Chapter 6

Beyond Products—Offering Tailored Solutions

Different clients represent the full spectrum of individual needs and requirements, and this influences the products and services that a private bank provides. A client in Asia, for example, doesn’t necessarily require the same product as one in Brazil. Thus, products and services need to take into account this diversity and ensure solutions that are tailored to match each specific client’s needs and regulatory constraints. As a result of the “new paradigm” in private banking characterised by increased transparency and greater compliance in tax matters, cross-border clients are likely to be more open and willing to initiate a genuine dialogue with their banks. Such increased interaction will enhance product development. With regard to products, it might be noted that some have features that are easily replicated and can thus be described as commodities. Products that fall into this category might be outsourced. But it is important to keep control over the process to ensure a uniform, high level of quality.

Looking at some of the most successful investment strategies, a long-term value-driven investment strategy offers the greatest opportunities. Investing in a long-term trend means taking into account developments shaping all aspects of our lives over the coming decade and taking advantage of those countries, sectors, and companies that will benefit from these forces. The important trends are “planet” (i.e., natural resources, agriculture, and renewable energy); “people” (i.e., technology, including social networking and mobile communications, healthcare, and education); and “growth markets” (i.e., emerging markets vs. core markets). It is impossible to approach the discussion of providing clients with investments unless a great many factors are taken into account. These pertain not only to the external aspects affecting investments (markets and the evolution of financial products). Of great importance, too, is how specific products and services are offered to clients, viewed in their entirety rather than on an individual basis. Ultimately the advisory process brings together all the different strands that, when unified, produce a result that, ideally, is specifically tailored to the clients’ needs and goals.

CRISES AS CATALYSTS

In recent years, several crises have rattled markets, although perhaps none was felt so deeply by so many as the financial crisis. Of truly global proportions, it left a lasting impression in the minds of investors. Major losses can occur due to the actions of a single rogue trader or from localised upsets. Markets might be destabilised by mismatches in assets and liabilities or as a result of natural catastrophes. Problems may surface in assets normally deemed safe, such as bonds issued by sovereign nations. Recent decades offer numerous examples of things that can affect financial markets: the Latin American debt crisis in the 1980s, the Asian crisis in 1997–1998, and the collapse of US hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, the same year that Russia defaulted on sovereign debt. There was the bursting of the dotcom industry bubble in 2000–2001. Catastrophes such as the devastating earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011 or unrest in regions supplying key resources such as those in the Middle East may take a toll, as may fears about possible defaults among European countries. But the turmoil that enveloped markets from 2007 to early 2009 demonstrated the dramatic impact that such an event can have on peoples’ livelihoods and personal wealth.

This particular crisis left a deep and lingering mistrust of financial intermediaries among wealthy private clients. As briefly discussed in Chapter 2, “What Is Driving Private Banking?” wealthy clients have become more sophisticated, making them increasingly likely to register displeasure when returns fall below expectations. Most suffered from the problems that culminated in the acute disturbances and dislocations, including the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the autumn of 2008. That not just mainstream asset classes but even structured products originally designed to mitigate losses were hit was doubly unsettling. Hedge funds and hedge funds of funds similarly suffered losses as investors redeemed significant holdings in alternative investments.

There was also a frighteningly systemic aspect to all this. Given the magnitude of these events, it is not surprising in the aftermath of the crisis that some companies in the wealth management industry have begun to reexamine how they approach their main business. For private banks, these events have forced a reassessment of how to best serve clients’ genuine long-term needs. With that in mind, this chapter looks at how product and service offerings to private individuals can best be adapted to serve clients in what has become an increasingly complex and challenging environment.

Prior to the financial crisis, organisations serving private clients typically focused on products. In terms of wealth “aggregation,” products represent the lowest level of client specificity. Products are often designed without taking into account the needs of each individual investor. In the wake of the financial crisis, particularly after losses in the more esoteric instruments, some banks have begun to reconsider the products they offer and how they might best align their services to serve clients. But it’s not only banks that are reexamining their approach. Clients, too, are looking at things in a different light. They demand more transparency and in many cases want to be better informed about the advisory process, which leads to tailored investment solutions.

Private wealth managers in particular have started to reexamine their basic notions regarding products and services. As a result, some are moving from a focus simply on “products” to a more comprehensive emphasis on “classic” private banking services, taking into account a broad spectrum of elements, which include advisory services. They also tailor the advice they offer to ensure it matches each individual client’s needs. Banks going this route are consequently deemphasising products in favour of a more individualised service- and advisory-oriented approach. By moving in this direction, these banks are now free to recognise products for what they are—essentially “bundles” of services, each suited to different levels of wealth aggregation, ranging from broad, general categories suited to many clients to extremely individualised offerings matching the needs of just one individual.

It is not only products that are being viewed in a different way. Services, too, can be categorised in terms of how specifically tailored they are to individual clients. Some services are quite generalised, being provided in identical fashion to all clients; whereas other services, by contrast, are quite specific, designed to meet one particular client’s needs. Furthermore it is important that changes in the business and regulatory environment are fully reflected in the services offered. Since the financial crisis, for example, there has been a greater demand for capital preservation solutions. Clients today also want investment advice that fits all aspects of their particular stage in life and their personal situation. Besides all of these factors, the ever-changing and in many cases stricter international regulatory environment plays an increasingly important role.

The end result is that today, private banks offering products and services need to think in terms of providing enhanced portfolio management while adhering to strict guidelines governing risk and regulatory requirements. Clients need access to “best-in-class” investment solutions and asset managers rather than simply the usual array of standard in-house products. Furthermore, relationship managers (RMs) need to adopt a structured and comprehensive advisory approach with respect to the solutions and services they provide, to enable clients to achieve their long-term wealth management goals. From the perspective of the wealth manager, it becomes extremely important to define the solutions and services that a bank intends to offer. Once that has been determined, systems, processes, and controls should be put in place to make certain that the solutions and services are the right ones and are suited to each individual client.

HAS VOLATILITY BECOME THE NEW “NORM”?

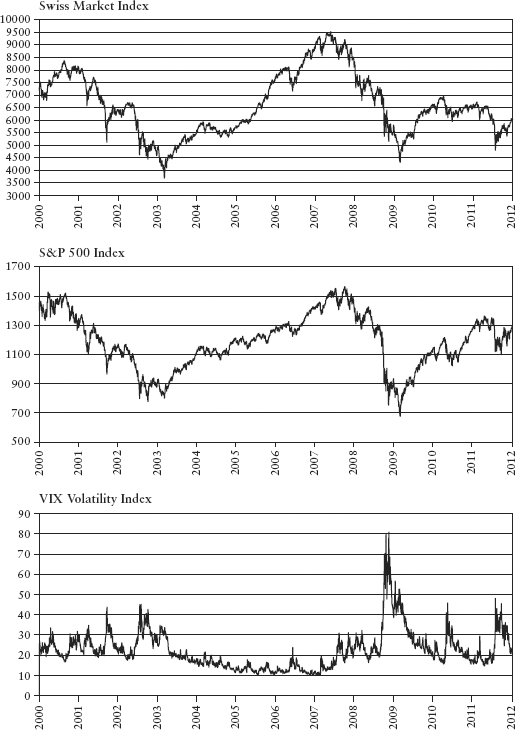

The crisis in the financial system that began in 2007 and lasted into early 2009 proved to be a major challenge for clients and wealth managers alike. Many markets turned negative, and correlations between markets increased in ways that surprised even seasoned professionals. Consider Figure 6.1, which shows the performance of a number of markets during the period from 2000 to 2012. At the height of the crisis, not only equity markets but also other asset classes such as commodities suffered, under pressure from fears of flagging global growth. These experiences and changes in the markets have led investors, including wealthy individuals, to take a closer look at the way their wealth is managed.

If nothing else, the past decade has been characterised by extreme volatility. After setting an all-time high early in 2000, led by demand for technology stocks, major equity indices fell when the dotcom bubble burst. They then began to rally anew, helped by liquidity provided by central banks, so that by 2007 the S&P 500 Index set a new all-time high. In the subsequent crisis through March 2009, the S&P had lost over 50 percent, falling to its lowest level since 1996. But the market then rebounded, ending 2009 with a gain of 23 percent, followed by another positive year in 2010. That trend continued until the middle of 2011 when markets moved into another period of significant volatility. Movements in Asian stocks were even more pronounced during this period. The Hong Kong Hang Seng Index more than tripled in value between 2003 and 2007, only to fall back to levels last seen in 2004. Shifts in market sentiment were reflected in the VIX Index, the market’s so-called “fear gauge,” reflecting the volatility of US stocks. It rose from levels of between about 10 and 30 to spike as high as 80 in late 2008 at the peak of the crisis. Meanwhile, fueled by safe-haven demand, government bond prices rose, so much so that in some cases investors accepted even “negative” real yields. Commodities behaved erratically. The Dow Jones–UBS Commodity Index, which had surged in mid-2008, collapsed by year-end, only to start climbing once again as growth resumed, particularly in developing nations. Reflecting a drop in global trade and overcapacity in the shipping industry, the Baltic Freight Index, viewed as a proxy for global trade, slumped during the crisis, influenced by sluggish demand and overcapacity in the industry.

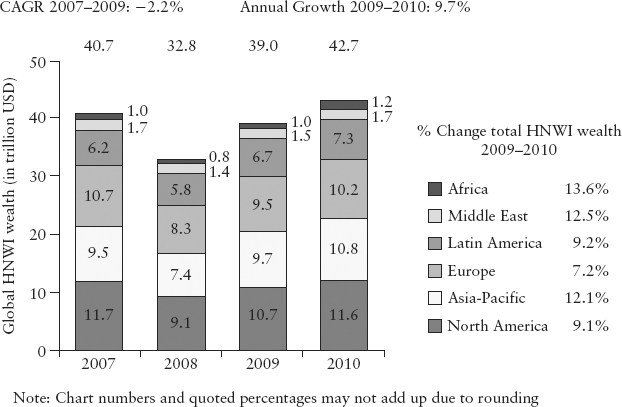

These market developments had a major impact on net wealth of high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs). According to the Capgemini Merrill Lynch World Wealth Report, Latin American clients were least severely hit, while wealthy private individuals in Europe, North America, and Asia suffered most, losing in each case over 20 percent. Wealth has since recovered, as shown in Figure 6.2.

FIGURE 6.2 HNWI Wealth Distribution, 2007–2010 (by region)

Source: Capgemini Merrill Lynch Wealth Management World Wealth Report 2011

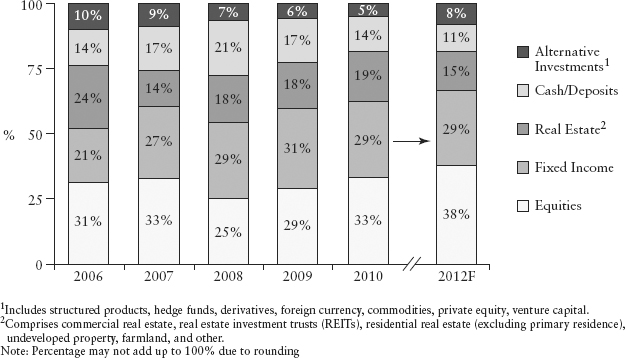

When there is trouble in markets, clients usually become more conservative. Figure 6.3 shows how asset allocations changed between 2007 and 2008; there was a major shift to cash and fixed income, perceived as “safer” at the expense of riskier asset classes such as equities, real estate, and alternative investments. This trend reversed in 2010 as risky assets recovered.

FIGURE 6.3 Breakdown of HNWI Financial Assets 2006–2012F

Source: Capgemini Merrill Lynch Wealth Management World Wealth Report 2011

Even though markets have since stabilised, investors remain cautious. Clients who suffered losses are seeking new, simpler, customised solutions to protect real wealth, especially in times of higher market volatility and stress.

THE ROLE OF FINANCIAL SERVICES AND PRODUCTS IN WEALTH CREATION

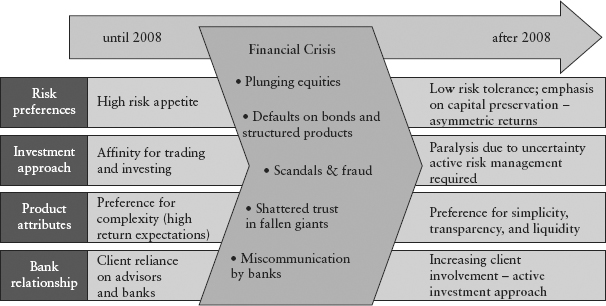

As discussed previously, the impact of events during the crisis years led to changes in how investors think about products and services. This is outlined in Figure 6.4. This chapter focuses on the two aspects shown in the lower-left corner influencing product choices (a shift from more complex to easy to understand) and banking relationships (clients have become more proactive).

FIGURE 6.4 Clients’ Approaches and Attitudes toward Money Management Have Changed after the Financial Crisis

Source: Adapted from Global Wealth 2009: Delivering on the Client Promise © 2009, The Boston Consulting Group

With regard to products, after experiences during the crisis years 2007–2009, it may be a fair question to ask whether financial instruments truly promote wealth creation at all. For a long-term perspective, consider historian Niall Ferguson’s book, Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World. It explores the beginnings and subsequent development of government bonds, which, along with an increasingly sophisticated financial system, allowed the British Empire to govern at one point a quarter of the world’s people.(1) In his subsequent book, The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World, Ferguson looks at the relationship between the development of financial services and how these allowed humans to evolve from hand-to-mouth subsistence into a society enjoying a high level of civilisation and the benefits of technology.(2) Evolution in markets, too, it can be said, is not just a recent development.

Certainly not just products but financial services have evolved. In early societies, moneylenders tended to prosper not least due to their ability to judge the personal creditworthiness of a particular project or individual. As society developed, banks filled this role, making a profit from lending, often in different currencies. Provided the currencies could be exchanged for goods and services, and assuming that lending rates were a fair reflection of the risk, these financial services contributed a profit to the institutions and also aided the development of economies and civilisation, facilitating the distribution and free flow of capital.

For many centuries major financial systems were based on metal coins, accounts recorded on paper, and straightforward transactions. At least as far as the overall mechanism was concerned, the system was relatively simple and transparent, though perhaps slower and less efficient than today, when cash is nearly always at hand and transactions flow across the globe. With benefits have come new risks. Thanks to increasingly sophisticated technology, financial transactions are now conducted at extremely high speed. Today a trade can be executed in less than the blink of an eye.* Transaction costs also have fallen radically. The vast increase in global trade and capital flows have also have added a new level of complexity.

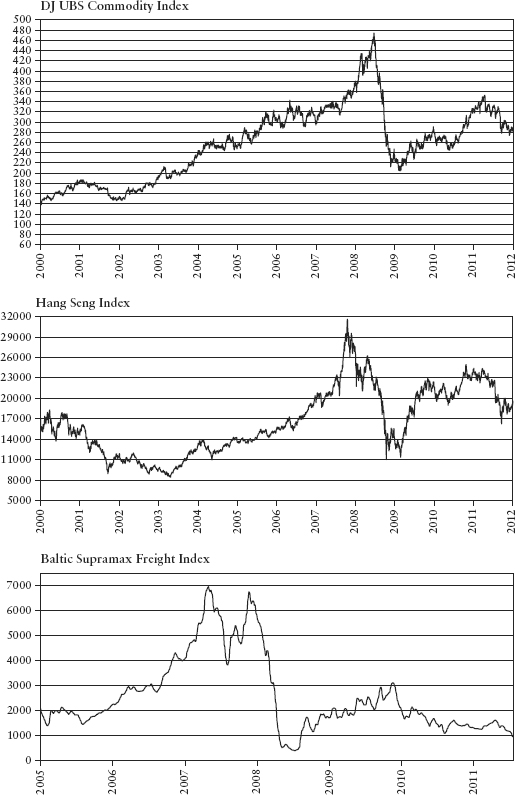

As shown in Figure 6.5, crises are a common feature of markets. What might begin as a good idea catches on and there follows exuberant participation by a widening circle of investors. Wealth becomes concentrated in one asset class until at last the bubble bursts. The speed and magnitude of such events today pose new challenges. What will be the next crisis? It is safe to assume further crises will arise. And in any case, due to the modern high-speed mobility of money and the amounts involved investors also are likely to see much more volatility. Indeed as already suggested by the events of the past decade, volatility is the new “normal.”

As the system has evolved in terms of services, so, too, have financial products increased remarkably in terms of both their widespread use and complexity (see Figure 6.5). Markets during recent years have been flush with liquidity, due in part to leverage in the system and cheap money available. The entire financial system has grown more interconnected with a variety of players, including investment banks, hedge funds, private equity funds, and structured investment vehicles (SIVs). Entities such as hedge funds traditionally have not been subject to the same oversight as banks in their dealings with the general public. These have in the past contributed their own share of shocks to the market.

Part of the crisis that began in 2007 can be explained by highly complex mortgage and asset backed products. For example, securities based on seemingly innocuous household mortgages were “repackaged” and sold without considering the risks of liquidity or market value in the event of an extreme market dislocation. In pursuit of ever-higher returns, increasingly complex financial structures were created, stacking one product atop another. The result was an inherent instability and ignorance of what the real risks were, or even in some instances a cynical disregard for them. A bubble is characterised by a herd mentality. As in a game of financial musical chairs, every player follows the next, each hoping that they, at least, will not be the one left standing when the music stops. All bubbles eventually burst. The one that did so in 2008 left private investors angry and disappointed.

To sum up, the development of financial products might be considered at best to be an evolution and at worst a system of trial and error. On the one hand, financial products are indispensable. Who would like to live in a world with no insurance? Who would prefer to pay cash for a home they purchased? But at the other end of the spectrum, there is always a new product that can be promoted to produce miraculous returns, at least for a limited period of time. Of course, there are no miracles in investing. The financial industry has played a key role in the establishment of modern civilisation, but history and logic show that it is simply not possible to create lasting wealth with no risk, nor without the patience required to obtain deferred rewards. Individuals can get rich quickly if existing wealth is redistributed in a zero-sum financial transaction—for example, buying a winning lottery ticket or inheriting money. Societies as a whole can only increase their total wealth by increasing the value of goods and services. True wealth creation should be a process that benefits greater society, even though it is impossible to say how advances and discoveries ultimately will play out.

All these developments pose numerous challenges for private banking. The recent crisis especially has changed how clients approach investing. Banks, too, must change the way they approach clients. It is no longer enough to offer clients a disjointed selection of products and services. The individual client’s needs and goals must be met by looking at the bigger picture.

ADAPTING TO A CHANGING ENVIRONMENT

How should wealth managers realign their activities to best suit clients’ needs in an environment characterised by a greater mistrust of banks and the products they offer? Clients’ main goals are wealth preservation and real wealth creation. Thus, the industry should start by focusing on “investment solutions” rather than simply pushing numerous unrelated products. To do this, it is useful to approach the discussion by looking at the industry from the point of view of the total offerings to individual clients.

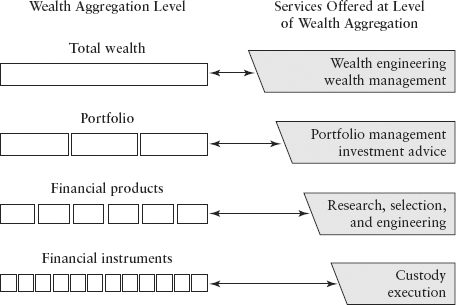

As shown in Figure 6.6, wealth can be thought of in terms of “groupings” or “aggregations.” These are represented in ascending order from the least client-specific types (financial instruments) all the way up to those most directly related to a client (the client’s total wealth). Likewise services can be ranked from the most general, least client-specific such as custody and execution to the most individualised “wealth engineering” and wealth management. Based on this approach, levels of wealth aggregation (left) and services (right) are ranked to correspond according to each level of client individualisation. It is useful for a bank to think along these lines when considering where to put its resources. This perspective is also important for clients, because it represents how the approach might be viewed from the perspective of single clients.

FIGURE 6.6 Aggregation of Wealth from Most Granular (lowest level) to Most Comprehensive (top) and Corresponding Level of Individualisation

Source: Dr. Ulrich Schilling, Employing Multi Agent Systems in the Performance Process of Private Banking Services, Difo-Druck GmbH, Bamberg 2007

Wealth Aggregation

Looking at wealth aggregation as represented in Figure 6.6, one thing becomes clear. There is a progression in terms of “bundling” of wealth of individual clients. At the bottom, on the least client-specific level are financial instruments, which in turn can be combined to make up a financial product. A combination of products and instruments constitutes a portfolio. At the top and most complex level is a client’s total wealth, consisting of a combination of portfolios, along with all other assets and liabilities, such as real estate, mortgages, art, and so forth. As illustrated, at each level there is a corresponding set of services matching the degree of client specificity, ranked from the simplest forms such as custody and execution all the way up to total wealth management. The aim of representing services in this way is to present them as a function of individual client solutions rather than simply as a general array of unrelated products and services. This approach allows a wealth manager to see where the greatest potential lies in terms of adding value to the services offered to individual clients.

The complexity of the wealth groupings depicted in Figure 6.6 increases at each aggregation level. The higher the level of aggregation, the greater the value that can be created for the client. And the more specific the level of aggregation, the closer the bank needs to be to the client to offer these services. In private banking, it is thus important to think of the entire context of an individual client’s needs, as opposed to single products and isolated services. The core value proposition is a tailored, individualised solution. Not only does this approach make more sense for the bank aiming to derive greatest value from the resources devoted to individual clients. For the client as well, his or her genuine needs become readily apparent only when viewed through the lens of this type of “aggregation,” ranked according to how individualised a service or product offering should be.

At the lower levels of aggregation of financial instruments and products, the discussion as far as individual clients are concerned is essentially one involving services that are more or less interchangeable. A given equity, for example, or bond or fund is the same no matter which bank executes the trade. Assuming safe custody, the value of cash or other instruments does not change because of who is holding it. It is worth noting, however, that this is precisely one area where the assumptions usually taken for granted broke down during the 2008 financial crisis. In that period, not even the safety of custody accounts could be taken for granted, as Lehman Brothers’ default illustrated.

Past market shocks highlight that it is key to help clients to establish a truly diversified portfolio. It is thus vital to include in any decisions the client’s total wealth position. A bank must avoid pushing products and adopting a too narrow focus, attempting to capture unrealistic returns that should never have been promised in the first place. With that in mind, the following section examines levels of aggregation. It is followed by a look at services presented in a similar fashion.

At the higher levels of aggregation, there is an almost infinite range of combinations offered to the market in terms of financial products and investment solutions. Navigating this sea requires a clear understanding of the fundamental principles of investment, which first and foremost means there is no ideal product. There is only an optimal match between a particular investor’s investment objectives, risk tolerance, and needs and the investment products—or better, the solutions offered.

Overview of Aggregation Levels

Financial instruments include cash, stocks, bonds, and other assets. Financial products, which tend to be more complex, are an aggregation of financial instruments including an element of service put into some sort of marketable package for distribution purposes. More complex still, a portfolio is a collection of financial instruments and/or financial products managed as a unit. At the highest level of complexity, total wealth refers to the sum of all the assets and portfolios held in all those banks with which the client maintains a relationship. (For information and an overview of the most common types of products and further information on selecting funds, please refer to Appendices 1 and 2 at the end of this chapter.)

- Financial instruments

Cash, evidence of ownership of an asset or entity, or the contractual rights to deliver or receive an asset of some sort are traditionally thought of as financial instruments. Based on that definition, this category includes the most basic units of wealth, such as cash and currencies along with stocks, bonds, and derivatives such as options, forward contracts, and futures.

- Financial products

Financial products represent a higher level of wealth aggregation, consisting of financial instruments bundled together with an element of service into marketable packages for distribution purposes. These are the main categories of financial products and include mutual funds and other investment products. This category also includes hedge funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), funds of funds, and structured products.

- Portfolio

A portfolio is a collection of financial instruments and financial products that are managed as a unit. At the financial instruments and products aggregation level, the focus is on the characteristics of a particular asset. But at this level the main focus, rather than being on individual instruments, is on how these work in combination, and how they interact in terms of their risk/return characteristics and cash flows.The previous chapter discussed the increased sophistication and the active role taken by clients in managing wealth, requiring a comprehensive approach to advice. Portfolio-level advice is growing more important due to the general volatility and complexity of today’s financial markets. Regarding portfolios, the better a client’s overall investments or assets and liabilities can be pictured as a unit, the more comprehensive the approach that can be taken in advising the client on how to reach or achieve the long-term goals, while taking into account the individual’s short-term constraints.

- Total wealth

HNWIs often have a number of different portfolios that are overseen by different wealth managers. Rarely will a client entrust his or her total wealth to a single bank or RM. However, it is still possible to discuss “total” wealth management when the client involves the RM in matters that extend beyond a single financial portfolio to include different types of assets held in different jurisdictions. A client may have primary and secondary residences, land, or businesses. These holdings may be subject to a range of different tax and regulatory regimes. At the total wealth level, the goal is to optimise all these holdings to offer the client the best overall solution. This means addressing questions of wealth protection and capital appreciation, as well as financial planning, retirement, succession, and philanthropy.

Summary of Aggregation Levels

To sum up, it is important to regard the particular products and services offered to clients not as single, unrelated units. Instead they are parts of a bigger picture. Taking this approach means that the client has the benefit of getting more than just an offering that is a sum of separate parts. Individual products that may not be right in terms of the overall needs can be avoided.

Not only is it important to view an individual client’s wealth from the aggregate side, ranging from the most granular type of products and instruments all the way up to the broadest level of total wealth. The services applied at each level also play a key role.

Wealth Services

As already noted, private banking services can be divided into two categories—those that are not individualised and those that apply in a specific way to individual clients. Those services that are not client specific, meaning those that are conducted in most cases without reference to any particular client and may be considered in some ways as commodities, pertain to a broad class of individuals with little modification no matter which client is involved. As wealth is increasingly aggregated, the focus becomes ever more a function of an individual client’s personal needs. Like products, services can be depicted in terms of client specificity, ranging from least to most individualised. This relates to how customised they are with regard to an individual client.

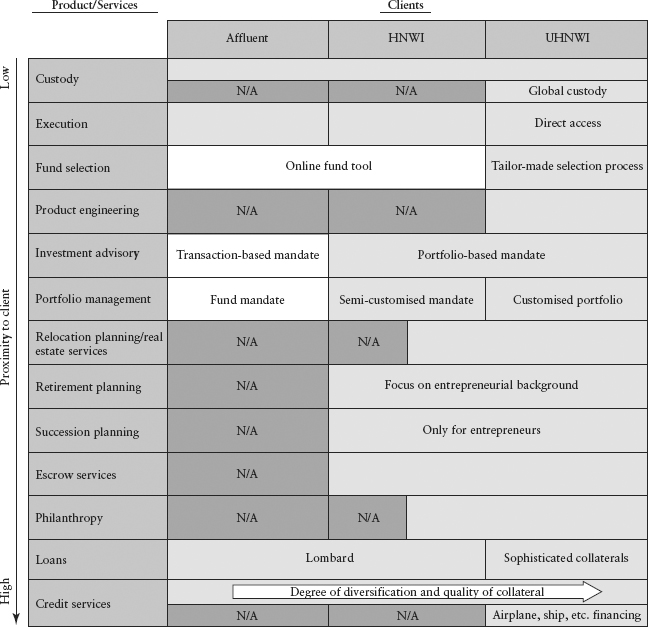

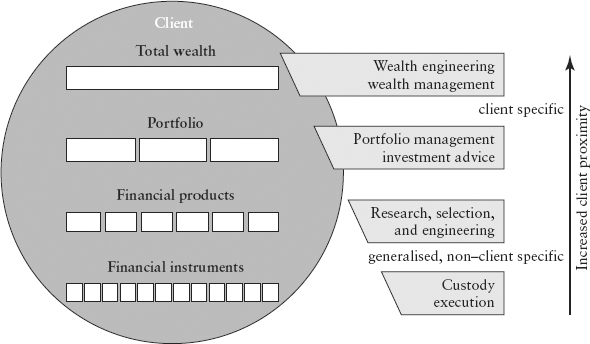

At the top of the scale are those central value propositions offered by private banks to serve clients’ unique needs, services that directly touch the client. To illustrate this, Figure 6.7 depicts the same overview as Figure 6.6, but this time with the client added to the picture. It is now clear which services are closest to the client. As shown in the chart, for each service level there is a corresponding level of wealth “aggregation.” At the lowest level, the least complex aggregations (financial instruments) correspond to the least client-specific services (custody, execution). As the complexity increases, the service becomes more individualised and client specific. Looking at products and services in such manner allows a bank to serve a client in an individualised and comprehensive way. It also allows the client to receive a tailored and “bespoke” solution. For clients it is important to note, however, that not all services are available for each wealth category.*

FIGURE 6.7 Some Services Have a Direct Relation to Individual Clients, Whereas Others Are Less Client Specific

Source: Dr. Ulrich Schilling, Employing Multi Agent Systems in the Performance Process of Private Banking Services, Difo-Druck GmbH, Bamberg 2007

Overview of Service Levels

Because services can be classified according to the wealth aggregation level that they target, it is possible to arrange these on a scale from least to most individualised. On the least individualised level, services for financial instruments involve mainly custody and execution. On a somewhat higher level (because financial products are tailored more specifically to clients), this category includes research, selection, and specific solutions incorporating structuring of particular products. Moving still higher, at the portfolio level, services become more tailored to individual clients. When total wealth is taken into account, the focus is even more client specific. Here wealth engineering and wealth management expertise and services come into discussion.

Some services could be outsourced. For example, because custody and execution are usually not targeted to individual clients, the bank could outsource them. Portfolio management and investment advice, however, including fund and product selection, wealth engineering, and investment management, are more client specific. A private bank has to excel in these. They are the services that create the most value for the client and consequently also for the bank.

The following presents a description of those services that are common in private banking, ranging from the least client specific to those that are very specific, tailored to a single individual.

Custody and Execution

Custody and execution are not tailored to individuals per se, and there is little opportunity in these areas to add client-specific value. While services at this level are highly important and must meet exacting standards, they are basically the same wherever they are done and are not directly influenced by geography. These services must be excellent and exacting, but they are not very close to the individual client, nor are there many insights to be derived as to how these can enhance individual client satisfaction, apart from ensuring zero tolerance for error. Any mistakes in this area (for example, the wrong figure entered in a trade) can turn out to be extremely costly for a bank.

- Custody

Custody services refer to the safekeeping of assets such as equities and bonds and the related administrative procedures. Besides buying and selling assets, the custodian needs to monitor and collect payments of interest, dividends, and coupons, while keeping the client informed of the rights and responsibilities associated with holding these assets, including proxy voting done on the client’s behalf at shareholders’ meetings. There may be a need to manage currency transactions.

- Execution

Execution is the process of completing an order to buy or sell a financial instrument. When offered as a standalone service, it refers to any type of financial transaction that does not fall into a custody agreement. The European Union’s Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID), introduced in the Chapter 4, “Forces Shaping the Regulatory Environment,” requires that a firm take all possible steps to ensure the best execution of a client’s orders. Best execution means more than simply obtaining a price in a transaction; it encompasses the choice of an execution channel that offers the best combination of price, speed, likelihood of execution, and likelihood of settlement.

Research, Selection, and Product Engineering

The level of aggregation represented by research, selection, and product engineering is one step closer to the client than the services just described. It thus offers slightly more potential to add value. It is still quite possible to engineer and select best-in-class products here, as well, without targeting any specific client in order to draw up a short list of investment recommendations.

- Research

Banks usually have a research department to comment on different asset classes, and provide buy and sell recommendations as well as insight on macroeconomic developments. The information will be presented to clients, usually by the relationship manager. This area also includes so-called groundwork research that may or may not lead to new intellectual property, ideas, or methods. It also encompasses market research that serves as the basis for investment decisions and strategy.

- Selection

This process includes fund selection. General guidelines might be applied here, governing, for example, how large a fund should be (e.g., at least more than $100 million in assets). The fund should have an established track record (more than three years tends to be a standard minimum). Performance should meet a certain level (such as top quartile of the relevant peer group). Further information on the process used to select individual funds can be found in Appendix 2 at the end of this chapter.

- Product engineering and financial engineering

Financial products usually are simply aggregations of instruments. This means that there is a relatively low barrier of entry in this field, and the number of new structured products that can be created can easily outstrip the number of clients in a given bank or institution to buy them. Product engineering or structuring is the process of combining financial instruments and services to create a product with a particular benefit. If it is a one-off combination, it can be described as a “tailored solution.”

Portfolio Management and Investment Advice

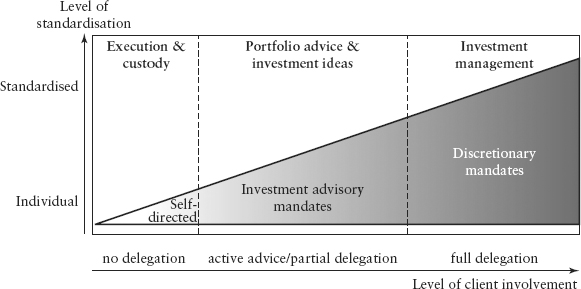

Some services such as custody and execution, as well as research, can be treated as standardised processes that are not generally tailored to fit specific clients. Moving higher up the chain toward more client-specific functions, it becomes increasingly important to keep all aspects of an individual client’s situation in mind. This includes the client’s objectives and goals. In this category services start to be considered client specific and are directly linked to the individual client. As shown in Figure 6.8, they include both managing portfolios and offering investment advice.

FIGURE 6.8 The Most Self-Directed Clients Typically Rely on Standardised Products and Services, Whereas Clients Delegating Investment Responsibility Require a More Individualised Approach

Source: Julius Baer

These categories can be further delineated. Where portfolio advice is concerned, the level of client involvement goes from discretionary mandates, where clients are least involved in the process, to the advisory services, in which clients receive advice but take an active role themselves in the investment decision-making process (see Figure 6.8). The level at which the client is most involved is termed “self-directed.” Clients in this category are not actively advised by the bank and make their own investment decisions. They rely on the bank primarily for execution and custody services. The categories are described in detail here in Figure 6.8.

- Discretionary mandates

Under a discretionary mandate, the client authorises the bank to make day-to-day investment decisions within the context of an agreed-on risk tolerance and investment strategy framework. The bank is contractually authorised by the client to make transactions in the client’s name and on the client’s account. The strategy and performance are periodically reviewed with the client and necessary changes are implemented. Investment decision making is fully delegated to the bank.

- Transaction- and portfolio-based advisory services

A distinction can be made between transaction- and portfolio-based advisory services. In the case of transaction-based advisory services, the investment advice is designed to allow the client to exploit short-term opportunities in the market by suggesting investment ideas based on the bank’s market outlook, while recommending the appropriate stop-loss levels. Portfolio advisory services and mandates are for clients pursuing a structured investment process. Portfolio advisory mandates differ from discretionary mandates in that while portfolio advisory services are provided, the client makes the ultimate decisions on transactions. However, the client’s needs, time horizon, risk tolerance, and performance expectations are analysed the same way as in the discretionary mandate framework.

- Self-directed clients

These clients usually make their own decisions without delegating any tasks regarding financial investments to the bank. They have a dedicated relationship manager. The bank provides execution and safekeeping of securities and performs the reporting on all accounts and securities as well as an overview of asset allocations and a performance analysis. The bank provides research and investment ideas to the client but offers no investment advice or investment recommendations.

Wealth Engineering and Management

Wealth engineering and wealth management are the services that take a bank closest to the client. These services require an in-depth relationship and are where most value can be added for clients. Therefore, every relationship manager should aspire to win the client’s confidence through successful investment advice and high-quality services, not only to ensure a successful result but to ensure greater opportunity to be entrusted with matters pertaining to total wealth management.

Wealth engineering and management involves the comprehensive analysis of a client’s needs to enhance all dimensions of the client’s total wealth. Services in this category include, for example, offering clients assistance when relocating and/or buying and selling property, planning for retirement and inheritance planning, escrow services, philanthropy, and offering clients credit. Some of the most common examples are described as follows:

- Real estate services and relocation planning

There are two types of investments in real estate: clients may wish to buy or sell their own residences, or they may also purchase property purely as an investment. Apart from regulatory aspects, such as whether a foreign national can purchase real estate without a specific permit, transactions may have tax implications. A bank might help clients to find property and serve as a discreet intermediary in real estate transactions. A banker might also know the local market better than the client.Relocation planning services (finding property, getting permits, insurance, coordinating the move) also can assist clients to gain a clear idea about their goals and options in order to maximise the benefits of a relocation move. Real estate services focus on all aspects of owning or investing in residential or commercial property. While it may make more sense for the bank to outsource real estate services to specialists, the emotional link between a client and his or her primary residence or residences is strong, which makes it a good idea for an RM to be in position, as needed, to offer competent advice and solid solutions in this area.

- Retirement planning

Retirement planning for HNWIs can be complex. Very often, wealthy clients have real estate in various countries, and they often have cash flow needs in a variety of currencies; their cash needs tend to be large. Wealthy retired clients need an active asset/liability management, structuring their assets to generate cash flow to meet liabilities without eroding their asset base. Common to all clients is the need to establish low-risk investments that generate sufficient income to cover their expenditures during the portion of their lives in which income from daily work typically declines.

- Succession planning and will execution

Wills and testaments take the bank into strongly emotional territory. Succession planning aims to reconcile an individual’s wishes regarding the estate with the needs and general circumstances of the heirs. Making matters more complicated, HNWIs often have assets in different countries, and their designated successors may be living in different jurisdictions, too. The fact that more than one country is involved might mean higher costs (e.g., due to taxation), and may require more time-consuming transactions allowing for transfer of legal ownership and control of assets.When a relative has passed away, clients feel understandably vulnerable. A relationship manager’s ability to offer sound advice and support during the period of the execution of a will, done sensibly and judiciously, can build strong bonds and bridges to the heirs. It also becomes a matter of practicality, providing the relationship manager truly has a trusted advisor role and is familiar with the financial complexity involving an individual client.

- Philanthropy

Philanthropy services involve all types of advice related to planned giving, including establishing and managing private foundations and charitable trusts. Philanthropy has long been a popular service for ultra-high-net-worth individuals (UHNWIs). But it is gaining ground in lower wealth brackets as well, as banks seek to expand comprehensive service offerings to differentiate themselves from the competition.

- Credit services

Credits, loans, or mortgages can be considered products. The actual process of approving credit, however, especially when the loan is made against assets owned by the client and held by the bank is essentially a service. Such loans are often known as Lombard loans when made against marketable securities or bonds. These loans require an increasingly sophisticated credit department, given that banks look to expand the universe of acceptable collateral.“Lending establishes trust and a sense of partnership, potentially the single most important factor in client satisfaction,” according to a study by Oliver Wyman.(3) Wealth managers can generate a significant portion of revenue from lending, but based on this report, not all of them make use of it to full potential. According to Oliver Wyman, “big banks typically are most willing to lend, leveraging their balance sheets, captive funding bases and risk management expertise. Pure private banks and investment banks tend to lend less and in some cases not at all. It adds that “these players should reconsider lending.” Besides bringing in additional interest income, lending can be a powerful form of client bonding. It can also reduce asset defections, (e.g., in cases where a client might otherwise opt to withdraw and liquidate assets to cover cash flow needs). When a portion of the client’s portfolio is the collateral for the loan, there is a significant inducement to stay with a bank.

Summary of Wealth Services

Services can be non–client specific, or more specifically tailored to meet individual clients’ needs. A private bank must excel both in client-specific services (e.g., portfolio management and investment advice, wealth engineering and management) as well as in the areas that are by their nature not tailored to individual clients (e.g., custody and transaction services). Given that these “non-specific” services must be excellent in any case but are typically largely anonymous and interchangeable, the greatest additional benefit to a private bank can be derived by focusing on client-specific services. In this regard the advisory process matches products to clients’ needs. Some private banks have branded advisory processes, which are designed to heighten client involvement in the advisory process through explicit structuring of the process. The next portion of this chapter discusses how to best match client needs with the products and services provided by the bank.

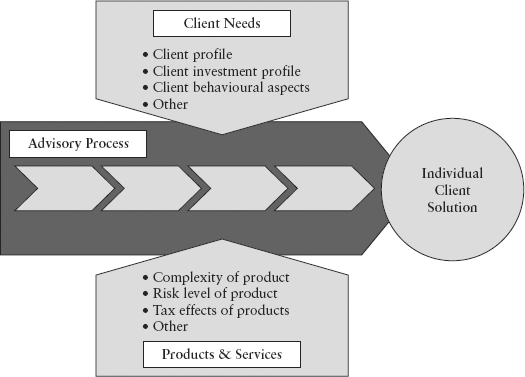

MATCHING CLIENT NEEDS TO PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

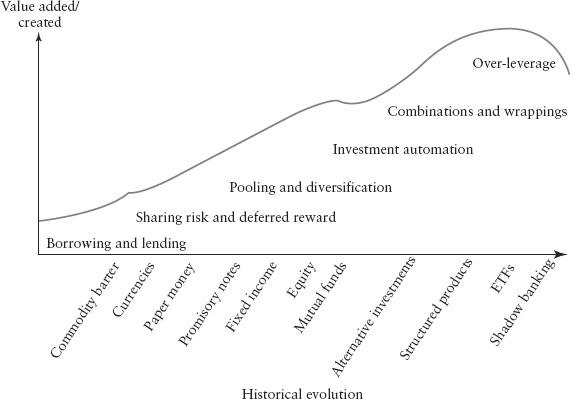

The advisory process provides the ultimate link between clients on the one hand and investment solutions on the other (see Figure 6.9). Advisory services are thus a critical part of the overall picture. For clients, even those who are self-directed and manage their assets by themselves, having a good advisory service is important. For discretionary clients relying on the bank to choose products and services, getting it right is essential. Structured advisory processes are important tools for improving client experience and service excellence. They help to ensure regulatory compliance. For banks, advisory processes also serve an important role. They strengthen the bonds between the client and the brand. The advisory process puts the focus on the entire bank (as well as the brand) as opposed to simply highlighting the efforts of a single relationship manager.

FIGURE 6.9 The Advisory Process Is the Essential Link between Client Needs and Products and Services

Source: Author

The Advisory Process

The steps in an advisory process generally begin by getting to know the client, understanding his or her individual objectives, needs, and risk profile, as well as dealing with numerous other factors that will determine how the person makes decisions, communicates, and responds. This is an ongoing task that will evolve over the life of the relationship and ensures that the process is truly a personal one. Understanding the client’s particular problems and goals constitute the next key step in the relationship. These could include new family situations such as marriage or divorce, inheritance issues, changing financial situations tied to selling property or a company, or any other factor that could affect investment decisions. As this process is also likely to be continued over the entire relationship, communication channels must be kept open. In addition, clients need to be kept informed of their options relating to their particular situation, evaluating these as necessary. The client can then make the best decision suited to his or her particular situation.

A good advisory process includes regular feedback to evaluate the results of the decisions. An example of such an advisory process is shown in Figure 6.10.

Which products meet the needs of which client segment? This is very much a function of the requirements of the individual client and his or her stage in life, as well as numerous other factors ranging from the client’s approach to risk and risk tolerance, age, cash flow needs, future liabilities, level of wealth, domicile, and so forth.

Figure 6.11 offers a simplified overview to determine which individual offerings are best suited to a particular client group or a single client, drawing them from the full product range. In each case, the relationship manager together with the advisory process provides the crucial link in the process, bringing together clients with products and services. Using as a guide a format such as the one depicted, a bank can train relationship managers to provide a standardised advisory approach. Ultimately, however, it comes down to each relationship manager to deliver a service unique to the individual client at any given moment in time. The process must be continuously adapted given that both markets and individual clients’ needs change.

CONCLUSION

One significant change affecting the industry has been the strong growth in the number of financial products and services available to investors. Not only have these products increased in number, they have grown in complexity. At the same time, clients, especially in light of the losses suffered during the financial crisis, require a comprehensive approach to wealth management. The developments affecting clients, market disruptions, and growing complexity, along with changes in the legal environment, are forcing banks to think carefully about their focus. The future belongs to banks that can position themselves by having a sophisticated advisory process in place, which allows the particular client’s needs and goals to be translated into a tailor-made, compliant investment solution. Transparency will be a top priority, driven by increasing regulatory pressure.

The range of products and services has increased partly as a result of declines in transaction costs. This was possible due to advances in technology, which enabled more and more niche products to be created and distributed globally at very low cost. At the same time, the trend toward increased bundling has created a layer of opacity that can ultimately lead to inadequate risk management and was a major factor in giving rise to problems that led to the financial crisis that peaked in 2008. In response to such trends, private banks increasingly are seeking transparent and secure ways to improve the risk/return profile of the products they offer. Furthermore, more regulatory pressure means that banks will have to address the issue of advisory liability, which in future could become a greater business risk. The legal obligations arising from the client relationship will become an increasingly important aspect when it comes to organising the wealth management business. The level of advice given to the client in each case will be governed by a service agreement or umbrella contract. This will in many ways be considerably different from the general terms and conditions used by banks today.

The burden will be on banks to clarify the client’s risk tolerance and ability more thoroughly, based on a carefully structured advisory process. Custody agreements will be available for self-directed clients. In these cases the bank will provide current accounts and a securities depot. The rest will be up to the client. The bank will most likely give no investment advice and make no recommendations and will thus not assume any liability.

In advisory relationships the bank will give portfolio and investment advice via structured advisory processes. In the future, as regulators increasingly consider it the duty of the bank to protect the client, advisory or semi-advisory umbrella contracts will appear that clearly define the limits of the liability of the bank when giving investment advice.

Finally, there are discretionary mandates where the client delegates the selection and final decision regarding investment choices to the bank. Discretionary mandates are likely to become more aligned with the client’s goals. Going forward, it is probable that the industry will see more diversified and robust portfolios that employ a more active asset allocation together with an active risk management layer to ensure long-term capital preservation. Furthermore, some banks will adopt a more goal-oriented approach to solutions encompassing an active asset/liability management for wealthy clients.

NOTES

1. Ferguson, N. 2002. Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World. Allen Lane/Penguin Press.

2. Ferguson, N. 2008. The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World. Penguin Press.

3. Oliver Wyman. 2008. “The Future of Private Banking: A Wealth of Opportunity.”

APPENDIX 1: OVERVIEW OF THE MOST COMMON FINANCIAL PRODUCTS

Financial products take into account instruments including those described herein that have been combined to meet certain goals. These can make it easier to invest, but here it is important that all parties involved understand the products before buying or selling them.

Basic Products

Even some of the simplest forms of financial products can be considered as “aggregates” or “packages” that can be applied to make them more practical and assist in marketing. Aggregating or packaging describes how various financial components are combined to produce a single product—for example, a deposit account combines different elements: cash, payment of a fixed interest rate, certain fees and charges, and legal rights and privileges.

Funds and Related Investment Products—An Overview

Funds, as a general class, pool the assets of many investors to achieve the principal aims of diversification and economies of scale. The cost of research and management overheads can thus be spread across a greater number of investors, and individuals gain access to investment opportunities and expertise that they might not otherwise be able to obtain. Funds differ mainly in terms of the access rules—public or private, the minimum investment, the regulatory framework, and the investment strategy (style, sector, region, asset class, etc.).

Mutual Funds

A mutual fund is a company that sells shares in its own stock to the public and uses the investments to pursue a particular investment strategy by buying equities, bonds, money market instruments, and so forth. Mutual fund shares can be traded, and the value varies with the performance of the fund. Mutual funds offer the advantages of convenience, diversification, and professional management, most often with a low minimum investment level.

ETFs, ETNs, and other Exchange-Traded Vehicles

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are investment vehicles that are traded on stock exchanges like equities. They are designed to track the performance of a particular index or basket of instruments. ETFs are usually considered passive investments, which makes them cheaper than mutual funds to manage. While fees associated with these instruments are lower than mutual funds, investors who trade ETFs actively must figure in trading costs. Besides ETFs, there are exchange-traded notes (ETNs), which resemble ETFs but pay returns in a fashion similar to bonds, and exchange-traded commodities (ETCs) that track commodities prices.

Hedge Funds

Hedge funds are sophisticated funds that are permitted to engage in a wider range of investment and trading activities than mutual funds. They are known for using strategies intended to make money under different market conditions, including down markets, and for using methods that might be employed to enhance returns, sometimes also taking unconventional risks.

Hedge funds are usually limited partnerships with the manager as a general partner and the investors taking limited partnerships. Fees are performance related; hedge funds may charge a management fee of around 2 percent and a performance fee of typically 20 percent. Access is limited to certain types of investors, generally those who have experience in financial products and a certain amount of wealth. There are often restrictions on the entry and exit periods. Because they typically enjoy more freedom and less regulator scrutiny, these funds may be barred from publicly advertising their products. In the European Union, a new version of existing rules has been introduced, for the first time enabling hedge funds to set up so-called UCITS-compliant structures, allowing them to market certain products to a broader public. Under the latest version of the rules, the so-called Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) funds can, for example, invest in derivatives, making it easier for hedge funds to offer UCITS-type funds. As a result, some hedge funds based outside of the EU are repackaging versions of their funds to meet the guidelines. These variations can be marketed to a broader audience within the EU. But by joining the already significant volume of UCITS funds, hedge funds must ensure that these products meet strict guidelines covering, among other things, structure, management, and documentation, as well as what funds can and cannot invest in. They also must work to generate competitive returns.

Funds of Funds

A fund of fund is any type of fund whose strategy is to invest in other funds, as opposed to investing directly in financial instruments. While funds of funds promise increased diversification, they are considered more expensive because of the various layers of fees. Furthermore, when used as components of a wealth portfolio they may lack transparency, making it harder to know exactly how diversified a portfolio containing several different products might truly be.

Private Equity

Private equity refers to investments in firms that have not yet listed on the stock exchange. Investments in private equity are usually therefore highly illiquid. Private equity investors hope for large gains when the company they invest in is sold to another company or when the company lists its shares on the stock exchange.

Structured Products

Structured products are prepackaged investment strategies in the form of investment vehicles issued mainly by banks. They can be used for capital protection, diversification, or risk management, although usually there is no guarantee on such products. They may provide yield enhancement, allow participation in market trends, and satisfy a desire to obtain leverage (i.e., aiming to get a higher return for the same amount of investment).

APPENDIX 2: KEY CRITERIA IN THE SELECTION OF FUNDS AND FUNDS OF FUNDS

Funds are a form of aggregation that makes it easier for investors to diversify their investments. It is important to note that the universe of funds is vast, and finding the right fund to suit an investor’s needs is an integral part of the process.

Rating

The first step in fund selection is classification to rate funds. Funds need to be classified into categories based on organisational aspects of the particular company managing the product, the investment approach taken, the currency of the fund or share class, length of the track record, and historical performance. Within each class, funds are identified within their category relative to peers based on a variety of factors, including how the fund is organised, the investment process, the managers, and the fund’s historical performance.

Organisation

It is important to know how the firm managing the fund is organised, its long-term viability with regard to retaining management talent and sustaining business activities. People who are good at selecting funds do more than read published reports and brochures. They visit the fund managers and talk to them directly to assess the firm’s culture, management incentives, and regulatory and compliance arrangements.

Investment Process

This needs to be well defined and consistently applied. The fund selector will look for competitive advantages at the process level, such as unique modelling capabilities or unusual perspectives or depth of analytical resources. The investment process also should offer an indication of whether the fund’s premises that determined historical performance are still valid. While it is impossible to predict a fund’s future performance, management fees are a known quantity that can be minimised if two similar propositions are being considered. Besides the management expense ratio, the fund’s pattern of trading expenses can affect overall performance.

Investment Professionals, Fund Managers

Those overseeing the fund need to be experienced in the fund’s mandate or strategy, and within the team, there needs to be a pool of significant experience. The team should possess complementary skills and enough personnel to ensure that the fund managers are not distracted by other mandates, including sales or client responsibilities. While the management track record is no guarantee of future performance, a consistent performance over at least three to five years and a consistent strategy are favourable indications for the future.

Historical Performance

The performance is compared to a benchmark, often based on an index that includes the same exposures as the fund’s investments or on a reference interest rate. Performance can also be judged relative to peers. It is important to study risk-adjusted performance and to look at a time frame sufficient to truly judge performance—for example, three to five years. Finally, one needs to look at the factors to which performance is attributed and apply plausibility tests. In other words, there has to be a plausible correlation between any performance in excess of the market, volatility, and the purported strengths of the investment managers.

*I asked Guido Ruoss to contribute this chapter due to his special expertise and knowledge in these areas as Head of Business & Product Management of the Investment Solutions Group at Bank Julius Baer. Second and even more important to me is our shared belief that innovative and client-centric products and services form an integral part of a modern private bank offering. Author.

*According to an article published in the Financial Times, the pace of execution of orders on exchanges has gone from seconds, to milliseconds, to microseconds, and even to nanoseconds. Feb 24 2011, Financial Times: “Trading Monitoring Goes into Nanoseconds.”

*For a detailed overview, refer to Figure 6.11.