Chapter 3

Finding the Right Organisation and Operational Strategy

A company that focuses on a single area of expertise is likely to be better at it than a company that divides its efforts among many different types of business. A standalone private bank is probably the best model in today’s business environment. A group that has private banking as just one focus among many others tends to be more complex; dealing with complexity takes time away from the most important activity in private banking—serving clients. It is possible to outsource some tasks to different providers, such as delivering specific types of products. At the same time, it is not possible to outsource all the main parts of the business. This is neither practical nor desirable.

To maintain quality, banks must be able to control all parts of the value chain, including the interfaces to external parties. These considerations form the basis for the discussion in this chapter.

ORGANISATIONAL FORMS AND TRENDS

The problems in the financial system that culminated in the collapse of some long-established banks and the near-collapse of many others in 2008 resulted in more than just monetary losses. For some banks, it marked the end of an era in which the prevailing mindset was often one of “bigger means better.” To its proponents, the benefits seemed obvious: take different business operations, such as investment banking, institutional asset management, private wealth management, and retail banking and combine them into one big, complex financial juggernaut that would produce “synergies.” Few companies that pursued this model have found as concise words to describe the opposite and ensuing problems that arose as financial markets unravelled during the bleakest weeks of the crisis. The losses these institutions sustained, not to mention the client defections that occurred, are evidence that there is no guaranteed safety in combining different businesses to create an enormous financial superpower. Even in good times, when too many dissimilar activities exist under one roof, inefficiencies result. In bad times, losses can escalate, as the “too big to fail” rescue of such institutions demonstrates. Government policymakers are rethinking the risks of having such behemoths in their home countries. Because wealth management generally provides a steady stream of revenue, often operating with a substantial capital cushion, it is a welcome addition to the larger group. For the private bank, however, the arrangement can turn out to be less than ideal. A private bank that is profitable in its own right can suffer collateral damage if another business within the group is hit with losses. And of course, private clients might rightly wonder if they are best served by a bank embedded in a larger, complex organisation.

Proponents of the “integrated” model argue that running many different activities within a single organisation produces benefits both for clients and the bank’s shareholders. Universal banks in the past have sought to convince investors that gaining exposure to many different markets and businesses would stabilise and enhance returns. Until the crisis in 2008, it was understood that an investment bank needed to belong, or at least compete with “bulge bracket” firms that rank among the global leaders in areas such as mergers and acquisitions, equity and debt issuance, syndicated loans, and the like. This type of business combined, for example, with retail banking, asset management—and wealth management—was supposed to offer stability and growth from interactions between the different activities. But having many irons in the fire was not always as beneficial as some believed. In theory, one part of the bank was supposed to provide a buffer to offset problems in another (very often with the private banking serving as the “stabiliser”). Instead, it might happen that problems in one area would tarnish the reputation of the sound businesses. The downside risks became clear in 2008, when the crisis affected some of the world’s biggest and best-known institutions, leading private clients in many cases to shun these banks or to withdraw wealth. Since then, financial companies have begun to reexamine the idea of whether it is sensible or even feasible to strive to cover a vast range of different businesses. Those favouring a clear separation, with a strong focus on just one area, can make a case—even more so perhaps after 2008—that being a provider of every service to nearly every client carries too many risks. In the end, a bank’s main consideration should be what business or businesses it wants to engage in. The considerations involved in this decision are the topic of this chapter.

The strategy a bank chooses must take into account client expectations, developments in financial markets, a new, more stringent regulatory environment, and the landscape for product and service offerings. For private banks specifically, when a strategy has been established, it is necessary to determine which structure is best suited to the core value proposition—namely serving clients’ needs and help them to achieve their goals. How is this to be achieved?

PRIVATE BANKING STRUCTURES

The current private banking landscape in Switzerland is the result of an evolution that began over two centuries ago. The oldest surviving Swiss private bank, Wegelin & Co. was established in 1741*. At the end of World War II, there were dozens of private banks in Switzerland whose business matched the formal definition of a private bank—one that is owned by partners, with at least one partner having unlimited liability for the bank’s commitments. Today many different types of banks are grouped under the general classification of “wealth manager” or “private bank,” while the number of those matching the narrower definition has dwindled to just 12 institutions as a result of mergers, sales, or adopting different business structures. Acquirers of private banks were often larger universal banks, which purchased these with the aim of expanding in a lucrative, high-margin business. In addition, banks better known for their retail offerings also tried to increase their wealth management activities by appealing to wealthy clients and those in the upper tier of the growing affluent sector. Technology also has enabled wealthy individuals, typically those with investable assets of at least $100 million or more, to set up their own family offices.

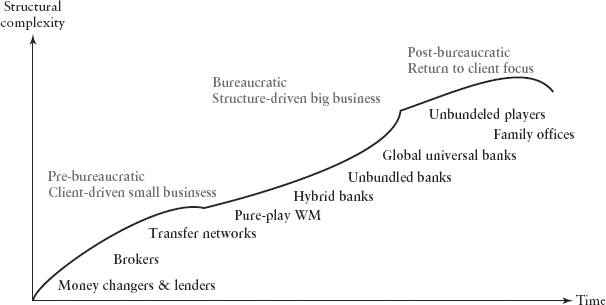

For banking as a whole, Figure 3.1 represents how the model has evolved: “pre-bureaucratic” describes a rather simple, less specialised type of operation. Moneychangers, brokers, and money transfer networks are considered pre-bureaucratic. Organisations in this category tend to be small enough to be run in a simple, straightforward manner. The founder is usually involved in the everyday details, including most, if not all significant decisions. These tend to have a flat hierarchy and lack standardised processes. They might be small operations run with just a few people. Such types of businesses have been around since antiquity and some of them still survive today.

“Bureaucratic” organisations offer a greater number of products and services. The structure clearly starts to differentiate between various activities within the business. Standard routines governing processes are common. Leadership and reporting structures, discussed in Chapter 11, “Defining and Growing Leadership and Culture,” are more developed. There is a need to manage increasingly large numbers of people, products, and services. This approach can generate efficiencies by organising people into groups dedicated to specific tasks and goals. If care is not taken, however, it can give rise to silo mentalities and intensify friction arising from internal politics, reducing efficiency. Organisational inertia may ensue. This type of organisation is the prevailing one in banks. But with the advent of increasingly bigger banks, incorporating many different activities, the business model has grown increasingly complex. The financial crisis exposed the weaknesses of this structure, where complexity can overwhelm even skilled managers. When a structure becomes too entrenched, hierarchies too codified, and rules too complicated, inefficiencies arise. Thus, a highly bureaucratic organisation defeats the purpose for which it was designed—to increase efficiency and reduce costs. In the interim, some banks have started to simplify their organisations to focus on fewer areas, concentrating instead on niches and/or core competencies.

Flatter hierarchies and more direct decision making are typical of the “post-bureaucratic” organisation, characterised by its focus on a core activity. In such a company, visionaries recognise opportunities based on new trends and technologies. This leads to more flexible and client-centred organisations. A post-bureaucratic structure can be seen as an antidote to the top-heavy structures that impede internal change and make it difficult to focus on the core business.

Devoting more attention to core competencies is understandable, especially after the problems encountered during the 2008 financial crisis. Not only were some businesses too complex and inflexible, they needed capital. In the interim, some banks got bailouts from public authorities. Many that experienced problems were also forced to sell non-core businesses, including wealth management businesses. This trend created a window of opportunity for private banks to buy client assets at reasonable prices.

Organisational Structures

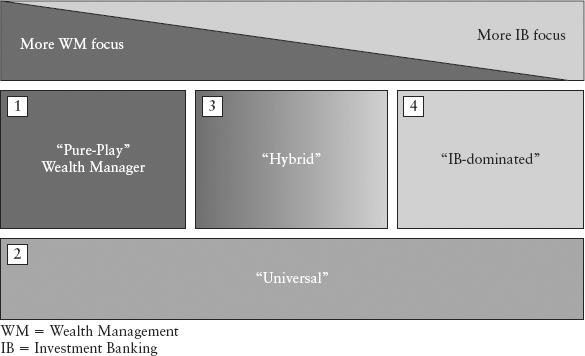

Management consultancy Oliver Wyman identified the four most common banking models that incorporate wealth management within their overall structure.(1) As shown in Figure 3.2, pure-play wealth managers are those that focus on a single business: wealth management. Banks of this type include private banks such as Julius Baer, Sarasin, and EFG International. Universal banks, the second category, are active in many different businesses. Some examples include BNP Paribas, HSBC, and RBS. Banks classed as hybrids make up the third category. Hybrid banks are similar to universal banks but lack their extensive international retail networks. UBS, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, and Merrill Lynch (which was sold to Bank of America in 2008) belong to this category. The final group is made up of institutions dominated by investment banking. Two such firms, Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, failed in 2008. The other two remaining major US investment banks, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, changed their status to bank holding companies during the crisis.

FIGURE 3.2 Organisational Models of Wealth Managers

Source: Oliver Wyman, “The Future of Private Banking: A Wealth of Opportunity?” 2008

Another way to look at the different operational models is to focus solely on how the wealth management business is positioned within the larger group. It might be that the private bank or wealth management unit operates independently, sharing only the brand. Or the wealth management unit could be part of a retail bank or be integrated into a corporate or investment bank alongside the corporate finance and asset management units. It might also be a unit run alongside, but distinctly separate from the retail bank.

Apart from internal factors influencing the changes shaping the banking industry, external factors including increased regulation are affecting it from the outside. Banks are subject to increasing scrutiny. Pressure is being brought to bear, especially on the banks deemed “too big to fail.” Because they possess assets that might be greater than their home country’s annual GDP, the failure of one of these could severely strain the financial resources of an entire nation. Based on the different types of structures just discussed, the pure-play private bank has some advantages in this regard over institutions with multiple businesses due to its clear focus.

Universal vs. Pure-Play?

The study by Oliver Wyman also analysed the synergies arising from combining businesses. Using a “hybrid” organisation as a model, it looked specifically at four particular areas where benefits are presumed to exist, to weigh how much value is derived from joining different activities. Are there real benefits to having a variety of different operations in one large financial group? If these exist and can be measured, which parts of the operation gain from having a combination of different activities united in a single organisation? The following points shed some light on the assumption behind combining businesses and benefits for the individual units or activities:

Taking into account these points, only the fourth—client referrals—offers obvious benefits to the wealth management business. To sum up, the study found that the investment banks in this type of operation derived on average an estimated 7 percent of revenues from synergies, while retail banking showed no gains. Asset management benefited the most, claiming fully 12 percent of revenue from synergies gained by being part of a combined group. Wealth management gained only 1 percent. The findings were based on data gathered in 2006. In the wake of the financial crisis, the figures might be skewed even more decisively in favour of the other businesses relative to private banking.

Risks to the wealth management business can increase when it is brought into the same organisation alongside other activities such as investment banking. Wealth managers, due to the nature of their business, usually hold well in excess of the minimum required capital. As banking groups can leverage business based to some degree on client deposits, the wealth management business may even, as noted in the first point, provide the group’s other businesses with a means to take on more risk. And if the group suffers major problems in another area of the business, the wealth management business could experience outflows of client money, which would mean that assets on the group balance sheet also need to be reduced. Thus, in this sense the wealth management business truly might serve as a stabiliser—but not in the manner intended.

The Problem of Referrals Management

For private banks, the main incentive to be part of a group that includes other businesses can be found in the potential for client referrals. However, based on a report by the Boston Consulting Group,(2) many universal banks struggle when trying to implement effective systems for gathering leads. To make referrals work, all parties must agree that there is a value in having a unified entity. Setting up a referral system is not so easy. It requires clear rules. Very often, banks fail to keep records on referrals, and the managers also might neglect to offer benefits within the company that are needed to encourage them. At the heart of a working referral system, there needs to be commitment from management, incentives, trust, and a system to ensure that clients are getting the service and the continuity they need.

Very few banks actually achieve an effective referral system. There may be different reasons for this. One is that employees might not want to entrust their clients to another part of the bank and are reluctant to risk jeopardising a relationship with a good customer. In practice, it’s not so easy to give up clients, and not just in private banking. Retail bank managers also tend to be unwilling to voluntarily refer their wealthiest clients to the private bank, fearing inadequate compensation for lost business. Beyond that, existing client relationships usually are hard to change: an entrepreneur, for example, may have worked for decades with his or her branch manager or corporate finance advisor.

It is clear that when wealth management is brought into a group with other business units, the main benefits in most cases go not to the wealth management unit but rather to the other businesses. Yet in a pure-play wealth management business, there may also be tensions and imbalances arising due to competing aims among the company’s core activities. Besides looking at how wealth management may be integrated within a larger group, it is important to consider the organisation of the wealth management unit as a separate entity that often must take into account different, sometimes even competing parts of the business. This is discussed in greater detail in the following section.

DESIGNING THE ORGANISATION

Chapter 1, “A Framework for Excellence in Private Banking,” introduces a model that can be implemented to manage a private bank, serving as a guide to the process of turning a proposition for the future into a concrete strategy, an action plan, and a system with the necessary controls. The changing business environment has forced private banks to reexamine where and how they want to compete. In looking at the best ways to organise people, activities, and resources in order to implement the strategy, a three-pillar model representing the main areas of operation within a private bank can be envisaged. It is also important to consider why large corporations have been formed in the past and whether the same forces still work in their favour today.

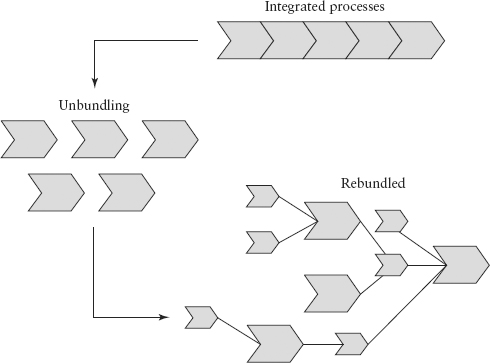

A key aspect is how much it costs to provide goods and services in-house versus the cost of getting the same goods and services externally. In both cases, assuming the market price for these goods and services is the same, the decision comes down to the costs associated with acquiring the same goods or services. Once such costs become higher than would be the case to source externally, internal production no longer makes sense. When this tipping point is reached, companies, including banks, may benefit from unbundling—separating, outsourcing, and/or divesting certain non-core activities as is discussed in the final section of this chapter.

Bundling and Unbundling

Nobel Prize–winning economist Ronald Coase first introduced the concept of transaction costs in a 1937 article, “The Nature of the Firm.”(3) Asking why companies exist, he determined that it is profitable to establish a firm when it can reduce the costs involved in transactions that arise during production and exchange in a way that individuals cannot. As long as costs associated with coordinating the exchange of goods and services are lower within the company than they would be if the goods are sourced externally, it makes sense to keep the production and services in-house. For example, in the early years of the automotive industry, automakers produced many more parts in-house. But a great deal of time and energy was expended to produce these items. There were substantial costs involved in administration of the production, for example. If it were less costly, a vertical production system starting with making the steel to produce parts, downstream to manufacturing the upholstery, would make sense. But overseeing such a production process would require a large number of internal resources, ranging from ordering materials to legal resources that are needed where patents and regulations are involved. The model of an all-inclusive, vertically-integrated company where most of the value chain is kept internal thus tended to give way to outsourcing those aspects of production, where it makes sense to do so. With a modern car today having about 30,000 parts, it would be impractical in the extreme to try to produce everything in-house. The auto industry has thus “unbundled,” encouraging external companies to specialise in specific areas of manufacture. Figure 3.3 depicts this process of unbundling.

FIGURE 3.3 Unbundling and Rebundling of a Value Chain: How Businesses with a Variety of Activities Might Reform to Concentrate on Their Special Areas of Expertise

Sources: Manuel Keller, “Virtual Private Banking: Vision or Illusion.“ Zurich: Swiss Banking School, 2000

Thinking in terms of “unbundling” can give an impetus to other industries. The car radio is an example. A radio supplied with the car increased the price of the car by so much that it proved impractical. Already in 1930, American Paul Galvin introduced one of the first commercially successful radios for cars. These were sold under the brand name “Motorola,” reflecting the radio’s mobility. His entire company later changed its name to the one associated with this early, successful product. Motorola became a recognized leader in the audio industry.(4)

The Three-Pillar Approach in Corporations

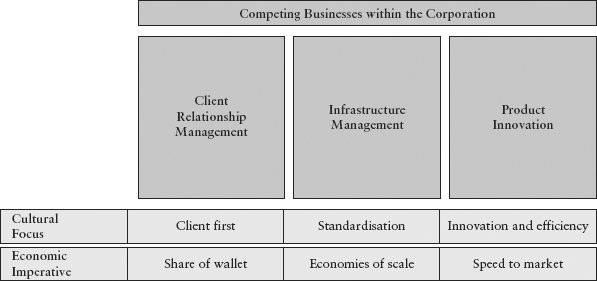

In 1999 management consultants John Hagel III and Marc Singer, in an article published in the Harvard Business Review, explored the nature of costs arising from core functions within an organisation.(5) They described the three main areas central to most companies’ activities: customer relations, products (including product innovation), and corporate infrastructure, represented as three pillars (Figure 3.4). The friction that arises between these creates a drag in terms of lost efficiency and higher costs. Traditionally, these “interaction” costs have been regarded as an inevitable part of doing business, and most companies strive to make these various activities work together as efficiently as possible. There are limits in terms of what can be achieved by streamlining core processes, however. Technology meanwhile is challenging this model by enabling smaller, more specialised companies to take over certain tasks. As a result, the basic assumptions about corporate organisations need to be reexamined. The rise of nimble specialists focused on just one core process—for example, product innovation—shows that while size, reputation, and integration were advantages enjoyed by big companies in the past, today these same large corporations face competition from all types of agile niche players. At the same time, the core processes within these big companies often compete with each other, meaning that none are as efficient as they would be if they existed separately. Hagel and Singer argued that what most managers have considered to be the three “core processes” are in truth three separate and distinct businesses. Each has goals that are in some ways incompatible with the other two. To work together, each must compromise, sacrificing some of its efficiency.

FIGURE 3.4 Competing Businesses within the Corporation

Source: “Unbundling the Corporation” by John Hagel III and Marc Singer. Harvard Business Review, March/April 1999

Each of these three business areas is driven by fundamentally opposing economic, cultural, and competitive aims. For example, customer relationship management (CRM) strives to give each client the best possible experience and service. As the name implies, the emphasis is on the relationship, so one of its goals is to offer as many different products and services as possible. It aims to build ties with new clients while satisfying existing ones. By contrast, infrastructure management is capital-intensive and therefore most profitable when economies of scale are pursued to spread the fixed costs over many different clients. Standardised solutions are its ideal. It is most cost-effective when functioning as an impersonal, standardised provider. The third core activity, product innovation, has yet another aim. It focuses more on employees than on customers, so its efforts are directed mainly towards attracting talented staff to create new products. While all three of these activities often coexist within a single company, some friction is inevitable. According to Hagel and Singer, compromises thus are necessary when all three processes exist side by side.

The Three-Pillar Approach Applied to Private Banking

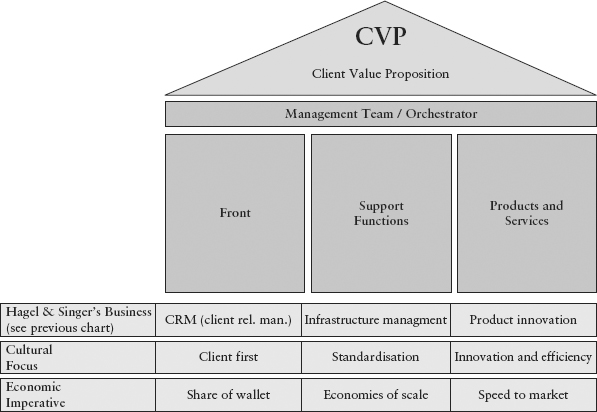

Figure 3.5 represents the three main functions needed to run a private bank. The first pillar, referred to here as “front,” comprises all of the client-facing activities and services, meaning those parts of the operation that come into direct contact with clients. Support functions build the basis to enable the front to serve the clients. Usually the support functions cover all employees who are part of the mid- and back-office functions. The third key area develops and provides products and services to relationship managers (RMs) and clients.

FIGURE 3.5 The Three Pillars Applied to Private Banking

Source: Author, inspired by “Unbundling the Corporation” by John Hagel III and Marc Singer. Harvard Business Review, March/April 1999

Similar to Figure 3.4, the three pillars represent the attributes and characteristics of each of these main activities. As in other corporations, when all three are included in a company, each has to some extent goals that do not align with the priorities of the other two. This creates tension as individual areas are forced to make compromises and concessions to accommodate the others. The management team’s job becomes one of coordinating or orchestrating so as to deliver value to the client. To accomplish this, management must attempt to strike a balance to minimise tensions among the separate areas of function. If management succeeds in elegantly orchestrating the cooperation between the activities, clients will respond positively. Satisfied clients will increase the amount of total assets entrusted to the bank: they will stay with the bank longer and even give referrals.

Each of the three pillars needs to be organised in a particular way to ensure that the main goals are met.

Pillar 1: The Front

The operations referred to as the “front” functions encompass all the activities of the business that come into direct contact with the client. This is where the client relationship is established and maintained.

Private banking is a business that depends on networking and is focused on people. The relationship managers are the bank’s key assets, and relationship managers’ personal networks, in turn, are their greatest assets. A relationship manager needs to have a certain basic level of banking and financial expertise, and as the regulatory and product environment becomes increasingly complex, relationship managers’ networks of expert advisors also gain in importance. Relationship managers thus are becoming orchestrators of an array of services. They needn’t have the answer to every question, but they ought to know where to go to get it. The front office organisation needs to reflect this. Relationship mangers should be organised into teams. The bond between the client and the individual relationship manager, which lies at the heart of the client value proposition, needs to be expanded in a discreet manner to include other team members, which also helps to anchor client loyalty to the brand (see Chapter 7, “Why Brand Matters” and Chapter 9, “Understanding Service Excellence.”)

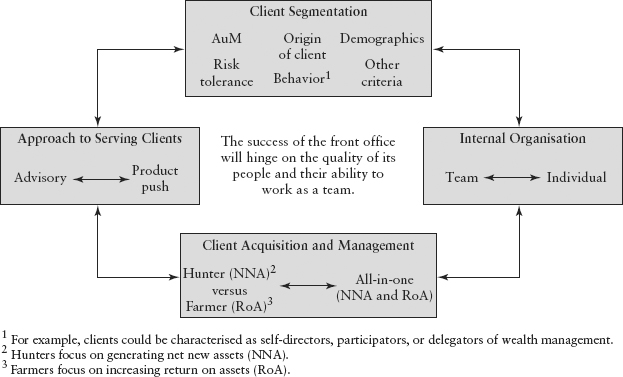

The ideal organisation for a front office in private banking will vary, based on the number of clients, the client segments targeted, the approach used to serve clients. and the types of relationship managers employed. According to Boston Consulting Group, there are different types of relationship managers, which it refers to as either “hunters” or “farmers.”(6) As shown in Figure 3.6, relationship managers are focused on acquiring and managing clients. Those whose main aim is to increase net new money (NNM) might be referred to as “hunters.” Those focussed on increasing the return on assets (ROA) might be better described as “farmers.” According to the study, the more experienced a relationship manager becomes, the more likely it is that he or she will evolve from being a hunter to a farmer, the latter often a function of age, experience, and increasing client load.

FIGURE 3.6 Factors Affecting the Organisation of the Front Office

Source: Global Wealth 2008: A Wealth of Opportunities in Turbulent Times © 2008, The Boston Consulting Group

However, this depends very much on the strategy and incentives of the individual bank. A bank with a growth strategy will encourage relationship managers to increase net new money (NNM), having as its main focus a hunter strategy. A well-functioning team needs a mixture of both, however, including younger and older relationship managers. Based on their different ages, levels of experience. and opportunities to tap networks, different relationship managers might pursue a mixture of strategies. The team also needs to have access to specialists. In order to face the challenges of the increasing competition for relationship managers and the need to develop leadership, an environment should be able to develop relationship managers with both “soft” and “hard” skills through coaching and mentoring and by supplying experts able to offer advice. With that in mind, the front office could be organised along the lines of the following format:

- A team head (coach, mentor, leader, role model)

- Four to eight relationship managers (mixture of hunters and farmers)

- One or two assistants

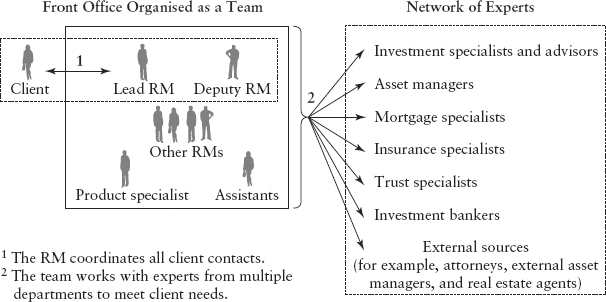

- Product specialists able to provide an interface to a network of experts

Historically, the main value proposition of private banking has been to offer the benefits secured by a trusted client advisor. As much as banks seek to emphasise the team approach, clients still appreciate the continuity, stability, and assurance provided by having a primary relationship manager (RM). However, markets have grown less predictable and products more complex. This has led to a need for a heightened level of expert advice that typically can no longer be satisfied by a single individual. Perhaps the solution to this dilemma lies in the “front-centred web” model. In this approach, a relationship manager or a team of relationship managers may serve as an interface between the client on one side and a network of experts on the other.

Today’s high-net-worth client needs access to a variety of different experts, including specialists in the areas of asset allocation, fund selection, estate and tax planning, currency hedging, and succession planning, to name just a few. Depending on the size of the client base and the economics involved, these experts may either be in-house or vetted specialists from outside the bank. Product specialists are one example of in-house experts who can be called on to brief clients regarding specific topics that are highly complex or might address and analyse rapidly unfolding events in financial markets. Product specialists can be assigned to a regional team but can also serve other teams through a type of matrix organisation that may also allocate them to the unit that provides products and services. One example might be a product specialist working in the product and service department of a Swiss private bank in Singapore, who could be the ideal expert to brief a Swiss-based client on opportunities in emerging Asian markets.

Figure 3.7 provides an overview of how a front-centred web might be organised to deliver value to clients.

FIGURE 3.7 The Front-Centred Web

Source: Global Wealth 2008: A Wealth of Opportunities in Turbulent Times © 2008, The Boston Consulting Group

Up to this point, at least in theory, the whole organisation could be operated without any physical premises as a sort of “virtual value web” where team members work out of home offices using the latest communication tools to coordinate their activities. However, this utopian vision will probably break down when the first client asks where he or she can go to make a deposit. For the foreseeable future, clients will still place a great deal of confidence in the existence of real, physical buildings, be it the “bricks and mortar” premises in prestigious locations in cities, or offices in places with a high traffic of wealthy individuals. In other words, to engage in wealth management activities, it is still necessary to have a high-visibility branch network infrastructure that is part of the support function pillar. As discussed in Chapter 7, “Why Brand Matters,” and Chapter 8, “Delivering a Superior Client Experience,” it is important to provide a premium level of client experience, considering all instances in which the client could encounter the bank, from advertising to its appearance on the street and to the reception area or individual meeting rooms. These facilities need to be managed as part of the responsibility of the support pillar shown in Figure 3.4. Alternatively, such tasks may be outsourced.

Pillar 2: Support Functions

The support functions are required to make everything else happen in the organisation. They work best when allowed to take advantage of economies of scale and standardisation.

The front office could not operate effectively without the assurance that flawless support provides. Besides proprietary know-how and organisational expertise, the support functions set a private bank apart from an independent financial advisor or a family office or broker. How best to organise these? Based on the approach outlined by Hagel and Singer, support functions rely on principles of cost-effectiveness and efficiency delivered by economies of scale and standardisation. If a bank wished to establish a purely digital booking platform, the more clients persuaded to use it, the greater would be the cost savings per transaction. The complete opposite is the case for the front, where every added client leads to increased costs. It takes time and many other investments to satisfy the new client’s needs and to deliver real value.

The bank’s legal and compliance departments are included in support operations. The complexity of legislation and associated costs is increasing. Here, too, the challenges faced are best met by taking advantage of economies of scale—meaning an increasing number of clients must be acquired to spread the costs associated with legal issue and compliance. If these operations are maintained at best cost, and economies of scale are not an option, the bank would have to try to save through standardising products and services—reducing the number of markets and segments in which it is active or by offering fewer products and services. In addition, public relations and human resources are part of the support functions. The greater the number of individual tasks that are similar, the higher the savings will be.

A private bank needs therefore to decide if it has a large enough client base to carry the costs of these support functions in each market where it wants to be active. Or does it need to find a partner, to merge or outsource one or more of these functions? Beyond that, there is the question of what, if anything, the bank could or should standardise if it wants to save costs. Should it focus on fewer markets or a smaller number of client segments? Should it reduce its product and services palette? How far can it go down this path without compromising value in terms of solutions tailored to each individual client?

These support functions need to be guaranteed in any private bank: legal and compliance; risk management and controlling; finance; facilities management (for both the physical branches and office network); human resources; IT and operations including execution and custody; and marketing and communications.

Pillar 3: Products and Services

This business creates and provides financial products and services.

The final section of Chapter 6, “Beyond Products—Offering Tailored Solutions,” addresses the questions related to the types of products and services that a bank should offer. This chapter looks at how products and services are approached at the organisational level. When thought of in terms of a standalone business, this pillar focuses on innovation, process efficiency, and speed, expressed as time to market. Product designers must be able to exploit opportunities as they arise, and they must do it faster than the competition, allowing these products to capture first-mover advantages such as premium pricing and market share. The task for the private bank then becomes one of choosing which products and which services need to be produced in-house and which might be externally sourced. And, no matter whether they are sourced externally or provided in-house, there is also an organisational aspect: for external products and services, the selection needs to be organised, while in-house products also require their own organisation.

One way to address the various issues that arise in the area of products and services is through open architecture, meaning platforms to provide both in-house and externally sourced products, presented without bias or advantage for either internal or external offerings. Technology, which has significantly reduced transaction costs, has enabled such systems to be devised and operated, while open architecture extends this flexibility to financial products and particularly to funds.

CONCLUSION

Historian and economist Alfred Chandler, in a seminal study of four American conglomerates published in 1962, found that these shared a common trait in that they were based on a “decentralised” organisational model.(7) The organisational model, he postulated, works best when the company’s structure is brought into alignment with the strategy. If it is not, the existing structure may hold back changes in strategy, including those necessary to the company’s long-term growth. Chandler’s theories are often summed up as “structure follows strategy.” If that is the case, for a company to be successful, it must first determine its strategy before deploying a particular structure.

This means that an organisation’s primary focus has to be defined at the outset. Once this has been achieved, it can then focus on the structure that best suits its aims and, if necessary, it can unbundle those businesses that are not aligned with its focus.

For banks, the financial crisis underscored the need to rethink existing strategies to position for a future in which stricter regulations and greater risk control play a larger role. If structure truly follows strategy, banks, too, must rethink their traditional structures in order to align them with the strategies that they need in today’s wealth management market.

Some experts believe that in the future, banks will concentrate solely on the client advisory process and leave investment management, legal structuring, research, and the like entirely to external providers. This might be cost-efficient, but banks need to have a solid proprietary offering in the core areas that demonstrates capabilities and guarantees certain standards of security and service. For example, no matter whether the bank has its own in-house funds or not, it needs to have a fund selection capability and an actual team providing this service. The goal is to offer the client and the relationship manager a short list of recommended funds that are all good choices, depending on the predetermined risk level and to ensure ongoing continuous monitoring of these funds.

The concept of “structure follows strategy and the organisational form” will be essential for a successful implementation. It is impossible to manage what one can’t measure. Similarly, it is not possible to add value in sales and delivery if a bank doesn’t sufficiently understand those functions that it outsources.

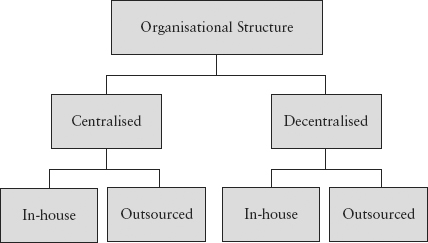

Assuming that the bank is not being built from scratch, one must look at every aspect of the business model, asking how every part can be refined to contribute to the delivery of the client value proposition. It is therefore necessary to look in detail at the operating model to see how the structure and processes can be improved. This contributes to the efficiency of operations to the benefit of the client while providing a reasonable return for the bank. Figure 3.8 outlines the main question that will determine how each process or function is to be approached. It shows the key decisions that need to be made to turn the operational model into an organisational structure. Which functions should be in-house or outsourced? What is the best organisational structure? Should the company be organised centrally or decentralised? Here is one example: a bank decides to outsource its payroll activities but still needs to decide whether there will be one global partner, such as an international accounting firm, or whether each country should subcontract the work locally. Another example would be, assuming a bank chooses to have fund selection in-house, it must decide whether it is better to have one team based at its headquarters doing the job for the global operation or whether it is better served by regional teams that can take into consideration geographic preferences.

The financial crisis followed an extended period of rapid growth when many wealth managers pursued revenue gains at all costs. With their asset bases now diminished and revenues less certain, private banks face significant pressure to go over their operating models in detail, seeking ways to get better control over their businesses, support functions, and processes. This is necessary in order to cut costs and improve margins, while providing better service to clients.

Choosing the optimal organisational design can be a significant help in streamlining operations and keeping costs at reasonable levels. This chapter opened with the question, What is the ideal organisational form? In the end, there is no single answer. It will depend on each bank’s strategy, positioning vis-à-vis clients, and the market environment in which the bank operates. In the near future, it is quite likely that wealth management units of universal banks might try to leverage their brands, aiming to exploit economies of scale by reaching out to the affluent sector. Meanwhile, pure-play wealth managers are likely to pursue open architecture models, creating a distance between themselves and asset managers on the one hand and investment banks on the other, to focus on their main activities of client-focussed wealth preservation and offering independent advice. To add the most value, private banks invariably will need to focus their efforts on the front pillar—the main client-focused area of their business—and the network supporting it.

It will not be possible for a private bank to focus entirely on the front pillar, however, while outsourcing all support functions, and product and service activities. Private banks must take into account the changing nature of the business, making it difficult to establish service-level agreements with third parties. The regulatory environment is also changing, and in many cases, this creates new demands on private banks. Legal and compliance operations within the bank thus become even more important, serving a role that requires clear processes. Private banks will need to use all the advantages of value webs—interactive and fluid organisations that can access different experts to provide support when needed.

Unbundling is about focusing on core knowledge and skills. Open architecture serves to offer competitors’ products on an equal footing as the bank’s own. In practice, the barriers to both open architecture and unbundling in private banking are significant but not insurmountable. Admittedly, technology has reduced the cost of getting the product, of getting information about products, and communicating with suppliers. But the private banking value proposition has always been about customised solutions for every client. Maintaining credibility and control of key parts of the business could be compromised if a bank relies too much on outsourcing. Core processes—not just the front, but also important knowledge and skills—cannot be fully outsourced.

One way to address this is to unbundle different parts of the business—that is, the different parts of the value chain representing all the steps necessary to achieve a desired result. Other industries already have looked to this model and are in the process of unbundling their businesses. In wealth management, however, few players thus far have had the courage to pursue this aim. The need for client confidentiality and the ability to provide all the necessary services while maintaining security all argue for keeping all processes under one roof. A perceived need to directly control all aspects of the business leaves most banks with the idea that they have to run all three core processes within the three main organisational pillars in-house, despite the inefficiencies. Even here, many support functions can be and have been outsourced. An increasing number of banks have opened up product innovation to the market by implementing an open architecture approach. For example, Credit Suisse offers third-party products via its Fund Lab platform. It sold a significant portion of the company’s asset management operations to Aberdeen, a leading asset management specialist. Julius Baer split off its asset management into a separate unit. The remaining bank is one of the largest pure-play wealth managers in Switzerland.

The following principle should apply: do not outsource something that is not working internally. If the bank cannot get the process right, how can it define the interfaces and the agreements to avoid difficulties when these same functions are outsourced? Having first-hand experience is vital, too, for pricing and quality control. Outsourcing may shift the work and responsibility to a third party for providing the product or service. But a significant amount of management attention is required. An outsourcing arrangement needs constant monitoring and management of the relationship to ensure that the bank’s brand and reputation are not damaged by substandard products or inadequate delivered products and services by external partners.

In the end, effective implementation and execution is more important than having either the perfect strategy or model. Chapter 12, “Measuring and Managing Performance,” addresses this topic.

In private banking specifically, unbundling makes some sense. The main aim of the RM is to focus on separate, individual clients, with the goal of providing ways to generate long-term wealth preservation. Time-honoured traditions of service and individualised offerings, exclusive client meeting rooms, and a deliberately low-key and highly personalised approach work best. Not only would the relationship managers gain from being freed of offering internal products when clients prefer external ones. In addition, an unbundled products division would no longer be held hostage to in-house relationship managers’ demands and could extend its offerings more effectively to a broader audience. The infrastructure business, too, could pursue its goal of achieving economies of scale by offering its booking platform to multiple parties.

NOTES

1. Oliver Wyman. 2008. “The Future of Private Banking: A Wealth of Opportunity?”

2. Boston Consulting Group. 2008. “A Wealth of Opportunities in Turbulent Times. Global Wealth.

3. Coase, R. 1937. “The Nature of the Firm.” Economica 4(16).

4. History of the Motorola Brand and Logo. Motorola corporate website. Accessed 20 May 2012. http://www.motorolasolutions.com/US-EN/About/Company+Overview/History/Explore+Motorola+Heritage/Music+in+Motion

5. Hagel III, J, and Singer, M. 1999. “Unbundling the Corporation.” Harvard Business Review, March/April 1999.

6. See note 2 above.

7. Chandler, Alfred D., Jr. 1962/1998, Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

*All except the US business of Bank Wegelin & Co. was acquired by Raiffeisenbank in January 2012.