Chapter 4

Forces Shaping the Regulatory Environment

Regulatory developments cannot be thought of as something happening separately from the “real” world. They are very much a part of banking and one of the major factors affecting the industry. For private banking, there are two main issues likely to have the biggest impact in the foreseeable future: tax compliance and discussions about consumer protection.

Looking at the first of these, a transition to full tax compliance for all clients must be part of the strategy of any serious private bank. This marks a break with the mindset of the past. We are moving toward a new private banking paradigm.

Apart from the tax environment, consumer protection, driven by regulations, such as MiFID in Europe, are having a major impact as well. Consumer protection laws are aimed at increasing transparency and accountability. It is becoming extremely important to match the product to the profile of the client.

A further trend that is having a major influence on private banking is growing activity in mergers and acquisitions. This is being led in part by the need for consolidation to address rising costs. Understanding all of these aspects will be key in terms of positioning and defining the role of financial services organisations.

This chapter presents an overview of some of the major points and developments that are especially relevant in this regard for private banks from a Swiss perspective.

THE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

The regulatory environment has a major impact on banking. This was always the case, but it has become quite evident in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Although it is difficult to predict how the situation will look in the coming years, nearly all indications are that regulations will be stricter and play a significant role in how the business develops. The forces at work shaping the industry include both those within national boundaries and global efforts to make the financial system less prone to systemic risks.

International vs. National Interests

Every country with a banking industry wants to secure returns from financial services. It is an industry that offers a good source of tax revenue and provides a significant number of jobs. Switzerland, with its long history of private banking, is no exception. Amid a growing number of rules dictated by global concerns, Switzerland’s approach has increasingly shifted toward one of international cooperation.

Swiss banks’ discretion is older than the modern Swiss state. Starting in the 17th century, an increasingly powerful French monarchy depended on borrowing to maintain not only extravagances (e.g., Versailles) but also a standing army. It turned to Swiss-based bankers. These included not just Swiss, but also some former French citizens, Protestants who had been forced to flee France. Reflecting the growth in the business, in 1713, the Great Council of Geneva called for bankers to keep client registers, while prohibiting bankers from disclosing their clients’ names unless authorised. The French Revolution in 1789 created more demand for Swiss banking services as titled gentry sought a safe place to keep their wealth.

Through the 19th century, Swiss banks flourished. Switzerland’s Constitution, adopted in 1848, led to a more centralised government and ensured political stability. A wealthy class of industrialists had sprung up in Europe, helping to drive demand for banks serving individual families. But following the 1929 stock market crash and during the subsequent economic depression, banks, including those in Switzerland, faced tough times. In 1931, Germany intensified exchange controls, and in 1933, the Swiss government was forced to bail out a bank that had nearly gone bankrupt when the Nazi government blocked repayments of foreign loans. France was also putting pressure on the Swiss, claiming legal authority over French accounts abroad. Amid efforts to tighten banking regulations, the Federal Act on Banks and Savings Banks was passed in 1934. Article 47 of the Act threatens fines and/or imprisonment for people who disclose information learned as an employee at a bank.

In 1984, the Swiss people voted in a public referendum against loosening bank secrecy by a 73 percent majority. At the same time, the Swiss government’s desire for good relations with the European Union and the need to be seen to be proactive in the fight against money laundering and organised crime has led to changes through the years that make it easier for banks to provide information about accounts deemed to be criminal. Meanwhile, the net has tightened on criminal money, as both international and Swiss anti–money laundering efforts brought pressure to bear.

Coinciding with the global financial crisis, scrutiny on Switzerland and other centres managing offshore wealth has increased. Governments facing high costs to bail out banks in their home countries and restore fiscal stability are in no mood to tolerate tax evasion. While Swiss regulations still ensure secrecy, the onerous reporting requirements placed on account holders that are US or European Union (EU) member state taxpayers has created heavy demands on banks in terms of client reporting. Unlike foreigners whose main focus in having a Swiss account was for purposes of privacy protection, a person with an account in Switzerland today is more likely looking for higher quality services, while taking into consideration the regulatory environment of his or her country of residence. Thus, they are likely to be demanding and sophisticated clients. These clients choose their bank based on quality and expertise, not on bank secrecy.

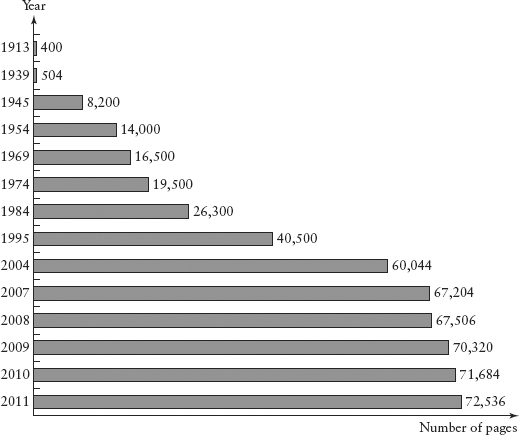

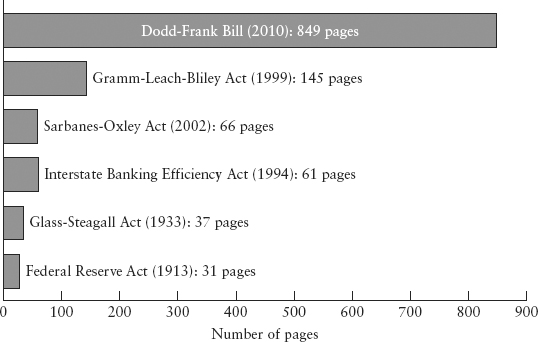

Tax compliancy is getting ever more difficult. Tax law is becoming an increasingly weighty matter—literally. Figure 4.1 shows the number of pages in published US tax law. These increased to over 72,000 in 2011 from 400 in 1913. Not just tax legislation but financial laws are becoming more voluminous. As shown in Figure 4.2, the number of pages in some key US legislation governing financial firms also has increased. The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 was just 31 pages long. By contrast, the draft Dodd-Frank Bill dating from 2010 was a whopping 2,319 pages long. The final version was cut down slightly to “only” 849 pages.

FIGURE 4.1 Increase in Pages Contained in US Federal Tax Law, illustrated by Pages in the CCH Standard Federal Tax Reporter: from 400 in 1913 to 72,536 in 2011

Sources: © 2012, CCH INCORPORATED. All Rights Reserved

FIGURE 4.2 Increase in Pages of US Bank Legislation

Source: Mark J. Perry, University of Michigan. 2010

A growing complexity in the rules is just part of what banks must deal with. They must also understand changes in the environment and how these are affecting clients and clients’ businesses. The EU Savings Tax Directive came into force among EU members in 2005 to ensure uniform information sharing for tax purposes among all EU member states. The taxes are applied to cross-border savings income (for example, interest on bank deposits including savings accounts, interest from bonds and income from investment funds). Following bilateral discussions with the EU, Switzerland signed similar rules that came into force in 2005. These allow a choice. Clients can either authorise the bank to share information about their accounts directly with tax authorities, or banks may directly deduct a “tax retention” from clients based on savings income, without revealing the clients’ identity. The tax rate has been increased in stages to 35 percent of income on interest. However, since the EU aims to have an automatic exchange of information system only, separate bilateral agreements reached but not yet ratified with the UK, Austria, and Germany foresee an “equivalent” framework but still granting a certain level of privacy protection. (For further information see also the Appendix at the end of this chapter.)

Not only are rules pertaining to customers being tightened. Bank capital standards are in the process of an overhaul, which includes raising banks’ capital requirements. Banks automatically set aside capital to cover risks related to lending or other activities and to general exposure. Global standards were introduced in the late 1980s. The first set of rules relied on a simple formula to assess the capital needed to cover “risk-weighted” assets (i.e., the level of risk calculated for a particular borrower). These rules were collectively called the Basel Accord, after the town where the Basel Committee that drafted the rules is located. The original version of the Accord, adopted in 1988, was straightforward. This was an advantage. But these rules were soon considered to be too broad, and by the 1990s, they were deemed no longer adequate. For example, under the old rules, bonds issued by a sovereign government in the bank’s domestic currency were treated as effectively “riskless”—banks did not have to set aside extra capital for such lending. Such an approach today would be unthinkable. New versions of the Basel agreement have been drafted and adopted. The latest is Basel III. It will be phased in gradually by 2019. It requires many banks to raise capital and could force some to scale back or divest some businesses.

In addition to capital rules, there has been much discussion regarding proposals to tighten restrictions on banking activities, including calls among some experts and politicians to reinstate aspects of the US Glass-Steagall Act. Passed by Congress in 1933, the Act prohibited commercial banks from engaging in investment banking and related businesses. This was designed as a safeguard to protect investors following bank failures after the stock market crash of 1929. In 1999, due to belief that Glass-Steagall was outdated, a new US law, the Financial Modernization Act (commonly known as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act) broke down the barriers that Glass-Steagall had erected. The new law merely acknowledged what already had been tacitly accepted. Bank holding companies in the United States were already engaging in securities underwriting, even before the law was set aside. Conglomerates active in banking could own securities affiliates that generated a substantial amount of revenue by, for example, underwriting bond issuance. Ending the Glass-Steagall–type separation reflected what had become in reality common practice. In retrospect, it is easy to ask whether allowing commercial lenders to buy and sell sophisticated derivatives was such a good idea. The calls to reinstate some kind of separation between investment banks and deposit-taking banks—a new Glass-Steagall—are continuing, including in Europe. Banks deemed “too big to fail” are the focus of such discussions. Whether separating these institutions into smaller, independent units could help to mitigate risks posed to investors and ultimately to governments should a major banking group fail is one consideration driving these discussions.

Pure-play private banks are generally in a better position in this regard, given that theirs is a business that does not require large amounts of capital to cover risks. Private banks’ loans to clients usually are secured by clients’ assets. Trading for the bank’s own account (proprietary trading) is not common practice among wealth managers. While financial assets lose value in times of market stress, clients of private banks still pay fees for services that provide a relatively steady stream of revenue, while investment banks’ earnings tend to be much more volatile. Even so, stricter rules along with pressure from investors are leading many banks to review their business models. The rationale in the 1990s and the early part of the present century favouring ever-bigger financial conglomerates has started to look less appealing. A paring down of these firms could provide opportunities for private banks. As larger groups with different businesses under one roof split wealth management and investment banking, choosing to focus on one or the other business, the landscape for private banking is changing, too. Freeing up existing operations, creating new ones, and reorganising old companies will offer both opportunities and new concerns to existing private banks. This could reduce the number of players in some private banking markets. It also could create opportunities for mergers and acquisitions among independent private banks and those spun off from bigger institutions.

Waves of Regulatory Pressure

It is possible to think in terms of waves of regulation—a phase of more restrictive rules followed by deregulation. Then a crisis ensues and brings the next round of regulation. Finding innovative solutions in business is often a positive endeavour. But developing financial products and services aimed mainly at circumventing existing rules to make money for the industry provider can bring not only risks to consumers but the risk that too many participants join the trend, reasoning that “everybody’s doing it.” As more players join, fearing their competitive position will suffer otherwise, destabilisation follows. A crisis ensues. This is followed by a regulatory backlash leading to new, more stringent rules. The cycle then repeats.

In banking, the cycle has been characterised by recent phases of significant regulation followed by deregulation. In the UK the “Big Bang” in 1986, for example, created a revolution in London’s City, allowing banks to buy brokers and abolishing long-established fee agreements. It transformed what had been seen as a gentlemen’s club into one where all types of individuals and companies could compete in a faster-paced environment. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, a liberalised spirit prevailed not only in the financial markets but in many countries throughout the world. China established its first special economic zone in 1980. East Germany opened the Berlin Wall in 1989, followed in 1990 by German reunification. South Africa’s detested system of apartheid ended in 1990. The Soviet Union broke up in 1991. Millions of people around the world were starting to get their first taste of publicly sanctioned free-market capitalism.

But while countries seem able to make a positive transition to adapt to change, for banks deregulation often seems to be followed by going from boom to bust. It is possible to point to several instances where this has been the case. But even this cycle can offer benefits. Using the US mortgage industry as an example, deregulation encouraging institutions to keep granting mortgages in the 1970s led to excesses and the eventual failure or closure of many of these mortgage lenders. Stricter regulation ensued. In the 1990s, mortgage-backed securities offered banks a way to “securitise” mortgage loans and other asset types in order to avoid having to set aside capital to safeguard against the risks of direct lending. Thus, to circumvent capital rules, a new industry was born. Some would argue that this made mortgages available to many people who otherwise would not have been in position to finance their own home. Securitisation, for example, in mortgage instruments would within two decades be widely blamed for unleashing a crippling financial crisis. However, it also allowed new structures and ideas to be put in place. Depending upon the phase in the market cycle, stricter regulation may be greeted as either beneficial or onerous.

The crisis of 2008 added fuel to the regulatory fire, and politicians who survived the debacle have made themselves popular with many voters by vowing to curb bank excesses and cap bankers’ salaries. Banks that had to ask their governments for bailout money were not in position to protest. Governments through bailouts felt they had earned the right to intervene at both regulatory and strategic levels. The trajectory toward increasing regulatory pressure is expected to be maintained. Regulation will increase.

Threats and Enablers

Among factors driving the world towards stricter regulation is the growing belief that markets may not always be efficient when left to themselves. While efficient market theory may work in a vacuum, the human factor creates unpredictability. Humans, unlike markets, are not always rational.

Regulation is also being driven by the real threat that a large bank could go bust. Apart from the systemic risks such banks present, contributions these institutions make in good years in terms of tax revenues generated and jobs provided lend weight to the argument that a bank can be “too big to fail.” Even though some have slimmed down since the crisis, large banks may still have assets several times greater than their home country’s gross domestic product. Governments will protect the banks’ long-term viability as needed through stricter regulation to avoid, if possible, the threat of further bailouts.

Cooperation on regulatory issues can also be beneficial to banks. This is true especially when adopting rules provides “reciprocity” with the other party. In the flat tax agreements with Germany and the UK, for example, part of the agreement calls for giving Swiss banks better market access in those countries. Globalisation also is extending not just the reach of companies but the reach of governments and regulatory bodies. Technology, too, is leading to more complex products that require sophisticated oversight. With the capability to move assets and prices at speeds hard to imagine in the past, the dramatic recent events in markets have shown that selloffs can hit quickly, affecting prices from Singapore to New York. Whether “animal spirits” or simply humans acting in their own perceived self-interest are to blame, the speed at which markets can move may justify certain regulatory safeguards in this regard, too. Banks also want to reassure clients, shareholders, and the governments in their respective countries. This climate may make it easier to introduce legislation and new rules aimed at strengthening the banking system.

There are also forces driving changes apart from efforts to create a level playing field. Private banking is often accused of turning a blind eye to money laundering. Switzerland has made efforts in the past two decades to put an end to such abuses of its banking system. These include know-your-customer rules under which banks that do not report suspicious activity can be penalised. In addition, the Financial Action Task Force, an international group with representatives from 34 governments and two regional organisations and operating under the auspices of the OECD, regularly puts pressure on financial centres it regards as lax. Set up in 1989, its mission has been to develop policies to combat money laundering and terrorist financing. To achieve its aims, it rates countries based on how effective they are at combating money laundering. For further details on the bodies overseeing financial firms and an overview of some key rules, see the Appendix.

HOW REGULATORS AND THE INDUSTRY ARE ADDRESSING GLOBAL AND NATIONAL CONCERNS

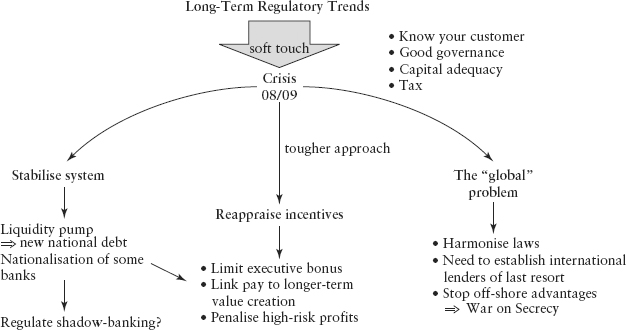

As shown in Figure 4.3, long-term regulatory trends may focus on a variety of laudable goals. These include good governance, a fair tax regime, ensuring banks are adequately capitalised, and efforts to stamp out criminal abuse. Against this backdrop, the financial crisis of 2008 had the effect of triggering another wave of regulation. The rules that followed the crisis aim primarily at stabilizing the system. They reexamine incentives blamed for excessive risk-taking. They also tackle the sheer enormity of challenges facing what is today a highly globalised industry. For each of these three areas of concern responses have been developed. While this book was being written, major changes were still in the offing, but the trends are easy to identify. They run in the direction of much stricter regulation on all fronts.

The “War on Privacy”

The pressure on Swiss banking secrecy accelerated following the 2008 US presidential election. President Barack Obama was involved in efforts to curb use of tax havens to stop tax abuse. Prior to the election, two legislators from opposing political parties (Senator Carl Levin, Democrat from Michigan and Senator Norm Coleman, Republican from Minnesota), along with the then-Senator from Illinois, Barack Obama, introduced legislation to combat offshore tax haven and tax shelter abuses under the Tax Shelter and Tax Haven Reform Act of 2005. Although the bill was not enacted, the Obama administration and other governments continue to put pressure on foreign banks to provide more transparency about their clients. And in July 2011, a new US bill called the Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act was introduced by Senator Levin.

Bank secrecy has led to heated discussions in Europe as well. German Finance Minister Peer Steinbrück provoked outcry in Switzerland in 2008 when he said at a meeting “instead of just cake, we’ve got to use a whip” to put pressure on the Swiss, saying the country should be put on a blacklist if it refused to become more cooperative on taxes.(1) The pressure increased as Germany employed what were considered illegal measures to acquire data from a Liechtenstein bank that revealed the identities of a large number of alleged German tax evaders.

Of course, there are those who say some countries’ governments have gone too far in their regulatory zeal. In September 2008, the then-President of the Swiss Banking Association, Pierre Mirabaud, complained that surveillance had become almost “Orwellian.” Swiss banking secrecy has been compromised in the eyes of many in the nation through events in the past years. In 2009, UBS agreed to release the identities and account information for about 4,450 clients believed to have violated US law, fearing that if it did not comply with the US request, it could have lost its US banking licence or faced a bigger fine. As it was, UBS paid a fine to the US government of $780 million.

Booking Centre Competition

The local regulatory frameworks governing various booking centres* can make these more or less attractive in the eyes of foreign banks and investors. Financial centres compete for business. This also is a major factor driving regulation, as the various centres demand that they be granted a level playing field. Competition also has become fiercer due to new financial hubs that have sprung up in past years. Singapore in particular has become a force not only in Asia, but globally. In only four decades it has established a thriving financial centre based on strong international trading links, efficiency, deep and liquid capital markets, and a strategic location as the gateway to Asia. In 1999, Singapore’s government decided to establish Singapore as a private banking centre. The subsequent regulatory developments have boosted the growth of the industry, making it one of the most significant emerging financial centres. Hong Kong, too, has grown in importance to wealth management and private banking. Hong Kong, a special administrative region of China, has a strong economy, excellent domestic and international services, and a long history as an international trade and financial centre.

CONCLUSION

In terms of banking, Switzerland is a financial powerhouse. With two global banks, and a number of private institutions managing client wealth, the assets overseen by these institutions both for Swiss nationals and nonresidents totaled 5.5 trillion Swiss francs at the end of 2010. The regulatory environment for Swiss private banks will be influenced by many factors. Chief among these are rules governing cross-border business and those designed to protect consumers. Changes are expected to continue and will lead to more regulation. If the trend toward a separation of investment banks and banks taking client deposits continues, this could bring about changes that provide opportunities for mergers and acquisitions.

NOTE

1. Der Spiegel Online. Steinbrück sagt Steueroasen den Kampf an. 21 Oct 2008. Accessed Nov 2011. http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/0,1518,585512,00.html.

APPENDIX: SOME KEY REGULATORY BODIES AND LEGISLATION

Rules and, therefore, costs rise with the number of markets a bank operates in. Rules governing different jurisdictions coupled with a growing body of legislation governing how a bank interacts with specific clients is further increasing costs and the time spent ensuring compliance is adequate to the task. It is the job of international regulatory bodies to turn the demands originating at the policy level into recommendations or minimum standards. Failure to implement these can be met with sanctions and the threat of exclusion. In this portion of the book, various international and national bodies are described that play a key role in regulatory oversight. There is also a description of some, but by no means all, of the pertinent legislation that is having an impact on the industry.

International Regulatory Bodies

While not exhaustive, this list provides an overview of some of the more significant regulatory organisations that have been active in the recent discussions on banking regulation.

Bank for International Settlements

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) was established in 1930 and serves today as a centre to promote cooperation among the world’s central banks. Regular meetings are held at its headquarters in Basel to discuss the global economy and markets. It publishes research reports, monitors worldwide lending, and serves as a forum for issues pertaining to international banking for both the public and private sector. It also provides the premises for the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision.

Basel Committee

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision serves as a forum for representatives from over 20 nations, having been expanded over the past decade from a small group to a larger one, reflecting the growing importance of emerging nations to the global economy and the strong growth in bank assets in these economies. It formulates standards for banking that must be first drafted into national law to be enforced, the most recent being “Basel III.” While the Committee does not have the power of enforcement, its rules offer a standard of continuity and uniformity that ideally should lead to a level playing field for banks throughout the world. The latest set of rules governing capital is set to be phased in starting January 2013 and to be completely in force by January 2019.

Financial Action Task Force (FATF)

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is an independent intergovernmental body that was established in 1989. With its administration housed in the OECD, it combats money laundering and seeks to halt financing of terrorist networks. Its 40 recommendations on money laundering and nine special recommendations on terrorist financing are aimed at curbing abuses in these areas. It also ranks countries in terms of their efforts to prevent criminal activity of this nature, bringing pressure to bear on those that fail to show progress in halting these activities.

Financial Stability Board

Previously known as the Financial Stability Forum, this body, like the Basel Committee, is based at the Bank for International Settlements. It includes both government regulators and representatives from major banks. Set up in 1999, it has a more hands-on role that includes assessing vulnerabilities that could arise in markets and the financial system. Its tasks also include monitoring markets, contingency planning, and setting up early warning systems.

International Monetary Fund (IMF)

With its 187 member countries, most countries in the world belong to the IMF. It aims to promote international monetary cooperation and exchange rate stability. It also can provide resources, including loans to members suffering payment difficulties. Among its activities in response to the financial crises, besides lending programs to emerging countries, recently it has assisted Greece by providing loans during the crisis in Europe, its largest direct access to lending (as opposed to “precautionary access” to a loan that might not be drawn down). The IMF also makes global and country economic assessments, and can offer advice on necessary reforms to ensure soundness in the financial system.

OECD

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) provides information and advice to its 34 member countries. Apart from providing offices for the FATF described here, it publishes a range of research including studies examining the reasons for the financial crisis in 2008, and ways to address the resulting economic downturn.

Partial List of National Regulators

EU

European Union (EU) regulation at the supra-national level is still rudimentary. The European Central Bank has no direct mandate to regulate or supervise banks. Much more focus to date has been on achieving a single market among the member states within the 27-nation European Union. These individual countries take decisions that affect their own markets. Germany’s Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin for short), for example, works to ensure the stability of the German financial system. It is the main supervisor for the country’s financial institutes, including 1,900 banks and 717 financial service institutions, as well as 600 insurers. In France, regulation of banks is conducted by the Banking Commission (Commission Bancaire) within the Banque de France. In Italy, the Bank of Italy, and the Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa (CONSOB) supervise the country’s banks and financial markets.

Switzerland

The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) protects investors and ensures the functioning of financial markets. It also acts as a supervisor and regulator for the financial industry and has authority over banks, insurance companies, exchanges, and securities firms and investment vehicles. FINMA is also the regulator in Switzerland responsible for adopting the global capital adequacy standards spelled out by the Basel agreements, including Basel III, into national law. The Swiss traditionally make the rules tighter, adding the so-called Swiss finish to boost capital beyond the minimum spelled out by the international guidelines.

United Kingdom

One change in the UK, in the wake of the 2008 crisis, is that one of the country’s regulators, the Financial Services Authority (FSA) that was financed by the firms that it regulates is being abolished in 2012, following what was viewed as its widespread failure to adequately oversee the markets it was supposed to be monitoring. The Bank of England, (BOE) founded in 1694 as the government’s banker, will instead absorb the FSA. Besides its role as a central bank, the BOE is responsible for protecting and enhancing the stability of the UK’s financial systems. As the FSA is being merged into the BOE, a new independent body has been created within the BOE, the Financial Policy Committee. Its task will be to identify, monitor, and take action to remove or reduce risks that could be potential threats to the financial system. The third part of the UK’s regulatory governance structure is the country’s Treasury.

United States

In the United States, the banking regulatory framework comprises several different bodies. The Federal Reserve oversees state banks and trust companies that belong to its system, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. regulates state banks that do not belong to the Federal Reserve System. The Fed also ensures that markets operate efficiently. In times of extreme turmoil it can, for example, inject liquidity through its open market desk. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency regulates US banks that have the word “National” or “N.A.” after their names, generally the largest banks. Regulators also include the National Credit Union Administration, and the Office of Thrift Supervision. In terms of market regulation, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has as its main objective to protect investors and maintain fair and efficient markets. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) is a government body that regulates futures and options markets in the United States, and like the SEC it can levy fines and sanctions. Unlike bank regulators that are regulated by outside agencies, the US futures industry is overseen by a self-regulatory (industry) body, the National Futures Association. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the federal body that oversees and operates US tax filings. In the fiscal year 2010, it collected more than $2.3 trillion in revenue for the government and processed more than 230 million tax returns.

Hong Kong Monetary Authority

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), which serves as Hong Kong’s central bank, is responsible for regulating and overseeing banks that fall within its region. The HKMA strengthened its supervisory role following the global financial crisis. It conducts reviews of both institutions and markets, and cooperates with other bodies in the region, including the Securities and Futures Commission, in conjunction with the Financial Secretary.

Monetary Authority of Singapore

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) serves as the central bank to Singapore and also has an extensive regulatory function. Singapore’s Parliament passed the Monetary Authority of Singapore Act, which created the MAS on January 1, 1971. It has the authority to regulate all elements of monetary, banking, and financial aspects of Singapore.

Regional and National Legislation

Here is a brief overview of some, but by no means all, of the significant regulatory developments that have been relevant for private banking during the past few years.

United States

QI

The Qualified Intermediary (QI) agreement governs foreign banks’ dealings in US securities and the treatment of US clients by foreign banks. Introduced January 1, 2001, it requires that foreign banks document all clients to determine whether the account holder or beneficiary is a US person as someone who would fall under the QI Agreement. US residents and US citizens as well as green card holders must then decide to opt for voluntary disclosure of information or else refrain from investing in US securities. If the bank fails to comply, it will lose its QI licence and can be prosecuted criminally. The QI process represents a simplification of the administrative processes for banks. It also preserves Swiss bank secrecy by leaving it up the client to choose either to disclose information or stop investing in US securities. Given that the QI regime is actually not a tax compliance regime, the US authorities want to amend the current model by implementing the so called FATCA regime, which will require the disclosure of all US clients regardless whether or not they are holding US securities.

FATCA

In March 2010, the United States signed into law the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA). The law aims to ensure that financial institutions outside of the United States report information on US citizens who hold accounts. The Act was actually contained within the Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment (HIRE) Act; based on comments by US official bodies, it is an important development in that country’s efforts to combat tax evasion by US taxpayers with investments in offshore accounts.

Dodd-Frank

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was passed in 2010 in the United States. Named for its two sponsors—Barney Frank (Representative, Democrat, Massachusetts) and Chris Dodd (retired, Senator, Democrat, Connecticut)—it creates new regulations pertaining to bank capital and leverage. It also makes changes in some of the agencies with oversight capability and adds some new ones.

European Union

Withholding Tax

The EU Withholding Tax is part of the European Savings Directive on the taxation of income earned on interest within the single market. Taking effect on July 1, 2005, its aim was to ensure that banks in all countries disclosed interest earnings of all EU accountholders. Switzerland and some other countries were unwilling to disclose account holders’ names, however, as this would violate bank secrecy laws. The withholding tax was agreed on as a compromise. It allows governments to receive the tax on interest income, while the bank can still preserve client confidentiality. Individual clients can either opt to waive secrecy to avoid paying the withholding tax or to maintain their anonymity and pay the tax, which now is 35 percent. The scope of the Directive is limited; it covers only individuals and interest payments.

MiFID

The EU’s Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) came into force in November 2007. It aims to integrate European financial markets and improve the organisation and functioning of investment firms, facilitating cross-border trading and increasing investor protection. It applies to the 27 EU members, as well as Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein. Firms covered by MiFID are authorised and regulated in their home country. An authorised firm can use the MiFID “passport” to provide services to customers in other EU member states. It works on the principle that politicians should focus on the main objectives of the legislation, leaving technical details to be worked out afterwards by specialists. In this case, the European Securities Committee (ESC) and the Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR) worked on the second (specialist) level. The CESR can then issue nonbinding guidelines for implementation by the member states (level 3) and finally, at level 4, the European Commission monitors implementation in national legislation. Those firms that do not conform to the guidelines can be prosecuted in the European Court of Justice.

Double-Taxation Treaties

Switzerland—OECD

Double-taxation treaties are bilateral agreements between countries dealing with the proper allocation of taxes in an international context. These agreements also include a paragraph pertaining to the exchange of information in tax matters. The OECD provides a double-taxation model agreement, which recommends a structure and the contents of such agreements between OECD member countries. In March 2009, Switzerland agreed to adopt the OECD standard on providing administrative assistance with regard to tax matters, including the exchange of information clause (Article 26) in the OECD’s agreement. This allows for exchanging information on tax matters in cases where a “specific and justified request” has been made. Following the agreement, the Swiss Federal Council directed the Swiss Federal Department of Finance to begin negotiations on revised double-taxation agreements with various countries, including the United States.

Switzerland—United States

In 2009, following Switzerland’s show of willingness to adopt the OECD’s standard on tax assistance, the Swiss government officially declared that it would cooperate with the United States in offering assistance not only in cases of suspected tax fraud, which were considered more serious, but in tax evasion cases, which in the past were considered a less grave offence. At the same time, Swiss banks have adamantly resisted attempts to allow so-called fishing expeditions by which foreign authorities demand a great deal of client information, hoping to catch a few tax cheats.

New Bilateral Tax Agreements with the United Kingdom, Austria, and Germany

The treaties with the UK, Austria, and Germany on the introduction of a final withholding tax were signed in autumn 2011 and spring 2012. The agreements are expected to enter into force by January 2013, providing legislators in Switzerland, Germany, the UK, and Austria approve them. Similar treaties with other countries may follow. In a nutshell, the treaties stipulate that individuals domiciled in these EU member state countries may “regularise” their existing Swiss bank accounts and deposits either by choosing an anonymous one-off flat rate payment or by voluntarily notifying the respective UK, Austrian, or German tax authorities.

Going forward, income from assets (i.e., interest income, dividends, capital gains, and other income) held in accounts and deposits with Swiss banks received by clients who live in Germany or the UK will be taxed anonymously by withholding the payments at source. Or these clients, if they choose, may instead authorise their bank to disclose their income to the relevant tax authorities and pay taxes through the normal channels.

*A booking centre refers to the place where the assets of a client are booked. The location of the booking centre is then the governing law for assets booked in this location. Assets booked in Switzerland, for example, fall under Swiss law, those in Singapore under the laws of that jurisdiction, and so forth.