Chapter 5

Putting Clients at the Centre

It is important to understand the wishes, fears, opportunities, and challenges confronting clients. They are the key drivers in terms of how we shape the organisation to deliver on the promises represented by the brand and associated with the high standards that characterise this industry. One of the great things about private banking is that it allows you to meet people who have much experience and who often have been successful in their lives and careers. You can learn a lot from them. These people come from different walks of life. Each one has a story, from the heiress representing the new generation of a noble European family to a self-made millionaire who started a company in Asia. Each day, it is possible to discover a new facet of an industry, or a country, some interesting fact about an environment, or to meet people who found the right idea at the right time and realised their dreams. Regular meetings with clients are an important part of the business. You need to understand clients thoroughly to ensure that your capabilities and offerings best suit those you are serving. These are people who depend on their banks to keep them informed and preserve their wealth. The following chapter presents an overview and touches on some pertinent topics related to this theme.

MAKING SENSE OF CLIENT DIVERSITY

How many kings can we serve? Private banking began in Switzerland almost 300 years ago when Geneva bankers started catering to the financial needs of a few French kings and noblemen. In recent years, wealth management has undergone dynamic growth and the industry is still expanding. At the same time, it must strive to satisfy the requirements of what is often an increasingly sophisticated and demanding group of clients, each one a “king” or “queen” in his or her own right who deserves to be treated accordingly. How can we build a scalable and profitable business model in such an environment? The answer lies in choosing the clients that will be our focus, then aligning our strategy and all our resources to best meet their needs.

In the 1970s, private banks enjoyed a steady influx of clients whose primary concern was finding a safe haven for their assets. The business environment was more stable, and clients were generally not as demanding as today. Rather than taking an active approach to investing, clients were willing to accept the solutions offered. This more passive attitude allowed relationship managers (RMs) to handle a fairly diverse clientele. A bank might have had some teams focusing on different regions, where foreign languages were necessary. International tax planning experts were available to advise clients. But the organisation rarely reflected the diversity, different backgrounds, and needs of clients nor addressed the various requirements of different local regulatory regimes. In the intervening decades, clients and the industry have evolved so as to be scarcely recognisable, and this has profoundly changed the dynamic of the client–banker relationship. Clients have become very sophisticated, able to access all manner of subjects, including financial topics and market information around the clock via the Internet. Clients also can go online to trade any kind of share or complex financial instrument in real time without needing to call their bankers.

To add value and match the right level of service to the proper client segment, today’s private banker must thoroughly understand the client and provide highly personalised solutions. There are more different types of clients than ever, ranging from those with little financial experience to those whose knowledge is on par with that of professional investors. At the same time, many private and universal banks have gone astray by losing sight of the original concept of private banking—the personal touch. Pressure to grow the business has tempted many banks to lower their minimum investment criteria and scale back service. Meanwhile, a number of retail banks have begun improving their services to the point where they can be considered respectable competitors in entry-level private banking. Globalisation and technology have allowed them to enter new markets, and they can begin to serve clients from widely diverse backgrounds within their own countries. But tackling these new regions requires staff who really understand the local culture and the regulatory and tax environments. The opportunities are limitless, but at the same time, the cost of operating the business has increased enormously. This is especially true when costs of complying with various regulatory regimes are taken into account. This regulatory overhead, an absolute necessity, is associated with every new venture, be it to enter a market, introduce a product, or engage in a different area of activity.

Because of these developments, a private bank must first of all understand the whole range of client segments, groups, and types. It must then decide for itself which of these offers the best opportunities and align its strategy and resources to capture its chosen segment. Chapter 6, “Beyond Products—Offering Tailored Solutions” looks at how a bank can match its offering to suit its chosen clients. This chapter focuses on making a case for segmentation, examining various possible ways that clients, while retaining their individual characteristics and needs, can still be grouped into categories of shared interests and requirements. It also explores in more depth the need for “dynamic” and “behavioural” approaches as opposed to static segmentation. It examines the channels available for attracting new clients and concludes with a discussion of the importance of client retention and some of the tools or approaches that can be used to ensure that clients are well served, to ultimately build on the existing relationship.

ARGUMENTS FOR SEGMENTATION

Segmentation is the process of separating clients into relatively homogeneous groups. The greater the number of different criteria applied, the larger the number of separate groups that can be created. Establishing client segments will allow the bank to tailor service and offerings that are best suited to an individual client’s nature and needs.

Segmentation is a well-established principle of modern marketing and is used in the financial services industry as well. The traditional private banking proposal is a completely individualised one; the ultimate segmentation would be into “groups” of just a single client. So what possible role can segmentation play in a private bank? Segmentation is useful in order to make sure that a bank has the right relationship manager assigned to the right client. Every relationship manager with more than one client also needs to segment in order to manage his or her client portfolio and resources effectively. The benefits of segmentation are numerous.

- Clients can benefit if banks or relationship managers use segmenting to improve the client’s experience—in other words, knowing in advance what typical needs or expectations the client is likely to have.

- Segmentation by country of client domicile allows banks or relationship managers to address regulatory and taxation topics more efficiently

- Banks and relationship managers can identify the most profitable or potentially profitable client group, and focus their resources accordingly.

- Banks and relationship managers can also more easily identify networks or communities and improve referral rates by developing special opportunities for particular client groups with similar interests, such as a passion for modern art exhibitions, attending classical music concerts, or golfing at an exclusive venue.

- Banks can raise their competitive profiles by positioning themselves as experts in specific areas.

- Banks can gain time and resources, which can be dedicated to better serving individual clients.

CURRENT SEGMENTATION PRACTICES

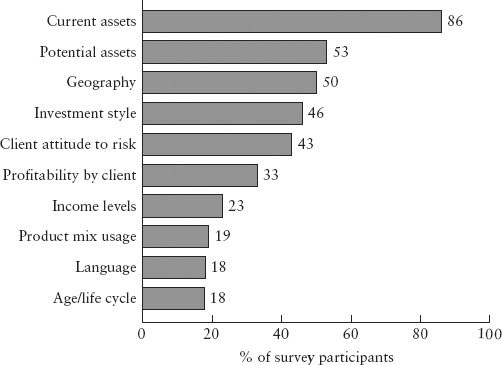

Segmentation is still a very “embryonic science,” according to a 2007 survey by PricewaterhouseCoopers.(1) According to the study, the majority of wealth managers still focus on clients with the greatest number of current and potential assets, meaning those who may offer the highest revenue streams. Other criteria such as investment style, age, personal characteristics, and source of wealth (old or new money) were far less prominent among the segments considered by those surveyed. See Figure 5.1.

FIGURE 5.1 Segmentation Criteria Commonly Used by Banks

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers International Ltd. “A new era: redefining ways to deliver trusted advice.” Global Private Banking and Wealth Management Survey 2009

The study found that some 60 percent of organisations do not differentiate clients by behaviour type. Instead, the vast majority, 75 percent, still treat client risk appetite as the distinguishing feature. Only 62 percent of business managers have specific propositions for certain types of clients. Furthermore, a quarter of organisations surveyed said they did not treat their top 20 clients any differently from the bottom 20 clients. Just 54 percent of products and services, 42 percent of communication and information, and 47 percent of pricing offerings were tailored to specific wealth segments. Finally, when “behavioural criteria” are considered, clients often were just lumped into professional categories such as “entrepreneurs or professionals.” All this is worth noting, given that sophisticated segmentation confers a significant competitive advantage at a time when the war to gain clients has never been more critical, and any failure to understand what clients want will mean that clients are lost to competitors.

Let us next briefly review what segmentation criteria can be used.

SNAPSHOT OF SEGMENTATION CRITERIA

There are a number of segmentation approaches that can take snapshots of the client or the market. These provide a static picture, making them easy to use. But a number of such criteria need to be examined in order to truly understand the individual client and tailor the offering accordingly.

The major criteria used here are:

Level of Wealth

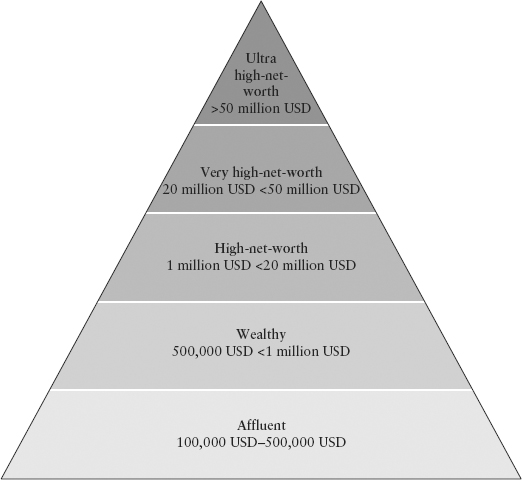

When discussing clients in the financial services industry, age and income are the most widely used segmentation criteria. These are popular because the data are readily available, and there is a strong correlation between these and broadly observed investment and purchasing patterns. In private banking, the level of wealth correlates with age and income. Consider the well-known wealth pyramid shown in Figure 5.2. The definitions of the wealth bands vary from institution to institution. They are expressed here in terms of high net worth (HNW) as follows: HNW ($1m <$20m); very HNW ($20m < $50m); ultra-HNW (>$50m).

FIGURE 5.2 The Wealth Pyramid

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers International Ltd. “Anticipating a New Age in Wealth Management.” PwC Global Private Banking and Wealth Management Survey 2011

Wealth is one of the most fundamental criteria. A minimum level of wealth or at least a potential level of wealth is required to be accepted as a private banking client. In that sense, wealth is the single most important segmentation delineator. It is also used by individual relationship managers to tailor their services, target offerings, calculate fees, control costs, and develop strategies. However, banks begin to organise client teams around such “wealth bands” only when it makes sense, meaning when they have enough clients in any particular group.

There is a common assumption that the higher the level of an individual’s wealth, the more profitable that client will be. But in fact, the profitability may well decline as wealth increases, because wealthier clients are often more sophisticated and thus more demanding, and their bargaining power enables them to negotiate special prices and services. Consider the example of an ultra-HNW client who is a keen trader. To meet his expectations, the bank serving him would have to employ a trader exclusively to deal with his orders, and such clients often feel entitled to discounts on fees, based on the large volume of business they bring. A bank also would need to assign additional executive/managerial attention to the client throughout the acquisition and retention phases.

Clients with $1 million to $5 million in assets are a highly interesting group, being typically diversified and sophisticated enough to try out some of the special structured products on the market. It is possible to deliver excellent service to these clients, without the same range of complexity required by ultra-HNW individuals (UHNWI), including pricing and meeting special demands.

Geographic Origin

While many HNW clients often operate globally, they have clear patterns of needs based on their country of origin. Geographic segmentation once meant, for example, simply assigning a Spanish-speaking relationship manager to Latin American clients. But today, geography can also be a strong indicator of which approach should be used in terms of client investment strategies and their typical needs, allowing a bank to form and refine regional product and service strategies. The following generalisations can be made about clients based on their geographical origins. But as all clients are individuals, these are to be regarded, at best, as simplified guidelines.

Source of Wealth

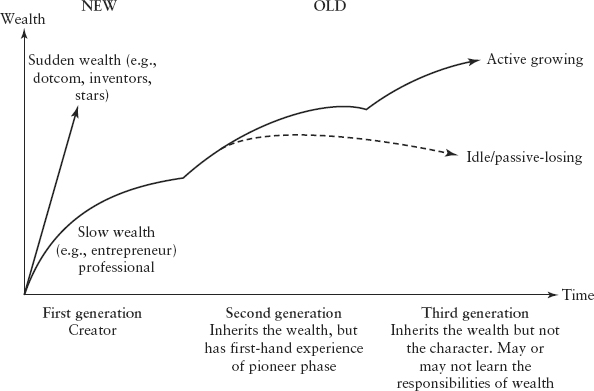

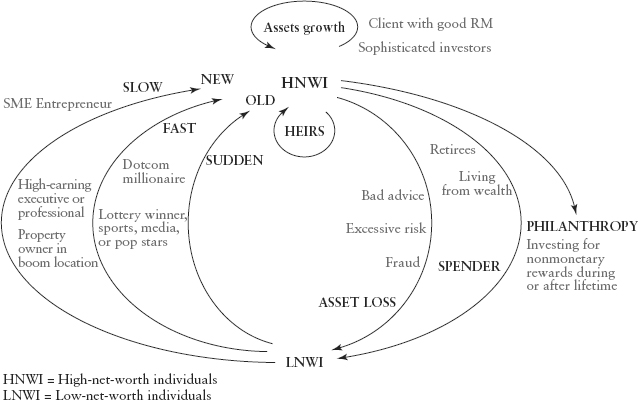

Source of wealth is another commonly used segmentation criterion. The simplest distinction is between “old” and “new” money. New money has been created or earned by the client, whereas old money typically is passed from generation to generation, as is frequently the case in aristocratic or industrial families. Inherited wealth is most common in Europe, and comprises the smallest group of the wealthy in Asia, the Americas, and Russia. However, this will change within a decade or so, at least in the United States, as aging entrepreneurs whose fortunes were made in the post-war boom begin to pass on wealth to subsequent generations. Consider Figure 5.3. It adds two further refinements to the source of segmentation: one is the distinction between first-generation, second-generation and third-generation wealth, and the other is the speed at which the wealth was acquired—in other words, “sudden” or “slow” new wealth. With regard to succession, grandchildren are at least one generation removed from the pioneering efforts that created the wealth, and so it is often a greater challenge to educate them in the responsibilities that wealth confers. This generalisation should not be taken too far, however. A bank needs to reach out to heirs of clients with financial education and bonding exercises, but it must always bear in mind that potentially vast differences in character, education, and attitude can be encountered in this segment.

The relationship manager also may have to find a way to mediate conflicting desires, accommodating the lifestyle needs of heirs while taking on the duty to educate them in matters of capital preservation. The importance of considering both aims can be seen particularly among private banking firms that have served the European aristocracy. Whatever a relationship manager’s degree of influence might be, the ultimate goal should be to help the heirs to gain confidence in financial matters.

Looking at the time frame in which a fortune is acquired over a longer period of time, clients will often be comfortable with financial topics, and tend to be efficient managers or delegators, as well as perhaps being better able to conceptualise risks and strategies. Regional variations also make a difference. For example, Asian clients (apart from Japan) are often entrepreneurial wealth creators.(5) As such, they are more risk tolerant when it comes to a business that they can see, feel, touch, and control.

Unlike the slowly acquired “new” wealth accumulated through 20 or more years of building a career or business, “sudden” new wealth leaves the client little time to reflect, let alone develop an understanding of the ins and outs of managing a personal fortune. It could be money generated by a private business, or from large performance bonuses, or senior executive salaries. Beneficiaries of sudden wealth may feel less confident about money. They might be sports figures or media personalities who earn vast amounts through royalties or sponsoring contracts. This group is often relatively young and financially inexperienced. Exhausting rehearsal or training schedules also place significant demands on these clients’ time. Add to that the intense pressure of public performances, or other professional obligations. The net result is often a client who needs special insurance services, jargon-free explanations, and adequate long-term provisions. Efforts by some banks in recent years to cater to sports professionals, for example, demonstrate there is a business case to be made for targeting specialised groups of clients.

Those who have accumulated wealth steadily have had time to gain expertise in making financial decisions, while those whose wealth arises suddenly often lack experience, and their appetite for risk might not match their risk tolerance. In general, the more sudden and irrational the wealth’s source, the greater will be the client’s fear of loss and the consequent need for secure investments that guarantee a specific level of income. The same principle applies to wealth that was created in unstable economies or in countries where clients may fear confiscation, inflation, or war.

The chart showing wealth waves in Figure 5.3 adds an important element missing from most “snapshot” segmentation pictures: the client’s story. But even here, the source of wealth doesn’t say much about the client’s experience and requirements. To gain a better idea about that, we need to consider behavioural criteria to better understand the client’s needs.

BEHAVIOURAL SEGMENTATION

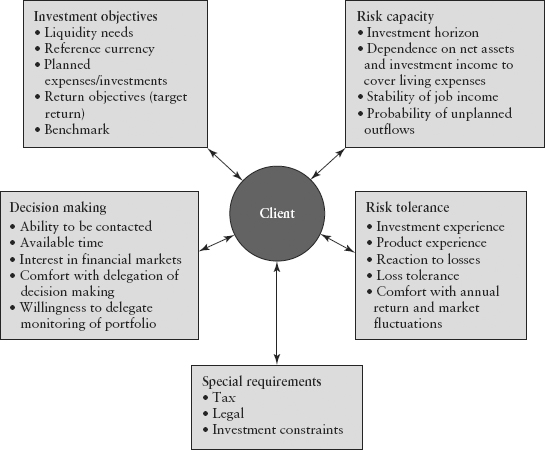

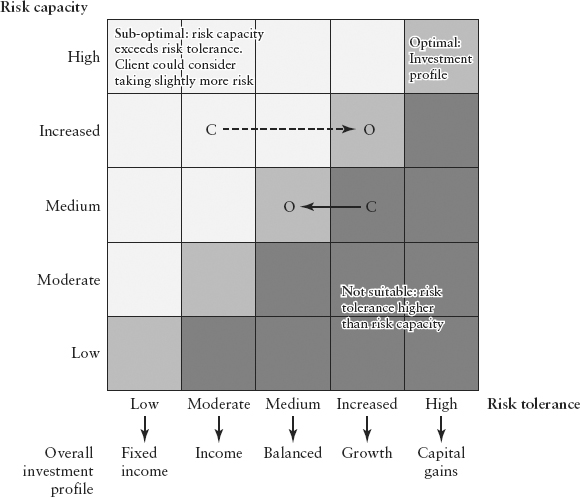

We can categorise clients according to an array of criteria, including their objectives, capacity and tolerance for risk, sophistication, and any specific investment restrictions or specifications in what can be considered the five dimensions that make up an individual’s investment profile, illustrated in the following chart. Although information is available on a client’s product mix and investment style, it is also important to predict what a client might do in future, rather than simply labeling him or her on the basis of past behaviour. This means that a good relationship manager is also something of a psychologist, who, to serve the client in the best way possible, must understand the client’s personality. Does the client prefer to initiate or respond? Does he or she tend to delegate more or prefer to participate? Is he or she a strategist or an opportunist, an accumulator or a preserver?

A relationship manager must assess which approach best suits a particular client during their initial meetings. This is done through a series of analyses to determine the client’s investment type and risk tolerance, by asking questions and using so-called metrics to gain further details. This information can be weighed when determining which investment strategy and related product set to propose.

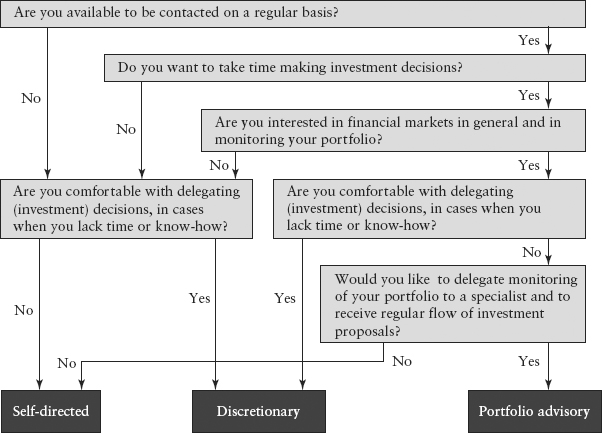

Consider Figure 5.6, which shows how Bank Julius Baer assesses the client’s decision-making style, using a series of simple questions. This allows the bank to determine whether a client is likely to fit into one of three groups: self-directed, discretionary, or portfolio advisory.

Consultants have identified at least three profiles based on behaviour, which can be effective ways to segment clients: are they delegators, participators, or selectors? There is even a fourth category comprising ultra-high-net-worth individuals. Creating this separate category can be justified on pragmatic grounds, as there is some validity to the argument that being an UHNWI is associated with a set of specific needs and behaviours sufficient to justify a separate segment, providing that the bank has a sufficient number of these clients.

- Delegators desire asset management solutions requiring only slight involvement, in effect outsourcing their responsibilities to the private bank. They need a reliable and empathetic professional advisor, clear responses, effective reassurance, and disciplined management.

- Participators want more involvement in the decision-making process. Investment is an enjoyable hobby to them. They need to be supplied with a good stream of investments from which to choose and want access to what they consider to be privileged information or opportunities.

- Selectors are financially sophisticated investors who pick and choose their products and services. They need to see products and services they consider innovative, along with high standards of delivery and a long-term investment in the relationship.

- UHNWI clients demand higher levels of individualised service and an intense focus on their needs to a greater degree than any other client group. Their expectations change rapidly, and these clients purchase services in a manner that is almost institutional. They demand extremely professional service, complexity management, and networking opportunities.

Segmentation along the Client Wealth Life Cycle: Keeping an Eye on the Bigger Picture

To visualize the wealth dynamics of clients, we can use the Wealth Life Cycle represented in Figure 5.7. On the left side are those who are amassing assets, becoming high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs). On the right side are those who are using up their capital base and are reducing wealth, becoming lower-net-worth individuals essentially (LNWIs).

The paths shown by arrows correspond to various routes to riches, and alternatively, to losing or giving up wealth. The longer arrows indicate a slower transformation. Slower increases and decreases in wealth are placed further to the outside. Clients experiencing faster gains and losses are positioned closer to the centre of the diagram. At the top, we see one feedback loop for inheritance and one for asset growth.

On the declining wealth side, we find victims of fraud or bad advice in addition to those who have miscalculated their risks. Rich pensioners, those people living from their wealth, and philanthropists may also see their asset base decline, though this latter group probably will not mind at all. Some experts believe that the future of private banking is incomplete without a strong line in philanthropy consulting, based on the perception that portfolio growth is relatively uninteresting to HNWIs above a certain level and that a bank can therefore differentiate its brand by helping these clients use their wealth to leave a meaningful legacy. The largest banks have recognized this trend and offer specific philanthropy services for their private banking clients, including not only families that in the past might have set up private foundations, but also those with less wealth, who nonetheless would like to take the initiative and contribute to society, address problems affecting the environment, or support other specific causes.

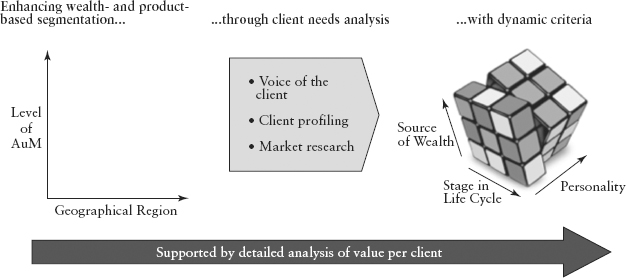

Trying to gain a more client-centric view, it is necessary to move from a static snapshot to dynamic representation, as shown in Figure 5.8. Within the bigger picture, clients are likely to be busy building a business, amassing a fortune, securing or enjoying a lifestyle, while providing for the future or leaving a social legacy through philanthropy. The private banker will be just one of a string of advisors contributing to the flow of ideas or solutions in this process. In all cases, it is wise to remember that clients do not want their “relationship” managed. They want their assets managed. They desire the highest level of service, ideas, and performance, all at the appropriate risk level and without any legal or fiscal complications.

Segmentation requires effort; it needs time and resources for systematic research, looking both at existing and potential clients, as well as markets. It can be costly and time-intensive. This is why the use of segmentation approaches depends very much on how many clients ultimately might be included.

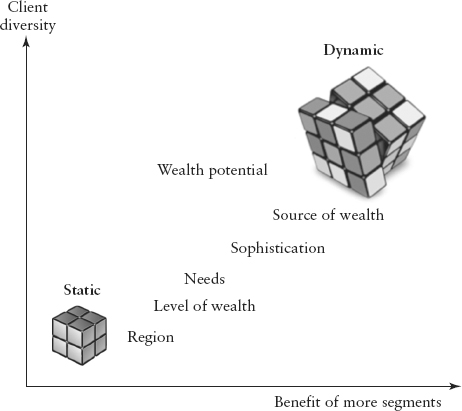

As illustrated in Figure 5.9, the more diverse the client base, the more value can be derived, for both the bank and its clients, from each additional segmentation level, or dimension. If segmentation produces some key insights and “eureka” moments, there also may well be some internal challenges. A bank might need to reorganise its business to effectively use the insights gleaned from segmentation.

FIGURE 5.9 The Relationship between Client Base Size and the Increased Benefit of Segmentation

Source: Author

Finally, one must keep everything in perspective. Each private bank has its individual approach to business. In the end, it does not matter how clients are segmented as long as you align your resources accordingly. The bottom line is to choose the right solution for the client and the business.

ATTRACTING NEW CLIENTS

Having determined which clients you will target, you need to align all the resources of the organisation in order to attract and retain these clients.

This section covers possible avenues to gain new clients and how various factors can have an impact on the process. It then discusses the importance of client retention and specifies some basic tools to provide an early warning as to whether a client might be contemplating switching to another provider.

Channels and Tools

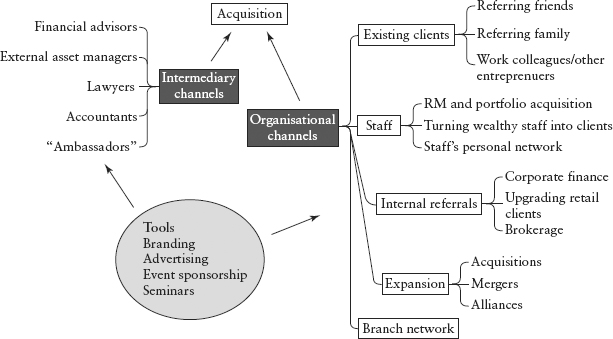

There are two channels private banks can employ in seeking new clients: Figure 5.10 depicts both the organisational channel and a second channel via intermediaries. Both can serve as ways to gain access to potential clients; in the figure that follows they are ranked from most to least important. A range of tools representing specific activities is shown at the lower left.

Organisational channels are those that draw in clients by virtue of the organisation’s existence. They include current clients, staff, organisational or internal referrals, the outcome of organisational expansions (mergers, acquisitions), and the physical presence of the bank in the form of a branch network.

Intermediary channels are all types of third parties or individuals outside of the organisation that have regular contact with clients on behalf of the bank, be it on the basis of paid commissions or through informal relationships. These channels include independent financial advisors, lawyers, and even famous personalities. Tools such as branding, advertising, and event sponsorship or seminars can be part of both the organisational and intermediary channels.

The most rewarding acquisition sources are referrals from existing clients, indicating that they are satisfied with the service. This is a compliment to any bank. In addition, internal referrals and referrals from all types of intermediaries may play a part. The staff channel is also a major source for recruitment of a relationship manager who can bring a portfolio of clients to the bank.

These widely recognised sources are used to a varying degree. Most banks have a formal process for “incentivising” intermediaries. Internal referrals (such as when clients are recommended from another part of the bank) may be encouraged, but on a less systematic basis. This also depends on the bank’s culture. Client referrals are generally under-utilised. Few relationship managers have the courage to ask their clients for referrals directly, even if clients would be happy to provide them. Relationship managers, it must be underscored, need to be courteous to clients but perhaps a bit more open in this respect. Indeed, research indicates that most clients are actually happier with the bank than most relationship managers assume. Therefore, these clients are likely to be more open to a referral request than the relationship managers generally would expect.

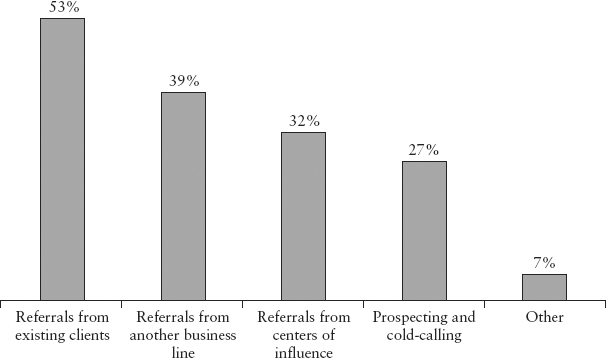

In a survey conducted by the VIP Forum in 2008, over 2500 advisors across 33 financial institutions were asked to approximate the percentage-amount of referrals (from a given referral source) that would result in new client business. As illustrated by the survey results in Figure 5.11 “Referrals from Existing Clients” convert to new business at the highest rate compared to the other referral sources—53 percent of referrals from existing clients result in new business compared to “Prospecting and Cold-Calling” where only 27 percent result in new client business.(6)

FIGURE 5.11 Percentage of Referrals Resulting in New Client Business (per Different Source of Referral)

Source: VIP Forum. Corporate Executive Board, “Boosting Advisory Productivity: Benchmarks for Developing and Managing World-Class Advisors,” Arlington VA, 2008

It is tempting to believe that it is feasible to do away with marketing and brand building in order to focus on the most fruitful channels for gaining clients. But marketing managers need not fear. Today it is no longer possible to do without them. A broader approach taken to serve a variety of clients along with increased transparency in recent years have increased the need to position the brand. To reconcile these seemingly conflicting aspects, the client’s choice of a bank ultimately comes down to a range of factors. Attributing it to any one single motivator will always be a gross oversimplification.

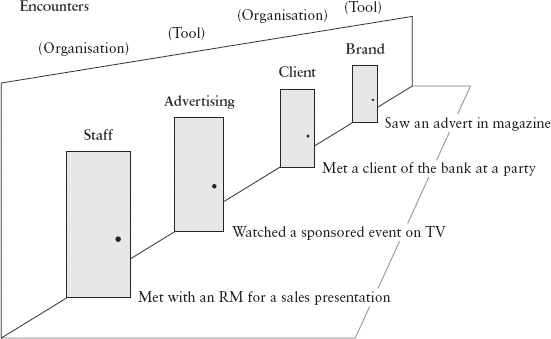

The client corridor approach (see Figure 5.12), also described in Chapter 8, “Delivering a Superior Client Experience,” is a helpful analytical tool that can be applied to better understand the impact of organisational and marketing influences. Out of four encounters that contribute to an individual’s journey from being a prospect to a becoming a client, two are based on organisational channels, and two on what one could call tools such as advertising and brand. In reality, there might be an intermediary channel involved, and there would be many more touchpoints or encounters along the way.

FIGURE 5.12 The Client Corridor Visualises and Assesses all Encounters between the Prospect and the Bank

Source: Author

RETAINING CLIENTS OVER THE LONG TERM

Long-term client relationships make sense for both the client and the bank. A trusted advisor relationship must be built over time, so retention is key to achieving good relationships. For the bank, taking on new clients represents a significant cost factor. For the client, switching banks can be disruptive. Some clients remain with a single bank throughout their lifetimes, a fact that can enhance a valuable relationship.

Client Lifetime Value

One obviously cannot put a value on a human being. For the purpose of private banking, however, the client–bank relationship creates value for the client and the bank over time; the more successfully the client’s wealth is managed, the more profitable the relationship is likely to be for both the client and the bank. The bank might also look at a client as generating a value that goes beyond the current profit margin. To calculate the value of a client in the sense of his or her contribution to a bank’s earnings, bankers sometimes evaluate the combination of the client’s “market potential” and “resource potential:”

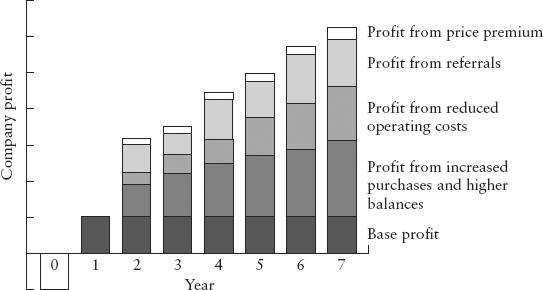

The components contributing to the improved profitability of the relationship over time are shown in Figure 5.13. As the relationship manager gains the client’s confidence, this leads to increased transaction- and asset-based fees, and proportionately lower administrative and distribution costs. At the same time, a satisfied client will generate referrals. If agreed at the beginning when the account was opened, the client may also see some discounts phased out over time, but again this must be made clear to the client at the outset.

FIGURE 5.13 Components of Company Profit Increasing over Time

Source: Reprinted with permission from “Zero Defections: Quality Comes to Services” by Frederick F. Reichheld and W. Earl Sasser Jr. Harvard Business Review, September 1990; Copyright 1990; all rights reserved

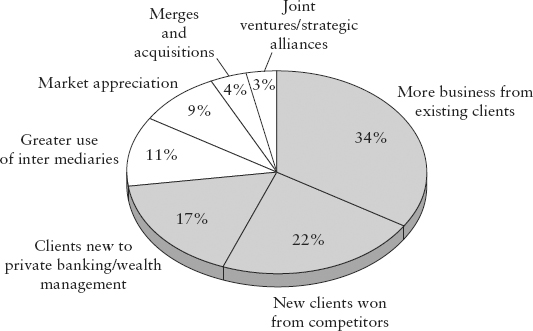

The benefits of long-term retention are evident in Figure 5.14. It shows that most of the growth of profits—34 percent—comes from the increase in business from existing clients. It also makes an interesting distinction between clients acquired from the competition (22 percent) and clients who are completely new to wealth management (17 percent). PricewaterhouseCoopers’s Wealth Management Survey 2007 came to the conclusion that there is still plenty of potential for relationship managers to increase the “share of wallet,” meaning the percentage of assets of a particular client managed by the bank. The survey found that fewer than half of the wealth managers surveyed were holding more than 40 percent of their client’s investable assets. It would be clearly to the advantage of these managers to hold more of their clients’ assets. According to the survey, this proportion is forecast to increase significantly, concentrating almost 80 percent of wealth managers holding over 40 percent of a client’s wealth.

FIGURE 5.14 Contribution to Growth in Revenue of Various Sources

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers Private Banking/Wealth Management Survey 2003

Although it’s a zero sum game for the industry as a whole, increasing wallet share is nonetheless one of the easiest ways to increase profitability at individual banks. It also has the advantage of creating stronger bonds between the client and the bank, making him or her less likely to follow a departing relationship manager. The final point to mention is that a larger share of wallet leverages the critically scarce resource—the relationship manager—and as long as clients are satisfied, this also should generate more referrals to bring in new clients.

In sum, it makes most sense to focus directly on achieving the highest level of client satisfaction. If you can please the client by offering him or her solutions to problems and opportunities for strong performance, the client will automatically entrust you with more assets. Again, the key lies in knowing what the client really needs. This takes us back to the subject of segmentation, which will allow us to better understand the client’s needs and adapt or shape the strategy, products, and services accordingly. We also still need talented relationship managers capable of understanding clients’ needs and expectations and who can breathe life into the relationship.

The Value and Challenges of Bonding

Not only can humans bond, it is also possible for clients to bond with brands. The “Brand Emotional Loyalty Pyramid” describes five sequential levels that the strength of a client’s relationship with a brand can reach: No Presence, Presence, Relevance and Performance, Advantage, and Bonding. A client can only be attributed to one level and must satisfy all preceding level requirements in order to move to the next level.(7)

According to an article by G.R. Hallberg in Ogilvy & Mather’s Newsletter “Emotional Loyalty: The Key to Marketplace Success,” a client at the top level of the pyramid—the Bonding stage—believes that the “brand’s advantages are unique, or shared by few other brands.” One level below are people who believe the brand offers some “quality that gives a reason to buy it over others,” followed by those on the next lower level, who believe the brand is relevant to their needs and provides suitable performance. On the second lowest level of the pyramid are those who are simply aware of the brand and have heard about it or tried it before. Those for whom the brand is unknown or not relevant make up the bottom rung where the client has no emotional loyalty at all.(8) According to a study by IBM Business Consulting Services, most companies manage to shift only 10 percent of their customers to the Bonding stage, the top level of the pyramid. But it is well worth the effort: a shift from level 2 Presence, where a customer is merely aware of the brand, up three notches to Bonding can on average increase the customer’s value to the company by more than seven times.(9) Furthermore the average value of a customer almost triples between the Advantage and Bonding stages.(10)

The nature of private banking means that the strongest bonds tend to develop primarily between the client and the person most likely to be the main point of contact, the relationship manager. This is a strong functional bond as a result of the relationship manager’s unique understanding of the client’s background, business, and financial position; an emotional bond exists as well, formed by the trust developed over time, along with the shared experience of riding market highs and lows. This creates a rather problematic side effect. Losing a relationship manager usually means losing clients. Client experience in conjunction with strong brand management and retention tools have an important role to play in tackling this problem. The Chapter 7, “Why Brand Matters” and Chapter 8, “Delivering a Superior Client Experience” delve into these topics at length. But first it is worthwhile to look at retention tools.

Retention Tools

A tool is a piece of equipment, a system or a process that with the proper resources allows someone to complete a specific task more efficiently. Events and sponsoring can be considered tools in private banking when used by relationship managers to bond with the client and increase the loyalty to the brand. Similarly, events designed to provide a lasting, positive impression on the client’s heirs while developing their financial acumen also can be considered retention tools if they pave the way or simplify retaining assets when the inheritance is received.

Customer relationship management (CRM) systems are tools that improve the quality and presentation of information available to relationship managers to help them manage the client relationship. The ideal CRM system should offer a wealth of timely intelligence regarding the client’s behaviour and preferences, so as to help the relationship manager in offering solutions better suited to the particular client’s needs.

Early Warning Signals

Early warning systems are very useful in allowing the relationship manager to respond to problems that might be developing in a relationship. Signals that something might be amiss include infrequent client contact, poor performance, asset outflows, changes in activity patterns, demanding discounts, switching mandate types, changing relationship managers, complaints, and operational losses.

- Infrequent client contact

Even if the client seemed quite satisfied at the time of the last contact, infrequent contact is a signal that the risk is increasing that a client might defect. The client’s needs might have changed, or competitors are actively courting the client. Clients should always be contacted at regular intervals, unless they request otherwise.

- Poor performance

Even when all relevant benchmarks and markets are down, the client still feels the pain of negative performance and needs reassurance at such times. It may also be necessary to propose a change of strategy. More often than not, clients tend to be more risk tolerant when markets are positive, but they become more conservative when markets decline.

- Asset outflows

Clients rarely decide to close an account from one day to the next. They usually drain their accounts over 6 to 12 months before finally closing it. Net outflows or negative net new money (NNM) of more than 25 percent of the client’s total assets over six months can be an early warning sign.

- Changes in activity patterns

The CRM system can be configured to monitor the frequency of transactions and then to respond to any deviation beyond a certain tolerance level if there is an indication that something about the client relationship requires special attention.

- Discounts

With some clients, demands for discounts could be a sign that the bank’s pricing is no longer competitive.

- Change of mandate type

A client may switch from a managed account to advisory mandate as an appropriate response to changing needs. But this might also be a “quick fix” response to satisfy a desire for better value or a cheaper service. This is almost always a sign that the relationship could benefit from some additional action and attention on the part of the relationship manager.

- Change of relationship manager

The CRM early warning system should flag all clients who have been passed to a new RM—for example, due to retirement of a long-standing trusted advisor. These clients require special attention and must be reassured about the continuity of the banking relationship.

- Client complaints and operational losses

A written complaint should always be viewed as a highly serious matter. The action of writing indicates a commitment or desire to fix the relationship with the bank, as opposed to a termination of the relationship and transferring the assets to another bank. With the appropriate response, the bank can turn the situation around and actually increase loyalty.

In any situation where an early warning signal is detected, the response should be conciliatory and positive, focused on finding solutions. The relationship manager should be willing to go the extra mile with the client. This topic is addressed in Chapter 8, “Delivering a Superior Client Experience.”

CONCLUSION

Understanding clients is crucial to acquiring, retaining, and developing a relationship in an increasingly competitive environment. Banks need to use segmentation techniques more effectively to develop innovative offerings and to enhance relationships with clients. No matter which segmentation approach is used, the wealth manager will need to employ all resources at his or her disposal to effectively serve clients and to reach out to prospective new ones.

Clients in general have become more sophisticated and are being courted with growing intensity in an increasingly competitive environment. To combat rising costs and other challenges to profitability, private banks need to look at the market in tiers or slices, choose the groups or segments they can serve best, focus on these, and align all of the organisation’s resources toward serving their chosen group of clients effectively.

Surveys suggest that current segmentation practices focus too heavily on static snapshot criteria and place too much emphasis on the clients’ current levels of wealth. Efficient segmentation does not imply a rigid approach, meaning specific product lines targeted at particular client segments. Segmentation means that the relationship manager is in position to better understand the client. Then he or she can match the client’s needs with solutions. An experienced relationship manager can absorb a wealth of information about a client and process it more intuitively and more efficiently than any CRM system is capable of doing. With that in mind, one can conclude that the focus of scalability efforts, rather than just gathering more data on clients generally, needs to evolve toward giving relationship managers better means to choose the best solutions for individual clients, based on what they know about these clients.

Support for a segmented approach should not be regarded as a call to uniformity. Instead, it is driven by the desire to better understand the client while improving the efficiency with which individual services can be delivered. It is about shedding the distractions that arise when one tries to be all things to all people. Once this has been achieved, it is possible to create a truly client-centric organisation that focuses on the client’s stage in life and individual needs. It is important to switch to a more dynamic perspective, one that takes into account the client’s entire set of needs and how these contribute to a long-term profitable relationship. This benefits not just the bank but also the client. It is a given in an industry claiming to be focused on long-term relationships. It is therefore important to understand and adapt to client needs and changing requirements in the immediate context and align resources accordingly.

As discussed in the following chapter, “Beyond Products—Offering Tailored Solutions,” it is not important just to determine the client segments that ought to be the main focus. It is also crucial to find the right solutions to best serve these various groups.

NOTES

1. Weatherill B., Ed. 2007. PricewaterhouseCoopers Private Banking/Wealth Management Survey, Unprecedented Opportunities, Plan Your Approach, Global Private Banking/Wealth Management Survey: Executive Summary.

2. RTS Exchange. RTS Index History Chart Period 31 Dec 2007–31 Dec 2008.

3. Ustinova, A. 2009.“Party Ends for Russian Rich After $230 Billion Losses,” Bloomberg News, April 9, 2009.

4. Nelson, Choi N., Leung, F., Tang, T., and Wu, C. China Wealth 2010: Wealth Markets in China, Capturing the Multifaceted Growth Opportunities. The Boston Consulting Group.

5. Ernst & Young. 2010. Greater China Leads Global IPO Activity in 2010.

6. VIP Forum, Corporate Executive Board. 2008. “Boosting Advisor Productivity: Benchmarks for Developing and Managing World-Class Advisors,” Arlington VA, 2008.

7. Hallberg, G.R. 2002. Ogilvy & Mather’s Viewpoint: Emotional Loyalty: The Key to Marketplace Success.

8. See note 7 above.

9. Howlett, N. 2005. IBM Business Consulting Services, Customer Experience Management. “20:20 Customer Experience, Forget CRM—Long Live the Consumer!”

10. See note 9 above.