Chapter 11

Defining and Growing Leadership and Culture

In private banking, it is important to demonstrate that the institution can challenge the accepted wisdom and provide new and creative solutions. A leader may be defined by some particular event that requires the ability to deal with something where the perimeters are different, difficult, or not clearly defined, such as opening a new business. It is in fact much simpler and perhaps more exciting to build up something from scratch in a growth market. In an established business, the task of leading change is no less difficult. Taking time to communicate is always a high priority, to people both inside the firm and on the outside. Establishing a sense of purpose is also important in any company. Beyond that, it is necessary to give people tasks whose demands exceed what they personally believe they can accomplish. My biggest satisfaction is hearing someone say, “I never thought it was going to be possible, but we made it.” If you really want something, you can make it happen. During my career, I have seen people rise to the occasion. How the concept of leadership has evolved and what makes a good leader are the main topics addressed in this chapter.

WHAT MAKES A LEADER?

Leadership is the focus of countless books, seminars, and conferences.* As often as it is discussed, however, what precisely “leadership” is, let alone how to encourage its development, is subject to much debate. Ideas about what makes a good leader can change. When people are young, their earliest leadership models are often remote figures, such as sports stars or fictional heroes. As they get older, they begin to question what qualities really make a good leader. Leaders who seemed remarkable a generation or two ago might be viewed through the lens of history as somewhat less impressive. In business, some leaders lauded by their contemporaries may appear to us today as simply opportunists who acted out of self-interest and with disregard for the rights of others. Even the best leaders who fail to secure the support of followers are apt to struggle to maintain their mandates.

Leaders need integrity to stand the test of time. People who believe they know what attributes a leader must possess (persistence, self-confidence, tolerance, task knowledge, etc.) cannot guarantee that someone possessing all these qualities will succeed, any more than they can predict that someone who apparently lacks them will fail as a leader. Crises can bring out leadership qualities that individuals did not know they possessed. The idea that everyone potentially has the qualities of leadership makes the subject relevant and worth discussing. Being able to spot the leadership qualities in others and encouraging these can also define a true “leader.”

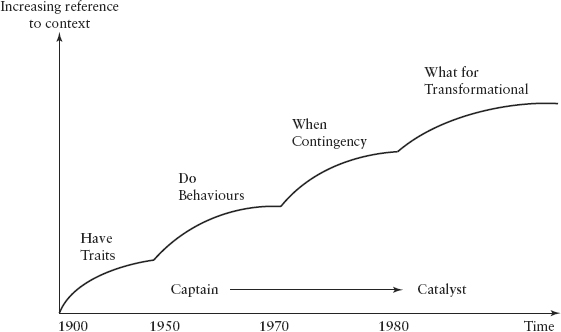

In terms of business leaders, a great deal has changed over the years, including how leadership is perceived and studied. As shown in Figure 11.1, over the past 80 years or so there have been four principal leadership theories.(1) Early studies focused on traits of leaders. Once research began into what makes a leader, at first it seemed obvious to analyse certain traits considered necessary to lead. Such theories postulate that leaders possess certain outstanding qualities that others lack. Heroic leaders are men and women, so the thinking went, who had characteristics that set them apart from others.

One danger with this theory is that leaders who believe they possess these qualities may infer that they are “destined” to lead, perhaps even assuming that they are infallible. After all, someone who has leadership traits must have superior knowledge. Eventually studies came to look instead at behaviours and whether a leader was task-oriented, people-oriented, directive (a decision maker), or participative. Where certain behaviours are concerned, the problem might lie partly in which sort of behaviour to employ. What happens when business leaders must serve two opposing aims, such as a desire to meet output goals while at the same time ensuring staff well-being?

As the study of leadership evolved, contingency theories became increasingly popular. These asserted that a good leader would need to have more than one style, adapting to fit each situation, so that a combination of behaviours is ultimately more important than any single trait. Those studying leadership behaviour also looked at the degree to which leaders involve followers in decision making. During the past 30 years, focus has shifted to making a distinction between transforming and transactional leaders. It has been frequently suggested that a true leader has to take his or her eyes off the bottom line from time to time, to scan the horizon for developments likely to pose challenges as well as the long-term trends that the organisation faces. A transformational leader should be able to do this and encourage others in the organisation.

As to “vision,” this is often seen as a desirable trait in leaders. A leader lacking vision can hardly lead others. Of course, it could be argued as well that visionaries are just risk takers who happen to get lucky, and for every visionary, there are likely to be innumerable failures. So perhaps an element of risk taking should be included. The transformational leader needs to be a communicator as well, or at least to have people who can communicate ideas to reinforce the vision. There is often a need for at least one dedicated soul in the background serving the vision with perseverance and skill to make it a reality.

Anyone who has worked in a corporation has had both good and bad bosses. Generally a good boss or leader is someone who can guide people to discover their own capabilities. As the corporate hierarchy flattens in an increasingly networked environment, promoting more autonomy is becoming a key skill needed for good leadership. A good leader motivates. A bad leader de-motivates.

To sum up, a key element of leadership may be to share with people a vision, motivating them to achieve it and giving them the means to do so, encouraging them along the way. Along with motivation, leadership involves delegating responsibility.

Why Leadership Is Relevant

Most organisations operate within the confines of command-and-control reporting structures. Nonetheless, whether or not you are currently in a leadership position, you have leadership potential within you. Unlocking your leadership potential begins with the recognition that your unique background gives you perceptions and insights that no one else has. Your contribution matters; the days when leadership depended on having too many male hormones and an overdose of driving ambition, running roughshod over subordinates, are past. The world has entered the post-heroic era of leadership, where the known and unknown challenges of the future demand new approaches and insights.

As long as there have been people grouped together, there have been hierarchies, and with these hierarchies comes leadership. As practiced by government officials, a type of hierarchical management existed already in ancient Imperial China. Russian literature of the 19th century is full of civil servants obsessed with their position in the bureaucratic pecking order.* The modern concept of the corporate manager is a fairly new development, however. During the past century, as corporations grew in size and complexity, businesses found they needed far more managers than leaders. Management skills are probably easier to teach than the qualities that make a good leader. As businesses become successful, they see no need to change. And therein lies one of the problems for businesses and one of the most important tasks for a leader: recognising the need for change and managing it well.

What Do Leaders Really Do?

One definition of the differences between leaders and managers has been proposed by Kristina G. Ricketts, a leadership development specialist. She defines leadership as “a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal,” while management means “to exercise executive, administrative, and supervisory direction of a group or organisation.” According to Ricketts, an individual can be a great leader, a great manager, or both.(2)

It was only in the 1970s that academics bothered even to distinguish between managers and leaders. A study published in 1977 by Harvard professor Abraham Zaleznik entitled “Managers and Leaders: Are They Different?” ignited widespread debate in business schools when it suggested that scientific management methods failed to encourage the qualities necessary to drive individuals to succeed in a corporate environment as leaders.(3) Instead, corporations tended to churn out bureaucrats focused on impersonal goals that preserved the status quo and stifled leadership. With their “conservatism and inertia, organisations provide succession to power through the development of managers rather than individual leaders,” Zaleznik wrote.

Rather than framing the debate as “leader versus manager,” in 1990, another Harvard professor, John Kotter, introduced the idea that leadership and management in fact complement each other. While management is about coping with complexity, organizing, and staffing, leadership looks to “align” people by motivating and inspiring them. It is not a mystical process. In fact, effective business visions “have an almost mundane quality to them.” It is not the originality of the vision that counts, but rather how well it suits the purpose at hand. Rather than downplaying management, he noted that strong leadership with weak management is worse than the opposite.(4)

Companies need a vision. Those that lack a vision, or at least a direction, typically make up for this by substituting long-term planning for direction. In such situations, “even short-term planning can become a black hole” swallowing “an infinite amount of time and energy,” according to Kotter. Another danger is that without a genuine direction to inspire them, managers become cynical and the planning process degenerates into a political game.

One example of the positive power of leadership that Kotter mentions is American Express. Founded in 1850, by the late 1970s the company was facing growing competition from other credit card providers. Lou Gerstner, a management consultant, was named president of the company’s travel-related services. He focused on strategy, choosing to position the company to appeal to affluent customers. He also challenged the notion at the time that discouraged product growth and innovation. A more entrepreneurial culture was introduced. At the same time, the company broadened its market reach, vastly expanding its business overseas. Other innovations included 90-day insurance on purchases made with the card, a platinum card, and a cost-saving and more convenient billing method. The company also introduced a revolving credit card, Optima. As a result of these changes, the division was able to increase its net income by “a phenomenal 500 percent between 1978 and 1987.” Gerstner later went on to head a major restructuring at RJR Nabisco, Inc., before moving to IBM and leading the company through a successful turnaround.

Leading Change

Following from the idea that one of the most important goals of leadership is to allow and facilitate change, companies seeking to implement change often rush to pronounce prematurely that a result has been satisfactorily implemented. They then discover that a declaration of victory, made by managers accustomed to thinking in terms of cycles of “hours, days or weeks, not years,” was contrary to fact—victory had not been achieved, according to Kotter.(5) A lack of leadership, along with what is described as “arrogance, insularity, and bureaucracy” in large and well-established firms can impede transformation. But the solution usually doesn’t arrive in the form of a single, heroic individual capable of swaying thousands of employees to follow his or her lead. Rather, the process requires many people to get on board and participate in the task of leading change. Competent management is also important. Without it, the transformation process can veer out of control.

Leading Successful Change

Leaders who want to manage change must be aware of certain aspects, according to Kotter. To achieve effective transformation requires many aspects. A leader must:

Leadership as a Brand

Whether a company is making pizzas or jet engines, manufacturing or providing services, successful companies often have an easily described set of traits associated with the brand. According to a study published in 2007, written by consultants Dave Ulrich and Norm Smallwood, the “leadership brand” should last longer than any single leader or CEO.(7) The executive at the top is considered credible only as long as he or she personifies the brand. The brand’s vital traits, according to these authors, are the qualities that customers truly care about. The company might even draw up a “leadership brand statement” making it plain what makes its leaders special, while outlining primary leadership standards and supporting the company’s brand in the marketplace. It should be sufficiently flexible to allow companies to change as needed.

Leaders who exemplify the brand should be predisposed to it already and should have the knowledge, expertise, and skills necessary to do well in the organization. Ulrich and Smallwood even formulate a ratio that they believe will produce a company’s future leaders of “50–20–30”: 50 percent on-the-job experience, 20 percent working with mentors and role models, and 30 percent formal training. Training should focus on content rather than on processes: the competence should be useful to both customers and investors.

Transformational Leadership

A further distinction can be made—namely, differentiating leaders who can usher in true transformation from those who merely reach bargains with employees to get things accomplished. A transactional leader approach might involve exchanging rewards and promises for effort. The transformational leader can motivate by driving those involved in the process to go beyond their own interests to think in terms of the greater good. A true leader can expand the range of wants and needs among those individuals in an organisation. The transformational leader raises the level of awareness, while the transactional approach offers compensation based on merit.

Engaged employees are those who are actively involved in their company’s business. Leaders and managers have an active role in increasing the percentage of employees who are engaged. Not only do high levels of engagement among staff make for a more productive, happier work environment; engagement plays a major role in determining how successful a company is. Based on one such study published in 2003 by Gallup, business units that are considered to be in the top half in terms of engagement levels achieve more than 0.4 standard deviation units’ higher composite performance than those in the bottom half.(8)

How leaders achieve employee engagement is considered to be key in their success. The way they approach their role can have a major difference on whether or not they succeed in this task.

Transformational leaders seek to instil a vision and influence followers to act selflessly for the common good. Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi, and Nelson Mandela are examples of leaders who changed nations with transcendent visions.

A study by David Rooke and William Torbert identified seven types of leaders, based on how these might relate to and interpret their surroundings and respond to situations that might pose a threat to their power or safety.(9) Opportunists, as the name suggests, seek to win at any price and alienate those around them. Diplomats are keen to avoid any conflict, which hampers their effectiveness. Experts spend much time gaining expertise and are the most typical of the professionals in the study. They are helped by their desire to continuously improve but can treat those around them lacking their knowledge with disdain. Achievers might clash with experts because they focus on goals, including market demands. Achievers often delegate more and bring in higher revenues than experts. Individualists look for creative solutions and can be highly successful, but they create conflicts if they ignore key processes. Strategists are rare and are most effective as transformational leaders. Alchemists are the most rare types and are highly effective in achieving where others may fail. They can achieve reconciliation between warring factions and usually have high moral standards. They can simultaneously be involved in many different organizations at one time.

A leader can evolve. One of the most common types of transformation involves people classed as “experts” becoming “achievers.” This might be the result of a promotion into a management role, according to Rooke and Torbert. A person who is an expert in a particular area must learn to pay more attention to deadlines in a leadership situation, while managing priorities and performance. They will be confronted not only with finding technical solutions, which they are good at, but with addressing customers’ demands and delivering solutions on schedule. Another type of transformation might involve leaders who evolve into “strategists” or “alchemists.” Their focus might shift from self-fulfillment to looking beyond day-to-day business to find fulfillment through social responsibility.

Both individuals and teams can make similar changes. Most teams at the senior management level operate as achievers, preferring clear targets and deadlines and doing well when situations are adverse and deadlines tight. These teams may never bother to reflect on or take the time to question goals and assumptions. In large corporations, where senior management teams operate as experts, the situation may be worse. Here, there is little “teamwork” involved as such. Like individuals, however, teams can evolve as well. One example would be a financial services firm that emerged from an environment of severe cost-cutting into one calling for vision and innovation. To make the transition, the team had to find new managers willing to experiment. The company began to be seen by outsiders as being innovative, allowing it to attract top talent. Results, too, were better than those of industry competitors.

Good management seeks to promote good leadership. But while the world abounds with examples of bad managers, perhaps what should be even more worrisome are the “bad leaders.” As a study by Barbara Kellerman, a research director at Harvard University and author of the book Bad Leadership has pointed out, the world is actually full of examples of bad leaders. We need to face this situation to fully understand effective leadership.(10)

Kellerman identified seven types or traits of bad leaders: the incompetent, rigid, intemperate, callous, corrupt, insular, and evil. Her examples show that bad leaders can be found in nearly all walks of life. There can be no bad leadership without compliant followers. “Leaders and followers are often locked in a complicated dance,” according to Kellerman, who adds that it is important to understand the dynamics that drive them. The risk of becoming a bad leader is very real. Strategies to avoid this include limiting tenure, power sharing, staying grounded and balanced, keeping focused on the main tasks, and making certain that they are able to draw on a network of people who give them honest feedback.

The Leadership Pipeline

Although it might seem obvious that a company needs to produce leadership in-house, it is not a given that companies offer adequate programmes to replenish the ranks of leaders. Assuming that companies can develop future leaders through planning and execution, and there is generally a shortage of leaders, it makes sense to take a hard look at how a corporation grows these individuals. Perhaps shareholders should be wary of companies where this is not a priority, particularly as, according to authors Ram Charan, Stephen Drotter, and James Noel, the “greatest benefit of a leadership pipeline comes when organisations need to build or re-configure.”(11) The authors believe that with the right training nearly anyone can develop leadership potential. To keep the leadership pipeline flowing, companies should clearly delineate roles and create performance standards for each level. The authors describe the six “passages” in the evolution of leaders in the following transition stages:

- Managing self to managing others: This might be the most difficult transition. The biggest problems are created by new managers who fail to let go of their old jobs. The key tasks include figuring out what needs to be done and assigning work, providing feedback to direct reports including monitoring and coaching, and establishing relationships to build networks to improve dialogue and trust. Regular feedback and coaching at this stage can be very helpful.

- Managing others to managing managers: At this level, it is important to realise that it is not the same to manage others as it is to manage managers. First-line managers must be empowered. Learning to delegate is important, as is learning to share authority. More time is spent training other managers. Groups of individuals must be brought together into effective teams. It is important to avoid hiring “clones” or cronies for jobs. The function also requires someone willing to tear down boundaries that impede work and information flow.

- Managing managers to managing a function: A broader focus is required at this level. Thinking in terms of long-term results and from different perspectives is important. There should be a shift to understanding that the function exists to serve the entire business. The transition to this role demands an understanding of the whole functional unit, not simply those parts of which they possess previous knowledge. To succeed, functional managers must love to learn about what they don’t know. A leader recognises that he or she need not be the expert in every area. This stage is marked by a shift from talking to listening. Classroom training works, but on-the-job experience is especially invaluable.

- Functional manager to business manager: The emphasis shifts to thinking more in terms of cost and revenue. In this position, the focus goes from valuing one’s own function to valuing all functions in an appropriate way. It sometimes requires stepping back to see the bigger picture. Rather than simply fixing a problem, it is crucial to understand what the overriding goal should be. This role also thrusts managers into what might be an uncomfortable spotlight. Success can be measured in terms of providing effective communication, assembling a strong team, understanding how the business can make money, effective time management, and awareness of “soft” issues (culture, feedback, organisational beliefs).

- Business manager to group manager: A key skill at this level is to learn to allocate what might sometimes be scarce resources to promote growth in one business, possibly at the expense of others. It requires prioritising an entire portfolio of strategies and measuring managers based on more than just financial results. The CEO is ultimately responsible for ensuring that his or her business units obey laws, uphold company policy, and enhance the brand, while pursuing a profit. The job requires looking beyond the “what” to the “how”—what lies behind the profit, not simply how much profit is generated. At this level, managers must “become comfortable thinking and strategising about what’s invisible,” which requires being able to envision what lies ahead for the company in terms of markets and potential competition. A key tool to develop leadership at this level is to rely on a set of measurements that includes not just financial metrics but success in developing managers, strategic thinking, “corporate citizenship,” and planning.

- Group manager to leading an entire enterprise: Skills for CEOs go beyond mastering strategic ability and leadership. A CEO must be able to fill key positions with the right people. The job requires being able to deliver “predictable” results, setting a strategic direction by knowing where he or she wants to take the enterprise, enabling two-way communication throughout the entire group, and being able to get things done. Becoming more sensitive and attuned to groups and interests outside the company is important—not just to shareholders but to the media and the general public, regulators, activist groups, and others. But if the CEO is spending far more time polishing his or her image externally, there is liable to be something wrong. The most successful CEOs are be those who have succeeded in the important stages preceding this one.

The Nuances of Training Leaders

It is not enough to have a training programme. Companies must realise that not all competencies are right for each level of development. Specific stages in career development call for different responses, and this must be reflected in training modules. The idea that “leaders are leaders” or that “good people can handle anything” espoused by some companies overlooks the fact that successful leaders’ behaviours and styles must evolve as their careers progress, according to a study published in the Harvard Business Review in 2006. The authors, four consultants and management experts—Kenneth Brousseau, Michael Driver, Gary Hourihan, and Rikard Larsson—argued that decision-making skills that work for senior executives can wreck the career of middle managers. Senior managers can also make the mistake of reaching decisions just as they did as a first-line supervisor.(12) As managers progress up the hierarchy, the style of decision making changes. Most important here is that while lower-level managers assign, explain, and communicate, senior-level managers do more listening than telling. At this level there should be a greater emphasis on understanding than directing. Successful managers learn to adapt their decision making. Others may notice that something is amiss as they progress through the ranks but are unsure what. They try a little of everything, which doesn’t work. “The bottom 20 percent of managers get stuck in this uncertainty zone, where they often remain for the rest of their careers,” according to the authors. “The primary lesson for managers is that failing to evolve in how you make decisions can be fatal to your career.” Good leadership programmes acknowledge that there are differences between the skills for line managers, mid- and upper-level executives, and senior executives. Managers also must learn to adapt their styles to the circumstances. Those who can do so have a better chance of succeeding.

In the book What Got You Here Won’t Get You There, the authors Marshall Goldsmith and Mark Reiter provide a clear rundown of what might be called “bad habits of otherwise highly effective people.”(13) They chronicle their experiences as consultants to leaders, including those in industry and even in the armed services. One message is that leaders must identify traits that are holding them back, even when intuitively they may believe these were the very traits that made them successful. An example is a “brilliant, dedicated” executive, who was extremely creative. His flaw was being a poor listener. In fact, he attributed his success partly to the fact he was a poor listener because this helped him to tune out “bad ideas.” Conceding at last that this was a problem, he grew defensive, saying starting to listen too much could endanger his creativity. Finally he came around to agreeing that it was more productive to give people their say than it was to “justify his own dysfunctional behaviour.”

Another problem is that of the executive who must supply “value added,” even when it is not desired. For example, two top executives were discussing a new venture. When one would volunteer an idea, the other would respond, time and again, by saying that “it was a good idea, but would be better if . . .” In fact the urge to always embellish what others come up with may improve the content of my idea “by 5 percent, but you’ve reduced commitment to executing it by 50 percent,” Goldsmith and Reiter write. Instead, the ownership of the idea has been co-opted, leaving the person who thought it up with less enthusiasm. One way to effectively counteract this is to pause before speaking and ask whether or not the comments are really worth making. The same could be said of another CEO discussed in the book, whose endless debating about ideas left his employees feeling that he had stifled discussion. During talks with employees, leaders must remember that there is usually an inequality in such debates; as in most firms, what the CEO says is the final word.

Another fallacy is believing that employees listen to everything, all the time. A CEO who sent a memo was puzzled because the message didn’t get through. The author calls this behaviour “checking the box”—in other words, assuming that doing something will automatically lead to the desired result. In fact, the CEO had no idea who had read the memo let alone understood it, and even more crucial, who believed it. This means that follow-up is key. If it involves a message, it may take several tries until people “get” it.

Being a leader is not about having a title or holding a position. No matter what character traits one possesses, no one is born a leader. Everyone has the potential to develop leadership, and those in leadership need to keep in close contact with those around them. This includes taking a genuine interest in issues beyond work. Leadership potential is unlocked by delegating responsibilities and offering guidance and training.

Leadership needs to be experienced at all levels of an organisation. Clear communication is key. If others don’t know what is required of them, how can they perform as expected?

CONCLUSION

In today’s environment, a good leader is generally considered less of a commander than a catalyst. Both types of leaders are still needed. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, as in the wake of any crisis, the qualities competent leaders bring to the table are greatly needed.

Many people associate leadership qualities with accomplishments. For others, success might be awards, recognition by peers, or professional accolades. But for some, facing their toughest challenge, even one that is not publicly acknowledged, might be their most satisfying moment. It could involve building a business from the ground up. This can offer major personal satisfaction. It is something every leader should experience, at least once. Everyone’s experiences can offer lessons in leadership. I conclude with some of my personal thoughts on this.

NOTES

1. Doyle, M.E. and Smith, M.K. 2001. “Classical Leadership.” The Encyclopaedia of Information Education, TIME, 1983.

2. Ricketts, K.G. 2009. “Leadership vs. Management,” Cooperative Extension Service, University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Leadership Behavior.

3. Zaleznik, A. 1977. “Managers and Leaders. Are They Different?” Harvard Business Review.

4. Kotter, J.P. 1990. “What Leaders Really Do.” Harvard Business Review.

5. Kotter, J.P. 1996. Leading Change. Harvard Business School Press.

6. Kotter, J.P. and Cohen, D.S. 2002. The Heart of Change. Harvard Business School Press.

7. Ulrich, D. and Smallwood, N. 2007. Leadership Brand. Harvard Business School Press.

8. Harter, J.K., Schmidt, F.L., and Killham, E.A. 2003. “Employee Engagement, Satisfaction, and Business-Unit-Level Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis.” The Gallup Organization.

9. Rooke, D. and Torbert, W.R. 2005. “Seven Transformations of Leadership.” Harvard Business Review.

10. Kellerman, B. 2004. Bad Leadership: What It Is, How It Happens, Why It Matters. Harvard Business School Press.

11. Charan, R, Drotter, S, and Noel, J. 2001. The Leadership Pipeline. How to Build the Leadership-Powered Company. Jossey-Bass, a Wiley Company.

12. Brousseau, K.R., Driver, M.J., Hourihan, G, and Larsson, R. 2006. “The Seasoned Executive’s Decision-Making Style.” Harvard Business Review.

13. Goldsmith, M. and Reiter, M. 2007. What Got You Here Won’t Get You There. How Successful People Become Even More Successful. Hyperion.

*In the programme for the World Economic Forum held in Davos, Switzerland in 2011, the word “leader” was used 44 times. The word “leadership” appeared 26 times, including in the following contexts: leadership under pressure, extreme leadership (mountaineering, polar exploration), the leadership voice (singing), how to inspire leadership (orchestral), how to promote dignity-based leadership, and “mindful leadership.”

*In Anton Chekhov’s story “The Death of a Civil Servant,” a government clerk worries himself literally to death after sneezing on a higher-ranking official.