chain breaks. As a worst-case scenario, the whole system can be compromised. Risks are increased by the staggering volumes at stake: credit “intermediated” by the US shadow banking system was close to $20 trillion on the eve of the financial crisis, nearly double the volume of credit provided by the traditional banking system, according to the US Federal Reserve.(6) Other estimates by the Financial Stability Board, an international body whose members include central banks of countries of the world’s major economies, found that on a global basis the figure pertaining to shadow banking is equal today to about $51 trillion, roughly the same as what it was at its peak before the financial crisis.(7) Not only did the system fail, but some supposedly “fail-safe” instruments did so as well. Little wonder that investors today have become skittish. The popularity of some higher-yielding investments was partly tied to a desire for higher returns during a period when bond yields were extremely low. In such markets, investors pay scant attention to risk.

Investors’ attitudes have become increasingly subject to extremes, ruled by emotions that are closely related to the market. However, one study has suggested that people who approach financial decision making unemotionally do better than those whose emotions are involved.(8) Clients should take a long-term view instead of making investment decisions based on “shorter-term” (one- to three-years) trends in markets. Investment objectives should be aligned with clients’ long-term goals and risk tolerance, factors that will be discussed in greater detail further on in this book.

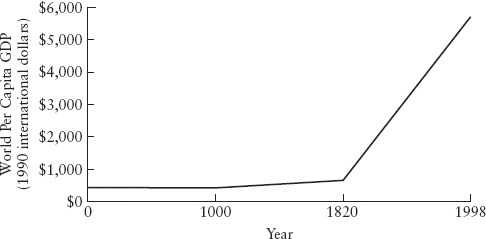

Taking a longer-term view in investing can make sense. Figure 2.2 illustrates that over the long run, world per capita GDP has tended to expand, generating added value, which should be reflected in efficient financial markets over the long term and result in an increase in global wealth. While there may be no exact correlation between the day-to-day performance in stock prices and the underlying growth in the economy, functioning financial markets provide liquidity and allow private investment, resulting in wealth appreciation.

FIGURE 2.2 A Long-Term View of Wealth Creation: World per Capita GDP

Source: Maddison, A. (2006), “The World Economy: Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective,” and “Volume 2: Historical Statistics.” Development Centre Studies, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264022621-en

Still, based on a short-term perspective, markets tend to present a picture of unnerving volatility, alternating between sharp upswings and severe drops. For investors exposed to these violent swings, their emotional response is often either to jump in when asset prices are peaking, due to fear of missing an opportunity, or to sell at lows, worrying that they will have to book large losses. In both cases, this could lead investors to take risks that do not match their long-term risk tolerance. It is thus up to the relationship manager to stay close to clients and guide them through the advisory and investment processes. This allows the clients to achieve long-term goals without succumbing either to panic by becoming overly bearish when markets fall or to excessive exuberance when markets rise.

Taking the long-term view is important, nowhere more than in investing. There is bound to be another bubble that likely will be followed by the next crash. It is hard to predict in terms of timing, but it’s a virtual certainty. No matter how much regulation is applied, risk will be part of the system. Volatility has increased partly due to technology, giving rise to phenomena like the “flash crash” in May 2010. With volatility a given, there is an even greater need to focus on longer-term goals.

Evolving Regulatory Landscape

Regulatory aspects are crucial. One area of concern relates to the level of capital banks need to safeguard against risks. Fears about the potential for the collapse of a major bank have led regulators to focus their attention on mitigating the chances that a financial institution might fail in the future, possibly jeopardising the entire system. The other key aspect is compliance. Governments in many developed nations, facing large budget deficits, have intensified their efforts to collect taxes on assets held by wealthy citizens abroad. These developments have major implications for private banks and the industry as a whole. How the issues are resolved will significantly affect the business.

Capital Adequacy

New rules to ensure that banks have enough capital are having an impact on the entire banking industry. Private banks are usually over-capitalised, in that their business focuses on managing private wealth assets rather than on more capital-intensive activities such as lending or trading. However, the discussions about risks have sensitised clients, particularly those of private banks, making them more aware of the importance of a sound balance sheet.

International rules governing the level of capital needed by individual banks were first drawn up by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in Basel, Switzerland during the 1980s. These were based on relatively simple formulas to safeguard against risks. The first Basel Accord’s familiar formula of capital equal to 8 percent of “risk-weighted” assets was lauded for its simplicity but was deemed insufficient, and Basel II ensued, followed by Basel III. This updated version is to be phased in starting in 2013. It is scheduled to come into full force by 2019. As part of these changes, the world’s largest banks will need to set aside extra capital. The so-called Swiss finish applied to the biggest Swiss banks is expected to call for these to hold more capital as well. It is not surprising that particular attention is being paid to such risks, given the enormous scale of Switzerland’s banking industry relative to the country’s size.

Tax Reporting and Disclosure

Sharing information on taxable assets with foreign authorities remains a central part of the discussions. For example, the European Union aims to have an automatic exchange of information system whereas separate bilateral agreements reached but not yet ratified between Switzerland and the UK, Austria and Germany are foreseeing an “equivalent” framework while still granting a certain level of privacy protection to the client. Outside of the European Union, the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has been active in seeking to increase pressure on foreign banks. The IRS established the Qualified Intermediary (QI) programme in 2000, followed by the US Congress’s adoption of the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) in 2010. Both measures aim to enlist foreign financial institutions to gain information on accounts held abroad. For further information on these subjects, refer to Chapter 4, “Forces Shaping the Regulatory Environment.”

Private banking as a major industry has not just shaped Switzerland, but to a degree it has determined how Switzerland is perceived outside the country. Due to its bank secrecy law, the country has come under pressure from national authorities, as well as international bodies such as the OECD. The Swiss government agreed in 2009 to adopt the OECD “Model Tax Convention,” which provides a basis for bilateral tax treaties among the organisation’s member countries. Article 26 of the OECD guidelines stipulates that member states must provide information with regard to “taxes of every kind and description.” Switzerland has negotiated or is in the process of finalising new double-taxation agreements with many countries based on these guidelines.

A Changing Client Profile

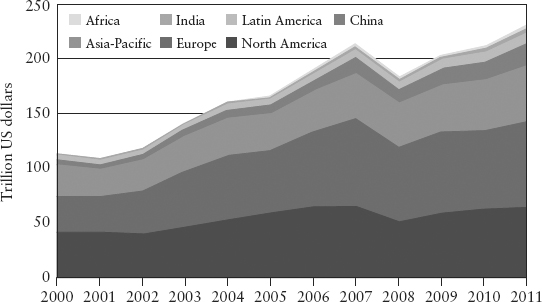

The pool of clients or potential clients, along with the wealth that can be managed for them, has expanded enormously in recent years. According to a study by Credit Suisse, the total wealth of all people in the world amounted to $231 trillion at the end of 2010 (see Figure 2.3). Total world wealth is expected to increase by 50 percent to $345 trillion by the end of 2016, based on the report published by the Credit Suisse Research Institute.(9)

FIGURE 2.3 Total Global Wealth Held by All Individuals in All Income Ranges (2000–2011)

Source: Credit Suisse Research Institute, Global Wealth Report 2011, October 2011

Given this rapid growth, banks must take into account the changing client profile and consider how this is affecting their business. A client of a private bank, often termed a “high-net-worth individual” (HNWI), typically has at least $1 million in assets. Based on this definition, the number of wealthy households is rising not only worldwide but especially in emerging markets, leading to what some commentators have referred to as a “tectonic shift” in global wealth distribution.(10)

The Rise of Emerging Market Wealth

Growth in emerging markets has outpaced that of developed countries, and wealth in these regions is being created as a result. China has overtaken Japan as the world’s second-largest economy. Other countries also are well placed to grow, including India with its enormous population of young people. Wealth has expanded in the economy of Russia and in the economies of countries in the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa, also supported by rising global demand for commodities. Moreover, emerging economies are also drawing more investments and further fueling wealth generation. In 2010, for the first time since records have been kept, developing and transitional economies absorbed more than half of global foreign direct investment flows, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).(11)

A changing mix of clients is influencing how these individuals approach management of their wealth. In the past, private banking clients typically were from established European and American families where wealth is passed on over generations. They tended to be more passive regarding their assets than an entrepreneur, for example, who has made money starting a business and prefers to be more actively involved in investment decisions. The service offering must be adjusted to meet the specific needs of new client groups. Many clients from developing economies are business owners who are still in the wealth-generation phase and need more integrated services that combine traditional wealth management with corporate finance or credit capabilities, (which a bank may provide either as an in-house offering or through co-operations with dedicated third-party providers). Private banks must also develop a deeper understanding of local investment opportunities to accommodate the growing demand for wealth to be invested domestically.

Generational Shift

As the baby boom generation retires, a new, younger group of clients has come to the fore. It is not uncommon for these clients to have gone to business school and to be acquainted with financial market theory. Clients tend to be getting younger; in 2010, 17 percent of the world’s HNWIs were 45 or younger, increasing from 13 percent two years previously, while in the Asia–Pacific region (excluding Japan), fully 41 percent are 45 or younger, based on an annual survey published by Capgemini Merrill Lynch.(12) These clients tend to be more demanding. Transfer of wealth from generation to generation also is making succession planning a key issue. The younger generation not only is getting involved earlier than might have been the case with their parents, but may also have a more sophisticated knowledge of financial markets. Therefore, it is vital to bond with young clients as early as possible.

Competition and Growth

Clients need solutions that are tailored to ensure that their money is managed in accordance with country-specific law and regulations and in a tax-efficient manner, according to how securities and other assets are treated in each relevant jurisdiction. By offering expertise in this area, banks can position themselves vis-à-vis competitors. It is not just products that make a difference; increasingly, it is the advisory role that sets them apart. For example, income and capital gains often are treated differently from one jurisdiction to another. The country or countries involved and the period over which securities are held, as well as the client’s specific situation and objectives all have significant implications on the suitability of an investment.

The financial market crisis raised worries about the safety of individual banks. Clients want reassurance that a bank is sound. As mentioned, after the financial crisis threatened to or in fact did topple some banks, clients wanted the assurance that their assets were not at risk. Clients now pay closer attention to key performance indicators including, for example, the loan-to-deposit ratio and risk-weighted capital (i.e., core or “tier 1” capital as spelled out by the Basel rules). Having a solid balance sheet today is an important positioning element vis-à-vis competitors. Clients today are paying closer attention to such metrics, and these can have a significant impact on how a bank might be viewed relative to its peers.

Tougher laws and increasing complexity of regulations have placed a bigger burden on banks’ administrative activities and have led to a greater portion of resources being spent on compliance. Increasing costs have put pressure on margins. This is driving consolidation within the industry. Rising costs are forcing banks to carefully choose the specific markets they target. Rather than entering multiple new markets, they must think about increasing economies of scale in specific markets. Growth brings benefits, but with it comes the danger of so-called reputational risk; as a bank expands, it might lose oversight of problems than can crop up in a division or region. Where competition is concerned, strong brand management and the ability to consistently deliver on the promises of the brand and the service offering are essential. Doing this will help to attract key talent, ensuring that the bank will be competitive in the future and can continue to position itself as a premium player in a market where only the best-positioned companies will succeed. Banks, especially private banks, need to keep risk functions centralised, and management plays a key role in safeguarding the bank’s reputation and brand. It is also in a bank’s interest to avoid dilution either to the brand or the service offering. Periods of expansion must be managed carefully.

CONCLUSION

Private banks face numerous challenges. Not adapting to the forces shaping the industry will only make the way ahead more difficult. Instead, banks must acknowledge changes and find ways to best structure their business, making choices that will affect the business well into the future. The four key drivers—markets, regulatory environment, clients, and competition—each have major implications for how the industry will develop. Those who understand and manage to master these forces and the related changes can look ahead with confidence. The same challenges that banks must confront also offer them the chance to succeed. The opportunities are there. Taking an active role in this business will prove to be rewarding, fascinating, and enormously interesting. Private banking does indeed have a great future.

NOTES

1. Swiss Bankers Association. http://www.swissbanking.org/en/home.htm.

2. University of St. Gallen. 2008. The Internationalisation of the Swiss Private Banking Industry.

3. Geiger, H. and Hürzeler, H. 2003. “The Transformation of the Swiss Private Banking Market.” Journal of Financial Transformation. Vol. 9.

4. The Boston Consulting Group. 2011. “Shaping a New Tomorrow: How to Capitalize on the Momentum of Change.” Global Wealth.

5. Hemmi, R., TCP The Consulting Partnership AG. “Market Opinion.” 17 November 2010.

6. Pozsar, Z., Adrian, T., Ashcraft, A., and Boesky, H. 2010. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, Staff Report No. 458, July.

7. Financial Stability Board. 2011. “Shadow Banking: Strengthening Oversight and Regulation.” Recommendations of the Financial Stability Board. 27 Oct 2011. Accessed Nov 2011. http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_111027a.pdf

8. Shiv, B., Loewenstein G., Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Damasio, A.R. Stanford Graduate School of Business. 2005. (Article first appeared in Psychological Science, 2005. Vol. 16, No. 6.) Accessed 30 June 2011. http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/news/research/finance_shiv_invesmtdecisions.shtml

9. Credit Suisse Research Institute. 2011. Global Wealth Report.

10. Booz & Co. 2010. “Private Banking. After the Perfect Storm.”

11. UNCTAD. 2011. “Global Investment Trends Monitor.” Global and Regional FDI Trends in 2010.

12. Capgemini Merrill Lynch Wealth Management. World Wealth Report, 2011.

aThe financial industry comprises both the banking sector (retail banking, wealth management, asset management, investment banking) and the insurance sector.

bOffshore clients are individuals who deposit their money in a bank outside of their home country. Onshore refers to those whose money is booked in their home country.

cThe Swiss Private Bankers Association lists the following 12 “unlimited liability” banks as members: Baumann & Cie, Bordier & Cie, E. Gutzwiller & Cie, Gonet & Cie, Landolt & Cie, La Roche & Co Banquiers, Lombard Odier & Cie, Mirabaud & Cie, Mourgue d’Algue & Cie, Pictet & Cie, Rahn & Bodmer Co., Reichmuth & Co.

dAccording to an OECD study on high-net-worth individuals published in 2008, the wealthiest taxpayers accounted for a significant portion of total income tax. In Germany, for example, the top 0.1 percent of taxpayers contributed about 8 percent of total income tax, and the top 5 percent of taxpayers about 40 percent. In the United States, the top 5 percent paid 60 percent of total income tax. The relative percentages in other OECD countries are likely to be of a similar magnitude. Significant resources are allocated to this segment, not because wealthy taxpayers are necessarily less compliant in their tax affairs but rather because of various factors, including the large amounts of tax at stake, the wealth and increasing number of high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), the complexity of their situation, their access to sophisticated tax products, and the potential impact of their noncompliance on the community, the OECD said.